|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2863) (delwedd 2863)

|

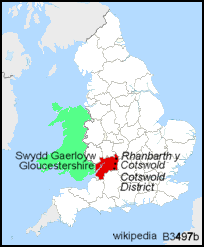

A GLOSSARY OF THE COTSWOLD (GLOUCESTERSHIRE) DIALECT

ILLUSTRATED BY EXAMPLES FROM ANCIENT AUTHORS,

BY THE LATE

REV. RICHARD WEBSTER HUNTLEY, A.M.

OF BOXWELL COURT, GLOUCESTERSHIRE;

FORMERLY FELLOW OF ALL SOULS' COLLEGE, OXFORD;

RECTOR OF BOXWELL AND LEIGHTERTON,

AND VICAR OF ALBERBURY.

LONDON:

JOHN RUSSELL SMITH, 36, SOHO SQUARE.

GLOUCESTER:

EDWARD NEST, WESTGATE STREET.

MDCCCLXVIII.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2865) (delwedd 2865)

|

This being a posthumous Work of the Author's, great difficulty has

been found in editing it correctly; and the reader will kindly make allowance

for any remaining imperfections.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2866) (delwedd 2866)

|

REMARKS

ON THE

COTSWOLD DIALECT.

DIALECT is one of , the best evidences of the origin and descent of the

people who use it; and, whenever we can trace it to its roots, we seem to fix

also the country which supplied the first inhabitants of the region where it

is spoken- Bringing their language with them from the cradle whence they

emigrated, every people brings also its customs, laws, and superstitions: so

that a knowledge of dialect points also towards a knowledge of feelings, seated

(in many cases) very deeply, and of prejudices which sway the mind with much

power; and thus we gain an insight into the genius and probable conduct of any

particular races among mankind.

Another reason, which at this present time renders dialects more worthy of

remembrance, is the universal presence of the village schoolmaster. This

personage usually considers that he places himself on the right point of

elevation above his pupils, in proportion as he distin-

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2867) (delwedd 2867)

|

2 INTRODUCTION.

guishes his speech by classical or semi-classical expressions; while the

pastor of the parish, trained in the schools still more deeply, is very

commonly unable to speak in a language fully " understanded of the

people," and is a stranger to the vernacular tongue of those over whom

he is set so that he is daily giving an example which may bring in a

latinized slip-slop. In addition to this, our commercial pursuits are

continually introducing American solecisms and vulgarisms. Each of these

sources of change threaten deterioration. Many homely but powerful and manly

words in our mother tongue appear to totter on the verge of oblivion. As

long, however, as we can keep sacred our inestimable translation of the Word of

God, to which let us add also our Prayer-book, together with that most

wonderful production of the mind of man, the works of Shakespeare, we may

hope that we possess sheet-anchors, which will keep us from drifting very far

into insignificance or vulgarity, and may trust that the strength of the

British tongue may not be lost among the nations.

It has, moreover, been well observed that a knowledge of dialects is very

necessary to the formation of an exact dictionary of our language. Many words

are in common use only among our labouring classes, and accounted therefore

vulgar, which are in fact nothing less than ancient terms, usually possessing

much roundness, pathos, or power; and, what is more, found in frequent use

with our best writers of the Elizabethan period. The works of Shakespeare

abound in examples of the Cots wold dialect, which indeed is to be expected,

as his connexions and early life are to be found in the districts

--------

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2868) (delwedd 2868)

|

INTRODUCTION.

he spent some part of his younger days in concealment in the neighbourhood of

Dursley, he could not have been better placed to mature, in all its richness,

any early knowledge which he might have gained of our words and expressions.*

This, however, is certain, that the terms and phrases in common use in the

Cotswold dialect are very constantly found in his dialogue; they add much

strength and feeling to it; and his obscurities, in many cases, have been

only satisfactorily elucidated by the commentators who have been best

acquainted with the dialect in question.

The Cotswold dialect is remarkable for a change of letters in many words; for

the addition or omission of letters; for frequent and usually harsh

contractions and unusual idioms, with a copious use of pure Saxon words now

obsolete, or nearly so. If these words were merely vulgar introductions, like

the pert and ever-changing slang of the London population, we should look

upon them as undeserving of notice; but as they are still almost all to be

drawn from undoubted and legitimate roots, as they are found in use in the

works of ancient and eminent authors, and as they are in themselves so

numerous as to render the dialect hard to be understood by those not

acquainted with them, they become worthy of explanation: and then they bring

proof of the strength and manliness of the ancient English tongue, and they

will generally compel us to acknowledge, that while our modern speech may

possibly have gained in elegance and exactness from the Latin or Greek, it

has lost, on the other hand, impressiveness and power.

We believe that the roots chiefly discoverable in this

* See Note at end.

b2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2869) (delwedd 2869)

|

4 INTRODUCTION.

dialect will be the Dutch, Saxon, and Scandinavian; bearing evidence of the

Belgic, Saxon, and Danish invasions, which have visited the Cotswold region.

Occasionally, a Welsh or Gaelic root shows itself, and is probably a

lingering word of the old aboriginal British inhabitants, who were

subsequently displaced by German or Northern irruptions. One or two words

seem to be derived from the Sanscrit, which may have been obtained from our

German relations; one word from the Hebrew may have been left among us when

the Celtic tribes were driven into Wales.

To these old words, now nearly lost in modern conversation, is to be added a

corrupted use of the Saxon grammar; whence modes of expression are produced

which at first sight are obscure, as having never obtained admission in the

colloquy of the better informed, and as being in themselves ungrammatical.

We presume that the most ancient work now extant written in the Cotswold

dialect is the " Chronicle of Eobert of Gloucester," who lived,

according to his own statement, at the time of the battle of Evesham, ie. }

August 4, 1265. This historian and versifier may be said to use altogether the

Cotswold tongue, and his language is that which is still faithfully spoken by

all the unlettered ploughboys in the more retired villages of the

Gloucestershire hill-country. This dialect extends along the Cotswold, or oolitic,

range, till we have passed through Northamptonshire; and it spreads over

Wilts, Dorsetshire, northern Somersetshire, and probably the western parts of

Hampshire. In Oxfordshire the University has considerably weakened the

language by an infusion of Latinisms; and in Berkshire it has suffered still

more by London slang and Cockneyisms.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2869b) (delwedd 2869b)

|

INTRODUCTION. 5

In noticing the change of letters observable in the vernacular tongue on the

Cotswolds, we will begin at the beginning.

A. This vowel, in the first place, frequently receives reduplication; we may

instance " A-ater," for " After." The next change which

this letter admits is into the dipthong M y as in " iEle" for

" Ale f in these cases it is common to have the letter " Y"

placed before the dipthong, as " Ysele;" sometimes so rapidly

pronounced as to sound like the word " Yell," an outcry. "

Lserk" stands for " Lark," the bird; with similar instances of

alteration, which generally are preservations of the Saxon pronunciation.

Next, we find the letter changed into " ai," as in " Make

Maike," " Care Caire;" and where the " ai" is the

legitimate mode of spelling, there it obtains a great elongation of sound, as

"Fair" becomes "Fai-er," "Lair" (of a beast)

"Lai-er"; for this use we have found no authority. Next, the letter

"a" frequently becomes "o," as in " Hand Hond,"

" Land Lond," " Stand Stond," "Man Mon;" the

whole of which are pure Saxon, and are found in constant use by Eobert of

Gloucester. Finally, the dipthong "au" frequently becomes "

aa," as in " Daughter Daater," which is unadulterated Danish; "

Draught Draat," with many other instances. This is also the case where

the letter " a" has properly the sound of this dipthong, as in

"Call Caal," "Fall Vaal," " Wall Waal," and

suchlike words; to these we will add "Law," which is pronounced

" Laa," agreeing with the Saxon " Lah."

B is, as we might expect, sometimes interchanged with P, as in the name of

the plant "Privet," often called "Brivet;" it is also

sometimes, though not frequently, used for W, as " Beth-wind," for

" With-wind," " Edbin" for " Edwin;" "

Bill" for " Will," is common everywhere.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2860) (delwedd 2860)

|

6 INTRODUCTION.

C is changed, occasionally, into G, as for " Crab Grab," "Crisp

Grisp," "Christian Gristin /' "Guckoo" for 1 '

Cuckoo" is universal,but this, like the Scotch " Gowk,"

arises, possibly, from a misapprehension of the note of the bird. In the word

" Yonder," C usurps the place of Y, and the term becomes "

Conder;" this, however, may only be a change from G into C, as the Saxon

word is " Geonda."

E is frequently changed into the dipthong M, as " Beech Beech,"

"Sleep Shep," "Feel Vael," Saxon FaBllan," with many

other instances. It also becomes A short, as "Peg Pag," "Keg

Kag," " Their Thair." Next, by abbreviation, it becomes I, as

"Creep Crip," Saxon, " Crypan," " Steep Stipe,"

Suio-Gothic, " Steypa." When it is in composition with A, it seems

to divide the syllable in which it so stands, as " Beat" becomes

"Be-at," "Death De-ath," Earth Ye-arth," " Tart

Te-art" as applied to the smart of a sore place, or the sharp taste of

an acid, as well as when the substantive, a fruit-pie, is intended. "

Am" becomes " Ye-am;" but here we may observe, that this may

be the Saxon " Eagm," as " Ye-arth" may also come from

the Danish " Jord."

F, as is usual in all languages, often interchanges with V; thus "

Fig" becomes " Veg," " Feed Veed," Dutch "Veedan;"

"Fill Vill," Saxon "Villan;" " For Vor," Dutch

" Ver." This appears to have been our use from the earliest

periods. Eobert of Gloucester gives us " Vut" for "

Foot," " Vant" for "Font," "Ver" for

"For/' "Vail" for "Fall/' with innumerable other

instances; all faithfully followed on the Cotswold range.

G interchanges with Y. This is a custom drawn immediately from the Saxon, in

which language these two letters sometimes appear to be used almost

indifferently.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2871) (delwedd 2871)

|

INTRODUCTION. 7

Thus "Angel" is often pronounced " Any el," "Angelic

Anyelic," or even " Anyely," where the Saxon termination "

lie" or " like" sinks, as in other cases, into the modern

"ly."

H is chiefly remarkable for its wrong position. It is struck off, or put in,

without any authority at the discretion, or rather indiscretion, of the

speaker; only custom seems to have arranged unhappily, that it should appear

where it ought to be absent, and should be wanting where it ought to be

present. "Why 'op ye so, ye 'igh 'ills?" has been heard from

"the priest's lip keeping knowledge." "'Ope" stands for

"Hope," '"Unt" for "Hunt," "Edge" for

"Hedge," "Helm" for " Elm," " Hasp"

or " Haspen," for " Asp" or " Aspen," "

Hexcellent" for "Excellent," " Hegg" for

"Egg," with as many other instances as there may be opportunities

for error. This also seems to have been an ancient practice, as Eobert of

Gloucester is constantly found labouring under this uncertainty; indeed, it

would be difficult to un[der]stand him at all unless this regularity in

mistake on his part is always borne in mind. As an example, we will give his

word " Atom." This is more than a dissyllable, it is two words,

being " At om," contracted from " At ome," and by

supplying the H struck off, we have the sense "At home." But we

must not forget that some of these changes are merely the old Saxon preserved

in its purity: as in the example above, " 'Unt for Hunt," we read

" Ge- untod of Angel-cynne." See " Saxon Chronicle,"

Ingram, Appendix, p. 381.

I interchanges with E, as " Drink " becomes " Drenk," ".

Bring Breng," both being the Saxon pronunciation; as also "Sink

Zenk," " String Strang," " Sting Steng," " Sing

Zeng;" the instances are indeed perpetual, and may

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2872) (delwedd 2872)

|

8 INTRODUCTION.

be generally held to be derived from the Saxon. " Drive " is always

" Dreeve." " Thrive," however, never loses the I; but, as

nature abhors a vacuum, the word is ordained to step into the space which is

vacated by the word ' 'Dreeve," and it usually becomes "

Drive."

M becomes N in the word " Empty," which is pronounced "

Enty," and is the only change of the kind which we have noticed.

commonly usurps the place of A, as we have observed under that letter. It is,

moreover, often changed into " Au," as " Snow " is

pronounced " Snau," " Blow blau," " Mow Mau;"

these sounds have their origin in the Saxon tongue. Sometimes is made into

aa, as in " Croft," which is spoken " Craat " very

frequently, " Moth Maat", Saxon Matha. Lastly, in some words this

vowel changes into A, as in " North," which is frequently

pronounced " Narth."

P, as might be expected, in some cases becomes B, which we have noticed under

that letter.

R is very often misplaced, as " Cruds " for " Curds."

S in like manner suffers from dislocations, thus " Hasp " is "

Haps," " Clasp Claps," * Wasp Waps," with other examples.

This letter is also very frequently made Z, in which we agree with the Dutch,

as in " Sea," " Zee;" and this practice may be as old as

the Belgic invasion of these parts, which is mentioned by Caesar as having

taken place before his age.

T and Th are often changed into D when before the letter R Thus "

Through" becomes "Dru," " Three Dree," '

Trill," and " Thrill Drill," " Thrush " and "

Throstle," "Drush" and "Drostle," "Track"

becomes "Drack," u Tree Dree," "Trash Drash," "

Throw Drow," which also may generally be held to be Dutch usage.

"Th" is

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2873) (delwedd 2873)

|

INTRODUCTION.

9

always pronounced as in the word "This," not as in "Thistle,"

that is, it always has a slight sound of the D before it.

U, sounded hard, takes the place of the double O, as "Brook," which

is pronounced "Bruck," Saxon, Broc, "Book - Buck," Saxon,

Boc, "Look – Luck,” Saxon, Loc, with other instances.

W is often seated so strangely, and sometimes inserted so capriciously into

the interior of words, that, if it is held to be the di-gamma, it might tend

to justify Dr. Bentley in thrusting it, for the versé sake whenever he wants

it, into the middle of Homer's words. We will notice it first as improperly

commencing words; thus, "Oats" becomes "Woats," by

abbreviation "Wuts," "Oaks - Woaks - Wuks," "Home -

Whome - Whum; in the interior of words we have "Go - Gwoa,"

"Going - Gwain," "Stone - Stwon," "Bone - Bwone,"

"Kindle - Kwindle," "Such - Zwitch," with many other

instances. If, however, this letter usurps positions to which it is not

entitled, so it loses also in some cases its natural rights, as "Wool -

Woollen" is often made "Ool - Oollen," "Worsted -

Oosted," "Wolf - Oolf," "Wood - Ood," and thence

sometimes "Hood," with such like instances of deposition. This

elision seems to have a Danish character. Caprice alone appears to have dictated

the erroneous insertions of the letter.

Y claims, and obtains also, a very leading position in the same arbitrary

manner. Thus "Ale" is "Ye-ale," "Health -

Y-ealth," "Earth - Y-earth," "Am - Ye-am,"

"Head - Yead." It suffers, however, total defeat in

"Yes," which is always either "Iss " or "Eece,"

according to the leisure of the speaker.

Z, as we have said, is in constant use for S.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2874) (delwedd 2874)

|

10 INTRODUCTION.

We will now notice some of the contractions in speech which are in constant

use on the Cotswolds. " At," " Atunt," represent, "

Thou art," and "Thou art not/' Fielding, as he places Squire

Western's residence in the north of Somersetshire, very properly bestows on

him a considerable dash of the dialect in question, " I' ool ha'

zatisvaction o' thee," answered the squire, " soa doff thy cloathes,

at-unt half a man," &c. Hist, of a Foundling, book VI., ch. 9.

In the same manner "Cat?" and " Cast?" stand for

"Canst thou?" and "Cass-nt," for " Canst thou

not?"

" D'wye/' imploringly, represents, "Do ye;" as

"D'wunty," "Do ye not."

" Thee bist," is, " Thou beest," "You are."

" Gee-wult?" " Go, will you?" is a term addressed to horses,

when they are to move from the driver; as " K'-mae-thee," M Come

hither," is the term to make them draw nearer.

" Oos-nt,-ootst?" is, " You would not, would you?"

" St-dzign?" is the contraction of " Do you design?"

i.e., " intend." " St-gwain?" " Are you going?"

" St-hire?" is " Do you hear?" " St-knaw?"

" Do you know?" In these and similar instances the " St"

is the termination of "Dost" or "Beest," as the case may

be, and is barely sounded.

" Hae " is, " Have," " Shat " and "

Shat-unt," are, " You shall," and "You shall not."

Squire Western promises Blifil, " I tell thee, shat ha' her to-morrow

morning." Hist, of a Foundling, book VII., ch. 6.

"Te-unt" means, "It is not." "Why-s-'nt?" is

contracted from "Why-oos-nt?" "Why will you not?" as

"Coos-nt" is, " Could you not?"

" 'S-like I shaU " is, " It is likely I shall." "

Said'st thine?"

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2875) (delwedd 2875)

|

INTRODUCTION. 11

" Didst thou say it was thine V " Nar-on " is, " Never a one

"none. " St-Thenk?" is, " Do you think f M E'en as 'twur

" is, " Even as it were." " Med" is, " He might

" "Med, med'nt ur?" represents, "He might, might he not?"

"Mizzomar" for "Midsummer" we should not have introduced,

had it not been that we find this contraction in Bobert of Gloucester, which

seems to give a great antiquity to these abbreviations.

Among variations from Mr. Lindley Murray's English Grammar, we will first

remark that the use of the pronoun " He " is nearly universal. The

feminine " She " is rarely admitted, and the neuter "It"

is equally excluded. " She," when brought into use, is mostly

compelled to submit to an appearance in the accusative case, " Her"

as, by way of example, " Her y-'ent sa' desperd bad a' 'ooman as I've a

knawed," would be very good English on the Cotswold range. It is,

however, very questionable, when the word " He " is used for "

She," whether we have anything more than the Saxon " Heo,"

which is our " She." The dominion, however, of " He "

over " It " is very undoubted, as anything inanimate in itself is

always " He" for instance, a Spade, a Shoe, a Pond, a Gate, a Eoad,

or whatever else presents itself. " He," coming thus into constant

use, suffers from the familiarity when standing before the word "

will" as a sign of the future tense; it then sinks into the vowel "

U " pronounced hard; " u'll die," " u'll vight,"

" u'll stond," " u'll run," are, in such a case, the usual

modes of pronouncing " He will."

" As," in this dialect, obtains very commonly the powers of

"which;" thus, "The 'ooman as I married," "The beast

as I

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2876) (delwedd 2876)

|

1 2 IN TROD TJCTION.

zauld," "The ru-oadas I gade," would be proper phrases in village

colloquy in this district.

" Which," however, takes the place of " When," or "

While " in many cases. As " I bid the wench shou'd hauld awpen the

geat, which she slammed un to, and laughed in muv veace;" " He took

his woath as I layed the dtrap, which I did noa sich a theng."

The plural in " es," so constantly sounded in Chaucer, is still

preserved in many words in this part of the Cotswold range. Thus "

Ghosts " and " Posts " are constantly "Ghostes" and

"Poste's;" "Beasts" are "Beasts," and sometimes

" Beastesses;" " Guests " and " Feasts "

becomes " Guests," and " Feastes:" Addison's joke upon the

songs in the opera,

" When the breezes Fan the treeses," &c.,

would not be discovered to be a satire in the villages under consideration.

There can be no doubt but this is the adherence to ancient usage; and Kemble

was certainly right in considering that Shakespeare intended " Aches

" to be pronounced "Aitches," as a dissyllable, (to which

usage that great actor steadily adhered), because the word was so sounded

down to the days of King Charles II. See Hudibras, passim.

In forming past tenses of verbs we often find words in use, which, if they

ever obtained elsewhere, are now generally obsolete. It is impossible to give

all the instances, but we will enumerate a few specimens. "

Catched" is used instead of " Caught." " Eaught " is

made the perfect tense of " Eeach " this word will appear in the Glossary,

together with Shakespeare's use of it. That

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2877) (delwedd 2877)

|

INTRODUCTION. 13

inimitable poet supports his native dialect in the use of the word "

Holp," as the past tense of " Help." In " Much Ado about

Nothing," act iii., sc. 2., Don John says, " I think he holds you

well, and, in dearness of heart, hath holp to effect your marriage."

This is an ancient form of the word " Help," and kept alive by our

Bible; we find it in Isaiah, xxxi., 3., " He that is holpen shall fall down;"

in Daniel, xi., 34., " They shall be holpen with a little help f in St.

Luke, i. 54., " He hath holpen his servant Israel," and in other

passages; and let us remember that these archaisms now, accidentally but very

happily, increase our reverence for the sacred text.

" Fot," or " Vot," are used as the past tense of "

Fetch f " Give-Gave," makes its past tense in this district "

Gived," but by abbreviation "Gied;" by a farther contraction

spoken " Gid," though, in some cases, the labours of the

schoolmaster and the village Incumbent have advanced the more promising pupil

as far as "Guv." Instances of irregularity in the formation of the

perfect tense are, as we have said, perpetual.

The double negative is very usual, and in this custom Shakespeare frequently

upholds his native district. We will adduce as instances, Henry V., act ii.,

sc. 4.

" Dauphin. Though war nor no known quarrel were in question."

Next, the Two Gentlemen of Verona, act ii., sc. 4.

" Valentine. Nor to his service no such joy on earth."

Measure for Measure, act ii., sc. 1.

" Escalus. No sir nor I mean it not."

Merchant of Venice, act iv., sc. 1.

" Shy lock So I can give no reason nor I will not."

The instances of this irregularity are so frequent with

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2878) (delwedd 2878)

|

14 INTRODUCTION.

this poet, that the reader may readily discover more examples.

The double superlative also obtains a place in our dialect. " Most

worst," or even " Most worstest," would excite no remark as an

unnecessary pleonasm. Shakespeare slips also into this practice: in Henry

IV., Part II, act iii., sc. 1 we find

" King. And in the calmest and most stillest night."

This redundancy gains countenance from the words " Most Highest,"

as applied to the Creator in the Prayer-book version of the Psalms.

The double comparative is also very common. Not only "more better,"

but "more betterer," is usual. Shakespeare has this phrase also in

The Tempest, act i., sc. 2: Prospero says

" Nor that I am more better Than Prospero."

" More braver " also is used in The Tempest, act i., sc. 2.

We constantly use the term " Worser;" and here again we gain

countenance from the same poet. In Hamlet, act iii., sc. 4, this passage

occurs

" Queen. Hamlet, thou hast cleft my heart in twain.

" Hamlet. Oh, throw away the worser part of it, And live the purer with

the other half."

Dryden also supports us in this usage; in the Astrsea Eedux we read at the

3rd line

" And worser far Than arms, a sullen interval of war."

In addition to the plurals in En still retained in English language, which

are Oxen, Brethren, Children, and Chicken, we have in familiar use in our

district the

in the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2879) (delwedd 2879)

|

INT ROD UCTION. 1 5

words u Housen " for Houses, " Peasen " for Peas, and "

Wenchen " for Wenches, " Elmen " for Elm Trees, and "

Plazen " for Places. To these instances, we presume, we ought to add

" Themmen" for Those, "Thairn " for Theirs, " Ourn

" for Ours, " Yourn " for Yours, " Thism " for

These, together with "His'n," "Shiz'n," "

Weez'n," as masculine, feminine, and plural of "His,"

"Hers," and " Ours';" with which irregularity we will

close our notice of our grammatical varieties.

Some of the phrases in frequent use in dialogue on the Cotswolds, which will

appear unusual to a stranger, are as follows:

"A copy of your countenance," means, "you are deceiving,"

" It is not yourseK." Fielding, in his Life of Jonathan Wild, at

the end of chap. 14 of Book iii, uses this expression. " But this he

afterwards confessed at Tyburn was only ' a copy of his countenance.' "

" All manner/' is a phrase used in an evil sense to describe all manner

of annoyance; and is chiefly introduced to describe the carriage of any

person who intrudes himself and acts as rudely as he pleases; thus, " He

came and did all manner," would mean, "all manner of insolence or injury."

Though this idiomatic expression is occasionally used by persons of better

condition, we still do not remember to have seen it in use in any writings of

a light or comic nature.

" All's one for that," means, " notwithstanding your

objection, the case remains the same."

" Drap it, drap it!" that is, " Drop it." This is an

angry request that any course of annoying remarks or practices may cease; and

it may be safely concluded, when a genuine

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2870) (delwedd 2870)

|

16 INTRODUCTION.

son of the Cotswolds uses this phrase, that his patience is just worn out.

" Gallows bad," " Gallows drunk," " a Gallows cheat

" always pronounced "Gallus" means, "bad enough for the gallows."

It is possible that this may be a term of great antiquity, and may draw its

frequent use from the gallows-tree of the feudal lord.

" Hand over head " is a metaphor taken from the conduct of a mob in

a battle or in aggressive confusion, and is used to express anything done in

haste, ill-order, and self-impeding perturbation. This phrase occurs in

Farquhar's comedy, where Pindress, the maid-servant, urging the Page to marry

her on the spot, exclaims, " No consideration! This business must be

done hand over head." Whereas, to do anything " with a high hand

" always implies that it was some attempt triumphantly carried through.

" I cannot away with," is an ancient phrase, constantly found in

the Bible, and still therefore in frequent use in this simple district,

meaning, "I cannot cast away the recollection of it," 1 cannot

endure it." It is used when speaking of some misfortune or bad conduct.

See Isaiah, L, 13.

" I'll tell you what," is as much as to say, " I will give you

an unanswerable argument;" sometimes it means, * I will give you my

fixed resolution." Shakespeare perpetually uses this phrase; as an

instance we may turn to Henry IV., Part I., act iii., sc. 1.

" Hotspur. I'll tell you what,

He held me, but last night, at least nine hours."

" It'll come right aater a bit," means, " the difficulty in any

business is passing away."

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2881) (delwedd 2881)

|

INTRODUCTION. 17

" I can't be off it," means, " an irresistible impulse compels

me to it," " I must do it."

" Let alone," is a statement that some necessary characteristic in

any circumstance need not be taken into present calculation, as " A

broken leg is zitch a hindrance, let alone the anguish of un!"

" May be" is continually used for " Perhaps " it is the French

" Peut-6tre."

" Month's mind," means, a mind unsettled on any particular plan, a

weak resolution. It is a term derived from a custom observed in the obsequies

of remarkable persons previous to the Eeformation. At the end of the month after

the funeral there was a minor ceremony performed in recollection of the

deceased, and which was intended to keep him in mind. A less procession, a

less dole, and a less religious service took place; and, as these observances

were all weaker in effect, and were necessarily of a very evanescent

character, so any poor and wavering feeling came to be compared to " the

month's mind " after a stately funeral. Thomas Wyndesor, Esq., in his

will dated August 13, 1479, gives particular directions as to his funeral,

which were designed with a view to very considerable state and dignity, and

at the end of these is the following: " Item I will that there be one hundred

children, each within the age of sixteen years, at my month's mind, to say

our Lady's Psalter for my soul in the church of Stanwell, each of them having

iiiid. for his labour, and that before my month's mind the candles burnt before

the rood in the said church be renewed and made at my cost; Item I will that

at my month's mind my executors provide twenty priests, besides the clerks

that come to sing Placebo, Dirige, &c, &c." Testamenta Vetusta,

c

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2882) (delwedd 2882)

|

18 INTRODUCTION.

p. 393, in which work this practice is often alluded to. Ii Machyn's Diary

this custom is also frequently noted; w< will extract from it the notice

of the deaths and month' mind of the two Dukes of Suffolk, who died whil children,

of the sweating-sickness. " The xxii day ot September (1551) was the

Monyth's Mind of the ii Dukke of Suffoke in Chambryge-shyre, with ii

Standards, ii baners- grett of Amies and large, and baners rolls of Dyver

Armes with ii Elmets, ii (swords), ii Targetts crowned, ii Cotes o Armes, ii

Crests, and ten dozen of Scochyons crowned; ant yt was grett pete of their

dethe, and yt had plesyd God of so nobull a stok they wher, for ther ys no

more of them left."

" Next of kin " does not mean relationship in blood, but any

similarity. " Fainting " would be " next of kin to death/' "

A Glove next of kin to the Hand;" " Fluid white- wash" would

be " next of kin to Milk;" it means also any near relationship in

place or authority; thus, a " Justice of the Peace " would be

" next of kin to a Judge," an " Arch-deacon" to "the

Bishop," a "Lord-Lieutenant" to "the Monarch."

" Overseen" and "overlooked" means "bewitched" led

astray by evil influence, as having suffered under the " Evil Eye"

of a witch or wizard. Thus, " I was quite overseen in that matter,"

means, " I had lost my reason by some evil agency."

" Play the bear," or " play the very Buggan witlj you is to

spoil, to harass; " Buggan " meaning Satan or any evil spirit

" Old Bogey."

" Poke the Fire," is always used instead of " Stir the Fire/ and

rightly, as having reference to the poker.

" Quite natural," means anything done easily, as a mattei

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2883) (delwedd 2883)

|

INTRODUCTION. 19

of course, and is spoken of proceedings which are quite artificial thus a man

would be said to fly up in a balloon " quite natural."

" She is so/' means a female expects to become a mother; probably this

delicate phrase was originally accompanied with a position of the hands and

arms in front of the person speaking, indicative of a promising amplitude.

"To and again," to move backwards and forwards, to go to a certain

point and to return again, as on a terrace-walk in a garden. " To and

fro " being, in fact, the same idea.

"You are such another," is a phrase used in derogation. " You

are as bad as the preceeding." We find this phrase in Much Ado about

Nothing, act. iii. sc. 4. "Margaret Yet Benedict was such another, and

now he is become a man."

" You'll meet with it," is a threat that punishment will unavoidably

follow the course which is being pursued by the person addressed; the pronoun

" it" being the abbreviation for chastisement.

" You might as well have killed yourself," is used to describe an

accident which might have produced death, meaning " You have done enough

to have killed yourself."

" You are another guess sort of a man," means " You differ

from the example before us." Probably the word " Guess" in

this phrase was originally " Guise."

" Whatever" frequently ends a sentence prematurely, the words

" may happen," or " by any means," being struck off. It

is mostly used negatively, as " I would not do it, whatever."

" He would not help himself, whatever." This phrase, in spite of

the ludicrous effect which attends it, is sometimes heard in the better walks

of life in the Cotswolds.

c 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2884) (delwedd 2884)

|

20 INTRODUCTION.

We hardly know whether we ought to notice slip-slop, or the mistaken use of

words introduced by the schoolmaster; we will, however, remark that the

phrase " It don't argufy," " edify," or "

magnify," stands, whichever verb is selected, for " it does not

signify." And when the honest rustic intends to be very emphatical and

dignified at the same time he will frequently use all three errors; and

having thus enriched his vocabulary with so many synonyms for "

signify," he casts away the right word as being utterly useless.

The habit, however, of substituting the word "Aunt" for "

Grandmother," which is very common in this district, deserves

consideration, because we find this use of the word twice in Shakespeare. In

Othello, act i. sc. 1, Iago alarms Brabantio with the intelligence of the

elopement of his daughter with the Moor, whom he styles a " Barbary horse,"

and adds " You'll have your nephews neigh to you," meaning

grandsons; so again in Richard III., act iv. sc. 1, we have the stage

direction "Enter Queen, Duchess of York, and Marquis of Dorset, at one

door; Anne Duchess of Gloucester, leading Lady Margaret Plantagenet,

Clarence's youngest daughter, at the other" The Duchess of York addresses

Lady Margaret with the words " Who meets us here? My Niece

Plantagenet," whereas she is her granddaughter. The grandmothers

sometimes seem to take offence if they are denominated by any more ancient

appellation than " Aunt" among their grandchildren.

The tone in which the Cotswold dialect is spoken is usually harsh, and the

utterance is rapid, so that the conversations between the natives, marked by

continual contractions, hasty delivery, and unusual words, is hardly understood

by a stranger.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2885) (delwedd 2885)

|

INTRODUCTION. 21

In presenting the reader with the Glossary which follows, we endeavour to

give the derivation of each word from its original root, whenever we think we

can suggest it with probability. In addition to this, where we can find the

use of any word now nearly or quite lost, we have offered the quotation.

These quotations we have, in most cases, verified; where we have not done

this, we have adopted them chiefly on the authority of the Encyclopedia

Londinensis.

These extracts from ancient writers, all, more or less, of authority, will

show that the old Gloucestershire words are not mere vulgarisms, but though

now seldom or never used, are as well, if not better founded than those in common

parlance; and it will be seen, in not a few instances, that the English

language has lost rather than gained by adopting Latinisms in their stead.

We wish farther to remark that some of the words found in the following

Glossary are not, strictly speaking, dialectical, but only still in continual

use in this district, while they are dying rapidly in other places. As an

instance, the word " Wag" appears in the Glossary. Now this word,

in spite of the Scriptural use of it, as in the phrase " Wagging their

heads," and in other passages, is almost limited to the motion of a

dog's tail, while on the Cotswolds its general application is still

preserved. A person who was standing in obstruction of any necessary work,

would be addressed by the phrase " Why-'s 'nt Wag?" "why do

you not move?" Such words are inserted to prolong the memory of terms,

in themselves original and powerful, but which appear to be endangered by the

use of words, more new but weaker, and drawn from a less efficient

vocabulary.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2886) (delwedd 2886)

|

NOTE.

Nothing will need an apology which may tend to throw a light on any part of

the life of Shakespeare. We will therefore without further preface, offer the

following matter, kindly supplied to us by a friend residing at Dursley. We

may take it for granted that the tradition which states how the young poet

fled before the enraged face of Sir Thomas Lucy, on account of some illegal

intrusion in the knight's park in Warwickshire, is based on some fact. It is surmised

that he sought shelter in Dursley, a small town seated .on the edge of a wild

woodland tract. Some passages in his writings show an intimate acquaintance

with Dursley, aud the names of its inhabitants. In the Second Part of Henry

IV., act v. sc. 1, * Gloucestershire," Davy says to Justice Shallow

"I beseech you, Sir, to countenance William Visor of Woncot, against

Clement Perkes of the Hill.'' This Woncot, as Mr. Stevens, the commentator,

supposes, in a note to another passage in the same play (act v., sc. 3) is

Woodmancot, still pronounced by the common people "Womcot," a

township in the parish of Dursley. It is also to be observed that in

Shakespeare's time a family named Visor, the ancestors of the present family

of Vizard, of Dursley, resided and held property in Woodmancot. This township

lies at the foot of Stinchcombe Hill, still emphatically called " The

Hill " in that neighbourhood on account of the magnificent view which it

commands. On this hill is the site of a house wherein a family named "

Purchase," or " Perkis," once lived, which seems to be identical

with " Clement Perkes of the Hill." In addition to these coincidences,

we must mention the fact that a family named Shakespeare formerly resided in

Dursley, as appears by an ancient ratebook, which family still exist, as

small freeholders, in the adjoining parish of Bagpath, and claim kindred with

the poet. A physician, Dr. Barnett, lately residing in London, and who died

at an advanced age, was in youth apprenticed at Dursley, and had a vivid

remembrance of the tradition that Shakespeare once dwelt there; he affirmed, that

losing his way in a ramble in the extensive woods which adjoin the town, he

asked a person whom he met where he had been, and was told that the name of

the spot which particularly attracted his attention was called "

Shakespeare's walk." In the play " King Richard 11.^ act ii. sc.

3," a description of Berkeley Castle is given, which is so

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2887) (delwedd 2887)

|

INTRODUCTION. 23

exact that it is hardly possible to read it without considering it as if seen

from Stinchcombe Hill. The scene is "A Wild Prospect in Gloucestershire.

" Bolingbroke and Northumberland enter; Bolingbroke opens the dialogue:

" How far is it, my lord, to Berkeley, now? North. I am a stranger here

in Gloucestershire; These high wild hills and rough uneven ways Draw out our

miles, and make them wearisome." " But, I bethink me, what a weary

way From Ravenspurg to Cots wold will be found In Ross and Willoughby wanting

your company," &c. Enter to them Harry' Percy, whom Northumberland

addresses: " How far is it to Berkeley? And what stir Keeps good old York

there, with his men of war? Hotspur. There stands the castle by yon tuft of

trees." Now this is the exact picture of the castle as seen from "

The Hill;" the castle having been, from time immemorial, shut in on one

side, as viewed therefrom, by an ancient cluster of thick lofty trees.

Lastly, we would add that down to the reign of Queen Anne the Cotswold range was

an open tract of turf and sheep-walk, which extended up into Warwickshire,

and was famous as a sporting-ground, particularly for coursing the hare with

greyhounds, throughout the whole extent. It was consequently well-known by

the gentry of both counties; and this is evidenced by their pedigrees,

wherein intermarriages between the houses of each county are frequently

found. The portion of Shakespeare's life which has always been involved in

obscurity is the interval between his removal from Warwickshire and his

arrival in London; and this period, we think, was probably spent in a retreat

among his kindred at Dursley, in Gloucestershire

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2888) (delwedd 2888)

|

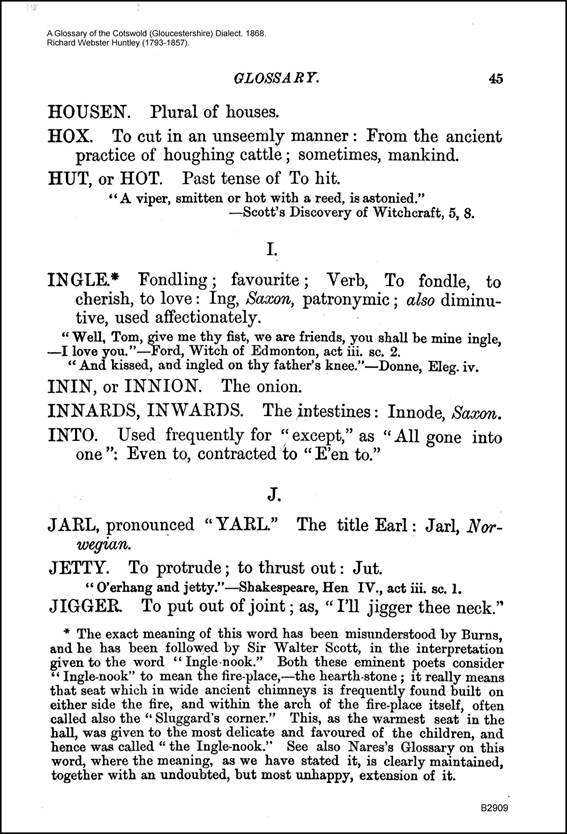

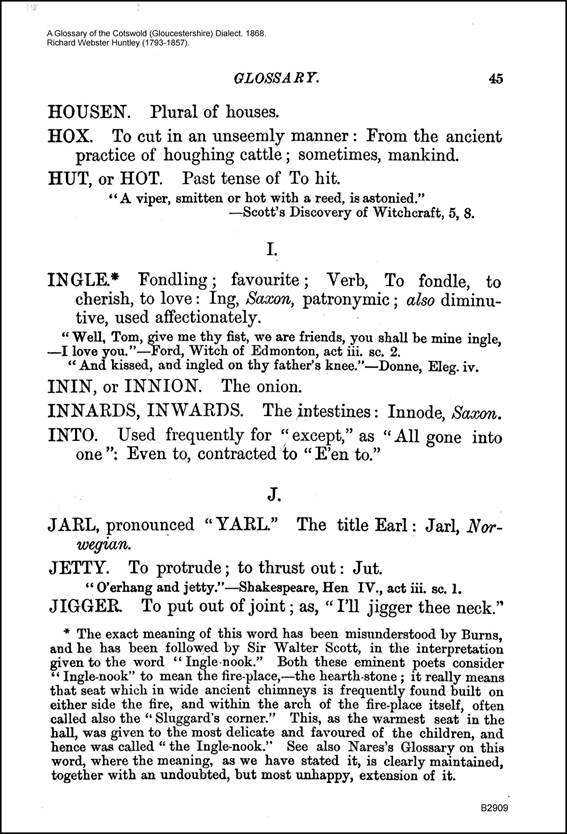

GLOSSARY.

A-ATER. After, in point of time; also, according to, in

point of manner: " Aater this fashion." ABIDE. To endure, to

suffer: Abidian, Saxon.

"The nations shall not be able to abide his indignation." Jer. x.,

10. "The day of the Lord is great and very terrible, and who can abide it."

Joel ii., 11.

Used in the same sense by Robert of Gloucester and Peter Langtoft.

ADRY. Thirsty: Adrigan, Saxon. AFEARED. Frightened: Afa3ran, Saxon.

" Whether he ben a lewde" or lered, He n'ot how sone that he may

ben affered."

Chaucer, Doctor's Tale, 1. 1221. See also Spenser's Fairy Queen.

AFORE, ATVORE. Before: Atforan, Saxon.

AGEK Opposite to, over against. This word is also used to designate any given

time for the occurrence of an event, or the performance of a promise: Agen,

contra, Saxon.

" I'll be ready agen Zhip-Zhearin," or " Luk for't agen

Mi-elmas." Even agen France stonds the contre of Chichestre,

Norwiche agen Denemarke," &c, &c. Robert of Gloucester. Hearne's

Edition, 1714, Vol. I., p. 6.

ANEAL. To mollify, to shape by softening.

u Thus was I, sleeping, by a brother's hand Of life, of crown, of queen, at

once dispatched; Cut off even in the blossoms of my sin, Unhouseled,

disappointed, unanealed."

Shakespeare's Hamlet, act i. sc. 4.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2889) (delwedd 2889)

|

G GLOSSARY.

See also the receipt for "Anealing your Glass" when "you would

paint there." Peacham's Compleat Gentleman, Vol. II., lib. I., p. 96.

ANEAWST, ANNEARST, ANIGSHT. Near; also, metaphorically, resembling: Near,

Saxon.

" Host. Will you go an-heirs? Shallow. Have with you, mine host."

Shakespeare Merry Wives of Windsor, act ii. sc. i.

ANTJNST. Over against, opposite to: Nean, Saxon.

ARTISHREW. The shrew-mouse, an animal used in magical charms: "

Shrew," and " arte " to compel, Sir Walter Scott writes,

Scottice, " Airt."

" A tiraunt would have artid him by paynes." Bootius, MS. Soc.

Antiq. 134, f. 296.

ATHEKT. Athwart, across: Thwur, Saxon.

" All athwart there came A post from Wales, laden with heavy news."

Shakespeare, King Hen. IV.

ATTERMATH. Grass after mowing: After" and " Math," from

Mathan, Saxon, to mow.

AWAY WITH. To bear with, to suffer, to endure.

" Shallow. She never could away with me Falstaff. Never never; she would

always say, she could not abide Master Shallow." Shakespeare, Henry IV.,

Part II.. act iii. sc. 2.

" The new moons and sabbaths, the calling of assemblies, I cannot away with."

Isaiah i. 13.

" Moria. Of all the nymphs i' the court, I cannot away with her; 'tis

the coarsest thing!" Ben Jonson, Cynth. Revels, act iv. sc. 5.

AXE. To ask: Axian, Saxon.

" Axe" not why; for though thou ax 4 me, I woll not tellen Godde's

privetee." Chaucer's Miller's Tale, 1. 3557. " What is this to

mene, man, maiste thee axe." Deposition of Ric. ii.

AX EN. Ashes; also in the sense, cineres: Axan, Saxon.

" Yn'ot whareof men beth so prute, Of erthe and axen, felle and bone, Be

the soule's enis ute, A viler carsang n'is there none." Song temp. Edw.

I.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2890) (delwedd 2890)

|

GLOSSARY. 27

B.

BACK-SIDE. The backfront of a house.

" He led the flock to the backside of the desert." Exodus iii. 1.

BAD. To beat husks, or skins of walnuts, or other fruits:

Battre, French. BAG. The udder of a cow; also a sack.

BALD-EIB. The piece otherwise called the " spare-rib," because

moderately furnished with meat.

BANDOEE. Violoncello or bassoon: Pandura, a similar Italian instrument.

BANGE. A gamekeeper's word, to express the basking and dusting themselves by

feathered game.

Bang-a-bonk to lie lazily on a bank. Halliwell's Dictionary.

BAN-NUT. The walnut: Baund, swelling, DarasA; Thnut, Saxon.

BABKEN, BARTON. The homestead: Bairton, Goth, to guard.

" I were never af eared but once, and that ware of grandfar's ghost, for

he always hated I, and a used to walk, poor zoul, in our barken." Mrs.

Centlivre, Chapter of Accidents, act ii. sc. 1.

BAEM. Yeast: Beorm, Saxon.

"And sometimes make the drink to bear no barm." Shakespeare, Midsum.

Night's Dream, act ii. sc. 1.

BAEEOW-PIG. The hog, a gelt Pig: Barren?

BASS OR BAST. Matting used in gardens.

BASTE. To beat: Bastre, old French.

BAT-FOWLING or BAT-BIEDING. Taking birds by night in hand-nets.

" Sebastian. We would so, and then go bat-fowling." Shakespeare, Tempest,

act ii. sc. 1.

BAULK. A bank or ridge: Bale, Saxon.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2892) (delwedd 2892)

|

28 GLOSSARY.

" And as the plowman, when the land he tills, Throws up the fruitful

earth in rigged hills, Between whose chevron form he leaves a balke, So

'twixt these hills hath nature framed this walke,'

Browne, Brit. Pastorals, i. 4.

BEASTS. Horned cattle. BEHOLDEN. Indebted to. BELLY. A verb. To swell out. BELLUCK.

Bellow: Bellan, Saxon.

"As loud as belleth winde in hell." Chaucer, House of Fame, i 713.

BENNET, BENT. Dry, standing grass: Biendge, Teuton

" The dryvers thorowe the woode*s went For to rees the deer, Bowmen

bickered upon the bent With their browde arrowes clear. " Chevy Chase.

BESOM. A word of reproach, applied solely to the fair sex; as, " Thee

auld besom:" Perhaps derived from the besom on which a witch rides; but

very likely the same word with "bison," which, in the northern

dialects, means a shame or disgrace; a woman doing penance was called a

" holy bison." See Brockett's Glossary.

BETEEM. To indulge with: Toeman, Saxo7i.

" So would I, said the Enchanter, glad and fain

Beteem to you his sword." Spenser. " Belike for want of rain, which

I could well Beteem them from the tempest of mine eyes."

Shakespeare, Midsum. Night's Dream, act i. sc. 1. " That he might not

beteem the winds of heaven Visit her face too roughly." Shakespeare,

Hamlet, act i. sc. 2.

BIDE. To stay, to dwell: Bidon, Saxon.

" Pisano. If not at court,

Then not in Britain must you bide."

Shakespeare, Cymbeline, act iii. sc. 2. " All knees to Thee shall bow of

them that bide In heaven, or earth, or under earth in hell." Milton.

BIN. Because: contracted from " It being."

" Leon. Being that I flow in grief,

The smallest twine may lead me." Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing,

act iv. sc. i.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2893) (delwedd 2893)

|

GLOSSARY. 29

" La-poope. And being you have declined his means, you have increased

his malice." Beaumont and Fletcher, Honest Man's Fortune, act ii.

BITTLE. Beetle, a heavy mallet used to ram down pavements, &c.: Bitl,

Saxon.

" Fatstaff.li I do, fillip me with a three-man beetle."

Shakespeare, Henry IV., Part II., act i. sc. 2.

BLATHEB. To talk indistinctly, so fast as to form bladders at the mouth.

BLIND-WOBM. A small snake, the slow-worm.

" Adder's fork and blind-worm's sting." Shakespeare, Macbeth, act iv.

sc. 1.

BLO WTHE. Blossom in orchards, bean fields; cinquefoin, &c.: Blawd,

Welsh.

" Ambition and covetousness being but green and newly grown up, the

seeds and effects were as yet but potential, and in the blowth and bud.

"--Sir Walter Raleigh.

BODY, An individual; often spoken of oneself, " A body can," or

" A body can't."

" Good may be drawn out of evil, and a body's life may be saved without

any obligation to the preserver." Sir Roger L'Estrange.;

BOOT. Help, defence: Bot, Saxon.

"Then list to me, St. Andrew be my boot. Pinner of Wakefield, iii. 19.

See also Old Ballads, and Shakespeare, passim.

BOTTOM. A valley.

" Dunster Toun stondithin a bottom " Leland's Itinerary. "

Hot. It shall not wind with such a deep indent, To rob me of so rich a bottom

here."

Shakespeare, Henry IV., Part I., act iii. sc. 1. u Pursued down into a little

meadow which lay in a bottom." Autobiography of King James II., Vol. I.,

p. 213.

" On both the shores of that beautiful bottom." Addison, Remarks on

Italy, 5th Ed., p. 152.

BBAKE. A small coppice: Brwg, Welsh.

" Escalus. Some run through brakes of vice."

Shakespeare, Measure for Measure, act ii. sc. 1. " 'Tis but the fate of

place, and the rough brake That virtue must go through."

Id., Henry VIII., act i. sc. 2.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2894) (delwedd 2894)

|

30 GLOSSARY.

BRASH. Light, stony soil: Trash?

BRAVE. Healthy, strong in appearance.

11 A brave vessel,

Who had, no doubt, some noble creatures in her, Dashed all to pieces."

Shakespeare, Tempest, act i. sc. 2.

BEAY. Hay spread abroad to dry in long parallels: Breed, Saxon.

BEEEDS. The brim of a hat: Breed. Sax, as laid out flat.

BEIM, BEEM. Spoken of a sow, as also of a harlot: Bremen, Ardere desiderio,

Teut.

Peter Langtoft uses this word in the sense "furious."

BRIT. Spoken of the shedding of over-ripe corn from the ear. Chaucer's word

" bretful " is probably " full to bretting." It seems the

root of "brittle."

" His wallet lay before him in his lappe

Bret-ful of pardon, come from Rome al hote."

Chaucer, Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, 1. 689. *' A mantelet upon his

shoulders hanging Bret-ful of rubies red, as fire sparkling."

Id., The Knighte's Tales, 1. 2166. " They blew a mort upon the bent, They

'sembled on Sydis sheer, To the quarry the Percy went,

To see tbe brittling of the deer." Chevy Chase. " With a face so

fat As a full bladere Blowen bret-ful of breth."

Creed of Piers Plowman, 1. 443.

BEIZZ, BEEEZE. The gad-fly: Briosa, Saxon.

" The herd hath more annoyance from the breeze, Than from the

tyger."

Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, act i. sc. 3.

BEOOK. To endure, to bend to opposition or evil: Brucan, Saxon.

" Heaven, the seat of bliss,

Brooks not the works of violence or war." Milton.

BEOW. The abrupt ridge of a hill: Brcew, Saxon.

" And to the brow of heaven

Pursuing, drave them out from God and bliss." Milton.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2895) (delwedd 2895)

|

GLOSSARY. 31

"And after he had upon the brow of the hill raised breastworks of faggots."

Lord Clarendon, describing the battle of Lansdown.

BROW. Adjective. Brittle, liable to snap off suddenly: Brau, Welsh.

BUCKING. The foul linen of a household collected for washing: Buc, Saxon;

Lagena?

"Throw foul linen upon him, as if it were going to bucking."

Shakespeare, Merry Wives of Windsor, act iii. sc. 3.

BUDGE. To move a very short distance: Bugan, Saxon; Buj, Sanscrit.

BUFF. To stammer: derived from the sound.

BULL-STAG. A bull castrated when old.

BURNE, BURDE. Spoken of as much hay or straw as a man can carry: Bwrn, Welsh,

a truss.

BURR. Pancreas of a calf, the sweet-bread: Bourre, French.

BURROW. Any shelter, especially from weather: Burh, Saxon.

BUTT Y. A comrade in labour: Bot, Saxon.

C.

C ADDLE. To busy with trifles; to confuse; to vex: Caddler is, we believe,

Old French, with the same sense.

CADDLEMENT. A trifling occupation; confusion; vexation.

GANDER. Yonder: Geonda, Saxon.

CANDER-LUCKS. Look yonder.

CANDLE-MASS BELLS. The snowdrop.

CANDLE-TINNING. Candle-lighting; evening: Tinan, Saxon, and candle.

" Love is to myne harte gone, with one spere so kene,

Night and day my blood it drynks, mine herte doth me tene."

MS. Harl. Miscell.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2896) (delwedd 2896)

|

32 GLOSSARY.

" The priests with holy hands were seen to tine

The cloven wood, and pour the ruddy wine." Dryden. " Spiteful Atin,

in their stubborn mind, Coals of contention and hot vengeance tined."

Spenser's Fairy Queen. "Kindle the Christmas brand, and then To sunset

let it burne; Which quencht, then lay it up agen Till Christmas next

returne." "Part must be kept wherewith to teend The Christmas log

next yeare; And where 'tis safely kept, the fiend Can do no mischief

there." Herrick.

CANT. To toss lightly, to cast anything a small distance.

CAEK. Care: Care, Welsh.

CESS. A word used in calling dogs to their food. Probably in monastic halls

the portions assigned to the brotherhood were originally called cessions, and

the word was jocosely transferred afterwards to the knight's kennel: Cessio,

Latin.

" The poor jade is wrung in the withers out of all cess." Here the

word means " out of all measure." Shakespeare, Hen. IV., Part L,

act ii. sc. 1.

CHAM. To chew: Cham, Sanscrit (?) to eat.

CHAK, or CHIR. A job; hence charwoman: either Jour, French, as hired by the

day, or Cyrre, Saxon, labour.

" And when thou'st done this chare, I'll give thee leave To play till

Doomsday."

Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra, act v. sc. 2.

CHARM. A noise; a clamour: Cyrm, Saxon.

CHATS. The chips of wood when a tree is felled.

CHAUDRON. Entrails of a calf; metaphorically, any forced meats or stuffing put

in the crops of birds sent to table: Caul, Welsh (?)

"Add thereto a tyger's chawdron." Shakespeare: Macbeth, act i v. sc.

1.

" Swan with chaudron." Relation of the Island of England by an Italian,

a.d. 1500, note 79.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2897) (delwedd 2897)

|

GLOSSARY. 33

CHAW. To chew. It may be merely the Cotswold pronunciation of chew: Chaw was

formerly written for jaw.

"I will put hookes in thy chawes." Ezekiel xxix. 4, and again xxxviii.

4, Breeches Bible.

CHAWK To gape. Spoken of apples chipped in the rind, viz., the chawn-pippin;

also the earth opening in dry weather: x avV0) > Greek Probably of Indo-

Germanic origin, and a word in use both by the Greeks and the Teutonic tribes.

u thou all-bearing earth, Which men do gape for, till thou cramm'st their

mouths, And choak'st their throats with dust; chaune thy breast, And let me

sink into thee."

Ant. and Mell. Anc. Dr. II. 144. See Nares's Glossary.

CHILVER A ewe-lamb: Cilfer, Saxon.

CHISSOM. To bud forth. Especially applied to the first

shoots in newly cut coppice. CHOCK-FULL. Full to choking.

CHUKK. The udder of a cow: Cirt, Saxon, benignitas, largitas, metaphorically

used (?)

CLAMMY. Adhesive, sticky: This may be a metaphor drawn from the Shropshire

word " Clem," to starve; because the skin then adheres closely to

the attenuated frame.

CLAVEY. Mantle-piece; chimney-piece: Cladde, Welsh.

CLAY- E AG. A composite stone, found in clay-pits.

CLEATS. A small wedge, commonly of wood.

CLEAVE. To cling to; also to burst hard bodies asunder by wedges: Clifian,

Saxon.

"The clods cleave fast together. "Job, xxxviii. 38. " The men

of Judah clave unto their king." II. Samuel, xx. 2. " The thin

camelion, fed with air, receives The colour of the thing to which he

cleaves." Dry den. * * Like our strange garments, cleave not to their

mould, But with the aid of use." Shakespeare.

D

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2898) (delwedd 2898)

|

34 GLOSSARY.

" The priests with holy hands were seen to tine The cloven wood."

Dry den.

OLITES. A plant, cleavers; Galium Aparine: Clate Saxon.

"A clote-lefe he had laid under his hode."

Chaucer. Chanon's Yeman's Prologue.

CLOUT. A heavy blow; Clud, Saxon; metaphorically derived from the clouded and

swelled appearance caused by a heavy blow.

CLYP. To embrace: Clippan, Saxon.

"That Neptune's arms, who clippeth thee about, Would bear thee from the

knowledge of thyself."

Shakespeare, King John, act v. sc. "2.

COLLY. Subst., Dirt, also the blackbird; Adject., black, dark; Verb, to

defile: Coal (?) In Spanish Hollin is soot.

" Brief as the lightning in the collied night." Shakespeare,

Midsum. Night's Dream, act i. sc. 1.

" Nor hast thou collied thy face enough, Stinkard!" Ben Jonson, Poetaster,

activ. sc. 5.

COLT. A landslip.

COMB. A valley with only one inlet: Comb, Saxon.

CONCEIT. To think, to believe; Subst, A strong mental impression: Concipio,

Latin.

" The strong, by conceiting themselves weak," &c. Dr. South. "

One of two bad ways you must conceit me, Either a coward or a

flatterer." Shakespeare. "A blunt country gentleman, who

understanding but little of the world, conceited the earth to be fastened to

the North and South poles by great and massy cakes of ice."

Hagiastrologia, J. Butler, b.d. 1680, p. 45.

" The same year Sir Thomas Egerton, the Lord Chancellor, died of conceit,

fearing to be displaced." Diary of Walter Yonge, Esq., 1619, p. 33.

COO-TEE. The wood pigeon's note.

COUNT. To consider; to suppose: Compter, French.

" Count not thy hand-maid for a daughter of Belial. " I. Samuel, i.

16.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2899) (delwedd 2899)

|

GLOSSARY. 35

" Nor shall I count it heinous to enjoy The public marks of honours and

rewards." Milton.

COUKT-HOUSE. The manor-place, so called because the lord held his manor-court

there.

CEANK. A dead branch of a tree: Krank, Dutch, sick, weakly.

CEAZY. A plant the Ranunculus Acris.

CEINCH. A morsel: Crunch, Sanscrit, to lessen, to diminish.

CEO WISHED. A pollard is said by the woodwards to be crowned, when the rind

has healed over the wound.

CUCKOLD. The seed-pod of the Burdock; as being shaped like the human head,

and covered on all sides by little horns (?)

CULL. A small fish, the miller's thumb: Callan, Sanscrit, a small fish.

D.

DAAK. To dig up weeds: Daque, French.

D ADDLES. Said, playfully, of the hands: Tatze, German.

DADDOCKY. Said of decayed timber: Quasi, dead oak (?)

DAP. To sink and rebound: Doppetan, Saxon.

DAP-CHICK. A bird, the little grebe, one of the divers.

DAY-WOMAN. Dairy-maid: Deggia, Icelandic, to give suck.

"For this damsel, I must keep her at the park; she is allowed for the day

-woman." Shakespeare, Love's Labour Lost, acti. sc. 2.

DEADLY. A word meaning intenseness in a bad sense,

as "deadly lame," "deadly sore," "deadly

stupid," &c. DENT. An indentation: Dens, Latin, a tooth. DESIGHT. A

blemish.

d 2-

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2900) (delwedd 2900)

|

36 GLOSSARY.

DESPEKD. Beyond measure, extremely: used in an evil sense: Desperate.

DISANNUL. To annul; a reduplication of the sense: Nullus, Latin.

" The Lord of Hosts hath purposed, and who shall disannul it?" Isaiah,

xiv. 27.

" Wilt thou also disannul my judgment!" Job, xl. 8. "For there

is verily a disannulling of the commandment." Hebrews, vii. 18, and in

other places in the Bible.

" Pope Pius the Fourth reflecting on the capricious and high answer his

mad predecessor had made to her address, sent one Parpalia to her, in the

second year of her reign, to invite her to join herself to that See, and he

would disannul the sentence against her mother's marriage." Bp. Burnet,

Hist, of the Reformation, Part II. bk. hi. p. 417, fol. ed. 1681. 11 Then I

might easily disannul the marriage. Scapin. Disannul the marriage!"

Otway, Cheats of Scapin, act i. sc. 1.

DISMAL. Any evil in excess " He do cough dismal!" DOFF. To take off

clothing: Do-off (?)

" He that unbuckles this, till we do please To doff't for our repose,

shall bear a storm."

Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra, act iv. sc. 4.

DOLLOP. A lump; a mass of anything.

" Of barley, the finest and greenest ye find, Leave standing in dallops,

till time ye do bind."

Tusser's Husbandry, August 17.

DON. To clothe; to put on: Do-on?

" Menas, I did not think This am'rous surfeitor would have donn'd his

helm."

Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleop. act ii. sc. 1. " Then up he rose and

donned his clothes." Hamlet, act iv. sc. 5. "Some donned a cuirass,

some a corselet bright." Fairfax, Tasso, i. 72.

DOKMOUSE. Applied to the bat, because he sleeps in winter: dormio, Latin.

DOUT. To extinguish a light; to put out a candle: Do out (?)

" First, in the intellect it douts the light." Sylvester, Tobacco

battered,^ 106.

DOWLE. Down on a feather; the first appearance of hair: Probably, Down,

corruptly used.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2901) (delwedd 2901)

|

GLOSSARY. 37

" May as well Wound the loud winds, or with be-mockt-at stabs Kill the

still-closing waters, as diminish One dowle that's in my plume. "

Shakespeare, Tempest, act iii. sc. 3.

DRAVE, the same word as Thrave. A truss of straw; and by metaphor, a flock of

animals, a crowd: Thraf, Saxon.

" They come in thraves to frolic with him." Ben Jonson.

DRINK. Used as a term for beer; and limited to that beverage.

" And sometimes make the drink to bear no barm." Shakespeare, Midsummer

Night's Dream, act iii. sc. 3.

DROXY. Spoken of decayed wood: Drogenlic, Saxon. DRUJSTGE. To embarrass, or

perplex by numbers:

Throng (?) mispronounced. DTHONG. Painful pulsation: Stang (?) Icelandic,

same

sense.

DUDDLE. To stun with noise: Dyderian, Saxon.

DUDGEON. Ill-temper; also the dagger, as the result thereof.

" When civil dudgeon first grew high, And men fell out, they knew not

why." Hudibras.

DULKIN, DELKIN. A small, but dark descent; a ravine; Dell, or dale, with kin

as a diminutive.

DUMMLE. Dull, slow, stupid: Dom, Dutch.

DUNCH, DUNNY. Deaf; also imperfection in any of the faculties.

" What with the zmoke, and what with the criez, I was a'most blind, and

dunch in my eyez."

MS. Ashmole, 36, f. 112. See Halliwell's Diet.

DUP. To exalt; do up (?) Possibly a metaphor from the portcullis.

DURGAN. A name found for a stocky, undersized horse, in all large teams:

Dwerg, Saxon, a dwarf.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2902) (delwedd 2902)

|

38 GLOSSARY.

DWA-AL. To ramble in mind: Dwa-elen, Teuton. DWAM. To faint away.

DYNT. The impression made by a heavy blow: Dynt Saxon.

E.

EIEY. Spoken of a tall, clean-grown timber sapling Possibly, as tall enough

to be chosen by the hawk fo her eiry (?)

ELVER A small eel: El, Saxon.

ENTENNY. The main doorway of a house: Always so mispronounced.

ETTLES. Nettles: A common mispronunciation.

EYAS. A young hawk: A falconer's term, not yet lost, derived from Eye; (as

next below.) See " Hamlet," act ii. sc. 2.

EYE. A brood of pheasants: Ey, an egg, German.

" Sometimes an ey or t way. "Chaucer, The Nonnes Priest's Tale, 1.

38.

"Unslacked lime, chalk, and gliere of an ey." Id. The Chanones Yeman's

Tale, 1. 252.

" The eyren that the hue laid. "Deposition of King Richard II.

FAGGOT. A word applied in derogation to an old woman, as deserving a faggot

for witchcraft or heresy.

FALL of the year. Autumn: Falewe, Saxon; to grow yellow: the colour fallow.

FEND. To forbid; to defend: Defendre, French.

FILLS see also TILLS, THILLS, TILLEK-HOKSE. The

shafts of a cart: Thill, Saxon.

"If you draw backwards we'll put you in the fills. "Shakespeare, Troil.

and Ores., act iii. sc. 2.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2903) (delwedd 2903)

|

GLOSSARY. 39

FILTHY, VILTRY. Filth of any kind; weeds in cultivated land.

FLAKES, FLE-AK. A wattled hurdle.

FLAT. A common term for a low, concave surface in a field.

FLICK. Verb. To tear off the skin or felt by the smack of a whip, or the

hasty snap of a greyhound when he fails to secure the hare; Subst., the fat

between the bowels of a slaughtered animaL

"I'll lend un a vlick." Fielding's History of a Foundling, Squire Western

passim.

FLOWSE, FLOWSING. Flowing, flaunting: Fliessen, German.

" They flirt, they yerk, they backward fluce, they fling, As if the

devil in their heels had been." Drayton.

-FLUMP. Applied to a heavy fall " he came down with

a flump:" Plump (?) FLUSH, or FLESHY. Spoken of young birds fledged. FORE-RIGHT.

Opposite to: Foran, Saxon. FOR- WHY. Because; on account of: For-hwe, Saxon.

"For why? The Lord our God is good." 100th Psalm, Old Version. "For

why? He remembered His holy promise." Psalm cv. 42, Prayer-book Version.

FRITH. Young white thorn, used for sets in hedges: Ffrith, wood, Welsh.

" To lead the goodly routs about the rural lawns, As over holt and

heath, as thorough frith and fell. "

Drayton. " He hath both hallys and bowrys, Frithes, fayr forests, and

flowrys."

Romance of Emare*. " When they sing loud in frith or in forest."

Chaucer.

FRORE, FROR. Frozen: Frieren, German.

" The parching air Barns frore, and cold performs the part of

fire." Milton. " And some from far-off regions frore." Bishop

Mant, British Months, January, 708.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2904) (delwedd 2904)

|

40 GLOSSARY.

FROM-WARD, FROM-MARD. Opposite to Toward.

ERUM, FROOM, FRIM, FREM. Full, abundant, flourishing: From, Saxon.

"Through the frira pastures at his leisures." Drayton.

G.

GAITLE. To wander idly: Ge-gada, Saxon. GAITLING, GADLING. An idler; a

loiterer.

" When God was on earth and wandered wide, What was the reason why he

would not ride? Because he would have no groom to go by his side, Nor

discontented gadling to chatter and chide. "

Old Song, Wright's House of Hanover.

GALLOW. To alarm; to frighten: Agselan, Saxon.

" The wrathful skies Gallow the weary wanderers of the night."

Shakespeare, King Lear, act iii. sc. 2.

GALLOWED, or GALLARD. Frightened.

GALORE. An exclamation signifying abundance: Gulori, Gaelic.

Frequent in ballads. See Sibbald's, Bitson's, and Percy's Collections.

GAMUT. Sport: Gamen, Saxon; Gaman, Icelandic.

"And that never on Eldridge come To sport, gamon, or playe."

Percy's Reliques, Sir Cauline. 112. "All wite ye good men, hu the gamon

goth." Political Song, Wright, p. 331, 1. 180.

"There was a gamon in Engelond that dured zer and other, Erliche upon

the Munday uch man bishrewed others; So long lasted that gamon among lered

and lewed, That n'old they never stinten, or al the world were

bishrewed."

p. 340, 1. 367.

GAULY, GAUL, GALL. Sour marsh-land, metaphor taken from " gall," a

wound; which sense is also in common use: Gealla, Saxon.

GAYN", and its contradictory, UN-GAYN. Happily advantageous; lucky.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2905) (delwedd 2905)

|

GLOSSARY. 41

GEAR Harness; apparel: Gearwa, Saxon.

" The frauds he learned in his frantic years, Made him uneasy in his

lawful gears." Dryden.

GICK, GE-AK, KECK, KEXIES. Dry stalks, more especially of the tall,

umbelliferous plants; Geac, Saxon.

" And nothing teems But hateful docks, rough thistles, kexies,

burs."

Shakespeare, Henry V., act v. sc. 2. " If I had never seen, or never

tasted The goodness of this kix, I had been a made man."

Beaumont and Fletcher, Coxcomb, act i. sc. 2. "With wyspes, and kexies,

and rysches ther light To fetch horn their husbandes, that wer them trouth-

plight."

Bitson, Antient Songs, Tournament of Tottenham, p. 93.

GIMMALS. Hinges: Gemelli, twins, Latin.

GLOWR. To stare moodily, or with an angry aspect; Gluren, Teuton.

GLOUT. To look surly or sulky: Gloa, Suio-Gothic.

" Glouting with sullen spight, the fury shook Her clotted locks."

Garth.

GLUM, GLUMP. Gloomy; displeased: Glum, Teuton.

" Whiche whilom will on folke* smile, And glombe on hem an othir while.

"

Chaucer, Bomaunt of the Bose, 1. 4356.

GODE. Past tense of To go, often softened into yode.

" As I yod on a Monday Bytweene Wiltinden and Walle."

Bitson, Ballad on the Scottish War, 1. 1. " In other pace than forth he

yode Beturned Lord Marmion."

Sir Walter Scott, Marmion, canto iii. xxxi.

GRIP. A drain: Grsep, Saxon.

GRIT. Sandy, stony land: Gritta, Saxon.

" Pierce the obstructive grit and restive mail." Phillips.

GROANING. Parturition: metaphorically used.

" You may as safely tell a story over a groaning- cheese, as to him."

Farquhar, Love and a Bottle, act ii.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2906) (delwedd 2906)

|

42 GLOSSARY.

GEOUNDS. Commonly used for fields, and those usually grass-lands.

GROUTS, GEITS. Oatmeal; also dregs: Grut, Saxon.

" King Hardicnute, 'midst Danes and Saxons stout, Caroused on nut-brown

ale, and dined on grout." King. "Sweet boney some condense, some

purge the grout." Dryden.

GULCH. A fat glutton: Gulo, Latin.

"You'll see us then, you will, gulch." Ben Jonson, Poetaster, act

iii. sc. 4.

"Thou muddy gulch, darest look me in the face?" Brewer.

GULLY. A deep, narrow ravine, usually with a rill therein: Gill, North

country dialect.

GUMPTION. Spirit; sense; quick observation: Gaum, Icelandic.

" Within two yer therafter some to Morgan come, And, for he of the elder

soster was, bed himnyme gome."

Robert of Gloucester, p. 38, Hearne's Ed. "An eh, troth, Meary, I's as

gaumless as a goose." Tim Bobbin, p. 52.

GUEGINS. The coarser meal of wheat: quasi Purgings (?)

HACKLE. A gamekeeper's word; To interlace the hind-legs of game for

convenience of carriage, by houghing the one and slitting the film of the

other limb.

HAINE. To shut up a meadow for hay: Haye, a hedge, French.

HALE, pronounced " Haul." To draw with violence, or with a team:

Haa-len, Dutch.

" Lest he hale thee to the judge." St. Luke, xii. 58.

HAMES, plural HAMES-ES. The wooden supports to a horse-collar in teams; made

of metal in coach-harness.

HANDY. Near; convenient; when applied to an individual, clever: Gehend,

Saxon.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2907) (delwedd 2907)

|

LOSSARY. 43

HANK. A skein of any kind of thread.

HARBOUR. To abide; to frequent: Herebeorgan, Saxon.

" This night let's harbour here in York." Shakespeare. '* Let not

your gentle breast Harbour one thought of oiitrage from the king." Rowe.

HARSLET. The main entrails of a hog: Hasla, Icelandic a bundle.

"There was not a hog killed in the three parishes, whereof he had no^ part

of the harslet, or puddings." Ozell's Rabelais, iii. 41. See Nares'fc Glossary.

HATCH. A door which only half fills the doorway. HAULM. Dead stalks: Healm,

Saxon,

" In champion countries a pleasure they take

To mow up their haum, for to brew or to bake." " The haum is the

straw of the wheat or the rie."

Tusser's Husbandry, January 14, 15.

HAUNCHED. To be gored by the horns of cattle: from Haunch, where the wound

would usually be inflicted.

HAY-SUCK. Hedge-sparrow: Hege-sugge, Saxon.

"Thou murdrir of the heisugge on the braunche That brought thee

forth."

Chaucer, Assemblie of Fowles, 1. 612.

HAYWARD. An officer appointed at the court leet, to see that cattle do not

break the hedges of enclosed lands, and to impound them when trespassing.

Hegge, Saxon.

" The Hayward heteth us harm." Political Songs, temp. Edward I., p.

149. Wright.

HAZEK To chide; to check a dog by the voice: Haesa, Saxon, mandatum.

" Haze, perterrifacio." Ainsworth's Dictionary.

HEATHER. The top-binding of a hedge: Heder, Saxon.

" In lopping and felling save edder and stake, Thine hedges, as needeth,

to mend, or to make."

Tusser's Husbandry, January 13.

HEEL of the hand. The part above the wrist, opposite

the thumb. HEFT. Subst, Weight, burden; Verb, To weigh: Hceftan,

Saxon.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 2908) (delwedd 2908)

|

44 GLOSSARY.

HELE. To cover: Helan, Saxon.

" Parde\ we women connen nothing hele, Witness on Midas."

Chaucer, Wife of Bathes Tale, 1. 94.

HELIAR A thatcher.

HIC-WALL The green woodpecker: Name derived from his cry.

11 The crow is digging at his breast amain, The sharp-nebbed hecco stabbing

at his brain." Drayton. "And this same herb your hickways, alias

woodpeckers, use."- Ozell's Kabelais, iv. 62.

HIGHST. To uplift; to hoist.

HILLAED, HILLWAED. Towards the hill or high country.

HILT, see Yelt.

HINGE. The liver, lungs, and heart of a sheep, hanging to the head by the

windpipe: Hangan, Saxon.

HIVE. To cherish; to cover as a hen her chickens: Hife, Saxon.

" And sesith on her sete, with her softe plumes, And hoveth the