|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9737) (tudalen 002)

|

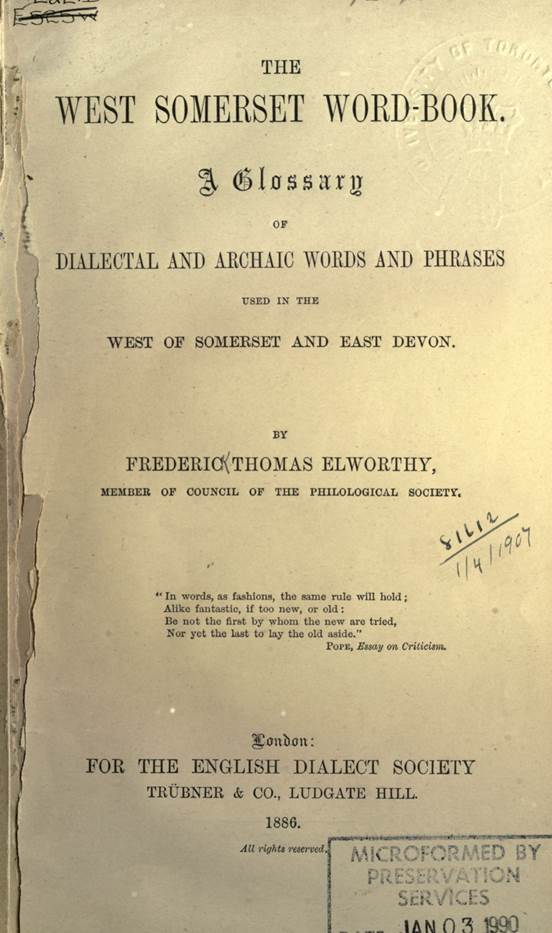

THE

WEST SOMERSET WORD-BOOK.

OF

DIALECTAL AND ARCHAIC WORDS AND PHRASES

USED IN THE

WEST OF SOMERSET AND EAST DEVON.

BY

FREDERICK THOMAS ELWORTHY, MEMBER OF COUNCIL OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIETY.

"In words, as fashions, the same rule will hold; Alike fantastic, if too new, or old: Be not the first by whom the new are

tried, Nor yet the last to lay the old

aside."

POPE, Essay on

Criticism.

LONDON

FOR THE ENGLISH DIALECT SOCIETY

TRÜBNER & CO.,

LUDGATE HILL.

1886.

All rights reserved.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9738) (tudalen 003)

|

K. Clay and Sons,

London and Bungay.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9739) (tudalen 004)

|

CONTENTS.

PAGE

PKKFACE v

INTRODUCTION ........ xv

KEY TO GLOSSIC AND EXPLANATIONS xlvii

VOCABULARY ......*.. i

LIST OF LITERARY WORDS NOT PRONOUNCED AS IN STANDARD

ENGLISH . . . . . . . . -855

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9740) (tudalen 005)

|

PREFACE.

ALTHOUGH the work of observing and recording peculiarities of native speakers may fairly be considered as

original research, yet the labours of

those who have before done the same thing in other districts are of immense value to an

observer, and therefore it is fitting

that acknowledgment of the obligation should be placed in the very fore-front of these pages.

The various workers of the Dialect Society are of the greatest use to each other, by reason of their

bringing the folk-speech of different

localities into a sort of focus; and thus they suggest to an observer what he should look for in his

own. The greatest difficulty to be

dealt with is not that of becoming familiar with local speech, but of deciding what is

provincial or dialectal, and what is

standard English for nowadays so many novelists and other writers employ words and forms of

expression they know more or less as

being used in the place they are dealing with. These words, however, are not literary

English, nor are they slang; yet from

frequent use they have become current, although they have not yet found their way into

dictionaries, nor will they until Dr.

Murray's gigantic task is finally completed. These writers are, unconsciously, but steadily, building up a

sort of conventional literary dialect,

containing a little of several, but not confined to any one in particular. Whether this will

tend to the improvement of literature,

or the true knowledge of the English language, is beyond the scope of this Word- Book.

For any particular detail in the following pages I am unconscious of being indebted to any of the Glossarists

who have preceded me, but to all I am

obliged for many suggestions.

Long experience has now convinced me of that which I put forward in my first paper on the subject,

in 1875, that our

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9741) (tudalen 006)

|

v j

PREFACE.

hereditary pronunciation will survive, together with our grammatical pIculiaritLs, long after board schools and

newspapers have brought English as a

written language to one dead level.

Holding this view, which Dr. Henry Sweet says (on Laws of Sound I Change, FhU. Society,^. |, 1886) is

now general y admitted by

philologists," I have given much attention and space to pronunciation, and to grammatical and

syntactic construction, which I trust

may not be found useless to future students.

A comparison of our present dialectal pronunciation of many literary words with their forms in Early

and Middle English, will prove how

very slow phonetic changes have been m the past, at least in the spoken language of the people.

The same holds good, and will be found

to be fully illustrated in these pages, with respec to many forms of grammar and syntax which

have long become obsolete in literature.

Both these subjects have been dealt with

at some length in former papers published by this Society, and shall therefore only endeavour now to

notice some facts previously

unobserved, or not adequately recorded.

Inasmuch as a great deal of the peculiarity of a dialect is altogether lost if attempted in

conventional literary spelling, or

even in modifications of it, I have continued to use Mr. Ellis's Glossic, which though at first sight

uncouth in appearance to those

accustomed only to conventional spelling, yet is extremely easy

to read after a very little practice.

I have not followed all the extreme

refinements of the system; but to have a definite and distinct method at all is, it seems to me,

of far more importance than either the

use or the merits of this or that system of notation. A full and elaborate key will be found on

p. 24 of my Dialect of West Somerset,

1875, and a concise one, quite sufficient for the understanding of all here written, is on p.

2 of the Grammar of l\\-st Somerset,

1877. This latter is reprinted at the end of the Introduction (p. xlvii).

It seems almost needless to offer anything by way of defence against the criticisms which are certain to

be applied to phonetic spelling; but

unless some definite plan is to be followed, how is a stranger, a foreigner for instance, to be

made aware of the difference in sound

of o in come, gone, bone; of a in tardy, mustard; or of / in mind and wind? Could such a

sentence as that which illustrates

LIMBLESS be contrived in conventional spelling? I shall indeed be satisfied if critics confine

their disapproval of this book to the

Glossic.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9742) (tudalen 007)

|

PREFACE.

Vli

I have noticed among the works issued by this Society many attempts to convey the sound of words by

ordinary values of letters, for

instance, I find “Footing pronounced Fuutirf," but no clue is given as to the value of the two us, and

not knowing the dialect I am no wiser.

Hallivvell has “Allous; all of us Somerset," but what stranger to the county, or foreigner, would guess

that this should be pronounced au'l oa

uus?

I have in the following pages endeavoured to give clear definitions of words,

and where they related to anything of a technical character I have tried to describe the

object, so that those who come after

us may be able to know precisely what the article now is. Who can now say with any certainty what

size, shape, or capacity, was a biker

of the i5th century? The beaker of modem

novelists is something very different, even if it be not a

fabulous article. What will people

understand of a Yorkshire “Sfoup, a

wooden drinking vessel "? Halliwell describes “Clevvy, a

species of draft iron for a

plough." What species? He gives “Ledger,

horizontal bar of a scaffold." Which? Forby gives "Spud,

an instrument, a sort of hoe."

What sort? Instances of similar

indefinite definitions might be multiplied to any extent. I trust I have not run into the other extreme of

describing at length that with which

everybody is familiar. Skillett and crock are common names of household utensils, but not many

town-bred people could distinguish

them in an ironmonger's shop.

In deciding whether a word or phrase is literary or not, I have followed no exact rule. Generally words, or

meanings of literary words, if given

in Webster, have not been inserted; but for some words, though literary, there have appeared

reasons, such as pronunciation, or peculiarity of use, why they should

appear. In such cases they are not,

however, allowed much space. I have acted

on the best advice I could obtain to insert doubtful words shortly, rather than omit them.

Ordinary colloquialisms, such as all to smash, cross-patch, crow's feet, crusty, a setting-down, stone-blind,

spick and span, transmogrify, are not

here noted, though I observe that many glossaries contain such words, but space had to be regarded,

or this book would have been unwieldy.

I have in no case considered whether a word was widely known, or peculiar to this district;

so that if in my opinion it was a

dialect word, I have inserted it, though common from John o' Groats to the Land's End. ' On this

point I fully expect

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9743) (tudalen 008)

|

vJIJ

PREFACE.

to hear exception taken; but if there is any value at all in preserving

current speech, by no means the least is to be able to define how far any particular word or

phrase is known, and in what sense it

is so known. Therefore I offer no excuse to the r from Northumberland who finds here a word

familiar to him, unless it is found in

the dictionaries in the sense in which

I have given it; in that case I acknowledge my faults and

apologize accordingly.

Certain well-known names of common articles have been inserted as a sort of legacy to the future these are

now obsolescent, and probably in a few

years will be quite forgotten e. g. pattens,

gambaders, &c.

Further, I have not taken any word at second-hand except in a few cases, where I have specially given my

informant's initials; but every word

noted has been heard spoken by myself (except as above), and must be accepted, or otherwise, on my

own testimony alone. And here I would

remark that the one point I have kept steadily in view has been truth. So far as I am

conscious I have neither under nor

over'stated, unless it may be in the use of the word (always) which will be found after many of the words

to indicate that among dialect

speakers the expression is that which is the usual and ordinary one, and that any variation

from it would be quite exceptional.

In Halliwell I find many errors. Very numerous words which he gives as "Somerset" or

"West," are either obsolete or quite unknown, while many others described as

peculiar to other districts, are

familiar in this, and probably have been so for ages Cheatery = fraud, “North," is one of

our commonest words.

Again, many words undoubtedly peculiar to us are wrongly defined for

instance, "Clavy-tack. A Key. Exmoor" Except the coincidence of clav there is nothing even

to suggest the idea of key. The

article, a mantel-piece or shelf, is perfectly common.

In the following pages I repeat that I have taken nothing from Halliwell, nor from any other Glossary, but

I have used them merely as reminders

of words which I had omitted; and for this purpose I have found Pulman's Rustic Sketches by far

the most valuable. I have quoted

freely from his verses, and so far as dialect goes, he is by a long way the most accurate, and less

given to eke out his versification

with literaryisms. On this point, however, he does but II other writers of the same class, not

excepting Barnes, have done-humour and

quaintness first, dialect and correct construction

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9744) (tudalen 009)

|

PREFACE.

IX

of the spoken language second. Moreover, Pulman's district is closely allied to this, as also is that of

Nathan Hogg and Peter Pindar. It will

be understood then that any word given as Somerset by Hallivvell, if not mentioned herein, is

unknown in West Somerset so far as I

can ascertain. A peculiarity of all Western Dialect poets except Pulman, who refers to the point in

his preface, but yet is guilty in his

verses, is that all common English words in /are spelt with v, and all words in s are spelt with

z. No doubt it is very funny; both

Shakspere and Ben Jonson adopted that method to distinguish a clown; a method which has

become conventional, and has lasted

down through Fielding to our own day in Punch. But notwithstanding such authorities it is

incorrect. Ben Jonson never heard

anybody say varrier (Tale of a Tub} who was speaking his own genuine tongue. In many cases,

however, there is uncertainty of pronunciation, and apparent exception to the

rule that words in f or s, if

Teutonic, are sounded with initial v or z 9 while French or other imported words with the

same initials, keep them sharp and

precise (see VETHERVOW). For example, file, for bills, is always fuyul (O. Fr. file), while file,

a rasp, both v. and sb., is always

vuyul, (Dutch, vijl). Indeed it may be taken as a rule that where literary words in /or s have their

counterparts in Dutch, our Western

English dialectal pronunciation of the initial is the same; compare finger, first, fist, fleece,

follow, foot, forth, forward, freeze,

see, seed, seek, self, send, seven, sieve, silver, sinew, sing,

sister, six, &c. In exceptional

cases where the rule does not hold good, it will usually be found that there has been a

confusion of meaning owing to

similarity of sound. For instance, summer, a season, and summer, a beam (Fr. sommier) are both alike

sounded zuum'ur, whereas but for

confusion in consequence of similarity of sound, the latter would probably have been

suum'ur. Sea again is exceptional, and is always sai m with s quite sharp,

while see and say are always according

to rule zee and zai.

How common these confusions of meaning and sound are, and to what results they lead must be within

the experience of most observers. At

this moment upon the wall of the boot and knife house at Foxdown is a grafitto, very well

written in Board School hand,

immediately over a fragment of looking-glass-Things seen is Intempural Things not seen is Inturnel .

Sunday, Aug. 23, 1885.

Another of my servants always says of a kind of artificial manure

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9745) (tudalen 010)

|

x

PREFACE.

"that there consecrated manure's double so good's the tother." He has heard it called concentrated.

Imperfect imitation of foreign pronunciation of imported words leads to variety of sound in different

districts, and eventually to apparent

change, when the form of a particular district or a literary appreciation becomes the standard. For

example, gillyflower and manger, about

which there can be no controversy, are now literary names; but how very unlike they are in

sound to their prototypes girojlcc and

man^coire, and how much nearer to what are probably the original O. F. sounds of these words

are our rustic julau'fur and mau-njur.

All these points will be found dealt with in the text.

I have ventured to include many technical words, some of which are peculiar to the district, and others

are common to the trades to which they

apply, but in most cases I think there are some points of divergence from ordinary trade or

hunting terms, sufficient to make them

worth recording here. In some cases it will be found that common terms have in this district

quite a different signification to that current elsewhere e.g. ALE and BEER,

while in others we have our own

distinct names for common things e. g. LINHAY, SPRANKER, &c.

Upon the slippery path of etymology I have been careful not to tread, and whenever any remark upon that

point has been made, it has always

been with much diffidence and merely by way of suggestion, or in a few cases where

received explanations are

unsatisfactory or improbable. Of course I shall be charged with omitting the most interesting part of the

whole matter, but for many reasons I

have confined myself to bare identification with Old or Middle English, or with some foreign

language, where both sense and sound

render such identification obvious. The book

is already over bulky, and etymological speculations would have distended it, and possibly destroyed what

little value it may now possess.

Moreover, an observer and recorder of facts has no business with theories, and be he never so

circumspect in his enunciation, he

cannot escape the suspicion that in his desire to prove his propositions, his facts have

been at least marshalled, and his work

will only be valued accordingly. Even if I had felt tempted at any time to branch off into that

line, I was long ago cured of the

symptom by a gentleman who has established a large for learning of all kinds. Meeting him one

day, he was as usual anxious to

instruct the ignorant, and he inquired if I knew

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9746) (tudalen 011)

|

PREFACE.

XI

the origin of the word sheriff. I replied that I had always thought it was a shortened form of shire-reeve.

“Nothing of the sort," was the

confident reply, “it is an Arabic word: shereef is the head man." About the same time another

gentleman asked if I knew our word

soce, and what it came from. Previous experience led me to reply cautiously, but I was as

confidently informed as by the first

gentleman, that the speaker's uncle was a great scholar, and that "he always said soce came from the

Greek Zwoe-" A well-known writer

some years ago pointed out to a friend of mine that Yarrow was a common name for river;

“doubtless," he said “from the

Anglo-Saxon earcwe, an arrow, because they run straight and fast. Thus," he continued, “we have the

Yarrow in Scotland, the Yarra in

Africa, and the Yarra-yarra in Australia." In this way it is clear that there must be a close connection

between the Goodwin Sands and

Tenterden Steeple, for of course the termination le is a mere surplusage, and to steep means to

place under water, while to tenter

obviously suggests the idea of drying again, and thus the analogy is complete, if not obvious.

Although these were examples of identification rather than scientific etymology, I trust I learnt the

lesson sufficiently to avoid at least

anything like confident assertion. Indeed, I have arrived at the conviction that speculation as to

the meanings and origins of words, is

a luxury not to be -even aspired to by any but those whose reputation is established, like the

gentleman above referred to, and

therefore, though advised by those whose opinion I deeply respect and value, to “give a good guess as

to the origin of a word whenever you

can," yet I have not done so, because expecting to be done by as I do, I accept with less

reserve the statements of those who

admit in these omniscient days, that there may be something in, on, or under the earth, which

they do not know all about.

How old a habit dabbling in etymology has been, and how deep the pit-falls it leads people into, are

shown in the following

Britones wer' long j clepud Cadwallesme,

After Cadwall >* was hur' kyng; Bot

Saxsous clepud hem 3ey}then Walsheme,

By cause of sherte spekyng.

A. D. 1420. Chronicon Vilodunense^ st. 24.

The Word Lists printed at the end do not profess to be exhaustive of the words in use by the

people of the district, nor even to

give more than a portion of the common ones, inasmuch

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9747) (tudalen 012)

|

x jj

PREFACE.

as different degrees of education involve the use of a larger or smaller vocabulary. They consist entirely

of literary words, which are not

pronounced in the usually received manner, and therefore it may be taken that any word not in the

list would, if used at all, be sounded

approximately as in standard English.

Of myself, it is enough to say that I have lived for more than fifty years in the district, and have had

the best possible opportunities of hearing and of practising my native

tongue, while for over twenty years I

have been a diligent observer and careful

noter of its peculiarities; the result of this observation is contained in the papers already published, and in the

following pages. During the past ten

or twelve years these special observations

have occupied most of my leisure time, while for the past

eighteen months preparing and

correcting for the press has left no time

at all for any other occupation; whether or not the end accomplished

is worth the very great labour bestowed must be left for others to decide. The work has, however,

been a labour of love, and has brought

me into closer contact with my humbler neighbours than any other pursuit

could have done; so that I have become

familiar not only with their forms of speech but with their mode of thought. No doubt in the plan

adopted of giving nearly every word

its setting in its own proper matrix, a great similarity and repetition of phrase will be apparent,

while anything like humour will have

to be hunted for. To this I say that the people we are studying are not specially humorous,

but rather stolid, and that to

represent their speech accurately, including dullness and repetition, is the end I have aimed at.

There is much grim, rustic humour in

the people, and it is hoped that at least some traces of it may be found herein. Of

coarseness also there is and must be a

good deal; and while I have felt that I could not but record it, I trust nothing offensive has

been retained. Advisers have urged me

to suppress nothing, and I have been told that the strongholds of a language are in its

obscenities. I have in this taken

their advice, I have not suppressed any, but yet trie most fastidious will find nothing in this book

approaching to obscenity, nor indeed

greater coarseness of expression than is contained in our expurgated Shaksperes. The reason is

that there is nothing to suppress; the

people are simple, and although there is a superabundance of rough, coarse

language, yet foul-mouthed obscenity

is a growth of cities, and I declare I have never heard it, so it cannot be recorded by me.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9748) (tudalen 013)

|

PREFACE.

Xlll

It must be understood that in a book of this kind only generalities of

pronunciation, or rather types, are possible, for in the first place no two individuals sound all words

quite alike, while from village to

village, in some slight peculiarity or other, there is a marked difference to an accustomed ear. A

lengthening of a vowel, a slight

stress in some common word, are quite enough to mark off people from others living not far away; but to

attempt to write these fine shades of

difference would be far beyond the scope of the most elaborate notation, even if the person who

observed and recognized the

peculiarity were able himself to define or imitate it.

I have been frequently struck with the inability of otherwise intelligent people, who would both speak

and write conventional English

correctly, to appreciate dialect; that is of course where they have been always accustomed to it. They

seem to be strangely unconscious that

hosts of words, phrases, and pronunciations which they hear daily are anything out of the

common, or different to what they

would use themselves in speaking to their own class.

Long practice in watchful observation has enabled me to detect variations which to ears equally familiar

with the dialect of the district are

often quite imperceptible. Many curious proofs of this have occurred during the past few years. I

wanted with a friend to look round the

Nothe fort at Weymouth, and on speaking to -the sentry, the man replied in three words,

“that's the door." Being in

Dorsetshire, I of course was struck by the man's pronunciation of door, and said at once to him, "I

see you are a Somerset man."

"Yes." "I think you must know Huish Champflower, do

you not? “" Well, yes, I ought to

I was born and bred to Clatworthy." Huish and Clatworthy are adjoining

parishes, their churches barely a mile

apart. This was a trained artilleryman,

with not the vestige of a clown left in him. On two occasions in London shops: I was a passive listener at

Brandon's while a bonnet was being

discussed, and when making the payment ventured to remark to the young lady,

“You must have been a long time in London."

"Oh, yes, ten years; but why do you ask?" “Only for information," said I; “and

did you come straight from Teignmouth?

“With much surprise at my supposing she came

from Devonshire, she said at length that she was a native of Newton Abbott. I could not pretend to define the

precise quality of her two, but it was

only in that one word that I recognized her locality. Another young lady under like circumstances

I fixed correctly at Exeter. Quite

recently a Spiers and Pond young lady at a railway

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9749) (tudalen 014)

|

PREFACE.

bar said she came from South Molton, when I asked if she did not come from Barnstaple. It is not my

practice to go about questioning people in this way; indeed, I do not

remember having done so more than a

dozen times in my life, those referred to

included, but certain limited districts are very marked, though I could not attempt to define how.

A real Taunton man I should know in Timbuctoo, and a Bristolian anywhere, even if he were not half so

marked as Mr. Gladstone is by his

native Lancashire.

These remarks are by no means intended as a blowing of my own trumpet; and I desire to apologize for

so much dragging in of my own personal

experience but upon this subject one can

have had no other, except at second hand, which is worthless.

Many inconsistencies, many contradictions will be found by those who search for them, and I neither pretend

to deny or to justify such. My reply

in advance to such criticisms, is that the people are inconsistent and contradictory; that

they have only been taught by rule of

thumb, and have never been accustomed, in talk at least, to be curbed by anything at all like a rein

of law.

Inasmuch as the Introduction here following is but a filling in a gathering up of the fragments of the

pronunciation, grammar, and syntax

dealt with in the previous papers, it cannot but be somewhat disjointed and abrupt.

Listly, I commend this fruit of many years' thought and study, with all its shortcomings, its repetitions

and its mistakes, to the indulgence of

those who in their own persons have tried to record and to define a dialect in any language

whatever.

F. T. E.

FojcJtnun, February 1888.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9750) (tudalen 015)

|

INTRODUCTION.

THE following pages are intended to be the fulfilment of the promise contained in the first paragraph of

the Grammar of West Somerset, written

fourteen years ago, and so far as this Society is concerned, the work on this subject in my

hands is completed.

The few remarks I have now to make are but supplemental to that paper, and to the one on the dialect

previously published by this Society,

so that the two together are to be taken as part and parcel of this Introduction. After twelve

years', more or less, constant work on

the subject, it is satisfactory to be able to confirm what has gone before, and to feel that

there is nothing to be unsaid,

although there is somewhat to be filled up, and perhaps now that my observations are mostly noted,

it would be a good time for some other

worker to begin, and to note the many-facts

which I shall have left unrecorded, or imperfectly dealt with.

One peculiarity of our pronunciation not before recorded, as a rule, is that long a after g, sh, or k,

becomes long e, as in gable, again,

cave, scarce, scare, escape, shame, shape, share, shave, pronounced always gee'ubl, ugec'un, kee'uv,

skee'us, skce'ur, skee'up, shee'um,

shee'up, shee'ur, shee'uv, &c.

Usually, in Teutonic words long ay keeps the same sound in the dialect as in literature e. g. day,

say, way, while in French, or imported

words, the sound is much widened, as in pay, play, May (month), ray, pronounced paay, plaay, maay,

raay.

Ea of lit. English pronounced long e, is in the dialect often long a, as sea, tea, deal, heal, meal, seal, read,

lead, v. t meat, wheat, pronounced sai' t tar, dae'ul, li)ae*ul, mae'ul,

sae'ul, rai'd, lai'd, mai't, wai't,

&c., but there are many exceptions e. g. fear, beat, heat, pronounced fee'ur, bee'ut (in Devon bai't\

yi'it, &c.

Ee, on the other hand, is frequently short i, as wik, wil, stil, for week, wheel, steel, &c.

Short / is very often long e in the dialect, as bee'd, ee'f, beech, dee'ch, stee'ch, ee'nj, ee'm, pee'n, seen,

skee'n, for bid, if, bitch, ditch,

stitch, hinge, hymn, pin, sin, skin, and many more.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9751) (tudalen 016)

|

xvi

INTRODUCTION.

Readers of Nathan Hogg's poems will perceive that as in East Somerset, so in Devon, long . is much

broader in sound than with us. Our

long oa is scarcely distinguishable from literary speech. IV. Som. Devon. Literary.

broa-kt brau-kt broke

znoa-

droa- drau- throw

stoa-ld stairld stole

koa-1 kaui cold

toal taui told

Like Italian and French we drop the first when two vowels come together, or rather slide the two into one,

much more than in lit.

English, as in

vur ae-upmee = for a halfpenny, geod-

tart = good to eat.

t'aevee vau'ree = too heavy for you.

guup-m zee* = go up and see.

boa-naa-ru = bow and arrow.

O in lit. Eng. is seldom changed or dropped, nor does it influence neighbouring vowels. Compare go

away, go in, go out, go up, with our

goo war, gee'n, g-aewt, g-uup, or g-au'p.

Wuz you to the show last night? No, they widn lat me g*in 'thout I paid shillin', and I could'n vord

it. Nif I be able vor g-out doors next

week, the work shall be a-doo'd. Our Jim shall g-up and put'n to rights.

" In t'ouze” is the invariable form for “in the house." Maister home? Ees, I count a went in tome

by now. The very usual forms of

narration are, So I zess, s-I. Zoa, a zess,

s-ee. You baint gwain, b-ee? i. e. be ye. Mother's in t-'ouze. Home t-our house. Up t-eez place. Down

t-Oun's moor. Come in t-arternoon. You

can git'n in t'Hill's (t-ee'ulz). Mr. Hill t-Upton (t-uup'm) farm.

Abundant examples will be found in the text and in the Word Lists of all these varieties of vowel

pronunciation.

B, and often d, before le are not sounded we say buum'l, buun'l, mitunrl, tuum'l, tnmtrl, an" I, aam'l,

nee'ul, for bumble, bundle, mumble,

tumble, trundle, handle, amble, needle, &c.

\ ct we find a redundant d inserted between r and /, especially

in monosyllables. In Mid. Eng. this was done in world, which

md written wordle by several writers*, g. Langland, Trevisa,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9752) (tudalen 017)

|

INTRODUCTION.

xvii

&c., but this is peculiar, and its M. E. form seems to indicate from analogy of similar words in the dialect,

that at that time as now the final d

was dropped, and that the d in wordle is a redundant insertion, precisely similar to our modern

vernacular, guur'dl, maa'rdl, kuurdl,

puurdl, wuurdl, buur'dl, Baa'rdl, kwau'rdl, for girl, marl, curl, purl, whirl, burl, Barle

(river), quarrel, &c.

Words spelt alike in literature, but different in meaning, have often very distinct sounds in the dialect.

Quarrel, v. and sl>., is always kwau'rdl. Quarrel, sb. t a pane of glass, is kwau'ryul.

On the other hand differences of sound in certain literary words do not exist with us. Hear, ear, here,

year, are all alike yuur.

The following words of lit. English ending in y drop this termination in the dialect, notwithstanding

the partiality for the sound shown in

its general use as an infinitive inflection, marking the intransitive and frequentative form;

also as a diminutive of nouns in words

like lovy, deary, sweety, &c., and as a redundant, perhaps euphonic, insertion, in Foxy down,

Dartymoor, &c.

Stud for study, v. t. and /. and sb.; car for carry, v. t.; dirt for dirty, v. t.; emp for empty, v. t.; slipper

for slippery, adj.; store for story,

sb.; ice for icy, adj.

I can't think nor stud what I shall do. In a riglur brown stud. You can't car't all to once. Tommy, mind

you don't dirt your pinny. Your old

Jim '11 emp cloam way one here and there. The

road was that slipper, I thort never should'n ha corned 'ome.

Purty store sure 'nough 'bout th' old

Bob Snook's wive. I sure ee 'tis riglar

ice cold.

The form of the possessive used by a native constantly distinguishes to whom

he refers, when there is nothing in the context to show this.

[Aay yuurd Jiinv zai tu Jaa'k; neef ee ded'n lat loa'un dhai wauyts haun ee wuz daewn een uun'dur ee'd

braek-s ai'd,] I heard Jim say to

Jack, if he did not leave alone the scales while he was underneath, he would break his head.

Nothing here but the form of the

possessive shows who's head would be broken. In the literary version, the implication decidedly is that

of a threat that Jim would under

certain conditions break Jack's head. Not so in the dialect. No ambiguity would arise. The use of the

possessive pronoun his (when so

contracted) is invariably reflective, and shows unerringly that it is Jim's own head that would be

broken. On the other hand, the

opposite meaning would be just as infallibly conveyed by

b

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9753) (tudalen 018)

|

xviii

INTRODUCTION.

identically the same words, if only the his had but had ever so little stress upon it. "He'd break 'is

aid," would express that there

had been a distinct threat to Jack on the part of Jim. Another and still more emphatic form of

conveying the threat to Jack, would

be, "he'd break th' aid o 1 un," i. e. that Jim would break Jack's head, and not that his own

would be broken. We see then that the

possessive masculine pronoun contracted and

unstressed is reflective, while stressed it is objective. The

feminine possessive being incapable of

such modification would be reflective in meaning whether accentuated or not,

and thus in order to narrate the

threat it would be needful to say, "he'd break th' aid o'er." It should be noted that this

contraction of the possessive his into

a mere sibilant, is not consequent upon any influence of proximate consonants “Bill cut-s vinger”

means his own finger, white “Bill cut

ees vinger," in the absence of all context, implies some one else's finger.

Stress again in the dialect comes in to mark differences in the meaning of homonyms, which in literary

English are marked only by the

context; for instance

" Well nif thick-s to good vor me, he-s to good vor 'ee too." This use of the two forms of too is

invariable. When stress has to be laid

upon the too, in the case of over and above, it is laid not on the adverb, as in literary English, but

upon the adjective, e.g. to good, to

bad, &c., while in the sense of likewise it is always tue* good too, bad too, &c. The aesthetic slang,

quite too too, would therefore be in

violation of dialectal usage, and be unintelligible.

Another expressive difference in stress is that commonly heard in the demonstratives this, these, when

used with nouns signifying time, in

the sense of during ox for the space of.

[Aa*y aa*nt u-zeed'-n z-wik], means, “I have not seen him for a week or more," but [aa-y aa-nt

u-zee'd-n dhee'uz wik], means “I have

not seen him during this current week," dating from Sunday

last. The same applies to future as

well as past construction “Your wagin

'ont be a-do'd-z-vortnight," means, it will not be finished for a fortnight, at least while this fortnight

in literary English would mean, during

these particular two weeks.

On opening a cistern in the garden which needed cleansing, the man said to me, [u doa'n leok s-au-f ee'd

u-biin u-tlarnd aew-t-s ,] he (the

cistern) does not appear to have been cleaned out for many:. Nov. 9. 1883.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9754) (tudalen 019)

|

INTRODUCTION. xix

The demonstrative this here is often used as a phrase implying something new, or at least unfamiliar, and

out of the common run. A tenant

farmer, speaking of some repairs to the dairy window, said to me, They do zay how this here preforated

sine 's a sight better 'n lattin. This

implied that the zinc was a new thing which he had heard of, but never proved. So one

often hears sentences like the

following This here mowing o' wheat idn nit a quarter so good 's th' old farshin reapin'.

Have ee a-yeard much about this here ensilage?

This here artificial idn nit a bit like good old ratted dung, about getting of a crop way.

This here Agricultural Holdings Act idn gwain to do no good to we farmers, nif we do keep on having

cold lappery saisons.

This here bringing over o' fresh meat from America's gwain to be the finisher vor we; beef's 'most the

only thing can zil like anything, and

hon that's a-hat down, t'll be all over way farmerin.

In each of these illustrations this here has the meaning of this new-fangled.

In adjectives we have a kind of hyper-superlative used chiefly for great emphasis, in which the

superlative inflection is reduplicated,

with or without most as a kind of make-weight.

I zim yours is the most beautifulestest place ever I zeed. The purtiestest maid in all the parish. The

most ugliestest old fuller, 'sparshly

(especially) hon 'is drunk. The irregular adjectives have the superlative inflections superadded

almost regularly to their ordinary

superlatives. The bestest drink in the town. The wits' tees old thing vor falseness. The mostest ever I

zeed, &c.

Some auxiliary verbs have no inflection in the past tense, in the dialect, e. g. to let (permit); to help;

consequently instead of the principal

verb being as usual in the infinitive mood as, I let him see; I help(d) him do it; I let her have

it; I help(d) mount him, we use the

past tense of the principal verb instead of the infinitive, and so the past construction becomes

unmistakable.

May 28, 1883. A man said to me respecting a new tenant for a cottage he was quitting He come to me and

ax whe'er wadn nother 'ouse to let,

and zo I let'n zeed the house to once. This

man or any other native would say I let her had'n; I help 'in do'd it; I help mounted'n; I help

measured'n for a new suit o' clothes;

you mind you help me cleaned out thick pond. See HUTCH 3.

Inasmuch as [diid-n] did not, is a present conditional form as

b 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9755) (tudalen 020)

|

INTRODUCTION.

follows the

being alike, it seeme needful add ^ ^^ w

It 8 has over and over been gwen of ^ yerbs

exception (* VIII. A. i, P- 4), ^ ari P howeve r not prev.ously formed by the prefix a [u]. A pecuUa y ^ ^

noted *at very frequently tospre g m

to which it belongs by the mserUon ^^ Joe> fl

phrases like the **>*-* the zaddle. I told ee how ' a new

.

fresh sharp the zaw 1 e'd a new ^ ^ was fl oncommon

you was a vrong diiec ed.” daned out .

vexed o- it. I 'sure you th ^ w U w ^ ^ ^ afte the

In these sentences the words u

may suggest something as

In some cases and by some mdmdua ^te P

th before the adverb as above and ag am befo ^

aions and

verb, have ^ injection ^ referred to

in p. 51 of W \ S ' GraM \ ' -, a ii ud ed to by other

but i; construed with all the persons except ****'* to

They zess how they workw to factory. Her [ai tus] to

vast by" half. Our Handy always berto so long's any strangers b about We loota vor the death o' her every

day. They [chee ik ,] chairmak,-(i. e.

work at chairmaking) n,f they can cct

it In all these cases the inflection distinctly conveys a continuance of

action; and in certain districts is a commoner form

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9756) (tudalen 021)

|

INTRODUCTION.

XXI

than the well-known periphrastic one, so fully illustrated in W. S. Gram. pp. 50 79.

The pronoun it is sometimes emphasized and is then pronounced [ee't], but its use is uncommon, and only

heard in such sentences as I tell ee

it is [ee't arz], where both words are stressed by way of asseveration.

All collective nouns, even if plural in form, take a singular construction

and take // after them. Zo you bought all th' apples, did ee? well I don't know hot you be gwain to

do way //, I 'ant a-got no room.

They zess how he bought a lot o' beast off o' Mr. Bucknell, and V idn a paid vor. I baint gwain to turn

things in to market, nif can't zell

it.

As a neuter pron. it is unknown to us in W. Som., while in Devon it is common. They say, You've

a-braukt /"/ then, to last. Hath

her a-lost it? We say, You've a-tord', Hath her a-loss'?

The possessive form its is quite unknown; his or her in the forms [ee*z, uz, -s; uur, ur,] are invariable.

Indeed, one would like to know with

certainty, when its was first used in literature; but for this we must wait for the new English

Dictionary.

The Chapter of Wells, a presumably educated body, wrote to the Bishop of Winchester in 1505 about the

drainage of their contiguous land

cause the floodgate of o r said myell to be pulled up, so that the water

shall haue his full course. Reynolds,

Wells Cathedral, A pp. iii. p. 217.

The contraction of as to a mere sibilant, sometimes hard, sometimes soft, in

whatever its connection, is not only usual, but without exception, even when it begins a sentence.

'z I was gwain to St. Ives, &c., would be the way it would be pronounced, but of course this would not be

the vernacular idiom. As in the sense

of when, at the time that, or just in the manner that, would all be expressed by ems.

I zeed'n eens (as = when) I was gwain home to dinner.

Her was a-catchd nezactly eens (as == at the moment) her come in the door.

Twad'n nit one bit o' good to sarch no more, eens I told'n tho' (as = just as I told him at the time).

The conjunction as, however, enters very largely indeed into west country speech. For just as scarcely a

remark can be made without a simile,

so in the construction of those similes as is to be found in a full half i. e. in the phrase

same as [sae'um-z]

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9757) (tudalen 022)

|

xxii

INTRODUCTION.

alternating with its synonym like. I can't zee a pin to choose in em, one's so bad'* tother. Same'* the crow

zaid by the heap o toads, they be all

of a sort.

Again as is used almost as often in connection with though, which we pronounce off or thoff, as shown

in the example to illustrate

contraction of these (ante p. xviii).

Tid'n /off I'd a-do'd ort agin he, nor neet /off anybody was a-beholdin to un, then anybody must put up

way 'is sarce.

As is never used in the south-west, like it is in many districts, for a relative.

" Twas him as done it," could not be said by a native of the Western counties. (See EVANS, Leicester Gloss,

p. 26.) Neither would it be used in

the sense of like, or in the same manner as. We could not say, “He shall reap as he has

sown," our idiom would be a

complete paraphrase" Eens he've a-zowed, zo sh'll er rape."

As, I may venture to say, is never used before if; as if is never heard, but always, in the way before

illustrated, our idiom is s-off, or 's

thoff \. e. as though. Neither is it found in such refined company as for or to.

In phrases like “As for t\\a\. matter," or "As to what you say," our idiom would be “zo var's that

goth," or “consarnin' o' what you

do zay." The expression "as well" in the sense of also, likewise, and "as yet" i.e. up to

this time, have not yet filtered down

to us. We could not bring our tongues to utter such refinements as, “Bring me some tea and a

little milk as well" “I have

never come upon such an instance as yet" but we should say, "a drap o' milk 'long way

it," “sich a instance never avore."

The double use of as i. e. before and after the adjective or adverb, which is now the polite form, is

never heard in the dialect; as well

as, as big as, &c. are invariably so welFs, so big's, &c.

The preposition of is a peculiar instance of change and contraction under

certain fixed conditions, which appear hitherto not to have attracted attention.

1. It invariably drops its consonantal ending when followed by a consonant, and becomes a mere breathing

u.

[Lee*dl beets u dhingz. Dhai bwuuyz du maek aup u suyt u murs-chee.] A bag o' taties. I be that

there maze-headed I can't think o'

nothin'.

2. It drops its consonantal ending, and usually becomes changed to long o sound, when followed by a short

vowel, provided that vowel is the

initial of a syllable.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9758) (tudalen 023)

|

INTRODUCTION.

XXlll

He said he'd break th' 'ead o un. He could' n never do it out o* is own head. There was vower or vive o'

us. Trode 'pon the voot o 1 'er. I

'ant a-got none d um (or contracted to <?'m).

3. It drops its consonant and becomes of medial length when standing at the end of a clause.

'Tidn nort vor to be 'shamed o\ Cockney 'Taint nothink to be ashamed on. They chil'ern o' yours be

somethin' vor to be proud o\ What be

actin' o 1? is the ordinary method of saying,

What are you doing? What be a tellin' c?? = What are you saying? What d'ye tell o'! is very common;

indeed it is the usual form of You

don't say so! indeed! oh, brave, &c.

4. Of retains its consonantal ending when followed, by a short vowel standing alone, like the indefinite

a, even though in rapid speech it

sounds like the initial of a syllable.

[Lee'dl beet uv u dhing.J Gurt mumphead of 'a fuller. Bit of a. scad, I count.

5. It retains its consonantal ending when followed by a long vowel.

Nif on'y I'd a-got a little bit of ort vrash like. Her's about of eighty, I count. This would more commonly

be About of a. eighty, and so accord

with Paragraph 4. Comp. 'Boux o' TWENTY.

Her didn want nort of he.

6. Emphatic of is common, and loses its consonant.

[Kaa*n tuul eentaa'y hautiivur faar sheen dhai bee oa'~\ is the usual form of, I really cannot give you a

description of them. See INTY.

I vound these thing 'tis a 'an'l oaf o 1 something, but I can't tell what 'tis o\

Certain verbs in the dialect take Rafter them, which in lit. Eng. have at, or else require no preposition to

follow them. To /aug/i, always is

followed by of.

Hotiver be larfin' o'? is vernacular for What are you laughing at?

Troake 1 What are you laughing at? Plase, sir, I wad'n larfin' o* you. Well, I did'n zee nort to larf o 1

' You no 'casion to larf c> they,

gin you can do it better yourzul.

To touch always takes Rafter it.

I zaid I'd hat down the very fust man that aim to tich o' un.

Tommy, don't you tich o' thick there hot ire, else you'll scald yourzul.

Her thort herzul ter'ble fine, sure 'nough, but nobody wad'n a-tcokt in didn lie in her burches vor to

tich of a, rale lady.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9759) (tudalen 024)

|

INTRODUCTION.

i f

In this last, touch has the force of approach, m the sense

imitating or counterfeiting.

// a/stakes *' after the participle.

Who be you watchin' o'? I baint watchin o you (9, is never used for ,/ (as in example No

3); indeed, as a preposition it is

nearly unknown. Its use is almost confined to

adverb as in put on, go on, straight on, &c.-but of this later

Before cardinal numerals the dialect retains the indefinite adjective *, while the literary speech

retains it only before nouns of

number, such as dozen, score, and certain of the numerals which have become such-*^. hundred, thousand,

million, &c. In the dialect,

however, the use is apparently subsiding, as it is now generally confined to those cases where the

number is rendered indefinite by the

expression about or more than.

How many were there? Au! I count there was about of a dree or vower and twenty. Were there really

so many? Well, I'll war'nt was more'n

a twenty o'm. So we should always hear

"about of a ten, of a fifteen," or any number, and the same

with respect to more than.

The same form is found in Luke ix. 28, “And it came to pass about an eight days after these

things," except that in the modern

dialect we drop the euphonious n in the article and insert of after

about.

About in this sense is always followed by of, and very frequently the indefinite a is prefixed to nouns of

time, as I sh'll be back about of a

dinner-time. He said he'd get'n ready

about of a Vriday. Whether these

latter instances may not be contractions of at or on, I am unable to say, but extended to

about of on Friday, about of at

dinner-time, they seem awkward.

Again, the same form is used after about, when “the time of day” is spoken of.

I sh'll be home 'bout of a zix o'clock.

About is a curious word in the dialect. It is very commonly used in the sense of “for the purpose

of." I heard a farmer say,

"This is poor trade, sure 'nough, 'bout growin' o' corn,"

which being interpreted means, “This

is poor stuff of soil for the purpose

of growing corn upon." Here was by no means an unintelligent man; he had not a very marked intonation or

brogue, and he used words to be found

in every dictionary, but out of his own

ict I think his words would have been totally misunderstood,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9760) (tudalen 025)

|

INTRODUCTION.

XXV

even though his hearer had the benefit of the Society's great Dictionary with Dr. Murray himself at hand

to help him.

The late Rev. "Jack" Russell (see Life, Bentley, 1878, p. 242)

said, "The hounds are as good as

ever they were; but fed on that wishy-washy trade, I'll defy them, or any hounds on earth, to kill

a good fox."

It is usual to say, “Shocking bad weather 'bout zowin' o' whate," “Purty tool this here, 'bout cuttin' o'

timber way."

A boy who is to be thrashed, is to have a stick “about his back."

An old man, who alas! was frozen to death, said to me of some spar-gads which he was making into spars,

“Gurt ugly toads, the fuller that cut

'em ort to a-had 'em a-beat about the gurt head o'un."

In both these last instances about neither means upon, or around, or against, but a compound of all three,

with an implication of violence to

boot. Of course we use about in the ordinary literary meanings.

Another curious preposition is used only in the dialect in the contracted form 'pon, for the on of lit.

English. In many cases upon, which is

first expanded to upon the top of, has become contracted out of sight, or

rather improved off the face of the earth.

We should not tell a person to <c put it down upon the table," but to “put'n down tap the table." “I

saw him swinging upon the gate” would

be, “I zeed'n ridin' tap the gate." This idiom is used throughout the West. Nathan Hogg in

his letter on Gooda Vriday says

An I'll tul thur tha vust thing I'll du ta be zshore Pitch et in tap tha urch za wul as tha

pore.

Again in Bout tha Balune

Poor vellers! they always wis vond uv ort vresh, Wen they liv'd tap tha aith, an like us wis

vlesh.

This word tap is all that remains of the pleonastic form “upon the top of." When upon is used, it

often has up or down before it, just

as under takes down or in to complement it.

You must git a fresh sheep-skin and put-n up 'pon the back o' un. This was said by a farrier as part of the

treatment for a sick cow, which was

lying down unable to stand. (Nov. 1883.)

I don't want no trust, I always pays down 'pon the rail.

Plaisters, poultices and such-like applications have to be "put up” to the part.

I was a-forced to put a blister up to his chest.

I put the lotion up to his knee, eens you ordered me.

The preposition to is frequently omitted before the infinitive

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9761) (tudalen 026)

|

INTRODUCTION.

mood, especially so before the infinitive of purpose, which, as in French always takes/"" before

it. 7S na g*>- vur due't,] you know

he did not mtend

10 tfatert swain same purpose vor spake to the jistices vor me [Yue noa -\vaa-l vur /ai aew yue zeed

mee',] you (have) no need

to say that you saw me.

[\ay bun aup-m taewn vur bespark tue nue pae'ur u bue'ts, biid dhoa 1 Tum Ee-ul waudu au'm, bdd uur

zaed aew ee shd uurn daewn tue

wairns,] I (have) been up into (the) town to

bespeak two new pairs of boots, but old Jim Hill was not at home, but sht said he should run down at once.

It will here be noticed that in the two last examples the verb hart is omitted, and in similar negative

expressions it is generally

so left out.

[Yue noa- kizlnin,] for you hare no occasion, is very common. So the perfect tense of fc be (omitted from

my Grammar) is, I bin, or I've a-bin.

Thee's a-bin. He bin, or he've a-bin. We bin, or we've a-bin. You bin, or you've a-bin. They

bin, or they've a-bin. The preposition

to, if sometimes omitted in the dialect, is more often used redundantly. Certain adverbs of

place seem to require it as a

complement, and in these cases it comes always at the end of a sentence or clause.

I can't tell wherever her's a-go to. Where's a-bin and put the gimlet to! I can't think wherever they be

to.

Again, to not only is always used for af, as fully explained in JJ". Gram. p. 89, but the same

preposition has to do duty for in. Her

do live A? Wilscombe, to service, and we zend vor her, vor come home to once.

Mr. Burge to Ford zaid to me to zebm o' dock last night, eens Mrs, Jones to shop was dead to last, and

they zess how her keept on to work to

her lace-making up home to her death, to the very least dree hours a day. Jones, he was to

skittles in to Half Moon hon her died;

he don't care nort 't-all about it; he's so good hand to emptin' o' cloam 's you'll vind here and

there. Her's gwain to be a-buried to

cemetery to dree o'clock marra /'arternoon.

So also to is used in some cases before the gerund. I've a-tookt all Mr. Jones's grass to cutting. They was

a-tookt purty well to doing, 'bout

thick there job.

To is frequently heard where in would be used in standard English. I bide to Lon'on gin I was that

bad I could'n bide no longer.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9762) (tudalen 027)

|

: - . 7 1 - Y: .::

and solely for die very pm

'. ~. ~ .~7 ':'. 2

is by *r tbe

I com'd in *. I

"On

A I* IT EIT - I IT

accidental, would say, under die do it

^ pnrposs” <L intentiooally . the

analogy of the literary asleep.

The preposition in. often has die meaning of / or >&r in

nection with money or price.

They ax me TOT to gee /* TOT the job, zo I gid im TOT pottin' npo* die wall, bnt Lor! I conkf n *ord TOT

do' t no he've a4ookt it wr.

To "grew" means "to tender"; to give

In speaking of particular seasons, it is Tery nsoal to duplicate day when it is desired to emphasize

Twas Lady-day day beyond aU die days in the wonfl. Herll be Tifteen year old come Mechehnas-day day.

I mind your poor father died 'pon

Kirsmas-day day. They zess you can hare

possession 'pon >idsnmmer-day day.

Again at Whitsuntide it is usual to speak of Wkiiism -Sanvfef, White* Monday, Whiten Tuesday ^ &c,

In constructing oar sentences, die subject is very often placed at the end of the clause, or at least after

the predicate.

Idn never gwain to get no better, my poor old urn man, I be afeard. Do go terr"ble catchin', I

zim, thick 'oss. Also set PLATTY.

So also the construction, whether plural or singular, depends on the idea, and not upon the form of die

noun. For example sub (soap suds) are

plural in lit Eng., but in the dialect precede a verb in the singular, while broth on the

other hand is always plural.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9763) (tudalen 028)

|

xxv iii

INTRODUCTION.

Things, meaning cattle or vermin, pinchers, tongs, stairs, all take verbs in the singular.

By way of bringing the peculiarities of our dialect into direct contrast with the Midland, the basis of

modern literary English, I have taken

Dr. Evans's Leicester Glossary, and have distinctly set out below many forms therein given which

are not known to us, for the reason

that it is often as important for a student to know what is not done in a district, as to be

informed on points which many

localities have in common. I have also noted others common to both localities.

1. Nor, meaning than, common elsewhere, is not heard in the West. “Yourn is better nor mine” could not

be said by a Somerset or Devon native.

2. The uninflective genitive (see Evans's Leicester Gloss, p. 22), “The Queen Cousin," is unknown.

3. The redundant article used in Leicestershire (Ib. p. 23), with such (e.g. It is a such a handsome cat), is

never heard.

4. The (Ib. p. 23) is not omitted where used in literary English. On the contrary, it is often used when not

needed in literary construction. With all diseases it is used

The cheel 've a got the measles the scarlet fever, &c. I've a-got the rheumatic ter'ble bad. Her's bad a-bed

wi' th? infermation o' the lungs.

Also before trades, as

He do work to the taildering. My boy 've a-larned the calenderin. We Ve a-boun' un purtice to the shoemakerin.

In these latter cases the form is that which would be used in speaking to a superior, and its use implies

that the person addressed is not

familiar with the trade. Indeed, the has a force analogous to this here, as before explained in the sense

of unfamiliar^ new-fangled, or

supposed to be so by the person addressed.

Again, in speaking of any person, whenever the description old or young is prefixed, it is always the old,

the young.

I yeard th' old butcher Davy zay how the young farmer Hawkins had a-tookt a farm.

This form is invariable in the Exmoor Scolding.

The (Ib. p. 23) is never omitted in the West before a thing to which attention is called. We should not

say" Look at fire," as in

Leicester, but “Look to the vire."

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9764) (tudalen 029)

|

INTRODUCTION.

xxix

5. Better seems to stand for more everywhere. We say I'd a-got better'n a dizen one time.

6. The inflections of comparison can be added to all participles as well as adjectives proper. (Ib. p. 25.)

There idn no more gurt vorheadeder holler-mouth in all the country.

'Tis the most pickpocketins (/". e. pickpocketingest) concarn iver you meet way in all your born days.

7. Them (Ib. p. 26) is never used as a nominative, except in the interrogative forms, Did 'em? have 'em? be

'em?

We could not say "them books" either as a nominative or accusative our corresponding demonstrative

is they.

8. We is not heard as a possessive (Ib. p. 26). Occasionally, to children, you and he are used as

possessives Tommy, gi* me you 'an.

Where's he purty book?

Hisn, hern, ourn, yourn, theirn, are not heard.

We is not used reflectively. We should say, We'll go and warsh urzuls, and get ur teas; never warsh we.

Its does not exist in the dialects of the West. If the need arises for a neuter possessive pronoun, which can

be only in respect of abstract or

indefinite nouns (see W. S. Gram. p. 29), the form is o' it It must never be forgotten that all nouns

capable of taking a before them are

masculine or feminine (very few of the latter). “It was not a bad sermon, though its drift was

uncertain," would have to be

paraphrased, “The sarment wadn so bad, but the manin o' un wadn very clear."

9. What is with us, as in Leicester, used as a relative redundantly (Ib. p. 26). 'Tis the very same 's'w/iaf I

told 'ee. They baint nit quarter so

good as they, what I had last.

10. T/iis-r\, that-K, &c. (Ib. p. 27), are never heard, but we often add a genitive inflection on to the

demonstratives this, thick.

[Dhee'uzez bruVtez bee deep'ur-n dhiks, bee u brae'uv suyt,] this-^ breasts be deeper than thick's, by a

brave sight.

11. That (p. 27) is not used in such phrases as / do that, I can that, &c. We should in such cases say /

do zo, but the expression would sound

pedantic or affected in native ears, and savour too much of the board school.

12. Sen (p. 27) or sens are unknown with us. Self, whether alone or in combination, is always zul.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9765) (tudalen 030)

|

XXX

INTRODUCTION.

13. We know nothing of the en (p. 27) added to monosyllabic verbs we even drop it where found in lit.

Eng. e. g. to hark, to wide, to hard,

to fresh, to thick, to quick, to ripe, to hap, &c.; but in words where the en is part of its

original form, as in token, nasten, we

retain it So also we drop the er in to lower.

I heard a man speaking of rats, say, “I reckon I've &-l(ru?d they a bit." And another man who was

levelling for me a short time ago,

said, “Must low thick there 'ump ever so much."

It will be noted that we in the West do not make any use of the past participial inflection en, as in

beaten, drawn, flown, so common

elsewhere. A-knowed, a-zeed, a-gid, a-do'd (sometimes a-doned), a-tookt, a-forsookt, a-beat, a- vailed, a

stoled are our forms. I am inclined to

think a-dorid is quite a recent development, yet adjectivally we constantly

use the form, bought^ bread. (See p. 232.)

14. We should not comprehend can or could in the infinitive, to can, to could (Ib. p. 31). We should simply

leave out the relative “He's the man

can do it;” and in the other sentence 4 ' I used to be able vor do it in half the time."

15. What Dr. Evans calls the redundant "have" (p. 31) in the pluperf. conditional, is nothing but the

old past participial prefix. "Nif

I'd a-zeed 'n” would be our form.

I agree with Dr. Evans that such forms as Where bin I? How bin you? are spurious creations of dialect

writers (see Preface, p. v), who have

perhaps learnt a little German, but do not know other than literary English.

1 6. No such negative form of verb as havena (p. 31), or hanna, wasna, worna, &c., are known in the

West.

I am astonished at the existence of fourteen forms of “I am not," as given by Dr. Evans (p. 31).

The W. S. is as copious s any dialect,

and it knows but two forms, I baint, and the

emphatic / be not. Of course “I ain't” is heard, but only among those who talk fine, and speak the Cockney

dialect learnt at board schools.

17- We never use on instead of from or of (p. 32). We say a >t <tm, not a lot on em; had'n vrom

me, not had it on me We the word

Rafter buy. \ bought thick oafti Jim Smith '

:ore mentioned, before nouns denoting points of time we

use on, though contracted to a mere breathing. Your

1 be a-dood a Zadurday night, would be our regular form -

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9766) (tudalen 031)

|

INTRODUCTION.

XXxi

but occasionally such an expression might be heard as “trying to mend the pump Zunday."

1 8. I think Dr. Evans' instance (Ib. p. 32), "the Quane to yer aunt," not to be a substitution of to

for for, but to be precisely similar

to the ordinary phrases “without a coat to his back," “no key to the lock," or to the Scriptural

language, "We have Abraham to our

father."

In preparing this work for the press, I had made some considerable progress

before it occurred to me that the number of words and syllables dropped or omitted, and of

others inserted, was very considerable

as compared with standard English, and the recurrence of the same form in a variety of the

illustrative sentences under revision,

decided me to begin to note these systematically, with the view of bringing them together in such a

shape that fresh rules of syntactic

construction, as well as of pronunciation, might be induced. No attempt is here made to show whether

these peculiarities are right or wrong

abstractedly, but merely to contrast them as they are with their counterparts in lit.

English. However imperfect the result

of these notes, it may not be considered waste of space to insert them here. In some cases the

omission is confined to that of a

single word in some particular phrase; but when so noted it will be understood, unless otherwise

stated, that the form noted is that in

such common use as to deserve the term always.

I first take connective words or parts of speech, and then go on to special idioms, and finally to omissions

of initial or final syllables and

sounds.

Beginning with distinguishing adjectives, it is very common to find both a and the omitted. It must be

borne in rnind that an even before a

vowel is unknown. (See W. S. Gram. p. 29.)

1. A is dropped very frequently but not always before the adjective or adverb in descriptive

sentences such as

'Twas terr'ble close sort o' place, I zim. Mr. Jones is mortal viery man. See lllust. QUICK-STICK, KIN.

2. A is omitted before bit or quarter when used as a fraction. Thick there idn quarter zo goods 'tother.

Wants quarter to

one, an' there idn no sign o' no dinner not eet. See also PLATTY, SNOUT, RUNABOUT.

3. A is dropped after/i?/-.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9767) (tudalen 032)

|

INTRODUCTION.

Nobody ont do

I've a-keep the market vor number o' years,

nort vor man like he. See PINCHFART, SPAT.

4. A is dropped after such, nearly always.

Jis fools' he off to be a-starve to death! You ant a-zeed no jis noise 'bout nort in all your born days. See

GRUBBER 2, JITCH, PANTILE, RUMPUS,

RUSE, WORD o' MOUTH.

5. A is dropped after so good in comparative sentences.

I zay 'tis zo good lot o' beas' as I've a-zeed's longful time. See LIKE i.

6. The is often omitted before same as, a phrase which has become the regular idiom for like or just as.

I've a-do'd same's father do'd avore me. See JOGGY 2, OUT 3, RUNABOUT, OFF 2, SPUDDLY.

7. The is always omitted before words which, though proper names or com. nouns, serve to point out

position or occupation, precisely like

the literary I am goin' in to town as we say, not of London only, but of everywhere.

I be gwain vor zend to station to-marra.

He's that a-crippl'd, can't put his voot to ground.

I zeed'n in to Board (Guardians), but I could'n come to spake to un.

We always say send “to mill," “to lime” (kiln), “to shop," “to farrier," "to smith,"

&c. for anything wanted.

The cows be down to river. I be gwain down to sea.

To drive a dog out, we always say Go to doors! A publican would say, Nif you don't keep order, you'll

be a-put to doors. This phrase implies

more than omission of the; it stands for out of the. See To 2.

Illustrations of various uses will be found as follows under HOME TO, MEET WITH, HAPSE, POST OPE, RUSE

2, RAKE ARTER, SIDELING, TIMES i,

HARREST DRINK, IN HOUSE, WAD.

Before the names of public-houses the is always omitted, and also in the com. phrases, to back door, to

door, to hill, to load, to rick, to

road, to vore door, to lower zide, in house, up in tallet, &c.

I zeed'n in to King's Arms. See PEDIGREE, POOR 3, RUSE 2, STEAD.

The phrase tap is peculiar, being a contraction of upon the top of, and hence tap in the dialect has become

a regular preposition. Ste TOP, RUSF

i.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9768) (tudalen 033)

|

INTRODUCTION.

XXXlll

Where's the pen an' ink a-put to? I left it tap the table nit quarter nower agone!

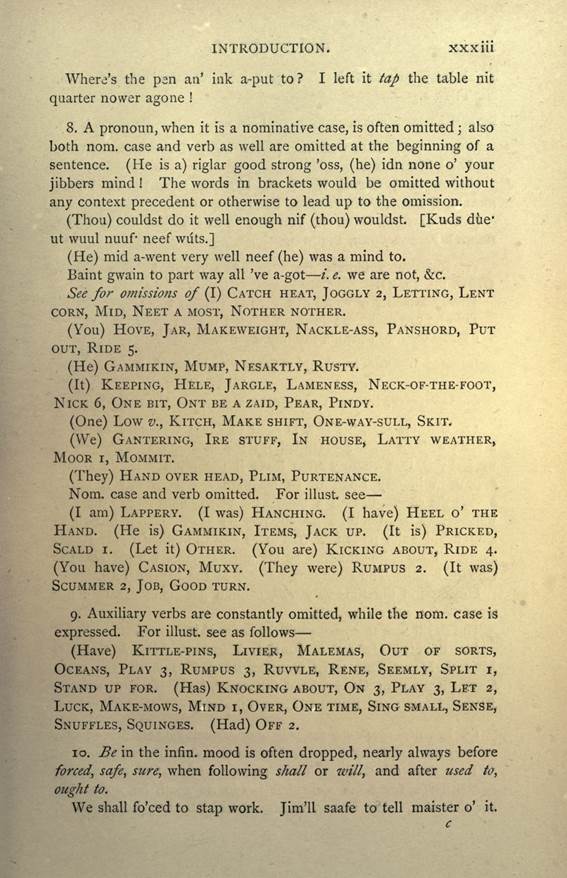

8. A pronoun, when it is a nominative case, is often omitted; also both nom. case and verb as well are omitted

at the beginning of a sentence. (He is

a) riglar good strong 'oss, (he) idn none o' your jibbers mind! The words in brackets would

be omitted without any context

precedent or otherwise to lead up to the omission.

(Thou) couldst do it well enough nif (thou) wouldst. [Kuds due' ut wuul nuuf 1 neef wilts.]

(He) mid a- went very well neef (he) was a mind to.

Baint gwain to part way all Ve a-got /. e. we are not, &c.

See for omissions of (I) CATCH HEAT, JOGGLY 2, LETTING, LENT CORN, MID, NEET A MOST, NOTHER NOTHER.

(You) HOVE, JAR, MAKEWEIGHT, NACKLE-ASS, PANSHORD, PUT OUT, RIDE 5.

(He) GAMMIKIN, MUMP, NESAKTLY, RUSTY.

(It) KEEPING, HELE, JARGLE, LAMENESS, NECK-OF-THE-FOOT, NICK 6, ONE BIT, ONT BE A ZAID, PEAR,

PINDY.

(One) Low v. t KITCH, MAKE SHIFT, ONE-WAY-SULL, SKIT.

(We) GANTERING, IRE STUFF, IN HOUSE > LATTY WEATHER, MOOR i, MOMMIT.

(They) HAND OVER HEAD, PLIM, PURTENANCE.

Nom. case and verb omitted. For illust. see

(I am) LAPPERY. (I was) HANCHING. (I have) HEEL o' THE HAND. (He is) GAMMIKIN, ITEMS, JACK UP. (It

is) PRICKED, SCALD i. (Let it) OTHER.

(You are) KICKING ABOUT, RIDE 4. (You

have) CASION, MUXY. (They were) RUMPUS 2. (It was)

SCUMMER 2, JOB, GOOD TURN.

9. Auxiliary verbs are constantly omitted, while the nom. case is expressed. For illust. see as follows

(Have) KITTLE-PINS, LIVIER, MALEMAS, OUT OF SORTS, OCEANS, PLAY 3, RUMPUS 3, RUVVLE, RENE,

SEEMLY, SPLIT i, STAND UP FOR. (Has)

KNOCKING ABOUT, ON 3, PLAY 3, LET 2,

LUCK, MAKE-MOWS, MIND i, OVER, ONE TIME, SING SMALL, SENSE, SNUFFLES, SQUINGES. (Had) OFF 2.

10. Be in the infin. mood is often dropped, nearly always before forced, safe, sure, when following shall or

will, and after used to, ought to.

We shall fo'ced to stap work. Jim'll saafe to tell maister o' it.

c

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9769) (tudalen 034)

|

xxxiv

INTRODUCTION.

Thick 'oss'll sure to kick. Things baint a bit same's they used to.

See TIME i.

Bet es won't drenk, nether, except ya vurst kiss and friends. Ex. Court. 1.

534-

(After shall] STAND-TACK. (After wilt) TOP-SIDED. (After ought to) MISTRUST.

(Before sure) GIFTS, HEFT sb. t HORCH, LAB, JAKES, PEASE ERRISH, QUAINT, SORE FINGER, TACKLING,

SHOD.

(After used to) GRIP sb. t JUMBLE, SHAKE 2, LIE ABED, LONG-DOG,

OUT-DOOR-WORK, PITCH 4.

11. Relative pronouns are very often omitted. See W. S. Gram. pp. 32, 41.

There's a plenty o' vokes can 'vord it better'n I can. Tidn he can make me do it, and that I'll

zoon show un. I know very well tvvad'n

my boy do'd it.

Was there no other place might serve to worship in.

1642. Rogers, Naaman, p. 535.

See GENITIVE, LOOBY, POKE 5, SHARPS, SNAP, UNDECENTNESS.

12. Webster says, "There, is used to begin sentences, or before a verb, without adding essentially to the

meaning." So much do we feel

this, that we very often leave it out when it would always appear in literary English. In negative

sentences this is nearly always the

case. Idn nit a mossle bit a-lef. That there's the very wistest sort is. On't be no cherries de

year. Wad'n but zix to church 'zides

the pa'son. Was more pigs to market' n ever I zeed avore. They holm-screeches be the

mirscheeviusest birds is. See

COWHEARTED. The same may be said of the adverb when.

I can mind the time very well, could'n get none vor love nor money /. e. when /could'n.

The day'll sure to come, you'll be zorry o' it.

See POPPLE, HEART 2, JOBBER, MANSHIP, MOLLY CAUDLE, MUNCH, MATH, ONE WITH TOTHER, PECK, PROOF,

TIMBER DISH, GETTING, PROACH, GLARE,

LEW, QUADDLY, Loss, MILL, MOGVURD,

RUBBY, RlGHTSHIP, REVEAL, RlNE, THROW 3.

T 3. In sentences or clauses, with so or as qualifying another adverb, we very commonly omit the first of these

connective words Vast as I can drow

the stuff out, 'tis in 'pon me again. Quick's ever her could, her brought the spirit, but twadn no

good, he wadn able vor tich o' it. See

LEGGY, MAKE HOME, MANNY, LONG-DOG 2,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9770) (tudalen 035)

|

INTRODUCTION. XXXV

MUTTERY, MASH, PAY, RISE v. /., SACK i, STIVER. These examples seem to be all uses of soon, but

the same form is common with many

other adverbs.

I tell ee tis vright's ninepence. Thick there cask is zweet's a nif See SCAMBLE i. So as, i. e. in such a

manner as, is often omitted; for

example see PAPERN.

14. In phrases denoting the same time or position, the connecting prepositions and adverbs are often omitted

before and after same.

I never didn think to meet ee, same place I zeed ee to, last time I was yer-long /. e. at the same place as.

Her zaid her never widn have no more to zay to un, same time, nif I was he, I widn bethink to try again.

See RAMSHACKLE.

Where in lit. English we should draw a comparison by using like, or in the same manner as, in the

dialect we constantly use the phrase

same as, omitting the words just the, or exactly the.

Thick old fuller! why he's same's a old hen avore day. That there's same's the young farmer White do'd.

See MAZE i, REAM 2.

15. After just upon, we omit the connective words, the point of, the act of, and the sense must be inferred

from the context.

The doctor was jis 'pon gvvain, /. e. just upon the point <?/" going. The tree was jis 'pon vallin, hon a puff o'

wind come and car'd'n right back

tother way. Nif her wadn jis 'pon lettin go the bird, hon I clap my 'and 'pon the cage. See LEB'M

O'CLOCKS.

1 6. All, is regularly omitted in that commonest of phrases "But everything" (q. v.).

I baint gwain gatherin (/. e. collecting subscriptions) there no more. I 'ad 'n hardly a-told'n my arrant

vore he begin nif he didn call me but

everything; and I hadn a-gid he no slack whatsomedever.

17. The words in comparison with, or compared to, as used in a literary sentence, would be omitted by us.

Mr. Piper's proper near now, sure 'nough, what he was, cant git a varden out o' un /. e. compared to what

he was. Our roads be shocking bad,

what yours be in your parish i. e. in comparison with what yours are. This is not a mere

looseness of speech, but the common

idiom. See TAFFETY, SLACK 4.

1 8. After numerals it is very common to omit the description of price, weight, or quantity of the articles

referred to, as in the literary

hundredweight, leaving it to be inferred by the context or custom

of the market what integer is spoken

of.

c 2

XX XVI

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B9771) (tudalen 036)

|

INTRODUCTION.

You cant buy very much of a 'oss less'n forty/, e. forty pounds. I gid fifty-vive apiece for they there

couples dree mon's agone, and now they

baint a wo'th 'boo forty-eight/, e. shillings. They yoes to fat, be 'em! why they baint not no more'n eighty

apiece else they be vive hundid!/. e.