|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7177c) (tudalen clawr)

|

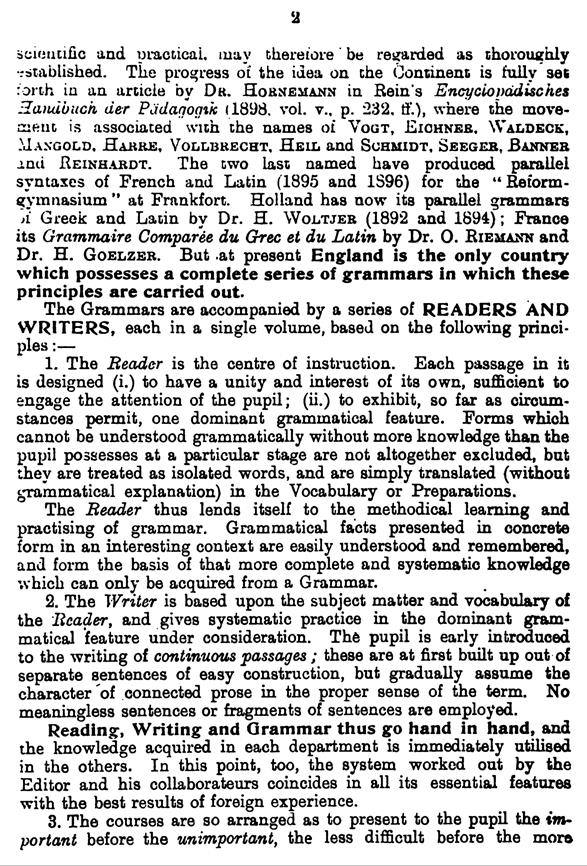

Parallel

Grammar Series

WELSH GRAMMAR

Accidence

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7178) (tudalen a001)

|

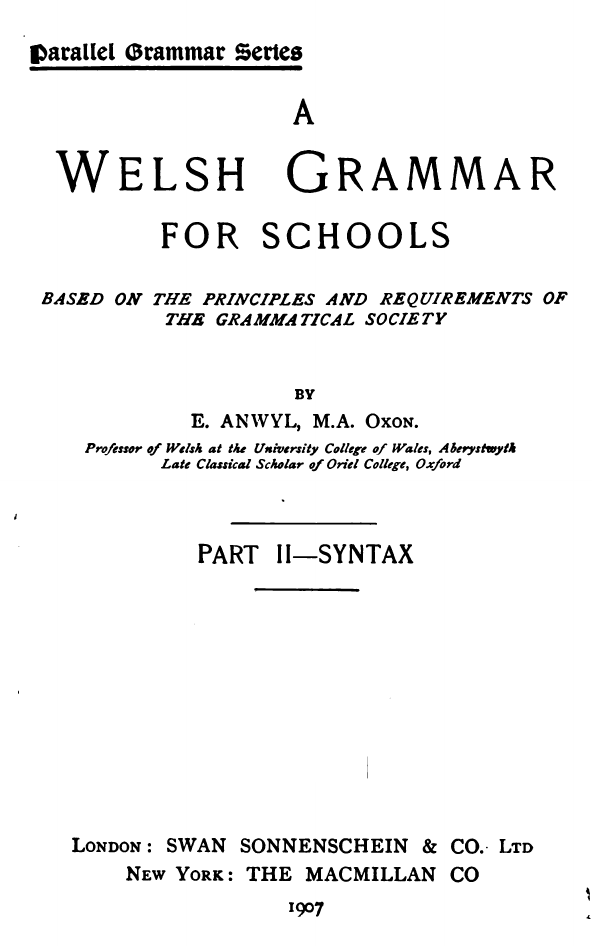

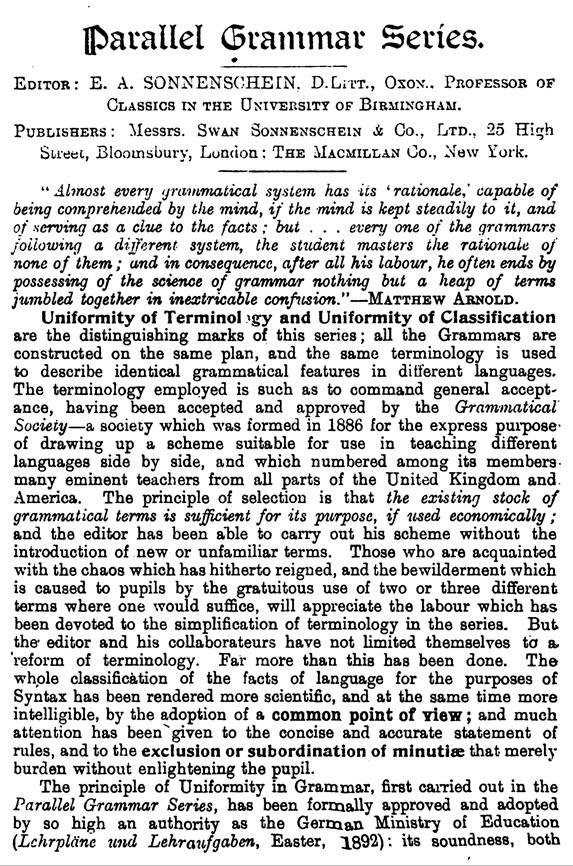

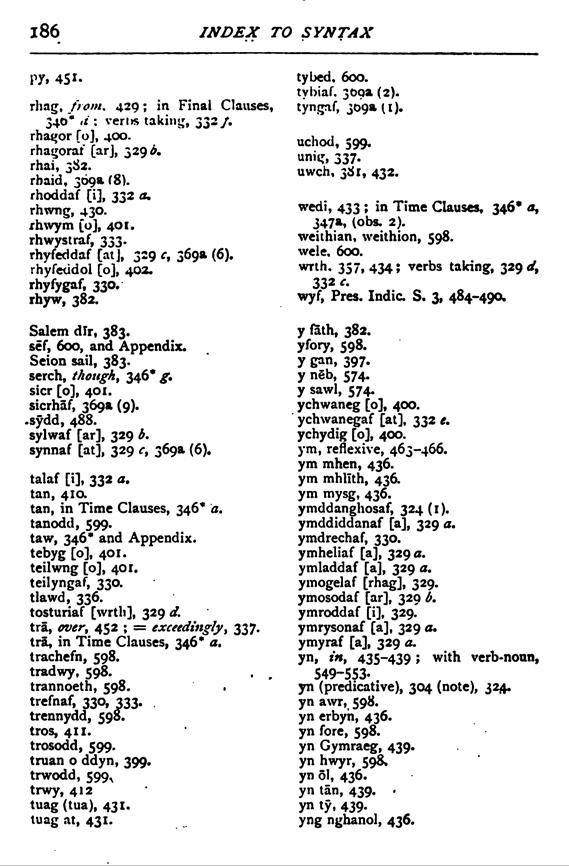

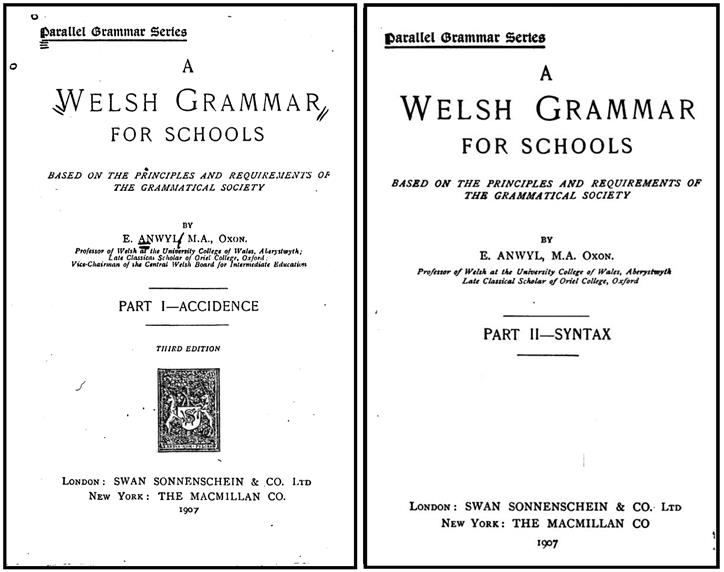

1 Parallel Grammar Series

A Welsh Grammar for Schools A Welsh Grammar

for Schools

Based on the Principles and Requirements of the Grammatical Society

by E. Anwyl, M.A., Oxon

Professor of Welsh at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth

Late Classics Scholar of Oriel College, Oxford

Vice-Chairman of the Central Welsh Board for Intermediate Education

Part 1 - Accidence

Third Edition

London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd

New York: The Macmillan Co.

1907

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7179) (tudalen a002)

|

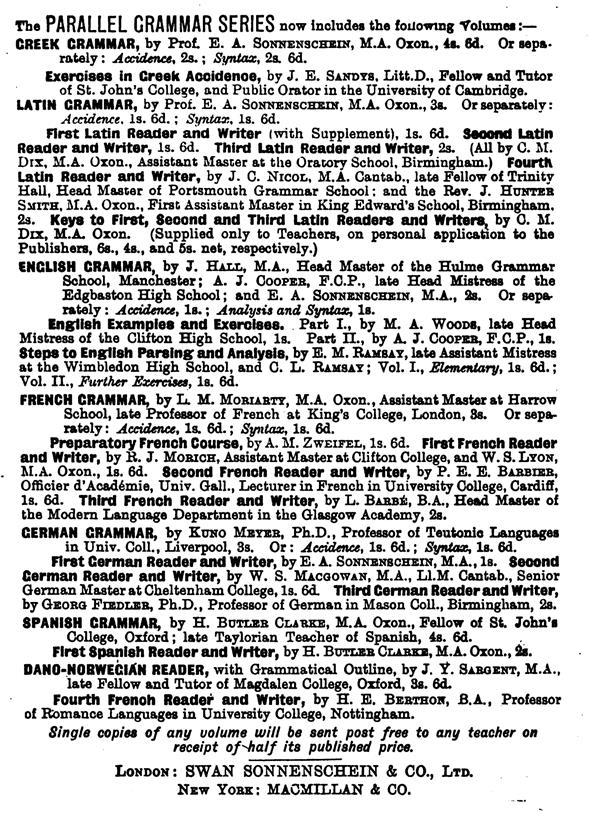

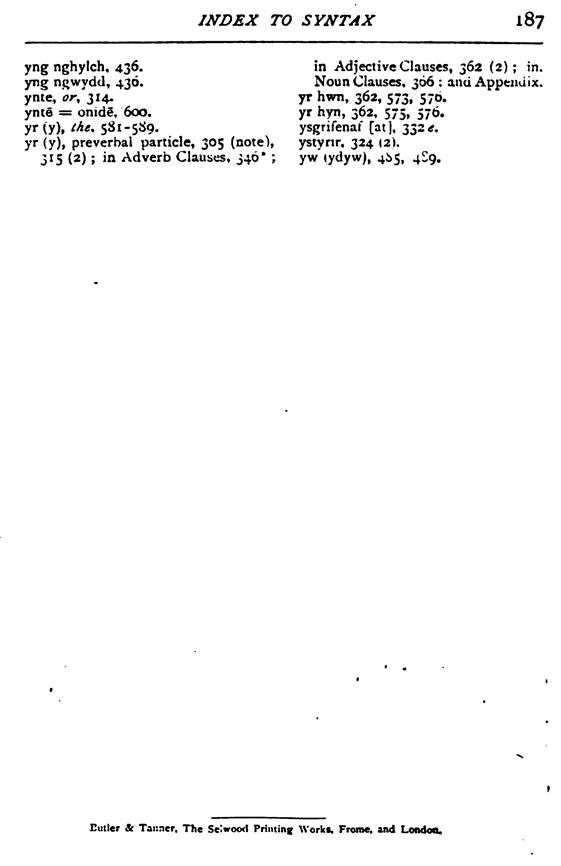

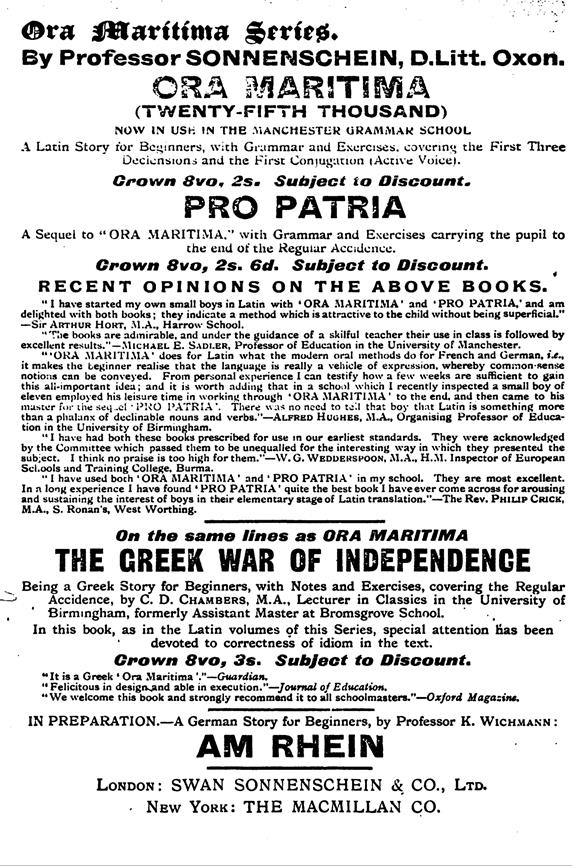

a2The

PARALLEL GRAMMAR SERIES now includes the following Volumes:— GREEK GRAMMAR,

hy Prol E. A. Sonkenschein, M.A. Oxon., 4a. 6d. Or separately: Accidenee,

2s.; Syntax 2s. 6d.

Exercises in Greek Accidence, by J. E. Sandys, Litt.D., Fellow and Tutor of

St. John's College, and Public Orator in the University of Cambridge. LATIN

GRAMMAR, by Prof. E. A. Sonnenschein, M.A. Oxon., 3s. Or separately:

Accidence, Is. 6d.; Syntax Is. 6d.

First Latin Reader and Writer (with Supplement), Is. 6d. Second Latin Reader

and Writer, is. 6d. Third Latin Reader and Writer, 2s. (All by C. I. Dix,

M.A. Oxon., Assistant Master at the Oratory School, Birmingham.) Fourth Latin

Reader and Writer, by J. C. Nicol, M.A. Cantab., late Fellow of Trinity Hall,

Head Master of Portsmouth Grammar School: and the Rev. J. Huntbb Smith, M.A.

Oxon., First Assistant Master in King Edward's School, Birmingham, 2s. Keys

to First, Second and Third Latin Readers and Writers by 0. M. Ddc, M.A. Oxon.

(Supplied only to Teachers, on personal application to the Publishers, 68.,

4s., and 5s. net, respectively.)

ENGLISH GRAMMAR, by J. Hall, M.A., Head Master of the Hulme Grammar School,

Manchester; A. J. Coopeb, F.G.P., late Head Mistress of the Edgbaston High

School; and E. A. Sonnenbchein, M.A., 28. Or separately: Accidence, Is.;

Analysts and Syntax, Is. Ensrlish Examples and Exercises. Part I., by M. A.

Woods, late Head

Mistress of the Clifton High School, Is. Part n., by A. J. Coopeb, F.C.P.,

Is.

Steps to Engrllsh Parslnsr and Analysis, by E. M. Bamsay, late Assistant

Mistress

at the Wimbledon High School, and C. L. Bamsay; Vol. I., Elementary, Is. 6d.;

Vol. II., Further Exereisea, Is. 6d.

FRENCH GRAMMAR, by L. M. Moriabty, M.A. Oxon., Assistant Master at Harrow

School, late Professor of French at King's College, London, 3s. Or

separately: Accidence, Is. 6d.; Syntax, Is. 6d. Preparatory French Course, by

A. M. Zweifel, is. 6d. First French Reader and Writer, by K. J. Mobich, Assistant

Master at Clifton College, and W. S. Lyon, M.A. Oxon., Is. 6d. Second French

Reader and Writer, by P. E. E. Babbibb, Officier d'Acadmie, Univ. Gall.,

Lecturer in French in University College, Cardiff, Is. 6d. Third French

Reader and Writer, by L. BABBi:, B.A., Head Master of the Modem Language

Department in the Glasgow Academy, 28.

GERMAN GRAMMAR, by Kuno Meyer, Ph.D., Professor of Teutonic Languages in

Univ. Coll., Liverpool, 3s. Or: Accidence, Is. 6d.; Syntax, Is. 6d. First

German Reader and Writer, by E. A. Sonnenschein, M.A., Is. Second German

Reader and Writer, by W. S. Macgowan, M.A., L1.M. Cantab., Senior German

Master at Cheltenham College, Is. 6d. Third German Reader and Writer, by

Geobq Fdbdlbb, Ph.D., Professor of German in Mason Coll., Birmingham, 28.

SPANISH GRAMMAR, by H. Butleb Clabee, M.A. Oxon., Fellow of St. John's

College, Oxford; late Taylorian Teacher of Spanish, 4s. 6d. First Spanish

Reader and Writer, by H. Butleb Clabkb, M.A. Oxon., &.

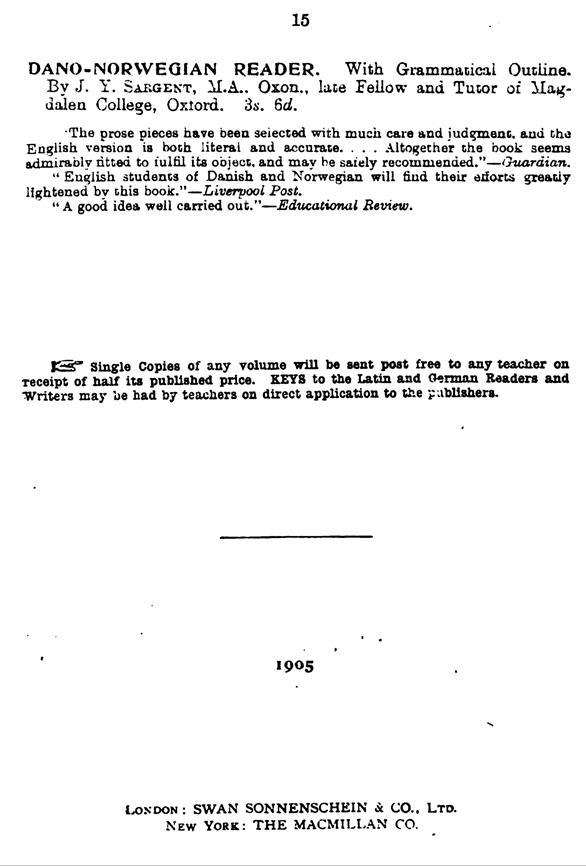

DANO-NORWEGIAN READER, with Granmiatical OutUne, by J. t. Sargent, M.A., late

Fellow and Tutor of Magdalen College, Oxford, Ss. 6d. Fourth French Reader

and Writer, by H. E. Bebthon, B.A., Professor of Bomance Languages in

University College, Nottingham.

Single copies of any volume will be sent post free to any teacher on

receipt ofalf its published price,

London: SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., Lm New Yobk: MACMILLAN & CO.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7180) (tudalen a003)

|

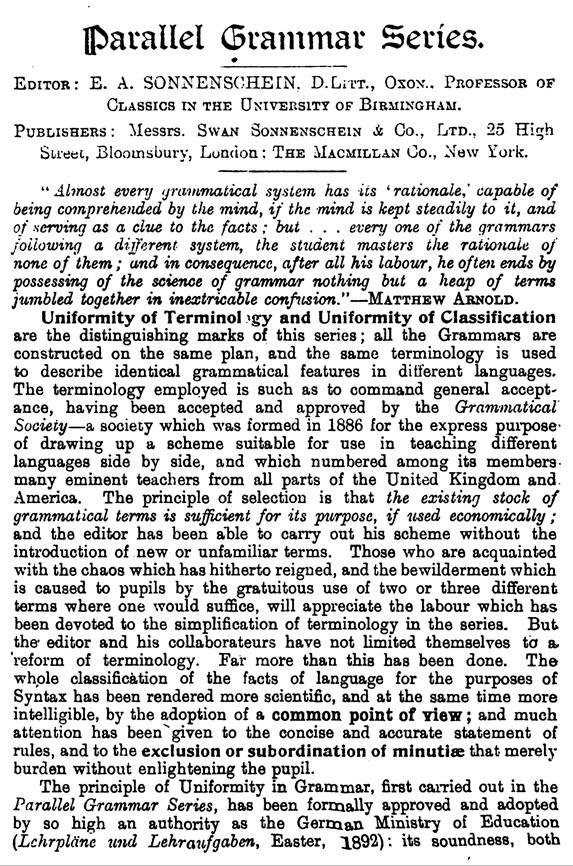

Parallel

Grammar Series

Edited

by E. A. Sonnenschein, M.A. Oxon.

Professor of Classics and Dean of the Faculty of Arts in the University of Birmingham.

WELSH

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7181) (tudalen a004)

|

First Edition, November. 1897;

Second Edition, February, 1898;

Third Edition, March 1901;

Fourth Edition, August, 1907.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7182) (tudalen a005)

|

5

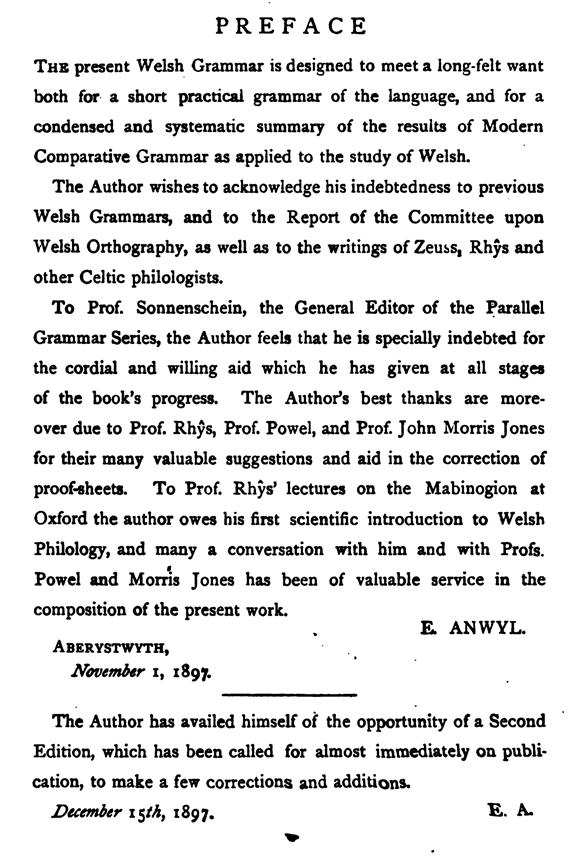

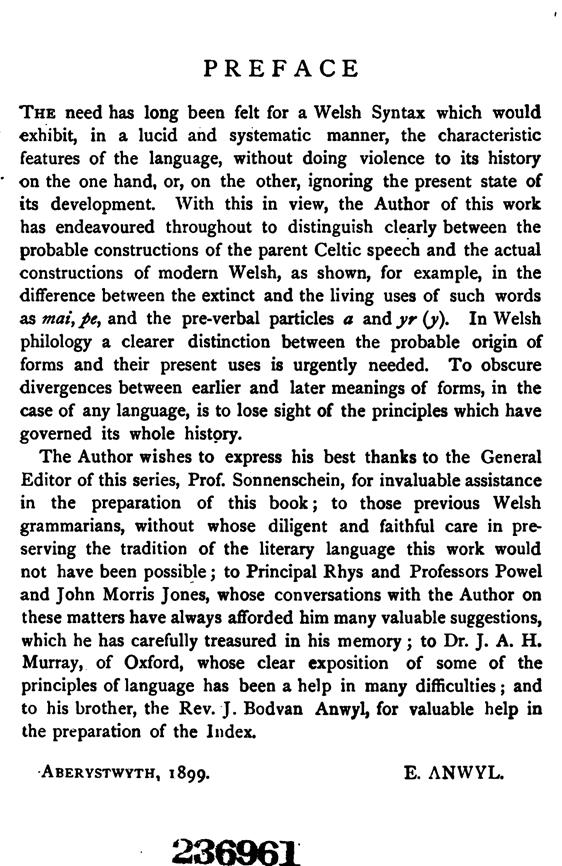

PREFACE

The present Welsh Grammar is designed to meet a long-felt want both for a

short practical grammar of the language, and for a condensed and systematic

summary of the results of Modern Comparative Grammar as applied to the study

of Welsh.

The Author wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness to previous Welsh Grammars,

and to the Report of the Committee upon Welsh Orthography, as well as the

writings of Zeuss, Rhŷs and other Celtic philologists.

To Prof. Sonnenschein, the General Editor of the Parallel Grammar Series, the

Author feels that he is specially indebted for the cordial and willing aid

which he has given at all stages of the book’s progress. The Author’s best

thanks are moreover due to Prof. Rhŷs, Prof. Powel, and Prof. John

Morris Jones for their many valuable suggestions and aid in the correction of

proof sheets. To Prof. Rhŷs’ lectures on the Mabinogion at Oxford the author owes his first scientific

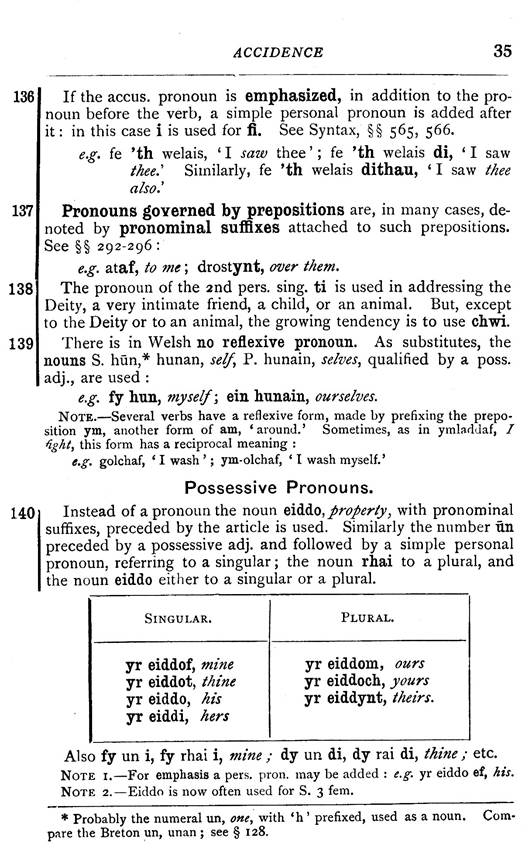

introduction to Welsh Philology, and many a conversation with him and with

Profs. Powel and Morris Jones has been of valuable service in the composition

of the present work.

E. ANWYL

ABERYSTWYTH

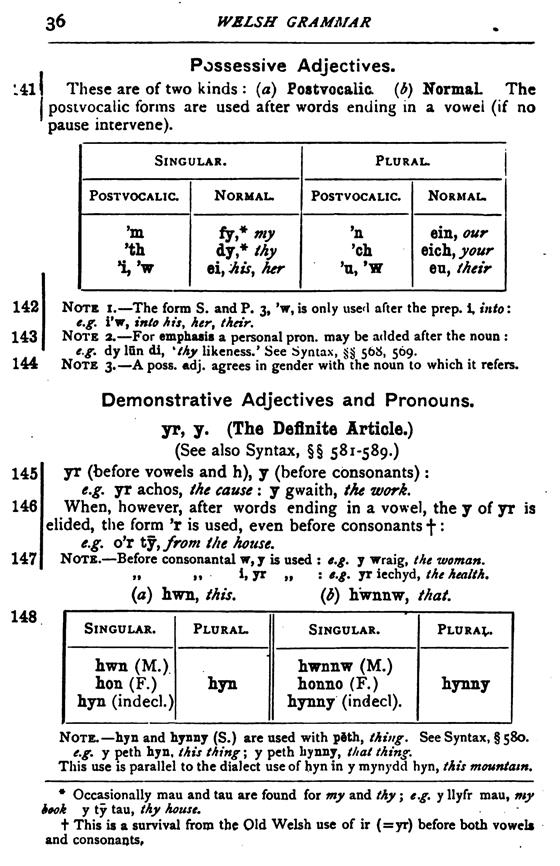

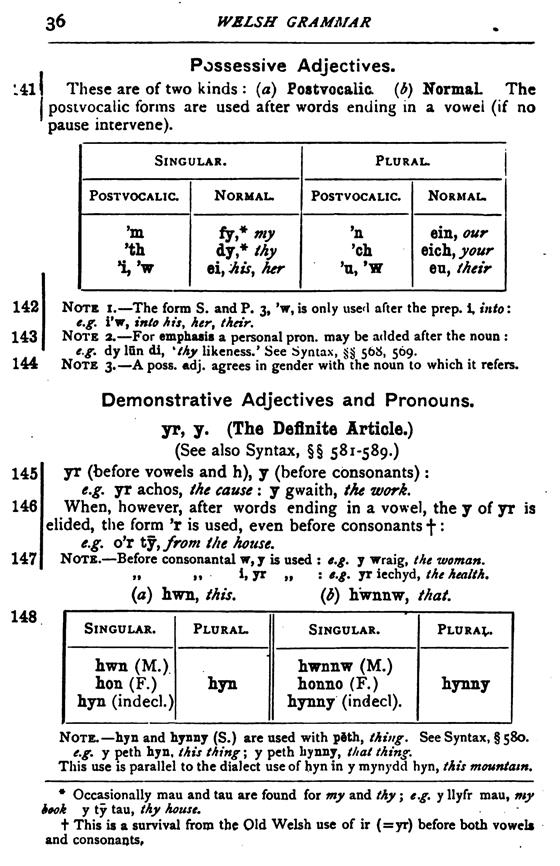

November 1, 1897

The Author has availed himself of the opportunity of a Second Edition, which

has been called for almost immediately on publication, to make a few

corrections and additions.

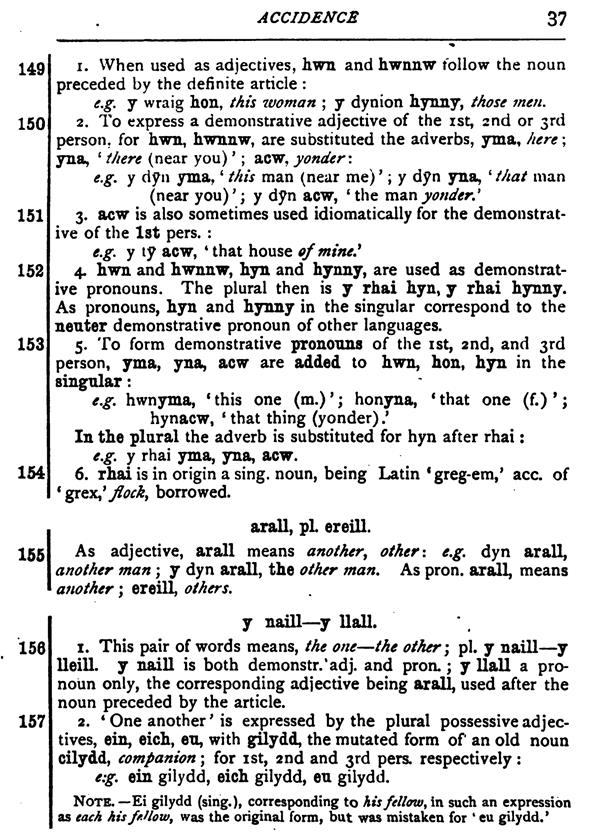

December 15th, 1897. E.A.

|

|

|

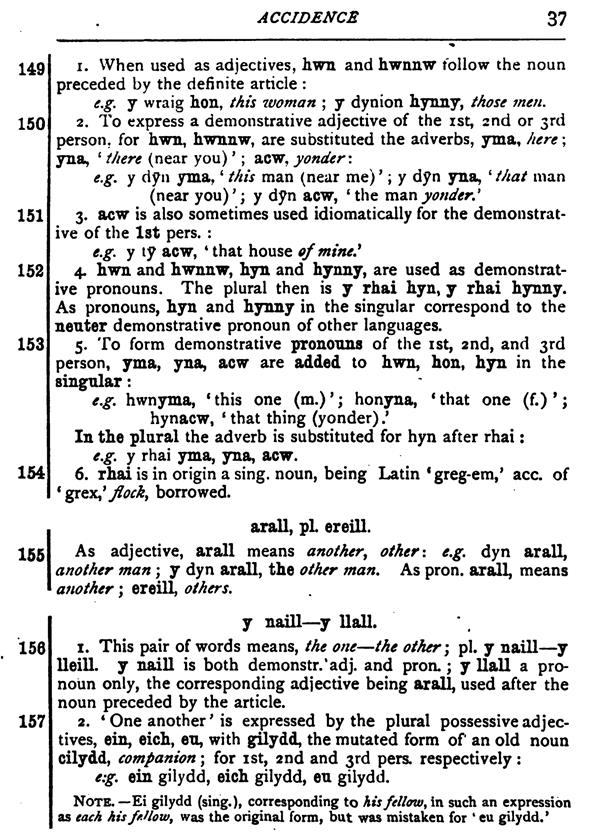

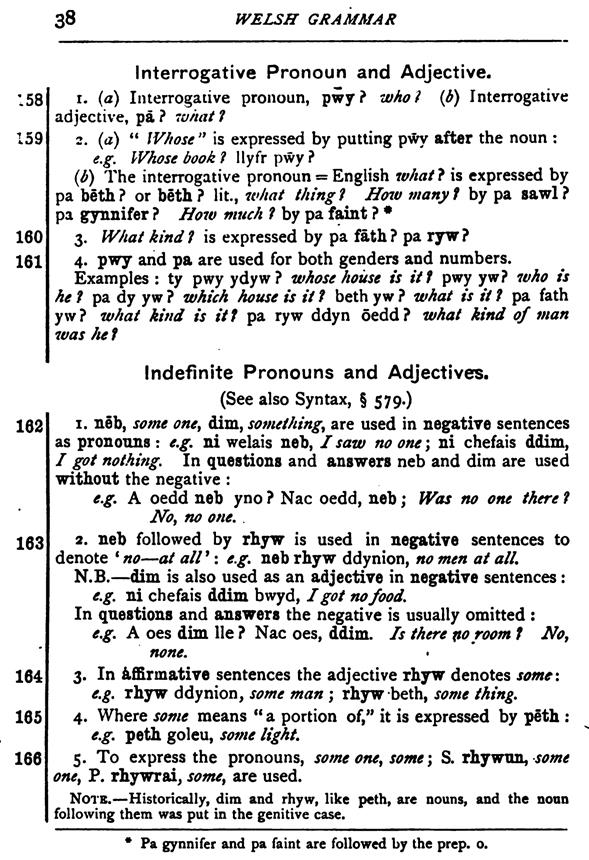

|

|

(delwedd F7183) (tudalen a006)

|

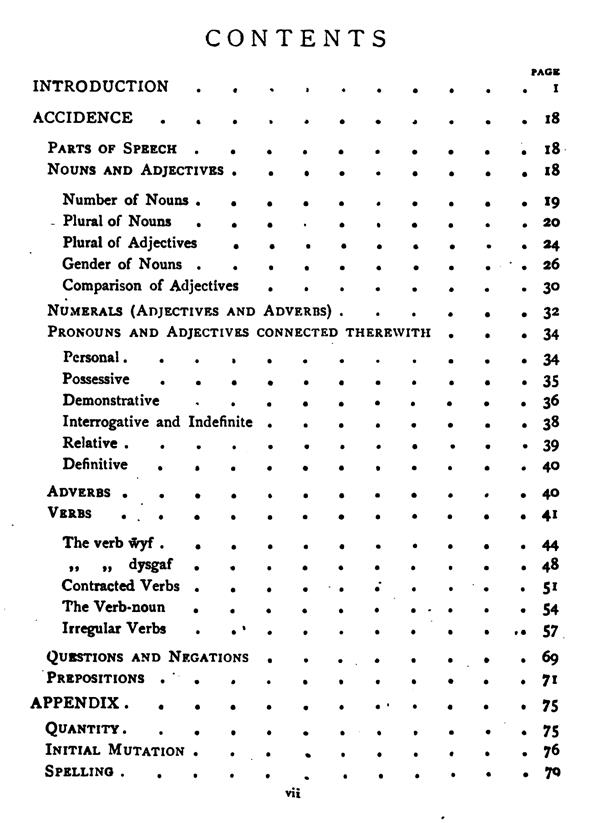

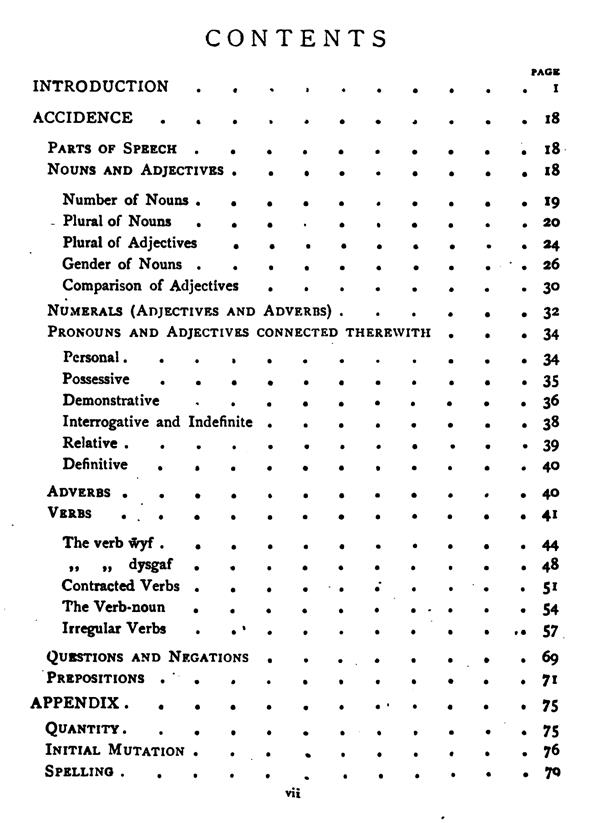

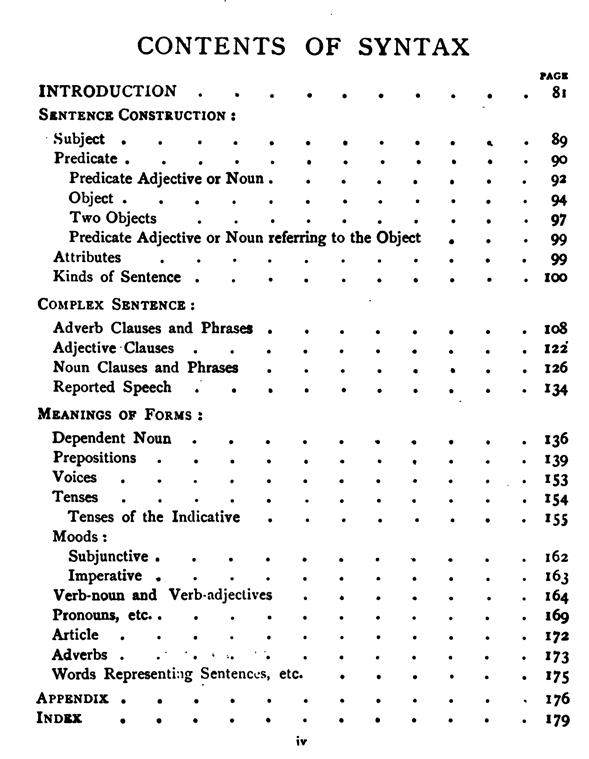

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION - Page 1

ACCIDENCE - Page 18

·····PARTS OF SPEECH - Page 18

·····NOUNS AND ADJECTIVES - Page 18

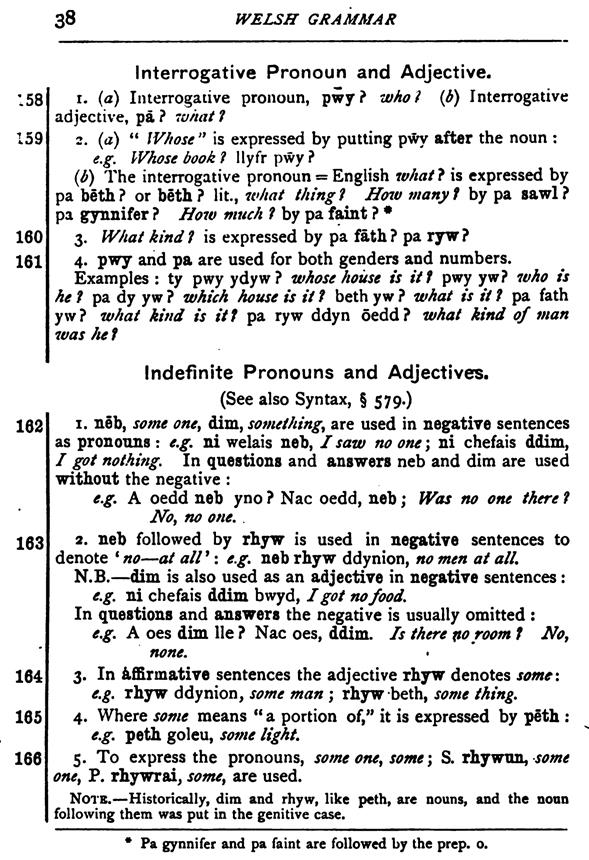

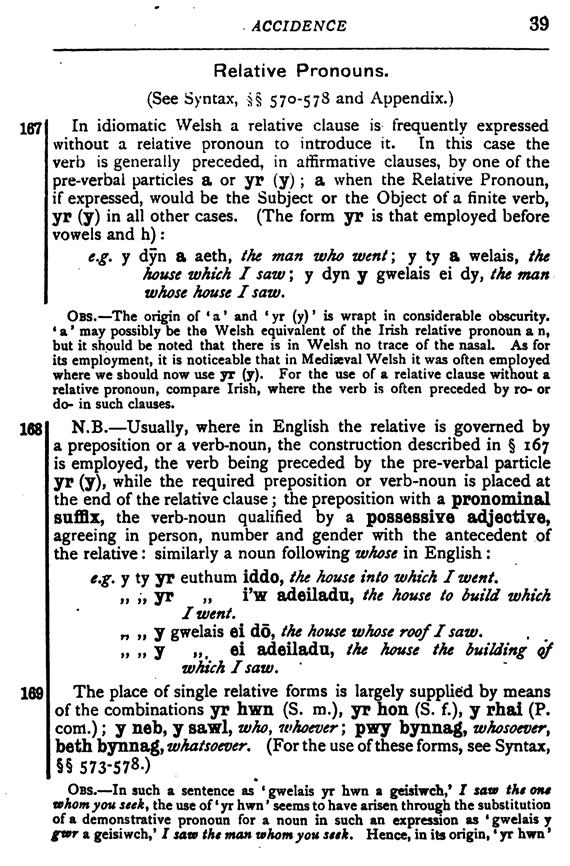

···············Number of Nouns - Page 19

···············Plural of Nouns - Page 20

···············Plural of Adjectives - Page 24

···············Gender of Nouns - Page 26

···············Comparison of Adjectives - Page 30

·····NUMERALS (ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS) - Page 32

·····PRONOUNS AND ADJECTIVES CONNECTED THEREWITH - Page 34

···············Personal - Page 34

···············Possessive - Page 35

···············Demonstrative - Page 36

···············Interrogative and Indefinite - Page 38

···············Relative - Page 39

···············Definitive - Page 40

·····ADVERBS - Page 40

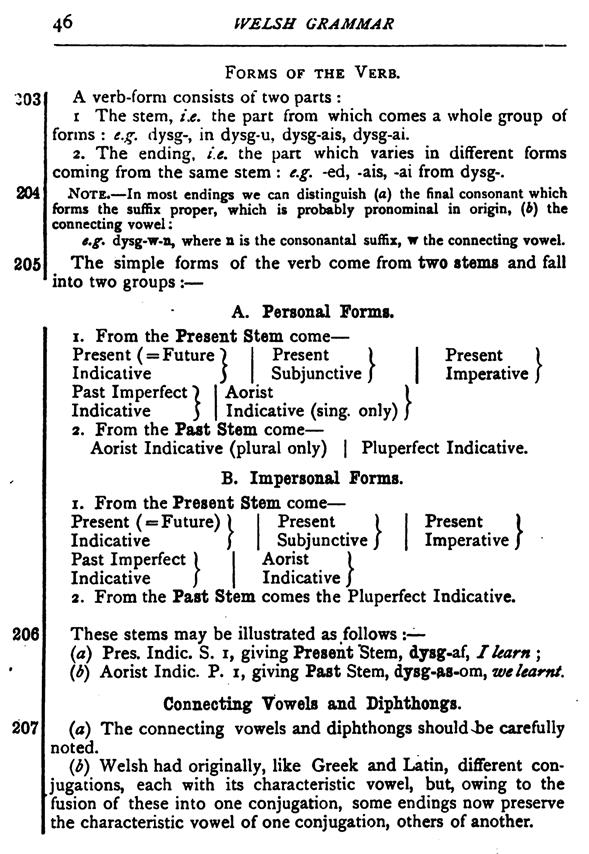

·····VERBS - Page 41

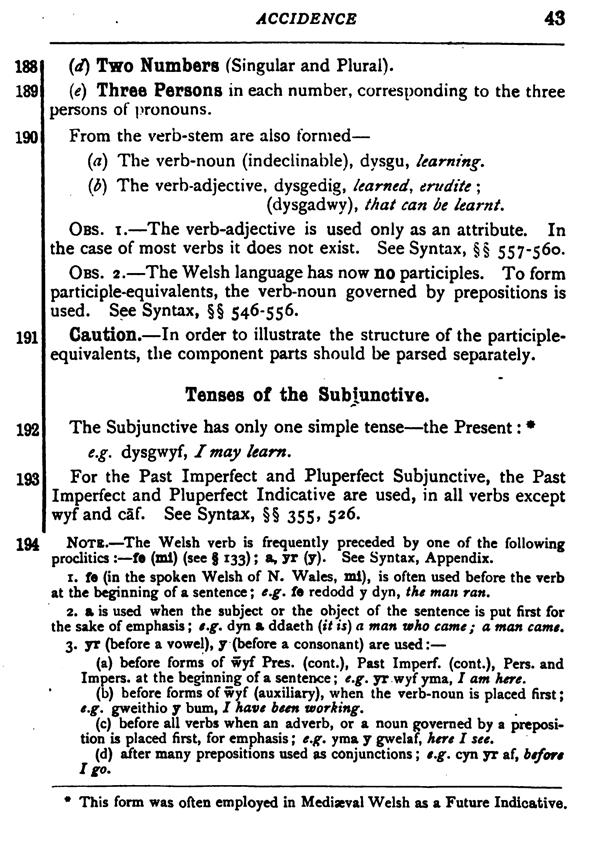

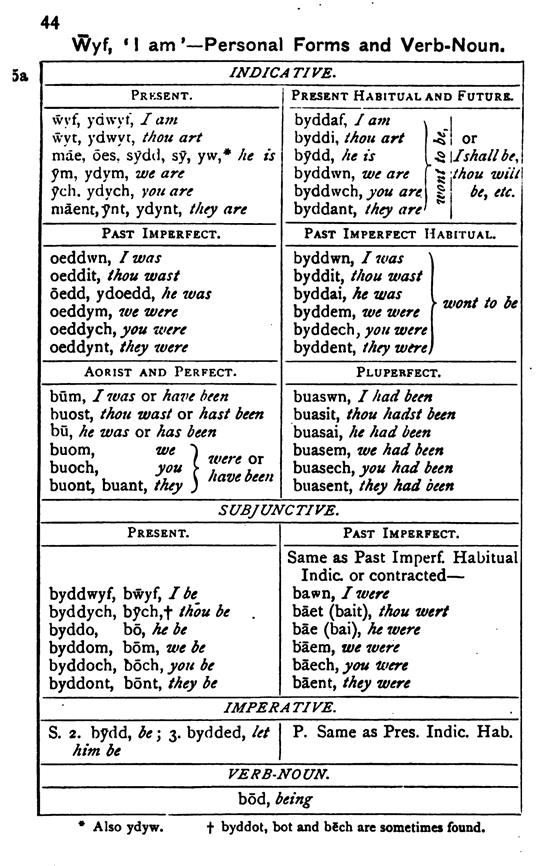

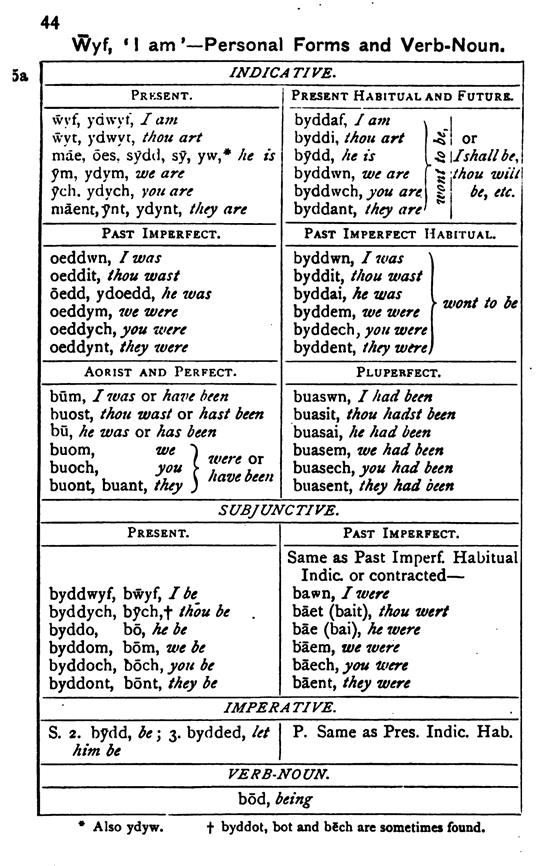

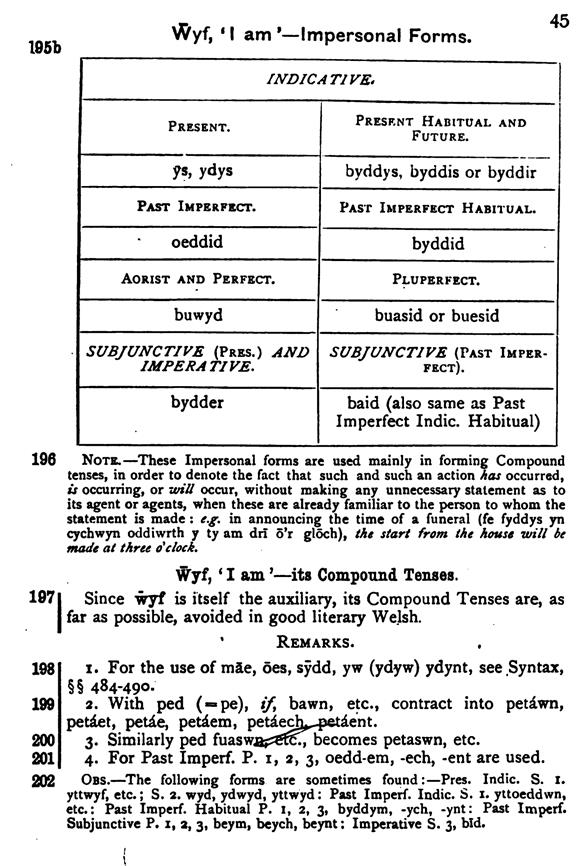

···············The verb ŵyf - Page 44

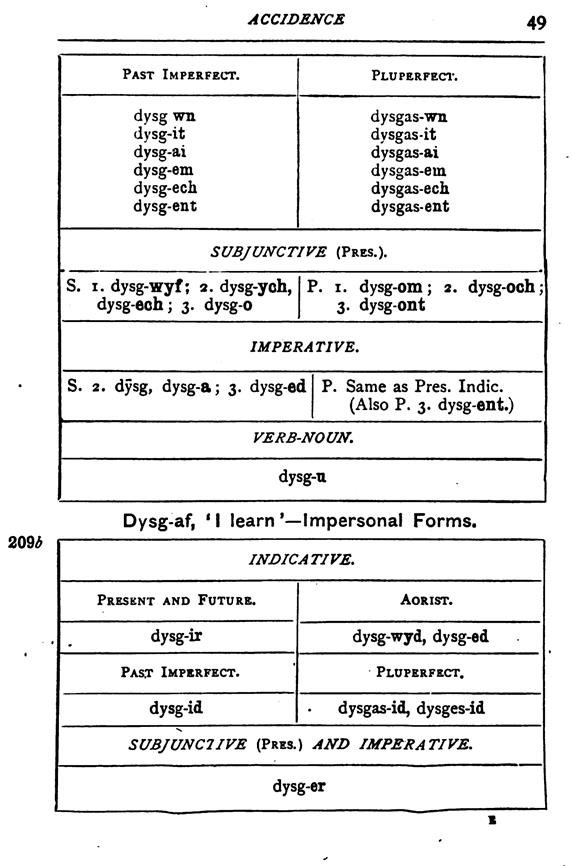

···············The verb dysgaf - Page 48

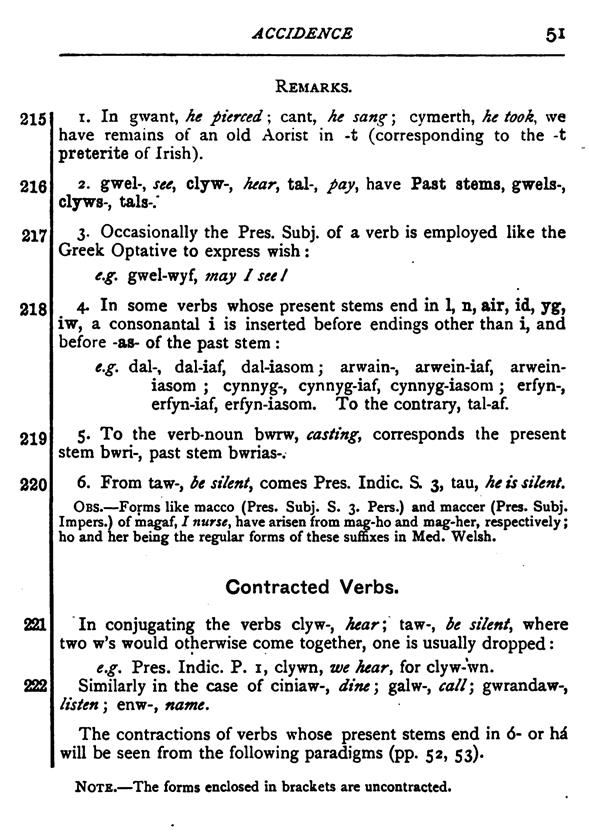

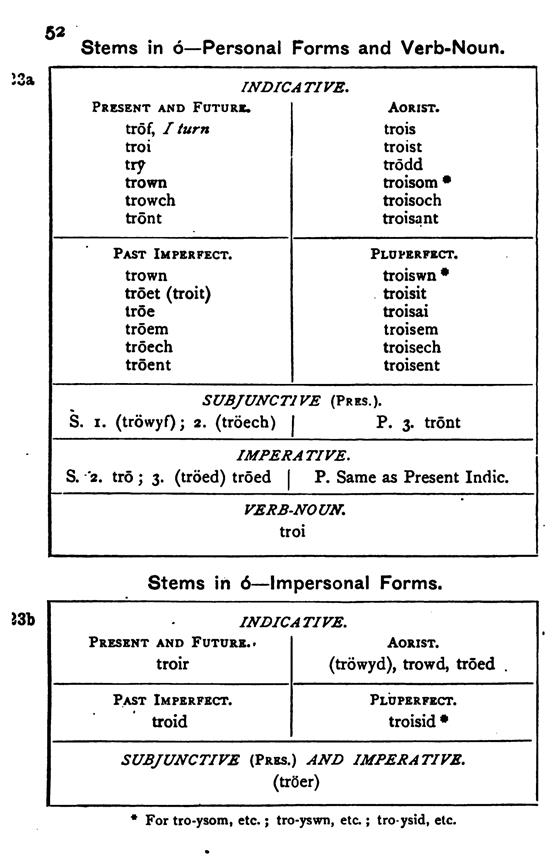

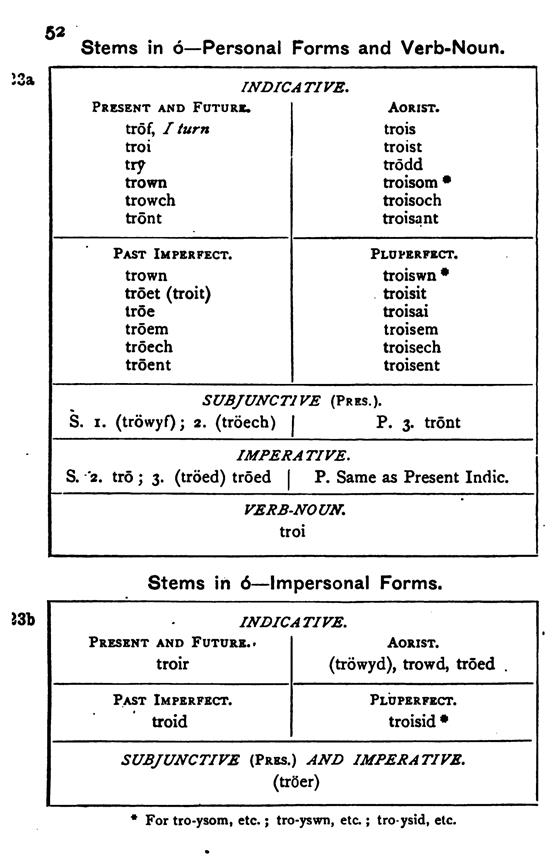

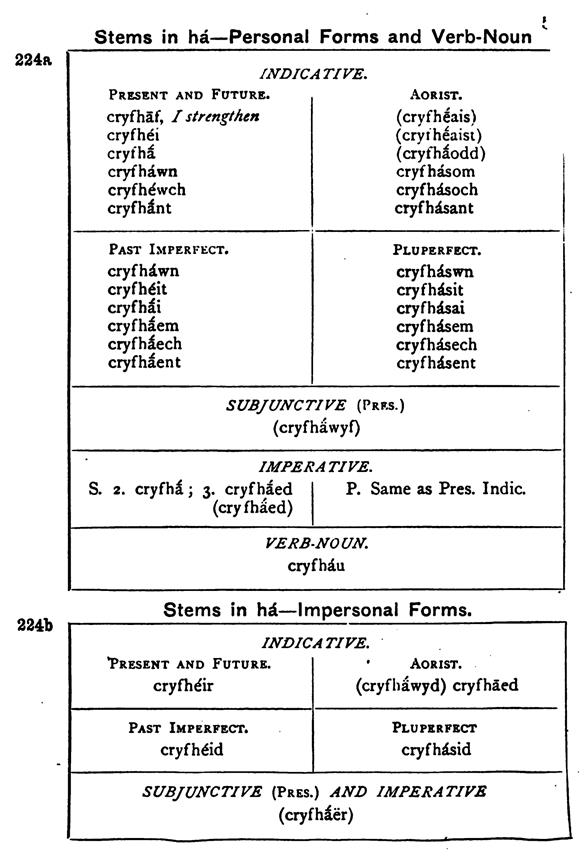

···············Contracted verbs - Page 51

···············The Verb-noun - Page 54

···············Irregular Verbs - Page 57

·····QUESTIONS AND NEGATIONS - Page 69

·····PREPOSITIONS - Page 71

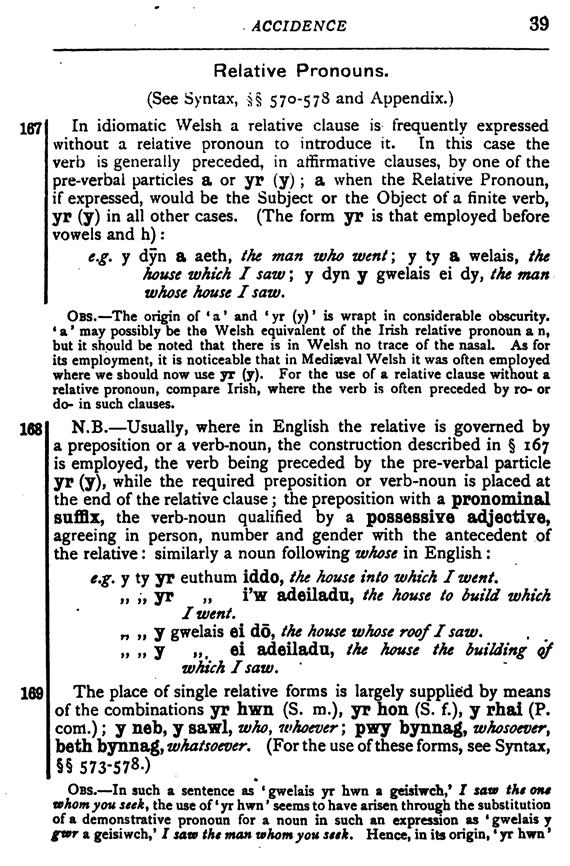

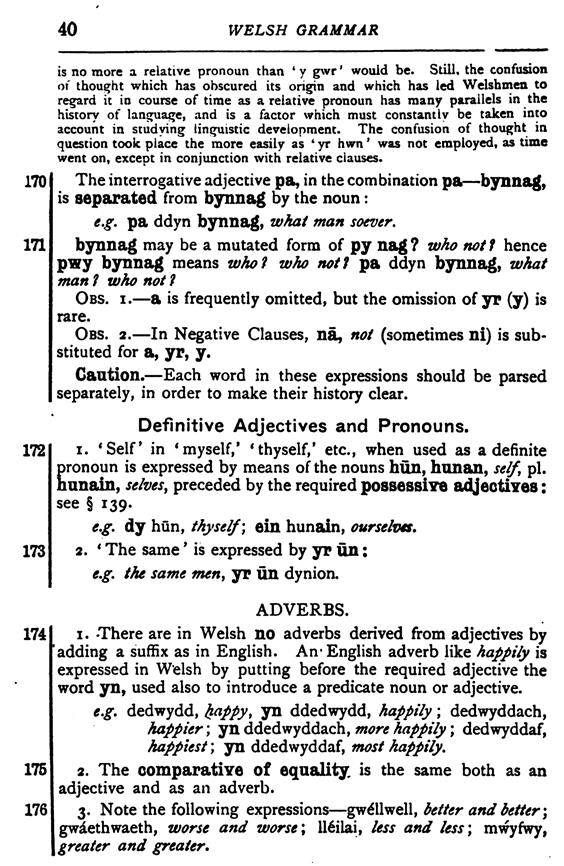

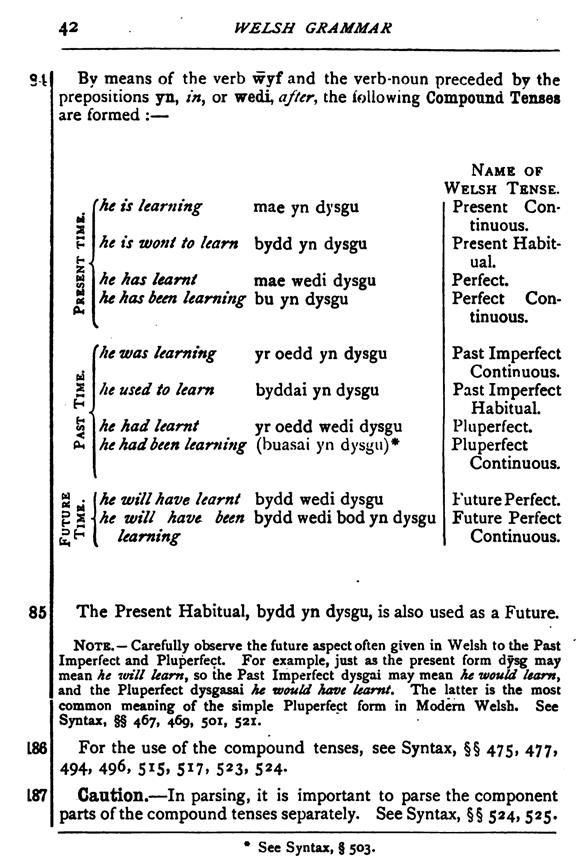

APPENDIX - Page 75

·····QUANTITY - Page 75

·····INITIAL MUTATION - Page 76

·····SPELLING - Page 79

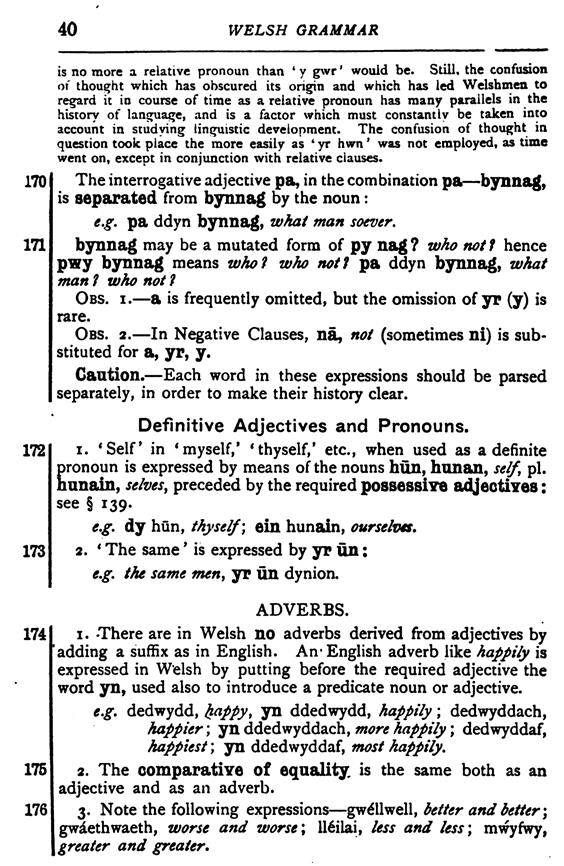

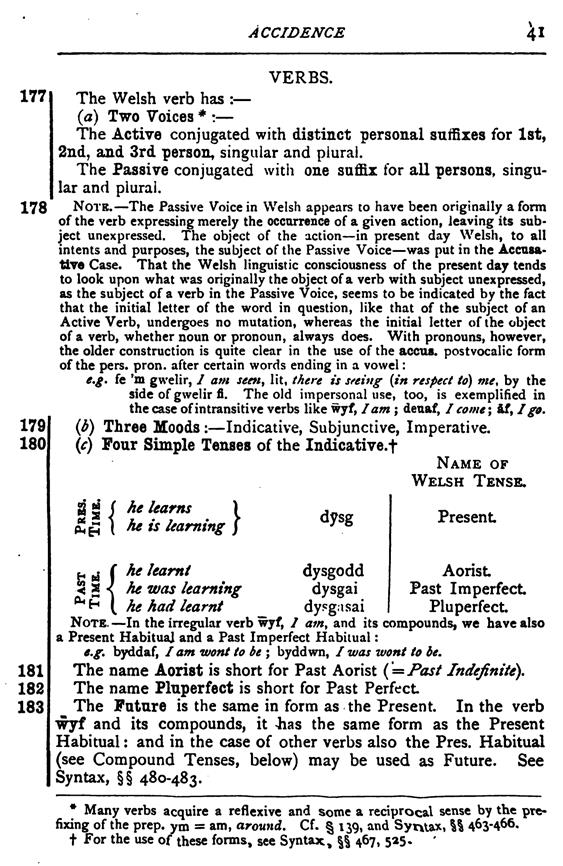

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7184) (tudalen 001)

|

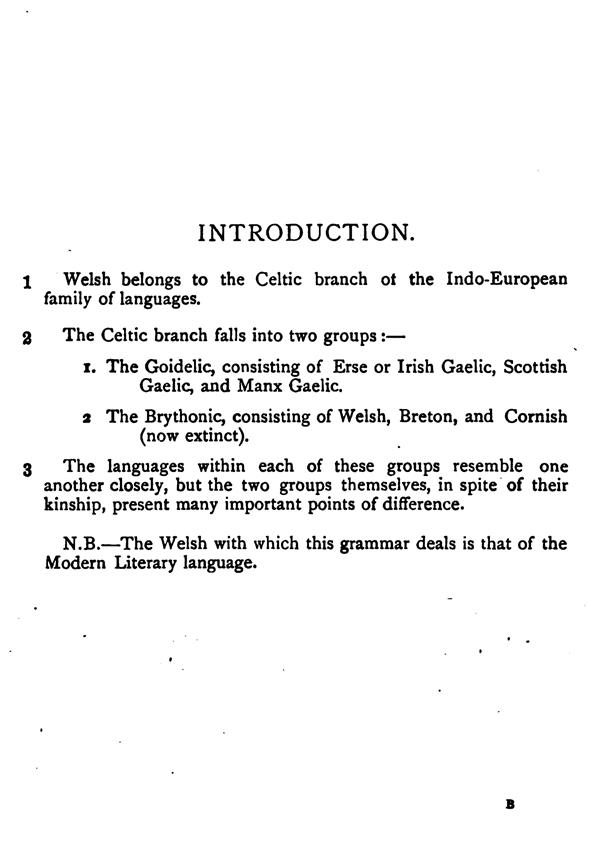

INTRODUCTION

1 Welsh belongs to the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family of

languages.

2 The Celtic branch falls into two groups: -

··········1 the Goidelic, consisting of Erse or Irish Gaelic, Scotish Gaelic,

and Manx Gaelic.

··········2 The Brythonic, consisitng of Welsh, Breton, and Cornish (now

extinct).

3 The languages within each of these groups resemble one another closely, but

the two groups themselves, in spite of thier kinship, present many important

points of difference.

N.B. - The Welsh with which this grammar deals is that of the Modern Literary

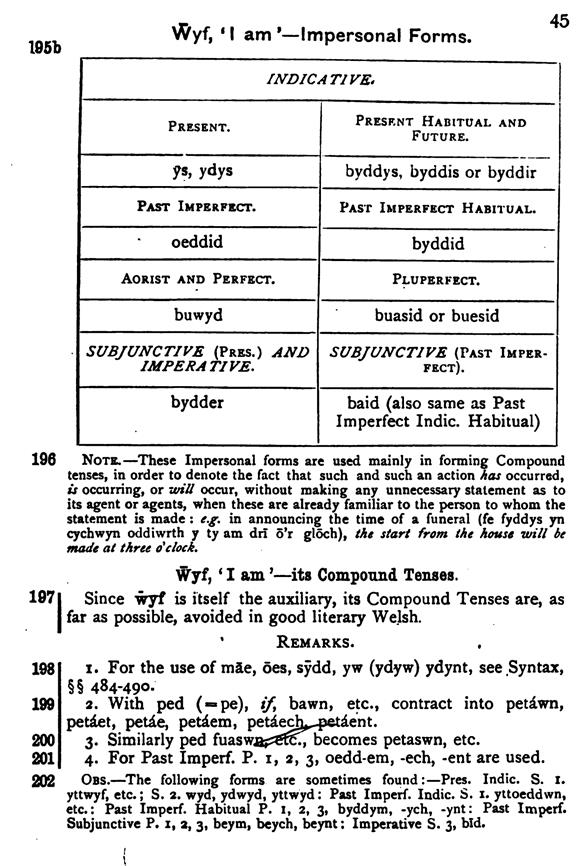

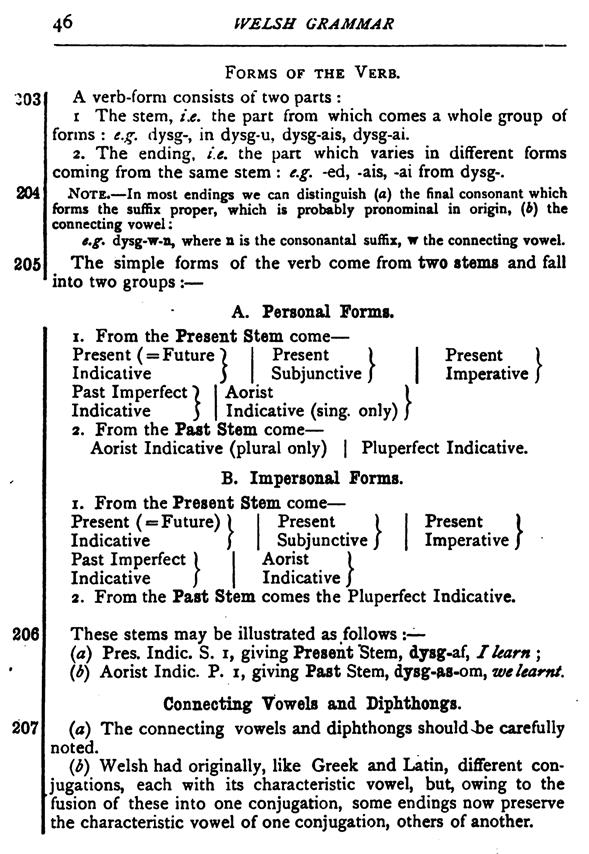

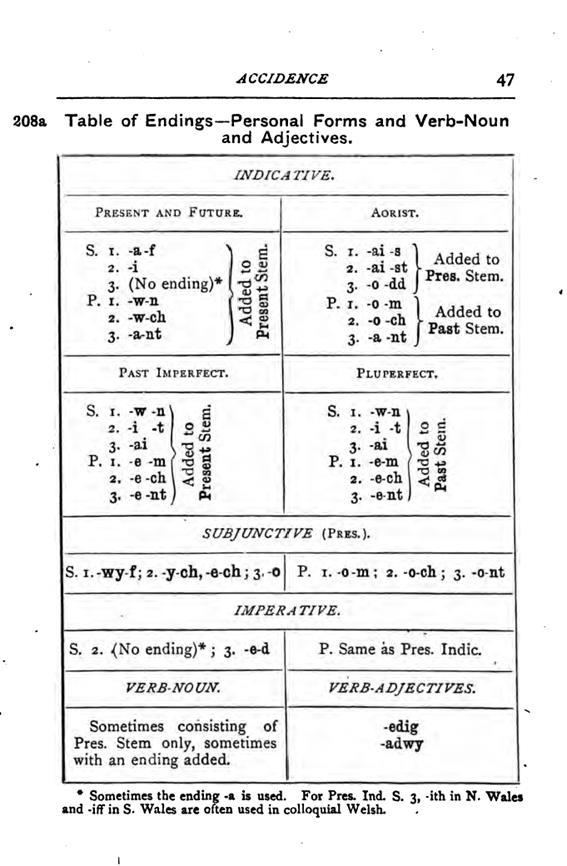

language.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7185) (tudalen 002)

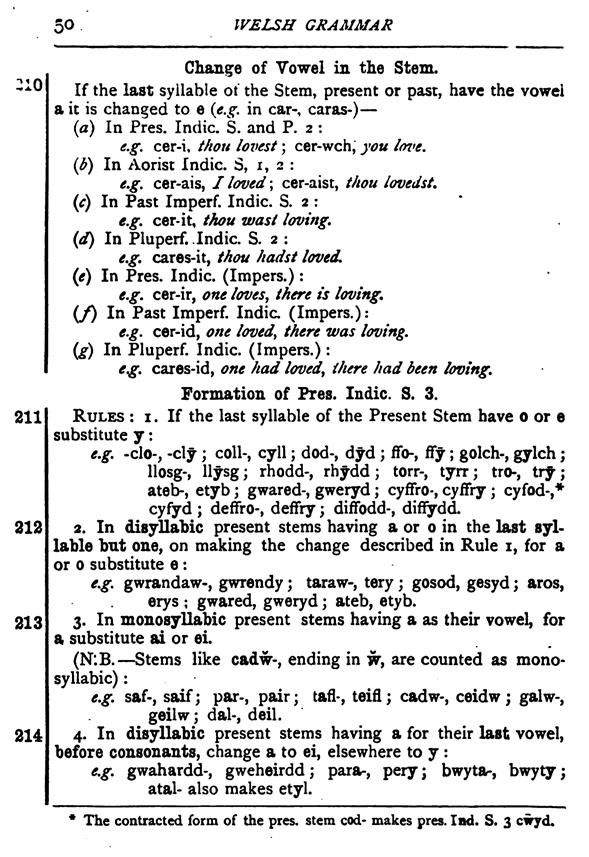

|

2 WELSH GRAMMAR

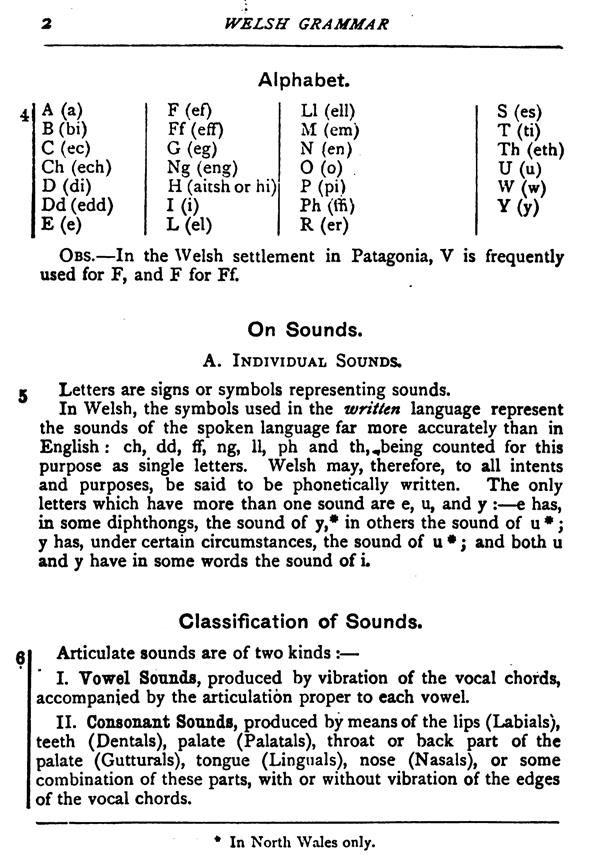

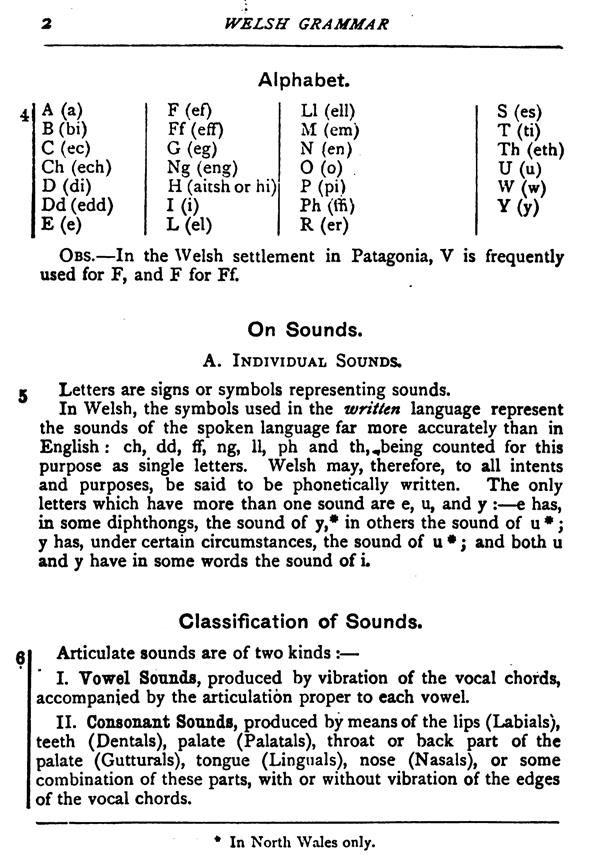

4 Alphabet

A (a)

B (bi)

C (ec)

Ch (ech)

D (di)

Dd (edd)

E (e)

F (ef)

Ff (eff)

G (eg)

Ng (eng)

H (aitsh or hi)

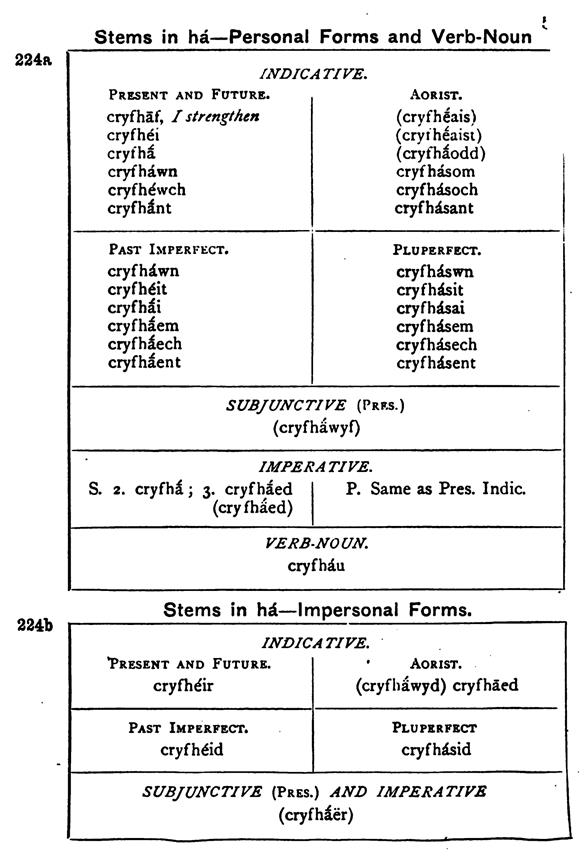

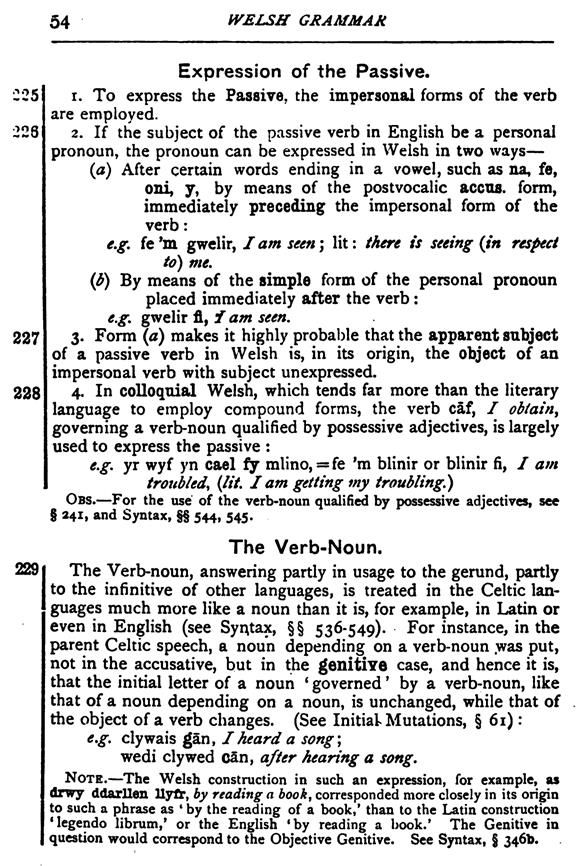

I (i)

L (el)

Ll (ell)

M (em)

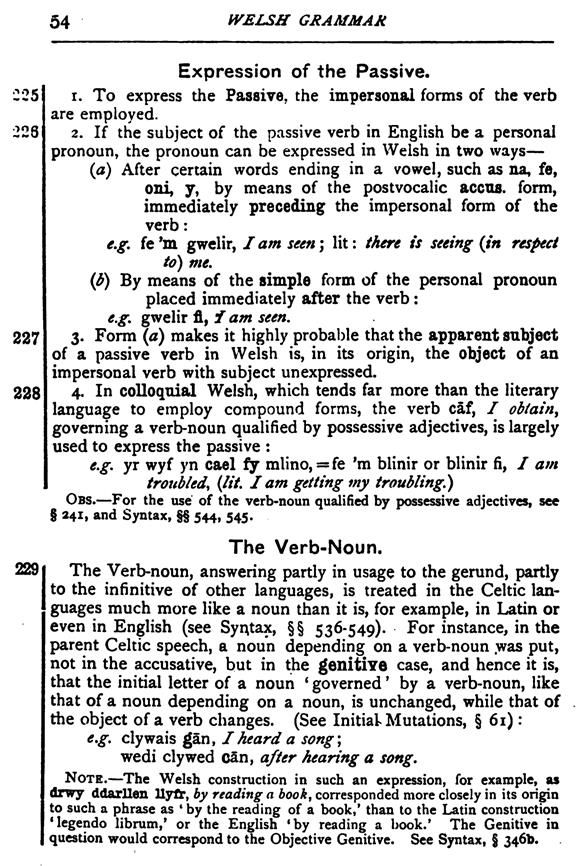

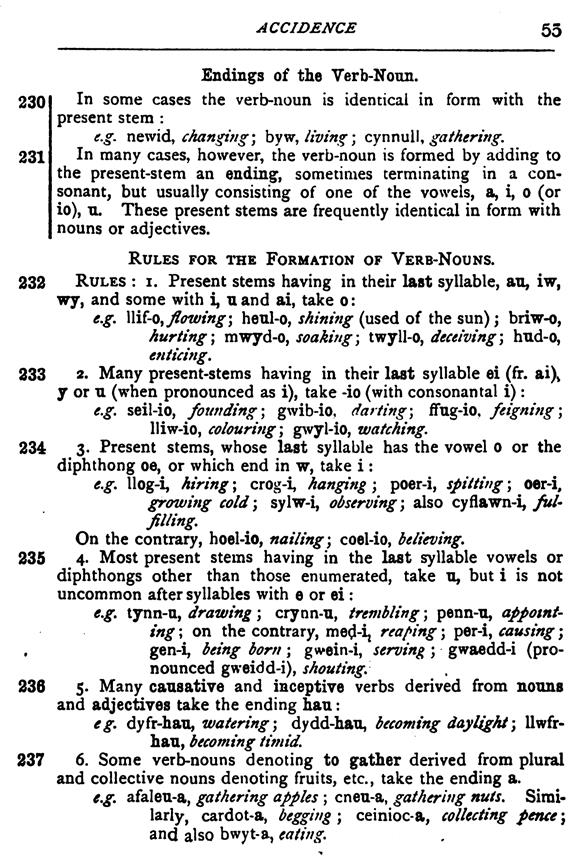

N (en)

O (o)

P (pi)

Ph (ffi)

R (er)

S (es)

T (ti)

Th (eth)

U (u)

W (w)

Y (y)

OBS. - In the Welsh settlement of Patagonia, V is frequently used for F, and

F for Ff.

·····

5 On Sounds

Letters are signs of symbols representing sounds.

In Welsh, the symbols used in the written language represent the sounds of

the spoken language far more accurately than in English: ch, dd, ff, ng, ll,

ph, and th, being counted for this purpose as single letters. Welsh may,

therefore, to all intents and purposes, be siad to be phonetically written.

The only letters which have more than one sound are e, u, and y: - e has, in

some diphthongs, the sound of y [In North Wales only], in others the sound o

u; y has, under certain circumstances, the sound of u; and both u and y have

in some words the sound of i.

·····

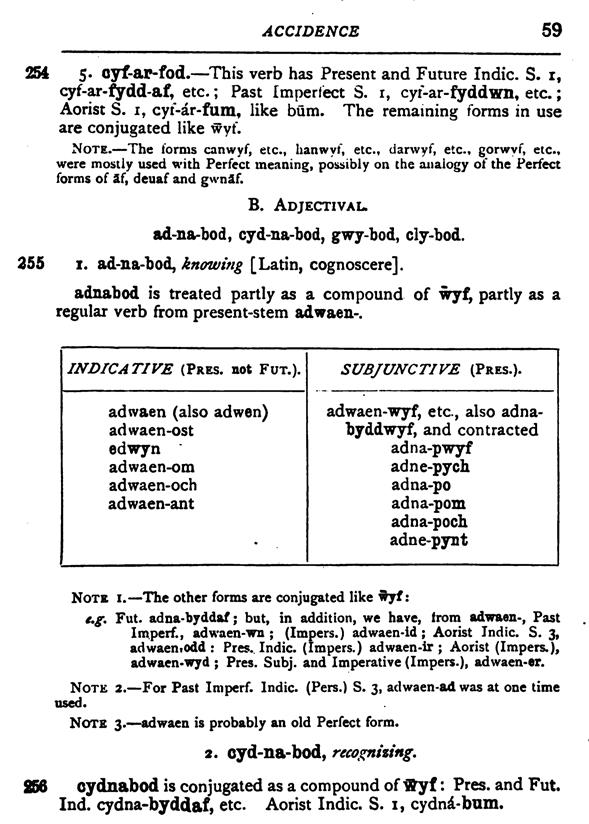

6 Classification of Sounds

Articulate sounds are of two kinds:-

I. Vowel Sounds, produced by vibration of the vocal chords, accompanied by

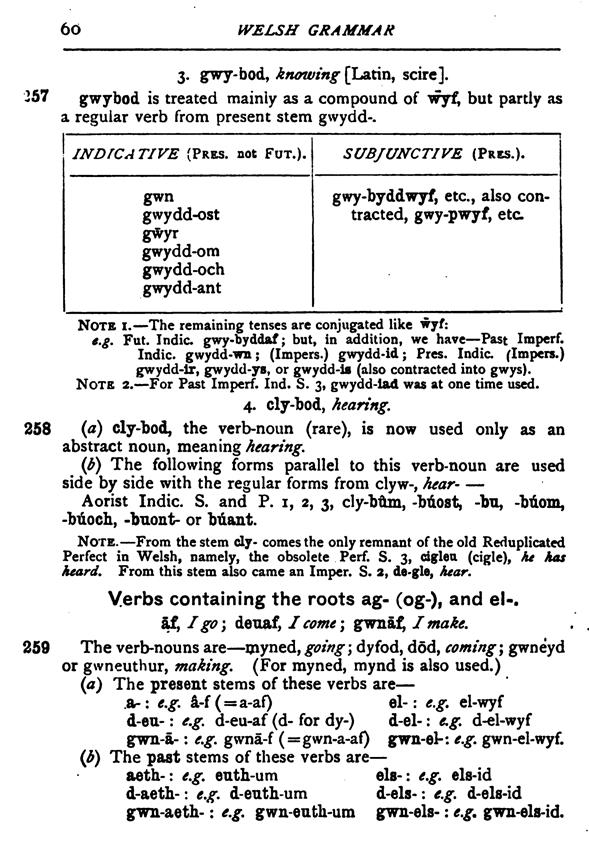

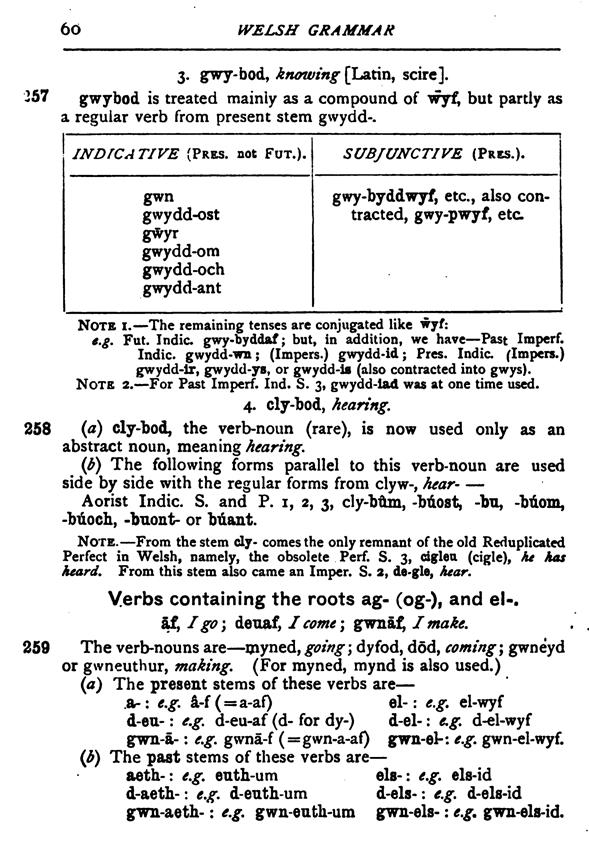

the articulation proper to each vowel.

II. Consonant Sounds, produced by means of the lips (Labials), teeth

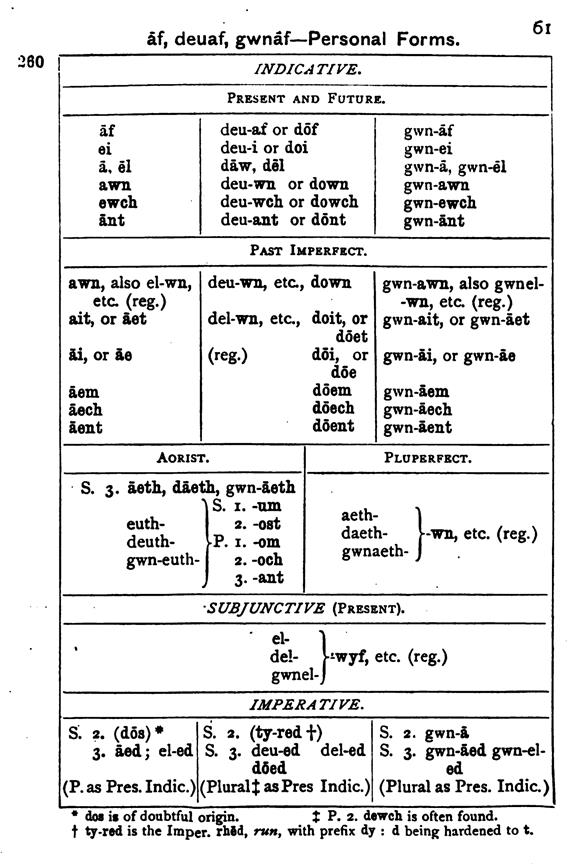

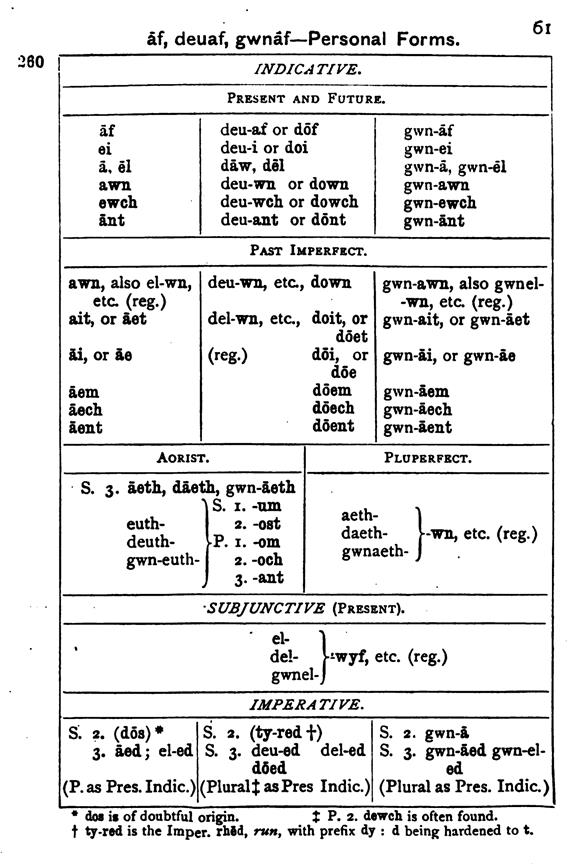

(Dentals), palate (Palatals), throat or back part of the palate (Gutturals),

tongue (Linguals), nose (Nasals), or some combination of these parts, with or

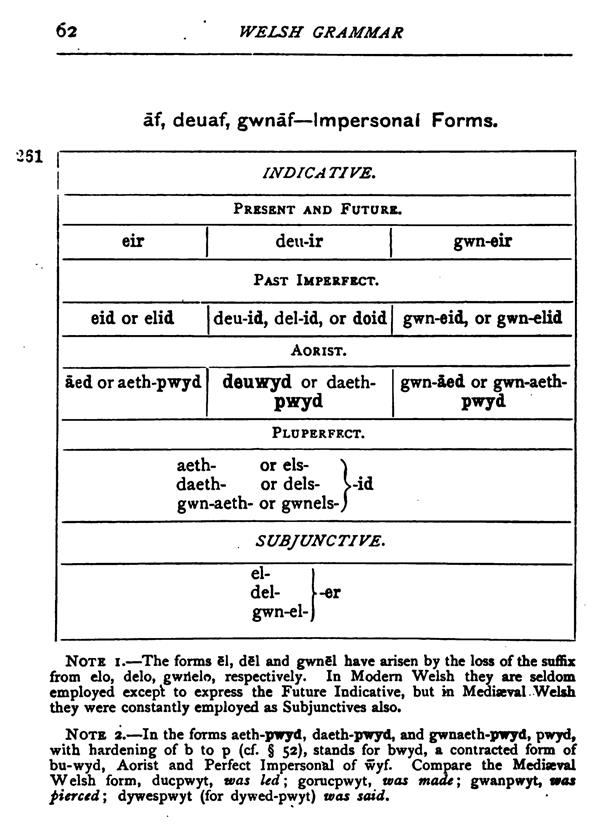

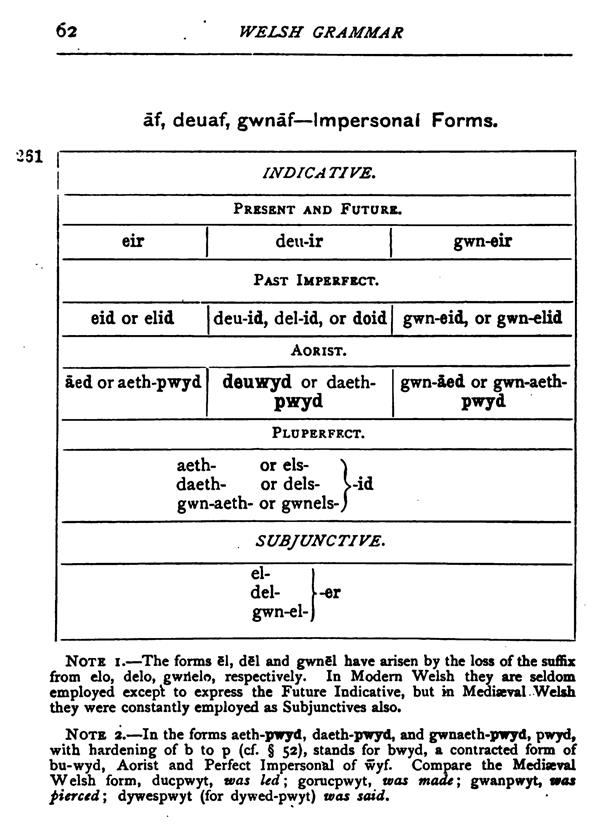

without vibration of the edges of the vocal chords.

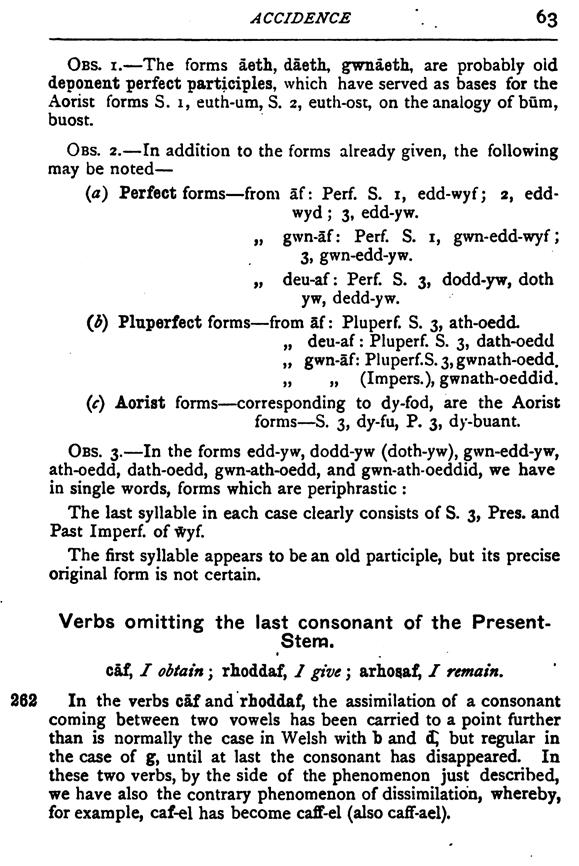

|

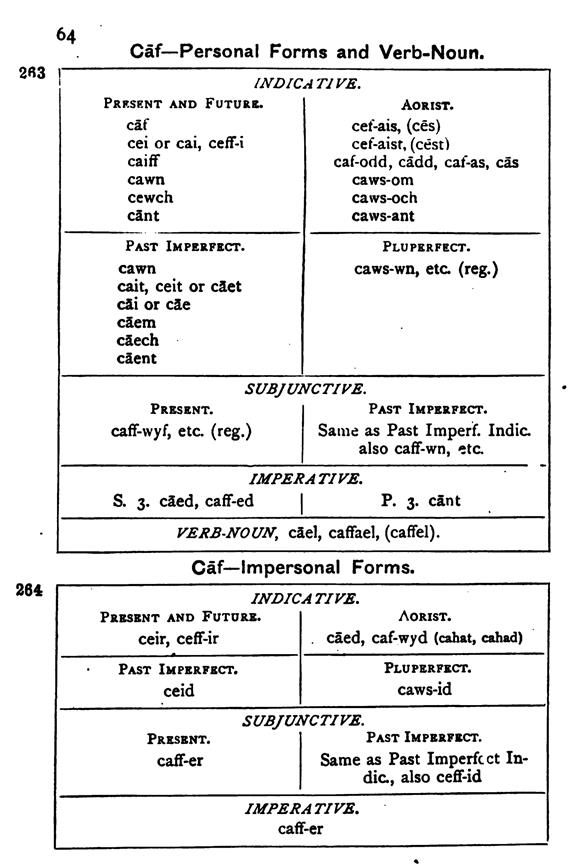

|

|

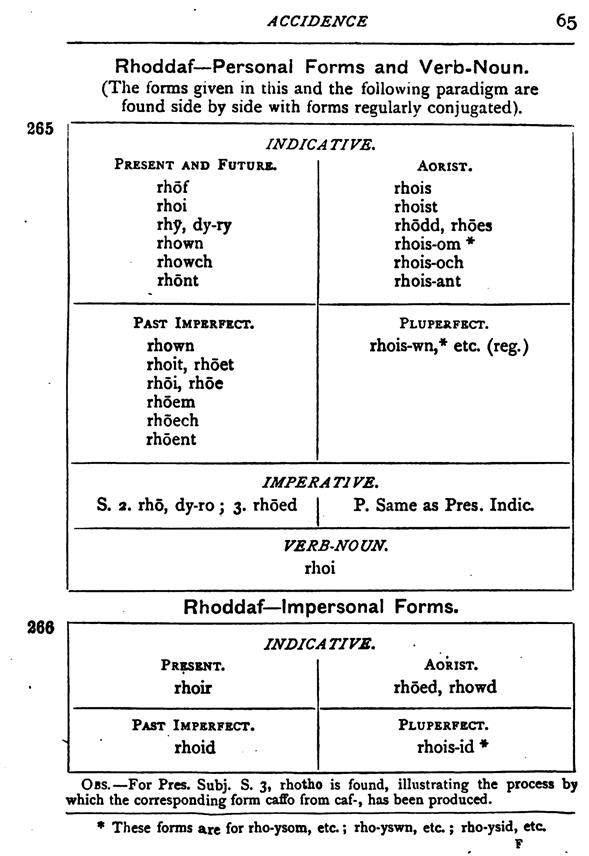

|

|

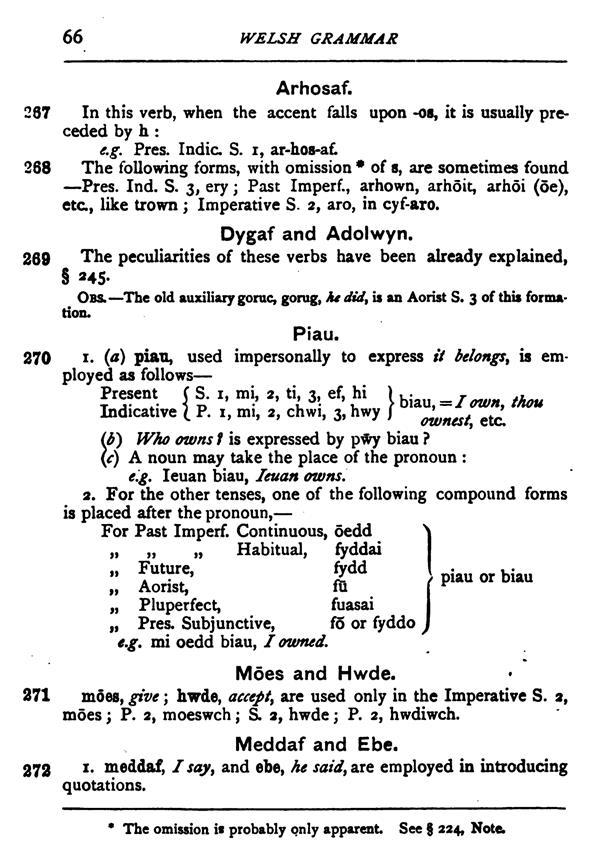

(delwedd F7186) (tudalen 003)

|

3. INTRODUCTION

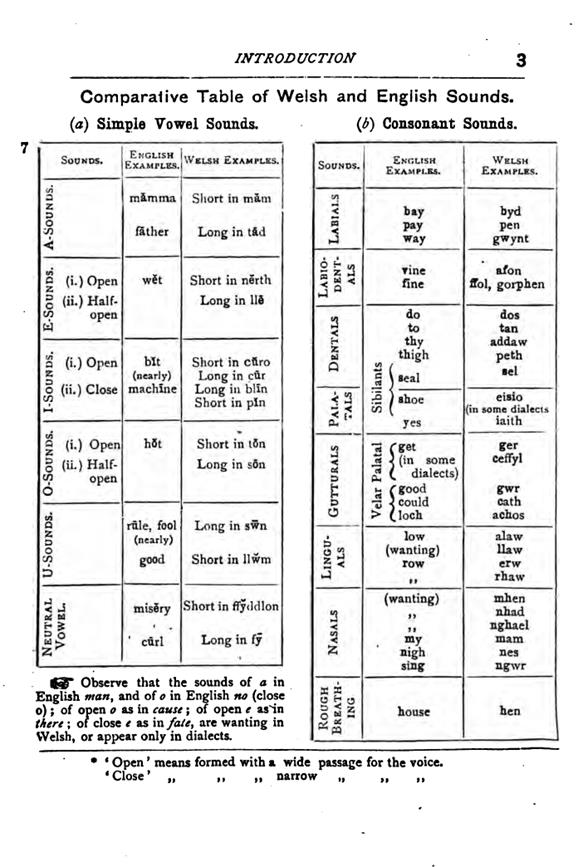

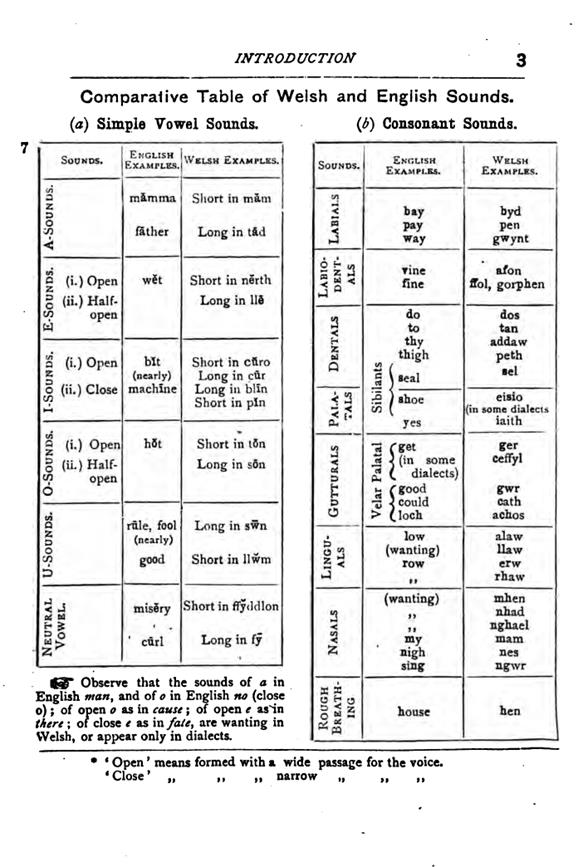

7 Comparative Table of Welsh and English Sounds

·····

(b) Simple Vowel Sounds

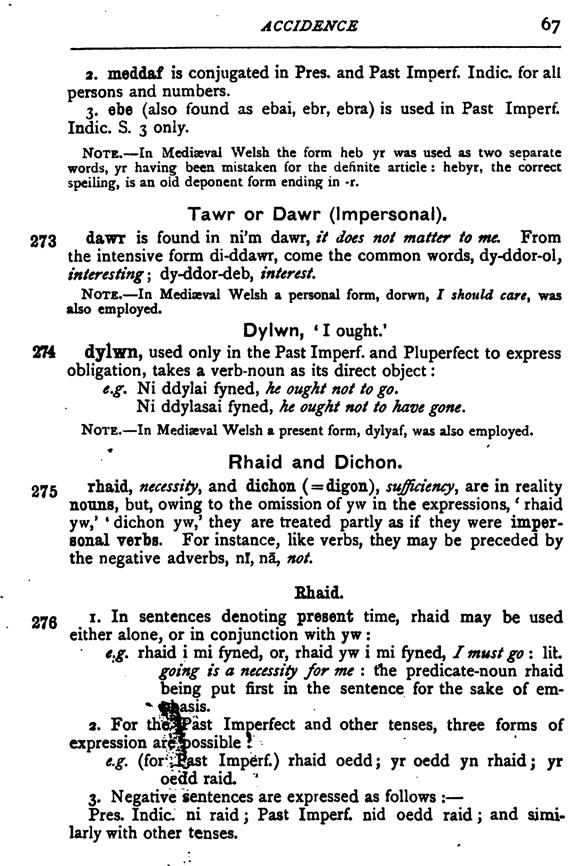

SOUNDS

ENGLISH EXAMPLES

WELSH EXAMPLES

A-SOUNDS

màmma

fâther

short in màm

long in tâd

E-SOUNDS

(i) Open

(ii) Half-open

wèt

short in nèrth

long in llê

I-SOUNDS

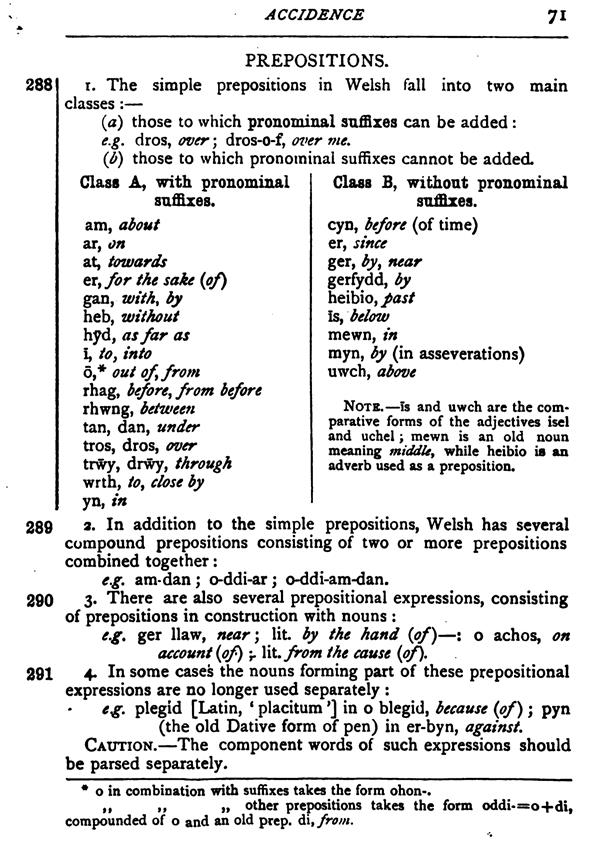

(i) Open

(ii) Close

bìt (nearly)

machîne

Short in cùro / Long in cûr

Long in blîn / Short in pìn

O-SOUNDS

(i) Open

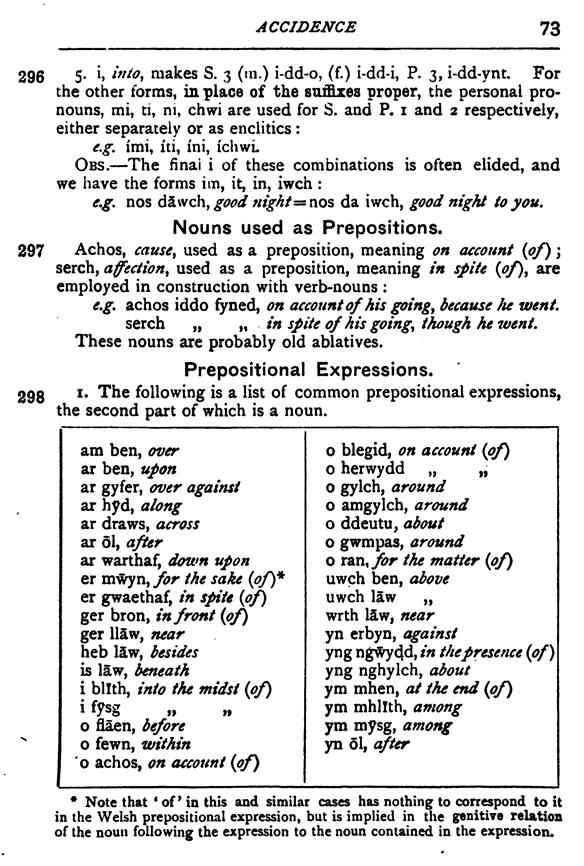

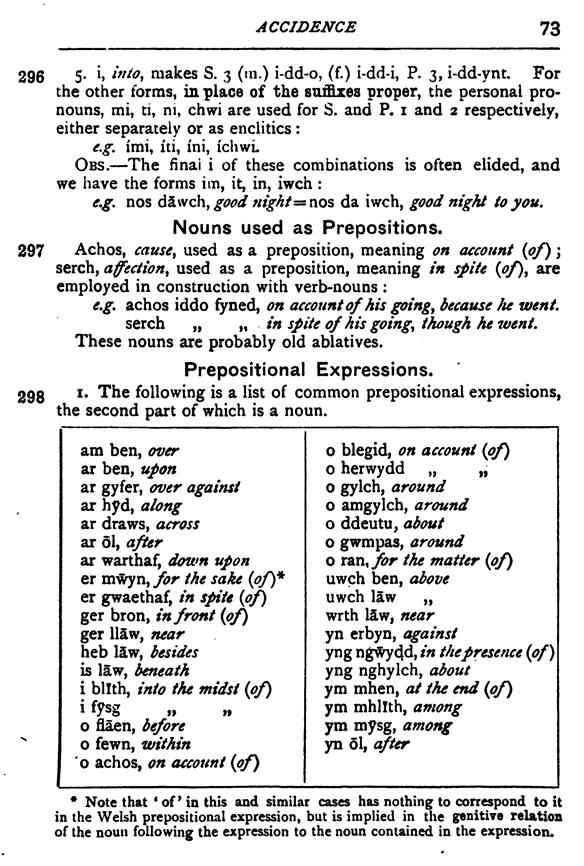

(ii) Half-open

hòt

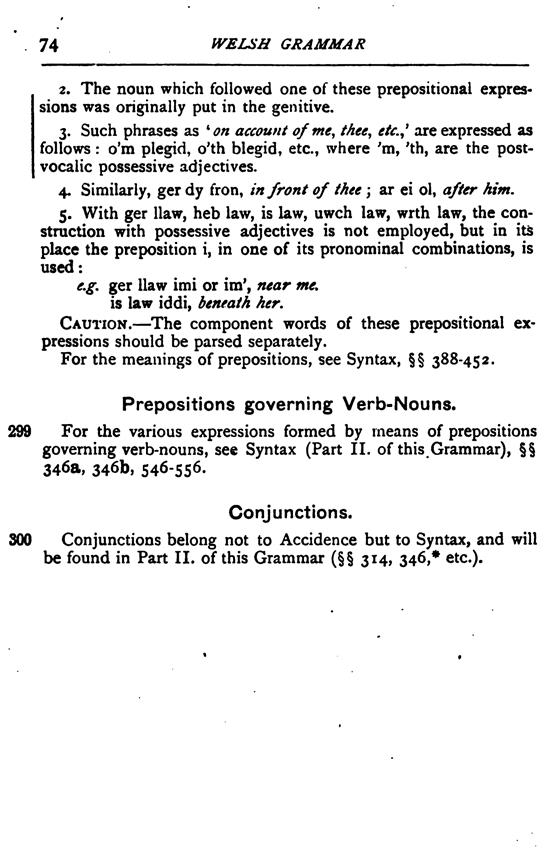

Short in tòn

Long in sôn

U-SOUNDS

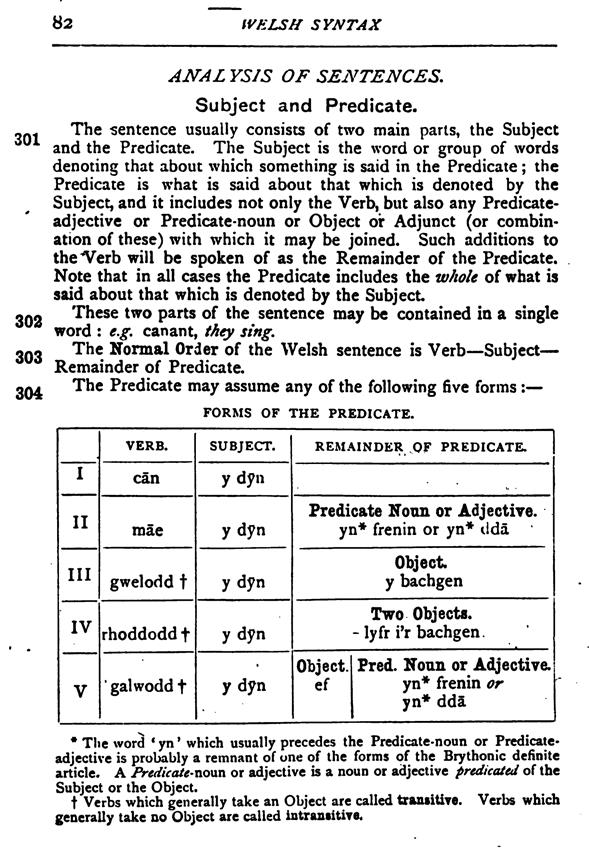

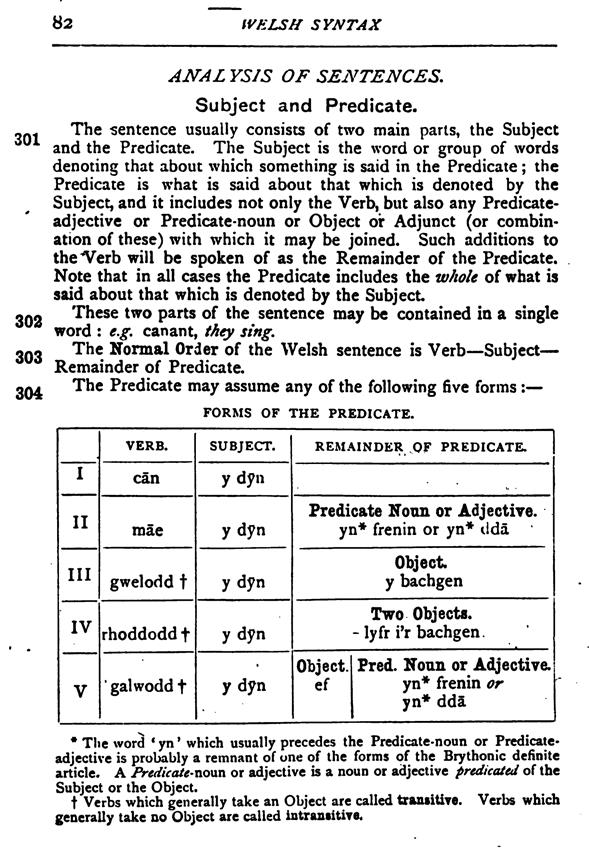

rûle, fool (nearly)

good

Long in sŵn

Short in llw`m

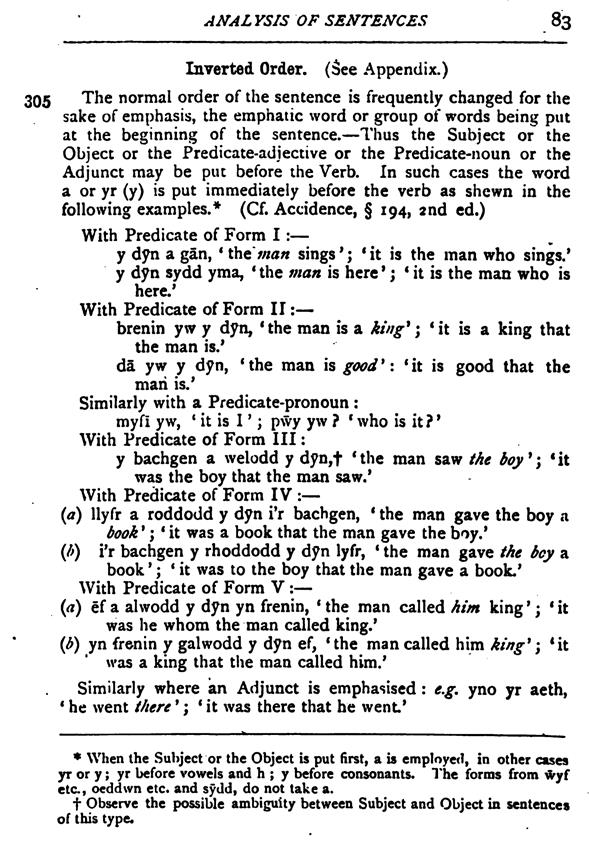

NEUTRAL VOWEL

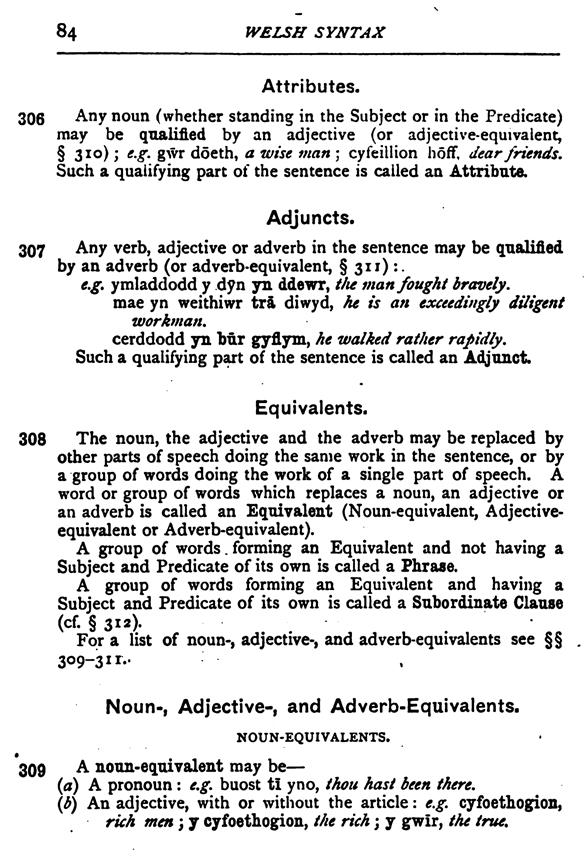

misèry

cûrl

Short in ffy`ddlon

Long in fŷ

Observe that the symbols of a in English man, and of o in English no (close

o); of open o as in cause; of open e as in there; of close e as in fate, are

wanting in Welsh, or appear only in dialects.

‘Open’ means formed with a wide passage for the voice

‘Close’ means formed with a narrow passage for the voice

·····

(b) Consonant Sounds

SOUNDS

ENGLISH EXAMPLES

WELSH EXAMPLES

LABIALS

bay

pay

way

byd

pen

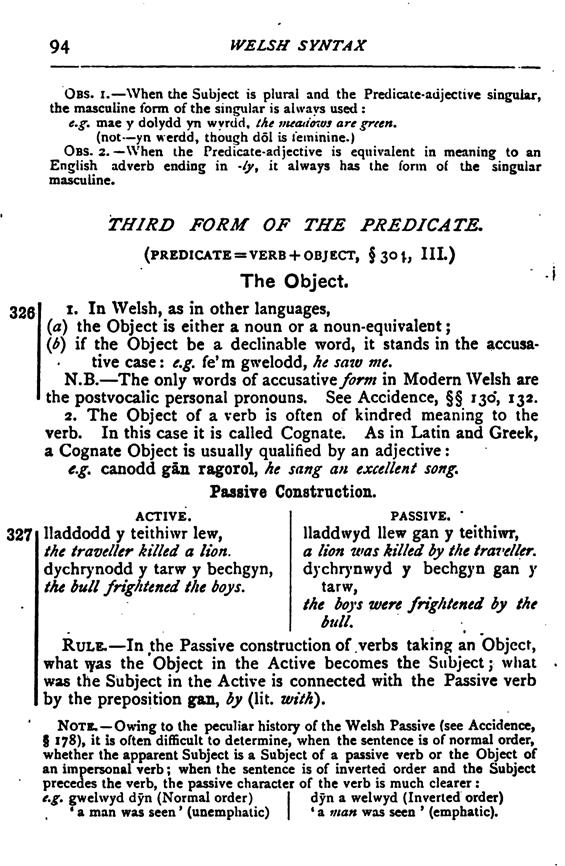

gwynt

LABIO-DENTALS

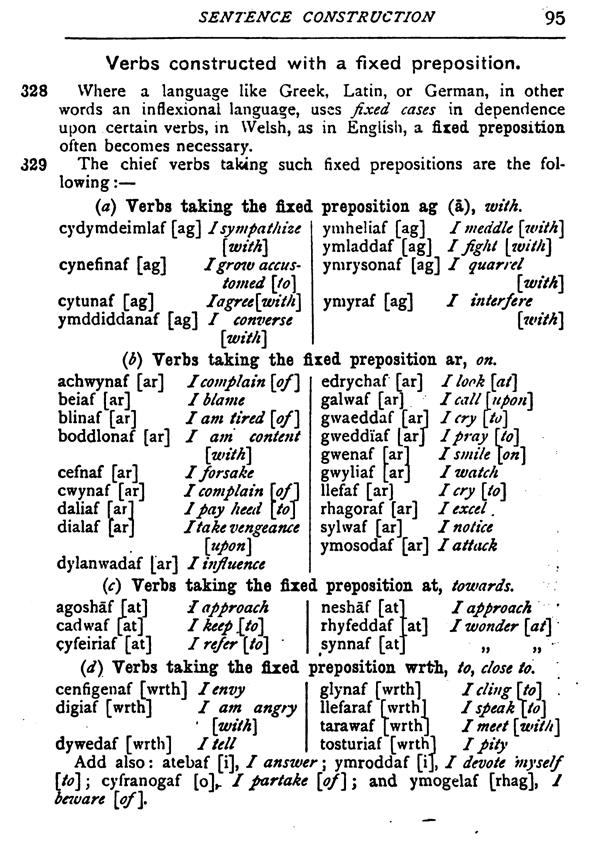

vine

fine

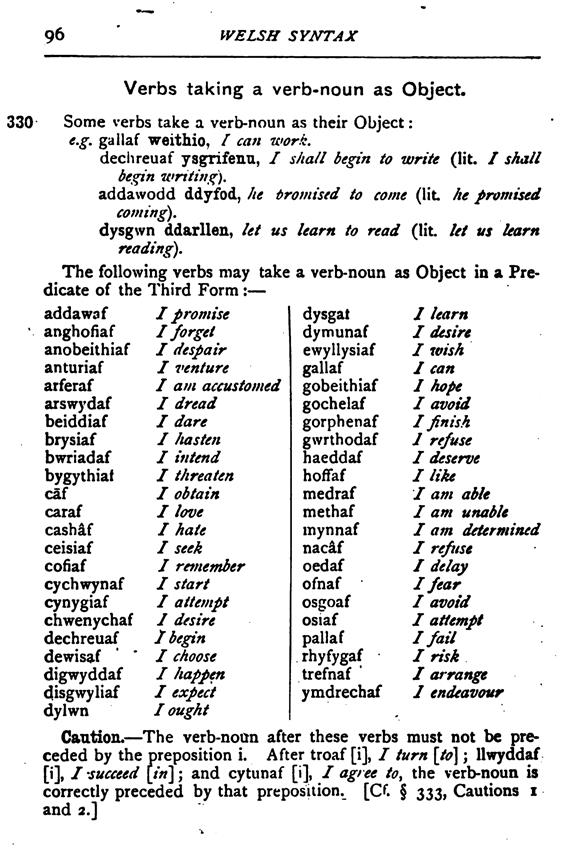

afon

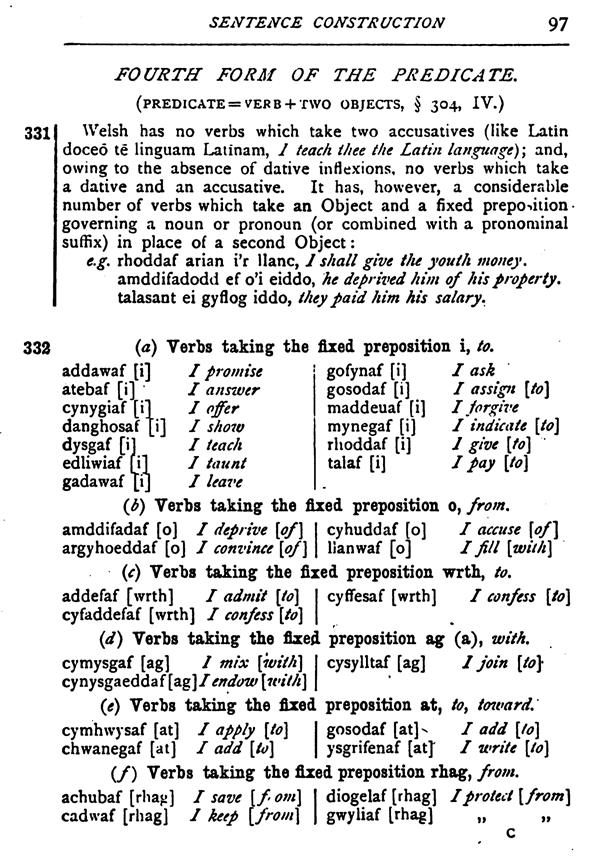

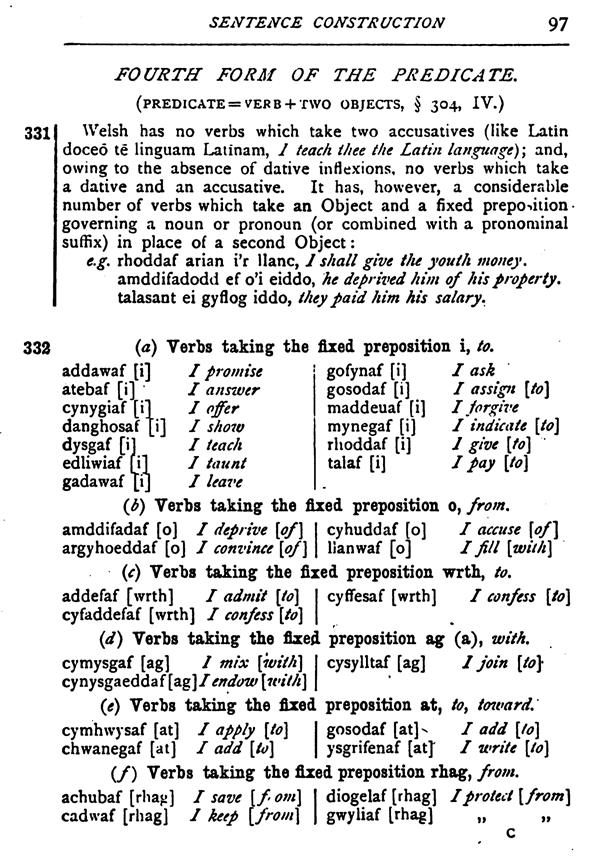

ffol, gorphen

DENTALS

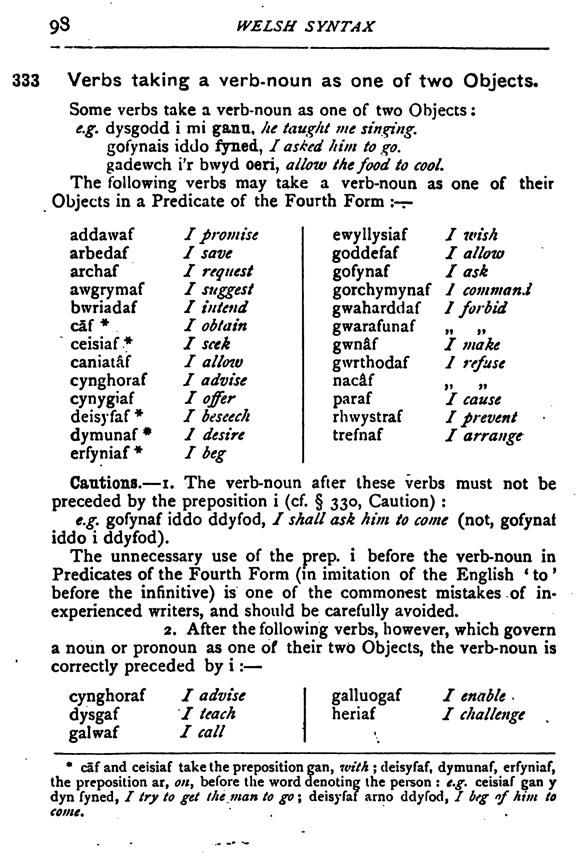

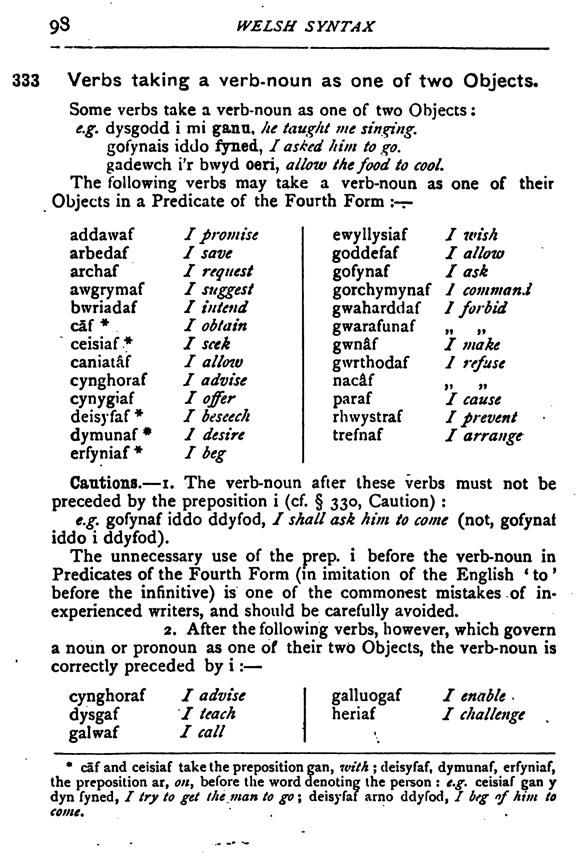

·

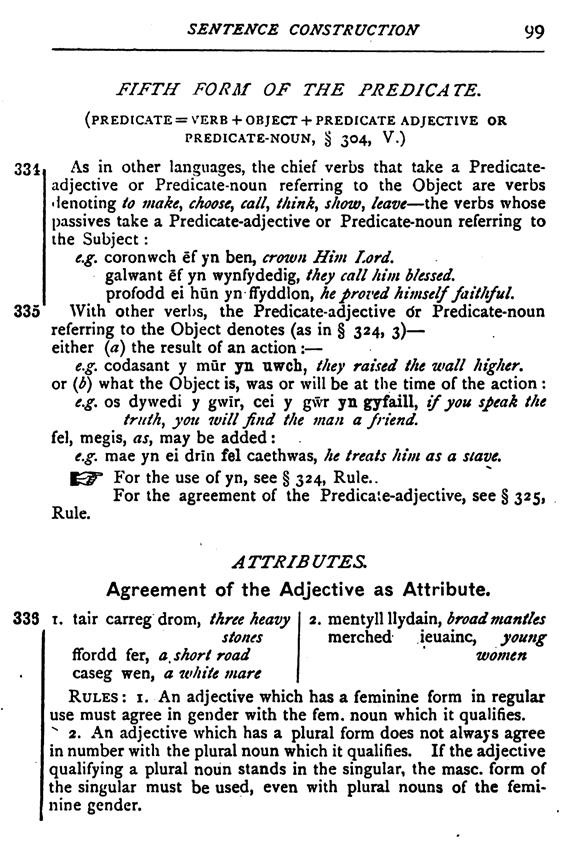

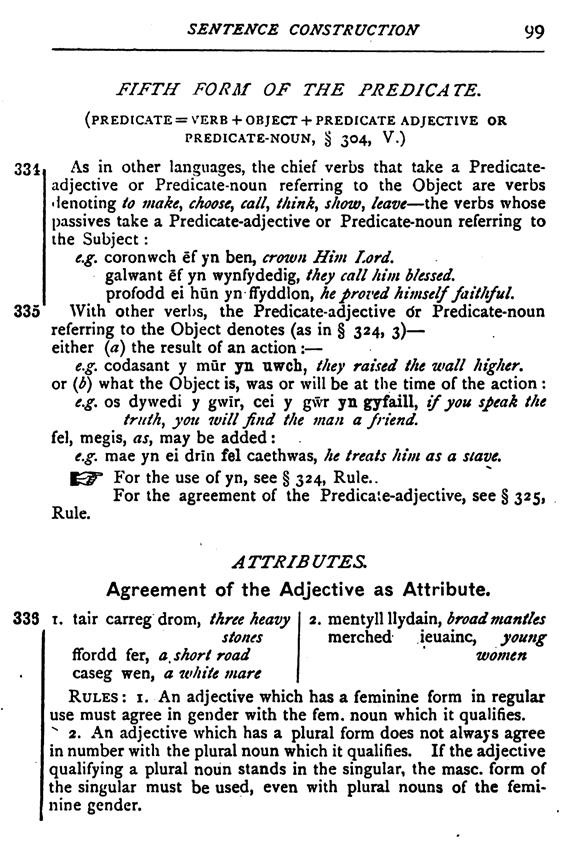

·

·

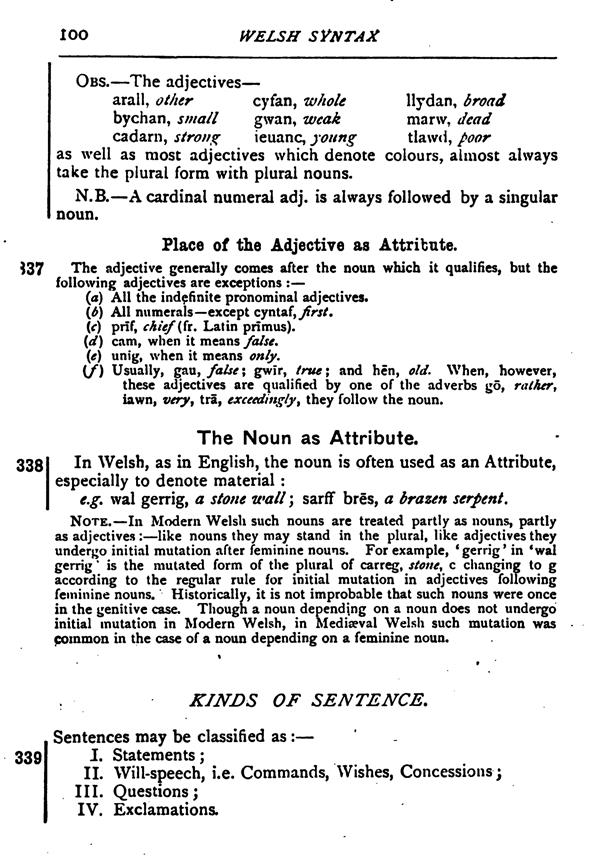

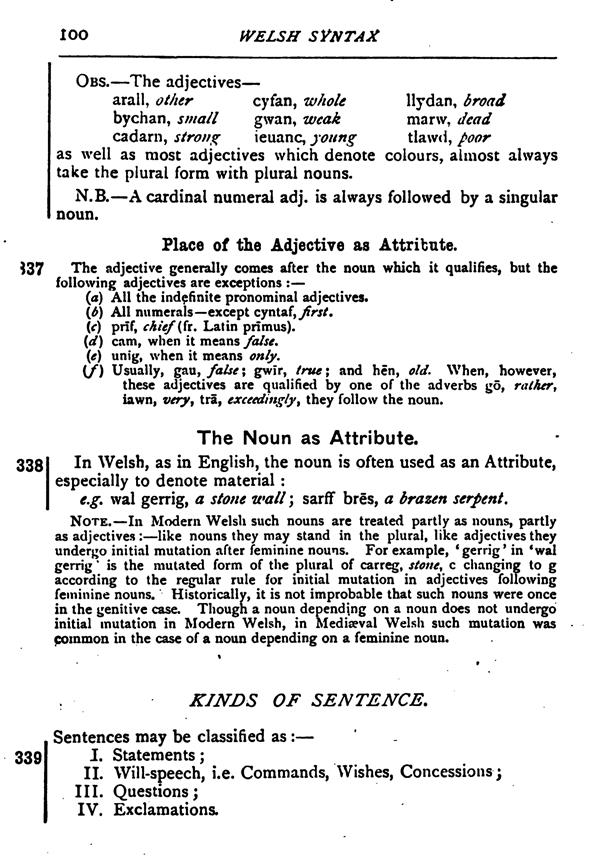

·

SIBILANT

do

to

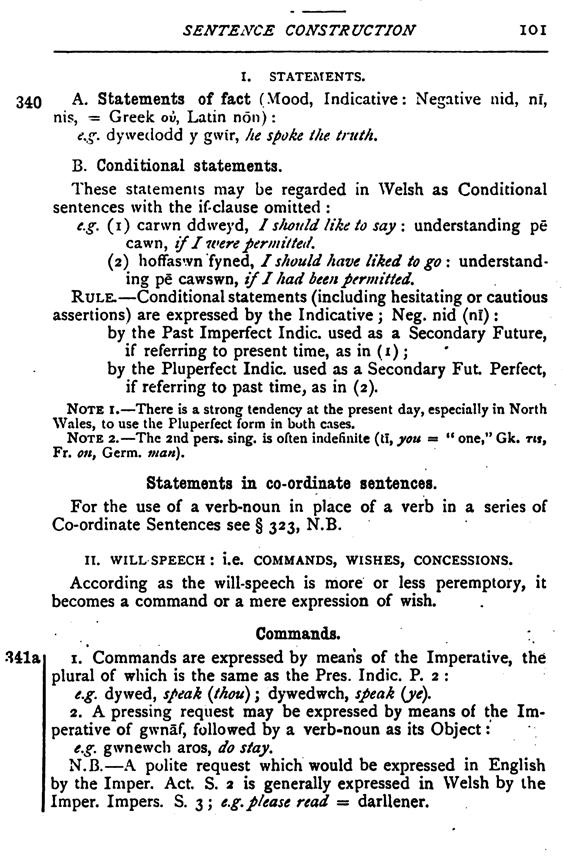

thy

thigh

seal

dos

tan

addaw

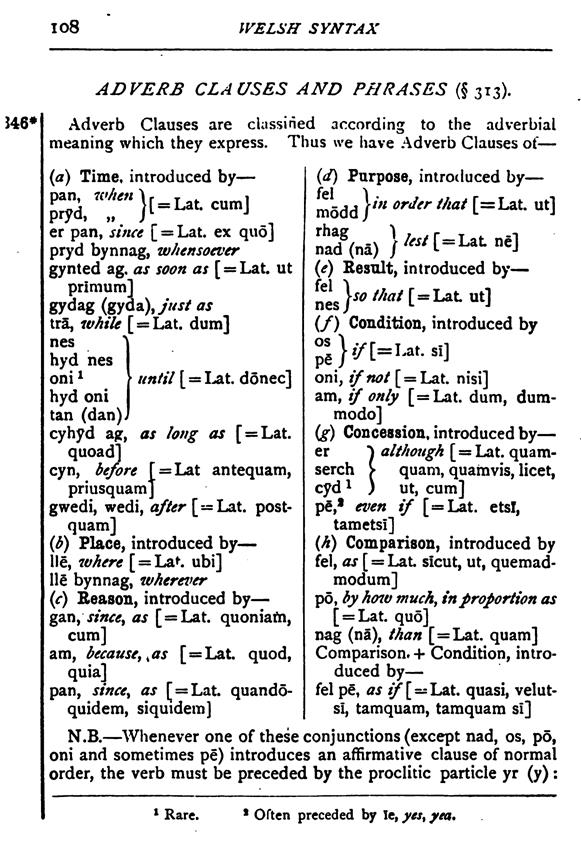

peth

sel

PALATALS

SIBILANT

shoes

yes

eisio (in some dialects)

iaith

GUTTERALS

PALATAL

PALATAL

VELAR

VELAR

VELAR

get

(in some dialects)

good

could

loch

ger

ceffyl

gwr

cath

achos

LINGUALS

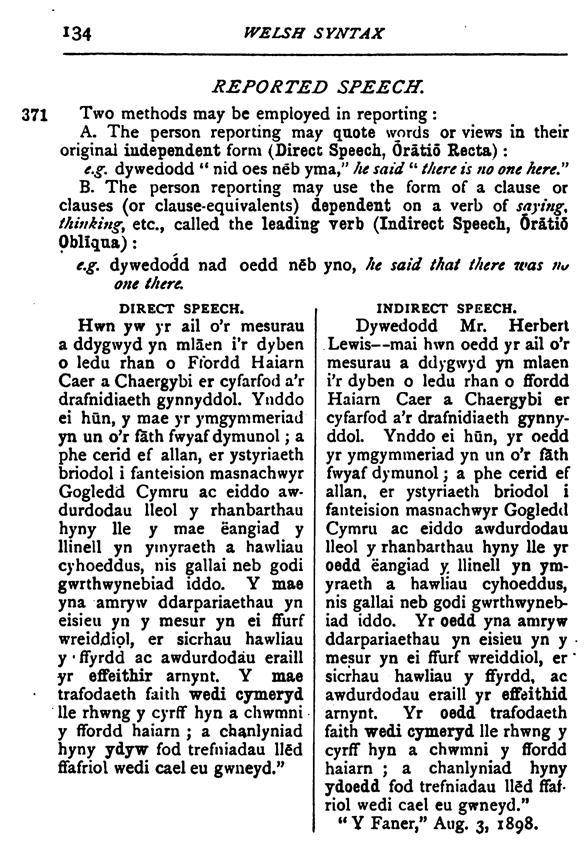

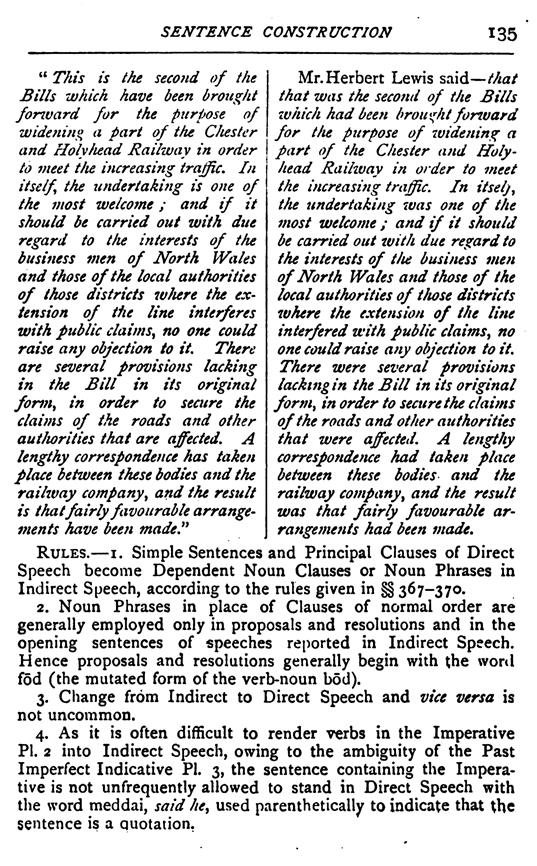

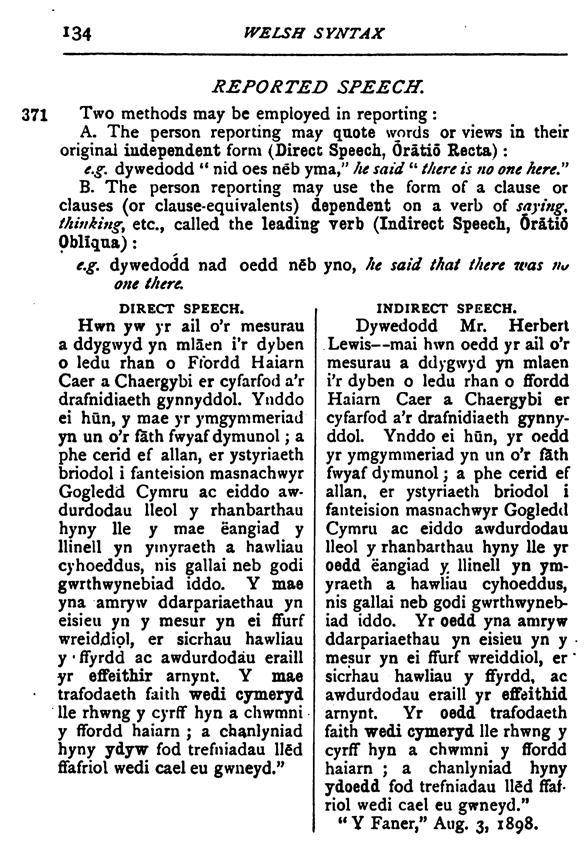

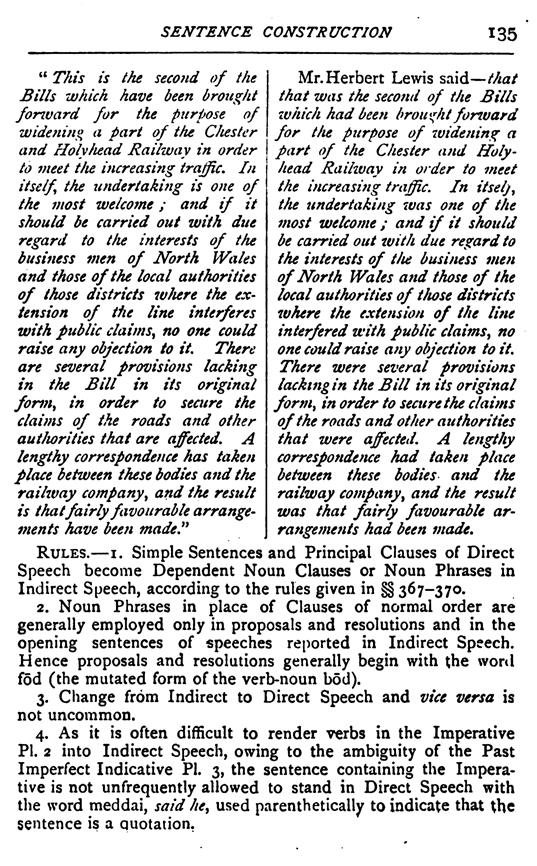

low

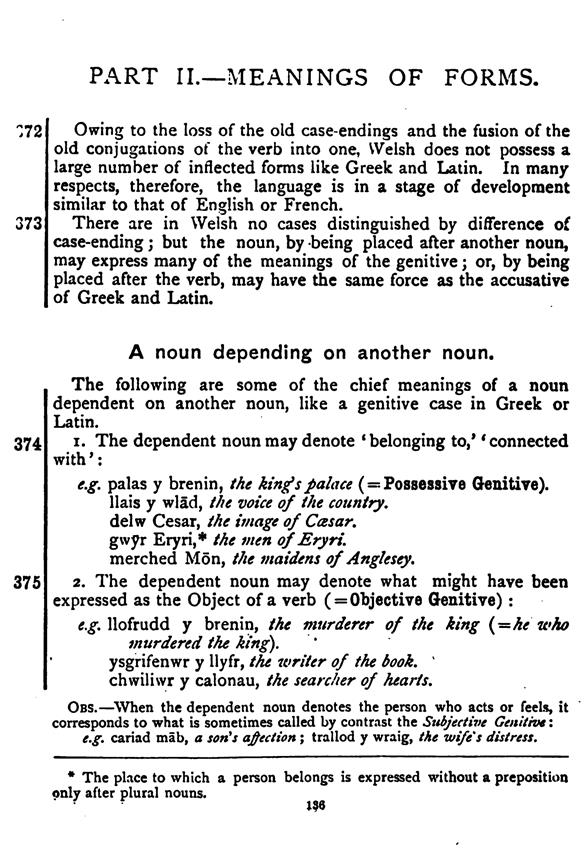

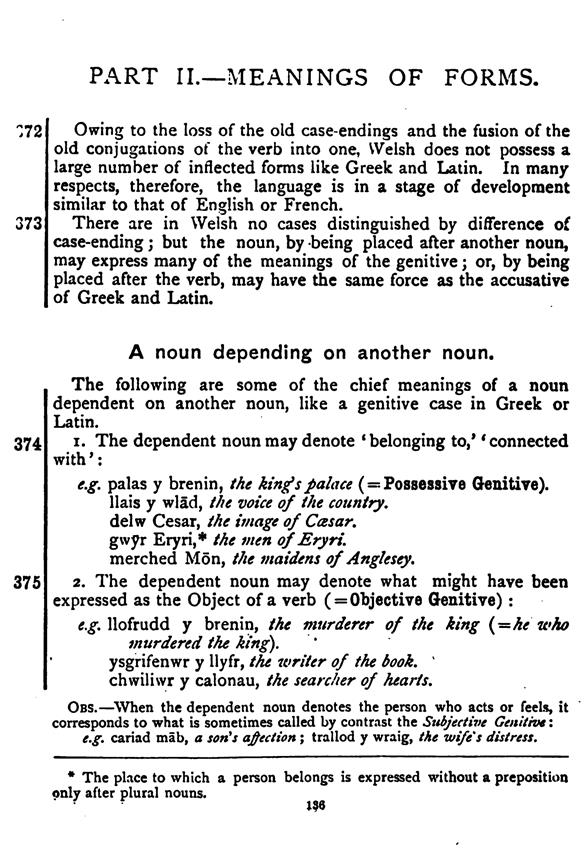

(wanting)

row

(wanting)

alaw

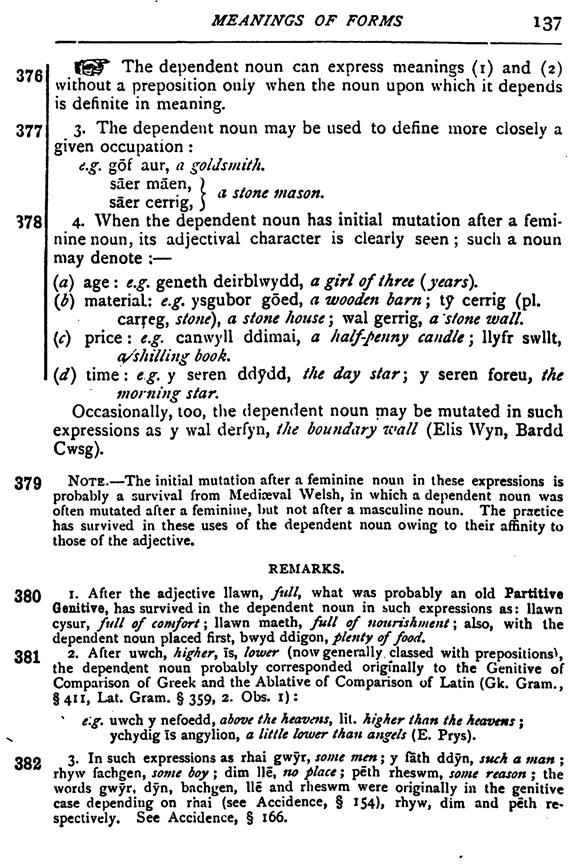

llaw

erw

rhaw

NASALS

(wanting)

(wanting)

(wanting)

my

nigh

sing

mhen

nhad

nghael

mam

nes

ngwr

ROUGH BREATHING

house

hen

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7187) (tudalen 004)

|

4 WELSH GRAMMAR

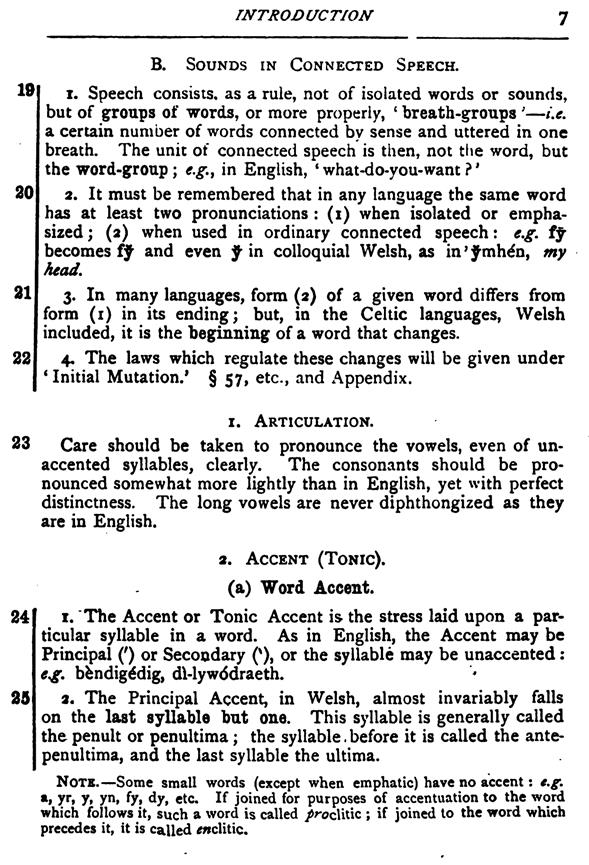

8 NOTE 1. -y is

pronounced like Welsh u:

-

·····(a) In monosyllables:

e.g. sŷdd, is; dyn, man; except in the

proclitics yr (ydd); y; ys; fy, my; dy, they; and myn, by (used in

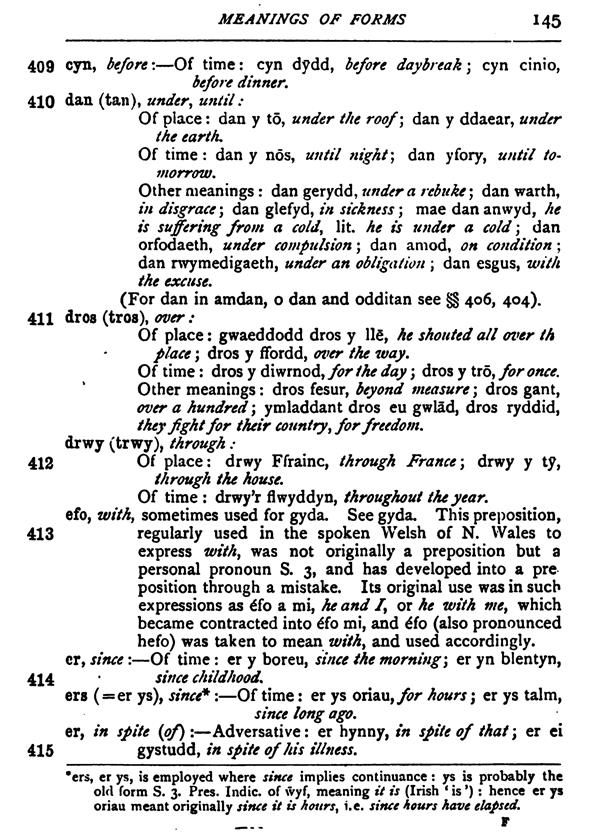

asserverations). (A proclitic is a word which has no accent of its own, but

is joined for the purpose of accentuation to the words which follows it)

·····(b) In the final

syllable of a word of more

than one syllable: e.g. sefyll,

standing; estyn,

reaching; perthyn,

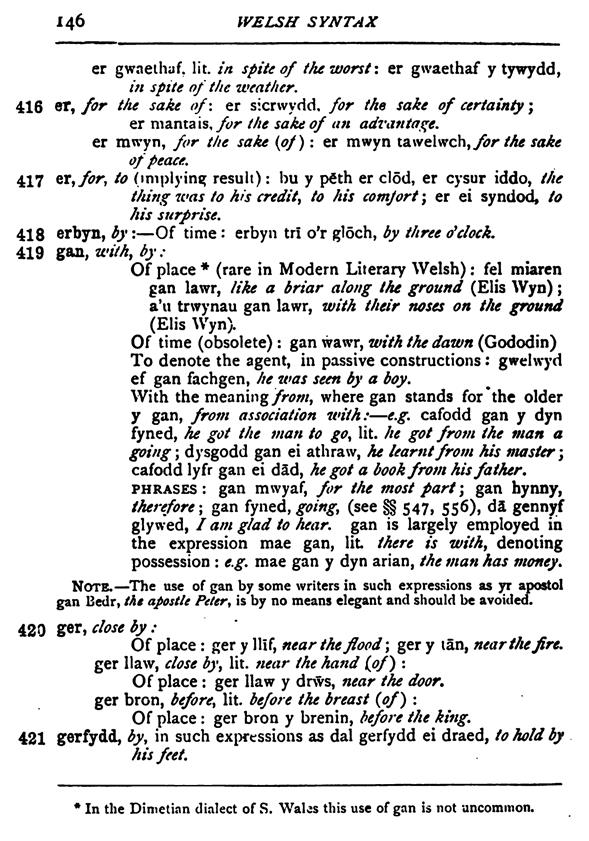

belonging

·····(c) In the last

syllable but one of a word, before a vowel: e.g. hyawdl, eloquent; dyall, understanding.

·····(d) In the last

syllable but one, or the last

syllable but two of many

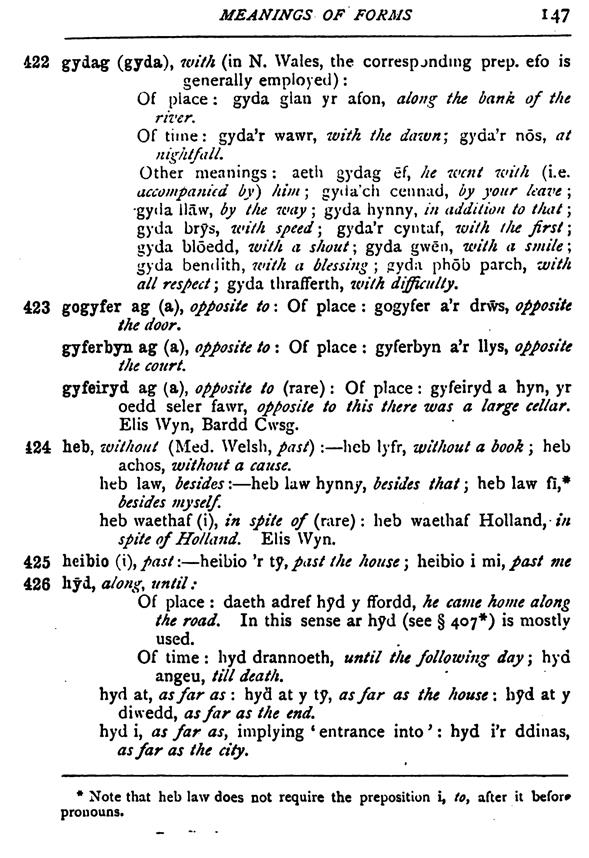

words, when it is preceded by w: e.g. gwyneb, face; gwyddau, geese; gwyntoedd, winds.

····

9 NOTE 2. - In the

greater part of mid-Wales and South-Wales u is pronounced as i, and sometimes as y

·····

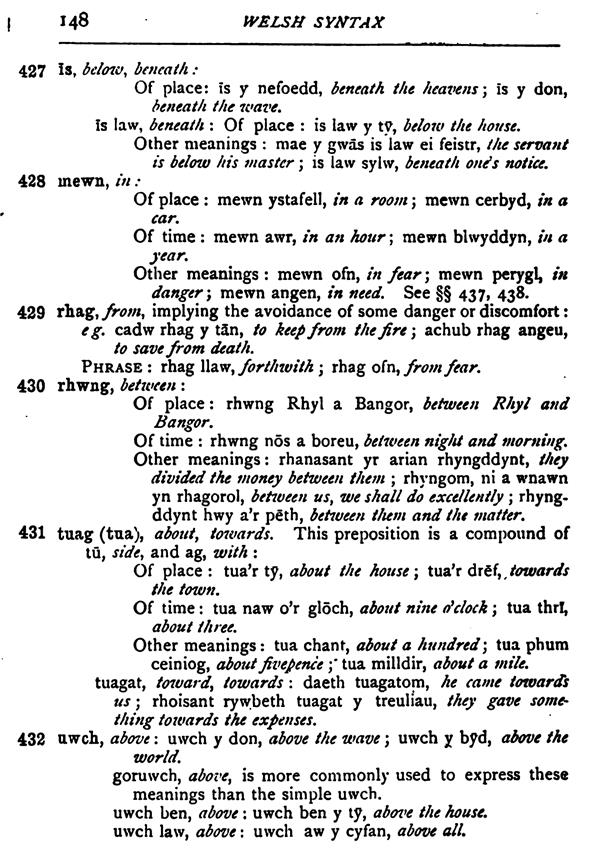

10 NOTE 3. - u is pronounced as i throughout Wales in –

ugain,

deugain,

union,

rhÿwun,

cynnull,

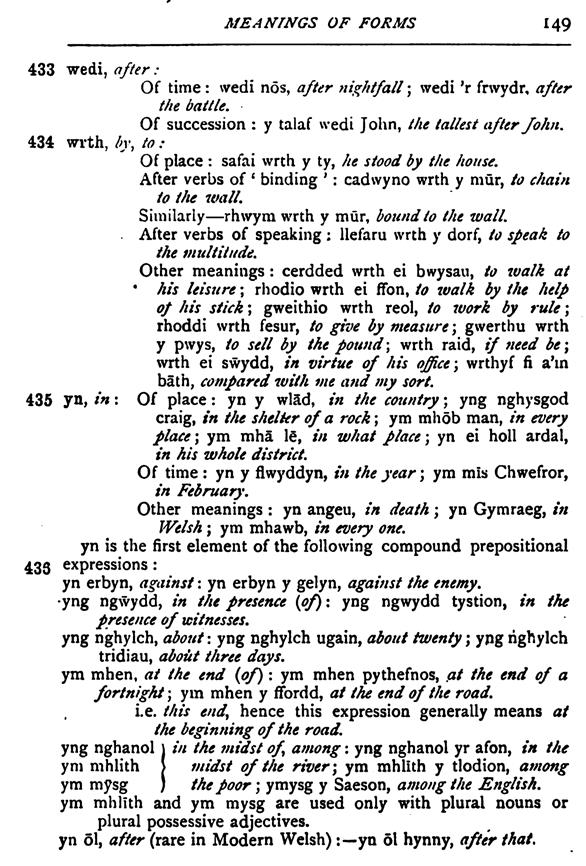

bugail,

duwiol,

annuwiol,

ieuenctid,

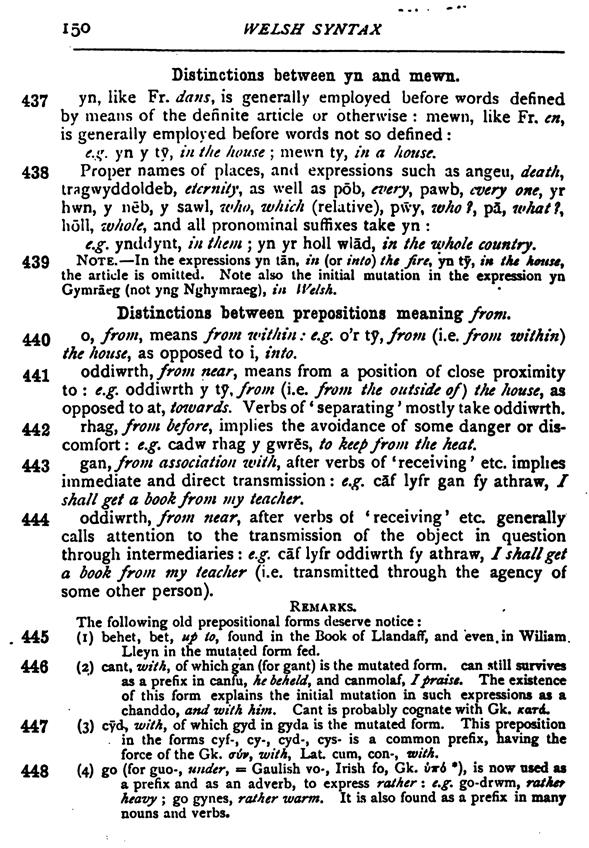

diluw,

trueni,

Deheudir,

cuddio

·····

11 NOTE 4. - y is pronounced as i throughout Wales in - disgybl,

disgyn,

diwyg,

diwygio,

diwygwyr,

dilyn,

gilydd,

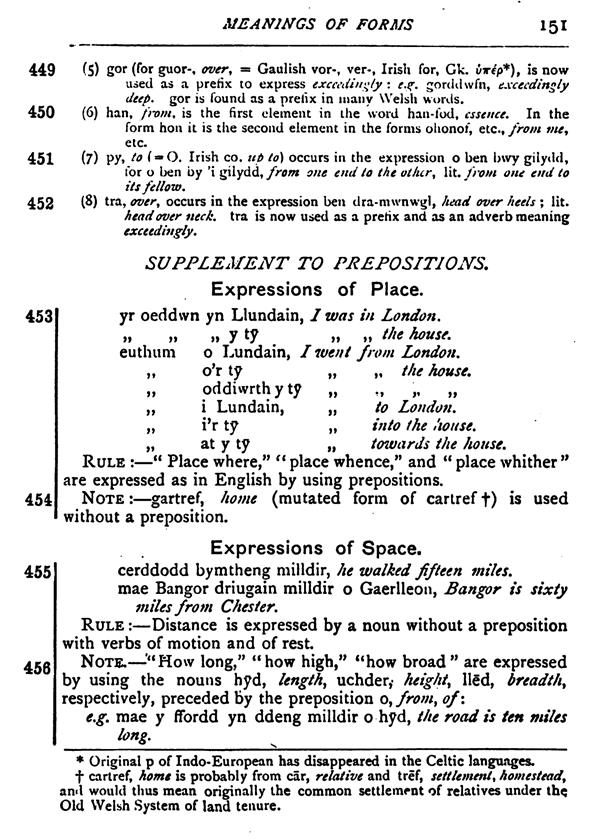

megys,

dinystr,

disgwyl,

gyda,

meddyg,

gloywi,

tebyg,

ceryg,

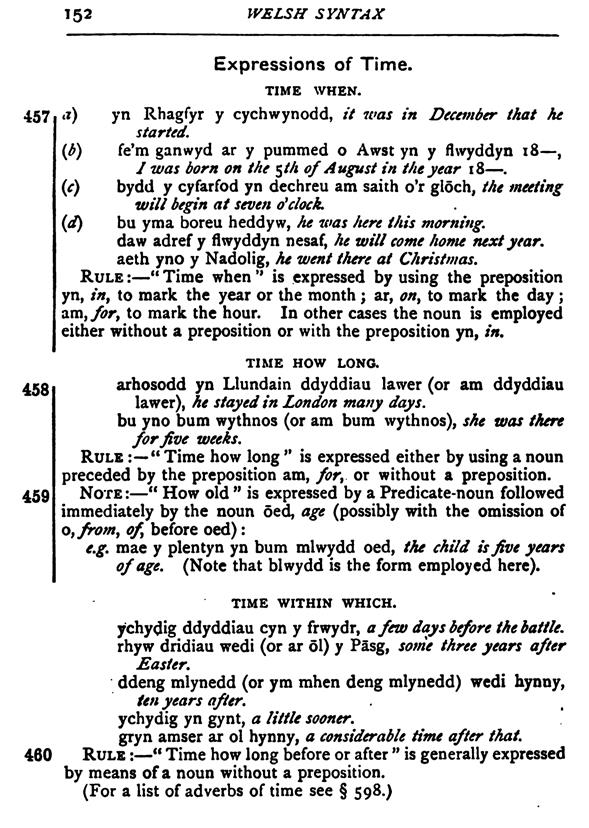

llewyg,

llewys,

plisgyn,

dychymyg,

amryw,

rhywun,

cyw,

yw,

ydyw,

efengyl,

gwylio,

dryw,

cyfryw,

ystryw,

distryw,

heddyw,

benyw,

rhelyw,

llinyn,

menyg,

diddym.

This occurs either

(a) when the vowel of the preceding syllable is i; or

(b) when the y is preceded or followed by g; or

(c) when the y is followed by w.

NOTE 5. - ll seems to be pronounced by pressing the

lower side of the front part of the tongue against the roof of the mouth and

emitting the breath over its sides, without vibration of the vocal chords.

NOTE 6. - w and i are used both as vowels and as

consonants: e.g., in gwynt and iaith w and i are consonants

·····

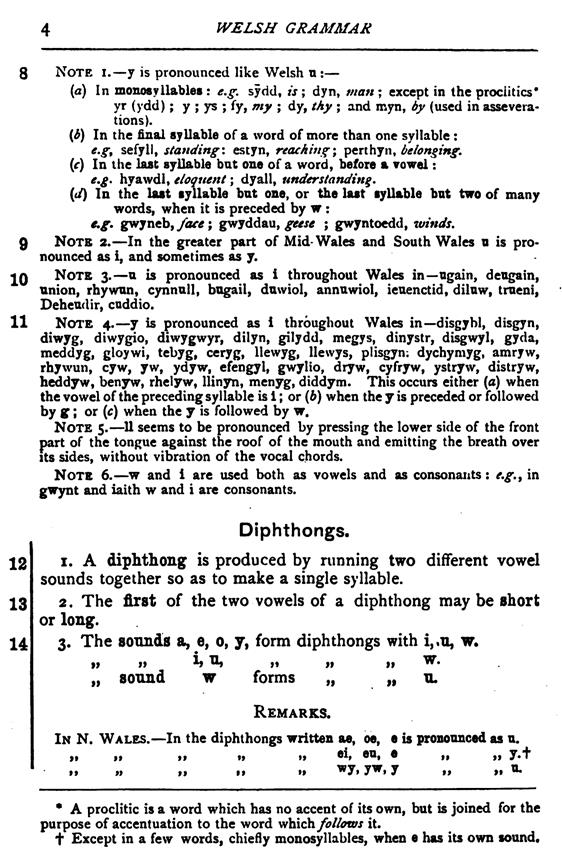

(c) Diphthongs

12 1. A diphthong is

produced by running two different vowel sounds together so as to make a

single syllable.

·····

13 2. The first of the

two vowels of a diphthong may be short or long.

·····

14 3. The sounds e,o,y form diphthongs with i,u,w. The sounds i,u form diphthongs with w. The sound w forms diphthongs with u.

·····

REMARKS.

IN N. WALES. - In the

diphthongs written ae, oe, e is pronounced as u. In the diphthongs written ei, eu, e is pronounced as y. (Except in a few words, chiefly

monosyllables, where e has its own sound). In the

diphthongs written wy, yw, y is pronounced as u.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7188) (tudalen 005)

|

5 INTRODUCTION

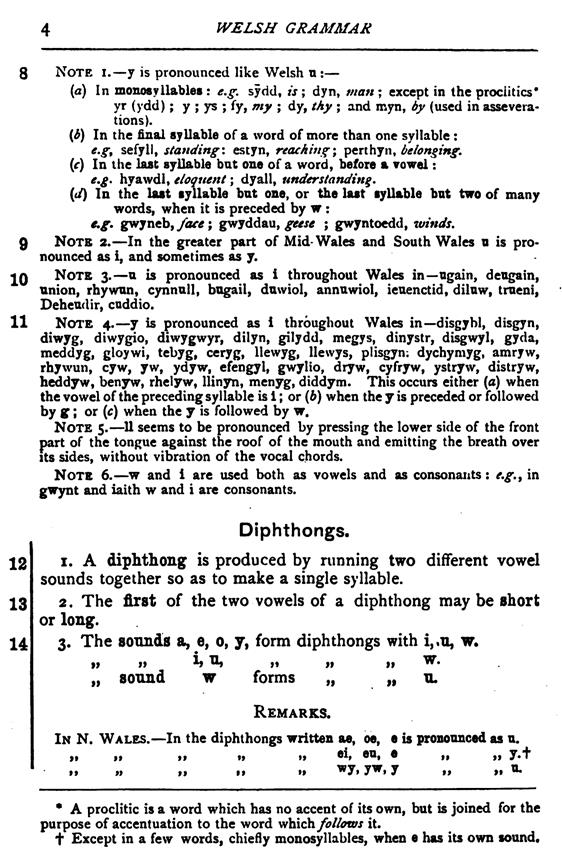

15 Tables of Diphthongs

A-Diphthongs

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

ài

âi

gwaith

â’i

àu

àu

âu (In North Wales only)

âu

aur

hiraeth

gwâudd

câe

àw

âw

awr

llâw

·····

E-Diphthongs

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

àe

ein

èu

èu

gweu

teyrn (The name of the distict Lleyn is prnounced Llûn)

èw

êw (In North Wales only)

blewyn

llew

·····

I-Diphthongs

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

ìw

lliw

·····

O-Diphthongs

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

òi

troi

òu

òu

ôu

o’u

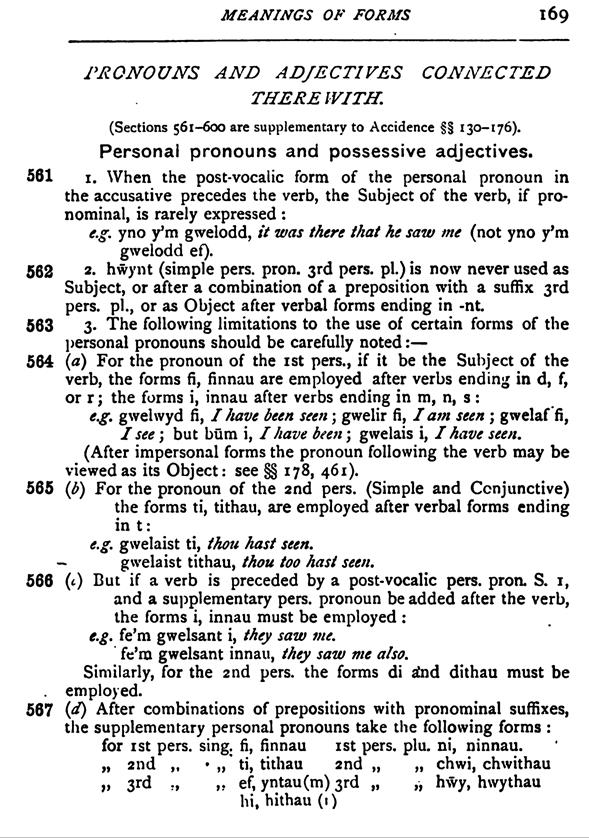

oerach

ôed

òw

dowch

·····

U-Diphthongs

SOUNDS

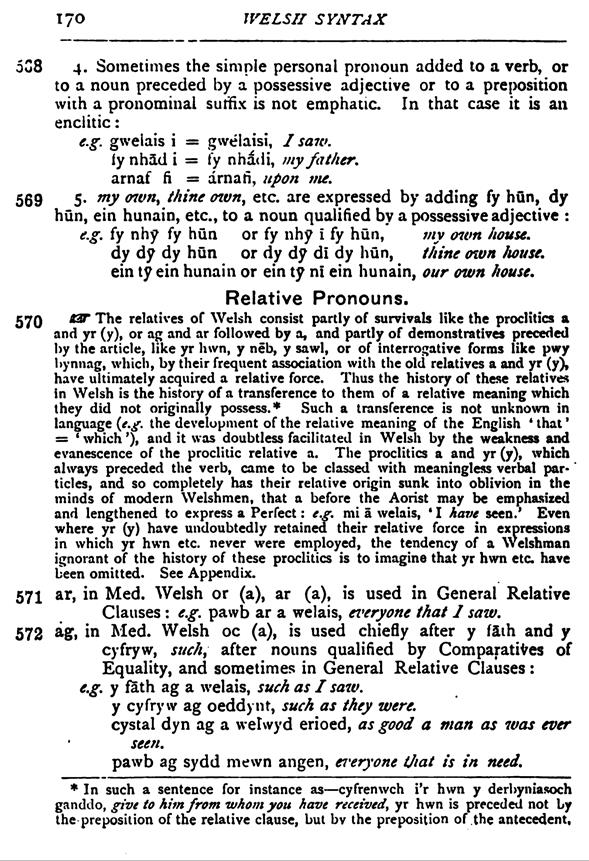

EXAMPLES

ùw

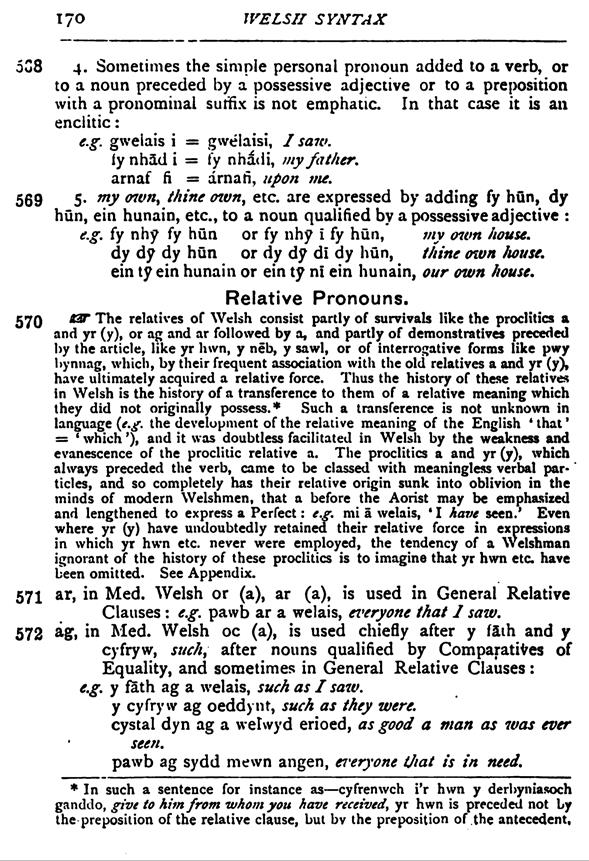

ùw

Duw

byw

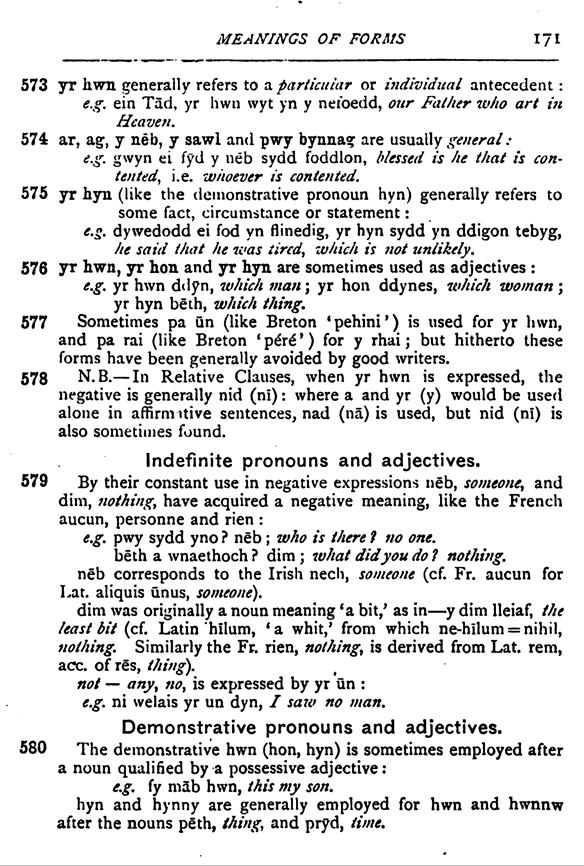

·····

W-Diphthongs

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

ŵu

ŵu

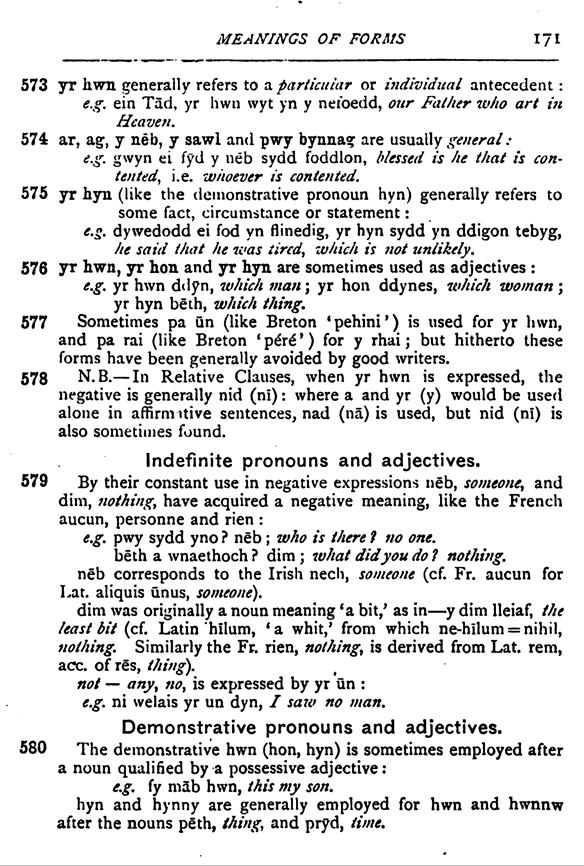

bwydo

rhŵyd

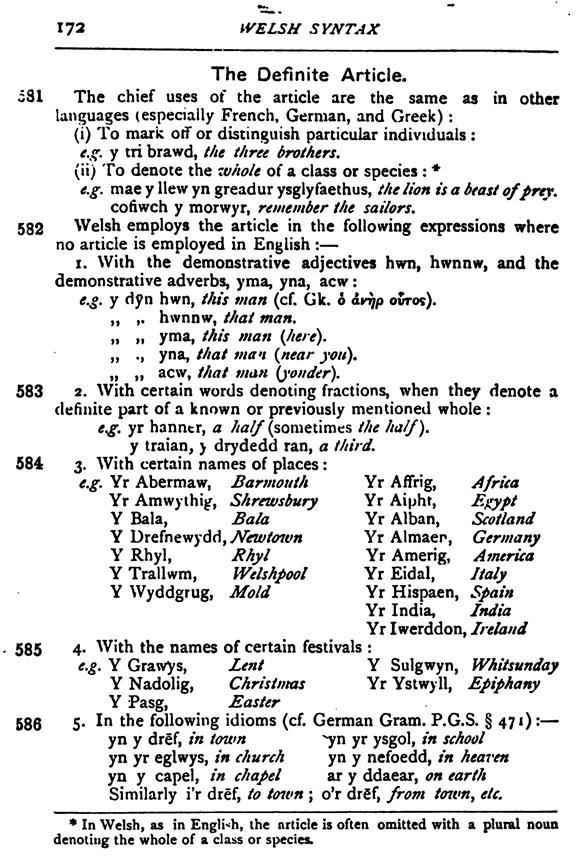

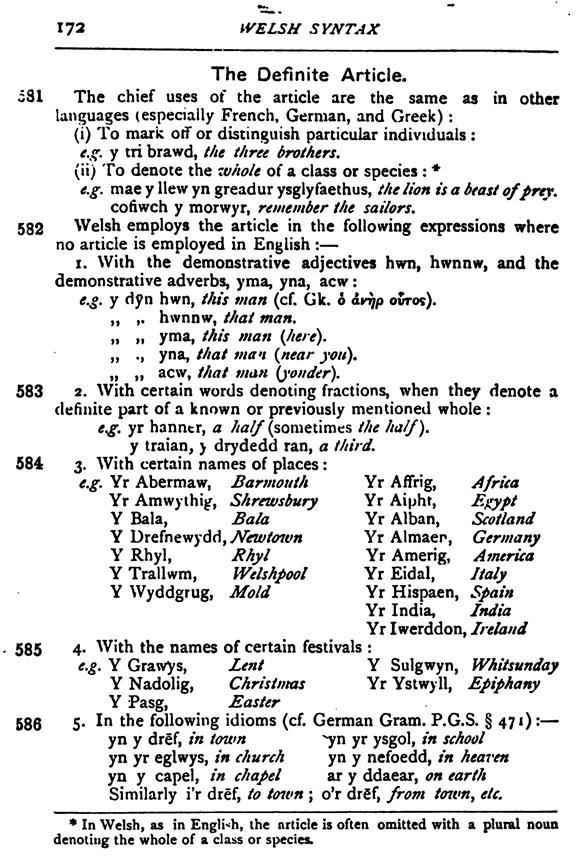

·····

Y-Diphthongs

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

ỳi (In North Wales only)

einioes

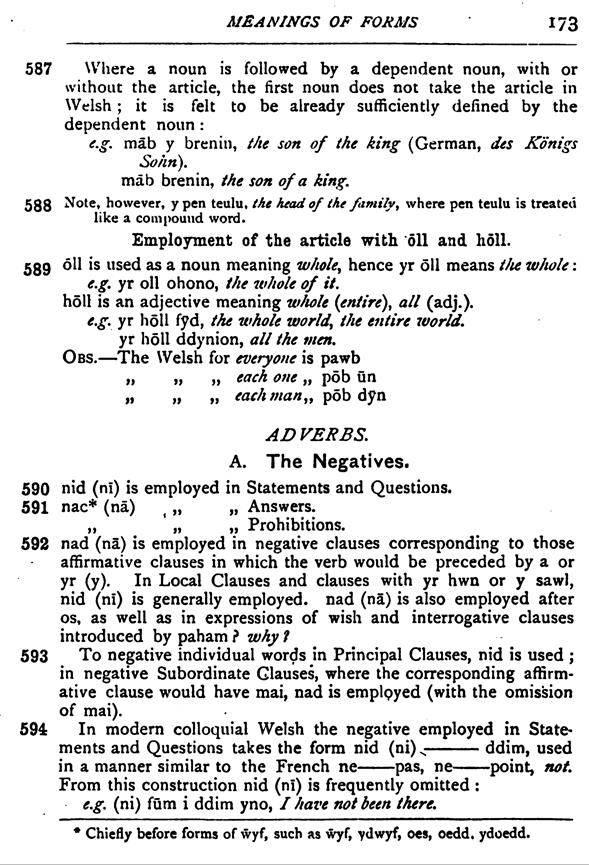

ỳu (In North Wales only)

gweunydd

ỳw

bywyd

NOTE. - yw is not infrequently pronounced as ow; e.g. Howel for Hywel

·····

OBS. Rules for determining the quantity of a vowel or a diphthong are given

in the Appendix

N.B. -In the sequel, the quantity of only long vowels and diphthongs will be

indicated, where necessary, thus: - tâd, mâe, â. Short vowels and diphthongs

will be left unmarked.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7189) (tudalen 006)

|

WELSH

GRAMMAR

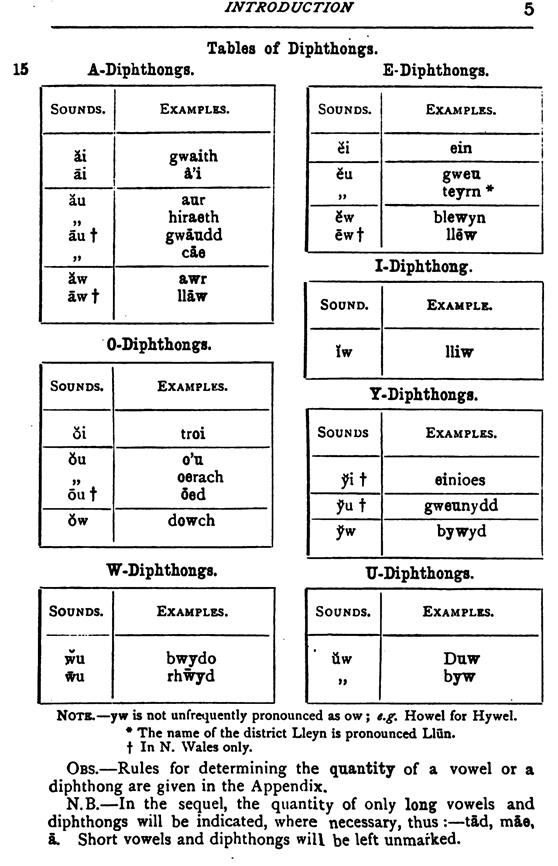

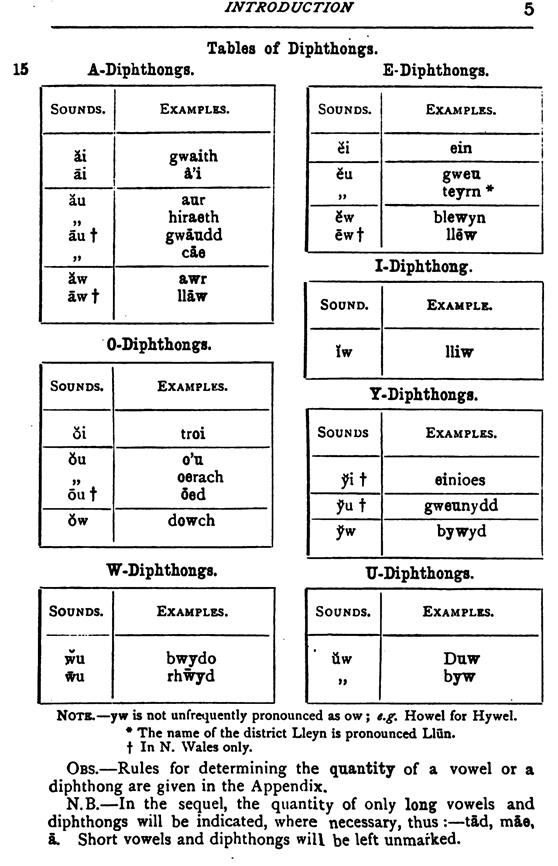

Further Classification of Consonants. I ConionaiLt Saimda majr also ba

classed as: —

I. Voiced, i.e. Accompanied by vibration of the edgfs of the vocai chords.

t. Voiceless, i.e. Not accompanied by vibration of the edges of the vocal

chords. Contrast the sound b (voiced) with the sound p (voiceless). f Or

again as: —

1. HComeiitary, i.e. fonned by a kind of explosion, when the breath is again

set free after a momentary closure of the mouth. During this momenUry closure

there is a very brief interval of silence; hence their common name, ' mutes

'; e.g. b, p, d, t, %, o.

2, Continuotts, i.t. formed by a stream of air rubbing against a narrow

passage of the mouth. The continuous sounds represented in Welsh by i, w, f ,

ff (pt), dd, th, ch, t, are generally called ' spirants.' The continuous

sounds represented by 1, 11; r, rh; m, mh; n, nh; ng, ngli, are generally

called ' liquids,' but II, rh, mil, nli, ngh have also a marked resemblance

to the spirants.

Classified Table of Consonants.

Labials.

Labio-dentals.

Dentals.

Palatals.

Gutturals.

Voiceless Voiced

byd

tad dyn

Pnlatal.

Vilar.

ces

Calh gwr

ii

Voiceless Voiced

gwyn

phen, ffydd fyd .

thad, sel Sib

ddyn

eisio iaith

Chath

Voiceless* Voiced

mien myd

nhad' nyn

unionf?)

nghath ng*r

J

Voiceless* Voiced

Haw, rhaw law, raw

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7190) (tudalen 007)

|

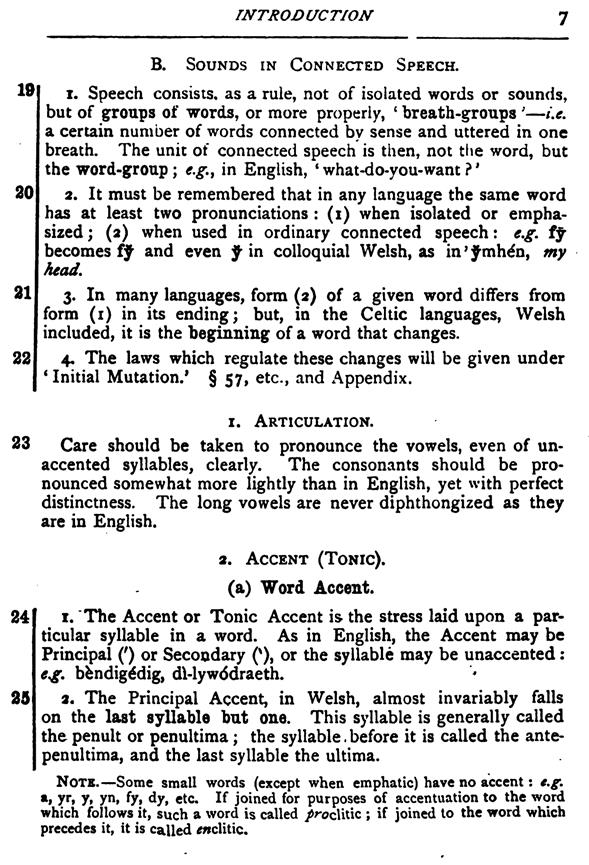

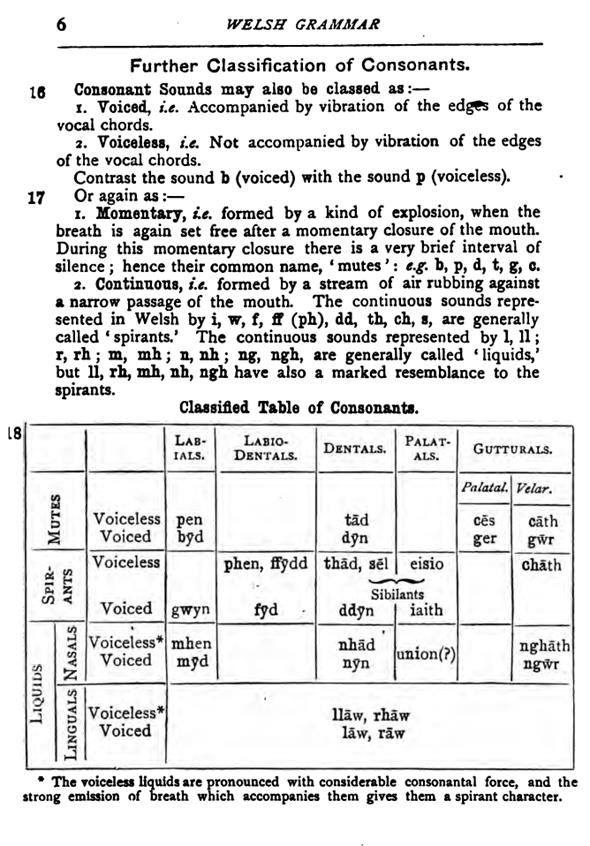

7

INTRODUCTION

19

20

21

22

B. Sounds in Connected Speech.

1. Speech consists, as a rule, not of isolated words or sounds, but of groups

of words, or more properly, * breath-groups ' — i.e. a certain number of words connected bv

sense and uttered in one breath. The unit of connected speech is then, not

the word, but the word-group; e.g, in English, * what-do-you-want? '

2. It must be remembered that in any language the same word has at least two

pronunciations: (x) when isolated or emphasized; (2) when used in ordinary

connected speech: e,g, fy becomes fy and even y in colloquial Welsh, as in '

ymhn, my head,

3. In many languages, form (2) of a given word differs from form (i) in its

ending; but, in the Celtic languages, Welsh included, it is the beginning of

a word that changes.

4. The laws which regulate these changes will be given under * Initial

Mutation.' § 57, etc., and Appendix.

23

24

25

1. ARTICULATION

23 Care should be taken to pronounce the vowels, even

of unaccented syllables, clearly. The consonants should be pronounced

somewhat more lightly than in English, yet with perfect distinctness. The

long vowels are never diphthongized as they are in English.

2. ACCENT (TONIC)

(a) Word Accent

24 1. The Accent or Tonic

Accent is the stress laid upon a particular syllable in a word. As in

English, the Accent may be Principal ( ´ ) or Secondary ( ` ), or the

syllable may be unaccented: e.g. bèndigédig, dì-lywódraeth.

{NODIAD: bendigedig = wonderful, dilywodraeth = ungoverned, uncontrolled}

25 1. The Principal

Accent, in Welsh, almost invariably falls on the last syllable but one. This syllable is generally

called the penult or penultima; the syllable before it is called the

antepenultima, and the last syllable the ultima.

NOTE. - Some small words (except when emphatic) have no accent: e.g. a, yr,

y, yn, fy, dy, etc. If joined for purposes of accentuation to the word which

follows it, such a word is called proclitic;

if joined to the words which precedes it, it is called enclitic.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7191) (tudalen 008)

|

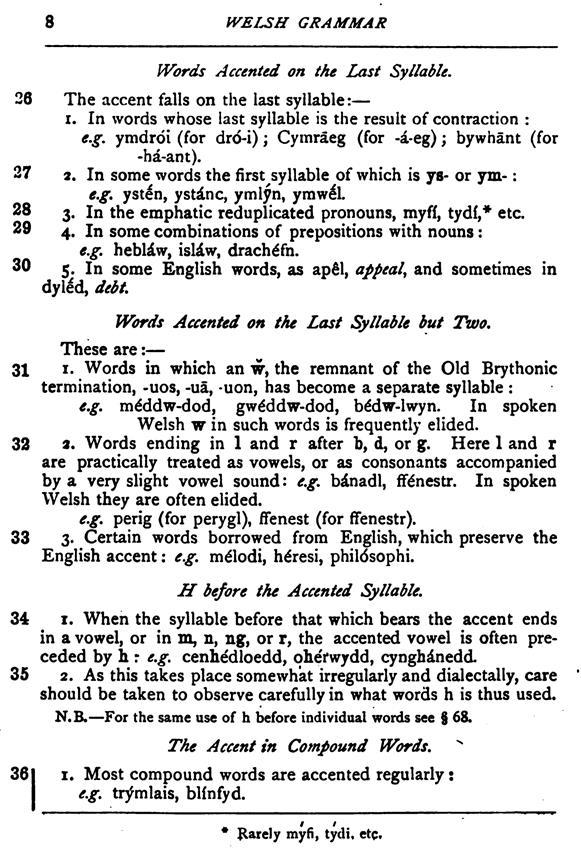

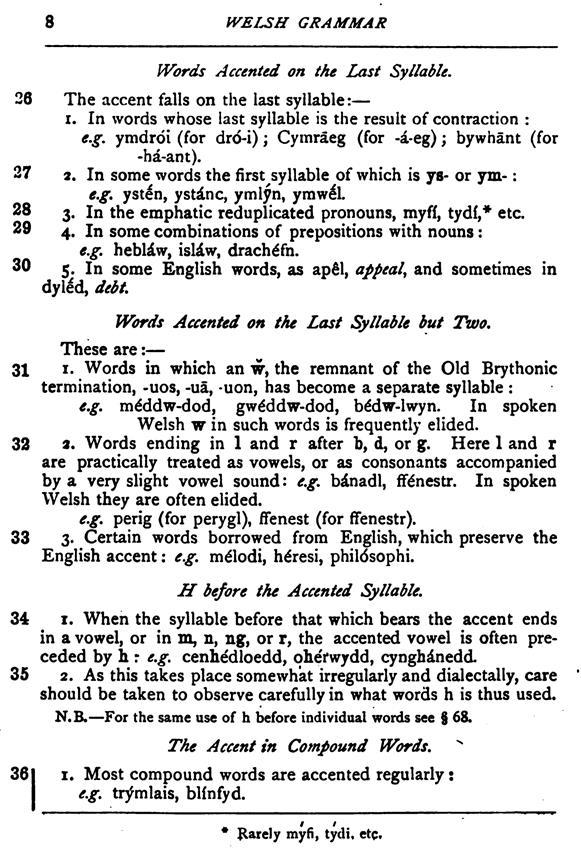

8 WELSH GRAMMAR Words Accented on the Last Syllable

26 The accent falls on the last syllable: -

.....1. In words whose last syllable is the result of contraction:

..........e.g. ymdrói (for dró-i); Cymrâeg (for -á-eg); bywhânt (for há-ant).

{NODIAD: ystên = pitcher, ystánc = stake, ymlŷn = it sticks itself, it

binds itself, ymwêl = he / she visits}

27 2. In some words the

first syllable of which is ys- or ym-:

..........e.g. ystên, ystánc, ymlŷn, ymwêl

{NODIAD: ymdrói = turn, rotate; Cymrâeg = Welsh language; bywhânt = they eat}

28 3. In the emphatic

reduplicated pronouns, myfí, tydí, etc.*

*(Rarely my´fi, ty´di, etc)

{NODIAD: myfi = I, tydi = you}

29 4. In some

combinations of prepositions with nouns:

..........e.g. hebláw, isláw, drachéfn.

{NODIAD: hebláw = besides, isláw = below, drachéfn = again}

30 5. In some English

words, as apêl, appeal,

and somtiems in dylêd, debt

Words Accented on the Last Syllable but Two

These are:-

31 1. Words in which an

w`, the remnant of the Old Brythonic termination, -uos, -uâ, -uon, has become

a separate syllable:

..........e.g. méddw-dod, gwéddw-dod, bédw-lwyn. In

spoken Welsh w in such words is frequently elided.

{NODIAD: meddwdod = drunkenness, gweddwdod = widowhood, bedwlwÿn = birch

grove}

32 2. Words ending in l and r after b, d, or g. Here l and r are practically treated as

vowels, or as consonants accompanied by a very slight vowel sound: e.g.

bánadl, ffénestr. In spoken Welsh they are often elided.

..........e.g. perig (for perygl), ffenest (for ffenestr).

{NODIAD: banadl = broom bushes, broom as a material, ffenestr = window;

perÿgl = danger}

33 3. Certain words

borrowed from English, which preserve the English accent: e.g. mélodi,

héresi, philósophi.

{NODIAD: mélodi = melody, héresi = heresy, philósophi = philosophy}

H before the Accented Syllable.

34 1. When the syllable

before that which bears the accent ends i a vowel, or in m, n, ng, or r, the accented vowel is

often preceded by h:

e.g. cenhédloedd, oherwydd, cynghánedd.

{NODIAD: cenedl = nation, cenhedloedd = nations; oherwÿdd = because,

cynghanedd = alliteration}

35 2. As this takes

place somewhat irregularly and dialectally, care should be taken to observe

carefully in what words h is thus used.

.........N.B. - For the same use of h before individual words see @68.

The Accent in Compound Words.

36 1. Most compound

words are accented regularly:

.........e.g. try´mlais, blínfyd.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7192) (tudalen 009)

|

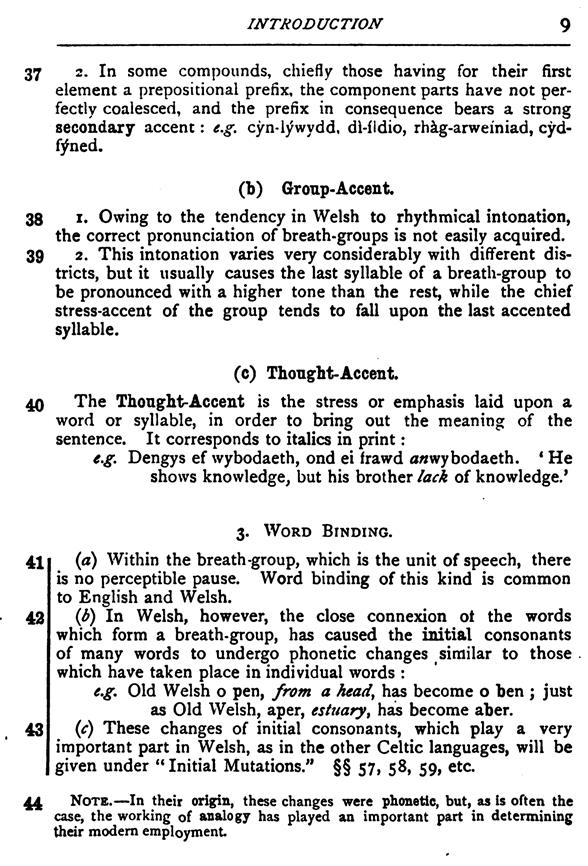

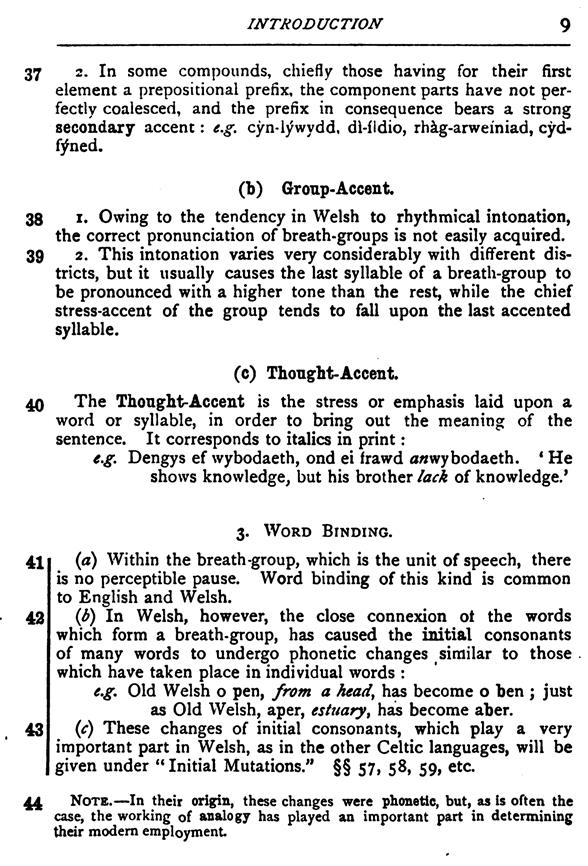

9 INTRODUCTION

37 2. In some compounds, chielfy those having for their

first element a prepositional prefix, the component parts have not perfectly

coalesced, and the prefix in consequence bears a strong secondary: e.g. cy`n-lýwydd, dì-fídio,

rhàg-arwéiniad, cy`d-fýned.

(b) Group-Accent

38 1. Owing to the tendency

in Welsh to rhythmical intonation, the correct pronuncaition of breath-groups

is not easily acqured.

39 2. This intonation varies

very considerably with different districts, but it usually causes the last

syllable of a breath-group to be pronounced with a higher tone than the rest,

while the chief stress-accent of the group tends to fall upon the last

accented syllable.

(b) Thought-Accent

40 1. The Thought-Accent is the stress or emphasis laid

upon a word or syllable, in order to bring out the meaning of the sentence.

In corresponds to italics in print:

e.g. Dengys ef wybodaeth, ond ei frawd anwybodaeth.

‘He shows knowledge, but his brother lack of knowledge’.

3. WORD BINDING

41 (a) Within the

breath-group which is the unit of speech, there is no perceptible pause. Word

binding of this kind is common to English and Welsh.

42 (b) In Welsh,

however, the close connexion of the words which form a breath group, has

caused the initial consonants of many words to undergo phonetic changes

similar to those which have taken place in individual words:

e.g. Old Welsh o pen, from a head, has become o ben; just as Old Welsh aper, estuary, has become aber.

43 (c) These changes of

initial consonants, which play a very important part in Welsh, as in the

other Celtic languages, will be given under “Initial Mutations.” @@57, 58,

59, etc.

44 NOTE. - In their origin, these changes were phonetic, but, as is often

the case, the working of analogy has played an importnat part in

determining their modern employment.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7193) (tudalen 010)

|

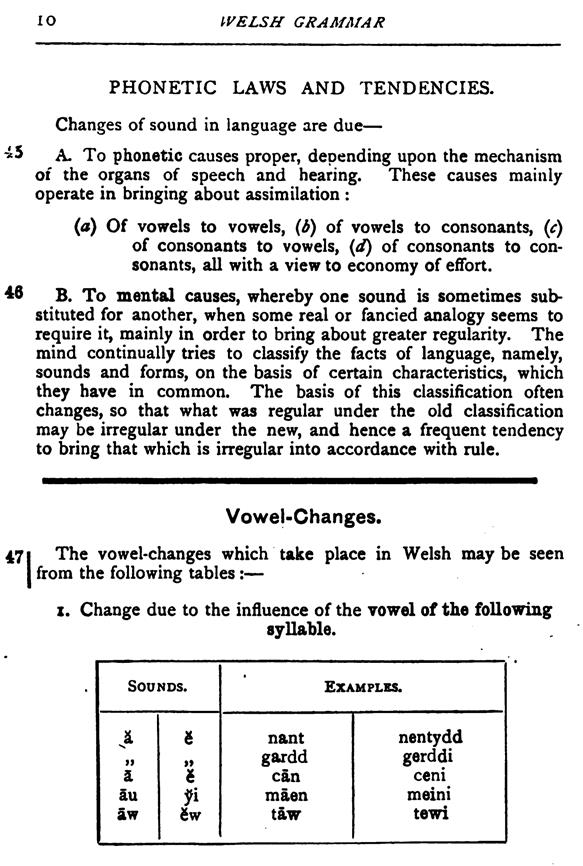

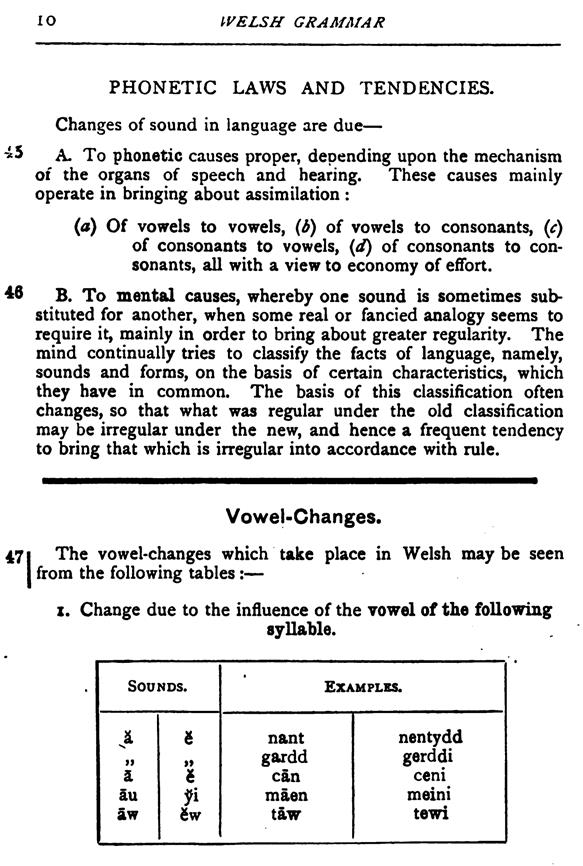

10 WELSH GRAMMAR

PHONETIC LAWS AND TENDENCIES.

Changes of sound in language are due —

*«5 A To phonetic causes proper, depending upon the mechanism of the organs

of speech and hearing. These causes mainly operate in bringing about

assimilation:

(a) Of vowels to vowels, (b) of vowels to consonants, () of consonants to

vowels, (d) of consonants to consonants, all with a view to economy of

effort.

0 B. To mental causes, whereby one sound is sometimes substituted for

another, when some real or fancied analogy seems to require it, mainly in

order to bring about greater regularity. The mind continually tries to

classify the facts of language, namely, sounds and forms, on the basis of

certain characteristics, which they have in common. The basis of this

classification often changes, so that what was regular under the old

classification may be irregular under the new, and hence a frequent tendency

to bring that which is irregular into accordance with rule.

Vowel-Changes.

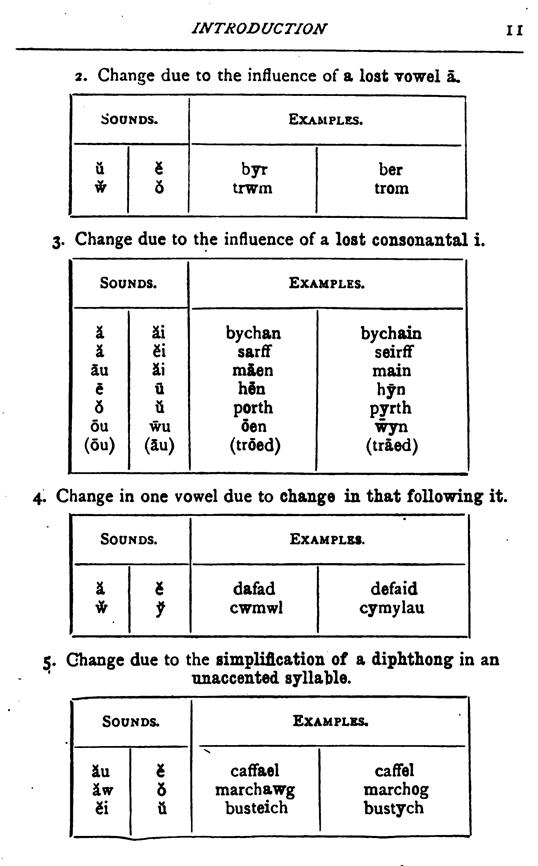

47 1 The vowel-changes which take place in Welsh may be seen I from the

following tables: —

z. Change due to the influence of the vowel of the following

syllable.

Sounds.

t

Examples.

au aw

nant

gardd

can

maen

taw

nentydd gerddi

ceni meini

tewi

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7194) (tudalen 011)

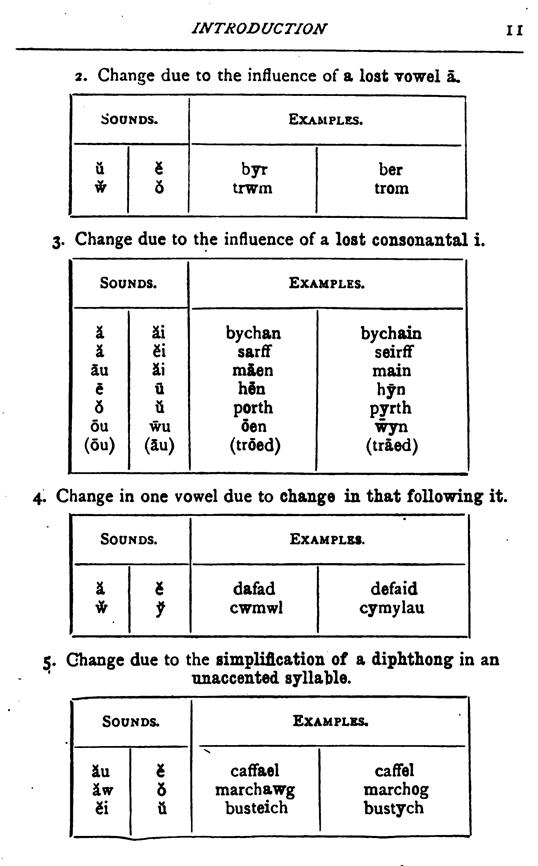

|

INTRODUCTION

EXAMPLES

à

à

âu

ê

ò

ôu

(ôu)

ài

èi

ài

û

ù

wû

(âu)

bychan

sarff

mâen

hên

porth

ôen

(trôed)

bychain

seirff

main

hŷn

pyrth

ŵyn

(trâed)

{NODIAD: bychan, plural: bychain = small; sarff, plural: seriff = serpent;

maen, plural: main = stones; hen = old, hŷn = older; porth, plural:

pyrth = gateway; oen, plural: wyn = lamb; troed, plural: traed = foot)

4. change in one vowel due to change in that following it

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

à

w`

ài

y

dafad

cwmwl

defaid

cymylau

{NODIAD: dafad, plural: defaid = sheep; cwmwl, plural: cymylau = cloud)

5. change due to the simplificarion of a diphthong in an unaccented syllable

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

àu

àw

èi

è

ò

ù

caffael

marchawg

busteich

caffel

marchog

bustych

{NODIAD: caffael (old form/ caffel = to get; marchawg (old form) / marchog =

knight; busteich, bustÿch = two plural forms of bustach = bullock)

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7195) (tudalen 012)

|

12 WELSH GRAMMAR

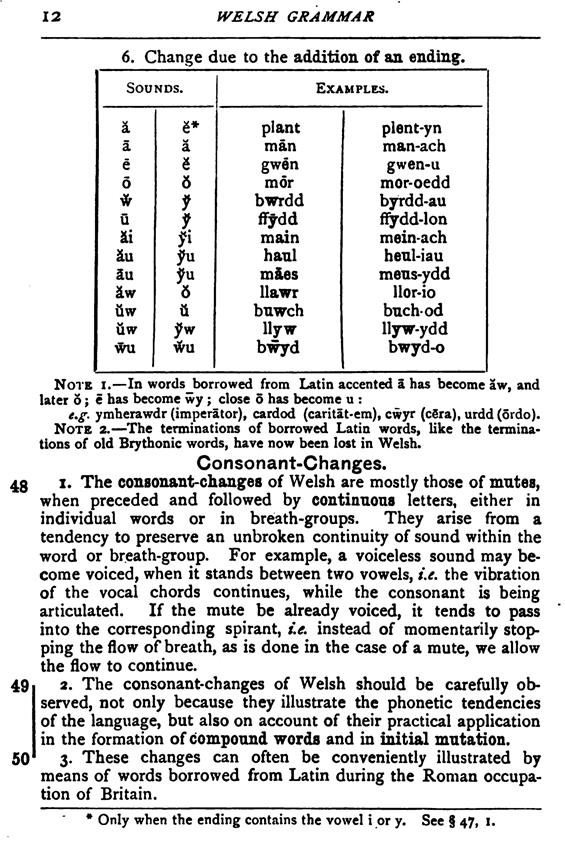

2. change due to the influence of a lost vowel â

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

ù

w`

è

ò

byr

trwm

ber

trom

{NODIAD: byr = short, trwm = heavy; ber = feminine form of byr; trom =

feminine form of trwm }

3. change due to the influence of a lost consonantal i

SOUNDS

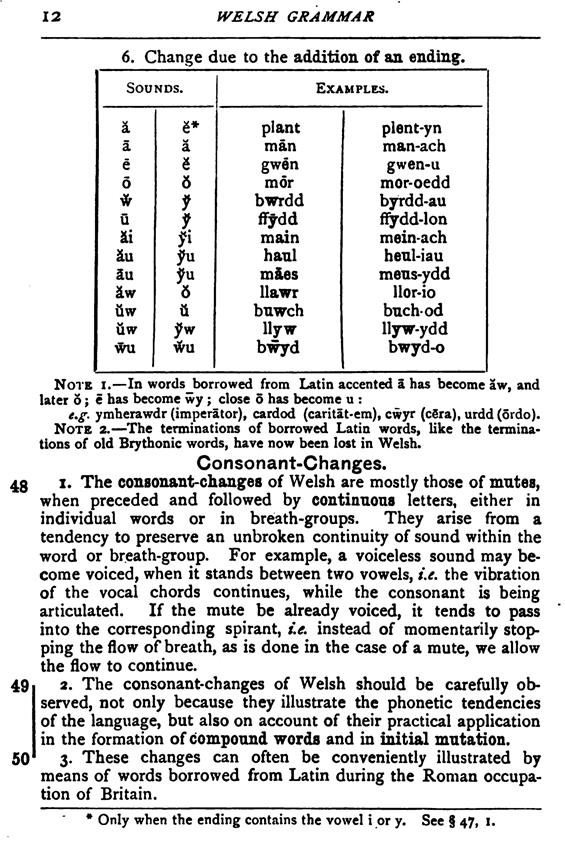

6. change due to the addition of an ending

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

à

â

ê

ô

w

`u

ài

àu

âu

àw

ùw

ùw

wû

è*

ò

è

ò

y

`y

y`i

y`u

y`u

ò

ù

y`w

wù

plant

mân

gwên

môr

bwrdd

ffŷdd

main

haul

mâes

llawr

buwch

llyw

bŵyd

plent-yn

man-ach

gwen-u

mor-oedd

byrdd-au

ffydd-lon

mein-ach

heul-iau

meus-ydd

llor-io

buch-od

llyw-ydd

bwyd-o

*(only when the ending contains the vowel i or y). See @47.1

NOTE 1. - In words borrowed from Latin accented â has become àw, and later ô;

ê has become ŵy: close ô has become u:

e.g. ymherawdr (imperâtor), cardod (caritât-em), cŵyr (cêra), urdd

(ôrdo).

NOTE 2. - The terminationof borrowed Latin words, like the termination of old

Brythonic words, have now been lost in Welsh.

{NODIAD: plant = children, plent-yn = child, mân = small, man-ach = smaller,

gwên = a smile, gwen-u = to smile, môr = sea, mor-oedd = seas, bwrdd = table,

byrdd-au = tables, ffŷdd = faith, ffydd-lon = faithful, main = slim,

mein-ach = slimmer, haul = sun, heul-iau = suns, mâes = field, meus-ydd =

fields, llawr = floor, llor-io to floor (somebody), buwch = cow, buch-od =

cows, llyw = helm, llyw-ydd = leader, bŵyd = food, bwyd-o = feed)

Consonant-Changes

48 1. The consonant-changes of Welsh are mostly of mutes, when preceded and

followed by continuous letters, either in individual words or in

breath-groups. They arise from a tendency to preserve an unbroken continuity

of sound within the word or breath-ggroup. Fro example, a voiceless sound may

become voiced, when it stands between two vowels, i.e. the vibration of the

vocal chords continues, while the consonant is being articulated. If the mute

be already voiced, it tends to pass into the corresponding spirant, i.e.

instead of momentarily stopping the flow of breath, as is done in the case of

a mute, we allow the flow to continue.

49 2. The consonant-changes of Welsh should be carefully observed, not only

because they illustrate the phonetic tendencies of the language, but also on

account of their practical application in the formation of compound words and

in initial mutation.

50 3. These changes can often be conveniently illustrated by means of words

borrowed from Latin during the Roman occupation of Britain.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7196) (tudalen 013)

|

13 INTRODUCTION

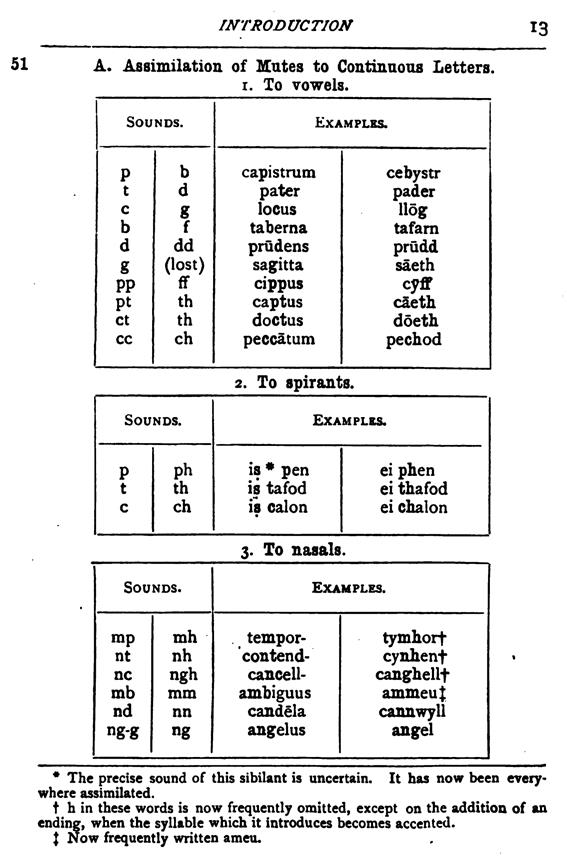

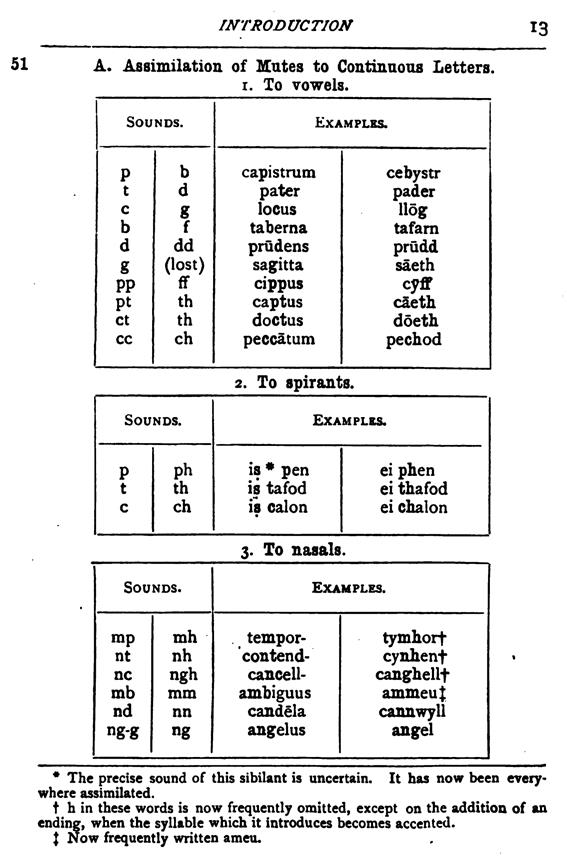

:51 A. Assimilation of Mutes to Continuous Letters. 1. To vowels.

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

p

t

c

b

d

g

pp

pt

ct

cc

b

d

g

f

dd

(lost)

ff

th

th

ch

capistrum

pater

locus

taberna

prûdens

sagitta

cippus

captus

doctus

peccâtum

cebystr

pader

llôg

tafarn

prûdd

sâeth

cŷff

câeth

dôeth

pechod

·····

{NODIAD: cebystr = halter, pader = Lord’s Prayer, padernoster, llôg =

interest, tafarn = tavern, prûdd = gloomy, sâeth = arrow, cŷff = tree

stump, câeth = slave; enslaved, addicted, dôeth = wise, pechod = sin }

2. To spirants

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

p

t

c

ph

th

ch

is *pen

is tafod

is calon

ei phen

ei thafod

ei chalon

*The precise sound of this sibilant is uncertain. It has now been everywhere

assimilated

{NODIAD: ei phen = her head, ei thafod = her tongue, ei chalon = her heart }

·····

3. To nasals

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

mp

nt

nc

mb

nd

ng-g

mh

nh

ngh

mm

nn

ng

tempor-

contend-

cancell-

ambiguus

candêla

angelus

tymhor*

cynhen*

canghell*

ammeu**

cannwyll

angel

*h in these words is now fequently opmitted, except on the addition of an

ending, when the syllable which it introduces becomes accented

**Now frequently written ameu {NODIAD: Now amau}

{NODIAD: tymhor- (penult form of tymor = season), cynhen- (penult form of

cynne = contention, dispute), canghell- (as in canghellor = chancellor),

ammeu (now amau, = to doubt), cannwyll = candle, angel = angle}

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7197) (tudalen 014)

|

WELSH GRAMMAR 14

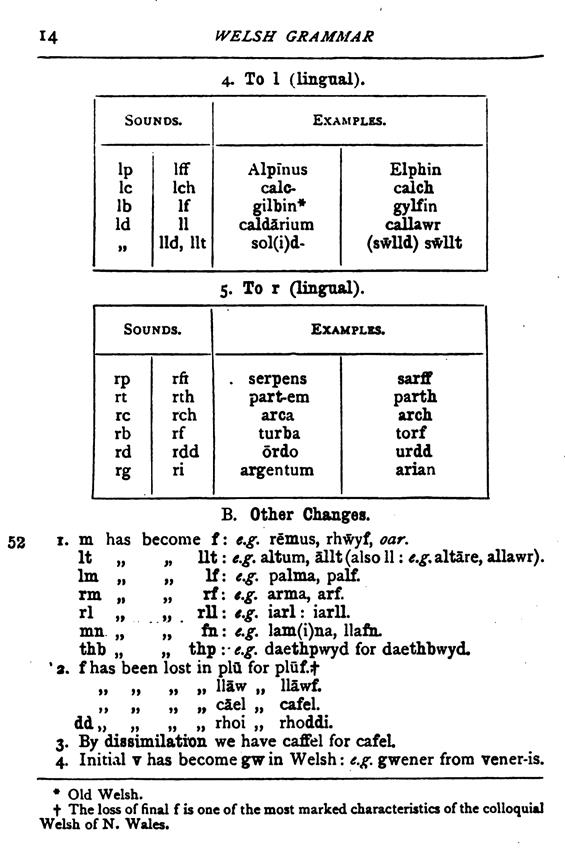

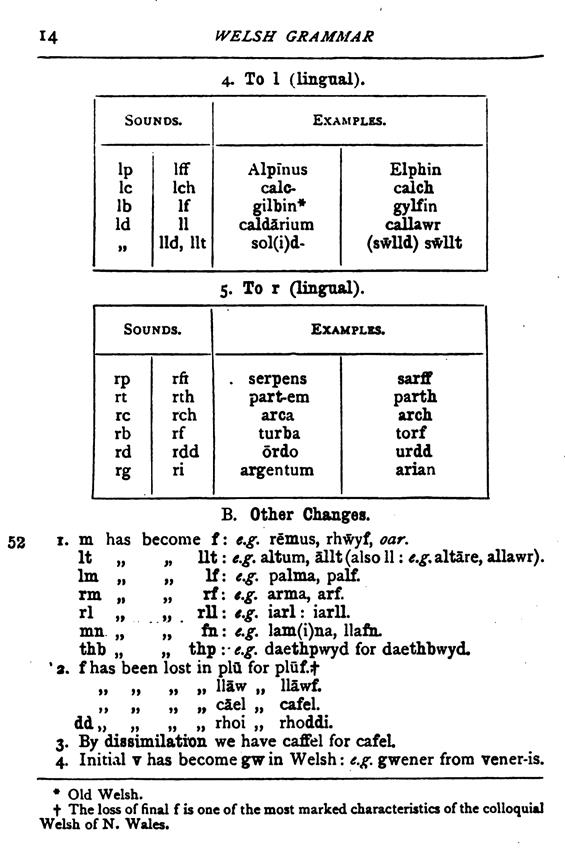

4. To l (lingual)

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

lp

lc

lb

ld

ld

lff

lch

lf

ll

lld, llt

Alpinus

calc-

gilbin (Old Welsh)

caldârium

sol(i)d-

Elphin

calch

gylfin

callawr

(sŵlld) sŵllt

{NODIAD: tymhor- (Elphin (modern spelling Elffin; nowadays obsolete, replaced

by Alpau), calch = lime, gylfin = beak, callawr = cauldron, swllt = shilling}

····

5. To r (lingual)

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

rp

rt

rc

rb

rd

rg

rft

rth

rch

rf

rdd

ri

serpens

part-em

arca

turba

ôrdo

argentum

sarff

parth

arch

torf

urdd

arian

{NODIAD: sarff = serpent, parth = part, district, arch = coffin, torf =

crowd, urdd = religious order, arian = silver}

B. Other Changes

52 1. m has become f: e.g. rêmus, rhŵyf, oar

··········lt has become llt: e.g. altum, âllt (also ll: e.g. altâre, allawr)

··········lm has become lf: e.g. palma, palf

··········rm has become rf: e.g. arma, arf

··········rl has become rll: e.g. iarl, iarll

··········mn has become rdd: e.g. lam(i)na, llafn

··········thb has become thp: e.g. daethpwyd for daethbwyd

{NODIAD: rhŵyf = oar, llat = hill, allawr (now allaor) = altar, palf =

palm of the hand, arf = arm, weapon, iarll = earl, llafn = blade, daethpwyd =

it has been brought}

2. f has been lost in plû for plûf*

f has been lost in llâw for llâwf

f has been lost in câel for cafel

dd has been lost in rhoi for rhoddi

*The loss of final f is one of the most marked characteristics of the

colloquial Welsh of N. Wales.

{NODIAD: plu= feather, llaw = handcael = get, receive, rhoi = give}

3. By dissimilation we have caffel for cafel

{NODIAD: caffel = (old form) (v) get, receive, (n) acquisition}

4. Initial v has become gw in Welsh e.g. gwener from vener-is

{NODIAD: Gwener = Venus, Friday}

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7198) (tudalen 015)

|

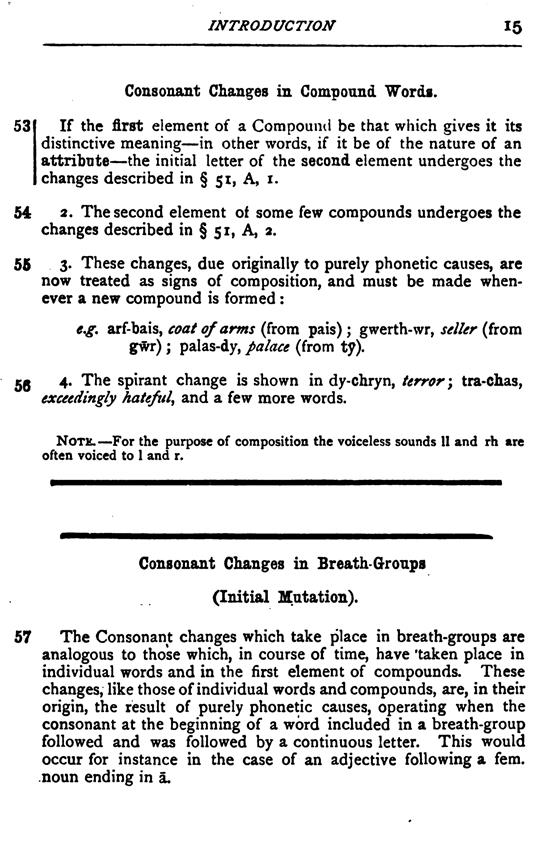

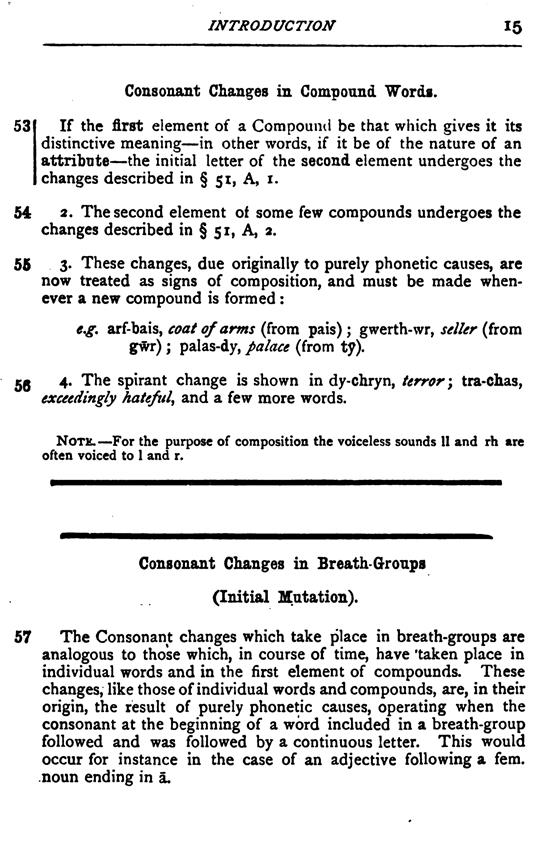

INTRODUCTION 15

Consonant

Changes i Compound Words

53 1. If the first element of a Compound be that which

gives it its distinctive meaning - in other words, if it be of the nature of

an attribute - the initial letter of the second element undergoes the changes

described in @51, A, 1.

54 2. The second element

of a some few compounds undergoes the changes described in @51, A, 2.

55 3. These changes, due

originally to phonetic causes, are now treated as signs of composition, and

mustbe made whenever a new compound is formed:

e.g. arf-bais, coat

of arms (from pais)

gwerth-wr, seller, from gŵr

palas-dy, palace, from tŷ

{NODIAD: pais = petticoat, gŵr = man, tŷ = house}

56 4. The spirant change

is hown in dy-chryn, terror;

tra-chas, exceedingly

hateful, and a few more words.

NOTE:- For the purpose of compostion the voiceless sounds ll and rh are often

voiced to l and r.

Consonant Changes in Breath-Groups

(Initial Mutation)

57 The Consonant changes which

take place in breath groups are analogous to those, which, in course of time,

have taken place in individual words and in the first elelment of compounds.

These changes, like those of individual words and compounds, are, in their

origin, the result of purely phonetic causes, operating when the consonant at

the beginning of a word included in a breath-group followed and was follwed

by a continuous letter. This would occur for instance in the case of an

adjective following a fem. noun ending in â.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7199) (tudalen 016)

|

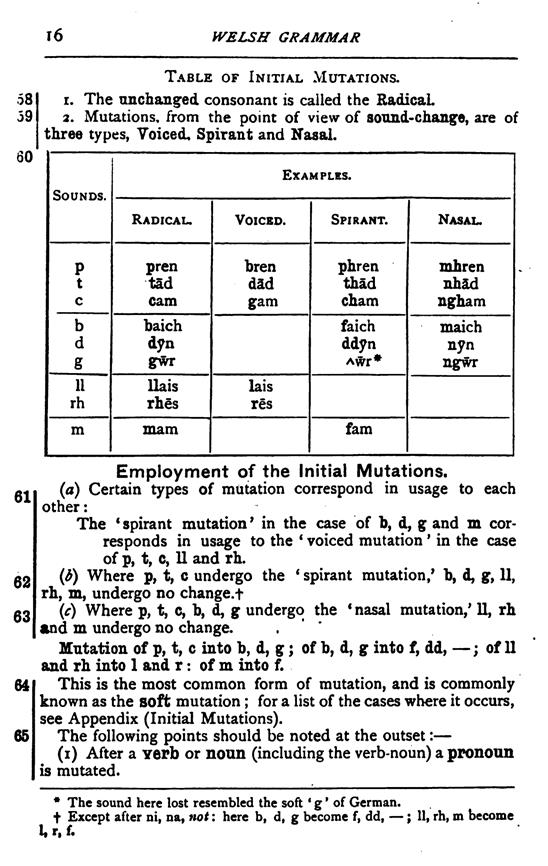

i6 WELSH GRAMMAR

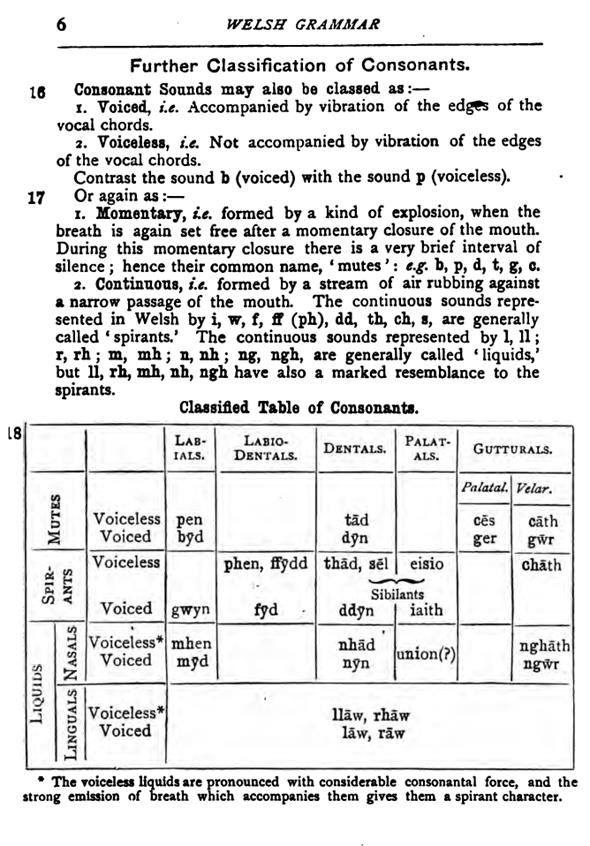

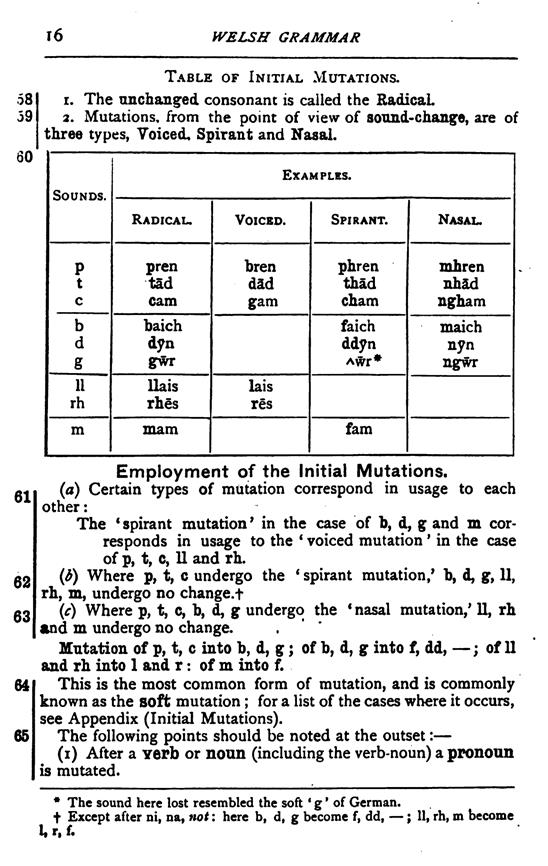

TABLE OF INTIAL MUTATIONS

58 1. The unchanged consonant is called the Radical

59 2. Mutations, from the point of view of sound-change, are of three types,

Voiced, Spirant and Nasal.

60

SOUNDS

EXAMPLES

RADICAL

VOICED

SPIRANT

NASAL

p

t

c

pren

tâd

cam

bren

dâd

gam

phren

thâd

cham

mhren

nhâd

ngham

b

d

g

baich

dŷn

gŵr

faich

ddŷn

#ŵr*

maich

nŷn

ngŵr

ll

rh

llais

rhes

lais

res

m

mam

fam

*The sound here lost resembled the soft ‘g’ of German

{NODIAD: pren = tree, tad = father, cam = step, baich = load, burden, dyn =

man, gwr = man or husband, llais = voice, rhes = row (of houses, etc), mam =

mother}

Employment of the Initial Mutations

61 (a) Certain types of mutation correspond i usage to each other:

The ‘spirant mutation’ in the case of b, d, g and m corresponds in usage to

the ‘voiced mutation’ in the case of p, t, c, ll and rh.

(b) Where p, t, c undergo the ‘spirant mutation,’ b, d, g, ll, rh, m undergo

no change.

(Except after ni, na, not; here

b, d, g become f, dd, #;

ll, rh, m become l, r, f)

(c) Where p, t, c, b, d, g undergo the ‘nasal mutation,’ ll, rh, m undergo no

change.

Mutation

of p, t, c, into b, d, g

of b, d, g into f, dd, #

of ll and rh into l and r

of m into f

64 This is the most common form of mutation, and is commonly known as the

soft mutation; for a list of the cases where it occurs, see Appendix (Initial

Mutations).

69 The following points should be noted at the outset:-

(1) After a verb or noun (including the verb-noun) a pronoun is mutated.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7200) (tudalen 017)

|

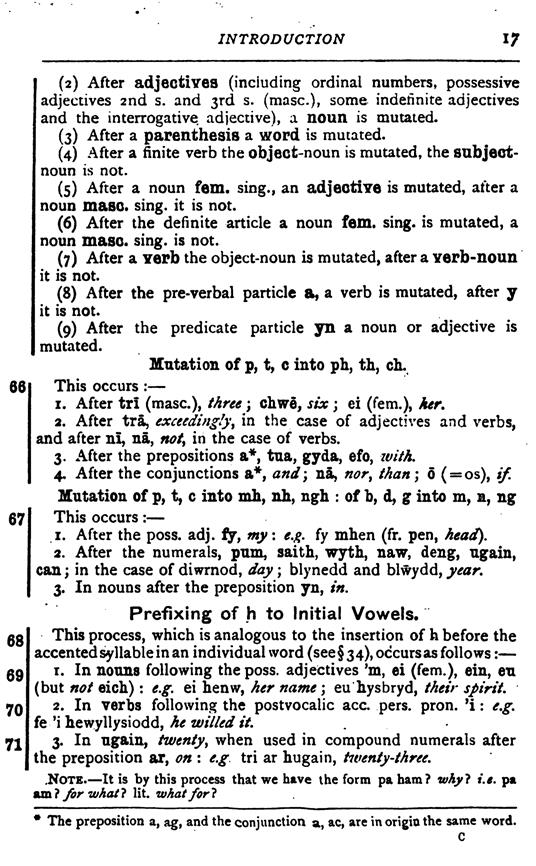

INTRODUCTION

17

66

67

68 69 70 71

(2) After adjeotives (including ordinal numbers, possessive adjectives 2nd s.

and 3rd s. (masc), some indefinite adjectives and the interrogative

adjective), a noun is mutated.

(3) After a parenthesis a word is mutated.

(4) After a finite verb the object-noun is mutated, the subject-noun is not.

(5) After a noun fem. sing., an adjective is mutated, after a noun masc*

sing, it is not.

(6) After the definite article a noun fem. sing, is mutated, a noun masc.

sing, is not.

(7) After a Verb the object-noun is mutated, after a verb-noun it is not.

(8) After the pre-verbal particle a, a verb is mutated, after y it is not.

(9) After the predicate particle yn a noun or adjective is mutated.

Mutation of p, t, c into ph, th, ch.

This occurs: —

1. After tri (masc), t/iree; chwe six; ei (fem.), Aer.

2. After tra, exceedingly in the case of adjectives and verbs, and after ni,

na, not in the case of verbs.

3. After the prepositions a*, tua, gyda, efo, ivith,

4. After the conjunctions a*, and-y na, nor than] 6 ( = os), if.

Mutation of p, t, c into mh, nh, ngh: of h, d, g into m, n, ng

This occurs: —

1. After the poss. adj. fy, my: e., fy mhen (fr. pen, head).

2. After the numerals, pum, saith, wyth, naw, deng, ugain, can; in the case

of diwrnod, day; blynedd and blwydd, year,

3. In nouns after the preposition yn, in.

Prefixing of h to Initial Vowels.

This process, which is analogous to the insertion of h before the accented

syllable in an individual word (see § 34), occurs as follows: —

T. In nouns following the poss. adjectives 'm, ei (fem.), ein, eu (but not

eich): e.g. ei henw, her name; eu hysbryd, their spirit.

2. In verbs following the postvocalic ace. pers. pron. 'i: e,g. fe

'ihtwyWysioddy he wi//ed it.

3. In ugain, twenty, when used in compound numerals after the preposition ar,

on: e.g tri ar hugain, tiventy-three.

.Note. — It is by this process that we have the form pa ham? why'i i.e. pa

tja} for what} lit. what for}

• The preposition a, ag, and the conjunction a, ac, are in origin the same

word.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7201) (tudalen 018)

|

18 WELSH

GRAMMAR

ACCIDENCE.

Accidence is the part of grammar which tells how words are declined (nouns,

adjectives, pronouns), compared (adjectives), or conjugated (verbs).

73 Declension of nouns and adjectives in Welsh is limited to the formation of

Singulars (in the case of nouns only). Plurals and Feminines.

To some prepositions pronominal suffixes are added.

Obs. — The Definite Article, yr, y, will be found under " Demonstrative

Adjectives," § 145.

Caution. — In parsing, each word should be parsed separately.

NOUNS AND ADJECTIVES.

74 I. Welsh nouns and adjectives have two Numbers — the Singular and the

Plural — but no Case-endings.

2. The relations conveyed in Latin, and at one time in Welsh, by the Genitive,

are now mainly expressed by putting the noun (uninflected) immediately after

the noun on which it depends.

3. Other relations conveyed by the Genitive, as well as those conveyed by the

Dative or Ablative, are expressed by using a preposition. The Nominative and

Accusative are alike in form.

Obs. — The adjective generally follows the noun in Welsh. See Syntax, §337.

N.B. — Note carefully under pronouns, verbs and prepositions the use made of

the noun in supplementing the pronominal, verbal and prepositional forms.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7202) (tudalen 019)

|

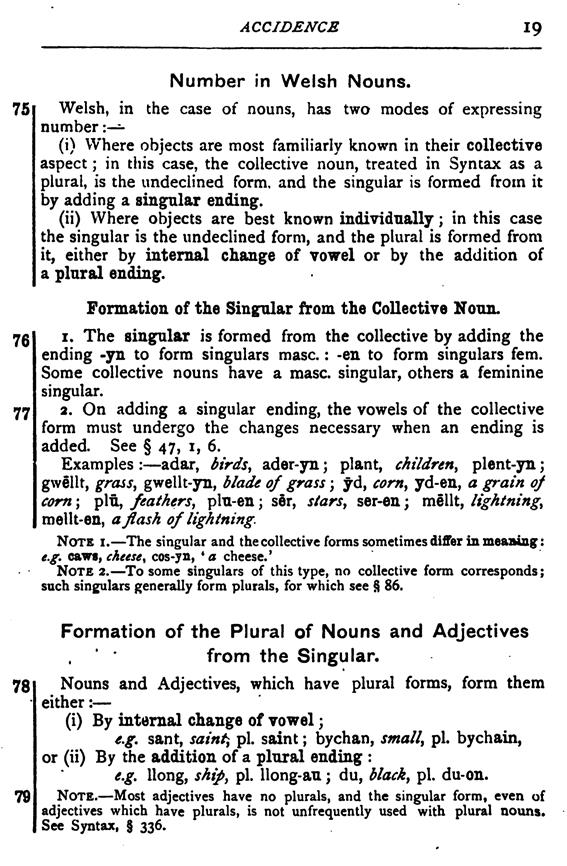

19 ACCIDENCE

Number in Welsh Nouns.

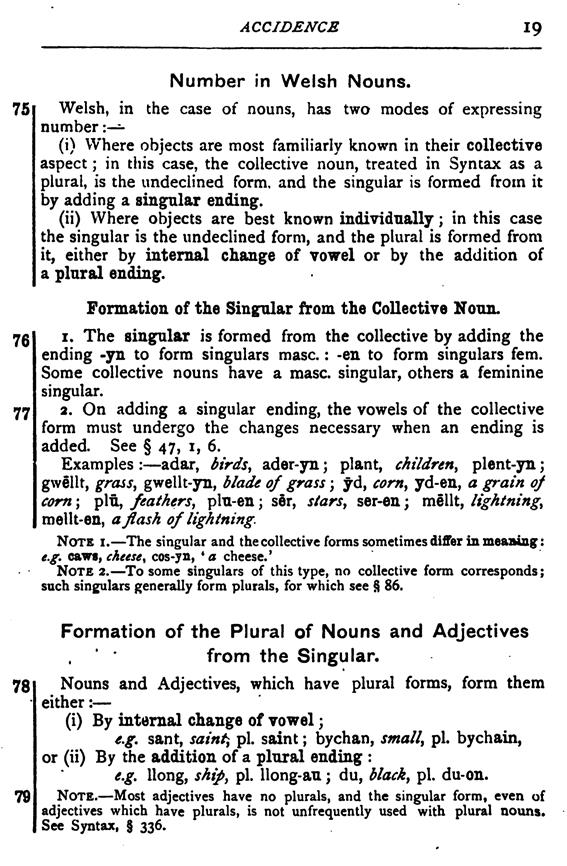

75 Welsh, in the case of nouns, has two modes of expressing number:—

(i) Where objects are most familiarly known in their collective aspect; in

this case, the collective noun, treated in Syntax as a plural, is the

undeclined form, and the singular is formed from it by adding a singular

ending.

(ii) Where objects are best known individnally; in this case the singular is

the undeclined form, and the plural is formed from it, either by internal

change of vowel or by the addition of a plural ending.

Formation of the Singular from the Collective Noun.

76 I. The singular is formed from the collective by adding the ending -yn to

form singulars masc.: -en to form singulars fem. Some collective nouns have a

masc. singular, others a feminine singular.

77 2. On adding a singular ending, the vowels

of the collective form must undergo the changes necessary when an ending is

added. See § 47, i, 6.

Examples: — adar, birds ader-yn; plant, children plent-yn; gwellt, grass

gwellt-yn, blade of grass; yd, corny yd-en, a grain of corn; plu, feathers

plu-en; sêr, stars ser-en; mellt, lightning, mellt-en, a flash of lightning.

Note 1 — The singular and the collective forms sometimes differ in meaning:

e.g, caws, cheese, cos-yn, ‘a cheese.'

Note 2. — To some singulars of this type, no collective form corresponds;

such singulars generally form plurals, for which see § 86.

Formation of the Plural of Nouns and Adjectives from the Singular.

78 Nouns and Adjectives, which have plural forms, form them either: —

(i) By internal change of vowel;

e,g, sant, saint; pl. saint; bychan, small, pl. bychain, or (ii) By the

addition of a plural ending:

e,g. llong, ship: pl. llong-au; du, black, pl. du-on.

79 Note. — Most adjectives have no plurals, and the singular form, even of

adjectives which have plurals, is not unfrequently used with plural nouns.

See Syntax, § 336.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7203) (tudalen 020)

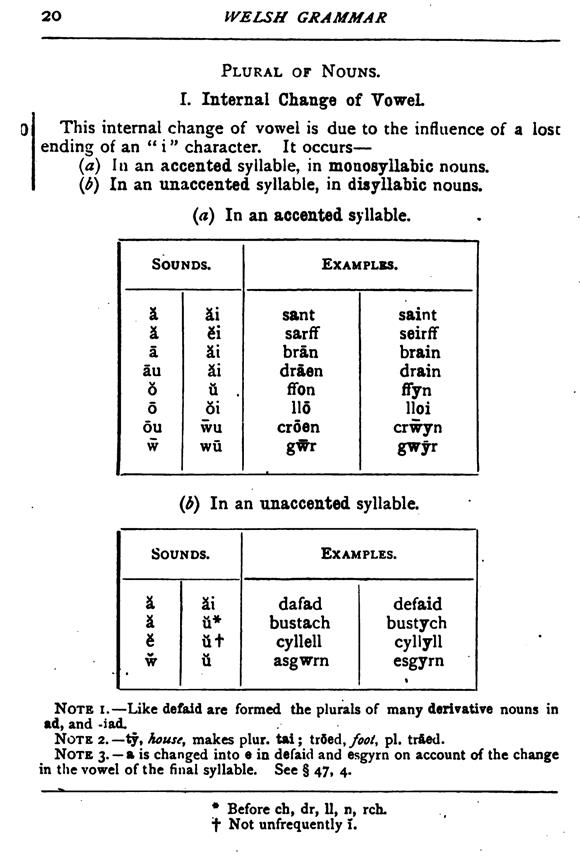

|

20 WELSH

GRAMMAR

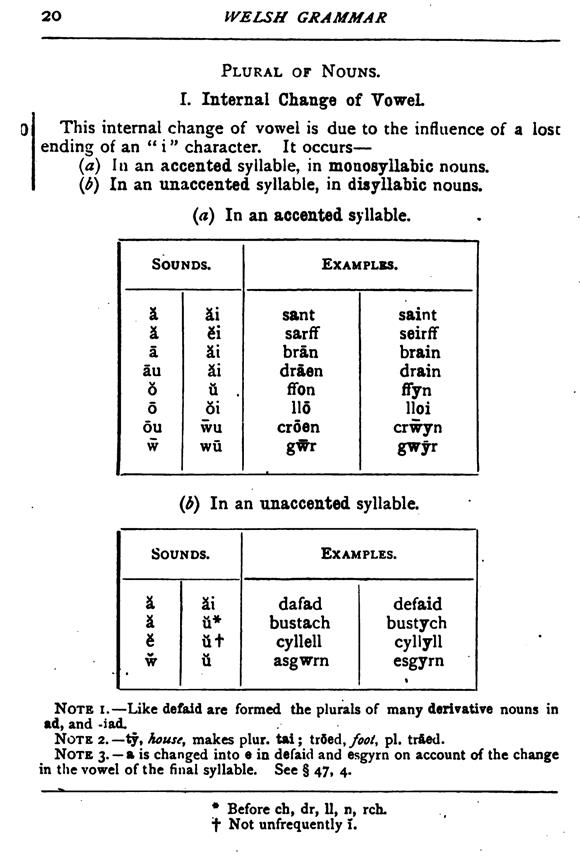

Plural of Nouns.

I.

Internal Change of VoweL

80 This

internal change of vowel is due to the influence of a lose ending of an

"i" character. It occurs —

{a) In an accented syllable, in moQOsyllabic nouns. {b) In an unaccented

syllable, in disyllabic nouns.

{a) In an accented syllable.

Sounds.

Examples.

H

i

sant

saint

H

li

sarflf

seirflf

a

i

bran

brain

au

i

draen

drain

5

ti .

ffon

ffyn

6

6i

Ho

lloi

ou

wu

croen

crwyn

w

wu

gWr

gwyr

(b) In an unaccented syllable.

Sounds.

Examples.

Ik

i

dafad

defaid

ii*

bustach

bustych

lit

cyllell

cyllyll

w

•

ii

asgwrn

esgyrn

Note i. — Like defaid are formed the plurals of many derivative nouns in ad,

and -iad.

Note 2.— ty, house makes plur. tai; tided, y/, pi. tr&ed.

Note 3. — a is changed into e in defaid and esgyrn on account of the change

in the vowel of the final syllable. See § 47, 4.

* Before ch, dr, 11, n, rch. t Not unfrcquently 1.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7204) (tudalen 021)

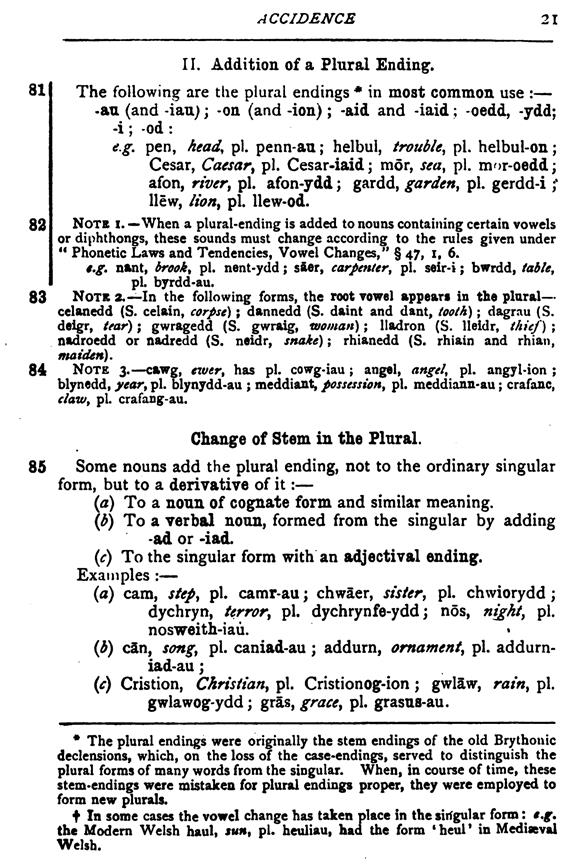

|

ACCIDENCE

21

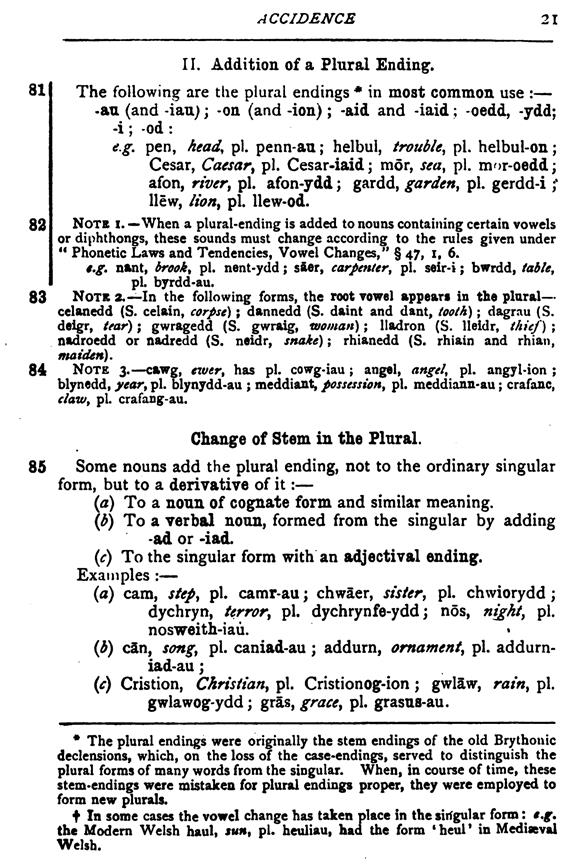

II. Addition of a Plural Ending.

81 The following are the plural endings * in most common use: — -an (and

-iau; -on (and -ion); -aid and -laid; -oedd, -ydd;

-i; -od:

e.g, pen, head pi. penn-au; helbul, trouble pi. helbul-on;

Cesar, Caesar pi. Cesar-iaid; mor, sea pi. mor-oedd;

afon, river y pi. afon-ydd; gardd, garden pi. gerdd-i;

Hew, lion pi. llew-od.

82 NoTB I. —When a plural-ending is added to nouns containing certain vowels

or diphthongs, these sounds must change according to the rules given under

" Phonetic Laws and Tendencies, Vowel Changes," § 47, i, 6.

€.g, nant, brooks pi. nent-ydd; saer, carpenter pi. seir-i; bwrdd, table, pL

byrdd-au.

83 NoTR 2.— In the following forms, the root vowel appeari in the plaral—

celanedd (S. celain, corpse); dannedd (S. daint and dant, tooth); dagrau (S.

deigr, tear \ gwragedd (S. gwraig, woman); Iladron (S. lleidr, thief);

nadroedd or nadredd (S. neidr, snake); rhianedd (S. rhiain and rhian,

tnaidev.

84 Note 3. — cawg, ewer, has pi. cowg-iau; angel, angel, pi. angyMon; blynedd,

year pi. blynydd-au; meddiant, possession, pi. meddiann-au; crafanc, claWy

pi. crafang-au.

Change of Stem in the Plural.

85 Some nouns add the plural ending, not to the ordinary singular form, but

to a derivative of it: —

{a) To a noun of cognate form and similar meaning.

\b) To a verbal noun, formed from the singular by adding

-ad or -lad. {c) To the singular form with an adjectival ending. Examples: —

{a) cam, step pi. camr-au; chwaer, sister, pi. chwiorydd;

dychryn, terrory pi. dychrynfe-ydd; nos, nighty pi.

nosweith-iau. (3) cSn, song, pi. caniad-au; addurn, ornament, pi. addurn-

iad-au; {c) Cristion, Chrisiiany pi. Cristionog-ion; gwlaw, rain, pi.

gwlawog-ydd; gras, grace, pi. grasus-au.

* The plural endings were originally the stem endings of the old Brythonic

declensions, which, on the loss of the case-endings, served to distinguish

the plural forms of many words from the singular. When, in course of time,

these stem-endings were misten for plural endings proper, they were employed

to form new plurals.

f In some cases the vowel change has taken place in the siifgular form: 9,g,

the Modern Welsh haul, tun, pi. heuliau, had the form *heui* in Mediaeval

Welsh.

|

|

|

|

|

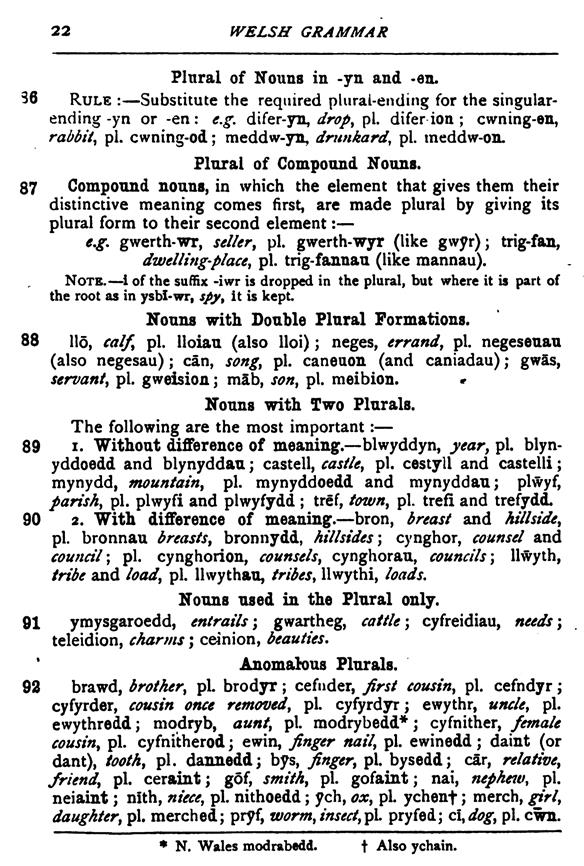

(delwedd F7205) (tudalen 022)

|

22 WELSH

GRAMMAR

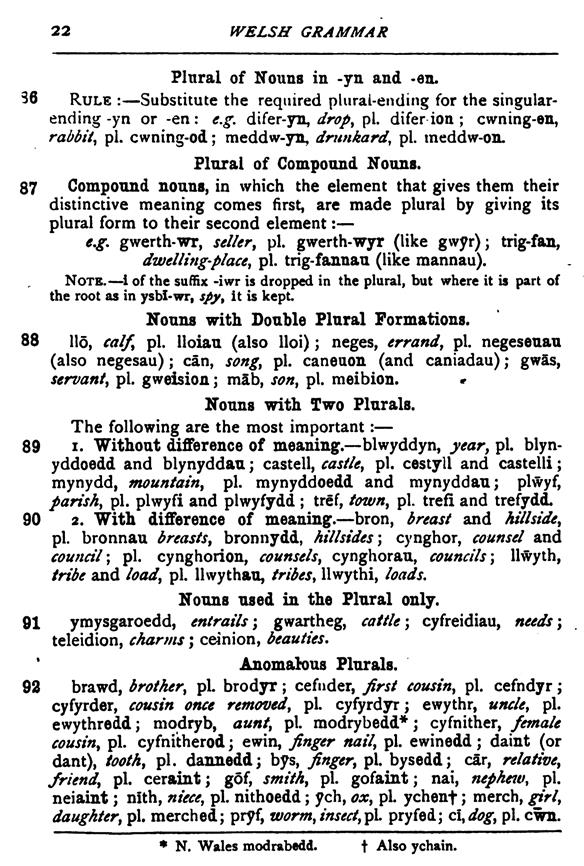

Plural of Nouns in -yn and -en.

36 Rule: — Substitute the required plural-ending for the singular-ending -yn

or -en: eg, difer-jn, drop pi. difer ion; cwning-en, rabbity pi. cwning-od;

meddw-yn, drunkard, pi. meddw-on.

Plural of Compound Nouns.

87 Compound nouns, in which the element that gives them their distinctive

meaning comes first, are made plural by giving its plural form to their

second element: —

e,g. gwerth-wr, seller pi. gwerth-wyr (like gwyr); trig-fan,

dwelling-place pi. trig-fannau (like mannau).

Note. — i of the suffix -iwr is dropped in the plural, but where it is part

of the root as in ysbi-wr, spy it is kept.

Nouns with Double Plural Formations.

88 116, calf pi. lloiau (also lloi); neges, errand, pi. negeseuau (also

negesau); can, song, pi. caneuon (and caniadau); gwls, servant, pi. gweision

\ mab, son, pi. meibion. *

Nouns with Two Plurals.

The following are the most important: —

89 I. Without difference of meaning.— blwyddyn, year, pi. blynyddoedd and

blynyddau; castell, castle, pi. cestyll and castelli; mynydd, mountain, pi.

mynyddoedd and mynyddau; plwyf, parish, pi. plwyfi and plwyfydd; tref, town,

pi. trefi and trefydd.

90 2. With difference of meaning. — bron, breast and hillside, pi. bronnau

breasts, bronnydd, hillsides', cynghor, counsel and council', pi. cynghorion,

counsels, cynghorau, councils', llwyth, tribe and load, pi. llwythau, tribes,

llwythi, loads.

Nouns used in the Plural only.

91 ymysgaroedd, entrails *, gwartheg, cattle', cyfreidiau, needs 'y

teleidion, charms; ceinion, beauties.

Anomalous Plurals.

92 brawd, brother, pi. brodyr; cefnder, first cousin, pi. cefndyr; cyfyrder,

cousin once removed, pi. cyfyrdyr; ewythr, uncle, pi. ewythredd; modryb,

aunt, pi. modrybedd*; cyfnither, female cousin, pi. cyfnitherod; ewin, finger

nail, pi. ewinedd; daint (or dant), tooth, pi. dannedd; bys, finger, pi.

bysedd; car, relative,

friend, pi. ceraint; gof, smith, pi. gofaint; nai, nepheiv, pi. neiaint;

nith, niece, pi. nithoedd; ych, ox, pi. ychenf; merch, girl, daughter, pi.

merched; pryf, worm,insect,\, pryfed; ci,dog, pi. cwn.

* N. Wales modrabedd. f Also ychain.

|

|

|

|

|

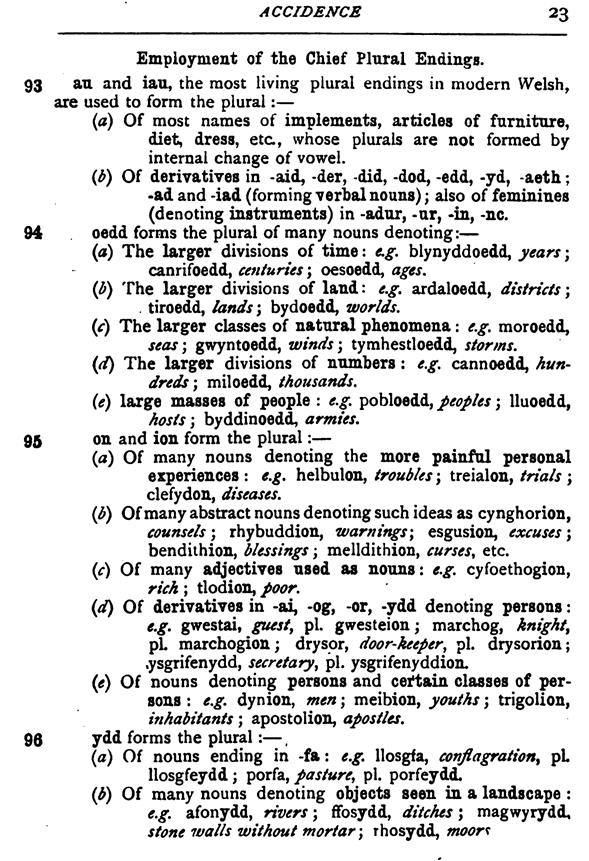

(delwedd F7206) (tudalen 023)

|

ACCIDENCE

23

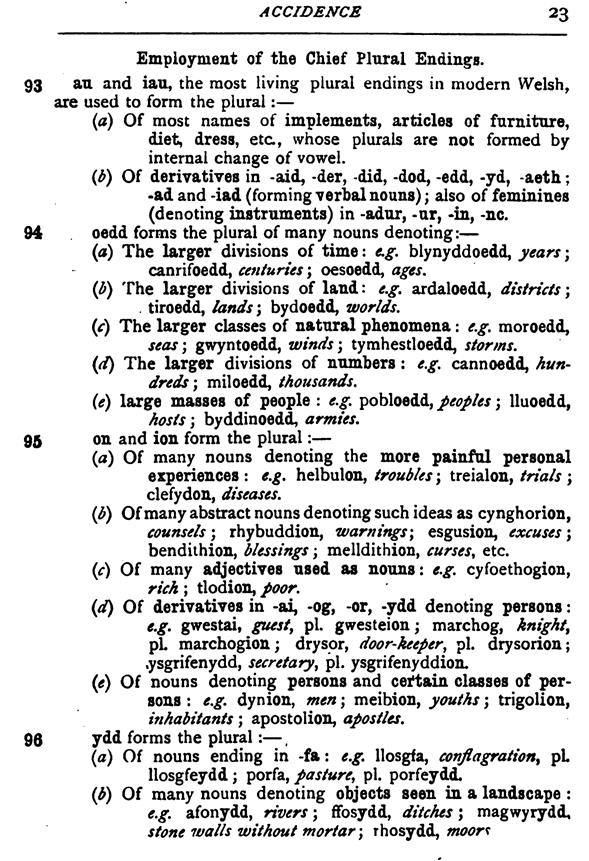

Employment of the Chief Plural Endings.

93 an and ian, the most living plural endings in modern Welsh, are used to

form the plural: —

(a) Of most names of implements, articles of furniture,

diet, dress, etc, whose plurals are not formed by internal change of vowel.

(b) Of derivatives in -aid, -der, -did, -dod, -edd, -yd, -aeth;

-ad and -iad (forming verbal nouns); also of feminiues (denoting instruments)

in -adur, -ur, -in, -no.

94 oedd forms the plural of many nouns denoting: —

(a) The larger divisions of time: e.g, blynyddoedd, years;

canrifoedd, centuries \ oesoedd, ages. s (Ji) The larger divisions of laud:

e,g. ardaloedd, districts;

tiroedd, lands \ bydoedd, worlds,

(c) The larger classes of natural phenomena: e,g, moroedd,

secLS\ gwyntoedd, winds \ tymhestloedd, storms, {d) The larger divisions of

numbers: e,g, cannoedd, hundreds] miloedd, thousands, (e) large masses of

people: e.g. pobloedd, peoples \ Uuoedd, hosts \ byddinoedd, armies, \ 95 on

and ion form the plural: —

{a) Of many nouns denoting the more painful personal experiences: e,g,

helbulon, troubles \ treialon, trials \ clefydon, diseases,

(b) Of many abstract nouns denoting such ideas as cynghorion, ( counsels; rhybuddion,

warnings; esgusion, excuses;

bendiihion, blessings -, melldithion, curses, etc. {c) Of many adjectives

used as nouns: e,g, cyfoethogion, rich; tlodion, poor,

(d) Of derivatives in -ai, -og, -or, -ydd denoting persons: e,g. gwestai,

guest, pi. gwesteion; marchog, knight, pL marchogion; drysor, door-keeper,

pi. drysorion; .ysgrifenydd, secretary, pi. ysgrifenyddion.

() Of nouns denoting persons and ceftain classes of persons: e,g, dynion, men

\ meibion, youths \ trigolion, inhabitants \ apostolion, apostles, 96 ydd

forms the plural: — .

\a) Of nouns ending in -fa: e,g, llosgfa, conflagration, pL llosgfeydd;

porfsL, pasture, pi. porfeydd.

{b) Of many nouns denoting objects seen in a landscape: e.g, afonydd, rivers;

ffosydd, ditches; magwyrydd, stone walls without mortar-, rhosydd, moor

)

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7207) (tudalen 024)

|

24

WELSH GRAMMAR

98

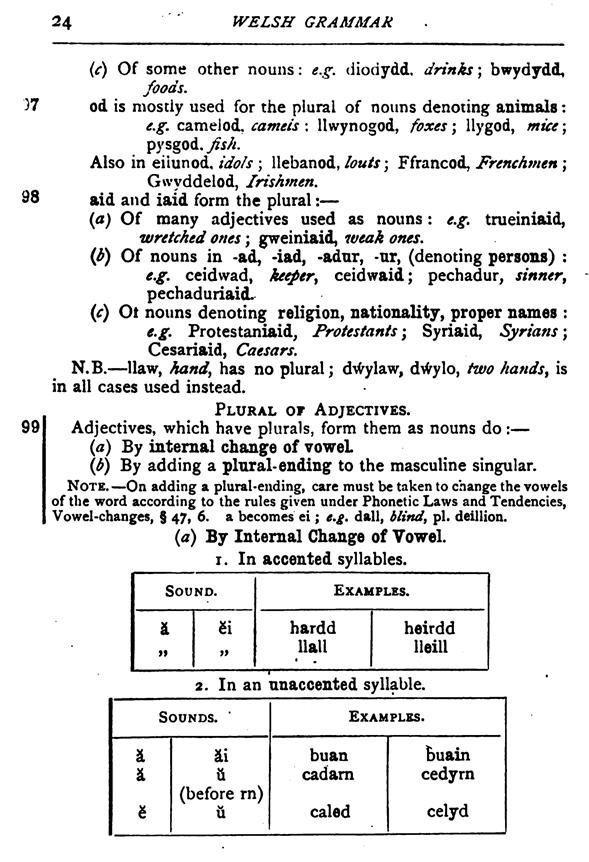

(r) Of some other nouns: e.g, diodydd, drinks; bwydydd, foods, yt od is

mostly used for the plural of nouns denoting animals:

e,g. camelod, cameis; llwynogod, foxes; llygod, mice; pysgod, fish. Also in

eilunod, idols; llebanod, louts-, Ffrancod, Frenchmen;

Gwyddelod, Irishmen. aid and iaid form the plural: — {a) Of many adjectives

used as nouns: e.g, trueiniaid,

wretched ones; gweiniaid, 7veak ones, (b) Of nouns in -ad, -iad, -adur, -nr,

(denoting persons): e,g. ceidwad, keeper ceidwaid; pechadur, sinner

pechaduriaid. {c) Ot nouns denoting religion, nationality, proper names: e.g,

Protestaniaid, Protestants -y Syriaid, Syrians) Cesariaid, Caesars. N.B. —

Haw, handy has no plural; d'virylaw, dylo, two hands, is in all cases used

instead.

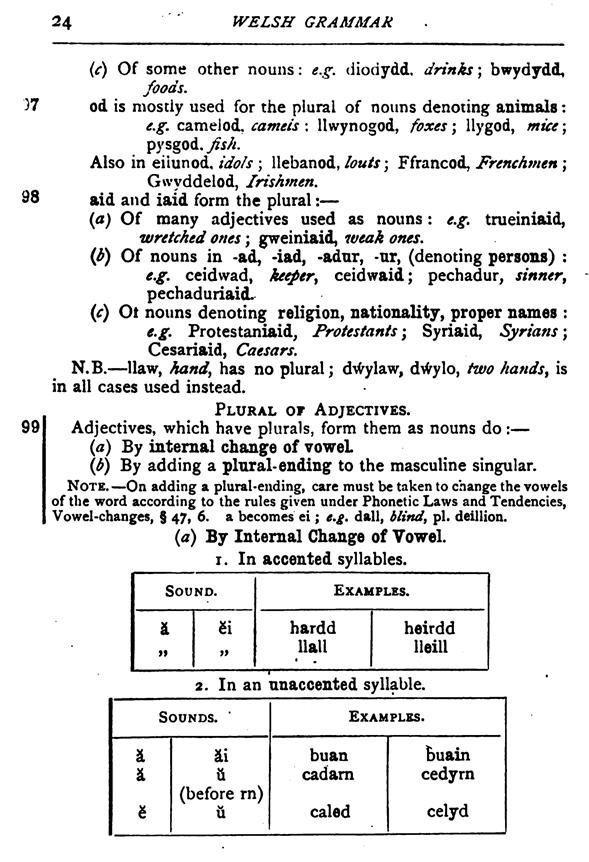

Plural of Adjectives. 99 Adjectives, which have plurals, form them as nouns

do: — (a) By internal change of voweL {b) By adding a plural- ending to the

mascuHne singular.

Note. — On adding a plural-ending, care must be taken to change the vowels of

the word according to the rules given under Phonetic Laws and Tendencies,

Vowel-changes, § 47, 6. a becomes ei; e,g, dall, blind, pi. deillion.

{a) By Internal Change of Vowel. I. In accented syllables.

Sound.

Examples.

>9

Si

hardd Hall

heirdd lleill

2. In an unaccented syllable.

Sounds.

Examples.

g

i

ii

(before rn)

ii

buan cadam

caled

buain cedyrn

celyd

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7208) (tudalen 025)

|

ACCIDENCE

25

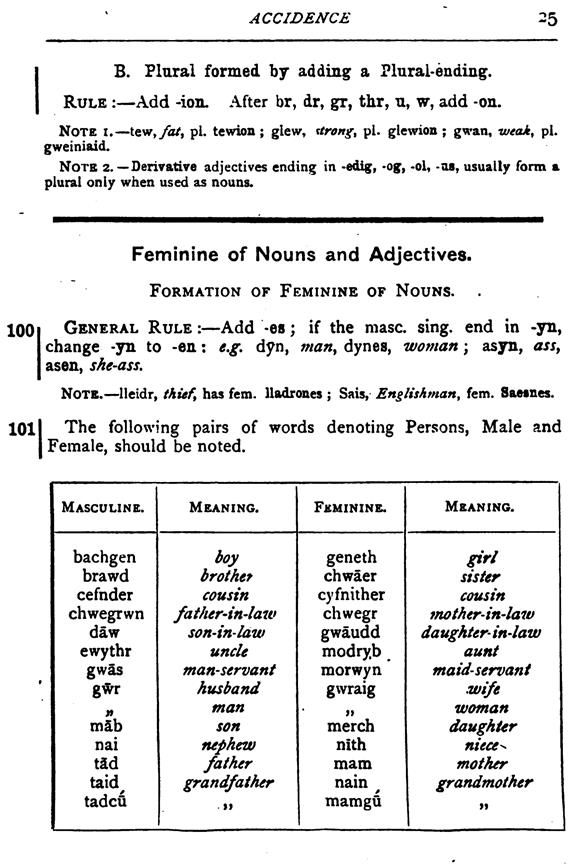

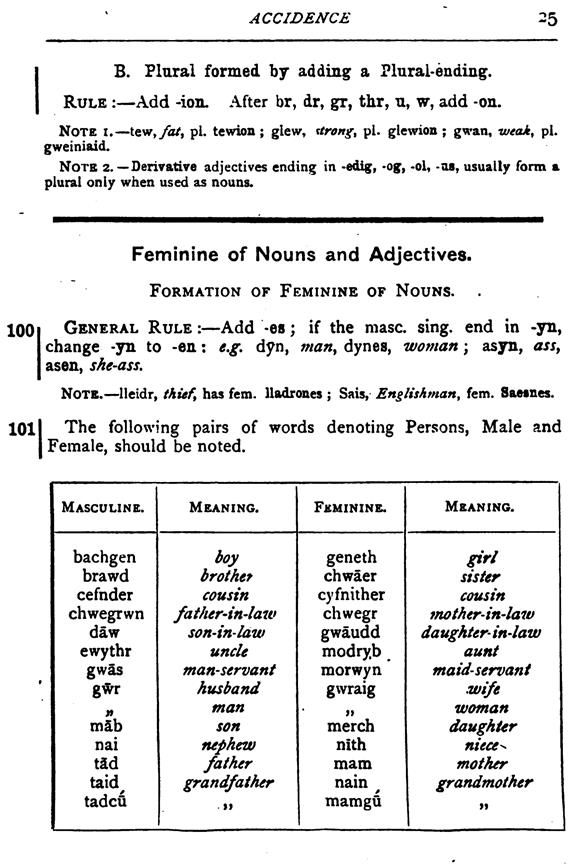

B. Plural formed by adding a Plural-ending. Rule: — Add -ion. After br, dr,

gr, thr, u, w, add -on.

Note i. — tew,ya/, pi. tewion; glew, strong, pi. glewion; gwan, tveak pi.

gweiniaid.

Note 2. ~ Derivative adjectives ending in -edig, -og, -ol, -as, usually form

a plural only when used as nouns.

Feminine of Nouns and Adjectives.

Formation of Feminine of Nouns.

100 General Rule: — Add -es; if the masc. sing, end in -yn, change -yn to

-en: e,g, dyn, matiy dynes, woman; asyn, ass asen, she-ass,

NoTB. — lleldr, thieft has fem. Uadrones; Sals, Englishman, fern. Saesnes.

101 1 The following pairs of words denoting Persons, Male and I Female,

should be noted.

Masculine.

Meaning.

Feminine.

Meaning.

bachgen

boy

geneth

girl

brawd

brother

chwaer

sister

cefnder

cousin

cyfnither

cousin

chwegrwn

father-in-laxv

chwegr

fnother-in-law

daw

son-in-law

gwaudd

daughter- in-law

ewythr

uncle

modryb

aunt

gwas

man-servant

morwyn

maidservant

gr

husband

gwraig

wife

it

man

a

woman

mab

son

merch

daughter

nai

nephew

nith

ntece

tad

father

mam

mother

taid

grandfather

nam

grandmother

tadcu

■ »»

mamgu

>«

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7209) (tudalen 026)

|

26 WELSH

GRAMMAR

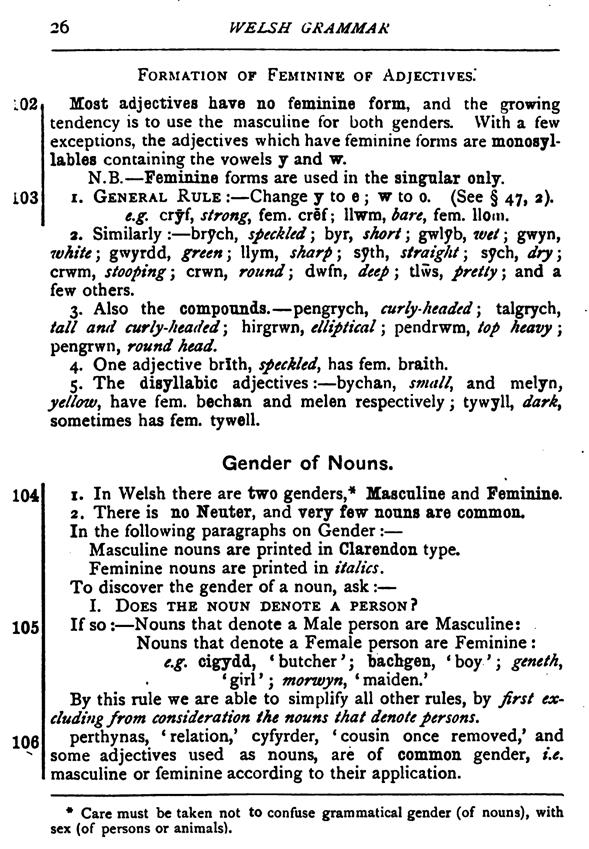

102

i03

104

105

106

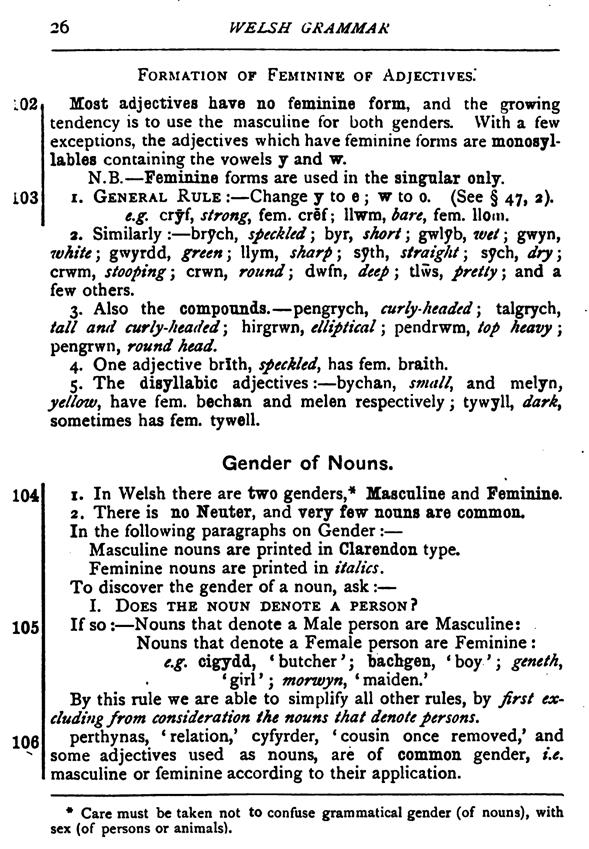

Formation of Feminine of Adjectives.*

Most adjectives have no feminine form, and the growing tendency is to use the

masculine for both genders. With a few exceptions, the adjectives which have

feminine forms are monosyllables containing the vowels y and w.

N.B. — Feminine forms are used in the singular only.

1. General Rule: — Change y to e; w to o. (See § 47, 2).

e,g, cryf, strong fem. cref; Uwm, bare fem. Uoin.

2. Similarly: — brych, speckled \ byr, short \ gwlyb, ivet \ gwyn, 7vhtte\

gwyrdd, green \ llym, sharp \ syth, straight \ sych, dry\ crwm, stooping;

crwn, round; dwfn, deep; tlws, pretty; and a few others.

3. Also the compotinds. — pengrych, curly- headed \ talgrych, tall and

curly-headed', hirgrwn, elliptical \ pendrwm, top heavy \ pengrwn, round

head,

4. One adjective brith, speckled has fem. braith.

5. The disyllabic adjectives: — bychan, stnall, and melyn, yellow, have fem.

bechan and melen respectively; tywyll, dark sometimes has fem. tywell.

Gender of Nouns.

*

1. In Welsh there are two genders/ Masculine and Feminine.

2. There is no Neuter, and very few nouns are common. In the following

paragraphs on Gender: —

Masculine nouns are printed in Clarendon type. Feminine nouns are printed in

italics. To discover the gender of a noun, ask: —

I. Does the noun denote a person? If so: — Nouns that denote a Male person

are Masculine: Nouns that denote a Female person are Feminine: e,g, cigydd,

'butcher'; bachgen, *boy'; geneth, * girl '; morwyn, * maiden.* By this rule

we are able to simplify all other rules, by first excluding from

consideration the nouns that denote persons,

perthynas, * relation,* cyfyrder, * cousin once removed,' and some adjectives

used as nouns, are of common gender, i,e, masculine or feminine according to

their application.

* Care must be taken not to confuse grammatical gender (of nouns), with sex

(of persons or animals).

107

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7210) (tudalen 027)

|

ACCIDENCE

27

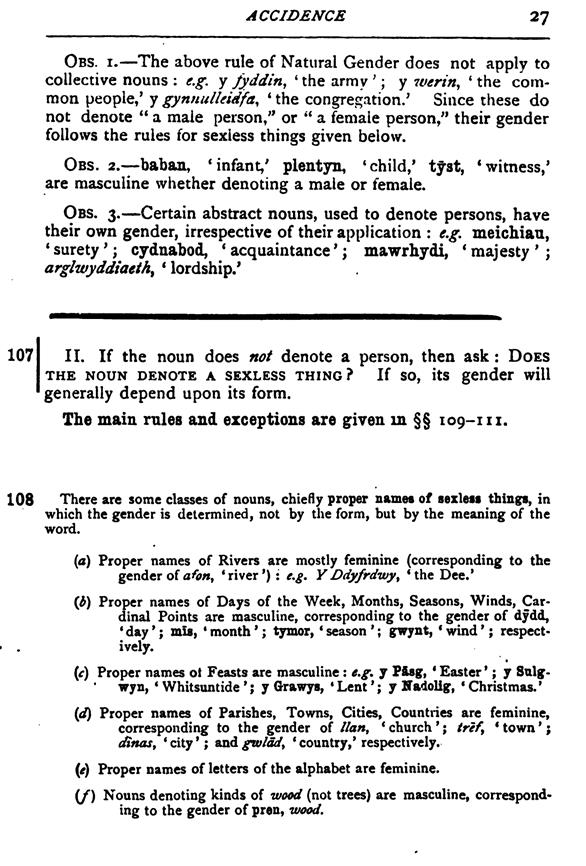

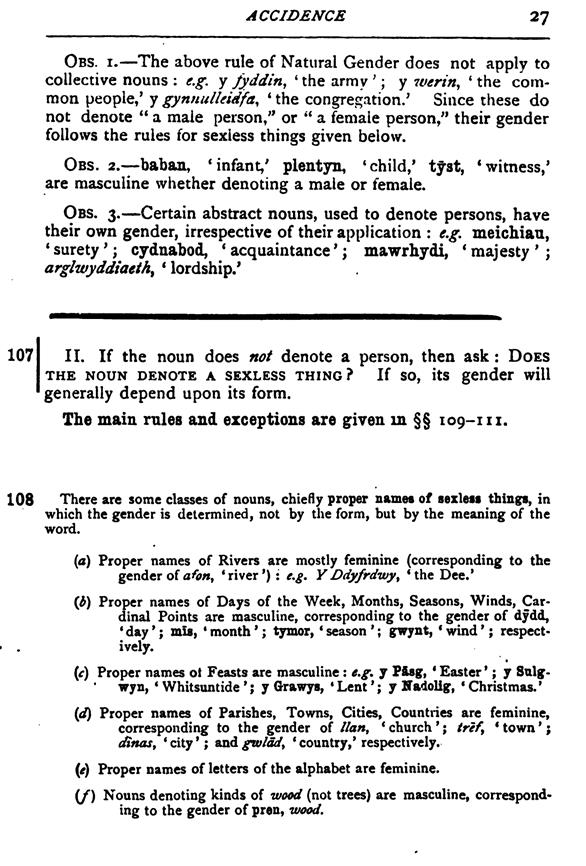

Obs. I. — The above rule of Natural Gender does not apply to collective

nouns: e.g. y fyddin 'the army '; y werin., ‘the common people,’ y

gynnulleidfa, ‘the congregation.’ Since these do not denote "a male

person” or "a female person," their gender follows the rules for

sexless things given below.

Obs. 2. — baban, * infant,' plentyn, * child,' tyst, 'witness,' are masculine

whether denoting a male or female.

Obs. 3. — Certain abstract nouns, used to denote persons, have their own

gender, irrespective of their application: e,g. meichiau, * surety ';

cydnabod, * acquaintance '; mawrhydi, * majesty '; arglwyddiaeih * lordship.'

II. If the noun does not denote a person, then ask: Does

THE NOUN DENOTE A SEXLESS THING? If SO, itS gender wlll

generally depend upon its form. The main rules and exceptions are given in §§

109-111.

108 There are some classes of nouns, chiefly proper names of sexleii things,

in which the gender is determined, not by the form, but by the meaning of the

word.

(a) Proper names of Rivers are mostly feminine (corresponding to the gender

of an, * river*): e.g, Y Ddyfrdwy *the Dee.*

iff) Proper names of Days of the Week, Months, Seasons, Winds, Cardinal

Points are masculine, corresponding to the gender of dydd, * day *; mis, *

month *; tymor, * season *; gwynt, * wind *; respectively.

•

(r) Proper names ot Feasts are masculine: e.g, j F&sg, * Easter *; y

Snlgwyn, * Whitsuntide *; y Grawys, • Lent *; y ITadolig, « Christmas.*

{d) Proper names of Parishes, Towns, Cides, Countiies are feminine,

corresponding to the gender of //«», * church *; tref * town *; cncUf * city

*; and gw/dd, * country,* respectively.

{e) Proper names of letters of the alphabet are feminine.

(/) Nouns denoting kinds of wood (not trees) are masculine, corresponding to

the gender of pren, wood.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7211) (tudalen 028)

|

28 WELSH

GRAMMAR

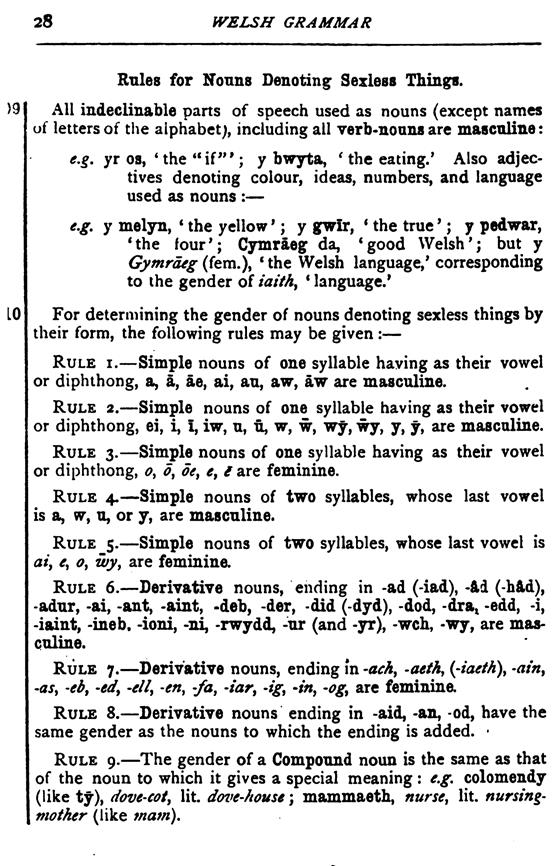

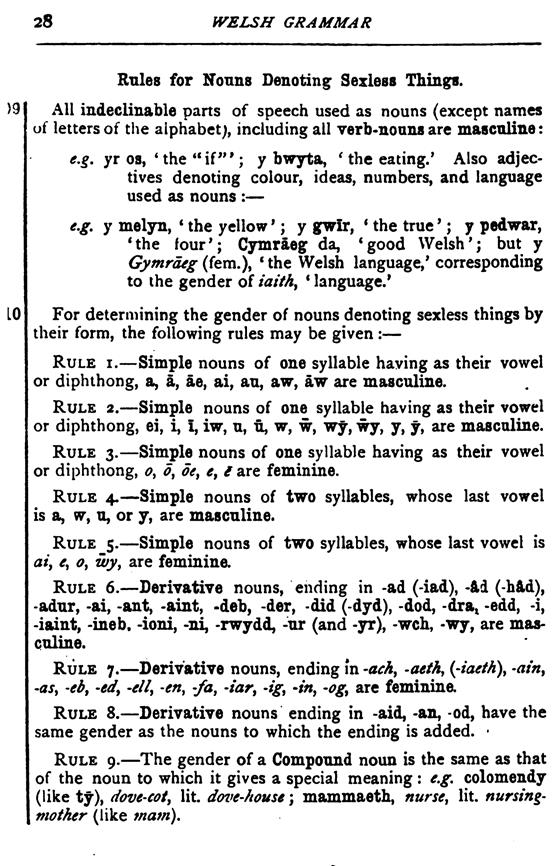

Rules for Nonns Denoting Sexless Things.

)9 All indeclinable parts of speech used as nouns (except names uf letters of

the alphabet;, including all verb-nonns are masctiline:

e.g. yr os, * the "if"; y bwyta, ' the eating.' Also adjectives

denoting colour, ideas, numbers, and language used as nouns: —

e.g. y melyn, * the yellow '; y gwir, * the true '; y pedwar, *the four';

Cymraeg da, *good Welsh'; but y Gymrdeg (fem.), * the Welsh language,' corresponding

to the gender of iaith * language.'

LO For determining the gender of nouns denoting sexless things by their form,

the following rules may be given; —

Rule i. — Simple nouns of one syllable haying as their vowel or diphthong, a,

a, ae, ai, au, aw, aw are masculine.

Rule 2. — Simple nouns of one syllable having as their vowel or diphthong,

ei, i, i, iw, u, u, w, w, wy, wy, y, y, are masculine.

Rule 3. — Simple nouns of one syllable having as their vowel or diphthong,

<?, J, J<f, , i are feminine.

Rule 4. — Simple nouns of two syllables, whose last vowel is a, w, a, or y,

are masculine.

Rule 5. — Simple nouns of two syllables, whose last vowel is ai e o wy, are

feminine.

Rule 6. — Derivative nouns, ending in -ad (-iad), -ftd (-hftd), -adnr, -ai,

-ant, -aint, -deb, -der, -did (dyd), -dod, -draj -edd, -i, -iaint, -ineb.

-ioni, -ni, -rwydd, -nr (and -yr), -wch, -wy, are masculine.

Rule 7. — Derivative nouns, ending in -acA, -aeth, {-iaeth), -ainy -as, -eby

-edy -elly -en, -fa, -iar -ig, -in, -og are feminina

Rule 8. — Derivative nouns ending in -aid, -an, -od, have the same gender as

the nouns to which the ending is added. •

Rule 9. — The gender of a Compound noun is the same as that of the noun to

which it gives a special meaning: e.g. colomendy (like ty), dove-cot, lit.

dove-house; mammaeth, nurse, lit. nursing-mother (like mam).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7212) (tudalen 029)

|

ACCIDENCE

29

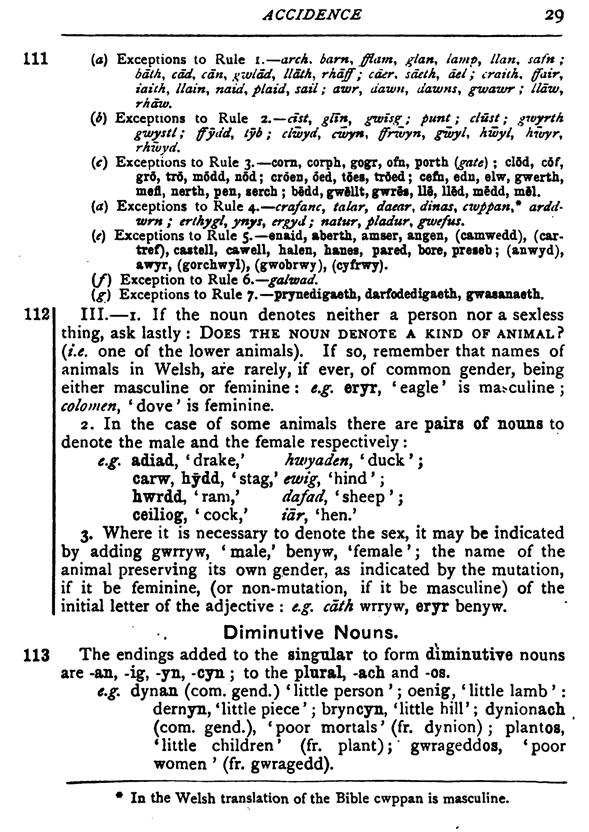

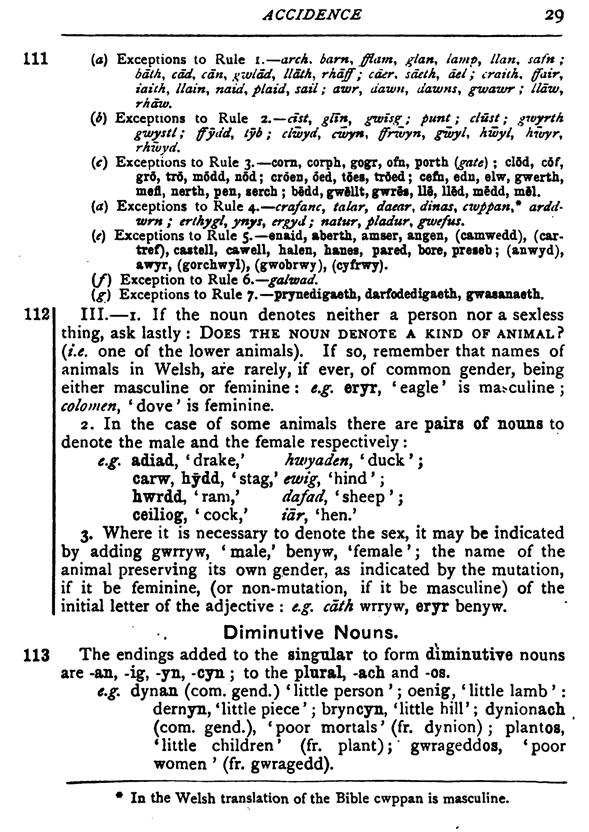

111 (tf) Exceptions to Rule l. — arcA, bam fidffty glan iampj llan safn;

bdih cdd cdn jzvlddy llcUh rhdff; cder sdeih, del; craith ff<iit

iaith llain, natd plaidy sail; awr dawn dawnsy gwawr; lldWy

rhdw, {b) Exceptions to Rule 2.— cist, gitn, Sjisg; punt; dust; gwyrth

gwystl; ffyddy tyb; clwydy cwyn, ffrwyn, gwyl hwyl, hvyr

rhwvd, {e) Exceptions to Rule 3. — com, corph,?o, ofii, porth [gate); clod,

cdf,

grd, tro, modd, nod; croeo, ded, tdes, trded; cefii, edu, elw, gwerth,

mefl, north, pen, serch; bedd, gwSUt, gwrii, 11§, llSd, medd, mSl. {a)

Exceptions to Rule 4. — crafanc, talar, daear, dittos, civppan* ardd-

wm; erthygl, ynys, ergyd; natur, piadur, gwefus, [e) Exceptions to Rule 5. —

enaid, aberth, amser, angen, (camwedd), (car-

tref), castell, cawell, halen, banes, pared, bore, preieb; (anwyd),

awyr, (gorchwyl), (gwobrwy), (cyfrwy). (/) Exception to Rule 6,'—galwad, {g)

Exceptions to Rule 7.— prynedigaeth, darfodedigaeth, gwasanaeth.

112 III. — I. If the noun denotes neither a person nor a sexless thing, ask

lastly: Does the noun denote a kind of animal? {i,e. one of the lower

animals). If so, remember that names of animals in Welsh, are rarely, if

ever, of common gender, being either masculine or feminine: e,g. eryr, *

eagle * is masculine; colomen, * dove ' is feminine.

2. In the case of some animals there are pairs of nouns to denote the male

and the female respectively:

eg, adiad, * drake,* hwyaden, * duck '; carw, hydd, *stag,' ewtg *hind';

hwrdd, * ram,' dafad, * sheep ';

ceiliog, *cock,' idr, *hen.'

3. Where it is necessary to denote the sex, it may be indicated by adding

gwrryw, * male,' benyw, *female '; the name of the animal preserving its own

gender, as indicated by the mutation, if it be feminine, (or non-mutation, if

it be masculine) of the initial letter of the adjective: e,g, cdth wrryw,

eryr benyw.

Diminutive Nouns.

113 The endings added to the singular to form diminutive nouns are -an, -ig,

-yn, -cyn \ to the plural, -ach and -os.

e.g. dynan (com. gend.) Mittle person '; oenig, * little lamb ': dernjrn,

'little piece*; bryncyn, 'little hiir; dynionach (com. gend.), 'poor mortals'

(fr. dynion); plantos, 'little children* (fr. plant);' gwrageddos, *poor

women ' (fr. gwragedd).

* In the Welsh translation of the Bible cwppan is masculine.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7213) (tudalen 030)

|

30

WELSH GRAMMAR

115

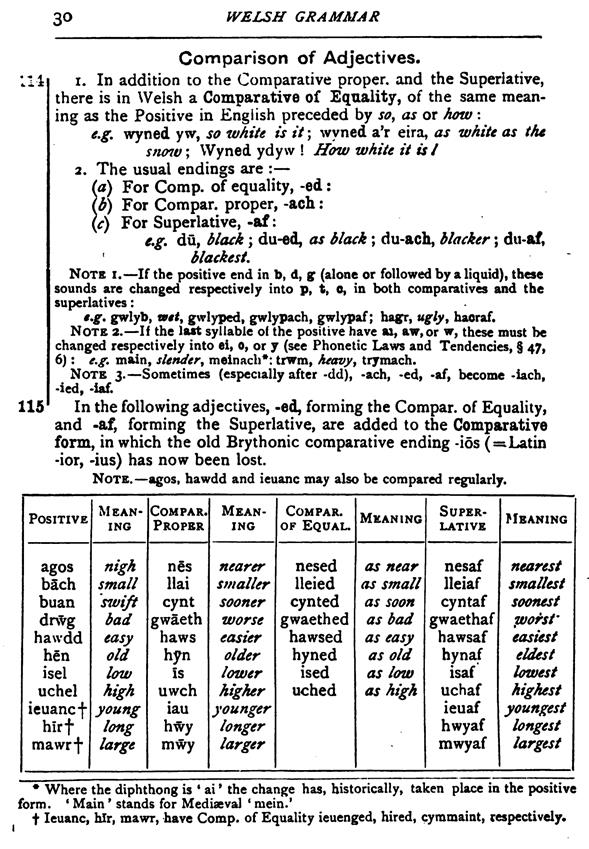

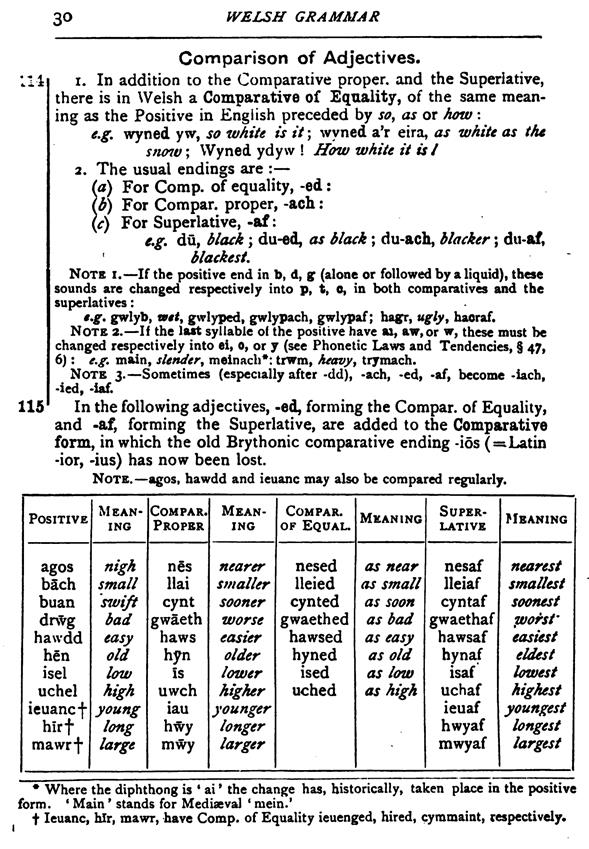

Comparison of Adjectives.

1. In addition to the Comparative proper, and the Superlative, there is in

Welsh a Comparative of Equality, of the same meaning as the Positive in

English preceded by so as or how:

e,g. wyned y w, so white is it; wyned a'r eira, as white as the sfunv; Wyned

ydy \v! How white it is i

2. The usual endings are:—

a) For Comp. of equality, -ed:

b) For Compar. proper, -ach: \c) For Superlative, -af:

e,g. du, black; du-ed, as black; du-ach, blacker; du-af, blackest. Note i. —

If the positive end in b, d, g (alone or followed by a liquid), these sounds

are changed respectively into p, t, e, in both comparatives and the

superlatives:

e.g* gwlyb, wei gwlyped, gwlypach, gwlypaf; hagr, ugly haoraf. Note 2. — If

the last syllable of the positive have ai, aw, or w, these must be changed

respectively into ei, 0, or y (see Phonetic Laws and Tendencies, § 47, 6):

e.g, main, slender main ach*: trwm, htavyy trymach.

Note 3. — Sometimes (especially after -dd), -ach, -ed, -af, become -iach,

•led, -iaf.

In the following adjectives, -ed, forming the Compar. of Equality, and -af,

forming the Superlative, are added to the Comparative form, in which the old

Brythonic comparative ending -ids (= Latin -ior, -ius) has now been lost.

Note. — agos, hawdd and ieuanc may also be compared regularly.

Positive

Meaning

Compar. Proper

Meaning

agos

nigh

nes

nearer

bach

small

llai

smaller

buan

swift

cynt

sooner

dnvg

bad

gwaeth

worse

hawdd

easy

haws

easier

hen

old

hyn

older

isel

low

is

lower

uchel

high

uwch

higher

ieuanc f

young

lau

younger

hirt

long

hwy

longer

mawrf

large

mwy

larger

Compar. OF Equal.

Meaning

Superlative

PIeaning

nesed

as near

nesaf

nearest

lleied

as small

lleiaf

smallest

cynted

as soon

cyntaf

soonest

gwaethed

as bad

gwaethaf

pjorst'

hawsed

as easy

hawsaf

ecuiest

hyned

as old

hynaf

eldest

ised

as low

isaf

lowest

uched

as high

uchaf

highest

ieuaf

youngest

hwyaf

longest

•

mwyaf

largest

♦ Where the diphthong is * ai * the change has, historically, taken

place in the positive form. * Main ' stands for Mediaeval ' mein.' t Ieuanc,

hir, mawr, have Comp. of Equality ieuenged, hired, cymmaint, respectively.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7214) (tudalen 031)

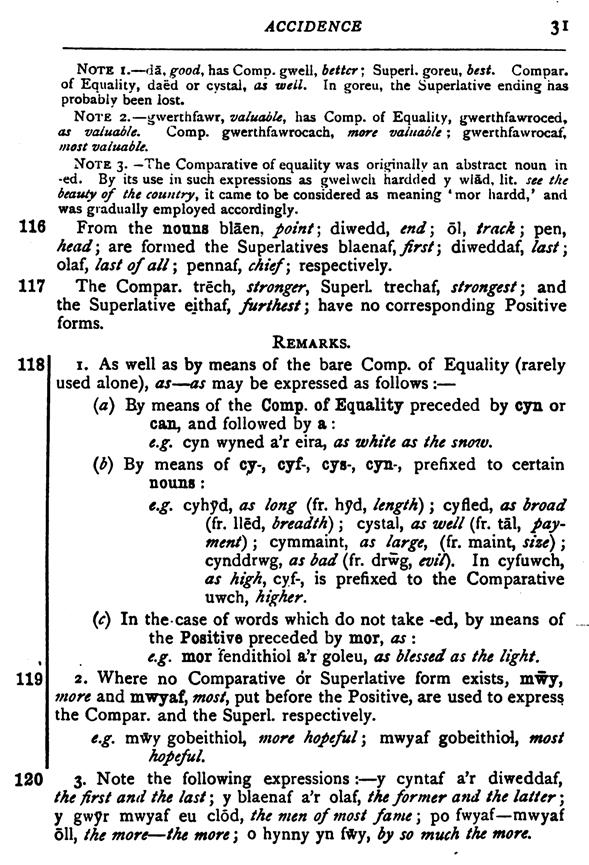

|

ACCIDENCE

31

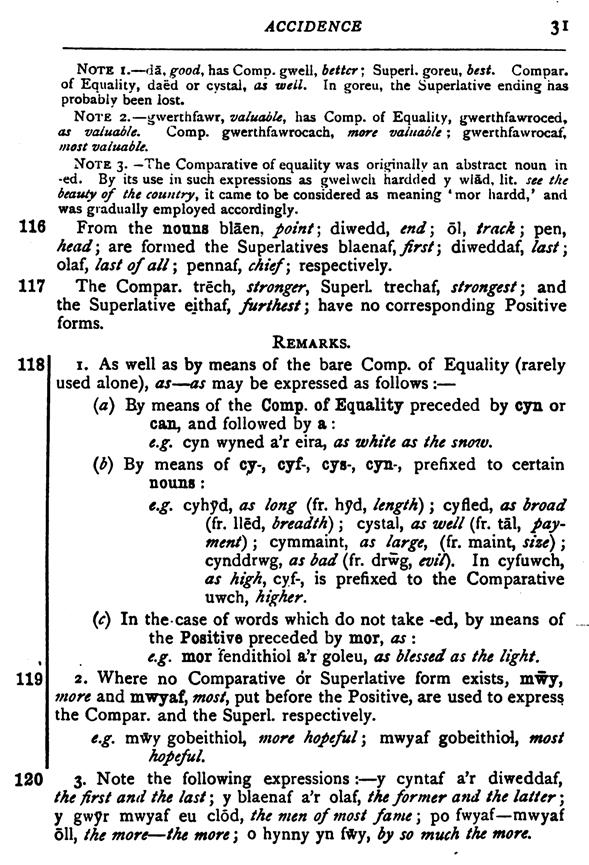

Note i. — da, good, has Comp. gweli, better; Superi. goreu, best, Compar. of

Equality, daed or cystai, as well. In goreu, the Superlative ending has

probably been lost.

Note 2. — gwerthfawr, valuabU has Comp. of Equality, gwerthfawroced, as

vaiuadie. Comp. gwerthfawrocach, more valuable; gwerthfawrocaf, most

valuable.

Note 3. —The Comparative of equality was originally an abstract noun in •ed.

By its use in such expressions as gwehvch hardded y wiS.d, lit. see the

beauty of the country it came to be considered as meaning *mor hardd,* and

was gradually employed accordingly.

116 From the nouns blaen, point \ diwedd, end\ 61, track \ pen, head\ are

formed the Superlatives blaenaf,yfrj/; diweddaf, last\ olaf, last of all 'y

pennaf, chief \ respectively.

117 The Compar. trech, stronger SuperL trechaf, strongest', and the

Superlative eithaf, furthest', have no corresponding Positive forms.

Remarks.

118 I. As well as by means of the bare Comp. of Equality (rarely used alone),

as — as may be expressed as follows: —

{a) Ry means of the Comp. of Equality preceded by C3m or can, and followed by

a: e.g, cyn wyned a'r eira, as white cts the snmv,

{p) By means of cy-, cyf-, cys-, cyn-, prefixed to certain nouns:

e,g, cyhyd, as long (fr. hyd, length); cyfled, as broad (fr. lled, breadth) \

cystai, cts well (fr. tal, payment); cymmaint, as large, (fr. maint, size);

cynddrwg, as bad (fr. drwg, evil). In cyfuwch, as high, cyf-, is prefixed to

the Comparative uwch, higher,

{c) In the case of words which do not take -ed, by means of the Positive

preceded by mor, cts: e,g, mor fendithiol a'r goleu, as blessed as the light,

119 2. Where no Comparative or Superlative form exists, mwy, more and mwyaf,

most, put before the Positive, are used to express the Compar. and the

Superi. respectively.

e,g, mwy gobeithiol, more hopeful', mwyaf gobeithiol, most hopeful,

120 3. Note the following expressions: — y cyntaf a'r diweddaf, the first and

the last', y blaenaf a'r olaf, the former and the latter', y gwyr mwyaf eu

clod, the men of most fame; po fwyaf — mwyaf 611, the more — the more j o

hynny yn fWy, by so much the more.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7215) (tudalen 032)

|

32

WELSH GRAMMAR

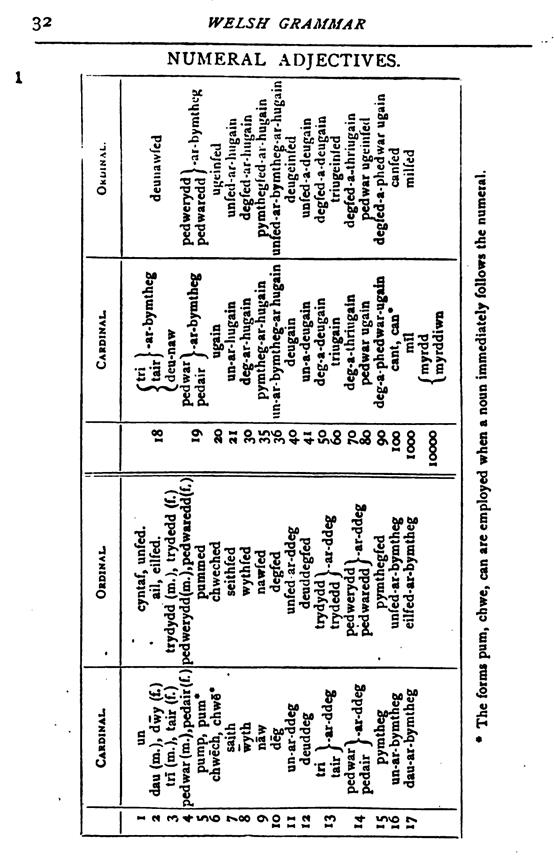

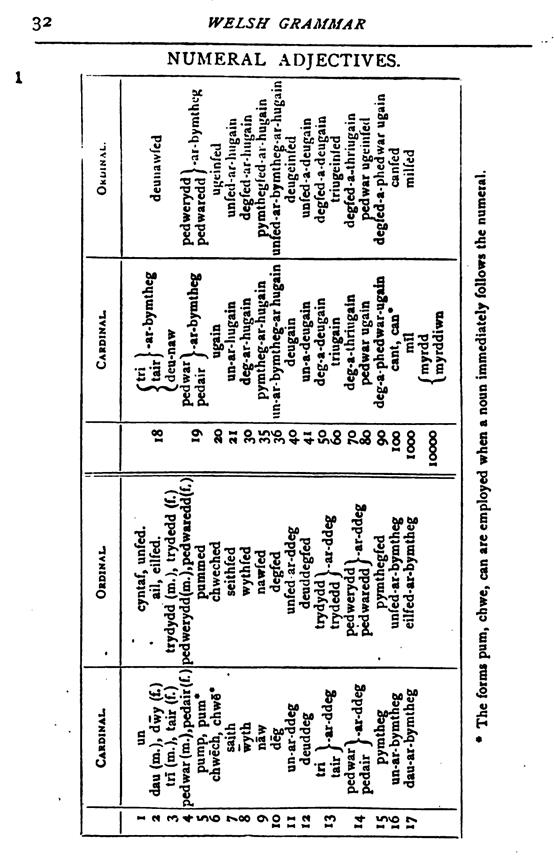

NUMERAL ADJECTIVES.

•

3 4 6

7 9 I0 II 12 t3 14 :g 17

T

CARDINAL

•

un pedwar (m.),pedair ) pump, pum* chwEch,

chwe* saith iiyth naw (Mg un-arecideg deuddeg

tri }-ar-ddeg taw' pedwar}eareddeg pedair pymtbeg

unear•bymtheg dau•arsbymtheg

•

•

ORDINAL.

cyntaf, unfed. ail, eilfed. trydydd (me),

trydedd (f.) pedwerydd(m.),pedwaredd(C) punned chweched seithfed wythfed

nawfed degfed unfedearmddeg deuddegfed trydydd) ee trydedd saredd pedwerydd f

ettraddeg pedwaredd pymthegfed unfed•arebymtheg eilfed•ar-bymtheg

•

18

19 20 21 30 35 36 40 41 50 60 80 90 I00 Iwo

10000

CARDINAL

ter dfilar •ar•bymthegeuenaw ped war}

earbymtb pedair

ugain uneareliugain degmar•hugain

pymthegear•hugain un•ar-bymthegear hugain deugain unsa-deugain deg•a•deugain

triugain deg•at•thriugain pedwar ugain deg•aephedwar•ugain cant, can* mil f

myrdd Imyrddiwn

OkbINAL.

deutiawkd

pedwerydd }earebymtheg pedwaredd ugtinfed

unied-arelltigain degfed-arelitigain pymthegied-arehugain unfed•ar-bymtheg•arehugain

deugeinfed unfedea•deugain degfedea•deugain triugeinied degfed•a-thriugain

pedwar ugeinied degkci•a•phed war ugain aided miffed

•

• The forms pum, chore, can are employed

when a noun immediately follows the numeral.

YVIVItrietYD liS7IM

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F7216) (tudalen 033)

|

ACCIDENCE

33

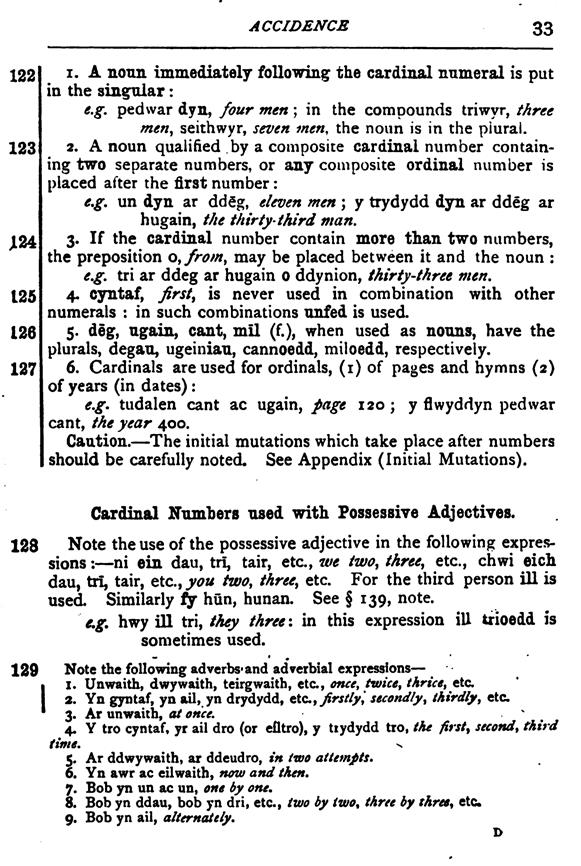

122

123

JL24

125 126 127

1. A noun immediately following the cardinal numeral is put in the singular:

e.g, pedwar dyn, four men; in the compounds triwyr, three men, seithwyr,

seven men, the noun is in the piural.

2. A noun qualified by a composite cardinal number containing two separate

numbers, or any composite ordinal number is placed after the first number:

e,g, un dyn ar ddgg, eleven men; y trydydd dyn ar ddeg ar hugain, t/ie

thirty- third man,

3. If the cardinal number contain more than two numbers, the preposition

Ojfrom, may be placed between it and the noun:

e,g, tri ar ddeg ar hugain ddynion, thirty-three men,

4. cyntaf, firsts is never used in combination with other numerals: in such

combinations unfed is used.

5. deg, ugain, cant, mil (f.), when used as nouns, have the plurals, degau,

ugeiniau, cannoedd, miloedd, respectively.

6. Cardinals are used for ordinals, (i) of pages and hymns (2) of years (in

dates):

e,g> tudalen cant ac ugain, page 120; y flwyddyn pedwar cant, the year

400.

Caution. — The initial mutations which take place after numbers should be

carefully noted. See Appendix (Initial Mutations).

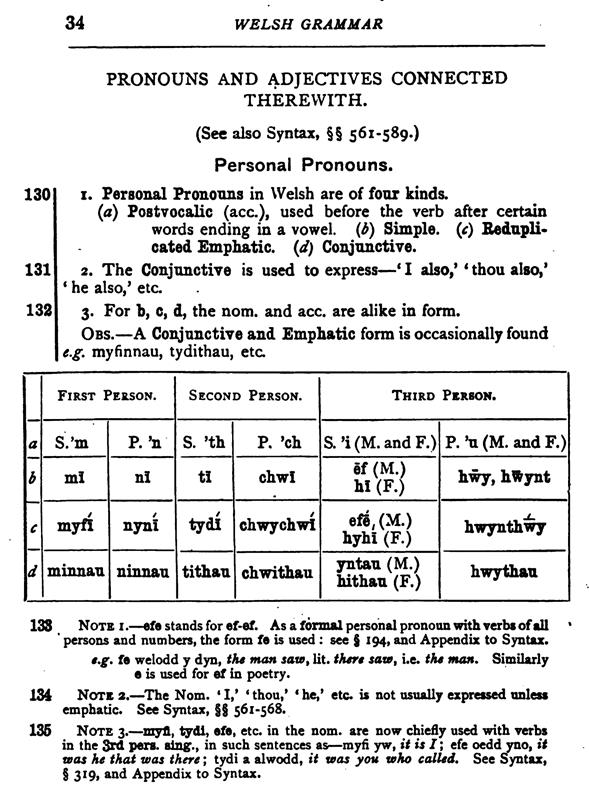

Cardinal Numhers used with Possessive Adjectives.

128 Note the use of the possessive adjective in the following expressions: —

ni ein dau, tri, tair, etc., we two, three, etc., chwi eich dau, tri, tair,

etc., you two, three, etc. For the third person ill is used. Similarly tj

hun, hunan. See § 139, note.

e.g. hwy ill tri, th three: in this expression ill trioedd is sometimes used.

129 Note the following adverbs* and adverbial expressions —

II. Unwaith, dwywaith, teirgwaith, etc, once twice, thrice, etc. 2. Yn

gyntaf, yn ail, yn drydydd, tic, firstly', secondly, thirdly, etc. 3. Ar

unwaith, at once.

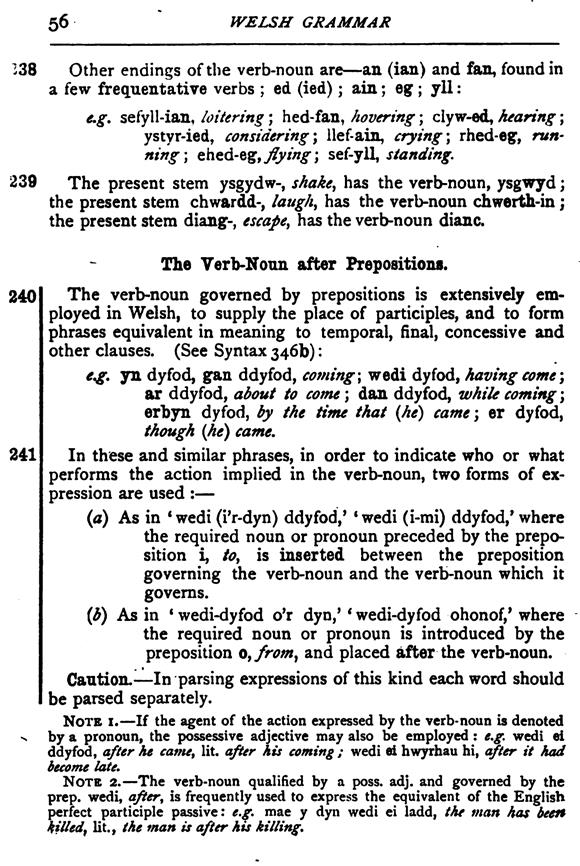

4. Y tro cyntaf, yr ail dro (or elltro), y tiydydd tro, the first, second,

third time. V

5. Ar ddwywaith, ar ddeudro, in two attempts.

6. Yn awr ac eilwaith, now and then.

7. Bob yn un ac un, one by one,

8. Bob yn ddau, bob yn dri, etc., two by two three by three, etc

9. Bob yn ail, alternaiely.

D

|

|

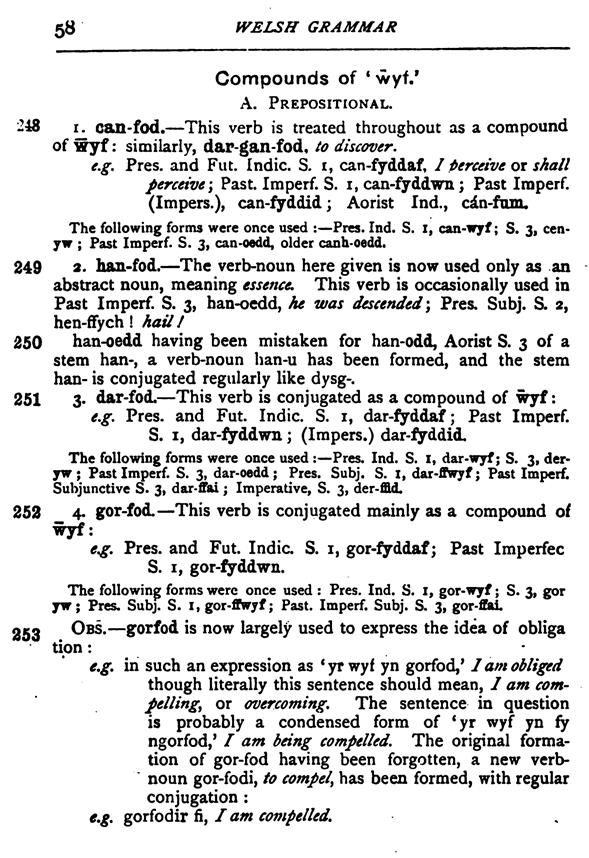

|

|

|

(delwedd F7217) (tudalen 034)

|

34

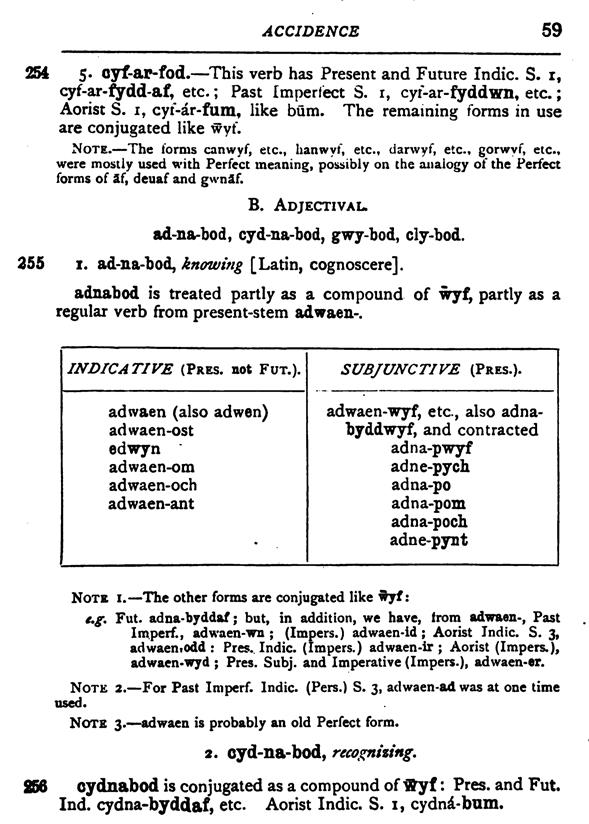

WELSH GRAMMAR

130

131 132

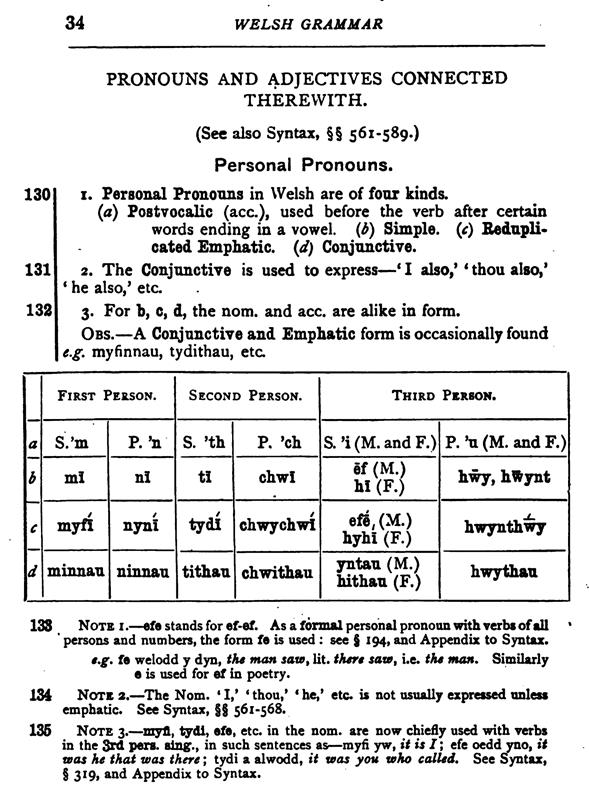

PRONOUNS AND ADJECTIVES CONNECTED

THEREWITH.

(See also Syntax, §§ 561-589.)

Personal Pronouns.

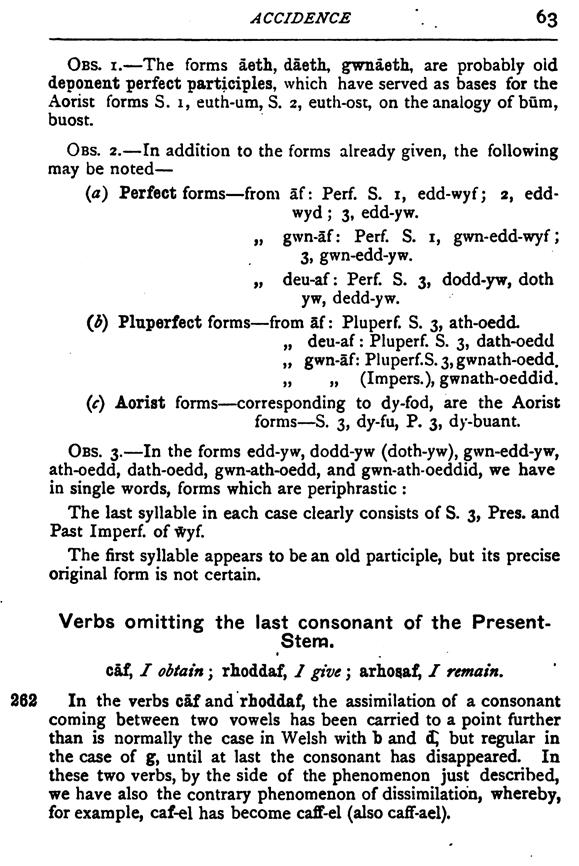

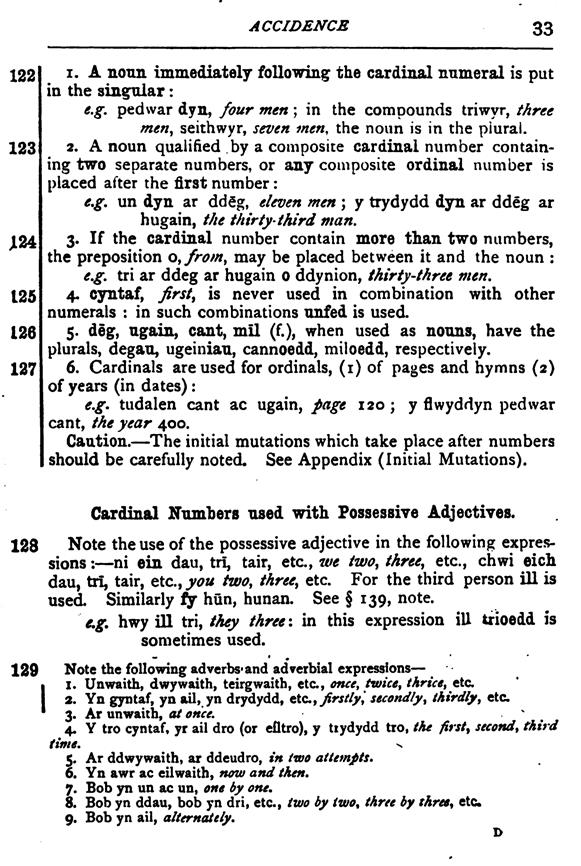

1. Personal Pronoxms in Welsh are of four kinds.

(a) Postvocalic (ace), used before the verb after certain words ending in a

vowel, (d) Simple. (£) BedupliGated Emphatic, {d) Conjunctive.

2. The Conjunctive is used to express — ' I also/ ' thou also,' * he also,'

etc.

3. For b, c, d, the nom. and ace. are alike in form.

Obs. — A Conjunctive and Emphatic form is occasionally found tf.. myfinnau,

tydithau, etc

First Person.

Second Person.

Third Person.

a b

c

d

S.'m

P. 'n

S. 'th

P. 'ch

S. 'i (M. and F.)

P. 'u (M. and F.)

mi

ni

ti

chwi

•

ef (M.) hi (F.)

hwy, hWynt

myfi

n3mi

tyd

chwychwi

efg,(M.) hyhi (F.)

hwynthwy

minnau

ninnau

tithau

chwithau

yntau (M.) hithau (F.)

hwythau

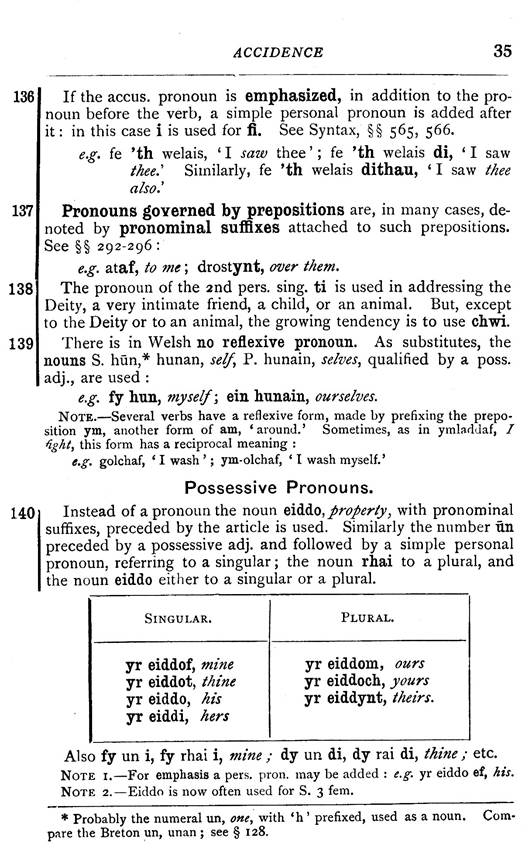

133 Note i .fe stands for ef-ef. As a formal personal pronoun with verbs of

all ' persons and numberSi the form fe is used: see § I94» and Appendix to

Syntax.

9,g, fe welodd y dyn, th$ man saw, lit. ihsrg saw, i.e. the man. Similarly 6

is used for ef in poetry.

134 Note 2. — The Nom. * 1/ * thou,' * he,' etc is not usually expressed unless

emphatic. See Syntax, §§ 561-568.

135 Note 3. — myfl, tydi, efe, etc. in the nom. are now chiefly used with

verbs in the 3rd pen. sing'., in such sentences as — myfi yw, it is I; efe