10-12-2021 19-00

● kimkat0001 Yr Hafan www.kimkat.org

● ● kimkat2001k Y Fynedfa Gymraeg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwefan/gwefan_arweinlen_2001k.htm

● ● ● kimkat2045k Tafodieithoedd Cymru www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_cymraeg/cymraeg_tafodieitheg_gymraeg_mynegai_2045k.htm

●

● ● ● kimkat0934k Y Wenhwyseg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwenhwyseg/gwenhwyseg_cyfeirddalen_0934k.htm

●

● ● ● ● kimkat0959e Y tudalen hwn

|

|

Gwefan Cymru-Catalonia |

|

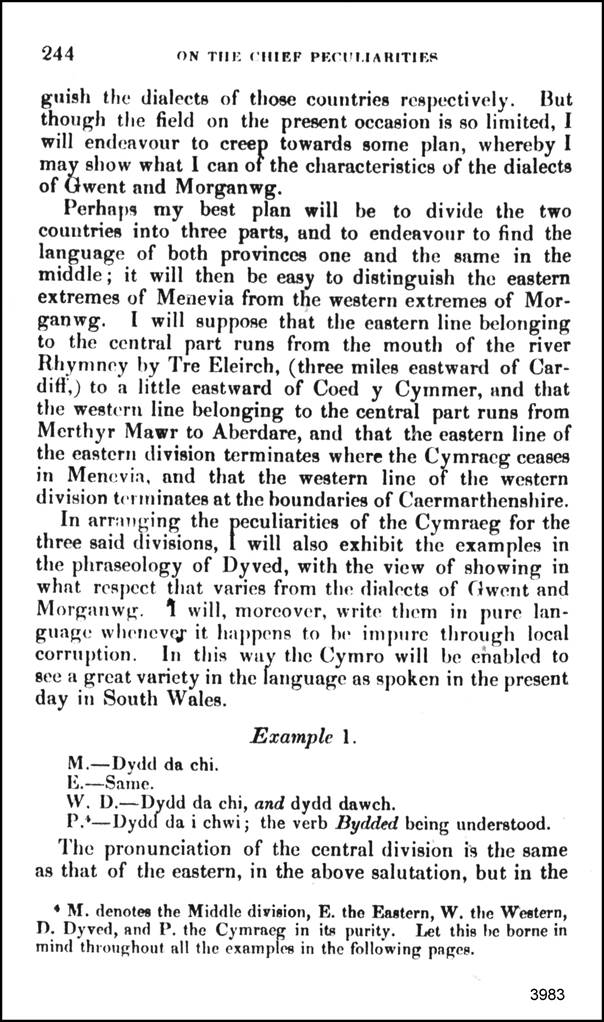

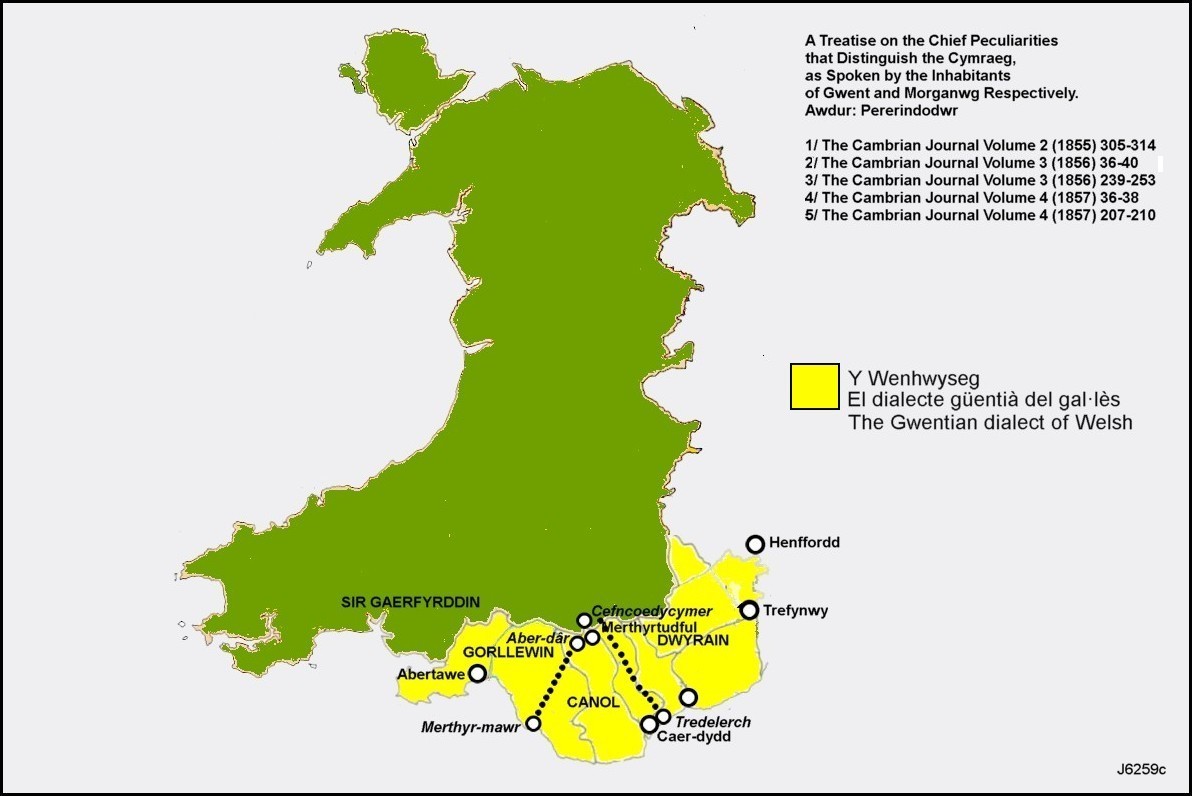

A

Treatise on the Chief Peculiarities that Distinguish the Cymraeg, as Spoken by

the Inhabitants of Gwent and Morganwg Respectively.

Awdur: Pererindodwr

1/ The Cambrian Journal Volume 2 (1855) 305-314

27 The Cambrian Journal Volume 3 (1856) 36-40

3/ The Cambrian Journal Volume 3 (1856) 239-253

4/ The Cambrian Journal Volume 4 (1857) 36-38

5/ The Cambrian Journal Volume 4 (1857) 207-210

(delwedd J6259c)

Tair rhan y Wenhwyseg (Dwyrain / Canol /

Gorllewin) yn ôl yr erthygl hon / three zones of Gwentian (East, Middle, West)

according to this article.

(Additions or my comments in

brackets and orange letters. Some typing mistakes yet to be hunted down and

eliminated. The spelling in English and Welsh is the same as in the original)

(We have omitted the

text at the beginning of this section - three pages - remarks on the eisteddfod

tradition in Morgannwg).

(Note: (1) in the lists

of examples below, where the original has ‘same’, I have repeated the phrase.

(2) After the initials representing the zones that Pererindodwr has delineated,

I have added a indication of the zone for clarity’s sake. For example, the

author has simply “E.”, but I have added (East = the area east of the Rhymni river)

(3) In addition, I have altered slightly his order of zones in the examples,

which in the original is M / E / W / D / P. (Middle, Eastern, Western, Dyved,

Pure). I have placed E first to make a more logical continuum from east to west

- E / M / W / D / P.)

(delwedd J6260)

____________________________________________

The Cambrian Journal, Volume 3, 1856, pp305-314

|

|

|

|

|

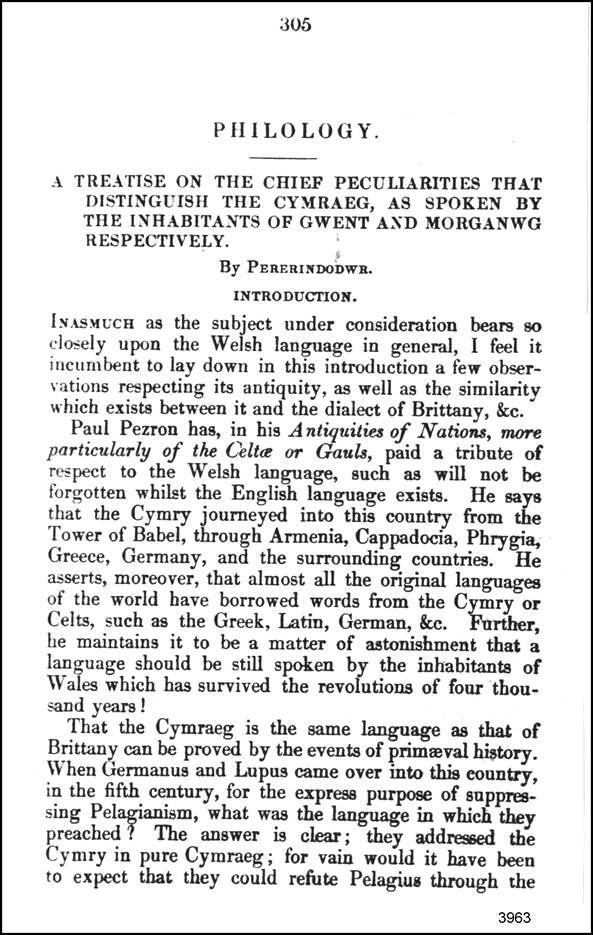

305. PHILOLOGY. A TREATISE ON THE CHIEF PECULIARITIES THAT DISTINGUISH THE CYMRAEG,

AS SPOKEN BY THE INHABITANTS OF GWENT AND MORGANWG RESPECTIVELY. BY PERERINDODWR INTRODUCTION Inasmuch as the subject under consideration bears so closely upon the

Welsh language in general, I feel it incumbent to lay down in this

introduction a few observations respecting its antiquity, as well as the

similarity which exists between it and the dialect of Brittany, &c. under

consideration bears so closely upon the Welsh language in general, I feel it

incumbent to lay down in this introduction a few obser- vations respecting

its antiquity, as well as the similarity which exists between it and the

dialect of Brittany, &c. Paul Pezron has, in his Antiquities of Nations, more particularly of

the Celtæ or Gauls, paid a tribute of respect to the Welsh language, such as

will not be forgotten whilst the English language exists. He says that the

Cymry journeyed into this country from the Tower of Babel, through Armenia,

Cappadocia, Phrygia; Greece, Germany, and the surrounding countries. He

asserts, moreover, that almost all the original languages of the world have

borrowed words from the Cymry or Celts, such as the Greek, Latin, German,

&c. Further, he maintains it to be a matter of astonishment that a

language should be still spoken by the inhabitants of Wates which has

survived the revolutions of four thousand years ! That the Cymraeg is the same language as that of Brittany can be

proved by the events of primæval history. When Germanus and Lupus came over

into this country, in the fifth century, for the express purpose of

suppressing Pelagianism, what was the language in which they preached? The

answer is clear; they addressed the Cymry in pure Cymraeg; for vain would it

have been to expect that they could refute Pelagius through the |

|

|

|

|

|

PHILOLOGY. 306. medium of a translation; vain would it have been to preach to the Cymry

in Latin or Gallic. Reason used to perform its functions in those early days,

as well as now, and the Cymry, even then, knew how useless it would be to

talk Greek with a Briton, or Cymraeg with a Grecian. Another thing which

proves this is the fact that the relatives of many of the Cymry dwelt

formerly in Brittany. There it was that Emyr Llydaw lived, and to him

probably went Teilo from Llandaff, when the yellow fever raged in this

country. Thither also went Eudaf, after the death of Teilo, when Prince

Cadwgan quarreled with him on a matter touching the archiepiscopal rights and

dignity. Thus we find that at that early period there existed an intercourse

between the people of this country and the Armoricans, and, in confirmation

of the same truth, might be adduced the histories of Cadwaladr, Rhys ab

Tewdwr, and others. but there can be no doubt that they were originally the

same nation, and possessed a common language; and this fact can be further

corroborated by the present similarity which exists between the two dialects.

And here, ere I leave the subject in question, I shall lay down some few

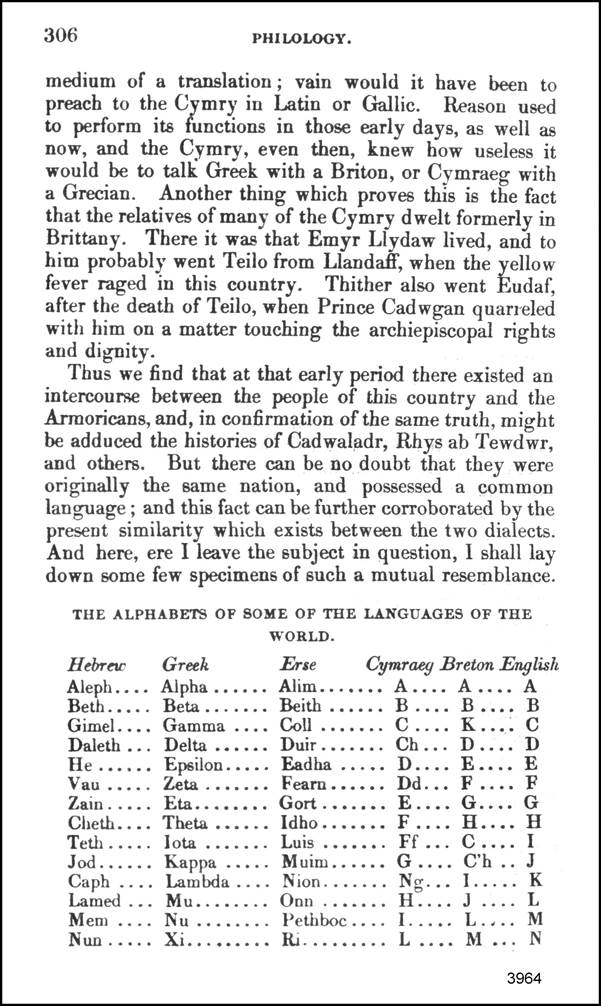

specimens of such a mutual resemblance. THE ALPHABETS OF SOME OF THE LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD. . Hebrew Aleph, Beth, Gimel, Daleth, He, Vau, Zain, Cheth, Teth, Jod,

Caph, Lamed, Mem, Nun Greek Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, Theta, Iota,

Kappa, Lambda, Mu, Nu, Xi Erse Alim, Beith, Coll, Duir, Eadha, Fearn, Gort, Idho, Luis, Muim,

Nion, Onn, Pethboc, Ri Cymraeg A, B, C, Ch, D, Dd, E, F, Ff, G, Ng, H, I, L Breton A, B, K, D, E, F, G, H, C, C’h, I, J, L, M English A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N |

|

|

|

|

|

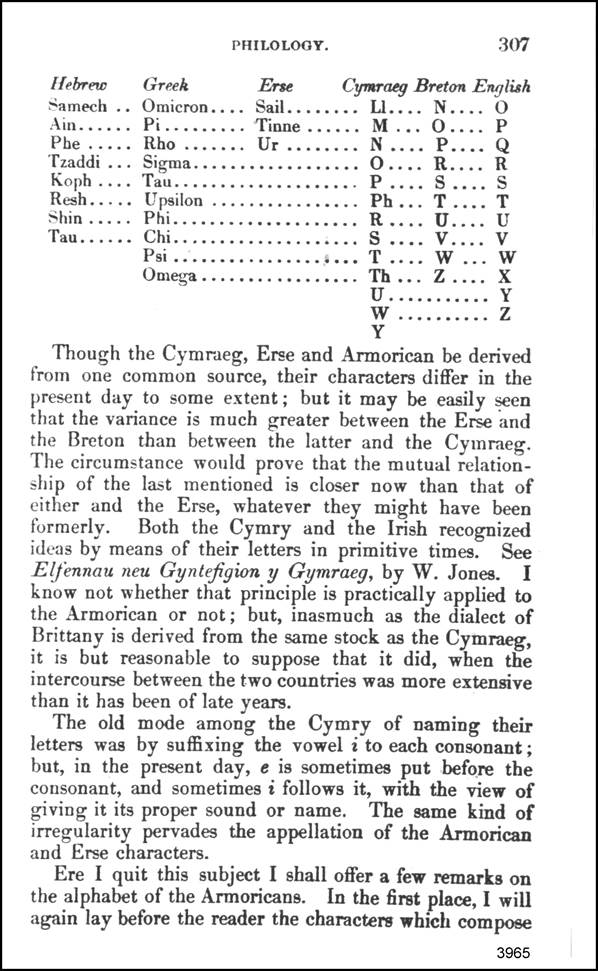

PHILOLOGY. 307. Hebrew Samech, Ain, Phe, Tzaddi, Koph, Resh, Shin, Tau Greek Omicron, Pi, Rho, Sigma, Tau, Upsilon, Phi, Chi, Psi, Omega Erse Sail, Tinne, Ur Cymraeg Ll, M, N, O, P, Ph, R, S, T, Th, U, W, Y Breton N, O, P, R, S, T, U, V, W, Y, Z English O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z Though the Cymraeg, Erse and Armorican be derived from one common

source, their characters differ in the present day to some extent; but it may

be easily seen that the variance is much greater between the Erse and the

Breton than between the latter and the Cymraeg. The circumstance would prove

that the mutual relationship of the last mentioned is closer now than that of

either and the Erse, whatever they might have been formerly. Both the Cymry

and the Irish recognized ideas by means of their letters in primitive times.

See Elfennau neu Gyntefigion y Gymraeg, by W. Jones. I know not whether that

principle is practically applied to the Armorican or not; but, inasmuch as

the dialect of Brittany is derived from the same stock as the Cymraeg, it is

but reasonable to suppose that it did, when the intercourse between the two

countries was more extensive than it has been of late years. The old mode among the Cymry of naming their letters was by suffxing

the vowel i to each consonant; but, in the present day, e is sometimes put

before the consonant, and sometimes i follows it, with the view of giving it

its proper sound or name. The same kind of irregularity pervades the

appellation of the Armorican and Erse characters. Ere I quit this subject I shall offer a few remarks on the alphabet of

the Armoricans. In the first place, I will again lay before the reader the

characters which compose |

|

|

|

|

|

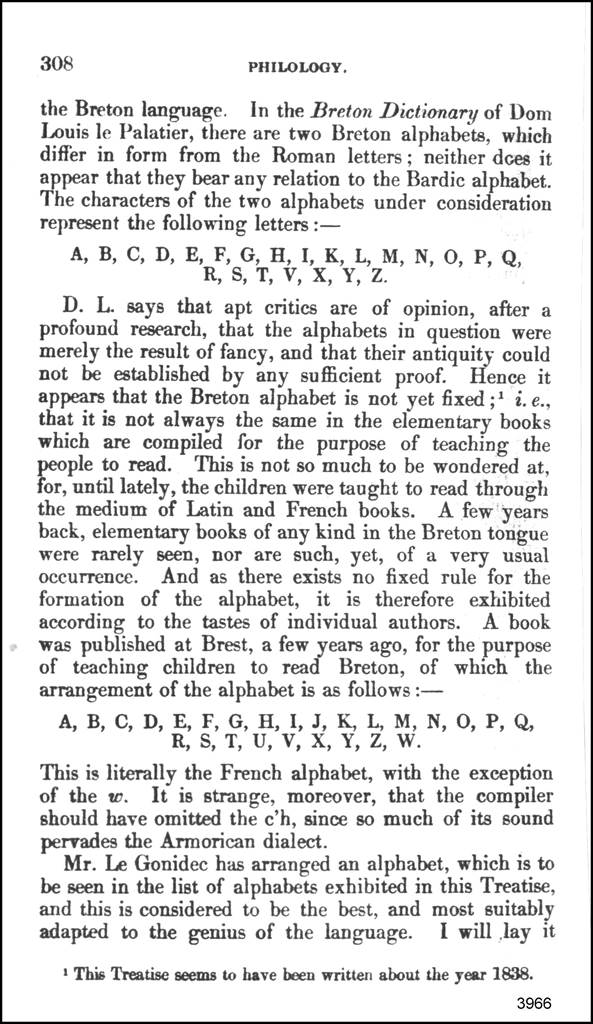

PHILOLOGY. 308. the Breton

language. In the Breton Dictionary of Dom Louis le Palatier, there are two

Breton alphabets, which differ in form from the Roman letters; neither does

it appear that they bear any relation to the Bardic alphabet. The characters

of the two alphabets under consideration represent the following letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, N O, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, X, Y, Z D. L. says that

apt critics are of opinion, after a profound research, that the alphabets in

question were merely the result of fancy, and that their antiquity could not

be established by any suffient proof. Hence it appears that the Breton

alphabet is not yet fixed (1) i.e., that it is not always the same in the

elementary books which are compiled for the purpose of teaching the people to

read. This is not so much to be wondered at, for, until lately, the children

were taught to read through the medium of Latin and French books. A few years

back, elementary books of any kind in the Breton tongue were rarely seen, nor

are such, yet, of a very usual occurrence. And as there exists no fixed rule

for the formation of the alphabet, it is therefore exhibited according to the

tastes of individual authors. A book was published at Brest, a few years ago,

for the purpose of teaching children to read Breton, of which the arrangement

of the alphabet is as follows:— A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, X, Y, Z, W. This is literally

the French alphabet, with the exception of the w. It is strange, moreover,

that the compiler should have omitted the c'h, since so much of its sound

pervades the Armorican dialect. Mr. Gonidec has

arranged an alphabet, which is to be seen in the list of alphabets exhibited

in this Treatise, and this is considered to be the best, and most suitably

adapted to the genius of the language. I will lay it (1) This Treatise

seems to have written about the year 1838. |

|

|

|

|

|

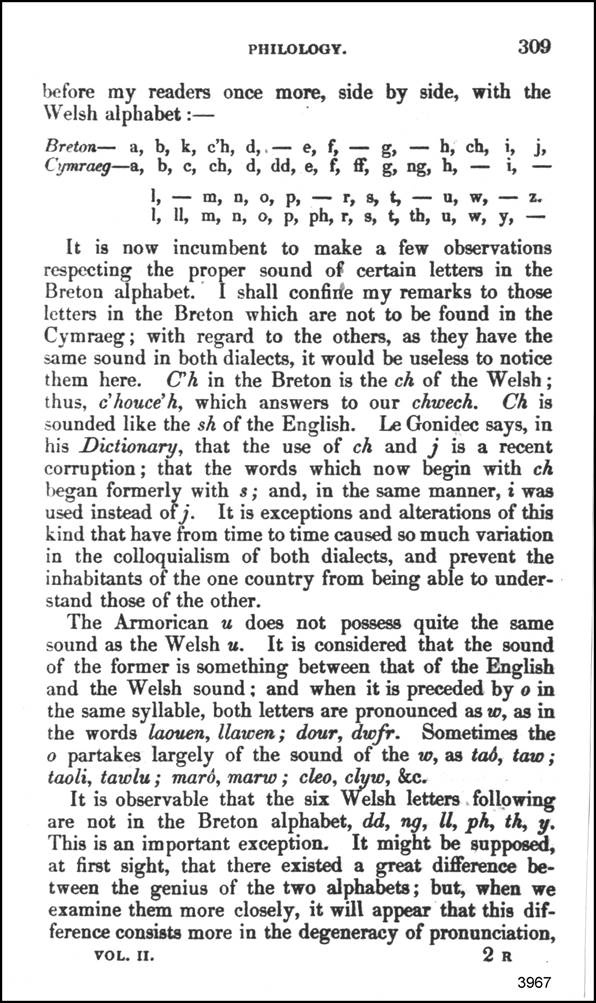

PHILOLOGY. 309. before my readers once more, side by side,

with the Welsh alphabet: Breton — a, b, k, c'h, d, -, e, f, -, g, -,

h, ch, i, j, l, -, m, n, o, p, -, r, s, t, -, u, w, -, z. Cymraeg—a, b, c, ch, d, dd, e, f, ff, g,

ng, h, -, i, -, l, ll, m, n, o, p, ph, r, s, t, th, u, w, y, -. It is now incumbent to make a few

observations respecting the proper sound of certain letters in the Breton

alphabet. I shall confine my remarks to those letters in the Breton which are

not to be found in the Cymraeg; with regard to the others, as they have the

same sound in both dialects, it would be useless to notice them here. C’h in

the Breton is the ch of the Welsh; thus, c'houce'h [sic; = c’houec’h], which

answers to our chwech. Ch is sounded like the sh of the English. Le Gonidec

says, in his Dictionary, that the use of ch and j is a recent corruption;

that the words which now begin with ch began formerly with s; and, in the

same manner, i was used instead of j. It is exceptions and alterations of

this kind that have from time to time caused so much variation in the

colloquialism of both dialects, and prevent the inhabitants of the one

country from being able to understand those of the other. The Armorican u does not possess quite the

same sound as the Welsh u. It is considered that the sound of the former is

something between that of the English and the Welsh sound; and when it is

preceded by o in the same syllable, both letters are pronounced as w, as in

the words laouen, llawen; dour, dwfr. Sometimes the o partakes largely of the

sound of the the w, as taô, tam; taoli, tawlu; marô, marw; cleo, clyw, &c

It is observable that the six Welsh letters

following are not in the Breton alphabet, dd, ng, ll, ph, th, y. This is an

important exception. It might be supposed, at first sight, that there existed

a great difference between the genius of the two alphabets; but, when we

examine them more closely, it will appear that this difference consists more

in the degeneracy of pronunciation, |

|

|

|

|

|

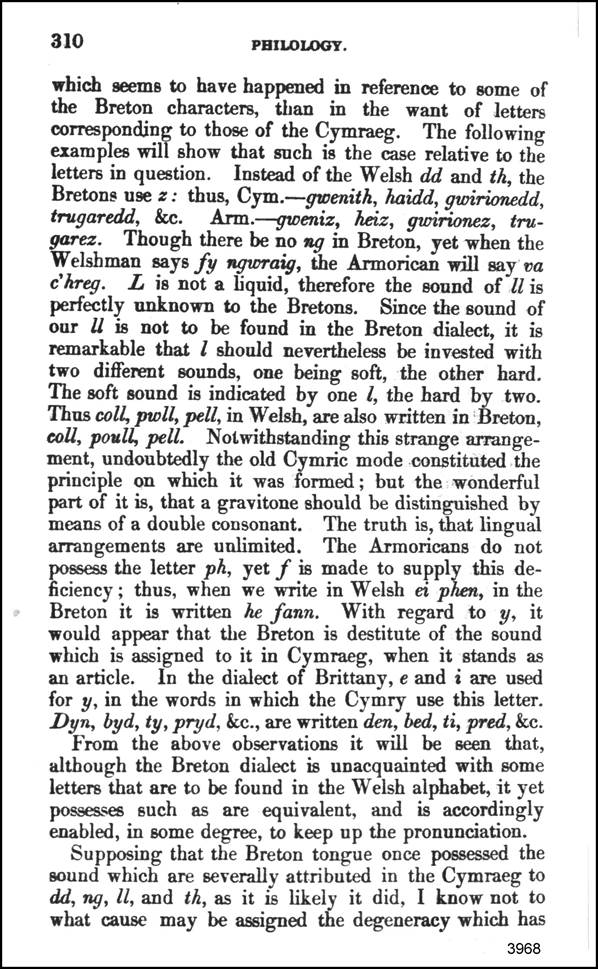

PHILOLOGY. 310. which seems to have happened in reference

to some of the Breton characters, than in the want of letters corresponding

to those of the Cymraeg. The following examples will show that such is the

case relative to the letters in question. Instead of the Welsh dd and th, the

Bretons use z: thus, Cym.— gwenith, haidd, gwirionedd, trugaredd, &c.

Arm.-— gweniz, heiz, gwirionez, trugarez. Though there be no ng in Breton,

yet when the Welshman says fy ngwraig, the Armorican will say va c'hreg. L is

not a liquid, therefore the sound of ll is perfectly unknown to the Bretons.

Since the sound of our ll is not to be found in the Breton dialect, it is

remarkable that I should nevertheless be invested with two different sounds,

one being soft, the other hard. The soft sound is indicated by one l, the

hard by two. Thus coll, pwll, pell, in Welsh, are also written in Breton,

coll, poull, pell. Notwithstanding this strange arrangement, undoubtedly the

old Cymric mode constituted the principle on which it was formed; but the

wonderful part of it is, that a gravitone should be distinguished by means of

a double consonant. The truth is, that lingual arrangements are unlimited.

The Armoricans do not possess the letter ph, yet f is made to supply this

deficiency; thus, when we write in Welsh ei phen, in the Breton it is written

he fann [sic; = fenn]. With regard to y, it would appear that the Breton is

destitute of the sound which is assigned to it in Cymraeg, when it stands as

an article. In the dialect of Brittany, e and i are used for y, in the words

in which the Cymry use this letter. Dyn, byd, ty, pryd, &c., are written

den, bed, ti, pred, &c. From the above observations it will be sæn

that, although the Breton dialect is unacquainted with some letters that are

to be found in the Welsh alphabet, it yet possesses such as are equivalent,

and is accordingly enabled, in some degree, to keep up the pronunciation. Supposing that the Breton tongue once

possessed the which are severally attributed in the Cymraeg to dd, ng, Il,

and th, as it is likely it did, I know not to what cause may be assigned the

degeneracy which has |

|

|

|

|

|

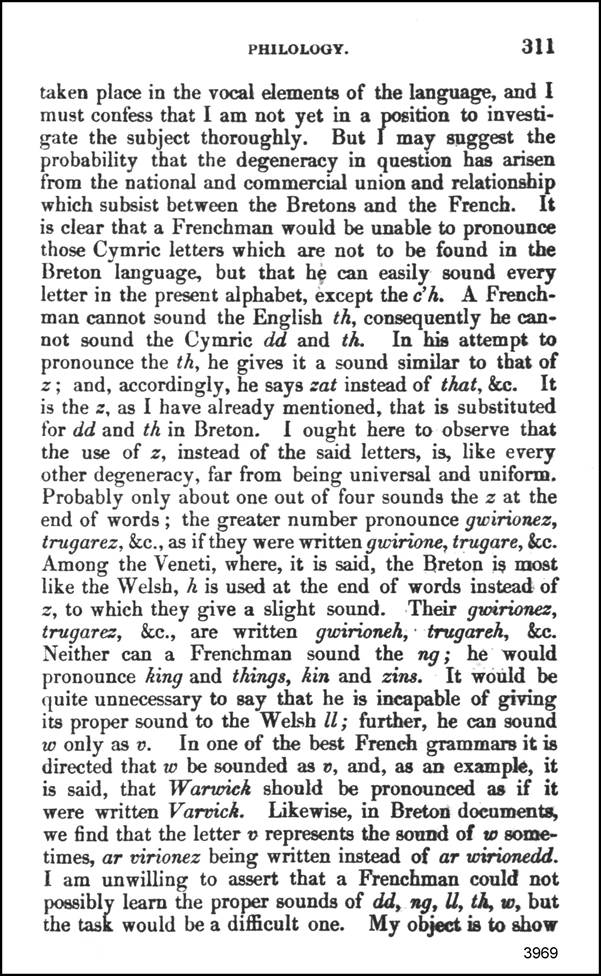

PHILOLOGY. 311 taken place in the vocal elements of the

language, and I must confess that I am not yet in a position to investigate

the subject thoroughly. But I may suggest the probability that the degeneracy

in question has arisen from the national and commercial union and

relationship which subsist between the Bretons and the French. It is clear

that a Frenchman would be unable to pronounce those Cymric letters which are

not to be found in the Breton language, but that he can easily sound every

letter in the present alphabet, except the c'h. A Frenchman cannot sound the

English th, consequently he cannot sound the Cymric dd and th. In his attempt

to pronounce the th, he gives it a sound similar to that of z; and,

accordingly, he says zat instead of that, &c. It is the z, as I have

already mentioned, that is substituted for dd and th in Breton. I ought here

to observe that the use of z, instead of the said letters, is, like every

other degeneracy, far from being universal and uniform. Probably only about

one out of four sounds the z at the end of words; the greater number

pronounce gwirionez, trugarez, &c., as if they were written gwirione,

trugare, &c. Among the Veneti, where, it is said, the Breton is most like

the Welsh, h is used at the end of words instead of z, to which they give a

slight sound. Their gwirionez, trugarez, &c., are written gwirioneh,

trugareh, &c. Neither can a Frenchman sound the ng; he would pronounce

king and things, kin and zins. It would be quite unnecessary to say that he

is incapable of giving its proper sound to the Welsh ll; further, he can

sound w only as v. In one of the best French grammars it is directed that w

be sounded as v, and, as an example, it is said, that Warwick should be

pronounced as if it were written Varvich. Likewise, in Breton documents, we

find that the letter v represents the sound of w sometimes, ar virionez being

written instead of ar wirionedd. I am unwilling to assert that a Frenchman

could not possibly learn the proper sounds of dd, ng, u, th, v, but the task

would be a diffcult one. My object to |

|

|

|

|

|

PHILOLOGY. 312. what a ruinous destiny would await them,

were they to to pass through the lips of the generality of the French, and

thc nature of the vocal degeneracy which follows a close and long connexion

between the French and a people in possession of a Iangunge that has in it

such letters. I wish to show the probability that what I have noticed has

contributed to corrupt the original sounds of the Breton tongue. The alleged

cause answers exactly to the degenerate effect which must have occurred in the

sounds of the Breton, for it is clear that this and the Cymraeg were

originally but one language, and that we have no reason to suppose that it is

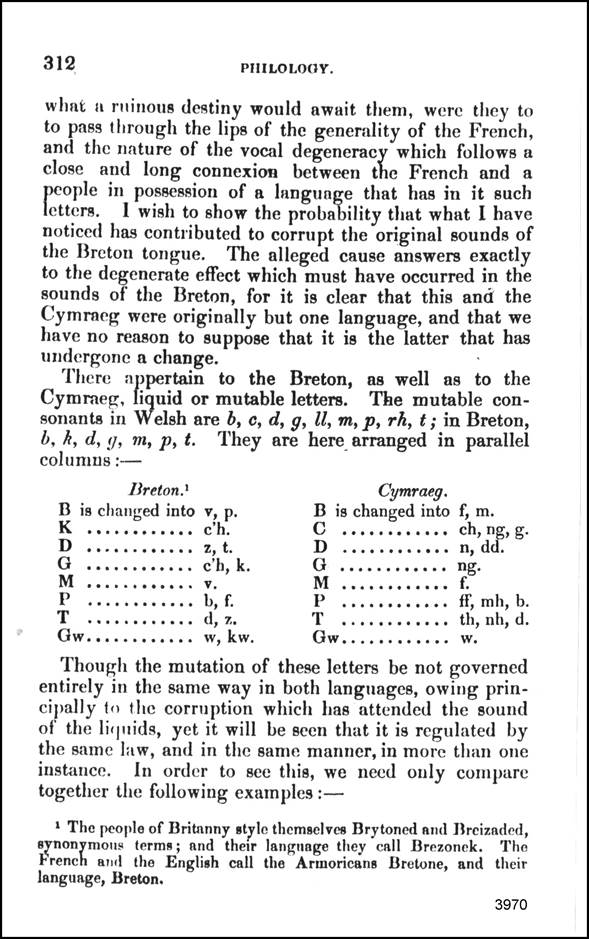

the latter that has undergone a change. There appertain to the Breton, as well as

to the Cymraeg, liquid or mutable letters. The mutable consonants m Welsh are

b, c, d, g, Il, m, p, rh, t; in Breton, b, h, d, g, m, p, t. They are here.

arranged in parallel columns: - Breton. (1) B is changed into v, p. K - c'h, k. D – z,

t. G – c’h, k. M – v. P – b, f. T – d, z. Gw – w, kw. Cymraeg. B is changed into f, m. C – ch, ng, g. D –

n, dd. G – ng. M – f: P – ff, mh, b. T – th, nh, d. Gw - w. Though the mutation of these letters be not

governed entirely in the same way in both languages, owing principally to the

corruption which has attended the sound of the liquids, yet it will be seen

that it is regulated by the same law, and in the same manner, in more than

one instance. In order to see this, we need only compare together the

following examples: - (1) The people of Britnnny style themselves

Brytoned and Breizaded, synonymous terms; and their language they call

Brezonek. The French and the English call the Armoricans Bretone, [sic; = Bretons]

and their language, Breton. |

|

|

|

|

|

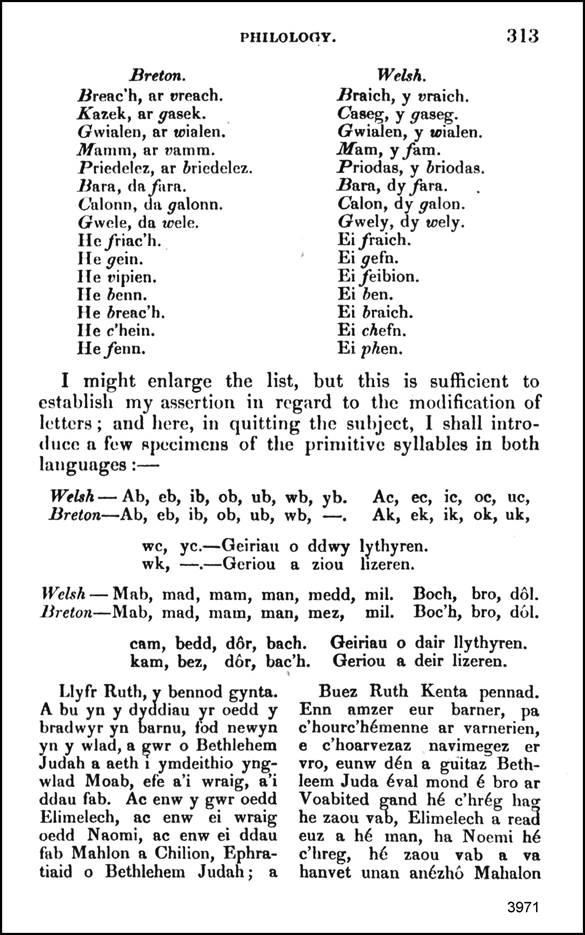

PHILOLOGY. 313. |

...

|

|

|

|

|

314 PHILOLOGY. hwy a ddaethant i wlad Moab, ac a fuant yno. hag égilé chelion ginidig e oant euz a Ephrata é Bethleem Juda ead é bró ar Voabited é c'houmzond enô. I am indebted to Mr. J. Jenkins, of Morlaix (lately of Maes y Cwmwr), for a great many of the preceding sentiments, which are scattered throughout his letters in the Gral, and in his An A, B, K. I also received assistance from writers in Seren Gomer. Ere I close these observations, I will confidently say there is not so much resemblance between any other two languages under the sun as there is between the two in question; and that the difference which exists at the present day has been occasioned by the distance of one country from the other. We must consider, moreover, that a cessation of national intercourse between them has continued during several centuries. Also, if the French people, situated beyond the sea, have tended to estrange the pronunciation and speech of the two nations, perhaps that the English, on this side, have had a similar effect. 'l'hese, with other causes, have brought about such a change in the original language, that it is quite hopeless to see it again as one with itself, and intelligible to the two races - the Bretons and the Cymry. (To be continued.) |

.....

(delwedd J6261)

.....

|

|

|

|

|

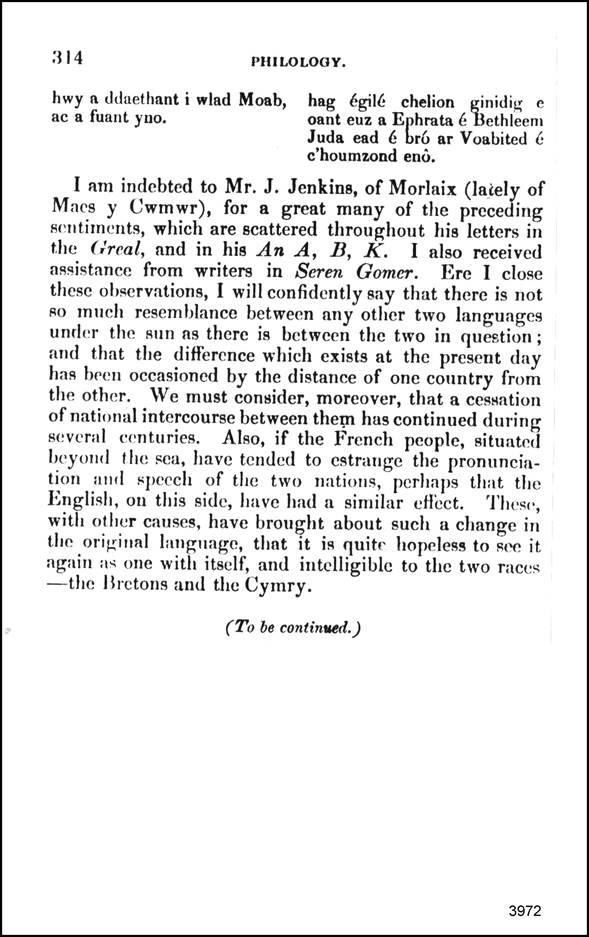

The Cambrian Journal, Volume 3, 1856,

pp36-40 A TREATISE ON THE CHIEF PECULIARITIES THAT DISTINGUISH THE CYMRAEG,

AS SPOKEN BY THE INHABITANTS OF GWENT AND MORGANWG RESPECTIVELY. By PERERINDODWR (Continued from

page 314, vil. ii) THE

GWENHWYSEG, OR DIALECT OF GWENT I will now endeavour to ascertain what is

meant by “The Gwenhwyseg” or “Dialect of Gwent.” It may be supposed

sometimes, when so much is said about the Gwenhwyseg, that it is a language

distinct from the Cymraeg. Iolo Morgannwg, at page 20 of his Poems Lyric

and Pastoral, thus observes of the dialect of Gwent, or Siluria:- |

|

|

|

|

|

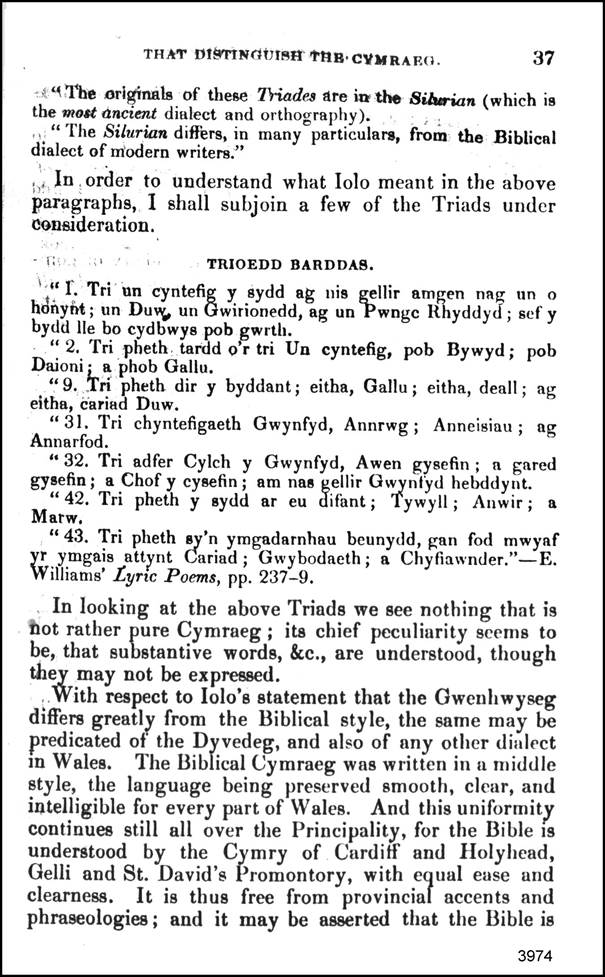

37. “The originals of these Triades are

in the Silurian (which is the most ancient dialect and orthography.) The Silurian differs, in many

particulars, from the Biblical dialect of modern writers.” In order to understand what Iolo meant in

the above paragraphs, I shall subjoin

a few of the Triads under

consideration. TRIOEDD BARDDAS. “1.

Tri un cyntefig y sydd ag nis gellir amgen nag un o hdnynt; un Duw, un Gwirionedd, ag un

Rhyddyd; sef y bydd lle bo cydbwys

pob gwrth. “2.

Tri pheth tardd o r tri Un cyntefig, pob Bywyd; pob Daioni; a phob Gallu. “9.

Tri pheth dir y byddant; eitha, Gallu; eitha, deall; ag eitha, cariad Duw. “31.

Tri chyntefigaeth Gwynfyd, Annrwg; Anneisiau; ng Annarfod.

“32.

Tri adfer Cylch y Gwynfyd, Awen gysefin; a gared gysefin; a Chof y cysefin; am nas gellir

Gwynfyd hebddynt. “42.

Tri pheth y sydd ar eu difant; Tywyll; Anwir; a Marw.

“43.

Tri pheth sy'n ymgadarnhau beunydd, gan fod mwyaf yr ymgais attynt Cariad; Gwybodaeth; a

Chyfiawnder."—E. Williams' Lyric

Poems, pp. 237—9. In looking at the above Triads we see

nothing that is not rather pure

Cymraeg; its chief peculiarity seems to

be, that substantive words, &c., are understood, though they may not be expressed. With respect to Iolo’s statement that the

Gwenhwyseg differs greatly from the Biblical style, the same may be

predicated of the Dyvedeg (the dialect of

Dyfed = south-west Wales), and

also of any other dialect in Wales. The Biblical Cymraeg was written in a

middle style, the language being preserved smooth, clear, and intelligible

for every part of Wales. And this uniformity continues still all over the

Principality, for the Bible is understood by the Cymry of Cardiff and

Holyhead, Gelli (= Y

Gelligandryll, ‘Hay on Wye’) and St. David’s Promontory, with equal

ease and clearness. It is thus free from provincial accents and

phraseologies; and it may be asserted that the Bible is |

|

|

|

|

|

38. not written in the dialect of Dyved, or of Powys,

with as much truth as that it is not written in the Gwenhwyseg. (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

39. adversity. How many orthographical changes

soever may be seen in old Welsh manuscripts, and however varied are the

present modes of spelling the ancient language, yet it cannot be believed for

a moment that the language of Gwent, like those of Cornwall and Armorica,

possesses a vocabulary peculiar to itself; for, in respect of grammatical

construction, the language of Gwent was the same as that of Powys, or of any

other part of Wales; its distinctiveness consisted in its provincial

conditions and cultivated elegance. |

|

|

|

|

|

40. added much to the knowledge of their tribe from

the learning of the Romans, in which the bards seemed especially to have

improved. It was, undoubtedly, from that source that a knowledge of the

poetical quantities was derived, - a knowledge which has never to this day

been possessed by the bards of any other province of Wales. About the said

era, the art of poetry was greatly cultivated,- the principal canons adopted

to the tendencies of the language were traced, - and resplendent learning was

scattered over the country by the ecclesiastics of the blessed College of

Cattwg the Wise, at Llanveithin (Llancarvan)

(Llanfeuthin, (Llancarfan)), (Llancarfan),

and Bangor Illtyd (Bangor

Illtud), in Llanilltyd Vawr (Llanilltud Fawr), as well as of other

celebrated schools. |

|

|

The Cambrian Journal, Volume 3, 1856.

Section 2 pp239-253 239. commendation bestowed upon the several

parts, and have much pleasure in introducing the work to our readers as a

most valuable contribution to the literature of the Principality. The work

has been published by subscription, and the subscribers may be warmly

congratulated on the possession of a volume which reflects the highest credit

upon its authors, and which ought to be found in the library of every

gentleman connected with Wales, or interested in Cambrian literature. THOMAS STEPHENS. Merthyr Tydvil, May, 1856. A TREATISE ON THE CHIEF PECULIARITIES THAT DISTINGUISH THE CYMRAEG,

AS SPOKEN BY THE INHABITANTS OF GWENT AND MORGANWG RESPECTIVELY. By PERERINDODWR (Continued from

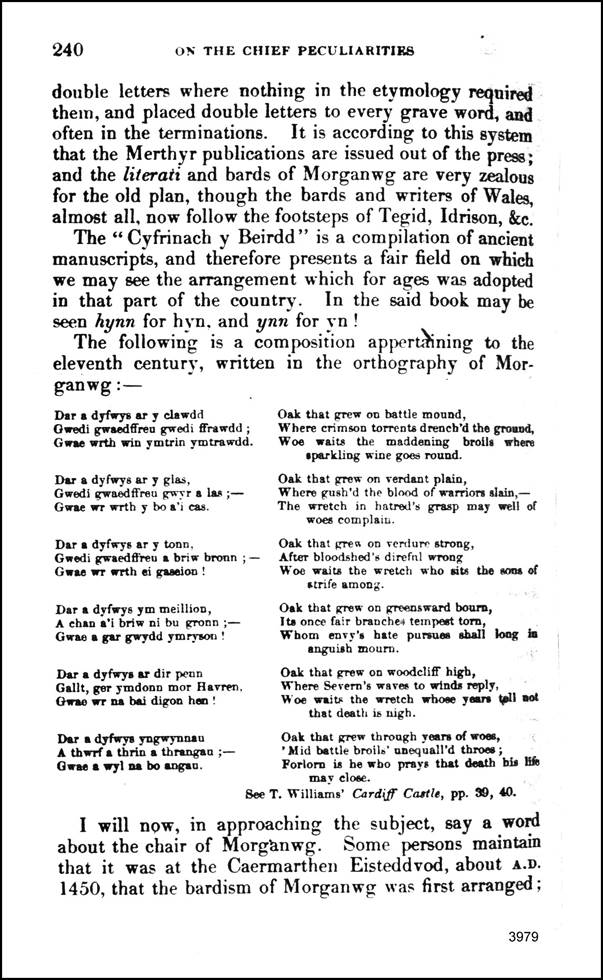

page 40) THE DIALECT OF MORGANWG MORGANWG boasts of the antiquity of its

literary institutions, its bardic chair, and the provincial peculiarities of

its dialect; and it is my opinion that there is neither in practice, nor on

record, anything so old as some things which are used in the dialect of this

province. There was a hot controversy, lately, between the Rev. John Jones,

(Tegid,) of Oxford, and the Rev. W. B. Knight, of Margam, respecting the

orthography of the Welsh. The former insisted, vehemently, upon the etymology

of the language as the criterion of orthography, and made use of marks for

the purpose of distinguishing the grave and light sounds. His system is to be

seen in the Essay for which he received the gold medal at the Caermarthen

Eisteddvod, A.D. 1829. The latter followed the orthography of the old Welsh

Bibles, using a multiplicity of |

|

|

|

|

|

ON THE CHIEF PECULIARITIES. 240. |

|

|

|

|

|

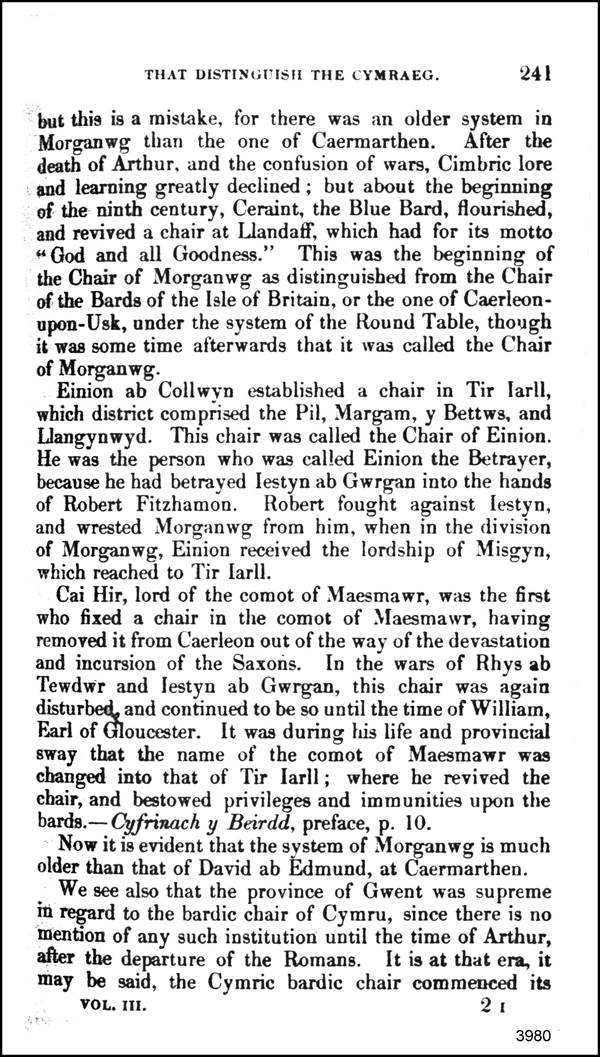

THAT DISTINGUISH THE CYMRAEG. 241 but this is a mistake, for there was an

older system in Morganwg than the one of Caermarthen. After the death of

Arthur, and the confusion of wars, Cimbric lore and learning greatly

declined; but about the beginning of the ninth century, Ceraint, the Blue Bard,

flourished, and revived a chair at Llandaff, which had for its motto

"God and all Goodness." This was the beginning of the Chair of

Morganwg as distinguished from the Chair of the Bards of the Isle of Britain,

or the one of Caerleon-upon-Usk, under the system of the Round Table, though

it was some time afterwards that it was called the Chair of Morganwg. Einion ab Collwyn established a chair in

Tir Iarll, which district comprised the Pil, Margam, y Bettws, and

Llangynwyd. This chair was called the Chair of Einion. He was the person who

was called Einion the Betrayer, because he had betrayed Iestyn ab Gwrgan into

the hands of Robert Fitzhamon. Robert fought against Iestyn, and wrested

Morganwg from him, when in the division of Morganwg, Einion received the

lordship of Misgyn, which reached to Tir Iarll. Cai Hir, lord of the comot of Maesmawr, was

the first who fixed a chair in the comot of Maesmawr, having removed it from

Caerleon out of the way of the devastation and incursion of the Saxons. In

the wars of Rhys ab Tewdwr and Iestyn ab Gwrgan, this chair was again

disturbed, and continued to be so until the time of William, Earl of

Gloucester. It was during his life and provincial sway that the name of the

comot of Maesmawr was changed into that of Tir Iarll; where he revived the

chair, and bestowed privileges and immunities upon the bards. - Cyfrinach y

Beirdd, preface, p. 10. Now it is evident that the system of

Morganwg is much older than that of David ab Edmund, at Caermarthen. We see also that the province of Gwent was

supreme in regard to the bardic chair of Cymru, since there is no mention of

any such institution until the time of Arthur, after the departure of the

Romans. It is at that era, it may be said, the Cymric bardic chair commenced

its |

|

|

|

|

|

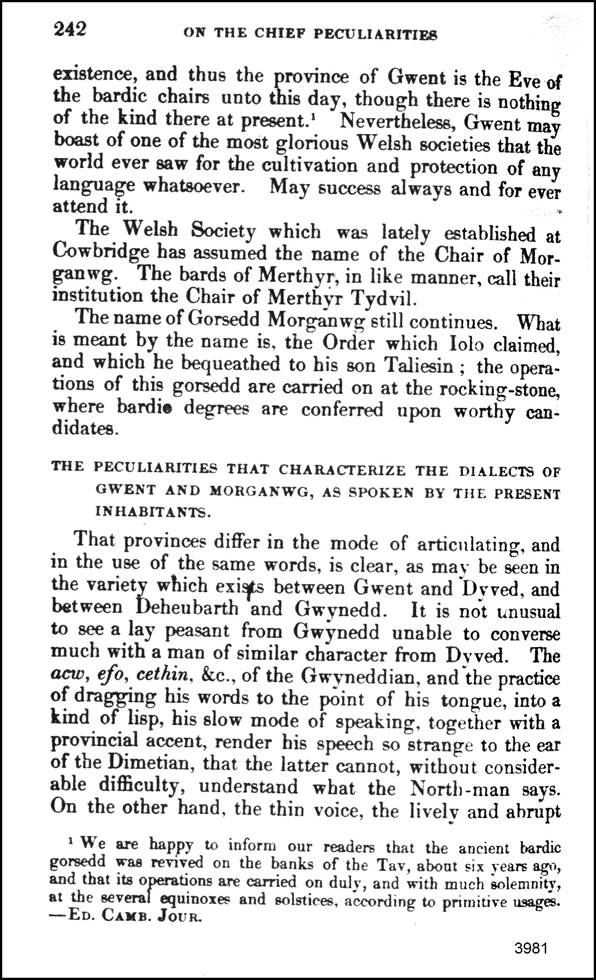

242. existence, and thus the province of Gwent

is the Eve of the bardic chairs unto this day, though there is nothing of the

kind there at present. (1) Nevertheless, Gwent may boast of one of the most

glorious Welsh societies that the world ever for the cultivation and

protection of any language whatsoever. May success always and for ever attend

it. The Welsh Society which was lately

established at Cowbridge has assumed the name of the Chair of Morganwg. The

bards of Merthyr, in like manner, call their institution the Chair of Merthyr

Tydvil. The name of Gorsedd Morganwc still What is

meant by the name is, the Order which Iolo claimed, and which he bequeathed

to his son Taliesin; the operations of this gorsedd are carried on at the

rocking-stone; where bardic degrees are conferred upon worthy candidates. THE

PECULIARITIES THAT CHARACTERIZE THE DIALECTS OF GWENT AND MORGANWG, AS SPOKEN

BY THE PRESENT INHABITANTS. That provinces differ in the mode of

articulating, and in the use of the same words, is clear, as may be seen in

the variety which exists between Gwent and Dyved, and between Deheubarth and

Gwynedd. It is not unusual to see a lay peasant from Gwynedd unable to

converse with a man of similar character from Dyved. The acw, efo, cethin

&c. , of the Gwyneddian, and the practice of dragging his words to the

point of his tongue, into a kind o lisp, his slow mode of speaking, together

with a provincial accent, render his speech so strange to the ear of a

Dimetian, that the latter cannot, without considerable difficulty, understand

what the North-man says. On the other hand, the thin voice, the lively and

abrupt (1) We are happy to inform our readers that

tbe ancient bardic gorsedd was revived on the banks of the Tav, about six

yeaß ago, and that its operations are carried on duly, and with much

solemnity, at the several equinoxes and solstices, according to primitive

usagæ. —ED. CAMB. JOUR. |

|

|

|

|

|

243. utterance of the Dimetian, together with

his lweth, ymbeidis, siompol, &c., and his peculiar accent, cause

his language to be rather unintelligible to the inhabitants of Gwynedd. |

|

|

|

|

|

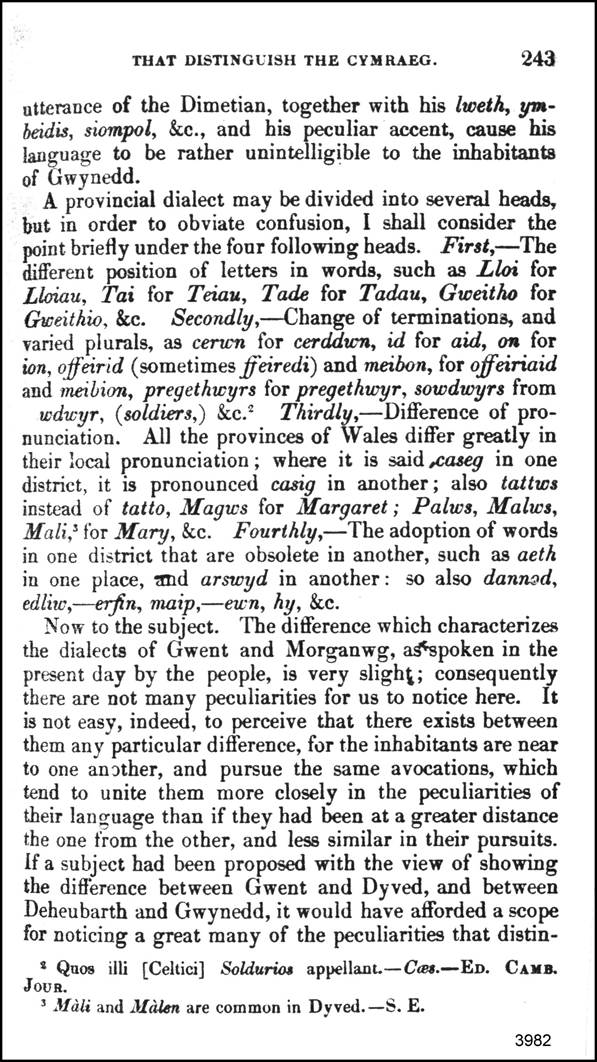

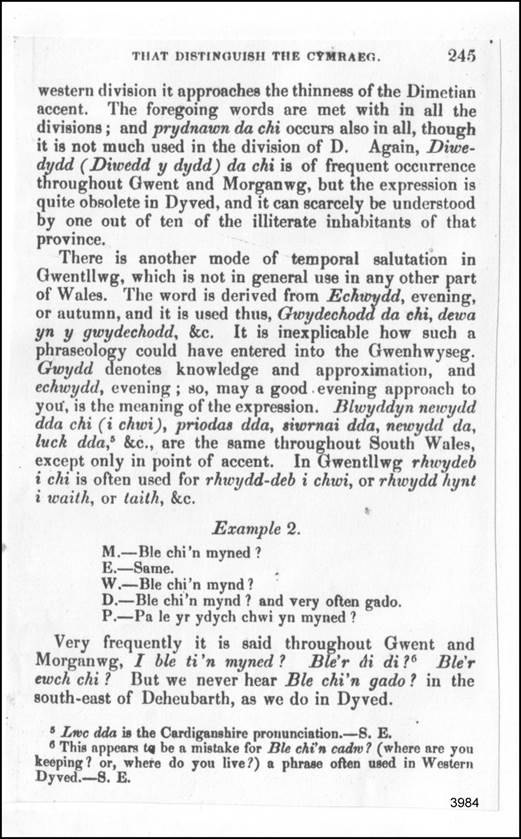

244. the dialects of those countries

respectively. But though the field on the present occasion is so limited, I

will endeavour to creep towards some plan, whereby I may show what I can of

the characterisitcs of the dialects of Gwent and Morgannwg. Example l. M. — Dydd da chi. E. — Same. W. D. — Dydd da chi, and dydd dawch. P.(4) --- Dydd da i chwi; the verb Bydded

being understood. The pronunciation of the central division

is the same as that of the eastern, in the above salutation, but in the (4) M. denotes the Middle division, E. the

Eastern, W. the Western, D. Dyved, and P. the Cymraeg in its purity. Let this

be borne in mind throughout all the examples in the following pages. |

.....

Example 1

|

|

|

(a good day to

you) |

|

|

(East

= the area east of the Rhymni river) |

Dydd

da chi |

|

|

(Middle, = the area

between the Rhymni river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

Dydd da chi |

|

|

(West = the area west of

Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Cwm |

Dydd da chi, and dydd dawch |

|

|

(Dyfed = south-west

Wales) |

Dydd da chi, and dydd dawch |

|

|

(= “Cymraeg in its

purity”, that is, Standard Welsh) |

Dydd da i chwi; the

verb Bydded being understood |

|

|

|

|

|

(1) (A footnote adds: “Lwc dda is the Cardiganshire

pronunciation. - S.E” - this probably means that “luck”

represents the modern English pronunciation, which would be spelt “lyc” in

Welsh), &c., are the

same throughout Example 2. M.—Ble chi 'n

myned ? E.—Same. W.—Ble chi'n mynd

? D.—Ble chi 'n mynd

? and very often gado. P.—Pa le yr ydych

chwi yn myned ?

(A footnote adds: “This appears to

be a mistake for Ble chi’n cadw? (where are you keeping? or, where do you

live?) a phrase often used in Ble’r ewch chi? |

..

Example 2

|

|

|

(where are you going?) |

|

|

(East = the area east of

the Rhymni river) |

Ble chi’n mynd? |

|

|

(Middle, = the area

between the Rhymni river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

Ble chi’n mynd?

|

|

|

(West = the area west of

Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Cwm |

Ble chi’n mynd? |

|

|

(Dyfed = south-west

Wales) (Is this from English ‘to gad’ = go about?) |

Ble chi’n mynd? and

very often gado. |

|

|

(= “Cymraeg in its

purity”, that is, Standard Welsh) |

Pa le yr ydych chwi yn

myned? |

.....

(delwedd

3985) (tudalen 246)

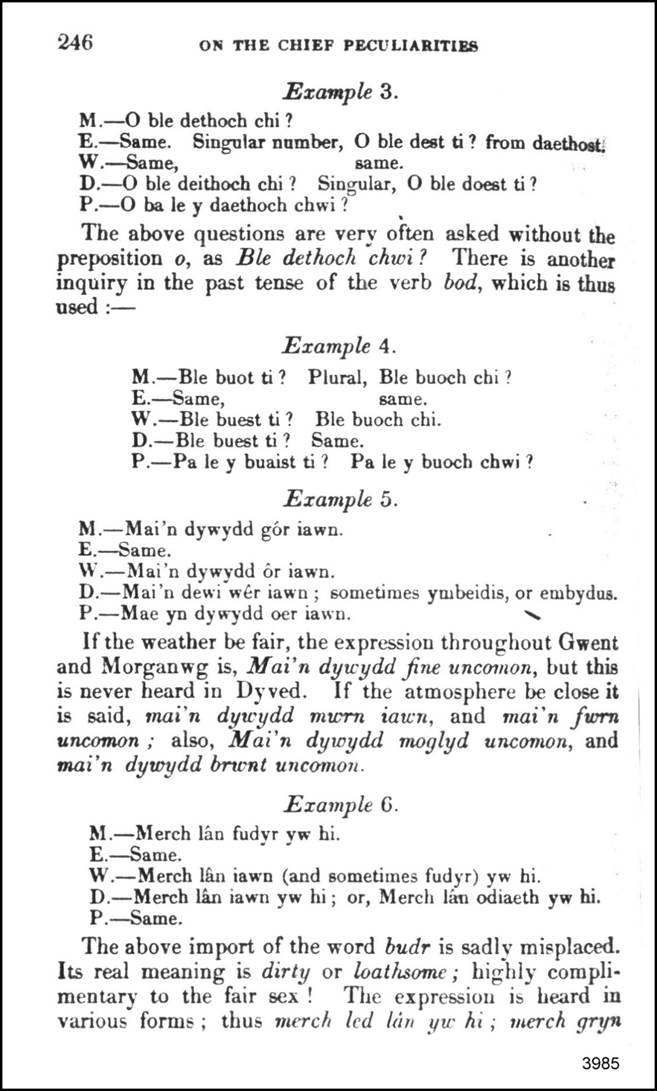

Example 3

|

|

|

(where have you come

from / where did you come from?) |

|

|

(East = the area east of

the Rhymni river) |

O ble dethoch chi? |

|

|

(Middle, = the area

between the Rhymni river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

O ble dethoch chi? Singular

number, |

|

|

(West = the area west of

Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Cwm |

O ble dethoch chi? Singular

number, |

|

|

(Dyfed = south-west

Wales) |

O ble deithoch chi? Singular, |

|

|

(= “Cymraeg in its

purity”, that is, Standard Welsh) |

O ba le y daethoch chi? |

The above questions are very often asked without the preposition o, as Ble

dethoch chwi?

There is another inquiry in the past tense of

the verb bod, which is thus used:-

Example 4

|

|

|

(where have you been /

where were you?) |

|

|

(East = the area east of

the Rhymni river) |

Ble

buot ti? Plural, Ble buoch chi? |

|

|

(Middle, = the area

between the Rhymni river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

Ble

buot ti? Plural, Ble buoch chi? |

|

|

(West = the area west of

Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Cwm |

Ble

buest ti? Plural, Ble buoch chi? |

|

|

(Dyfed = south-west

Wales) |

Ble

buest ti? Plural, Ble buoch chi? |

|

|

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”,

that is, Standard Welsh) |

Pa

le y buaist ti? Plural, Pa le y buoch chwi? |

Example 5

|

|

|

(It’s very cold

weather) |

|

|

(East = the area east of

the Rhymni river) |

Mai’n dywydd gôr iawn |

|

|

(Middle, = the area

between the Rhymni river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

Mai’n dywydd gôr iawn

|

|

|

(West = the area west of

Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Cwm |

Mai’n dywydd ôr iawn |

|

|

(Dyfed = south-west

Wales) |

Mai’n dewi wêr iawn; sometimes ymbeidis, or embydus |

|

|

(= “Cymraeg in its

purity”, that is, Standard Welsh) |

Mae yn dywydd oer iawn

|

If the weather be fair, the expression throughout Gwent and Morganwg is,

Mai’n dywydd fine uncomon, but this is never heard in Dyved. If the atmosphere be close it is

said,

mai’n dywydd mwrn iawn, and mai’n fwrn uncomon;

also, Mai’n dywydd moglyd uncomon, and

mai’n dywydd brwnt uncomon.

Example 6

|

|

|

(She’s a very beautiful

girl) |

|

|

(East = the area east of

the Rhymni river) |

Merch

lân fudyr yw hi |

|

|

(Middle, = the area

between the Rhymni river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

Merch

lân fudyr yw hi |

|

|

(West = the area west of

Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Cwm |

Merch

lân iawn yw hi |

|

|

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

Merch

lân iawn yw hi; or Merch lân odiaeth yw hi |

|

|

(= “Cymraeg in its

purity”, that is, Standard Welsh) |

Merch

lân iawn yw hi; or Merch lân odiaeth yw hi |

The above import of the word budr is sadly misplaced. Its real meaning

is dirty or loathsome;

highly complimentary to the fair

sex! The expression is heard in various forms; thus merch led lân yw hi;

merch gryn

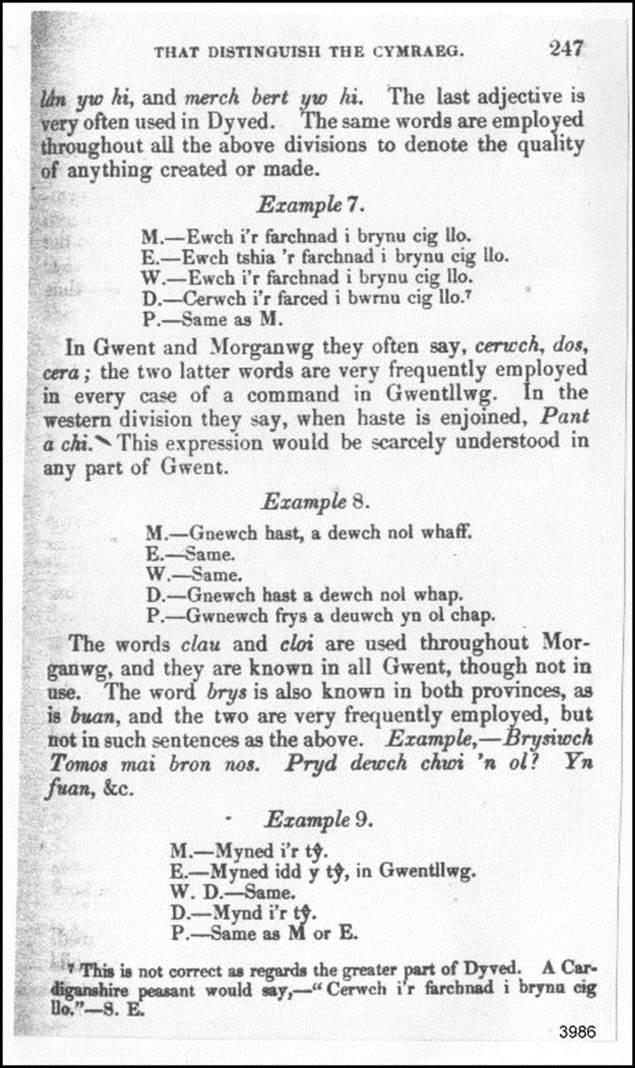

(delwedd 3986) (tudalen 247)

lân yw

hi, and merch

bert yw hi.The last adjective is very often used in Dyved. The same words

are employed throughout all the above divisions to denote the quality of

anything created or made.

(In standard

Welsh glân = pure, clean; in the south it is also ‘beautiful, pretty, fair’. In

the north and in standard Welsh ‘budr’ = dirty. In the south the word for dirty

is ‘brwnt’, and ‘budr’ is used as an intensifier, rather as in English

terribly, awfully, dead, etc. - awfully pretty, dead pretty. In the spoken

Welsh in both north and south, budr > budur)

Example

7

|

|

|

(Go to the market to buy veal) |

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni river) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

In Gwent and

Morganwg they often say, cerwch, dos, cera; the two latter words

are very frequently employed in every case of a command in Gwentllwg. In the

western division they say, when haste is enjoined, Pant a chi (in fact, Bant â chi). This expression would be scarcely

understood in any part of Gwent.

Example

8

|

|

|

(Hurry up, and come back at once) |

|

|

(1) E. Gwnech hast, a dewch nol

whaff

|

(East = the area east of the Rhymni river) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) (chap = ??) |

The words clau and cloi are used throughout Morganwg, and they are known in all

Gwent, though not in use. The word brys is also known in both provinces, as is

buan, and the two are very frequently enployed, but not in such sentences as

the above. Example, - Brysiwch Tomos mai bron nos. Pryd dewch chwi’n

ol? Yn fuan, &c, (dewch

chwi would be rather dewch chi)

Example

9

|

|

|

(go to the house) |

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni river) (This would in fact

be “mynad”) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) (This would in fact be” mynad”) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

..................

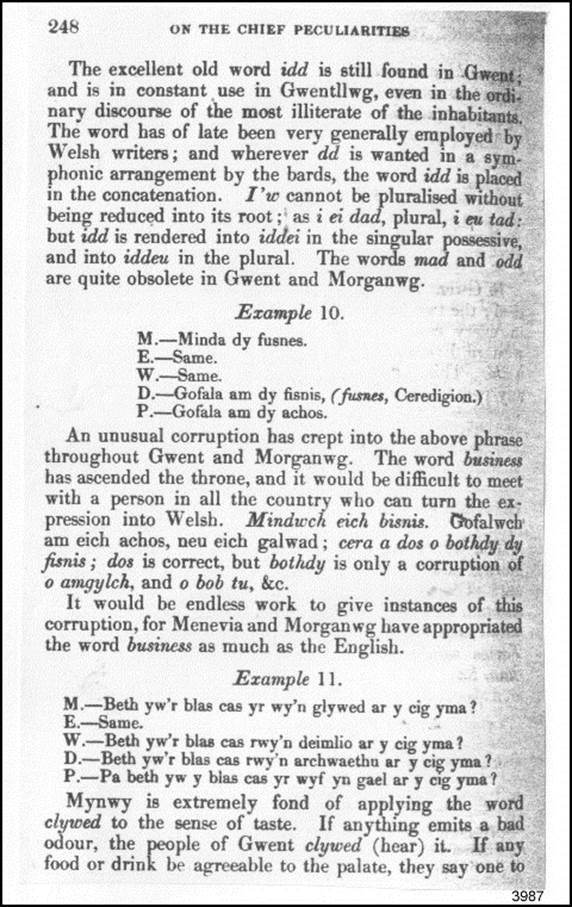

(delwedd 3987) (tudalen 248)

The excellent old

word idd is still found in Gwent;

and is in constant use in Gwentllwg, even in the discourse of the most

illiterate of the inhabitants. The words has of late been very generally

employed by Welsh writers; and wherever dd is wanted in a

symphonic arrangement by the bards, the word idd is placed in

the concatenation. I’w cannot be pluralised without being

reduced into its root; as i ei dad, plural i eu tad;

but idd is rendered into iddei in the

singular possessive, and into iddeu in the plural. (In fact, to his / to her / to its -

iddi - is the same as to their - iddi) The words mad (??) and odd (=

from) are

quite obsolete in Gwent and Morganwg.

Example

10

|

|

|

(mind your business) |

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni river) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

An unusual corruption has crept into the above phrase throught Gwent and

Morganwg. The word business has ascended the throne, and it

would be difficult to meet with a person in all the country who can turn the

expression into Welsh. Mindwch eich bisnis. Gofalwch am eich achos,

neu eich galwad; cera a dos o bothdy dy fisnis; dos is

correct, but bothdy is only a corruption of o amgylch,

and o bob tu, &c.

It would be endless work to give instances of this corruption, for Menevia and

Morganwg have appropriated the word business as much as the

English.

Example

11

|

|

|

(What’s the bad taste that can I taste on

ths meat?) |

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni

river) (in fact, clywad would be the pronunciation) (literal

translation: what is the bad taste I am perceiving (also ‘hearing’) on the

meat here?) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) (in fact, clywad would be the

pronunciation) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

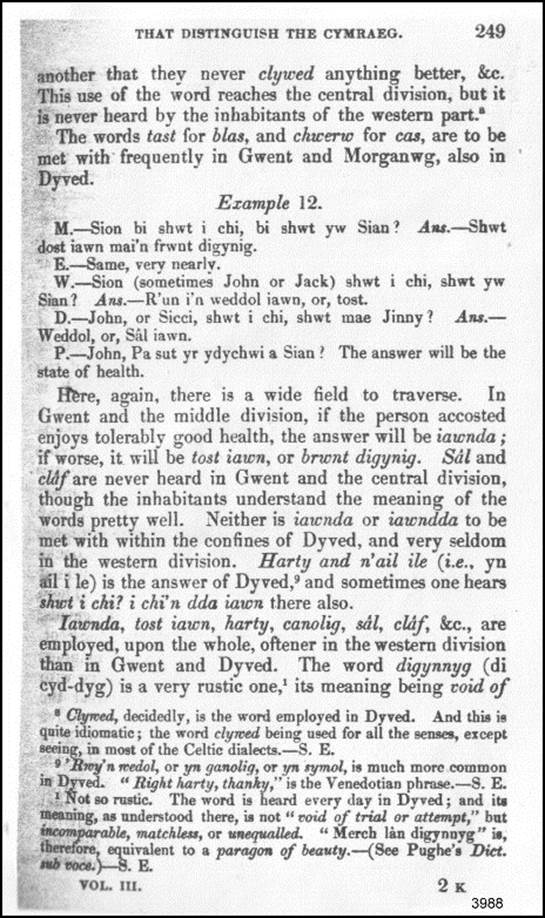

Mynwy is extremely

fond of applying the word clywed to the sense of taste. If anything

omits a bad odour, the people of Gwent clywed (hear) it. If

any food or drink be agreeable to the palate, they say one to

(delwedd 3988) (tudalen 249)

another

they never clywed anything better, &c. This use of the

word reaches the central divison, but is never heard by the inhabitants of the

western part.

(A footnote

adds: “Clywed, decidely, is the word employed in Dyved. And this is quite

idiomatic; the word clywed being used for all the senses, except seeing, in

most of the Celtic dialects. - S.E.)

Example

12

|

|

|

(Siôn, how are you, how is Siân?) |

|

|

(1) E. Same very nearly |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni

river) (i.e. very nearly the same as the next example; in the original

text, the ‘east’ sentences come after the ‘middle’ sentences) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) (I’m fine (‘fairly all right’), or

bad) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) (I’m fine, or

very sick) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

Here, again, there is a wide field to travers. In Gwent and the middle

division, if the person accosted enjoys tolerably good health, the answer will

be iawnda; if worse, it will be tost iawn, or brwnt

digynig.

Sâl and clâf are never heard in

Gwent and the central division, though the inhabitants understand the meaning

of the words pretty well. Neither is iawnda or iawndda to

be met with within the confines of Dyved, and very seldom in the western

division. Harty and n’ail ile (i.e. yn ail i le) is the

answer in Dyved and sometimes one hears shwt i chi? i chi’n dda

iawn (how are you? are you very well?) there also.

(A footnote adds: ‘Rwy’n weddol, or yn ganolig, or yn symol, is much more

common in Dyved. “Right harty, thanky” is the Venedotian phrase.-S.E.)

Iawnda,

tost iawn,

harty,

canolig,

sâl,

clâf, &c.

are employed, upon the whole, oftener in the western division than in Gwent and

Dyved. The word digynnyg (di-cyd-dyg) is a very rustic one

(A footnote adds: Digynnig - Not so rustic. The word is

heard every day in Dyved; and its meaning, as understood there, is not “void of

trial or attempt,” but incomparable, matchless or unequalled. “Merch lân

digynnyg” is, therefore, equivalent to a paragon of beauty. - (See Pughe’s

Dict. sub voce.) - S.E. )

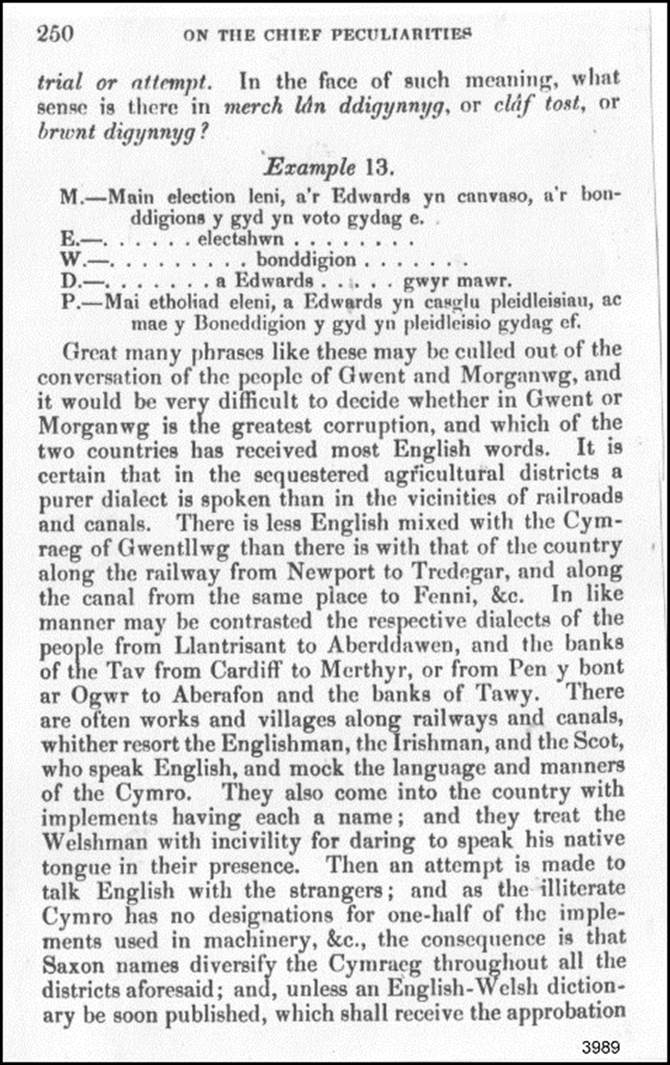

its

meaning being void of

.....

(delwedd 3989) (tudalen

250)

trail

or attempt. In

the face of such meaning, what sense is there in merch lân ddigynnyg,

or clâf tost, or brwnt digynnyg?

Example

13

|

|

|

(There’s an election this year, and Edwards

is canvassing, and all the gentry are voting for him) |

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni river) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

Great many phrases like these may be culled out of the conversation of the

people of Gwent and Morganwg, and it would be difficult to decide whether in

Gwent or Morganwg is the greatest corruption, and which of the two countries

has received most English words.

It is certain that in the sequestered agricultural districts a purer dialect is

spoken than in the vicinities of railroads and canals. There is less English

mixed with the Cymraeg of Gwentllwg than there is with that of the country

along the railway from Newport to Tredegar, and along the canal from the same

place to Fenni, &c.

In like manner may be contrasted the respective dialects of the people from

Llantrisant to Aberddawen, and the banks of the Tav from Cardiff to Merthyr, or

from Pen y bont ar Ogwr to Aberafon and the banks of Tawy.

There are often works and villages along railways and canals, whither resort

the Englishman, the Irishman and the Scot, who speak English, and mock the

language and manners of the Cymro.

They also come into the country with implements having each a name; and they

treat the Welshman with incivility for daring to speak his native tongue in his

presence. Then an attempt is made to talk English with the strangers; and as

the illiterate Cymro has no designations for one-half of the implements used in

the machinery, &c., the consequence is that Saxon names diversify the

Cymraeg throughout all the districts aforesaid; and, unless an English-Welsh

dictionary be soon published, which shall receive the approbation

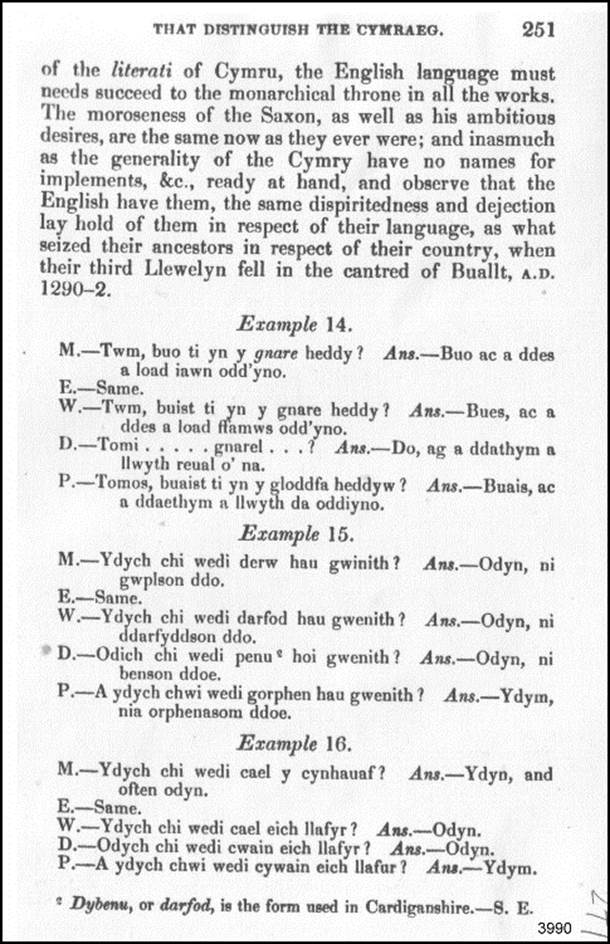

(delwedd 3990) (tudalen

251)

of the literati of

the Cymru (sic), the English language must needs succeed

to the monarchical throne in all the works (= the industrialised valleys and

uplands of the south-east).

The moroseness of the Saxon, as well as his ambitions desires, are the same now

as they ever were; and insomuch as the generality of the Cymry have no names

for implements, &c., ready at hand, and observe that the English have them,

the same dispiritedness and dejection lay hold of them in respect of their

language, as what seized their ancestors in respect of their country, when

their third Llewelyn fell in the cantred of Buallt, A.D. 1290-2.

Example 14

|

|

(Twm, were you in the quarry today?

Yes-I-was, and I brought a good load from there) |

|

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni

river) (Seems to be a misprint for “gware”) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni river

and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. Tomos, buaist ti yn y

gloddfa heddyw? |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

Example

15

|

|

|

(Have you finished sowing wheat? Yes, we

finished yesterday) |

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni river) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

Example 16

|

|

|

(Have you gathered in harvest? Yes ) |

|

|

(1) E. |

(East = the area east of the Rhymni river) |

|

|

(2) M. |

(Middle, = the area between the Rhymni

river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

|

|

(3) W. |

(West = the area west of Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr

/ Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

|

|

(4) D. |

(Dyfed = south-west Wales) |

|

|

(5) P. |

(= “Cymraeg in its purity”, that is,

Standard Welsh) |

...................

(delwedd 3991) (tudalen 252)

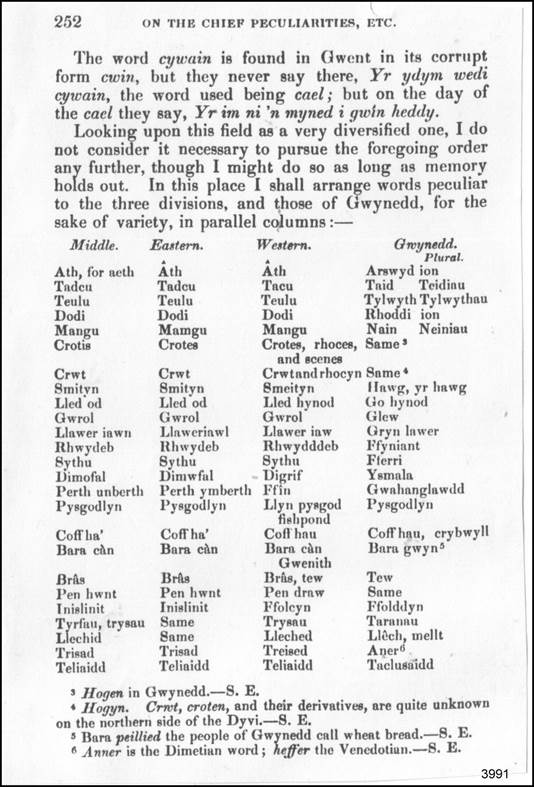

The

word cywain is found in Gwent in its corrupt form cwin,

but they never say there, Yr ydym wedi cywain, the word used

being cael; but on the day of the cael they

say, Yr im ni’n myned i gwin heddy.

Looking upon this field as a very diversified one, I d o not consider it

necessary to pursue the foregoing order any further, though I might do so so

long as memory holds out. In this place I shall arrange the words peculiar to

the three divisions, and those of Gwynedd, for the sake of variety, in parallel

columns: -

(NOTE: The

following table, and the comments made by ‘S.E.’, need to be treated with a

certain amount of scepticism!)

|

W. (West = the area west of

Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Cwm Rhondda / Aber-dâr) |

M. (Middle, = the area

between the Rhymni river and Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr) |

E. (East = the area east of

the Rhymni river) |

Gwynedd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

âth |

ath, for aeth |

âth (= fright) |

arswyd (= fright) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

tacu |

tadcu |

tadcu |

taid (= grandfather) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

teulu |

teulu |

teulu |

tylwyth (= family) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

dodi |

dodi |

dodi |

rhoddi (= to give) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

mangu |

mangu |

mamgu |

nain (= grandmother) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

crotes, rhoces, and scenes |

crotis |

crotes |

same |

|

|

|

|

|

|

crwt

and rhocyn |

crwt |

crwt |

same |

|

|

|

|

|

|

smeityn |

smityn |

smityn |

hawg, yr hawg (= a while) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

lled

hynod |

lled

od |

lled

od |

go

hynod (= quite strange) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

gwrol |

gwrol |

gwrol |

glew (= brave) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

llawer

iaw (sic) |

llawer

iawn |

llaweriawl (sic) |

gryn

lawr (= very many) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

rhwydddeb (rhwydd-deb) |

rhwydeb |

rhwydeb |

ffyniant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

sythu |

sythu |

sythu |

fferi (= freeze, become very

cold) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

digrif |

dimofal |

dimwfal |

ysmala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ffin |

perth

unberth |

perth

ymberth |

gwahanglawdd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

llyn

pysgod, fishpond |

pysgodlyn |

pysgodlyn |

pysgodlyn |

|

|

|

|

|

|

coff

hau |

coff

ha’ |

coff

ha’ |

coff

hau, crybwyll |

|

|

|

|

|

|

bara

càn, Gwenith (= bara gwenith) |

bara

càn |

bara

càn |

bara gwyn (Footnote: Bara peillied

the people of Gwynedd call wheat bread.-S.E.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

brâs,

tew |

brâs |

brâs |

tew |

|

pen

draw |

pen

hwnt |

pen

hwnt |

pen

draw |

|

ffolcyn |

inislinit |

inislinit |

ffolddyn |

|

|

|

|

|

|

trysau |

tyrfau,

trysau |

tyrfau,

trysau |

taranau (= thunderclaps) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

lleched |

llechid |

llechid |

llâch,

mellt (= lightning flashes) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

treised |

trisad |

trisad |

aber (Footnote: Anner is the Dimetian

word; heffer the Venedotian.-S.E.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

teliaidd |

teliaidd |

teliaidd |

taclusaidd |

.....

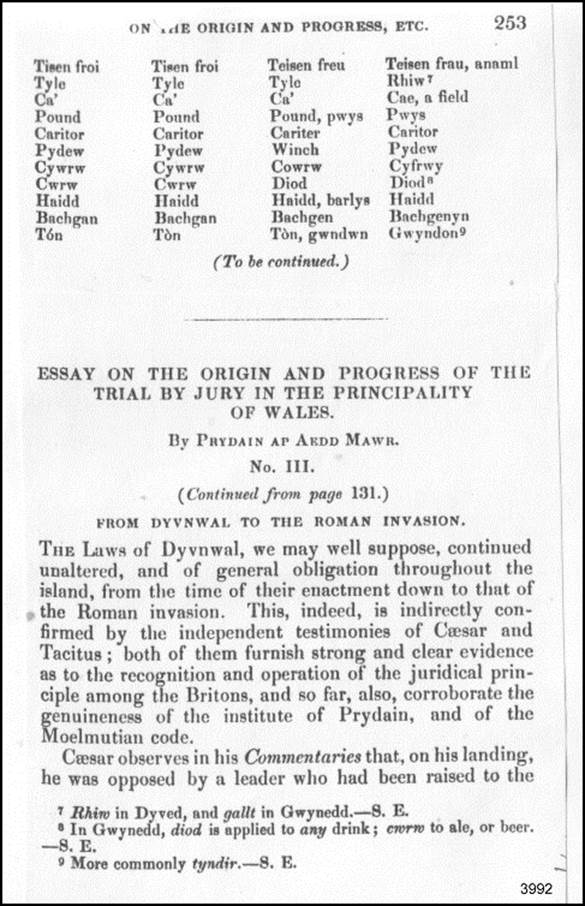

(delwedd 3992) (tudalen

253)

|

|

|

|

|

|

teisen

freu |

tisen froi (in fact, this would be

tishan froi) |

tisen froi (in fact, this would be

tishan froi) |

teisen

frau, anaml (= infrequent) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

tyle |

tyle (in fact, this would be

tyla) |

tyle (in fact, this would be

tyla) |

rhiw (Footnote: Rhiw in Dyved,

and gallt in Gwynedd.-S.E.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ca’ |

ca’ |

ca’ |

cae,

a field |

|

|

|

|

|

|

pound (= pownd),

pwys |

pound (= pownd) |

pound (= pownd) |

pwys |

|

|

|

|

|

|

cariter |

caritor |

caritor |

caritor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

winch |

pydew |

pydew |

pydew |

|

|

|

|

|

|

cowrw |

cywrw |

cywrw |

cyfrwy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

diod |

cwrw |

cwrw |

diod rhiw ( Footnote: In Gwynedd, diod

is applied to any drink; cwrw to ale, or beer..-S.E.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

haidd,

barlys |

haidd |

haidd |

haidd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

bachgen |

bachgan |

bachgan |

bachgenyn |

|

|

|

|

|

|

tón,

gwndwn |

tòn |

tón (sic) |

gwyndon (Footnote: More commonly

tyndir.-S.E.) |

.....

(delwedd

J6262)

The

Cambrian Journal, Volume 4, 1857, 36-38

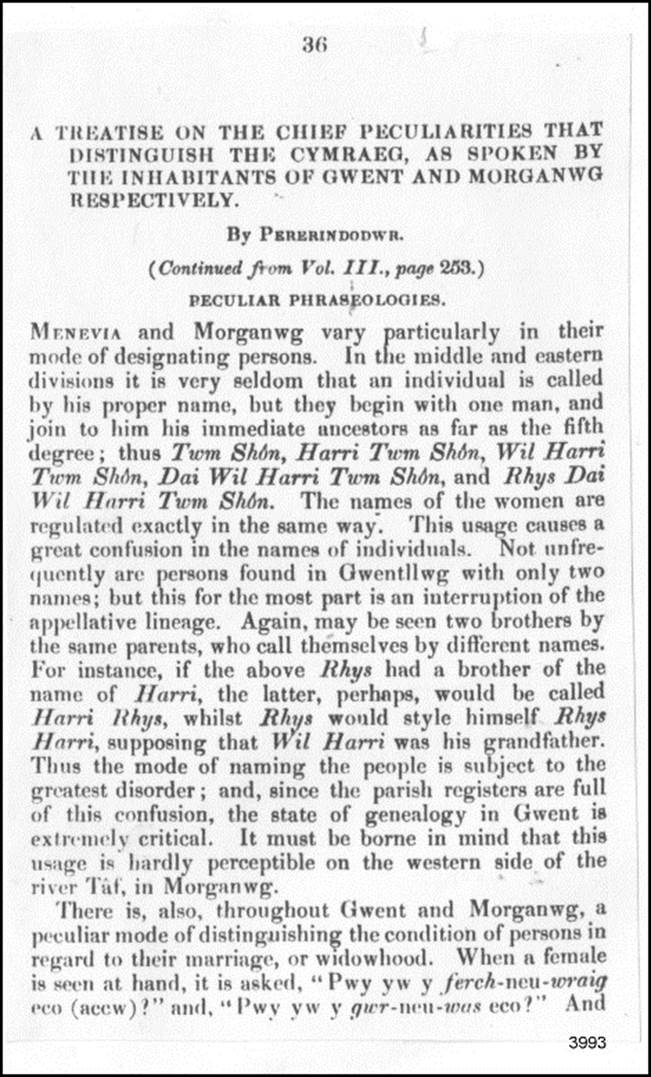

(delwedd 3993) (tudalen

36)

A TREATISE ON THE CHIEF PECULIARITIES THAT DISTINGUISH THE CYMRAEG, AS

SPOKEN BY THE INHABITANTS OF GWENT AND MORGANWG RESPECTIVELY.

BY PERERINDODWR

(Continued

from Vol. III, page 253)

PECULIAR

PHRASEOLOGIES

Menevia and Morganwg vary particularly in their mode of designating persons. In

the middle and eastern divisions it is very seldom that an individual is called

by his proper name, but they begin with one man, and join to him his immediate

ancestors as far as the fifth degree; thus Twm Shôn, Harri Twm Shôn,

Wil Harri Twm Shôn, Dai Wil Harri Twm Shôn, and Rhys Dai Wil

Harri Twm Shôn.

The names of the women are regulated in exactly the same way. This usage causes

a great confusion in the names of individuals.

Not unfrequently are persons found in Gwentllwg with only two names; but for

the most part this is an interruption of the appellative lineage. Again, may be

seen two brothers by the same parents, who call themselves by different names.

For instance, if the above Rhys had a brother of the name

of Harri, the latter, perhaps, would be called Harri Rhys,

whilst Rhys would style himself Rhys Harri,

supposing that Wil Harri was his grandfather. (Thai is, the father is called Rhys and

the grandfather is Harri: one son - Harri - adds his father’s name and is Harri

Rhys; the other son - Rhys - adds his grandfather’s and is Rhys Harri)

Thus the mode of

naming the people is subject to the greatest disorder; and since the parish

registers are full of this confusion, the state of genealogy in Gwent is

extremely critical. It must be borne in mind that this usage is hardly

perceptible on the western side of the river Tâf, in Morganwg.

There is, also, throught Gwent and Morganwg, a peculiar mode of distinguishing

the condition of persons in regard to their marriage, or widowhood. When a

female is seen at hand, it is asked,

“Pwy yw y ferch-neu-wraig eco (accw)?” and,

“Pwy yw y gwr-neu-was eco?”

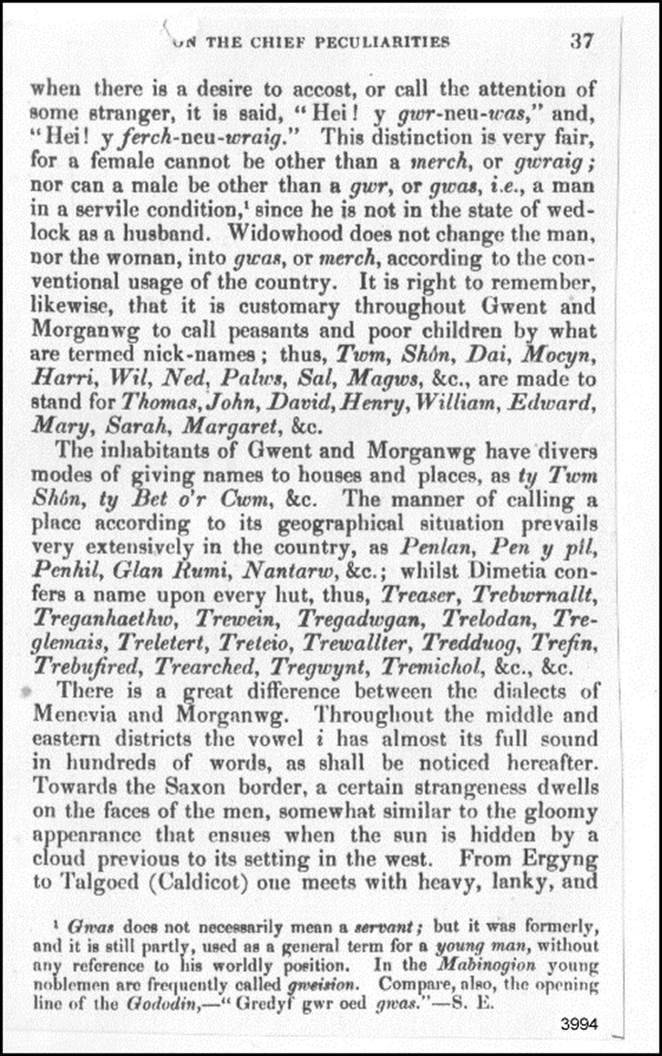

(delwedd 3994) (tudalen 37)

And

when there is a desire to accost, or call the attention of some stranger, it is

said,

“Hei! y y gwr-neu-was,” and

“Hei! y ferch-neu-wraig.”

This distinction is very fair, for a female cannot be other than a merch, or gwraig;

nor can a male be other than a gwr, or gwas; i.e., a

man in a servile condition, since he is not in the state of wedlock as a

husband.

(Gwas does not

necessarily mean a servant; but it was formerly, and it is still partly, used

as a general term for a young man, without any reference to his wordly

position. In the Mabinogion young noblemen are frequently called gweision.

Compare, also, the opening line of the Gododin (sic), - “Gredyf gwr oed gwas.· - S.E.)

Widowhood does not

change the man, nor the woman, into gwas, or merch, according to the

conventional usage of the country. It is right to remember, likewise, that it

is customary throughout Gwent and Morganwg to call peasants and poor children

by what are termed nick-names; thus, Twm, Shôn, Dai, Mocyn, Harri, Wil, Ned,

Palws, Sal, Magws, &c. are made to stand for Thomas, John, David, Henry,

William, Edward, Mary, Sarah, Margaret, &c.

The inhabitants of Gwent and Morganwg have divers modes of giving names to

houses and places, as ty Twm Shôn, ty Bet o’r Cwm, &c. The manner of

calling a place according to its geogrqphical position prevails very

extensively in this country, as Penlan, Pen y pîl, Penhil, Glan rumi, Nantarw,

&c; whilst Dimetia confers a name upon every hut, thus, Treaser,

Trebwrnallt, Treganhaethw, Trewein, Tregadwgan, Trelodan, Treglemais, Treleter,

Treteio, Trewallter, Tredduog, Trefin, Trebufired, Trearched, Tregwynt,

Tremichol, &c., &c.

There is a great difference between the dialects of Menevia and Morganwg.

Throughout the middle and eastern districts the vowel i has almost its full

sound in hundreds of words, as shall be noticed hereafter. Towards the Saxon

border, a certain strangeness dwells on the faces of the men, somewhat similar

to the gloomy appearance that ensues when the sun is hidden by a cloud previous

to its setting in the west.

From Ergyng to Talgoed (Caldicot) one meets with heavy, lanky, and

.....

(delwedd 3995) (tudalen

38)

very ignorant men;

and the old people that are there, especially towards Tre’r Esgob (in modern Welsh Trefesgob, in

English Bishton, 5 miles / 8 kilometres east of Casnewydd / Newport), speak Welsh, which is unintelligible to

the uni-lingual Cymro. They have so much the English accent, and occasionally

an old word like ebargofi , that they cause a mixture of grief

and astonishment in the bosom of the visitor.

When he proceeds from Crughywel to Coed y Cymmer, he hears clearly the accent

and pronunciation of the Brecknockian; ar yr un (? = ), lad (gwlad = contry) raig (gwraig = woman, wife) ferch y forwn ( ?y ferch y forwyn = the miad), &c, present themselves there very

distinctly.

When we go from Coed y Cymmer through Cwmamman to Pont ar Ddulas, we hear the

pronunciation of the Brecknockian, and that of the boys of Caermarthen. Here

the speech becomes vigorous, and the voice thin, and yn wirionedd fach

anwyl i (=

dear me!), thinci

fawr (=

thank you very much) come

to light; and in returning, a change will be perceived towards Margam, and a

little after towards Pont Faen.

Then the body of the country is reached, and the tone becomes slow and grave,

the tongue lisps a little, and the voice is thick. Abertawy, Merthyr, and all

the works (=

the uplands where the iron works were situated), Cardiff and Newport, are

like Van Dieman’s Land. They contain people from every

country (i.e.

all over Wales), and accordingly

one meets in them with the dialects and accents that distinguish every portion

of the inhabitants of the Principality.

.....

Cambrian Journal, Volume 4, Year 1857, pages 207-210

(delwedd 3996) (tudalen

207)

A TREATISE ON THE CHIEF PECULIARITIES THAT DISTINGUISH THE CYMRAEG, AS

SPOKEN BY THE INHABITANTS OF GWENT AND MORGANWG RESPECTIVELY,

BY PERERINDODWR

(Continued

from page 38)

GRAMMATICAL

PECULIARITIES

I will begin with the letters. A is uttered throughout Gwent

to rapidly - too much like ha. B is articulated properly

throughout both provinces; likewise C, Ch, D, Dd. Too much of

the sound H is impatred to E, F, Ff, G, Ng are

pronounced tolerably well; but as for H, it has to answer several purposes. It

is most frequently heard where it stands as an aspirate; but

throughoutthe county of Monmouth it is irregular in hanfon,

haraf, hadref, &c. About half the sound of I is

perceptibly used throughout the middle and eastern divisions in numbers of

words, as

rhiad for rhad (= grace, blessing); so in the following,

Gwiliad (gwyliad

= watch),

Tiad (tad

= father),

Niage (nage

= no),

Rhiaff (rhaff

= rope),

Hiaff (? =

),

Cielwydd (celwydd

= celwydd),

Ciader (cadair

= chair),

Miab (mab

= son),

Biad (bad

= boat),

Griâs (grâs

= grace),

Gwias (gwas

= farm servant),

Miaes (maes

= field),

Cias (cas

= he / she got),

Cieffyl (ceffyl

= horse), &c.

I could not detect any such pronunciation from Penbont ar Ogwr to Pont ar

Ddulas.

L is sounded correctly.

From about Penmarc and Llanddunod to Gwentllwg, Ll is changed,

in respect of sound, to Th, as in arall, which is

pronounced arath.

M,N,O,P,Ph,R,S,T,Th,U,W,Y, are sounded properly, except the last

three.

The aspirate H is frequently associated with W,

as whern for wern, &c.

The O is not quite free from this peculiarity.

The U is generally uttered quite at variance with its proper

pronunciation; indded, it is not often that we can call the sounds of this

vowel singly by their right names, much less its sounds in composition.

Such is the matter in which the Welsh alphabet is vocalised throughout Gwent

and Morgannwg.

ACCENTUATION.-The accents, ascending, descending,

.....

(delwedd 3997) (tudalen 208)

and circumflex, are

as many in both provinces as might be naturally required.

The ascending accent is found in such words as

cymmanfa (=

meeting, association),

diotta (=

drink alcohol),

&c.

the descending in

dilëu (= do

away with);

and the circumflex in

parhâd (=

continuation).

Nature has also taught the inhabitants the proper use of the grave and light

sounds, such as

glàn môr (=

sea side),

glân iawn (=

very pretty);

tòn (=

wave; pastureland) and

tôn (=

tune),

&c.

In like manner, they have learned the mutation of initial consonants, as Bara,

fy mara, ei bara, ei fara (=

bread, my bread, her bread, his bread), &c. All this prevails through both provinces.

NOUN AND ITS NUMBER.- Substantives are pronounced pretty much

alike through all the districts, with the exception of a very slight provincial

drawl.

Angel (=

angel),

gwynt (=

wind),

Tâf (=

river name),

Ffrainc (=

France),

Jerusalem,

dyn (=

man),

coed (=

wood),

mynydd (=

upland), &c.

have all the common and correct articulation. In respect of the singular number

all the provinces are equal, but in reference to the plural, Gwent loses

ground; thus dyn, dynon; offeriad, offerid. Gwent is tolerably well

in brawd, brodyr, bardd, beirdd, &c.

The termination ion is uttered properly in the western

division; the termination au is pronounced wrongly in the eastern division,

where it has the sound like eu, as angeu, dyddieu. The termination od is the

same through both provinces.

The inhabitants say o’n for oen: and in the plural

ŵyn, which is used alike in all divisions.

The plurals of

bran (=

crow),

march (=

stallion),

llestr (=

dish),

collen (=

hazel tree),

plentyn (=

child),

namely brain, meirch, llestri, cyll, plant, are by them pronounced

correctly; but they fail in

merchid ed,

hidden (=

heidden, barleycorn) he,

llysodd oedd,

trad aed,

(what is meant

here it that colloquially merched > merchid, heidden > hidden, llysoedd

> llysodd, traed > tra’d),

the plurals of

merch (=

girl),

haidd (=

barley; barley plants) (in fact the singulative of this word),

llys (=

court),

troed (=

foot)

GENDER OF NOUN.- The masculine and feminine genders are tolerably

consistent with the general rules; but the unknown class is

very irregular. Very often they commit sad mistakes in the gender, and vary

widely from what the grammars teach. Asyn is asen,

and mwlsyn is asyn, always through all the

divisions.

It is not often that they use the word hwrdd, because they

have minharan instead, whilst dafad is used

for the feminine.

The

(delwedd 3998) (tudalen 209)

es is employed pretty correctly, as brenin, brenhines. I

do not remember meeting with a conjunction of name and gender, except in

matters pertaining to the dairy, as hafodwraig and hafodferch.

Many hafottai may be seen throughout Gwent and Morgannwg.

ADJECTIVE.- Under this head the word peth frequently

occurs, as peth drwg, peth mawr, peth gwan, &c.,

throughout both districts. Their mode af rendering an adjective plural is

similar to that which refers to substantives,

llas e,

llison ei ion,

main, minon ei io,

noth, noethion, noithon ei io,

trwm, trymon, trwmon ym io,

bychan, bychin ai,

gwan, gwinid ei ai, &c.

COMPARATIVE DEGREES.- This class is also much in accordance with

nature, and there is considerable accuracy in the arrangement of comparison

throughout the country. Tha positive, comparative and superlative degrees are

found to be tolerably regular, as byr, byrach, byraf; tal, talach,

talaf. They use some that are derived from the comparative, and not

from the positive; as agos, nes, nesaf; the comparitive neasach is

sometimes found in this degree. Again, bach, llai, lleiaf (lliaf).

We have also cyn laned, lled dda, mwy mawr, mwyaf. I know not how

the difference, being so little, between the usages of both provinces on this

head can possibly be described.

PRONOUN.- Through Gwent and Morgannwg no first person

singular other than mi,fi, y, I, is used; and ninau,

which in the plural is pronouced ninâ, and in the singular (!) ni, which is all that is heard in the

several divisions:

In the second person singular we have ti and tithâ, chi and chithâ.

Nyninau and chwychwithau are never heard in the

colloquial converstaion of the people.

The third person singular is efe, ef, hi, fe; seldom or never is

heard anything but nhw in the plural.

In the possessive class the custom is to have fy for the first

person singular, and ein in the plural.

In the second person singular they use dy, ‘th and eith; in

the plural, eich, ‘ch (ych), and eiddoch.

In the third

person singular they use ei and eiddo; in the

plural eu, and sometimes eiddont.

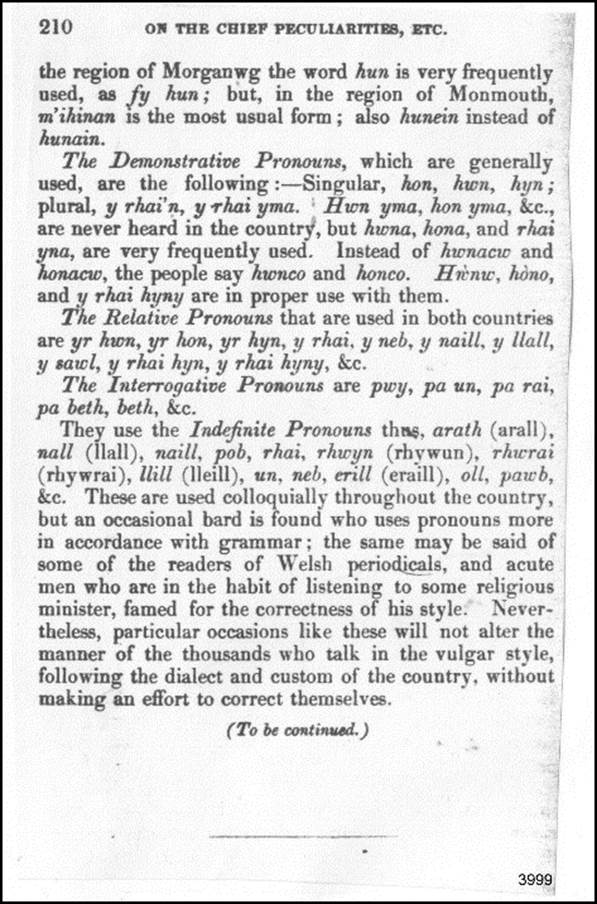

Through

-----

(delwedd 3999) (tudalen 210)

the

region of Morganwg the word hun is very frequently used, as fy hun;

but, in the region of Monmouth, m’ihinan is the most usual

form; also hunein instead of hunain.

The Demonstrative Pronouns, which are generally used, are the

following: -

Singular, hon, hwn, hyn; plural, y rhai’n, y

rhai yma.

Hwn yma, hon yma, &c. are never heard in the country, but hwna, hona and rhai

yna, are very frequently used.

Instead of hwnacw and honacw, the people say hwnco and honco.

Hw`nw, hòno and y rhai hyny are in proper use with

them.

The Relative Pronouns that are used in both countries

are yr hwn, yr hon, yr hyn, y rhai, y neb, y naill, y llall, y sawl, y

rhai hyn, y rhai hyny, &c.

The Interrogative Pronouns are pwy, pa un, pa rai, pa

beth, beth, &c.

They use the Indefinite Pronouns thus, arath (arall); nall (llall), naill,

pon, rhai, rhwyn (rhywun) rhwrai (rhywrai), llill (lleill), un.

neb, erill (eraill), oll, pawb, &c. These are

used colloquially throughout the country, but an occasional bard is found who

uses pronouns more in accordance with grammar; the same may be said of some of

the readers of Welsh periodicals, and acute men who are in the habit of listening

to some religious minister, famed for the correctedness of his style.

Nevertheless, particular occasions like these will not alter the manners of the

thousands who talk in the vulgar style, following the dialect and custom of the

country, without making an effort to correct themselves.

(to be continued)

(Mae’n debyg na

chwblheuwyd mo’r gyfres yn y diwedd. O leiaf, nid wyf wedi dod ar draws y rhan

olynol yn rhifynnau nesa’r cylchgrawn.)

(But it seems

that in fact it never was! I have found no follow-up in further issues of The

Cambrian Journal).

_________

Sumbolau arbennig: ŷ ŵ

Adolygiadau diweddaraf: latest updates:

Sumbolau: ā ǣ ē ī ō

ū / ˡ ɑ æ ɛ ɪ ɔ ʊ ə ɑˑ eˑ

iˑ oˑ uˑ ɑː æː eː iː oː uː /

ɥ / ð ɬ ŋ ʃ ʧ θ ʒ ʤ / aɪ ɔɪ

əɪ ɪʊ aʊ ɛʊ əʊ /

ә

ʌ ŵ ŷ ẃ ŵŷ ẃỳ ă ĕ ĭ ŏ ŭ ẁ ẃ

ẅ Ẁ £

---------------------------------------

Y TUDALEN HWN /THIS PAGE / AQUESTA PÀGINA:

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwenhwyseg/gwenhwyseg_gwentian_dialect_pererindodwr_1856_0959e.htm

Ffynhonnell: nodlyfr 559

Creuwyd / Created / Creada: 01 02 2002?

Adolygiadau diweddaraf / Latest updates / Darreres

actualitzacions: 31-05-2017, 24 07 2000, (cywiro gwallau

teipio - typos corrected), 11-05-2006,

20 07 2002 (cywiro gwallau teipio - typos corrected)

Delweddau / Imatges / Images:

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwenhwyseg/delete_pererindodwr.htm

|

Freefind. |

Ble'r wyf i? Yr ych chi'n

ymwéld ag un o dudalennau'r Wefan CYMRU-CATALONIA

On sóc? Esteu visitant una pàgina de la Web CYMRU-CATALONIA (=

Gal·les-Catalunya)

Where am I? You are visiting a page from the CYMRU-CATALONIA (=

Wales-Catalonia) Website

Weə-r äm ai? Yüu äa-r víziting ə peij fröm dhə CYMRU-CATALONIA

(= Weilz-Katəlóuniə) Wébsait

CYMRU-CATALONIA