kimkat0277e. Dysgu Gwenhwyseg.

Learning the Gwentian dialect of Welsh.

14-08-2018

●

kimkat0001 Yr Hafan www.kimkat.org

●

● kimkat1864e Gateway to this Website in English / Y Fynedfa Saesneg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwefan/gwefan_arweinlen_2003e.htm

●

● ● kimkat2045k Welsh

dialects / Tafodieithoedd Cymru www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_cymraeg/cymraeg_tafodieitheg_gymraeg_mynegai_1385e.htm

● ● ● ● kimkat0934k Y Wenhwyseg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwenhwyseg/gwenhwyseg_cyfeirddalen_1004e.htm

● ● ● ● ● kimkat0277e Y Tudalen Hwn

|

|

Gwefan Cymru-Catalonia |

|

Learning Gwentian.

.....

To begin with, we give a rough approximation of where Gwentian is and was

spoken.

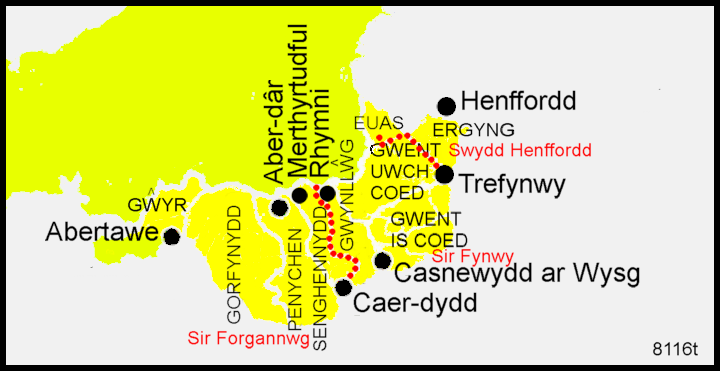

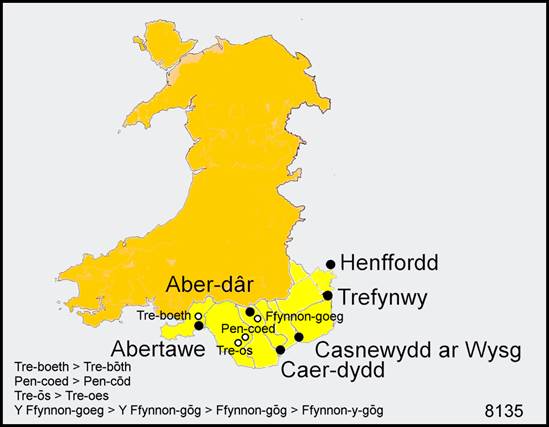

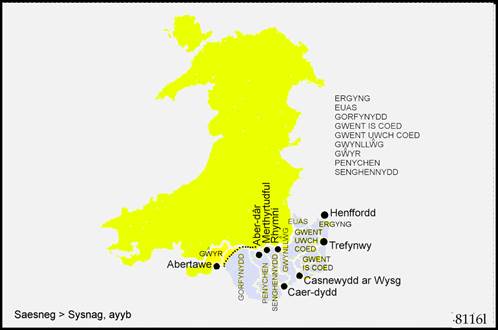

In the map below we represent conventionally the area of Gwentian speech as being the pre-1974 counties of Sir Forgannwg / Glamorganshire and Sir Fynwy / Monmouthshire, and two areas in western Herefordshire. This whole area corresponds to nine medieval commotes of Wales:

1/ Gŵyr

(English: Gower), Gorfynydd or Gwrinydd, Senghennydd (these three commotes

corresponding to the county of Sir Forgannwg / Glamorganshire formed in 1536),

2/ Gwynllŵg (English: Wentloog), Gwent Is Coed, Gwent Uwch Coed and

eastern Euas (English: Ewyas) which in 1536 became Sir Fynwy / Monmouthshire),

3/ and western Euas and Ergyng (English: Archenfield) transferred to Swydd

Henffordd / Herefordshire in England in 1536.

Welsh disappeared from Euas / Ergyng / Gwent Uwch Coed and Gwent Is Coed in the

1800s, but the dialect here was also Gwentian – that is, the same or little

different from the Welsh spoken to the west, in Gwynllŵg, Senghennydd,

Penychen, and Gorfynnydd.

(delwedd 8116t)

In the map above the dotted red line indicates the boundaries of the counties of Sir Forgannwg / Glamorganshire, Sir Fynwy / Monmouthshire, and Swydd Henfforff / Herefordshire.

We shall now look at a number of the features of its

pronunciation that are typical of Gwentian.

a/ Some features are common

throughout Wales in the spoken language.

b/ Many are general in South

Wales, and are common to the south-west and the south-east, but are not found

in the north.

c/ Some are found only in

south-eastern Wales, and are the distinctive characteristics of Gwentian.

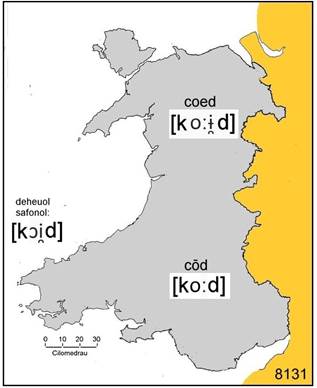

1/ The diphthong ‘oe’ in

monosyllables becomes a long ‘o’ (a feature common to South Wales) (coed >

cōd) (= wood)

2/ Long ‘a’ [a:] in

monosyllables becomes ɛ̄ [ɛ:]

in Gwentian (this sound in called in Welsh yr ‘a’ fain – English: the slender

’a’) (cath > cɛ̄th) (= cat)

3/ The diphthong ‘ae’ in

monosyllables becomes a long ‘a’ (a feature of south-west Wales and the western

fringe of the south-east Wales dialect or Gwentian)

(cael > câl) (= to get). In

Gwentian, this [a:] from a reeduced diphthong also becomes a narrow ‘e’ (câl > cɛ̄l).

4/ Half-long vowels in the penultimate syllable (tafod, gora, etc) (= tongue, best)

5/ Loss of a final [v] in

polysyllables (cyntaf > cynta) (= first)

6/ Palatalisation of s before or

after the vowel [i] (mis > mish) (= month)

.....

1

A feature common to all South

Wales:

1/

The diphthong ‘oe’ [ɔi̯] in monosyllables becomes a long

'o' [o:].

Here

we shall spell it as an 'o' with a macron, that is, ō.

(The usual way of representing this long ‘o’

from an original ‘oe’ – for example, in dialect writing - is either with an

apostrophe (co’d) (nowadays the

recommended form, as it is clear that it is a reduction of a diphthong), or

with a circumflex (côd).) (In

standard Welsh this is coed (= wood)

(and pronounced in southern standard Welsh as [kɔi̯d]).

(The standard South Wales

pronunciation ‘oe’ [ɔi̯] is

similar to the diphthong in English ‘oi’, ‘oy’ (coin, boy); the Northern

pronuncation however is a more distinctive: [o·ɨ̯] (first element a half-long

closed ‘o’ with a semi-consontal ‘i’ similar to a French ‘u’ (sud, mur, vaincu)

or German ü (Güter, hübsch)).

(ynganiad) deheuol safonol =

standard southern (pronunciation)

(delwedd 8131)

Here

are some examples:

coed [kɔi̯d] woodland >

cōd [ko:d]

moel [mɔi̯l] bald >

mōl [mo:l]

toes [tɔi̯s] dough >

tōs [to:s]

oed [ɔi̯d] age > ōd

[o:d]

soeg [sɔi̯g] dregs from

brewing, draff; pigswill > sōg [so:g]

poen [pɔi̯n] pain >

pōn [po:n]

poeth [pɔi̯θ] hot; burnt > pōth [po:θ]

oes [ɔi̯s] is > ōs

[o:s]

loes [lɔi̯s] anguish, mental

pain; agony, great physical pain > lōs [lo:s]

It is found in local pronunciations of place names - Pen-cōd (Pen-coed) (=

edge of the woodland), Tre-bōth (Tre-boeth) (= the burnt trêv or

farmstead)

Exercise 1: What are these words

in southern Welsh?

1.. moel (= bald) [mɔi̯l]

2.. coes (= leg) [kɔi̯s]

3.. ffynnon goeg (= empty well)

[ˡfənɔn

ˡgɔi̯g]

4.. oed (= age) [ɔi̯d]

5.. coed (= wood) [kɔi̯d]

6.. troed (= foot) [trɔi̯d]

7.. croes (= cross) [krɔi̯s]

8.. toes (= dough) [tɔi̯s]

9.. poeth (= hot) [pɔi̯θ]

10.. oedd (= was) [ɔi̯ð]

11... oer (= cold) [ɔi̯r]

12... noeth (= nude) [nɔi̯θ]

13.. croen (= skin) [krɔi̯n]

ANSWERS:

1.. moel (= bald) > mōl

[mo:l]

2.. coes (= leg) > cōs

[ko:s]

3.. ffynnon goeg (= empty well)

> ffynnon gōg

[ˡfənɔn

ˡgo:g]

4.. oed (= age) ōd

5.. coed (= wood) cōd

[ko:d]

6.. troed (= foot) trōd

[tro:d]

7.. croes (= cross) crōs

[kro:s]

8.. toes (= dough) tōs

[to:s]

9.. poeth (= hot) pōth [po:θ]

10.. oedd (= was) ōdd [o:ð]

11... oer (= cold) ōr [o:r]

In Irish ‘cold’ is fuar [fˠuəɾˠ],

as it is in Scottish Gaelic [fuəɾ], from an orginal uar. This was

later understood as being fhuar (same pronunciation, as ‘fh’ is silent in the

modern languages), a lenited form of a supposed fuar. In Gwentian, a similar

cases occurs – the word gōr (< goer) was in use, since some speakers had

taken ōr (< oer) to be a soft-mutated form, and ‘restored’ the ‘g’, as

if the original word had had an initial ‘g’.

12... noeth (= nude) nōth

[no:θ]

13.. croen (= skin) crōn

[kro:n]

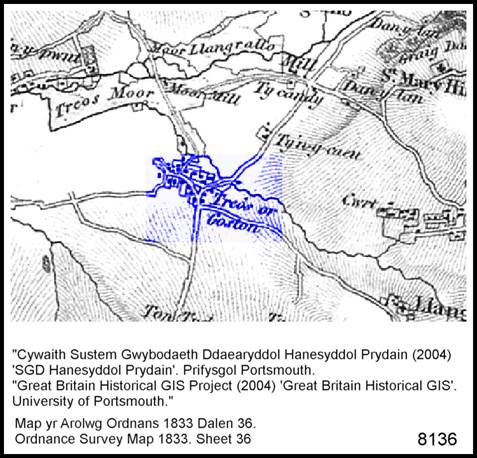

Note on Tre-oes:

(delwedd 8136)

Curiously, the village of Tre-os

[tre·ˡo:s] in

Bro Morgannwg has become Tre-oes [tre·ˡɔi̯s] in standard Welsh through

supposing that the element ‘os’ [o:s] was a localism for ‘oes’ (the Welsh name

is an adaptation – first known examples of the Weldh name are from 1600+ - of

the original English name for the farm, ‘Goston’ = the farmstead of the geese).

(The Ordnance Survey Map for1833

marks the place as ‘Treôs or Goston’ (quoted in Archif Melville Richards,

Prifysgol Bangor, online database).

A fuller explication by Gwynedd

Pierce (Notes on Place Namea. Goston: Tre-os.) is to be found here Morgannwg.

Transactions of the Glamorgan History Society. Volume XXVIII. 1984. Pages

84-87).

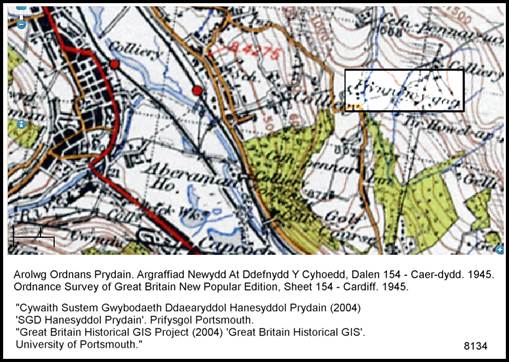

Note on Y Ffynnon Goeg:

(delwedd 8134)

This occurs as a place name and

the local form is often explained (erroneously) as being Ffynnon Gog (same

pronunciation - [ˡfənɔn

ˡgo:g])

as if from an original Ffynnon y Gog (‘the well of the cuckoo’). (The linking

definite article in place names is frequently omitted.)

This is seen in this example

below – a farm at Cefnpennar in Cwm Cynon – where the linking definite article

has been ‘restored’ (ffynnon gog > ffynnon y gog)

In 1570 this was ‘... y Fynon Goeg’, in 1600 ‘ffynnon

goge’

Information from Cynon Valley Place Names / Derick John. See a fuller explanation of this name see Derick John’s place-names website: http://someplacenamesinsouthwales.mysite.com/contact.html

The locations of Pen-coed,

Tre-boeth, Tre-os and Y Ffynnon-goeg:

(delwedd 8135)

(Note that in the rules for the

correct spelling of place names settlement names (houses, farms, villages, etc)

are spelt as a single word. So Pen y Coed or Pen Coed refers to a geographical

feature (the linking definite article in place names is frequently omitted).

But Pen-y-coed or Pen-coed is a settlement at this place.

Y Ffynnon Goeg refers to a well,

and Y Ffynnon-goeg refers to a settlement named after this .

An accented monosyllable in

settlement names is almost always preceded by a hyphen (some exceptions occur).

Thus not Pencoed (wnich suggests

Péncoed) or Penycoed (which suggests Penýcoed), but Pen-coed, Pen-y-coed (i.e.

suggesting Pen-cóed, Pen-y-cóed).

2

2/ The ‘slender a’.

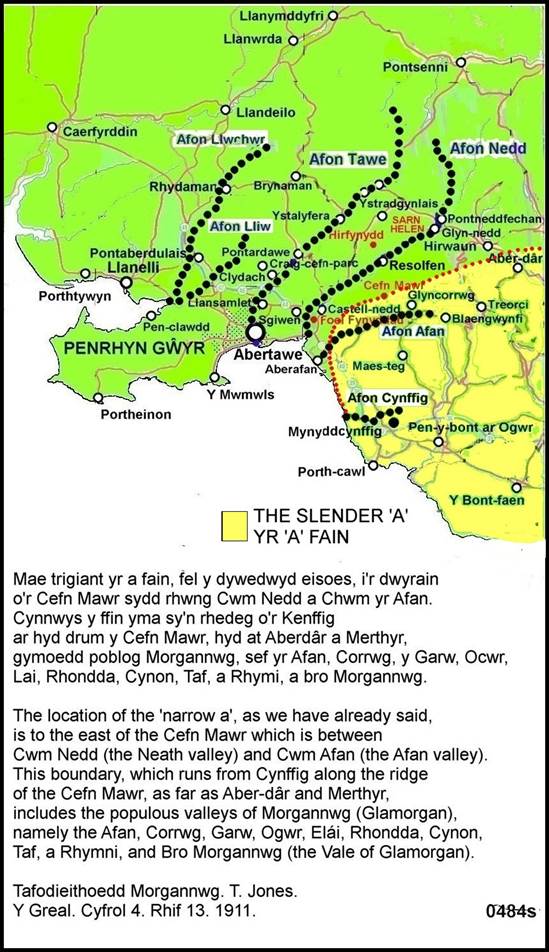

This is held to be the defining characteristic of ‘Y Wenhwyseg’. On the map below the area in which it is general is marked as yellow. The Afan Valley is regarded as the western limit – here or a little west beyond the valley this feature disappears. (For some, the dialect without the slender a is no longer ‘Gwentian’, though other Gwentian features occur further west, in the Tawe Valley and beyond).

The name ‘slender a’ is a translation of its Welsh name ‘a fain’ [‘a: vain].

A long ‘a’ [a:] in a monosyllable has become a long open ‘e’ of sorts in Gwentian (depending on the region of Gwent and Morgannwg).

We shall represent it as ɛ̄

in Gwentian orthography and as [ɛ:] in

the International Phonetic Alphabet.

(Atlthough some linguits use ɛ̄, most use the letter ‘ash’ – æ – to indicate the slender ‘a’. The symbol ɛ̄ though has the advantage of suggesting an open ‘e’ sound, which is a long vowel; and is easier to write (though it has the same inconvenience as æ when using a keyboard to type electroninc text – not all fonts recognise them, and they have to be added from the symbols option).

Thus we have in south-east Wales, in Gwent and Morgannwg, tân > tɛ̄n (fire), bach > bɛ̄ch (little), mab > mɛ̄b (son).

(delwedd 0484s)

AS we have menyioned, in west Glamorgan this feature is generally absent -

beyond the river Afan the original long ā is retained.

It is also known in mid-Wales. In both cases it seems to be a feature that has been adopted from English, where from around 1400 onwards the long ‘a’ [a:] eventually became the diphthong ‘ei’ [ei] of modern English (plate: pla:t > ple:t > pleit, face: fa:s > fe:s > feis, name: na:m > ne:m > neim, etc).

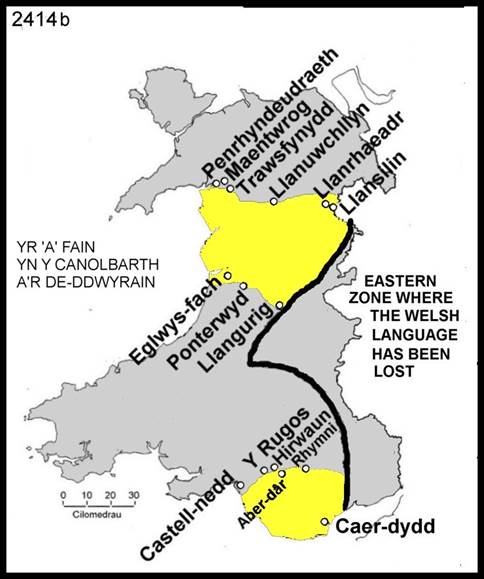

(delwedd 8166s)

This – in orange -

is possibly the historical extent of the narrow ‘a’ – there is place-name

evidence in eastern Gwent; Euas and Ergyng though are doubtful. Little is known

of the Welsh spoken there, though there were native Welsh speakers in the 1800s

and possibly into the early 1900s.

Below, the region of mid-Wales

where a ‘narrow a’ is in use.

(delwedd 2414b)

3

3/ The diphthong ‘ae’ in

monosyllables (south-west Wales examples)

The diphthong ‘ae’ [ai̯] in

monosyllables becomes a long 'a' [a:] in the south-west.

Here we shall spell it as an 'a'

with a macron: ā.

(The usual way of representing this long ‘a’ from an original ‘ae’ is either with an apostrophe (tra’d) (nowadays the recommended form, as it is clear that it is a reduction of a diphthong), or with a circumflex (trâd). (In standard Welsh, southern pronunciation, traed [trai̯d] = feet).

Here are some examples:

cael [kai̯l] to get > cāl

[ka:l]

gwaed [gwai̯d] blood > gwād

[gwa:d]

gwaeth [gwai̯θ] worse

> gwāth

[gwa:θ]

traeth [trai̯θ] beach

> trāth

[tra:θ]

traed [trai̯d] feet > trād

[tra:d]

Exercise 2

How are these pronounced in south-western Welsh?

1 blaen [blai̯n]

top; point; front side

2 cae [kai̯] field

3 Y Gaer [ә ˡgai̯r] (place name; the Roman fort; the British hillfort)

4 graen [grai̯n] grain (of wood);

excellence

5 gwaed [gwai̯d] blood

6 i maes [i ˡmai̯s] outside

7 llaeth [ɬai̯θ]

milk

8 saer [sai̯r] carpenter

9 traed [trai̯d] feet

10 ymlaen [әˡmlai̯n] forward (= from the preposition yn = in,

and the noun blaen = top; point;

front side)

ANSWERS:

1 blaen [blai̯n] top; point; front side blān [bla:n]

2 cae [kai̯] field cā [ka:]

3 Y Gaer [ә ˡgai̯r] (place name; the Roman fort; the British hillfort) Y Gār [ә ˡga:r]

4 graen [grai̯n] grain (of wood);

excellence grān [gra:n]

5 gwaed [gwai̯d] blood gwād

[gwa:d]

6 i maes [i ˡmai̯s] outside mās [ma:s] (th preposition ‘i’ is dropped

colloquially)

7 llaeth [ɬai̯θ]

milk llāth [ɬa:θ]

8 saer [sai̯r] carpenter

sār [sa:r]

9 traed [trai̯d] feet trād

[tra:d]

10 ymlaen [әˡmlai̯n] forward (= from the preposition yn = in,

and the noun blaen = top; point;

front side) ‘mlān [mla:n] (the initial syllable is dropped)

(delwedd 8137)

Examples of ɛ̄

in central and eastern Gwentian:

|

Standard Welsh |

South-western Welsh and western Gwentian |

Central and eastern Gwentian |

|

Aber-dâr [aberˡda:r] (< Aber-daer) town name, Aberdare in English |

Aber-dâr [aberˡda:r] |

Aber-dɛ̄r [aberˡdɛ:r], Byr--dɛ̄r [bərˡdɛ:r] |

|

aeth [ai̯θ] milk |

llāth [lla:θ] |

llɛ̄th [llɛ:θ] |

|

bach [ba:x] little |

bach [ba:x] |

bɛ̄ch [bɛ:x] |

|

blaen [blai̯n] top, point |

blān [bla:n] |

blɛ̄n [blɛ:n] |

|

cae [kai̯] field |

cā [ka:] |

cɛ̄ [kɛ:] |

|

da [da:] good |

da [da:] |

dɛ̄ [dɛ:] |

|

glas [gla:s] green, blue |

glas [gla:s] |

glɛ̄s [glɛ:s] |

|

graen [grai̯n] grain (of wood); excellence |

grān [gra:n] |

grɛ̄n [grɛ:n] |

|

gwaed [gwai̯d] blood |

gwād [gwa:d] |

gwɛ̄d [gwɛ:d] |

|

i maes [i ˡmai̯s] outside |

mās [ma:s] |

mɛ̄s [mɛ:s] |

|

llaeth [ɬai̯θ] milk |

llāth [ɬa:θ] |

llɛ̄th [ɬɛ:θ] |

|

mâb [ma:b] son |

māb [ma:b] |

mɛ̄b [mɛ:b] |

|

mân [ma:n] small, little |

mān [ma:n] |

mɛ̄n [mɛ:n] |

|

saer [sai̯r] carpenter |

sār [sa:r] |

sɛ̄r [sɛ:r] |

|

tân [ta:n] fire |

tân [ta:n] |

tɛ̄n [tɛ:n] |

|

traed [trai̯d] feet |

trād [tra:d] |

trɛ̄d [trɛ:d] |

|

Y Gaer [ә ˡgai̯r] (place name; the Roman fort; the British hillfort) |

Y Gār [ә ˡga:r] |

Y Gɛ̄r [ә ˡgɛ:r] |

|

ymlaen [әˡmlai̯n] forward; (= ym

+ blaen) |

’mlān [mla:n] |

’mlɛ̄n [mlɛ:n] |

Exercise 3

What are these words in Gwentian

pronunication?

1 gwnaeth [gwnai̯θ] he / she / it made or did

2 baedd [bai̯ð] boar

3 cae [kai̯] field, enclosure

4 cael [kai̯l] to get

5 daeth [dai̯θ] he / she / it came

5 llaeth [ɬai̯θ] milk

6 brân [bra:n] crow; jackdaw

7 saeth [sai̯θ] arrow

8 maes [mai̯s] open field

9 plas [pla:s] mansion, hall

10 maen [mai̯n] bakestone

11 daer [dai̯r] a variant of daear [dəi̯ar] earth

12 mae [mai̯] is, there is

ANSWERS

1 gwnaeth [gwnai̯θ] he / she / it made or did nɛ̄th [nɛ:θ]

2 baedd [bai̯ð] boar

bɛ̄ð [bɛ:ð]

3 cae [kai̯] field, enclosurec

[kɛ:]

4 cael [kai̯l] to get cɛ̄l

[kɛ:l]

5 daeth [dai̯θ] he / she / it

came dɛ̄th [dɛ:θ]

5 llaeth [ɬai̯θ] milk llɛ̄th

[ɬɛ:θ]

6 brân [bra:n] crow; jackdaw bra:n

[brɛ:n]

7 saeth [sai̯θ] arrow sɛ̄θ

[sɛ:θ]

8 maes [mai̯s] open field mɛ̄s

[mɛ:s]

9 plas [pla:s] mansion, hall pla:s

[plɛ:s]

10 maen [mai̯n] bakestone mɛ̄n

[mɛ:n]

11 daer [dai̯r] a variant of daear [dəi̯ar]

earth dɛ̄r

[dɛ:r]

12 mae [mai̯] is, there is mɛ̄

[mɛ:]

I’W GYWIRO

4

Half-long vowels

In South Wales the vowel in the accented syllable of a word is

generally half-long. It seems that this was formerly the situation in Northern

Welsh even in the 1800s but there half-long vowels have by now disappeared,

replaced by short vowels.

The vowels are a,e,i,o,u,w hence [a·, e·, i·, o·, i·, u·] – but not y

[ə], which is always short.

The rule is that a vowel is half-long before certain single consonants

(b, ch, d, dd, f, ff, g, l, n, r, th).

Here are examples in standard

Welsh with a south-western pronunciation (we have indicated the half-long vowel

with a mid-line dot, as in the IPA):

be·ddau [ˡbe·]

cre·du [ˡkre·d]

ca·nu [ˡka·n] (= to sing)

do·di [ˡdo·] (= to put)

a·ros [ˡa·rs] (= to stay)

There are exceptions – tthe vowel is short and not half-long in the following cases:

a/ The vowel y.

mynydd (= upland pasture; mountain) []

.....

b/ vowels before the consonants c, ng, j, m, p, s, sh, t, tsh,

mamau (= mothers) (before m)

llongau (= ships) (before ng)

.....

c/ vowels before doubled consonants:

annwyl (= dear) (doubled consonant)

ennill (= to win) (doubled consonant)

.....

d/ vowels before doubled consonants:

estyn (= to extend) (consonant cluster)

darllen (= to read) (consonant cluster)

.....

d/ Many loanwords from English have a short vowel as in English, and

are not adapted to the Welsh system: brago [ˡbragɔ] (= to brag, boast)

(i.e. not [ˡbra·gɔ])

.....

e/ a single l in modern orthography might

represent an old geminated l. There is no way of knowing this from the

spelling.

(A single ‘l’ which was

historically geminated is to be found too in Catalan – and there is a special

letter for this: l·l, although nowadays it is pronounced as a single ‘l’ and the

etymological spelling is , technically speaking, unnecessary).

Calon (heart) has a short vowel

.....

f/ the ‘l’ might have formed part of a consonant cluster - ’ala (send;

spend) (originally *halgha) (an indicative spelling – this actual spelling was not

used historically). This has a short vowel too.

.....

5

.....

A common feature in spoken Welsh is the loss of a final [v] (spelt

‘f’) in polysyllables. The standard written language maintains this [v]. (A

final -f is to be seen especially in the superlative ending -af, and in

compounds based on ‘tref’ = homestead).

(Some exceptions to a final ‘f’ retained in standard Welsh – ‘beer’

was originally cw·rwf [], now always cw·rw [])

cyntaf [] (= first) > cynta

pentref

hendref

adref

gartref

lleiaf

araf

am,laf

nesa

6

.....

6/ Palatalisation of 's' before or after the

vowel 'i'.

.....

palatalisation of 's' before or

after the vowel 'i'. In other words, s [s] becomes sh [ʃ].

mis [mi:s] month mish [mi:ʃ]

llais [ɬaɪs] voice

llaish [laɪʃ]

siglo [sɪglɔ] to shake shiglo [ʃsɪglɔ]

In standard Welsh words taken from English which had an original 'sh'

are spelt in Welsh with 'si'. The 'si' [sj] represents a northern

pronunciation. Northern Welsh-speakers were unable to imitate this foreign

sound [ʃ], although from around 1900 onwards (to give a very rough

indication) , through the imposition of English as a universal second language,

and the subsequent bilingualism, the sound is no longer alien to Northerners.

In dialect writing it is spelt 'sh' in order to avoid the ambiguity

which the spelling 'si' produces (it might be [si̯] (s + semi-consonant)

as in ‘siop’, or ‘s’ + the vowel ‘i’ [sɪ, si·, si:]

spesial > speshal (= special)

pinsio > pinsho (= to pinch)

sosiashwn (< association)

Siop, representing an older (northern) pronunciation [si̯ɔp], but now generally [ʃɔp], English: shop, is spelt shop [ʃɔp] in Gwentian

simnai [ˡsimnaɪ] chimney

is shimla [ˡʃɪmla] in Gwentian.

sidan [ˡsi·dan] is shitan [ˡʃi·tan]

in Gwentian

(delwedd 8132)

Similarly, at the end of a word, 'sh' [ʃ]

in words borrowed from English became simply 's' [s] at the end of a

word. Standard spelling maintains this, although speakers even in the north

probably use 'sh' nowadays.

starts starch startsh

pits pitch, tar pitsh

Exercise 2: What are these words in southern Welsh? (The answers are

not so predictble as other sound changes also take place, which we will examine

later)

1.. ceisio (= to try)

2.. Lleisan (= forename: from llais = voice, -an diminutive suffix)

3.. piso (= to piss)

4.. meistres (= mistress)

5.. eisingrug (= pile of chaff)

6.. eisiau (= need)

7.. sir (= county)

8.. eistedd (= to sit)

9.. yr un sut â (= like, literally ‘the same kind as, the same

likeness as)

10.. gwisgo (= to wear)

11.. isel (= low)

ANSWERS:

1.. ceisio (= to try) cisho

2.. Lleisan (= forename: from llais = voice, -an diminutive suffix)

Lleishon (also as a surname current in Glamorgan; Anglicised as Leyshon)

3.. piso (= to piss) pisho

4.. meistres (= mistress) mishtras

5.. eisingrug (= pile of chaff) shingrig

6.. eisiau (= need) isha

7.. sir (= county) shir

8.. eistedd (= to sit) ishta

9.. yr un sut â (= like, literally ‘the same kind as, the same

likeness as) ishta

10.. gwisgo (= to wear) gwishgo

11.. isel (= low) ishal

7

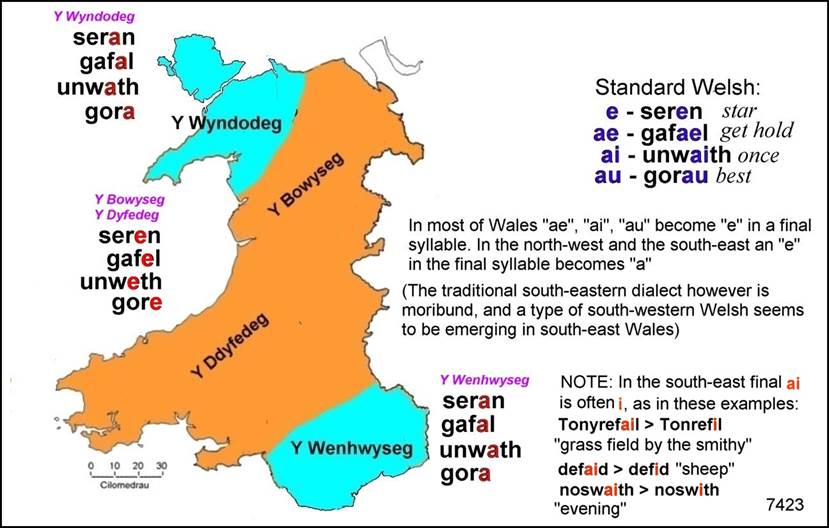

3/ Final-syllable ‘a’ equivalent to the ‘e’

in general colloquial Welsh (south-western, midland, north-eastern)

Final-syllable ‘e’

In both north-western and south-eastern Welsh this becomes ‘a’

seren star seran

8

In spoken Welsh, final-syllable diphthongs ‘ae, ai, au’ all become ‘e’.

gafael get hold of > gafel

cadair chair > cader

pethau things > pethe

As with original 'e', in north-west Wales and south-east Wales this is realised

as [a].

gafael get hold of > gefal

cadiar chair > catar

pethau things > petha

(delwedd 7423)

(delwedd 8116l)

This blue area is where the fianl

‘a’ exists or existed. (The map shows its presumed occurrence too in Euas and

Ergyng when Welsh was spoken there, though this needs to be confirmed.).

9

Absence of the semi-consonant [j] or [i̯] (two symbols

representing the same sound – in some studies the first will be found, in

others, the second)

.....

This is to be seen especially with the plural suffixes -iau and ion,

and the verbal suffix -io (above all. These are the standard forms, and also

the northern forms; in the south they become -au (colloquially -e in the

south-west and a in the south-east), -on and -o.

....

gwaith (= work), gweithiau (= works; also in the sense of ironworks,

mines, factories, etc), south-western gweithe, Gwentian: gwitha (Y Gweithe, Y

Gwitha is the name for the industrial valleys of the south-east, but originally

the ironworks at the heads of the valleys)

.....

In loan words from English (not admitted in literaty Welsh, but common

colloquially), the ending -io is usd in the North, and -o in the south

.....

cochion (= red, plural form) > cochon (southern)

gobeithio (= to hope), gobitho (southern)

.....

The ending -io (northern; also standard Welsh) (-o in Southern Welsh)

is a productive suffix from which verbs can be created, often base on English

verbs.

Thus English Google, from which a verb has been formed ‘to google’;

Welsh gwglio, gwglo.

.....

Many such loan words in Welsh which have come from English go back

some centuries and are not recent additions to the language.

to join: Northern: joinio (used by Edward Lhuyd c.1700), Southern:

joino

to shine: Northern: sheinio, Southern: sheino

to claim: (first known example in the 1300s) Northern: cleimio,

Southern cleimo.

to build: (first known example in the 1600s) Northern: bildio,

Southern bildo.

.....

Exercise 1. What are these words in Gwentian?

1.. to dress, adorn

2.. to kick

3.. to build

4... to act

5... to labour

6.. to vex

7... to lodge

8.. to clap (= applaud; to pat (somebody on the back))

9.. to brag

10... to smash

ANSWERS (the dates indicate when century in which the first known

example appears in Welsh)

1.. to dress, adorn (1800+) dreso [ˡdrsɔ]

2.. to kick (1700+) cico [ˡkkɔ]

3.. to build (1500+) bildo [ˡbldɔ]

4... to act (1700+) acto [ˡaktɔ]

5... to labour (1500+) labro [ˡlabrɔ]

6.. to vex (1700+) becso [ˡbcsɔ]

7... to lodge (1500+) lojo [ˡlɔɔ]

8.. to clap (= applaud; to pat (somebody on the back)) (1600+) clapo [ˡklapɔ]

9.. to brag (1500+) brago [ˡbragɔ]

10... to smash (?1800+) smasho [ˡsmaʃɔ]

(Northern dresio, cicio, bildio, actio, labrio, becsio, lojio, clapio,

bragio, smashio)

10

13/ Provection.

dagrau (= tears) > dagre (South-west), dacra (= south-east)

11

8/ tonic ei > i

Gobeithio > gobitho (= to hope)

12

Final wy

ofnadwy > ofnatw (= awful)

13

Final oe > o

Llynoedd > llyno’dd (= lakes)

12

9/ epenthetic vowel

aml > amal (= often)

13

14/ The missing ‘h’.

hala > ala (

14

AMRYW

Cōd-di·on (Coed-duon / Blackwood),

cre·ti (= to believe) (standard: credu)

blo·ta (= flowers) (standard: blodau)

A long ‘a’ might be original (as in tân = fire, bach = small, mab = son), or the reduced diphthong ‘ae’ which is long ‘ā in the south-west.

.......................................

Sumbolau:

a A / æ Æ / e E / ɛ Ɛ / i I / o O / u U / w W / y Y /

MACRON: ā Ā / ǣ Ǣ / ē Ē / ɛ̄ Ɛ̄ / ī Ī / ō Ō / ū Ū / w̄ W̄ / ȳ Ȳ /

BREF: ă Ă / ĕ Ĕ / ĭ Ĭ

/ ŏ Ŏ / ŭ Ŭ / B5236: ![]() B5237:

B5237: ![]()

BREF

GWRTHDRO ISOD: i̯, u̯

CROMFACHAU: ⟨ ⟩ deiamwnt

ˡ ɑ ɑˑ aˑ a: / æ æ: / e eˑe: / ɛ ɛ: / ɪ

iˑ i: / ɔ oˑ o: / ʊ uˑ u: / ə ø / ʌ /

ẅ Ẅ / ẃ Ẃ / ẁ Ẁ / ŵ Ŵ /

ŷ Ŷ / ỳ Ỳ / ý Ý / ɥ

ˡ ð ɬ ŋ ʃ ʧ θ ʒ ʤ / aɪ ɔɪ

əɪ uɪ ɪʊ aʊ ɛʊ əʊ / £

ә ʌ ẃ ă ĕ ĭ ŏ ŭ ẅ ẃ ẁ Ẁ ŵ ŷ ỳ Ỳ

Hungarumlaut: A̋ a̋

wikipedia, scriptsource. org

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ǣ

---------------------------------------

Y TUDALEN HWN /THIS PAGE / AQUESTA PÀGINA:

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwenhwyseg/dysgu-gwenhwyseg-01_0277e.htm

---------------------------------------

Creuwyd / Created / Creada: 31-05-2017

Adolygiadau diweddaraf / Latest updates / Darreres actualitzacions: 31-05-2017

Delweddau / Imatges / Images:

Ffynhonnell

/ Font / Source:

|

Freefind. |

Ble'r wyf i? Yr ych chi'n ymwéld ag un o dudalennau'r Wefan CYMRU-CATALONIA

On sóc? Esteu visitant una pàgina de la Web CYMRU-CATALONIA (=

Gal·les-Catalunya)

Where am I? You are visiting a page from the CYMRU-CATALONIA (=

Wales-Catalonia) Website

Weə-r äm ai? Yüu äa-r víziting ə peij fröm dhə CYMRU-CATALONIA

(= Weilz-Katəlóuniə) Wébsait

savage or surly person dog o ddyn gweler gpc

peiryn (NE GLAM= spit

Poer y gwcw or peiryn y gww