|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4320) (tudalen ii)

|

ii

THE

GENTLEMAN'S MAGAZINE LIBRARY.

The

Gentleman's Magazine Library

Dialect, Proverbs and Word-Lore

A

Classified Collection of the Chief Contents

of “The Gentleman's Magazine “from

1731-1868

Edited by

George Laurence Gomme

London

Elliot Stock, 62 Paternoster Row 1886

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4321) (tudalen iii)

|

iii

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4322) (tudalen iv)

|

iv

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4323) (tudalen v)

|

v PREFACE.

T UST at

the time when all students are welcoming the first part

J

of that

colossal work, A New English Dictionary on Historical

Principles,

brought out by the Clarendon Press under the care of Dr. Murray, I venture to

think that the contributions to the old Gentleman's Magazine, collected and

reprinted in this volume, will form an acceptable addition to the word-books

already on the shelves of most libraries. I am anxious to impress upon the

mind of readers that this volume, like its predecessor on “Manners and

Customs," does not pretend to be anything more than a collection of

material for future use a brick towards the building up of the great English

word-book; it does not pretend to be complete, except so far as its original

authors have made it, and its accuracy is dependent upon the varied skill and

learning of the writers who have contributed to the pages of the famous old

magazine. Its chief merit, if I mistake not, will be found to consist in the

local knowledge and information which is so abundantly shown throughout its pages,

and which is now so rapidly becoming impossible for the modern student to

attain. The eighteenth century scholars, not so skilful as those who have

lived in the times of comparative philology, have still done some good work

in recognising the value of the material that was to hand; and it is not a

little remarkable that so

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4324) (tudalen vi)

|

vi

Preface.

popular a magazine as the Gentleman’s undoubtedly was should have found room

for those specimens of dialect which we of this age so gladly reprint and

re-edit. Another merit I trust I may claim for this volume. The compilers of

the New English Dictionary, and all researchers into the word-history of the

English language, will doubtless have thought it necessary to examine the

Gentleman's Magazine, and this lengthy task may be lightened by the

possession of this volume of collected reprints. Again, the early pioneers of

the English Dialect Society examined the volumes of the original to gather

together the references to Dialect, and besides having these communications

printed here in extenso, there will be found much more information than they

had been able to note.

It is a part of the scheme for this collection from the Gentleman's Magazine

to keep the reprinted articles as far as possible intact and unaltered. All

editorial additions are inserted between square brackets, and such notes as

are thought advisable, either for the elucidation of the text, or as showing

what has since been done, are placed at the end of the book. All the articles

are printed as they stand in the original, with the exception of those on

Signs of Inns. That portion of this series signed by “Hinyboro," and

originally printed in 1818-19, I have curtailed, because the author wandered

off into dissertations which, while entertaining of themselves, took up too

much space for their real value. Sometimes, when an article has not appeared

to me to be of sufficient importance to print in the text, I have either

printed it in extenso, or summarised it, iii the notes.

In the notes I do lay claim to have exhausted the references to any of the

subjects treated of. As a collection of materials for future use, it is not

necessary to add more to the original text than will be sufficient to correct

errors or supply such bibliographical or other information as will enable

readers to pursue the subject for themselves. To the more general text-books on

the subjects treated

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4325) (tudalen vii)

|

Preface.

vii

of I have but seldom i i . consult

the pages of Notes and Queries, i I . />' uf Archaic

Words, Nares' Glossary, \\ aJy.wGod's Oil J.-.H ^ii^ii j-'.fj'nt'ju'gy,

Skeat's Etymological Dictionary, for any additional facts they wish to

obtain. On the subject of Diaiect there are of course the valuable

publications of the English Dialect Society and some volumes issued by the

Philological Society to consult. On the subject of Proverbs I may refer to

Hazlitt's Collection of English Proverbs and Proverbial Phrases, re-issued in

a second edition in 1882; Bonn's English Proverbs and Polyglot of Proverbs.

On Names of Persons and Places, a subject long of interest to students and

scholars, the Rev. Isaac Taylor's Words and Places, R. C. Hope's Dialectal

Place Nomenclature^ Edmunds' Names of Places, Ferguson's River Names of

Europe, English Surnames, Teutonic Name System, and Surnames as a Science,

Leo's Rectitudines Singularum Persona-nun, Bardsley's English Surnames,

Bowditch's Suffolk Surnames, and Captain R. C. Temple's Proper Names of the

Panjabis, should be consulted. On the Signs of Inns Notes and Queries has

long devoted much attention, and there is Larwood and Hotten's History of

Signboards.

In travelling over such a vast quantity of printed matter it is possible I

may have missed some small items of interest, though every available

precaution against this has been taken. The following items are not included

in the volume because they are not of sufficient value to preserve in their

present form, though a reference to them here may be useful:

PROVERBS.

Sent to Coventry, 1791, Part II, pp. 622, 623. He that fights and runs away,

1835, Part L, pp. 338, 562.

WORD-LISTS.

Glossary to Sir Walter Scott's Sir Tristrem, 1833, Part II., p. 307; 1834,

Part L, pp. 167-170.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4326) (tudalen viii)

|

viii via Preface

A Persic Glossary of Mercantile Terns, 1769, pp. 391, 392. Origin of the term

Druid, 1833, Part I, p. 328. Use of the word Great, 177!) pp. 115, 116.

LANGUAGE.

Use of the articles A and AN, Vulgar corruptions, 1790, Part II., p. 617.

Petition of C. G. and J., 1758, pp. 79, So. Phrases borrowed from the Latin,

1783, Part I, p. 232. Remarks on the language of Biscay and Ireland, 1759,

pp. 378-380. Language of North and South Wales, 1769, p. 127; 1770, pp. 152,

210, 211, 292, 293.

NAMES.

Name of Mill, 1788, Part II., p. 1154.

On the origin of Proper Names, 1830, Part I., pp. 298-300.

It now remains to say a word or two about the contributors. With the

exception of M. Green and Paul Gemsage, or Gemsege, all are different from

those whose names appeared in the volume on Manners and Customs. Paul

Gemsage, as we already know, was Dr. Samuel Pegge, and besides this

anagramatic nom-de-plume we have him also appearing under the signature of T.

Row. There are a great many papers signed by only initials, or some still

less distinguishable a sign, and for the purpose of identifying these writers

I am very kindly promised some help by Dr. Brushfield, of Budleigh Salterton,

who fortunately possesses a copy of the Gentleman! s Magazine, once belonging

to Mr. Nichols, and which contains manuscript notes on all the authors. Of

the other names the most distinguished is that of John Mitchell Kemble, the

Anglo-Saxon scholar, well known as the author of Saxons in England, and

editor of the Codex Diplomaticus

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4327) (tudalen ix)

|

Preface.

ix

Saxonici. Mr. Kemble's books are known to all lovers of Saxon England, and

his memory is not yet lost to the students of this age. Talking some time ago

to Mr. Thorns, he told me of a visit he once made to Mr. Kemble at, I think,

Crouch End. Driving from the station to his residence, Mr. Kemble described

to his friend the historic value of the village green they passed on their

way, and pointed out the evidences of the mark system still extant. This

episode occurred before Saxons in England was published, and Mr. Thorns told

me he well remembered the fire and enthusiasm of his brilliant host. There are

only two other names of importance. Davies Gilbert was born in 1767 and died

in 1837. He was D.C.L., F.R.S., and F.S.A. In 1804 he was elected M.P. for

Helston, and in 1806 for Bodmin, for which town he sat till 1832. His real

name was Giddy, which he altered in 1817 to Gilbert. For three years he was

President of the Royal Society. Among his contributions to literature may be

mentioned Christmas Carols, 1823; Mount Calvary, written in Cornish and

interpreted in the English tongue by John Keignin, gent., in 1682, 1826;

Creation of the World, written in Cornish in 1611,1827; Parochial History of

Cornwall, 4 vols., 1837-8. Mr. John Trotter Brockett is well known as an

antiquary. He was an attorney at Carlisle, born 1788, died 1842. James Hall,

who writes in 1809 (see p. 73), was perhaps Sir James Hall, eminent for

geology and chemical science, but who wrote an Essay on the Origin,

Principles and History of Gothic Architecture, born 1761, died 1832, The

celebrated Dorset antiquary, the Rev. W. Barnes, contributed to this section

of the Gentleman 's Magazine. Mr. Barnes is still living at his rectory of

Winterbourne, to which he was instituted in 1862. Some of Mr. Barnes's

contributions to Dorset Dialect are enumerated in a note (p. 341). Another

living contributor is Mr. T. T. Wilkinson, the well-known Lancashire

antiquary, and joint author, with the late Mr. Harland, of Legends and

Traditions of Lancashire. The other names are D. A. Briton, J. Dowland, J.

Gordon, William

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4328) (tudalen x)

|

x Preface.

Humphries, T. Norworth, William A. Part, H. Philipps, John Wilson, Edward J.

Wood. The signatures J. Ray and James Howell in 1748 (pp. 70, 71) are no

doubt adaptations from those well-known authorities on proverbs, Ray having

lived 1627-1704 and Howell 1594-1666.

G. L. GOMME. CASTELNAU, BARNES, S.W. April, 1884.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4329) (tudalen xi)

|

xi

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4330) (tudalen xii)

|

xii CONTENTS.

PREFACE

LISTS OK LOCAL WORDS AND SPECIMENS OF DIALECT

Grose's Provincial Dialect ...

Provincial Glossaries

The North Country Dialect

Northumberland Dialect

Provincial Words from Newcastle

Local Words used in Northumberland

Vocabulary of the Lancashire Dialect

Spenser and the East Lancashire Dialect

A List of Local Expressions

Letters in the Dialect of the Shetland Islands

Glossary to the Zetland Dialect

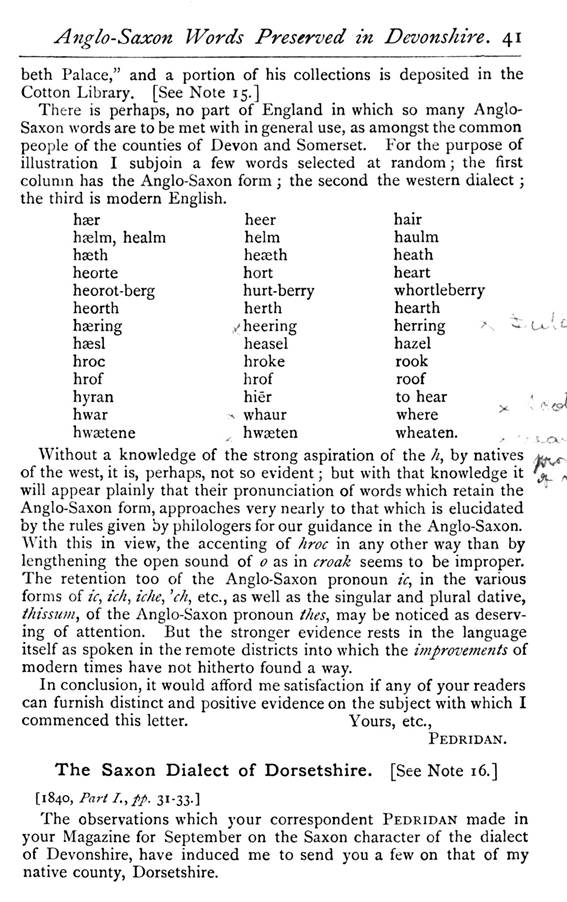

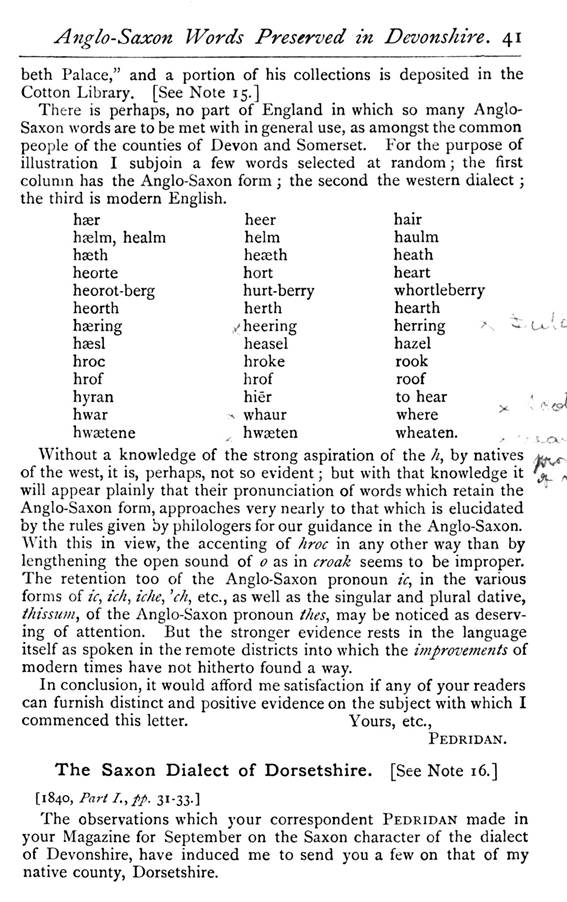

Anglo-Saxon Words preserved in Devonshire

Saxon Dialect of Dorsetshire

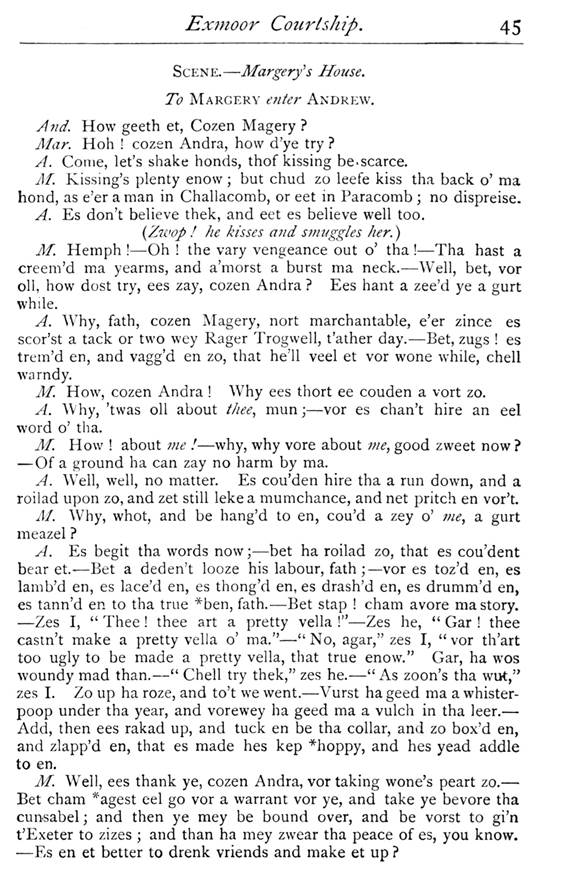

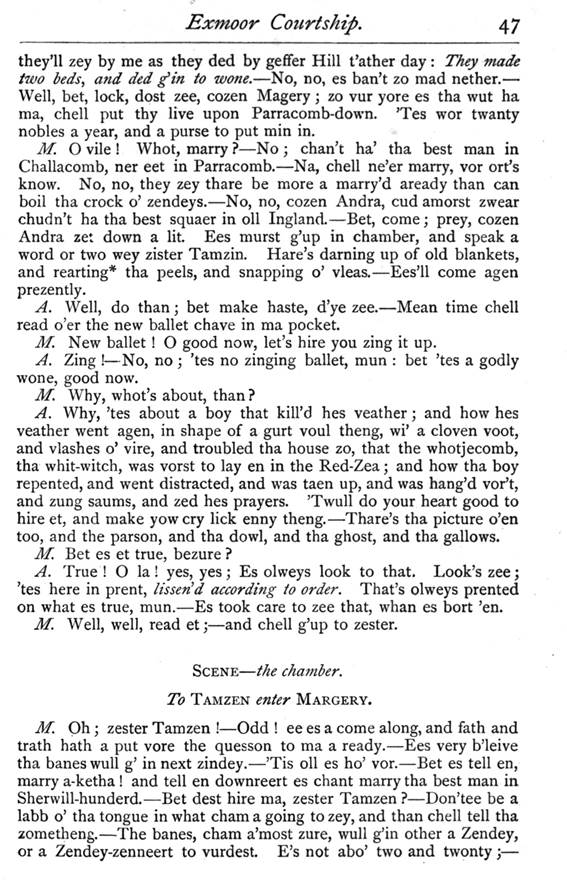

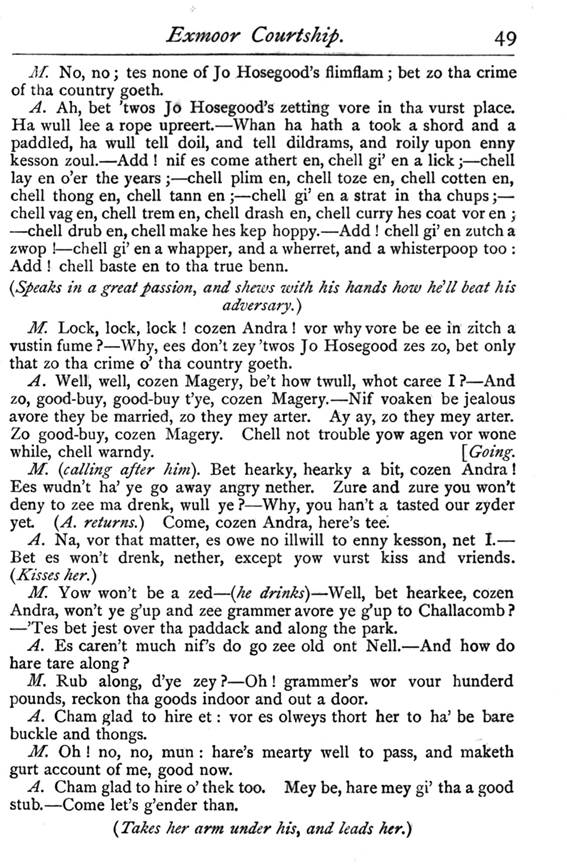

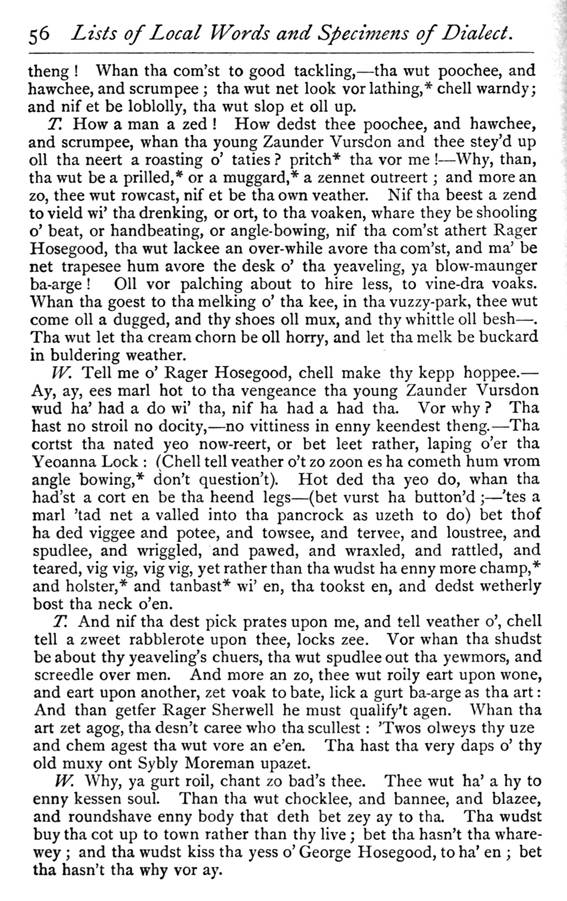

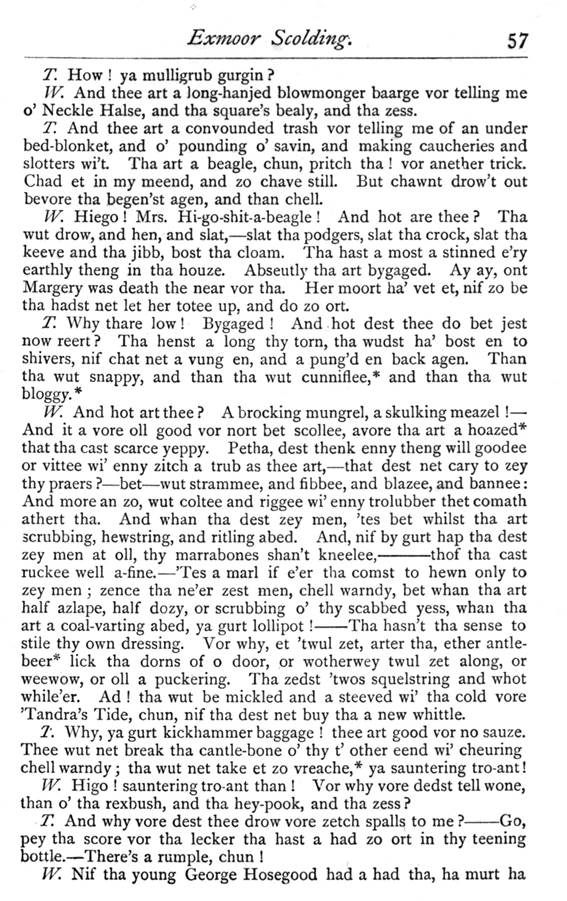

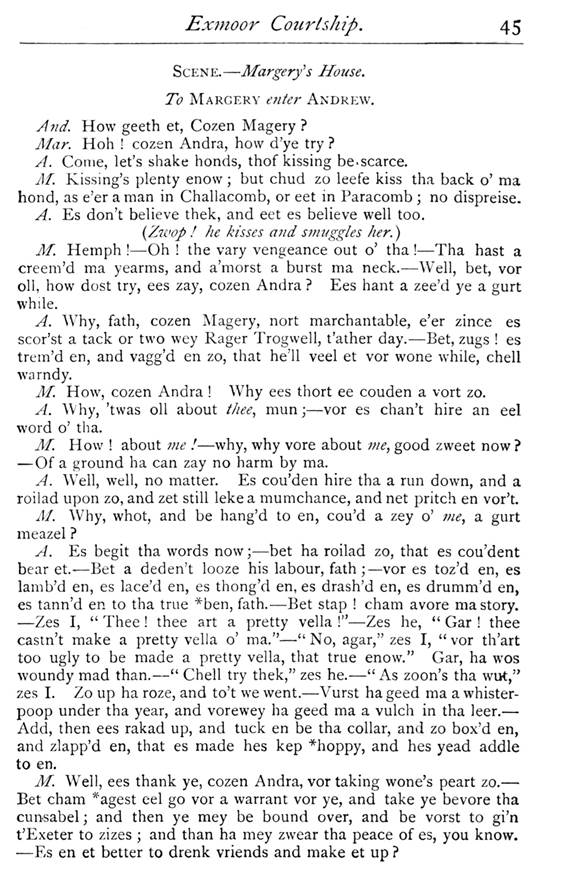

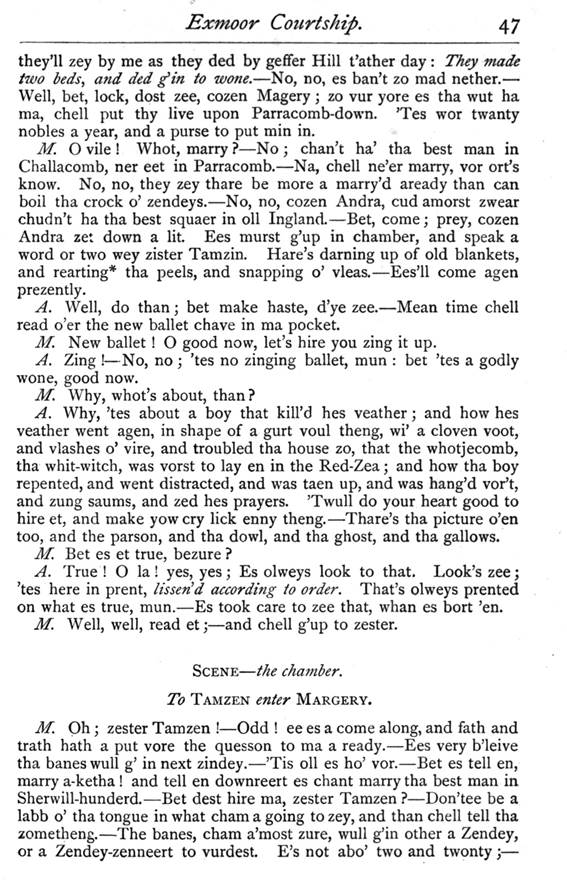

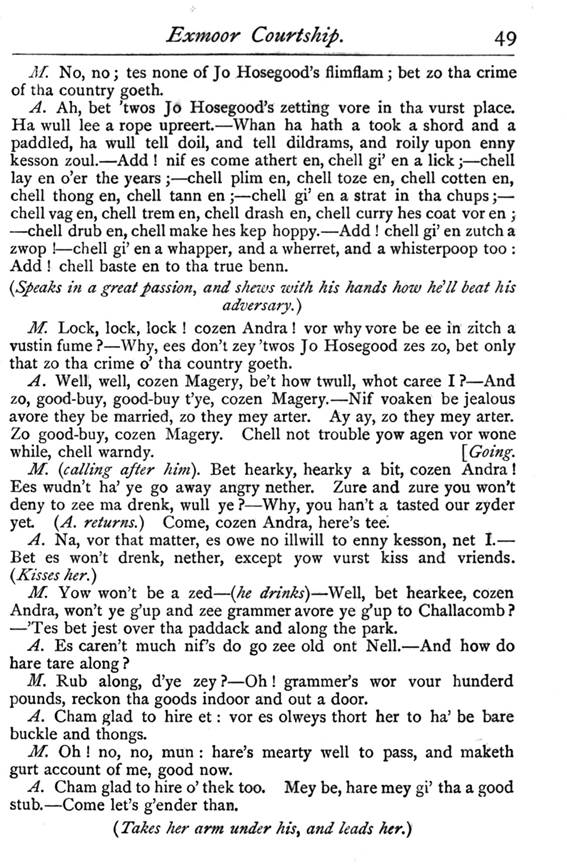

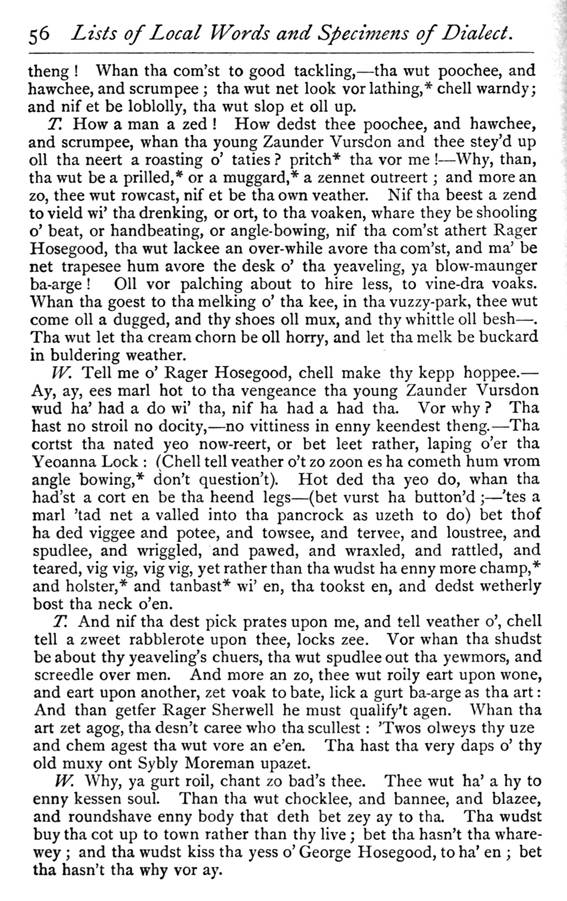

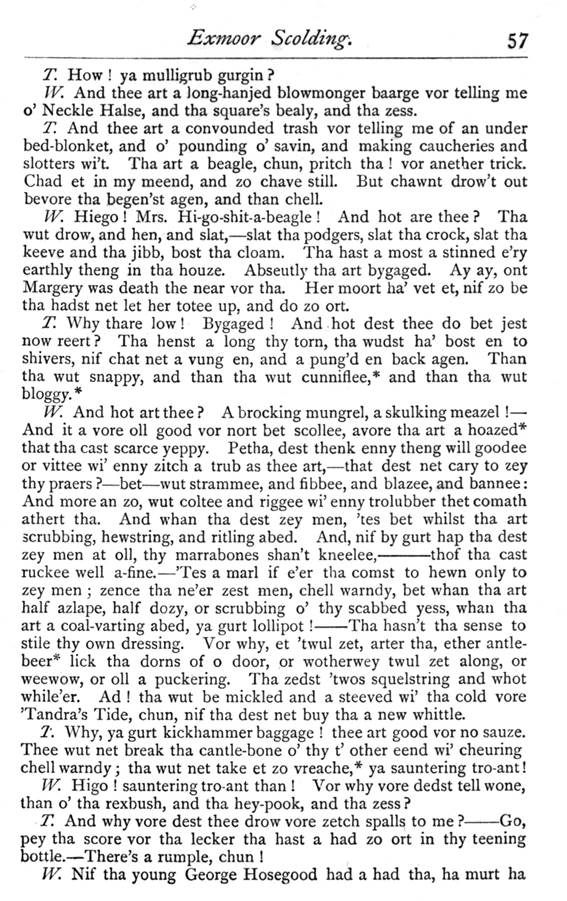

Exmoor Courtship

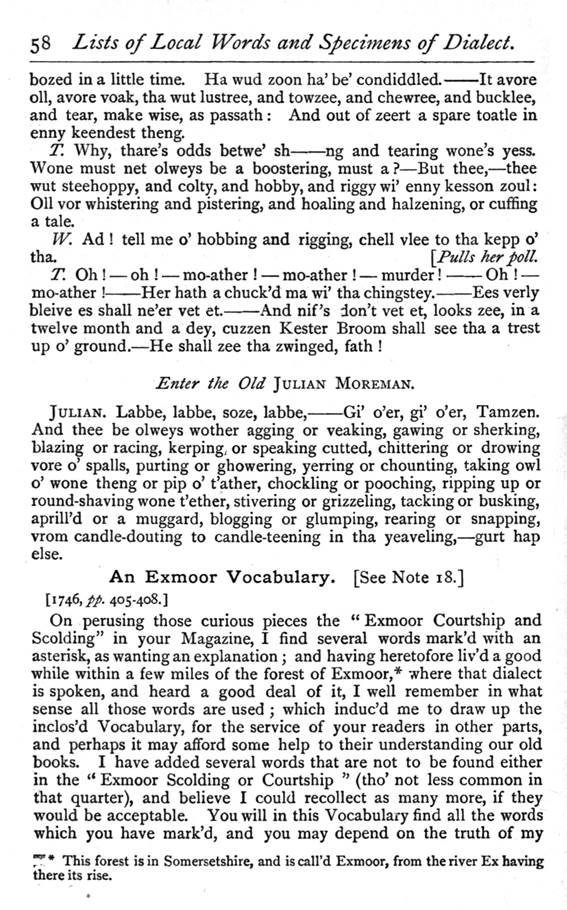

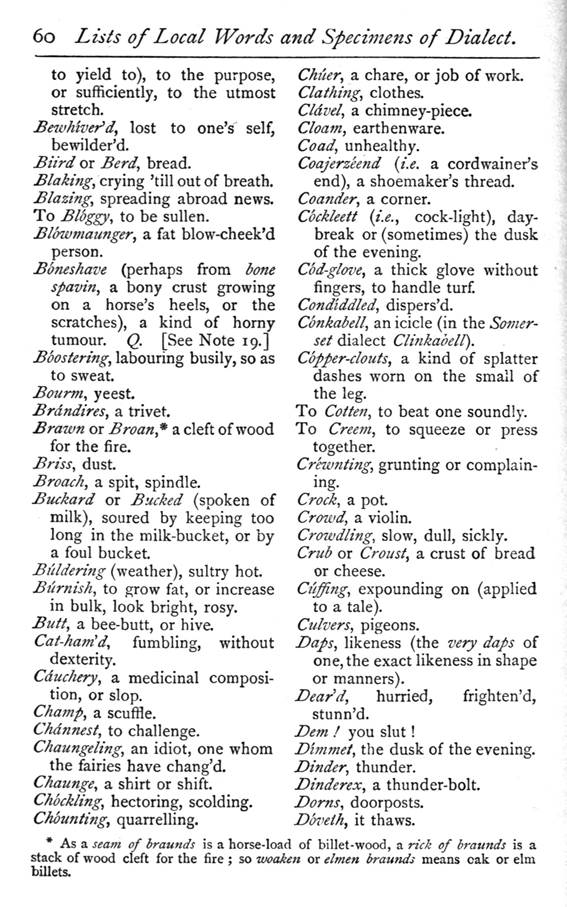

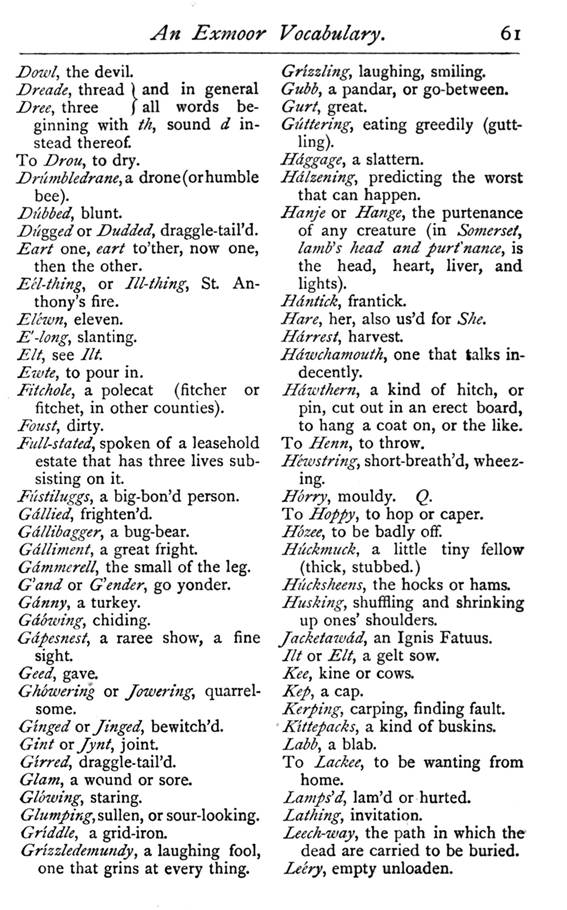

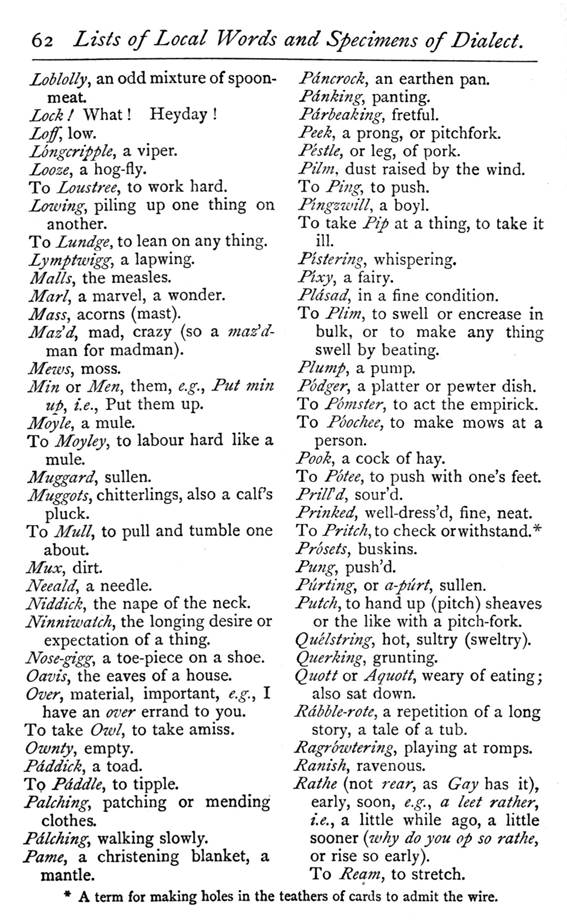

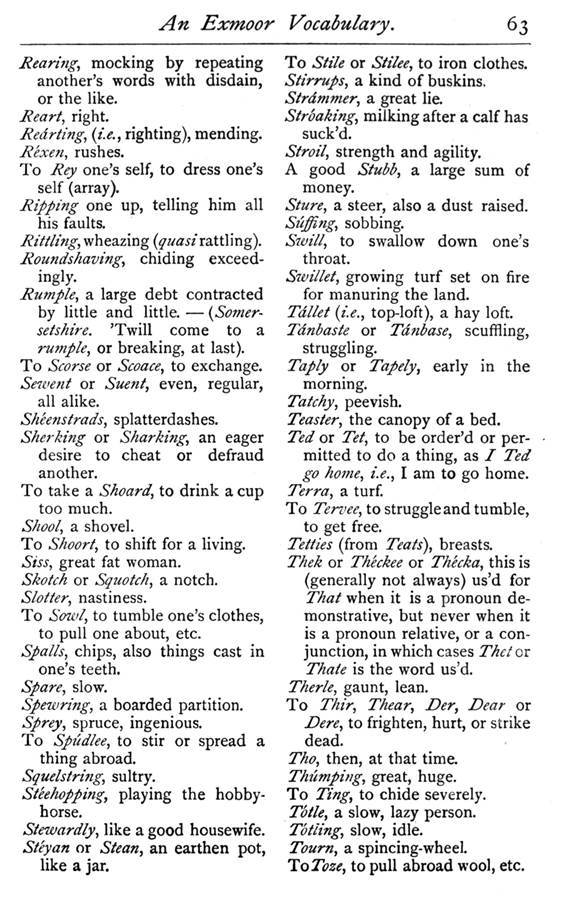

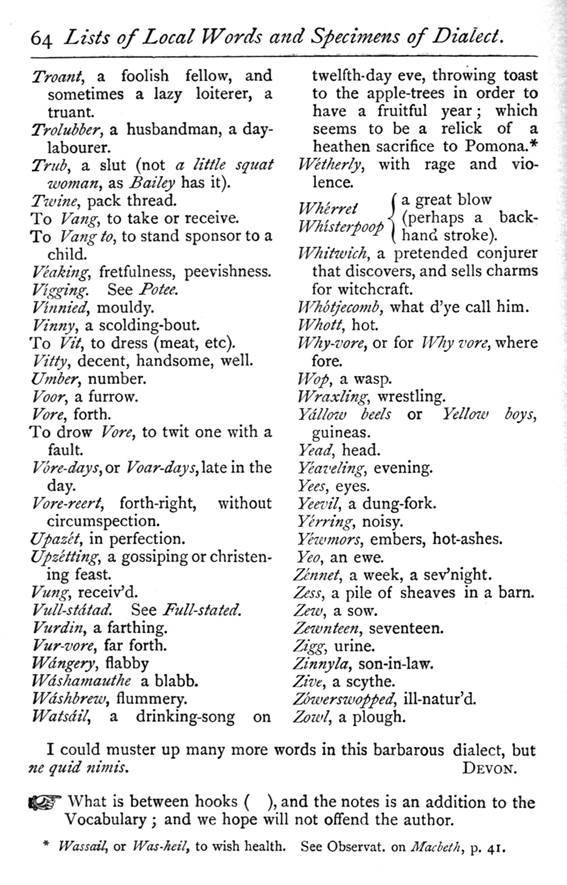

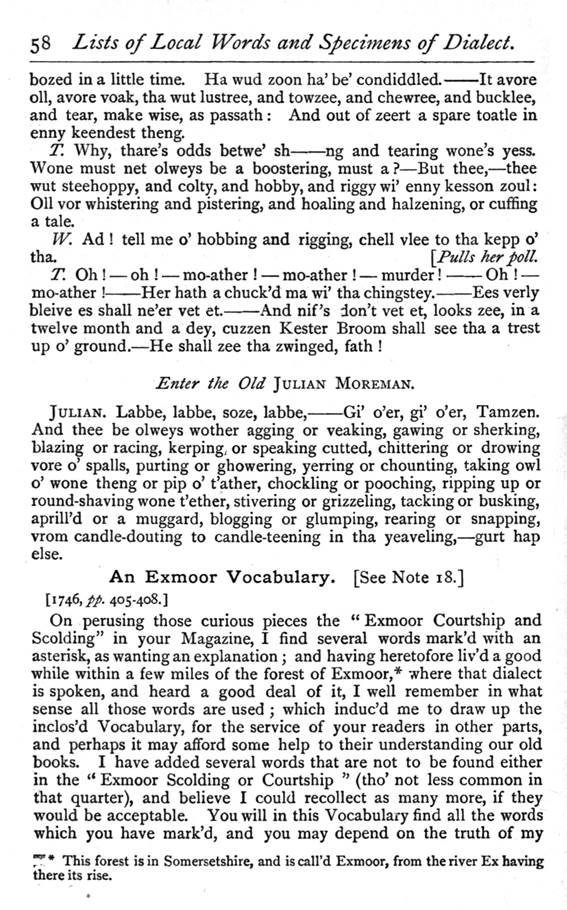

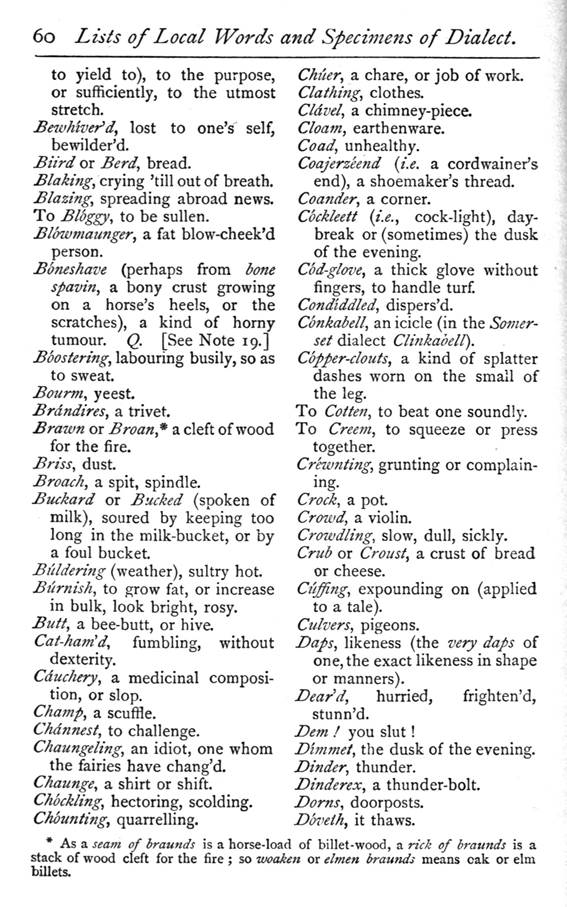

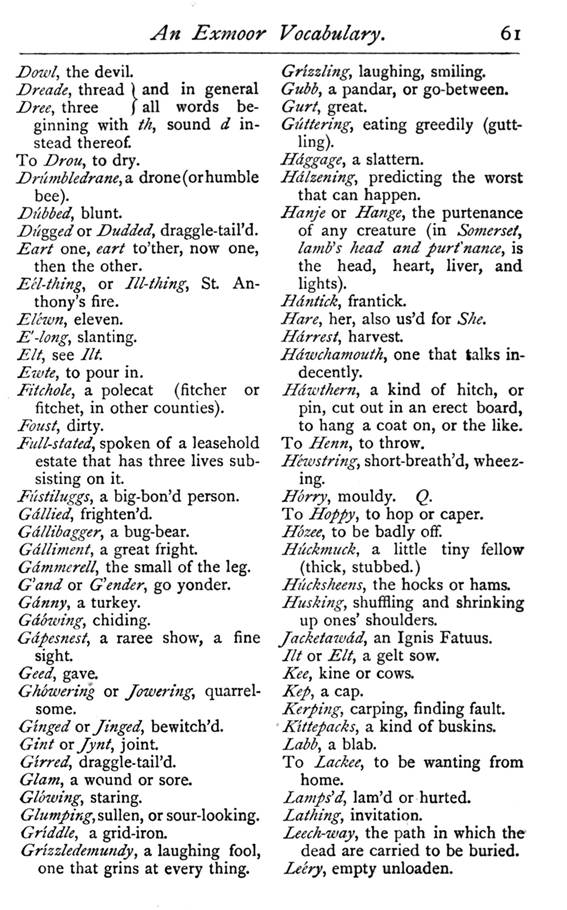

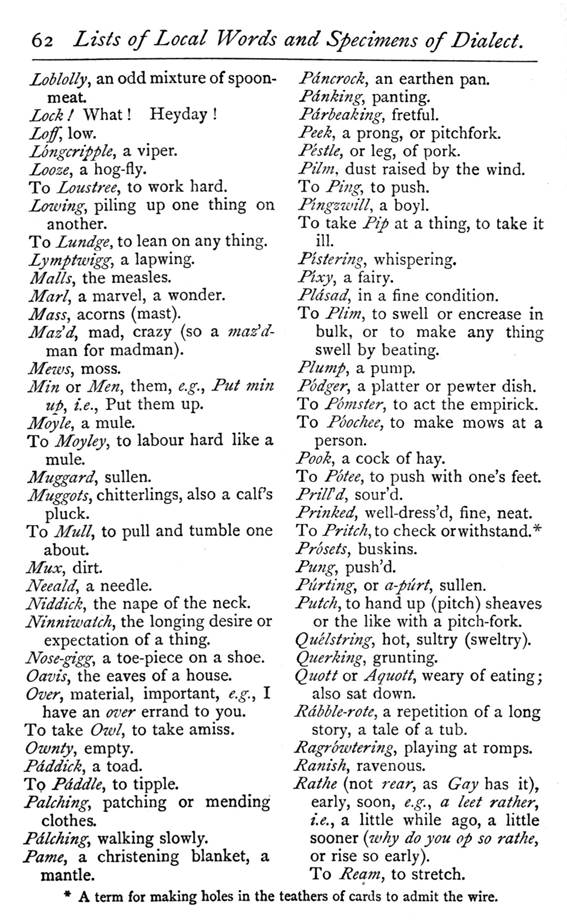

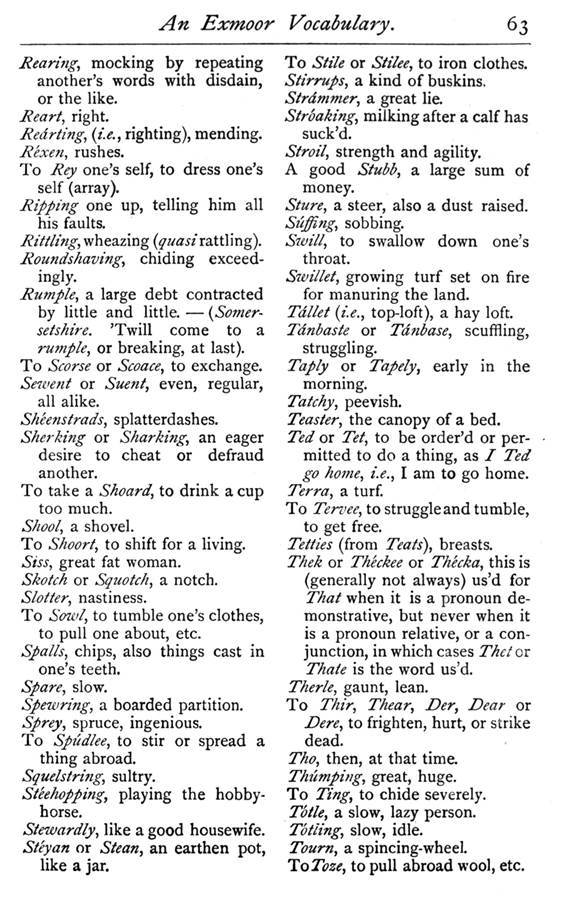

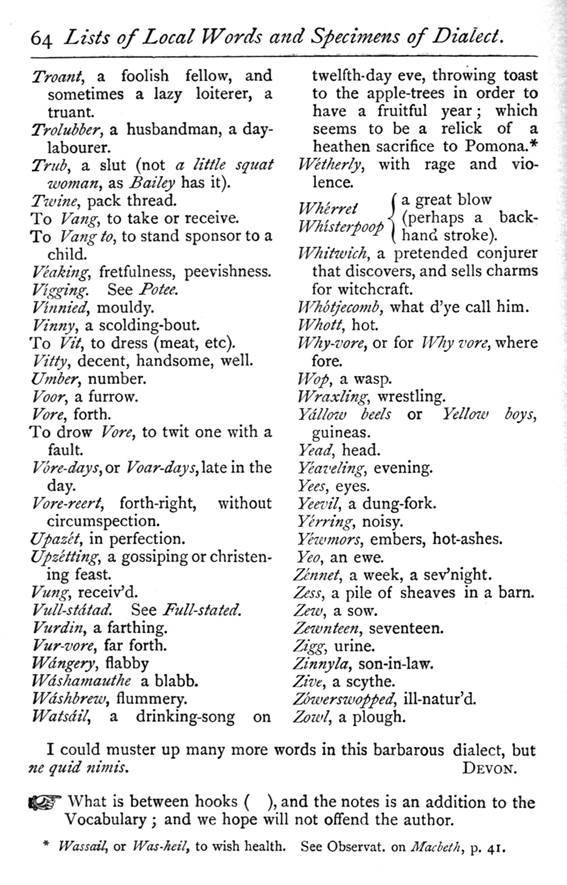

An Exmoor Vocabulary

Popular Names of Natural Objects PROVERBS:

Witty and Seasonable Proverbs

Anglo-Saxon Proverb

Greek Proverbs for Absurd Actions

English Proverb explained

An old Proverb illustrated from a Play in MS.

Soon Ripe soon Rotten .-

Cuckoo Proverb

PAGE V

13 15 17

21

24 28

37 39 4i 43 58 65

69

71

72

74 76 78 78

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4331) (tudalen xiii)

|

xiii

Contents.

PAGE

PROVERBS continued.

Weather Proverbs - 79

Local Proverb - .... So

Season Proverbs - So

Round about Revess - - - - 82

Northern Proverbs - - 83

A Peck of March Dust is worth a King's Ransom - 84

Lancashire Proverb - - - 86

PROVERBIAL PHRASES:

An't Please the Pigs - - 89

Bear the Bell - 90

Cat in the Pan - - 9

Cock's Stride - 101

Cunning as Crowd cr - - - 102

Dab at Anything - - 104

Drunk as David's Sow ... 105

Eyes draw Straws - - -105

Keeling the Pot - - 106

Month's mind to it - - - icg

Nine of Diamonds the Curse of Scotland - no

Old Maids leading Apes in Hell 112

Old Nick - -112

Ploughing with Dogs - 113

Running a Muck - - 114

Sixes and Sevens - - 117

Spick and Span - - 117

Thief in a Candle - - liS

Topsy-Turvy 119

Trelawny And shall Trelawny Die - - - - 119

U. P. K. spells Goslings - 120

Wake - - 121

Wine of one Ear - - - 121

As the Devil loves Apple Dumplings - - 122

Proverbial Rhyme - ... 122

SPECIAL WORDS:

Apple of the Eye - - - 125

Aroint - - - 125

Contents.

xiii

J-AGE

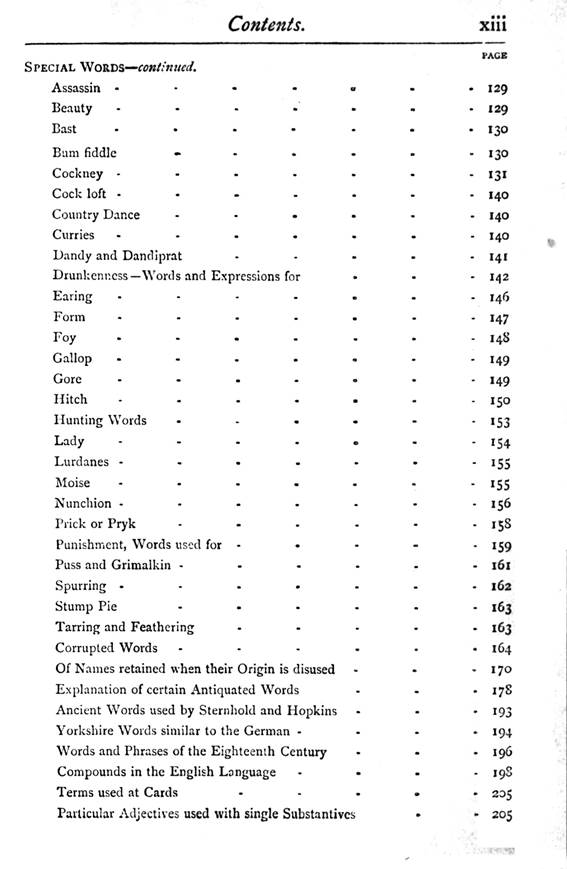

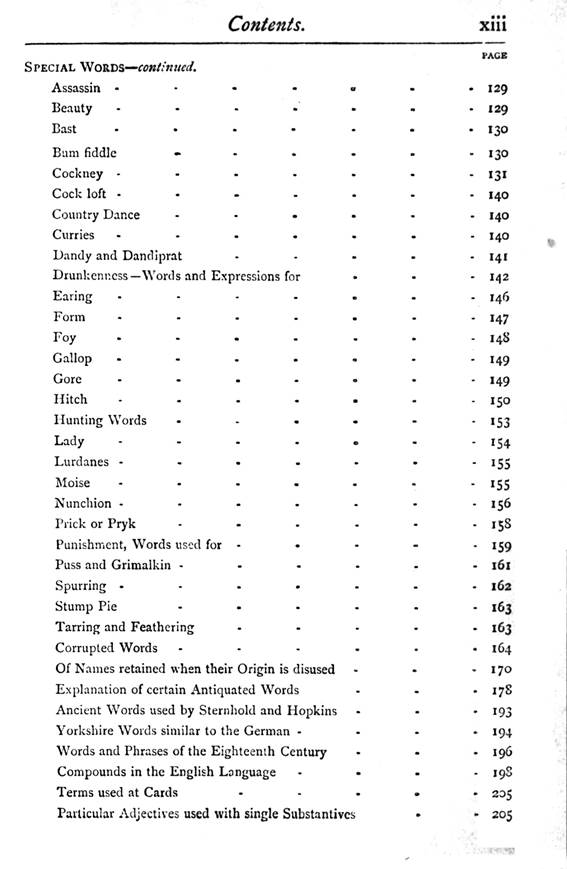

SPECIAL WORDS continued.

Assassin - - 129

Beauty - -129

Bast 130

Bam fiddle 130

Cockney - 131

Cock loft - .... - 140

Country Dance - - 140 Curries ..... 140

Dandy and Dandiprat - - - 141

Drunkenness Words and Expressions for - 142

Earing - . - 146 Form ....... 147

Foy > ... 148

Gallop ..... - 149

Gore .... 149

Hitch - 150

Hunting Words 153

Lady > 154

Lurdanes - . - 155

Moise ..... - 155

Nunchion - ... - 156

Prick or Pryk - 1 58

Punishment, Words used for - 159

Puss and Grimalkin - - - 161

Spurring ... 162

Stump Pie - 163

Tarring and Feathering - 163

Corrupted Words - 164

Of Names retained when their Origin is disused - 170 Explanation of certain

Antiquated Words ... 178

Ancient Words used by Sternhold and Hopkins - 193

Yorkshire Words similar to the German - - 194

Words and Phrases of the Eighteenth Century - - 196

Compounds in the English Language - 198 Terms used at Cards

Particular Adjectives used with single Substantives 205

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4332) (tudalen xiv)

|

xiv

Contents.

PAGB

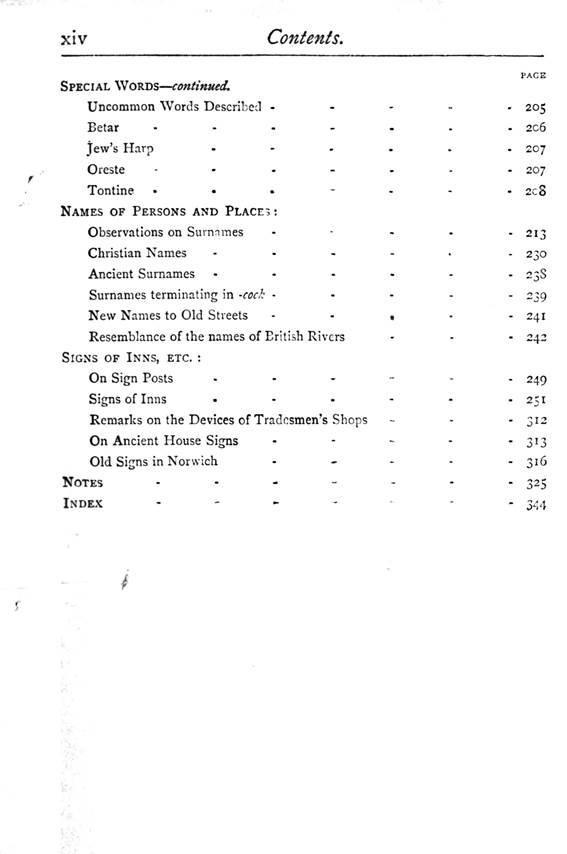

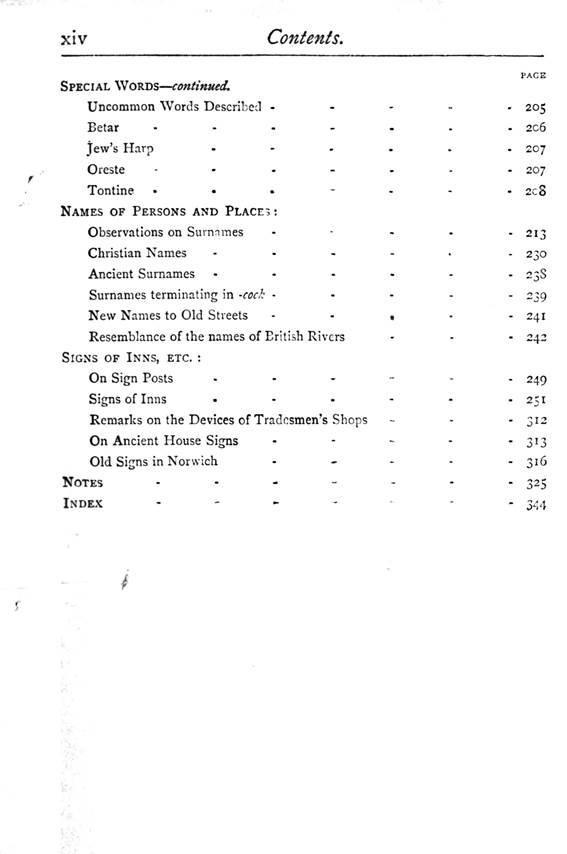

SPECIAL WORDS continued.

Uncommon Words Describee! - - 205

Betar ... ... 206

Jew's Harp - - - - . . 207

Oreste ... ... 207

Tontine ... ... 2 c8

NAMES OF PERSONS AND PLACES:

Observations on Surnnmes - - - 213

Christian Names ... . 230

Ancient Surnames .... . 238

Surnames terminating in -cock ... - 239

New Names to Old Streets - - 241

Resemblance of the names of British Rivers 242

SIGNS OF INNS, ETC.:

On Sign Posts ... . 249

Signs of Inns - - 251

Remarks on the Devices of Tradesmen's Shops - - 312

On Ancient House Signs - -313

Old Signs in Norwich - 316

NOTES - - 325

INDEX - - 344

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4333) (tudalen 002)

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4334) (tudalen 003)

|

3Lists of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

LISTS OF

LOCAL WORDS AND SPECIMENS OF DIALECT.

Grose's

“Provincial Glossary."

[1790, Part /., /. 26.]

TURNING over Capt. Grose's “Provincial Glossary “some time ago, and observing

it to be far from perfect, I have since occasionally amused myself with

setting down, as they occurred to me, some provincial terms and phrases,

which I found that gentleman had overlooked; and the district in which I am

mostly resident abounds so much with these peculiarities, that, if Mr. Grose

should ever think fit to give the world another edition of his

“Glossary," I believe I could furnish him with near two hundred

Somersetisms (and to these perhaps as many more might be added), which he has

not noticed. I am likewise inclined to think, that persons versed in the

dialect of other parts of the kingdom will find the number of their

provincial words equally deficient. I imagine, also, that with the help of

Saxon and French dictionaries (and perhaps a few other books) Mr. Grose might

have given the etymology of more words than he has at present done.

This is not meant as any disparagement of the ingenious Captain's

performance: he deserves much credit for the undertaking; and, all things

considered, he has succeeded very well; he has shewn himself in this, as in

the rest of his publications, no less a diligent and industrious antiquary,

than a pleasant and lively writer; but it is next to impossible for the first

attempt at a work of this kind to be anything like complete.

In his Preface, Mr. Grose justly observes, that “the utility of a Provincial

Glossary, to all persons desirous of understanding our ancient poets, is so

universally acknowledged, that to enter into a proof of it would be entirely

a work of supererogation." However, it would perhaps be an improvement

of his plan, to subjoin to the several words, of which any could be found,

examples of their being

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4335) (tudalen 004)

|

4 Lists of

Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

used by our elder authors, both poets and prose-writers. Shakspeare alone

will afford many such instances.

I fancy too, that the collection of “Local Proverbs," though certainly

superior to those of Fuller and Ray, might still be considerably enlarged. In

Somersetshire I have met with two, which have escaped him. One of them, being

illustrative of family history, I will here set down:

“Homer, Popharn, Wyndham, and Thynne, "When th' Abbot went out, then

they came in."

[See Note i.] D. L.

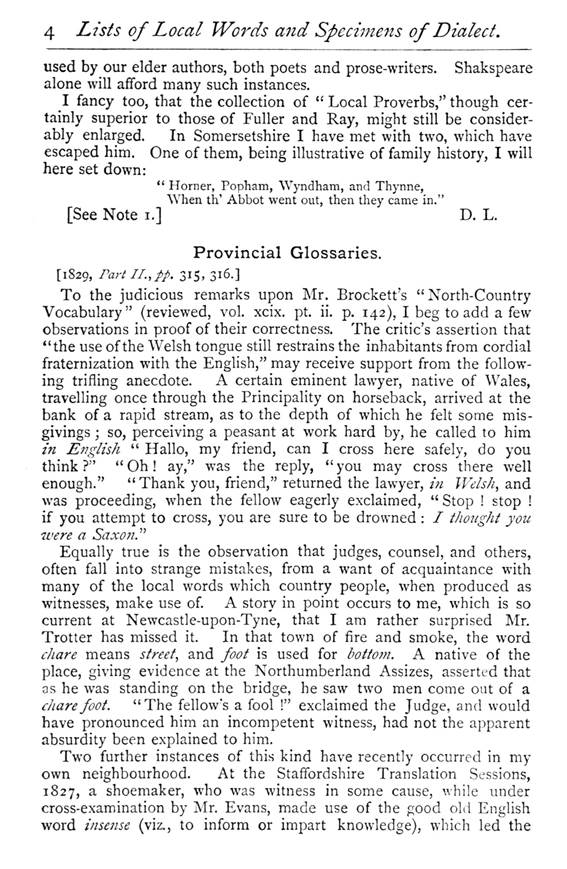

Provincial Glossaries.

[1829, Part II., pp. 315, 316.]

To the judicious remarks upon Mr. Brockett's "North-Country

Vocabulary" (reviewed, vol. xcix. pt. ii. p. 142), I beg to add a few

observations in proof of their correctness. The critic's assertion that

"the use of the Welsh tongue still restrains the inhabitants from

cordial fraternization with the English," may receive support from the

following trifling anecdote. A certain eminent lawyer, native of Wales,

travelling once through the Principality on horseback, arrived at the bank of

a rapid stream, as to the depth of which he felt some misgivings; so, perceiving

a peasant at work hard by, he called to him in English “Hallo, my friend, can

I cross here safely, do you think?" "Oh! ay," was the reply,

"you may cross there well enough." "Thank you, friend,"

returned the lawyer, in Welsh, and was proceeding, when the fellow eagerly

exclaimed, "Stop! stop! if you attempt to cross, you are sure to be

drowned: / thought you -were a Saxon."

Equally true is the observation that judges, counsel, and others, often fall

into strange mistakes, from a want of acquaintance with many of the local

words which country people, when produced as witnesses, make use of. A story

in point occurs to me, which is so current at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, that I am

rather surprised Mr. Trotter has missed it. In that town of fire and smoke,

the word chare means street, and foot is used for bottom. A native of the

place, giving evidence at the Northumberland Assizes, asserted that as he was

standing on the bridge, he saw two men come out of a chare foot. "The

fellow's a fool!" exclaimed the Judge, and would have pronounced him an

incompetent witness, had not the apparent absurdity been explained to him.

Two further instances of this kind have recently occurred in my own

neighbourhood. At the Staffordshire Translation Sessions, 1827, a shoemaker,

who was witness in some cause, while under cross-examination by Mr. Evans,

made use of the good old English word insense (viz., to inform or impart

knowledge), which led the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4336) (tudalen 005)

|

Provincial

Glossaries.

“learned

“counsel to be extremely witty at honest Crispin's expense. The shoemaker,

however, was justified, and the lawyer shewn his error, by a correspondent of

the Staffordshire Advertiser, who quoted the following and other passages

from Shakspeare, the meaning of which has been clean mistaken by the

commentators:

"I have

Insens'd the lords o* the council that he is A most arch heretic."

Henry VIII., Act v. Sc. I.

The lower classes in this part of the country often use the word

understanding to express the sense of hearing. At the Staffordshire Summer

Assizes, 1827, an elderly person applied to Mr. Baron Garrow to be excused

serving as a juryman, on the ground that he was “rather thick of understanding."

The learned judge, taking the expression in its London acceptation,

complimented him on his singular modesty, and said that he considered himself

bound to comply with a request founded on such a plea, though the applicant

had no doubt under-rated his powers of intellect.

As to what the reviewer says of the terms wench, maid, etc., I may observe

that among the common people in Staffordshire the words boy and girl seem

even now to be scarcely known, or at least are never used, lad and wench

being the universal substitutes. Young women also are called wenches, without

any offensive meaning, though in many parts, and especially in the

metropolis, the appellation has become one of vulgar contempt Hence I have

heard that line in Othello,

“O ill-starr'd wench, pale as thy smock!"

thus softened down to suit the fastidious ears of a London audience,

“O ill-starr'd wretch, pale as thy sheets /"

Shakspeare, with all the writers of his age, used the term wench in its

pristine acceptation of young woman; and it occurs in this sense in 2nd

Samuel, chap. xvii. ver. 1 7; but that it had sometimes a derogatory meaning,

or was rarely applied to the higher classes, may be gathered from a line in

the “Canterbury Tales":

“I am a gentil woman, and no wench."

Merchant's Tale, 10076.

See also the “Manciple's Tale," ver. 17169, Tyrwhitt's edit.

To shew that maid* once meant simply a young woman, chaste or unchaste as the

case might be, numberless proofs could be adduced; but modern usage seems to

have so restricted the sense of the word, that it is now held to be

synonymous with virgin intacta puella; and much dull pleasantry has been

expended upon those writers who have ventured to use it in its original

signification. Among others,

* Bailey thus explains the word: “A Woman, also a GirL A scornful name for a

girl or maid. A crack or w e."

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4337) (tudalen 006)

|

6 Lists of

Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

Mr. T. Dibdin, one of whose songs in the opera of the “Cabinet," has

this passage:

"His wish obtain'd the lover blest, Then left the maid to die."

Mr. T. Moore, also, has been charged by ignoramuses with committing a bull,

because in the well-known ditty, commencing “You remember Ellen," after

saying that “William had made her his bride," he adds in a line or two

below, “Not much was the maiden's heart at ease!" So easy is it for

small wits to be mighty smart in their own conceit, upon matters which they

do not understand.

At what period the word began to be confined to its present limited

signification, I cannot precisely determine, but it probably was subsequent

to the appearance of Pope's “Iliad," since in the ist, Briseis is termed

a maid, after she has been torn from the arms of Agamemnon, and the

probability mentioned that in her old age she may be “doom'd to deck the bed

she once enjoy'd." [Bk. i. line 44.] Leaving the point to be determined

by more skilful linguists, I shall close this gossiping paper with two or

three passages from old writers of various dates, shewing beyond dispute that

to whatever meaning the word may now be restricted, its signification was

once as comprehensive as I have asserted. In the comedy called “How a Man may

choose a Good Wife from a Bad," 1602, Mistress Arthur says:

“O father, be more patient; if you wrong My honest husband, all the blame be

mine, Because you do it only for my sake: I am his handmaid"

In Ravenscroft's "Titus Andronicus," 1687, after Lavinia's husband has

been murdered, Demetrius seizes her, and exclaims:

"Now further off let's bear this trembling maid"

But perhaps a more apt instance could not possibly be adduced, than the

following passage from Whetstone's “Promos and Cassandra," 1578:

“Enter Polina, the mayde that Andrugio lov'd.

“Polina curst, what dame alyve Hath cause of griefe lyke thee, "NVho

(wonne by love) hath yeeld tlie spoyle Of thy virginity?"

The North-Country Dialect.

[1836, Part I., pp. 499, 500.]

Yorkshire has at last found a champion to rescue her emphatic dialect from

disrepute, and every North Riding man must feel himself raised in the scale

of civilized talkers, when he reads the amusing paper on English Dialects in

the last Number of the Quarterly. [See

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4338) (tudalen 007)

|

The

North-Coimtry Dialect.

Note 2.]

There are several curious notices of the modes of conjugating verbs in the

northern districts; but on one point, the imperative plural, the writer does

not appear fully informed. He gives Chaucer's dialogue between the Yorkshire

Scholars and the Miller of Trampington, from an uncollated MS.: one of the

clerks is made to say,

“I pray you spedes us liethen that ye may;"

and on the fourth word the Reviewer remarks, “apparently a lapsus calami for

spede" This, however, is a correct North-country form of the imperative

plural. The Northumbrian gloss on the Durham Gospels, Mark i. v. 3, gives the

warning of John the Baptist, “Gearuas Drihtnes woeg;" the common A.S.

version is “Gegearwiath Drihtnes weg." At v. 15, our Saviour says,

“Hreowiges and gelefes to th' godspell;" in the A.S. “Doth daedbote and

gelyfath tham godspelle." The religious antiquary will not fail to

observe the difference between the heart-repentance inculcated by the

Northern version, and the external religion substituted for it by the

Southern.

To cite a more modern authority: in the “Towneley Mystery, or Miracle Play,

of the Adoration of the Shepherds," Mak the Sheepstealers, endeavours,

when first introduced, to pass himself off as a Southern yeoman, and in his

assumed character addresses the Shepherds in the Southern imperative,

“Fyon you, goythe hence, Out of my presence, I must have reverence."

But after he finds himself recognised by them, he reverts to his mother

tongue, and calmly says,

Good, spekes soft

Over a

seeke woman's heede;"

and presses his hospitality on them with “Sirs, drynkes" Then we have

King Herod, the favourite hero of the miracle plays, dismissing his military

attendants to make way for the juris-consults.

11 Coys hence,

I have matters to melle With my prevey counselle."

And after the slaughter of the Innocents, he concludes with a piece of

characteristic advice to the audience:

“Sirs, this is my counselle, Bese not too cruelle."

The “Towneley Mysteries “are now in the press, and will shortly be published

under the auspices of the Surtees Society [see Note 3], accompanied by a preface

from the pen of a gentleman well acquainted

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4339) (tudalen 008)

|

8 Lists of

Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

with the topography of the north of England. The language appears, according

to the Reviewer's nomenclature, to be a mixture of the Northumbrian and

North- Anglian dialects, though the latter is, perhaps, most apparent in the

speeches of the low-lived characters, such as Cain and his ploughboy.

Yours, etc., J. GORDON.

Northumberland Dialect. [See Note 4.] [1836, Part /., pp. 606-608.]

In an article on Provincial Dialects ( Quarterly Review, No. no), an extract

from Wageby's “Skyll-Kay of Knawinge "* is given as a sample of the

Northumbrian dialect. When the article was written, I only knew the poem from

the account and the specimens furnished by Mr. [W. J.] Walker; and though I

had reason to think that the worthy monk of Fountains Abbey was greatly

indebted to Hampole's “Pricke of Conscience," I had not then the means

of verifying my suspicions. Having since had an opportunity of inspecting two

MSS. of the latter poem, preserved in the library of Lichfield Cathedral, I

am enabled to state that the “Skyll-Kay of Knawynge," is nothing more than

a Northumbrian rifacciamento of Hampole's poem, curtailed and interpolated ad

libitum, but still the same work in substance. This process appears to have

been carried on pretty extensively in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries,

insomuch that we are never sure of having a poem of that period in its

original form, unless we are so fortunate as to possess the author's

autograph.

It has occurred to me that the knowledge of this circumstance may help to

illustrate a point at present involved in a good deal of uncertainty. It

appears that the transcribers of those works not only interpolated them with

fresh matter, but in many instances accommodated them to their own dialect.

As the “Pricke of Conscience “ is one of our most common MSS., a comparison

of many different copies, especially when the date and place of transcription

can be ascertained, may greatly enlarge our knowledge of the limits and

distinguishing characteristics of the provincial dialects of this country, as

they existed in the fourteenth and following centuries. I shall therefore

give a brief account of the copies which have come under my notice, and shall

feel obliged to any of your readers who will communicate such information as

they possess on the subject.

I have no data for fixing the precise age of the two Lichfield MSS.; I

conjecture the older to be of the beginning of the fifteenth century; the

other, forty or fifty years later. The one which I call, for the

* “An account of a manuscript of ancient English poetry, entitled ' Clavis

Scientiae, or Bretayne's Skyll-Kay of Knawing,' by John de Wageby, Monk of

Fountains Abbey." 8vo., Lond., 1816, pp. 17 (only 50 copies printed).

[See Note 5.]

Northumberland

Dialect.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4340) (tudalen 009)

|

sake of

distinction, MS. A. is in the form of a small quarto, and consists at present

of 109 folios, the concluding one having been cut out. It is on vellum, in a

small but distinct character, with few contractions, and rubricated titles

and initials. The second, or MS. ., is bound up together with some tracks of

St. Anselm, and occupies 155 leaves. It is elaborately written, in a large

bold hand, greatly resembling the black letter of our early typographers, and

appears to be perfect. No author's name is given in either; but in the

peroration of both we are told

“Prickke of conscience yis* bok is i-hote."

I subjoin an extract from each, which your readers may compare with the

corresponding passage given by Warton from the Ashmole MS. with which, as Mr.

Price observes, the Lansdowne substantially agrees:

MS. A. Fol. 2:

For of alle yat god made bothe more and lesse

Man is most pryncipal and schal alle othre passe;

As zet schul here afterward sone,

Yat al yat he made wes for man a lone.

God to mannys kynde adde gret delyt,

Qwan he ordenyt for mannys profyt,

Hevene and erthe and al ye word a brod,

And al other thyng, and man to laste ende a bod,

And hym in his liknesse in cely stature,

As hym yat was most worthy creature,

Over alle other bestes qweche haven kynde,

And zaf hem wyth resoun and mende,

Evere for to knowyn boye god and ille,

And yar to god zaf hem with yat wille,

Bothen for to chese and for to holde

Good or evel, qweder yey wolde.

And also god ordenyt man for to dwelle

And for [to] leve in erthe, in flesch and felle,

And for to knowe hese werkys and hym to honoure,

And hese hestes for to kepen in everyche owre,

And if he to god buxum be come,

To ye blisse of hevene he schal be nome.

MS. B. fol. 2:

[JMannes kynde is to folowe godes wylle, And hys comandementes to fulfylle.]

* The character y, in this and similar cases, is to be considered as

equivalent to the Saxon h, th.

f The letter z represents the Saxon j. J Omitted in MS. A.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4341) (tudalen 010)

|

io Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

For of alle y l god made eyer mor or lasse, Man most woryy creature ysse. All

y l he made was for man y-done, As ze schal here aftur warde sone. God to

mannes kynde hath grete love, Whan he ordynede to mannes by hove Hevene and

erthe and all the worlde brode, And, of alle thynges, man laste he made To

hys lyknes [in] semely stature; And made hym most worthy creature Of other

creatures of alle kynde, And zaf hym w l skyle and mynde. For to knowe both

gowd and evelle, And ther w l he zaf hyme a fre wylle. For to chese and for

to holde Goude other evelle, wether he wolde. And also he ordynede man to

dwelle And lyve in erthe, bothe w 1 flech and felle, And knowe his werkys and

hym werchepe, And his comandementes to kepe; And zyfe he be to hym goud and

boxome, To endeles blysse atte laste to come.

On comparing the above with each other and with the passage given by Warton,

it will appear that the Lichfield MS. A. exhibits the most ancient text. The

poetry is more rude and inartificial, and the orthography and diction more

antiquated. In B. the lines are frequently recast, and the archaisms replaced

by more familiar expressions. There is also a considerable number of

interpolations, amounting in some instances to twenty lines in the hundred,

or a full fifth part. The Ashmole MS. appears to correspond with B. line for

line in substance, but differs materially in expression, and is evidently the

most modern of the three.

There is internal evidence that the text of B. was formed from that of A., or

one greatly resembling it. A portion of the former (fol. 83 to 92) is

transcribed in a different hand, and in an orthography approximating to that

of the latter. Qwat, qweche, qware: qwanne are employed instead of what,

whuche, etc.; en, or the somewhat uncommon form //, is substituted for the

usual plural in th: e. gr. 3rd pers. pi. shullen, or shuln, havit, dwellit, dredit,

etc. The phraseology also more closely resembles that of A.; in short, all

this portion appears to have been copied by one less ambitious of improving

upon his original, than his fellow-transcriber.

Warton observes that the Bodleian MSS. exhibit an older text than the

Ashmolean. The extracts which he gives agree pretty closely with the

corresponding passages in A.; the discrepancies being chiefly

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4342) (tudalen 011)

|

Northumberland

Dialect. 1 1

dialectical and orthographical. To place the matter in a clearer light, I

subjoin a tetraplar version of the description of the heavenly Jerusalem.

Bodleian text, ap. Warton:

This citie is y-set on an hei hille,

That no synful man may therto tille;

The whuche ich likne to beril clene,

Ac so fayr berel may non be y-sene.

Thulke hyl is nougt elles to understondynge,

But holi thugt and desyr brennynge,

The whuche holi men hadde heer to that place,

Whiles hi hadde on eorthe here lyves space;

And i likne, as y-may ymagene in my thougt,

The walles of hevene to walles that were y-wrougt

Of all maner preciouse stones, y-set y-fere,

And y-semented with gold brigt and clere;

Bot so brigt gold ne non so clene

Was in this worlde never y-sene. Lichfield MS. A. fol. 107-8:

This cete is set on an hey hille,

Yat no synful man may cum yer tille;

The qweche i likned to berel clene,

But so fayr berel may non be sene.

Yat hil is not else to understonge, (sic)

But holy yout and desyr brennynge,

Ye queche holy men han her had to yt place,

Whyl yei haddyn on erde here lytel space,

And i likne as i may ymagen in my thout,

Ye walls of hevene to the walls that weryn wrougt

Of all maner precyous stonys set in fere,

And symentid with gold bryt and clere;

But so bryt gold ne non so clene

In all this werd is no qwer sene. MS. B. fol. 1 86:

Yis cyte is yset on an hye hulle,

Yt no synful man may yerto telle;

Ye wuch I lykne to beryl clene,

And so fayr beral may non be sene.

Yulke hulle ys nouzt elles to understonde (sic)

Bote holy youzt and desyr brennyng.

Ye wuch holy men hadde her to y* place

Whyles hy hadde on erth here lyve space.

And I lykene as I ymagyne in my thouzt

Ye walles of hevene y l (sic) to walles y l were y-wrouzt

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4343) (tudalen 012)

|

12 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

Of alle manere precyous stones yset yfere, And ysemented wt gold bryzt and

clere; Bot so bryzt gold ne non so clene Was never in ys wordle [sic] ysene.

John de Wageby, ap. Walker:

This cyte es sett on swa heghe a hyll, That na synfull man may wynne

thartill; Swa clene here was never seen to syght, The whylk sail seme all of

beryl bryghL That hyll may be, to my understandyng, Holy thoght and byrnande

yhernyng, That haly men. hade to that stede, While they luffed here by, for

thar dede. All the walles are of stanes sere, Sementyde with gold bryght and

clere; Bot swa bryght gold and swa clene Was never nane in this werlde sene.

The language of the last extract seems to be of the fifteenth century: its

decided Northern character needs not to be pointed out more particularly. Of

the others, it may be observed that Warton's Bodleian MSS. and Lichfield MS.

B. strongly resemble each other in orthography and dialectical forms. Both

exhibit something of a Western character; though less strongly marked than

Robert of Gloucester. The Lansdowne text is evidently modernised, but still

preserves traces of a Mercian origin.

The Lichfield MS. A. differs considerably in verbal forms from the others,

though it exhibits substantially the same text as the Bodleian copies. The

infinitives and plurals in en, may be regarded as Mercian; in other respects

it appears to be tinctured with Middle Anglian. I conceive it might be

written in Derbyshire or West Leicestershire; but I would not undertake to

pronounce positively respecting this matter without further evidence than I

can at present command.

Yours, etc., EBORACENSIS.

P.S. I beg to thank Mr. Gordon (p. 499) for his valuable remarks on the

ancient Northumbrian form of the imperative plural in es. I had observed its

occurence in Havelok; but at that time supposed it to belong to the Midland

dialect. I have since met with several examples of its use in Northumbrian

compositions of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and have not the

least doubt of its being a genuine form. All who take an interest in this

branch of our literature will be rejoiced to see the Towneley Mysteries. For

my part, I

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4344) (tudalen 013)

|

Provincial

Words from Newcastle. 13

am fully convinced that neither the grammar nor the etymology of our language

will be thoroughly understood till all existing monuments of this class have

been carefully analysed.

Provincial

Words from Newcastle.

[1794, Part I., pp. 13, 14.]

Some years ago, when the plan of Mr. Croft's Dictionary was laid before the

public in your magazine [see Note 6], I thought it might be enriched with

many unpublished words which are in daily circulation in the town where I was

born. At that time I began a vocabulary, which I now send you, and have no

doubt but that I could have made considerable additions to it if I had been

still resident at Newcastle-uponTyne. The peculiar pronunciation of that

place is said to have been derived from the Danes, who settled there before

the Conquest. That the natives of Northumberland, in many of their words, and

in the method of pronouncing them, bear a strong resemblance to the present

natives of Denmark and Norway, needs no other argument but comparison.

Professor Thorkelin, of Copenhagen, has given a vocabulary of words common to

the Scotch, Icelanders, and Danes.* From these I have selected such as are

common also to the natives of Newcastle, and added them to my own list.

Though I send the words, I do not pretend to point out their derivation; but

apprehend that they will all, or the greater part of them, be found in the

ancient Saxon, or in the languages of the present Northern kingdoms.

Professor Thorkelin's words are marked in the following list with a star.

Cranks, two or more rows of iron crooks in a frame, used as a toaster.

Pant, a fountain.

Chare, a narrow street or alley.

Prog, to prick.

Clarty, wet, slippery, and dirty.

Clag, to stick.

Yetlin, a small iron pan with a bow handle and three feet.

Grozer, a gooseberry.

Girdle, a round iron plate with a bow handle, for baking.

Click, to catch hold of.

Canny, an epithet of approbation.

Caller, fresh and cool.

Vennel, a kennel or watercourse.

Snech, a latch to a door.

- f See [A.] Swinton's Travels [into Norway, Denmark, and Russia in the years

1788-1791. London: 1792: see Appendix, pp. 497-506.].

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4345) (tudalen 014)

|

14 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

Mun, Sir! probably for, Man! Cracker, a small baking dish, Smasher, a small

raised fruit pie. Spelk, a splinter of wood. Dean, a dale or valley.

Weeze, a wisp of straw or soft wool to put under a weight on the head.

Skeel, a wooden pail.

Grime, black, sooty.

Dother, to tremble.

Staith, a storehouse for coals where ships are loaded.

Keel, a coal-barge or boat.

Puy, a pole to push forward a keel.

Swape, a long oar instead of a rudder to a keel.

Lum, chimney of a cottage.

Lum-sweepers, chimney-sweepers.

Father, a cart of coals, containing bushels.

Waits, a band of musicians.

Houglur, the public whipper, etc., of criminals.

Beatment, a measure.

Kenting, ditto.

Corf, a wicker basket for coals at the colliery.

Marrow, a companion.

Cou'p, to overturn, to exchange.

Smash, to break in pieces.

Stramp, to tread or stamp upon.

A gad, a fishing-rod.

Sweel, when the tallow of a candle runs.

Swill, a round wicker basket.

Broach, a breast-buckle, spire of a church.

* Bairn, barn, a child.

*Bawk, balk, a beam.

*Bit, little; Dan. bitte smaa; Phrase, a little bit.

Bicker, a tumbler glass.

*Becker, a wooden dish.

* Blather, bladder.

*Burn, a rivulet.

*Fell, a more, gateshead fell.

* 'Flicker, flitter, to vibrate like the wings of small birds.

*Fur, a furrow, rig and fur.

*Gar, Iceland. Germ, to force one to do any thing.

* Gimmes, an ewe from one to two years old.

Hag, a mist.

*Hag, a sink or mire in mosses or moors.

*Loup, to leap; Iceland, hluap and laup.

*Nowie, horned cattle; Iceland, naut; Dan. noet and noot.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4346) (tudalen 015)

|

Provincial

Words from Newcastle. 1 5

*Reek, or rack, smoke.

Racking-crook, a crane or crook over the fire.

*Sark, shirt

* Smack, to kiss, to taste; Iceland, ee smacki; Dan. smaga. Stour, dust

*Smoored, Dan. smored, anointed, smeared.

Smoored, smothered, suffocated.

*Slot, a young bullock; Dan. an stoud.

*Swinge, to beat, to whip.

Swinging, large, a swinging fellow.

*Toom, teum, or fume, empty.

Tote, whole; the whole tote, phrase.

* Wair, to lay out money, expend.

* Wyte, to blame; to lay the whole wyte on you, phrase. Yule, Christmas; a

yule cake, a Christmas cake.

In Mr. Brand's History of Newcastle, amongst other places, he mentious the

Stock-bridge; and, in a note, enquires, Quaere, Whether the name be derived

from selling stock-fish there? I should think myself obliged to any of your

ingenious correspondents if they would inform me whether the word stock, or

stoke, be not derived from the Saxon, and signifies town or village. There

are many places in this kingdom which have this syllable in the beginning of

their names, as Stockport, Stockton, Stockbridge; and, again, Stokenchurch,

Stoke-uponTrent, etc.; I should, therefore, suppose, that the stock-bridge

was so called from the houses or town which were placed near the bridge.

A SON OF THE TYNE.

Local Words

used in Northumberland.

[1794, Part L, p. 216.]

A Son of the Tyne favoured your readers with a vocabulary of words used by

the natives of Northumberland; in some of which, I think, he has mistaken the

meaning. I therefore take the liberty of sending my explication of them; and

also, of adding a few more words in the Son of the Tyne's vocabulary:

Pant, a fountain. No. Pant signifies the cistern, which receives the

waste-water falling therefrom.

Snech, a latch to the door. It should be wrote sneck, being pronounced hard.

Smasher, a small raised fruit-pie. No. It signifies any thing larger than

common. If there were two or three pies upon a table, of different sizes, the

largest of them would be called a smasher.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4347) (tudalen 016)

|

1 6 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

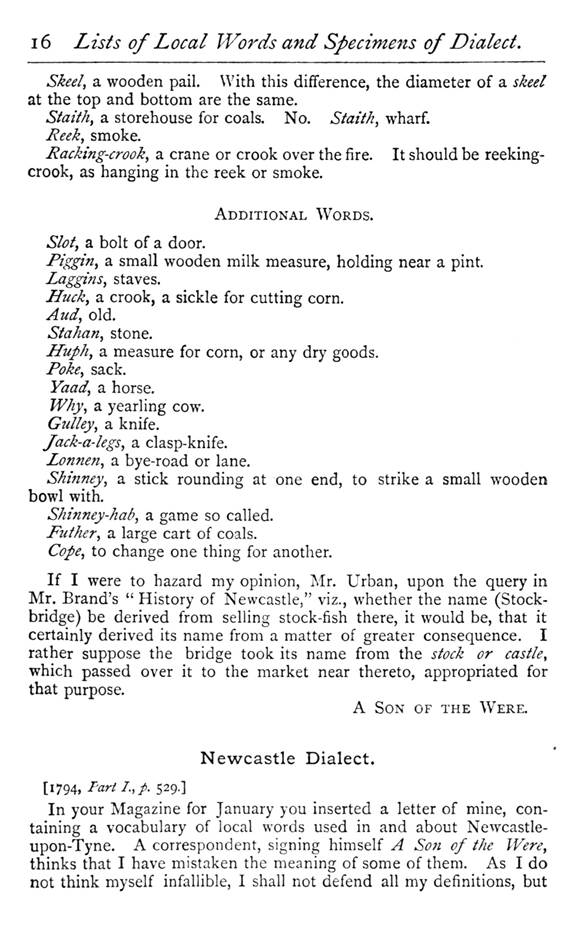

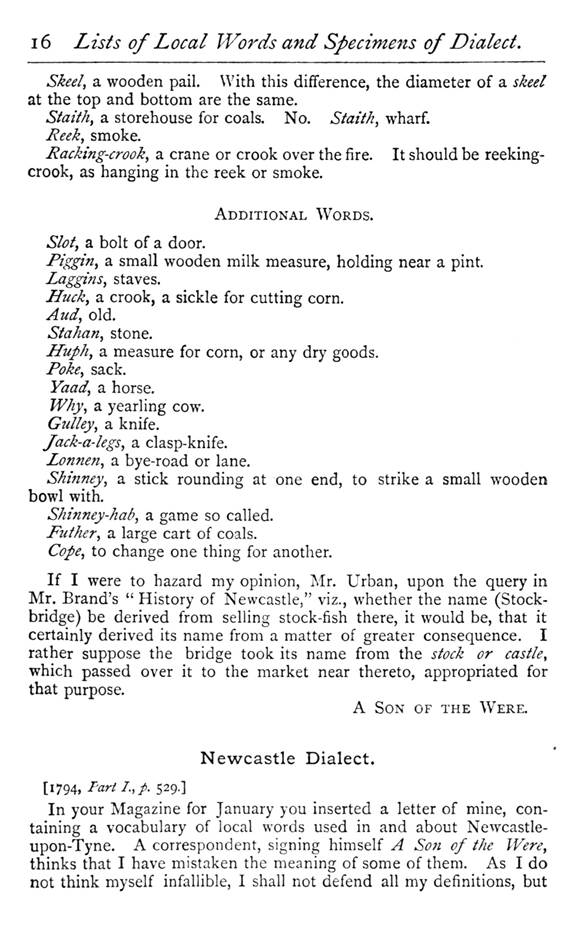

Skeel, a wooden pail. With this difference, the diameter of a skeel at the

top and bottom are the same.

Staith, a storehouse for coals. No. Staith, wharf.

Reek, smoke.

Racking-crook, a crane or crook over the fire. It should be reekingcrook, as

hanging in the reek or smoke.

ADDITIONAL WORDS.

Slot, a bolt of a door.

Pigg* n > a small wooden milk measure, holding near a pint. Laggins,

staves.

ffuck, a crook, a sickle for cutting corn. Aud, old. Stahan, stone.

Huph, a measure for corn, or any dry goods. Poke, sack. Yaad, a horse. Why, a

yearling cow. Gulley, a knife. Jack-a-legs, a clasp-knife. Lonnen, a bye-road

or lane.

Shinney, a stick rounding at one end, to strike a small wooden bowl with.

Shinney-hab, a game so called.

Futher, a large cart of coals.

Cope, to change one thing for another.

If I were to hazard my opinion, Mr. Urban, upon the query in Mr. Brand's

“History of Newcastle," viz., whether the name (Stockbridge) be derived

from selling stock-fish there, it would be, that it certainly derived its

name from a matter of greater consequence. I rather suppose the bridge took

its name from the stock or castle, which passed over it to the market near

thereto, appropriated for that purpose.

A SON OF THE WERE.

Newcastle

Dialect.

[1794, Part I., p. 529.]

In your Magazine for January you inserted a letter of mine, containing a

vocabulary of local words used in and about Newcastleupon-Tyne. A

correspondent, signing himself A Son of the Were, thinks that I have mistaken

the meaning of some of them. As I do not think myself infallible, I shall not

defend all my definitions, but

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4348) (tudalen 017)

|

Local

Words used in Northumberland. 17

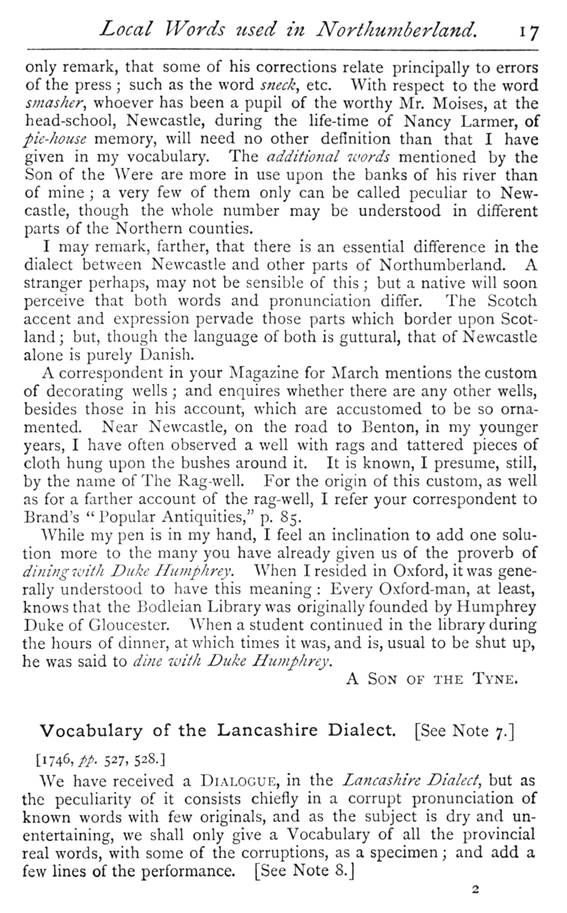

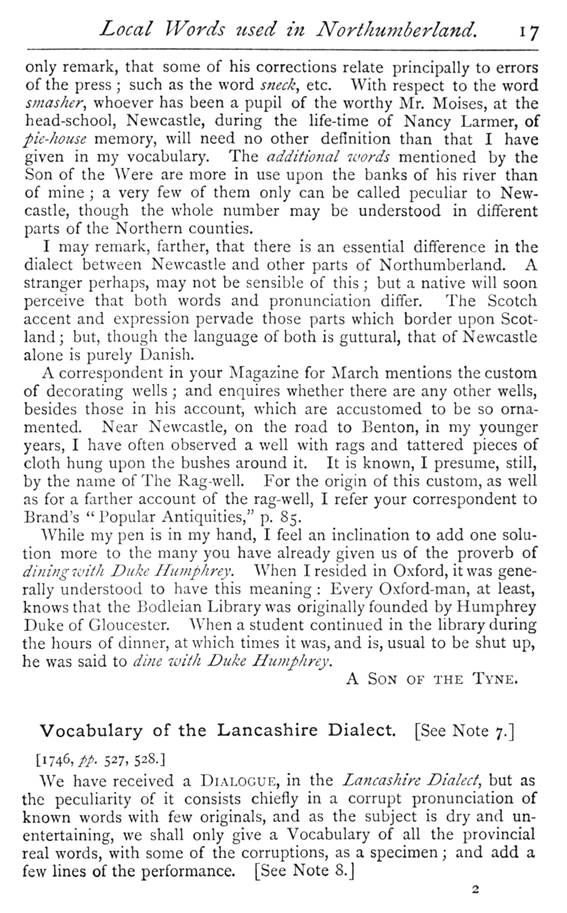

only remark, that some of his corrections relate principally to errors of the

press; such as the word sneck, etc. With respect to the word smasher, whoever

has been a pupil of the worthy Mr. Moises, at the head-school, Newcastle,

during the life-time of Nancy Larmer, of pie-Jwuse memory, will need no other

definition than that I have given in my vocabulary. The additional words

mentioned by the Son of the Were are more in use upon the banks of his river

than of mine; a very few of them only can be called peculiar to Newcastle,

though the whole number may be understood in different parts of the Northern

counties.

I may remark, farther, that there is an essential difference in the dialect

between Newcastle and other parts of Northumberland. A stranger perhaps, may

not be sensible of this; but a native will soon perceive that both words and

pronunciation differ. The Scotch accent and expression pervade those parts

which border upon Scotland; but, though the language of both is guttural,

that of Newcastle alone is purely Danish.

A correspondent in your Magazine for March mentions the custom of decorating

wells; and enquires whether there are any other wells, besides those in his

account, which are accustomed to be so ornamented. Near Newcastle, on the

road to Benton, in my younger years, I have often observed a well with rags

and tattered pieces of cloth hung upon the bushes around it. It is known, I

presume, still, by the name of The Rag-well. For the origin of this custom,

as well as for a farther account of the rag-well, I refer your correspondent

to Brand's “Popular Antiquities," p. 85.

While my pen is in my hand, I feel an inclination to add one solution more to

the many you have already given us of the proverb of dining with Dttke

Humphrey. When I resided in Oxford, it was generally understood to have this

meaning: Every Oxford-man, at least, knows that the Bodleian Library was

originally founded by Humphrey Duke of Gloucester. When a student continued

in the library during the hours of dinner, at which times it was, and is,

usual to be shut up, he was said to dine with Duke Humphrey.

A SON OF THE TYNE.

Vocabulary

of the Lancashire Dialect. [See Note 7.]

[1746, pp. 527,528.]

We have received a DIALOGUE, in the Lancashire Dialect, but as the

peculiarity of it consists chiefly in a corrupt pronunciation of known words

with few originals, and as the subject is dry and unentertaining, we shall

only give a Vocabulary of all the provincial real words, with some of the

corruptions, as a specimen; and add a few lines of the performance. [See Note

8.J

2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4349) (tudalen 018)

|

1 8 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

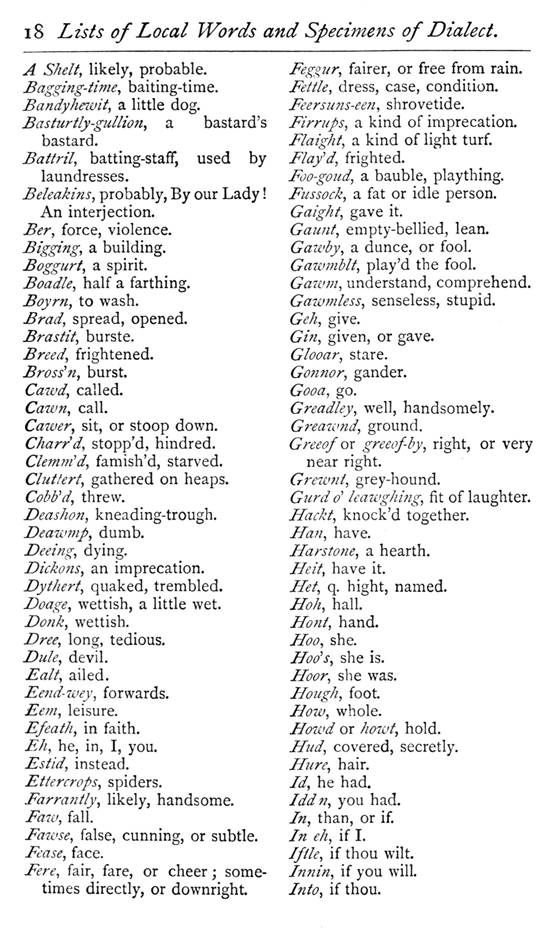

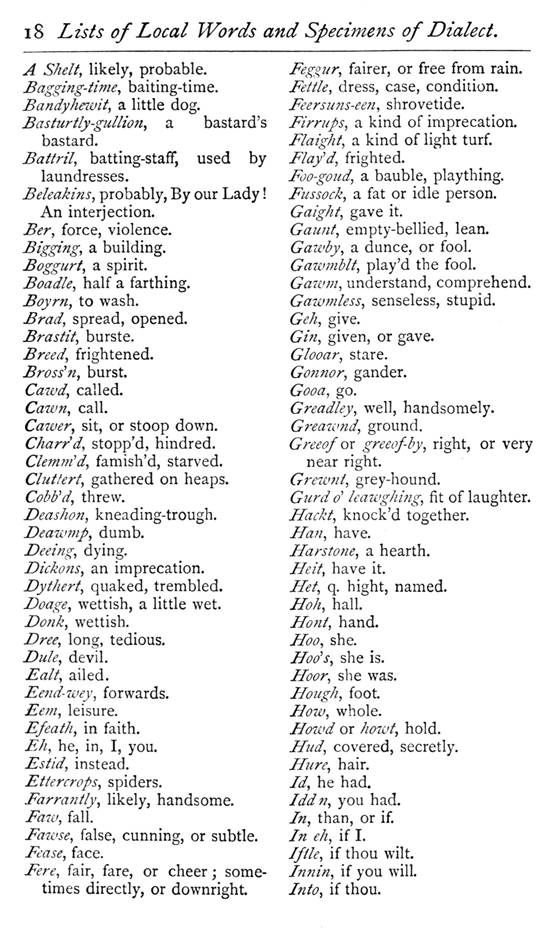

Feggur, fairer, or free from rain.

fettle, dress, case, condition.

Feersu?is-een, shrovetide.

Firrups, a kind of imprecation.

Flaight, a kind of light turf.

Flay'd, frighted.

Foo-goud, a bauble, plaything.

Fussock, a fat or idle person.

Gaight, gave it.

Gaunt, empty-bellied, lean.

Gawby, a dunce, or fool.

Gawmblt, play'd the fool.

Gawm, understand, comprehend.

Gawmless, senseless, stupid.

Geh, give.

Gin, given, or gave.

Glooar, stare.

Gonnor, gander.

Gooa, go.

Greadley, well, handsomely.

Greawnd, ground.

Greeofor greeof-by, right, or very

near right. Greumt, grey-hound. Gurd <?' leawghing, fit of laughter.

Hackt, knock'd together. Han, have. Harstone, a hearth. Heit, have it. Het,

q. hight, named. Hoh, hall. Hont, hand. Hoc, she. Hod's, she is. Hoor, she

was. Hough, foot How, whole. Howd or howt, hold. Hiid, covered, secretly.

Hure, hair. Id, he had. Iddn, you had. In, than, or if. In eh, if I.

y/7/<?, if thou wilt. Innin, if you will. Into, if thou.

A Shelf,

likely, probable.

Bagging-time, baiting-time.

Bandy fiewit, a little dog.

Basturtly-gullion, a bastard's bastard.

Battril, batting-staff, used by laundresses.

Beleakins, probably, By our Lady! An interjection.

Ber, force, violence.

Bigging, a building.

Boggurt, a spirit.

Boadle, half a farthing.

Boyrn, to wash.

Brad, spread, opened.

Brastit, burste.

Breed, frightened.

Bross'n, burst.

Cawd, called.

Cawn, call.

Cawer, sit, or stoop down.

Charrd, stopp'd, hindred.

Clemnfd, famish'd, starved.

Cluttert, gathered on heaps.

CobVd, threw.

Deashon, kneading-trough.

Deawmp, dumb.

Deeing, dying.

Dickons, an imprecation.

Dythert, quaked, trembled.

Doage, wettish, a little wet.

Donk, wettish.

Dree, long, tedious.

Dule, devil.

Ealt, ailed.

Eend-wey, forwards.

Eem, leisure.

Efeath, in faith.

Eh, he, in, I, you.

Estid, instead.

Ettercrops, spiders.

Farrantly, likely, handsome.

Fain, fall.

Fawse, false, cunning, or subtle.

Pease, face.

Fere, fair, fare, or cheer; sometimes directly, or downright.

Vocabidary

of the Lancashire Dialect. 1 9

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4350) (tudalen 019)

|

7V, I was.

1st, I shall, or I shou'd.

Jannock, a kind of loaf bread,

made of oatmeal, leaven'd. Jump, a coat. Keather, cradle. Keem, to comb.

Kele, place, circumstance. Kersun, Christian. Kersmuss, Christmas. Ko, quoth.

Le, let. Ledey, lady.

Leete, let go, to give liberty. Lennock, slender, pliable. LiKt\ likely to

have done. Line, layn.

Least, loosed, or lowest. Lone, lane. Luff, love. Mar, to spoil.

Marry, a common interjection. Matturt, signify 'd. Maundring, walking

stupidly. Meeterly, indifferent. Meet-shad, exceeding. Meh, me, or my. Mexon,

to clean or cleanse. Mey, make. Mich go deet <?', much good may

it do you.

Midding-puce, a sink or sewer. Miss, mass.

Moother, mother, dame. Moofn, might have done. Mowdyivarp, a mole. Nese,

nose.

Ninney-hommer, a natural Nother, neither. Oandurth, afternoon. Gather,

either. Ouoon, above. Obunnunze, abundance. Odd, an interjection. Off ' af

side, mad, delirious. Oforc, before.

Ogreath,

well, right. On, on, and, an, off. Orreawt, without, out of doors. Ost, as

the, as it, offered. Ossing, assaying, offering. Of, at, that. Other-gets,

other sort. Ots, that is. Otteh, that I. Ottle, that thou will. Owd-nick, the

devil. Oytchbody, every one. Phippunny, five-penny. Piss-motes, ants. Pickle,

condition. I Pleck, a place.

;/, pull'd.

P. ist, praised.

Preo, \

Prey y a, } P ra 7 >' ou

Purrd,

kicked.

Pynots, magpyes.

Rachdaw, Rochdale.

Rank, wrong.

Rick, to gingle, or make a noise.

Rindle, mriggot, channel or gutter.

Rook, an heap.

Rotfn, a rat.

Rush-berring, a country wake.

Sark, a shirt.

Saiigh, a kind of willow.

Sau'f, salt.

Sconce, a lantern.

Scrawming, climbing awkwardly.

Seech, seek.

Seete owey, set out.

Seign, seven.

SclFn, self.

Sen, say.

Seroh, Sarah.

Shad, over-did, excell'd.

Shipfin, a cow-house.

Shooder, \ , , , t . 7 ., , ' > shoulder. Shildiir, \

Shoo, shovel or spade. Shoon, shoes.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4351) (tudalen 020)

|

2O Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

Shuntut,

moved, stirred. Sic /i, such. Sin, since. Singlet, a waistcoat. Size, six.

Skrike d dey, break of day. Slifter, a crevice. Slop, a pocket.

Sniff, a moment, very quickly. Snig, an eel. Sope, a sup, very little. Sowd,

sold. Soyn, soon. Sper^d, enquired. Stark, extream, stift. Staivturt, reeled.

Steels, stiles. Steigh, a ladder. Sfoo, a stool. Stoop, a stump of a tree.

Stoar, value. Stoart, valued. Stouni, stolen.

Strackt, quite mad, thorowly. Strey, straw.

Strushon, destruction, waste. Suse, six. Swop, exchange. Sy'd, rained fast.

Sye, to put milk, etc., thro' a sieve; also to be exceeding wet. Ta, to a.

Tat, that.

Team, they were.

Teaw'r, thou were.

7>, thy, they, the.

Thearn, they were.

TJieawst, thou shall

77, than.

ThinKn, think.

Threave, twenty-four.

Throtteen, thirteen.

Thoos'n, those will.

Thwittle, a sort of knive [sic].

J 1 //, a horse, or mare.

Tite, as

well, or handsome.

Tizeday, Tuesday.

Tone, the one.

Too-Too, exceeding.

Tow'd, told.

Toyne, shut.

Toynt, is shut.

Tummus d Ruchat d Margit d RoapJts, q. Thomas of Richard's of Margaret of Ralph's.

Used to distinguish persons, where there are many of the same name in the

same neighbourhood.

Tup, a ram.

Tuppence, two-pence.

* Twur, it were.

Tyney, diminutive.

Unbethowt, remembered.

Uphowd-teh, uphold it thee.

Uphowd o\ uphold it you.

Wanfn, want.

Warcht, ach'd.

Ward, world.

Waughish, qualmish.

Weaughing, barking.

Ween, we have.

Weet, wet, with it.

Weh, with.

Welly, wel-nigh.

Welkin, the sky.

Wetur-tawms, water-qualms, sickfits.

Whackert, quaked, trembled.

Whau, why, well, an interjection.

IVheawtit, whistled.

Whick, quick, alive.

Whinnit, neighed.

Whoavt, covered over.

WJioam, home.

Wimmey, with me,

Win, will.

Winnaiv, will not.

Wonst, once.

Woo, wool.

Wooans, lives, dwells.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4352) (tudalen 021)

|

Vocabulary

of the Lancashire Dialect. 1 1

Woode, mad. Y earth, earth. Wry?wt, to shead wrynot, is to Yigh, yea, yes.

outdo the devil. Yo, you.

Wudyid'n, wish you wou'd. Yoan, you will.

Wur, was. YoacTn, you wou'd.

Yeasing, eave of a house. K?r/, a yard. Yeat, a gate.

SPECIMEN OF THE LANCASHIRE DIALECT.

M. Odds- fish! boh that wur breve 1 wou'd I'd bin eh yore

Kele.

T. Whau, whau, boh theawst hear It wur o dree wey too-to;

heawe'er I geet there be suse o'clock, on before eh opp'nt dur, I covert Nip

with th' cleawt, ot eh droy meh nese weh, t'let him see

heaw I stoart her: Then I opp'nt dur; on what te dule dust

think, boh three little tyney Bandyheivits coom weaughing os if th' little

ewals wou'd o worrit me, on after that swallut me whick: Boh presontly there

coom o fine wummon; on I took her for a hoo justice, hoor so meety fine: For

I heard Ruchott o 1 Jack's tell meh meastor, that hoo justices awlus did th'

mooast o'th' wark: Heawe'er I axt hur if Mr. justice wur o whoam; hoo cou'd

na\v opp'n hur meawth t' sey eigh, or now; boh simpurt on sed iss (the

dikkons iss hur on him too) Sed I, I wuddid'n tell him I'd sene speyk to him.

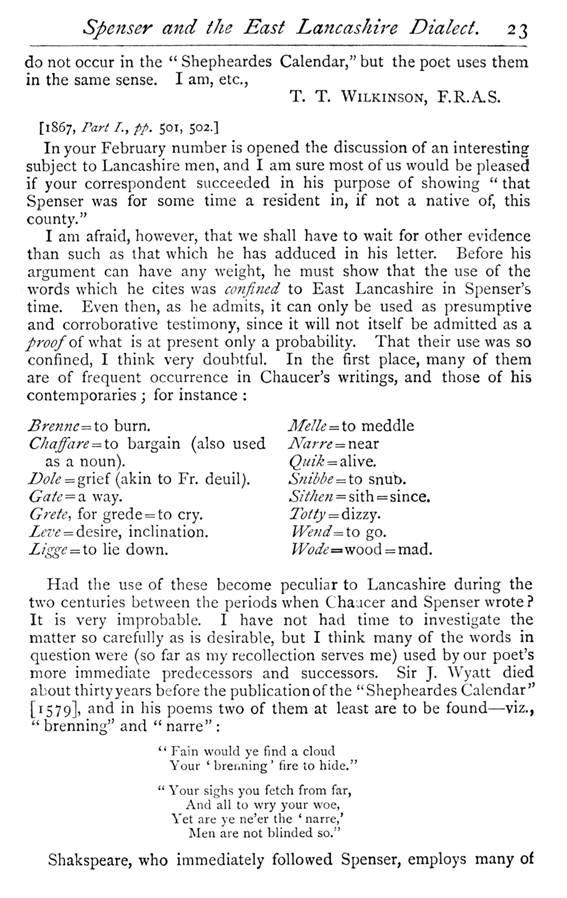

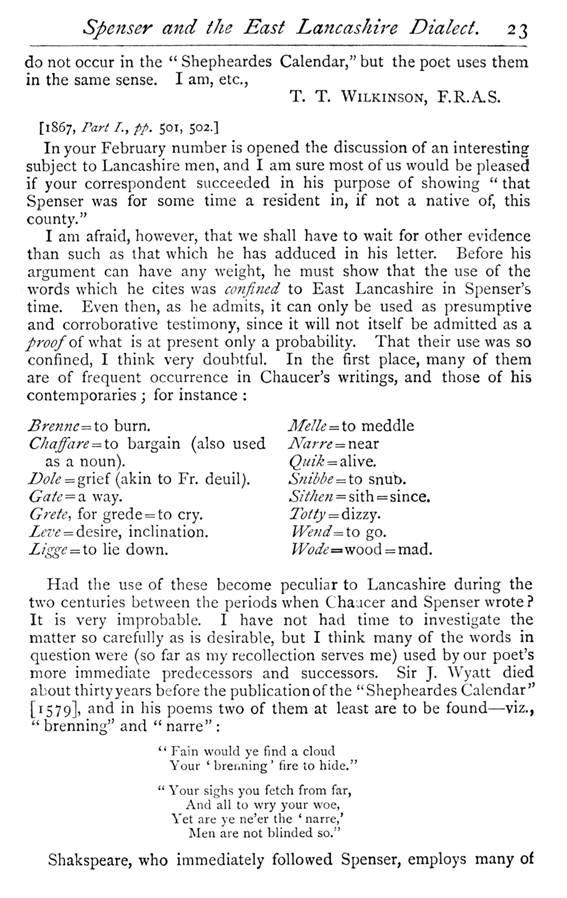

Spenser and the East Lancashire Dialect.

[1867, Fart /., pp. 207, 208.]

The biographers of Edmund Spenser state that after he had taken his degree at

Cambridge, he retired for some time into the North of England, and resided

with his friends. During this sojourn he composed his “Shepheardes

Calendar," and tradition says that this was done at what is now a

farm-house, near Hurstwood, once the residence of a branch of the Towneleys.

The dialect of this part of East Lancashire is somewhat peculiar; inasmuch as

it contains a large admixture of words derived from the Danes and Northmen,

who conquered and colonised this portion of the county of Lancashire. I

therefore examined the “Calendar" with a view of ascertaining whether

any peculiarities of the dialect could be detected, and I soon found abundant

proof that Spenser's countrymen and shepherds made a liberal use of the East

Lancashire dialect. A somewhat hasty perusal furnished the following list;

only two or three of the terms in which are to be found in the South

Lancashire dialect as given by Collier (Tim Bobbin), Bamford, Heywood and

Picton. [See Note 9.]

List of words at present in use in East Lancashire, all of which occur in

Spenser's "Shepheardes Calendar":

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4353) (tudalen 022)

|

22 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

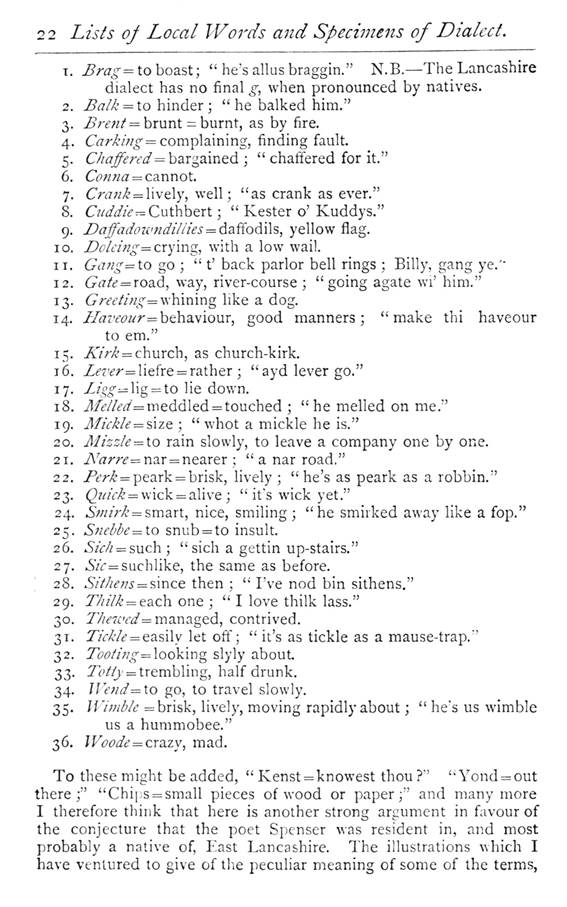

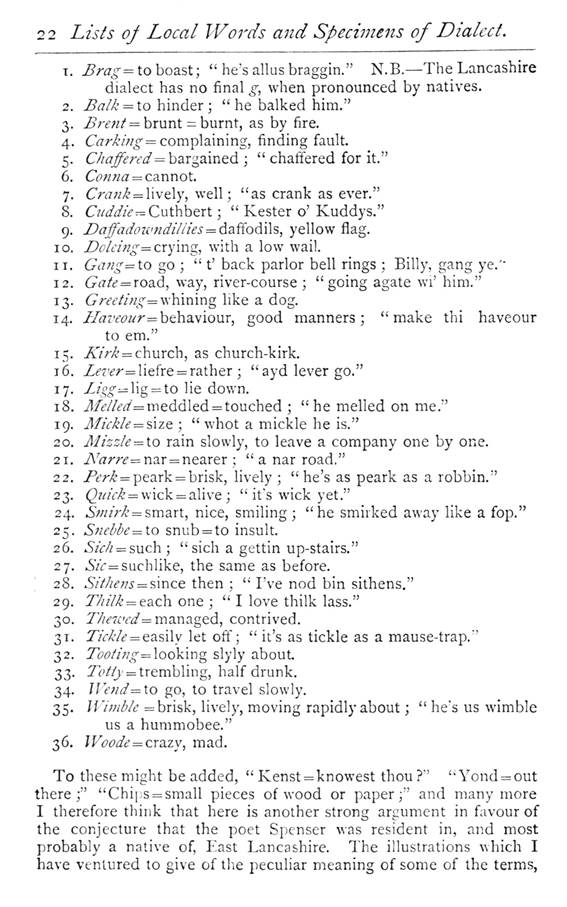

T. Brag= to boast; "he'sallusbraggin." N.B. The Lancashire dialect

has no final g, when pronounced by natives.

2. Balk = to hinder; “he balked him."

3. Brent = brunt = burnt, as by fire.

4. Carking= complaining, finding fault.

5. Chaffered = bargained; “chaffered for it."

6. Conna = cannot.

7. Crank= lively, well; "as crank as ever."

8. <7<///a?=Cuthbert; “Kester o' Kuddys."

9. Daffadowndillies = daffodils, yellow flag.

10. Doleing= crying, with a low wail.

11. Gang=io go; “t' back parlor bell rings; Billy, gang ye."

12. Gate=roa.d, way, river-course; "going agate wi' him."

13. Greeting= whining like a dog.

14. Haveour= behaviour, good manners; "make thi haveour

to em."

15. Kirk church, as church-kirk.

16. Lever= liefre = rather; "ayd lever go."

17. Lig\\g = \.Q lie down.

18. Melled meddled = touched; “he melled on me."

19. Mickle=s\zo.; “whot a mickle he is."

20. Mizzle to rain slowly, to leave a company one by one.

21. JVarre=r\a.r= nearer; "a nar road."

22. /Vr^=peark= brisk, lively; "he's as peark as a robbin."

23. Quick wick = alive; “it's wick yet."

24. Smirk= smart, nice, smiling; "he smirked away like a fop."

25. Snebbe=lo snub = to insult.

26. Stc/i = such; “sich a gettin up-stairs."

27. Sic suchlike, the same as before.

28. Sithens= since then; “I've nod bin sithens."

29. 277>=each one; “I love thilk lass."

30. Theu<ed= man aged, contrived.

31. Tickle = easily let off; “it's as tickle as a mause-trap."

32. Tooting = looking slyly about

33. Totty trembling, half drunk.

34. Wend=\.Q go, to travel slowly.

35. Wimble = brisk, lively, moving rapidly about; “he's us wimble

us a hummobee."

36. Woode= crazy, mad.

To these might be added, "Kenst=knowest thou?" "Yond = out

there;" "Chips = small pieces of wood or paper;" and many more

I therefore think that here is another strong argument in favour of the

conjecture that the poet Spenser was resident in, and most probably a native

of, East Lancashire. The illustrations which I have ventured to give of the

peculiar meaning of some of the terms,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4354) (tudalen 023)

|

Spenser

and the East Lancashire Dialect. 23

do not occur in the “Shepheardes Calendar," but the poet uses them in

the same sense. I am, etc.,

T. T. WILKINSON, F.R.A.S.

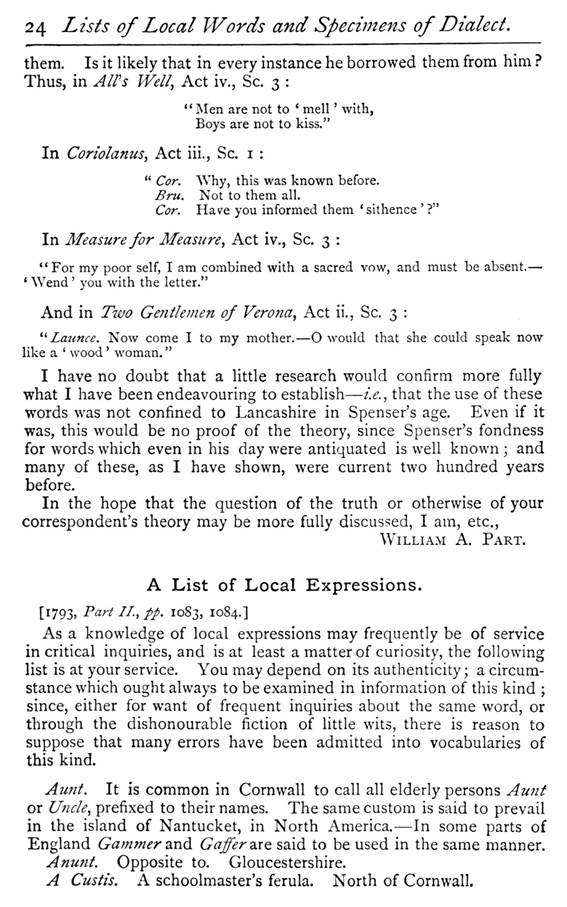

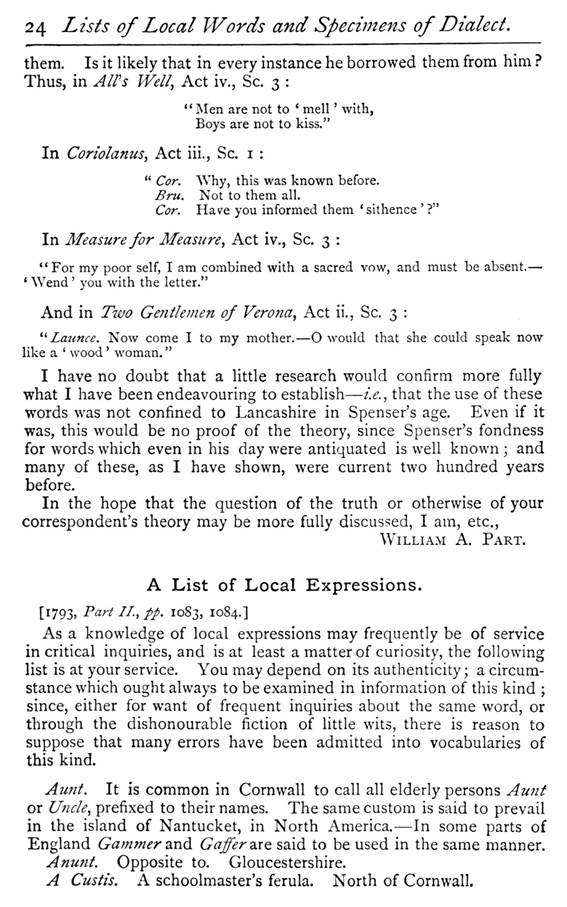

[1867, Part /., pp. 501, 502.]

In your February number is opened the discussion of an interesting subject to

Lancashire men, and I am sure most of us would be pleased if your

correspondent succeeded in his purpose of showing “that Spenser was for some

time a resident in, if not a native of, this county."

I am afraid, however, that we shall have to wait for other evidence than such

as that which he has adduced in his letter. Before his argument can have any

weight, he must show that the use of the words which he cites was confined to

East Lancashire in Spenser's time. Even then, as he admits, it can only be

used as presumptive and corroborative testimony, since it will not itself be

admitted as a proof of what is at present only a probability. That their use

was so confined, I think very doubtful. In the first place, many of them are

of frequent occurrence in Chaucer's writings, and those of his

contemporaries; for instance:

Brennc=\.Q burn. Melle-iQ meddle

Chaffare=\.o bargain (also used 7Va;T=near

as a noun). Quik = alive.

Dole = grief (akin to Fr. deuil). Snibbe\.Q snub.

Gate = a way. Sitfan = s\\.h = since.

Grete, for grede = to cry. Totty = dizzy.

Leve= desire, inclination. lend=\.o go.

Ligge=\.o lie down. Wode= wood = mad.

Had the use of these become peculiar to Lancashire during the two centuries

between the periods when Chaucer and Spenser wrote? It is very improbable. I

have not had time to investigate the matter so carefully as is desirable, but

I think many of the words in question were (so far as my recollection serves

me) used by our poet's more immediate predecessors and successors. Sir J.

Wyatt died about thirty years before the publication of the "Shepheardes

Calendar" [1579], and in his poems two of them at least are to be found

viz., “brenning" and “narre":

“Fain would ye find a cloud Your ' brenning ' fire to hide."

“Your sighs you fetch from far,

And all to wry your woe,

Yet are ye ne'er the ' narre,'

Men are not blinded so."

Shakspeare, who immediately followed Spenser, employs many of

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4355) (tudalen 024)

|

24 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

them. Is it likely that in every instance he borrowed them from him? Thus, in

All's Well, Act iv., Sc. 3:

"Men are not to ' mell ' with, Boys are not to kiss."

In Coriolanus, Act iii., Sc. i:

“Cor. Why, this was known before. Bru. Not to them all. Cor. Have you

informed them 'sithence '?"

In Measure for Measure, Act iv., Sc. 3:

"For my poor self, I am combined with a sacred vow, and must be absent.

' Wend ' you with the letter."

And in Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act ii., Sc. 3:

"Launce. Now come I to my mother. O would that she could speak now like

a ' wood ' woman. “

I have no doubt that a little research would confirm more fully what I have

been endeavouring to establish i.e., that the use of these words was not

confined to Lancashire in Spenser's age. Even if it was, this would be no

proof of the theory, since Spenser's fondness for words which even in his day

were antiquated is well known; and many of these, as I have shown, were

current two hundred years before.

In the hope that the question of the truth or otherwise of your correspondent's

theory may be more fully discussed, I am, etc.,

WILLIAM A. PART.

A List of

Local Expressions.

[1793, Part II., pp. 1083, 1084.]

As a knowledge of local expressions may frequently be of service in critical

inquiries, and is at least a matter of curiosity, the following list is at

your service. You may depend on its authenticity; a circumstance which ought

always to be examined in information of this kind; since, either for want of

frequent inquiries about the same word, or through the dishonourable fiction

of little wits, there is reason to suppose that many errors have been

admitted into vocabularies of this kind.

Aunt. It is common in Cornwall to call all elderly persons Aunt or Uncle,

prefixed to their names. The same custom is said to prevail in the island of

Nantucket, in North America. In some parts of England Gammer and Gaffer are

said to be used in the same manner.

Anunt. Opposite to. Gloucestershire.

A Custis. A schoolmaster's ferula. North of Cornwall.

|

|

|

|

|

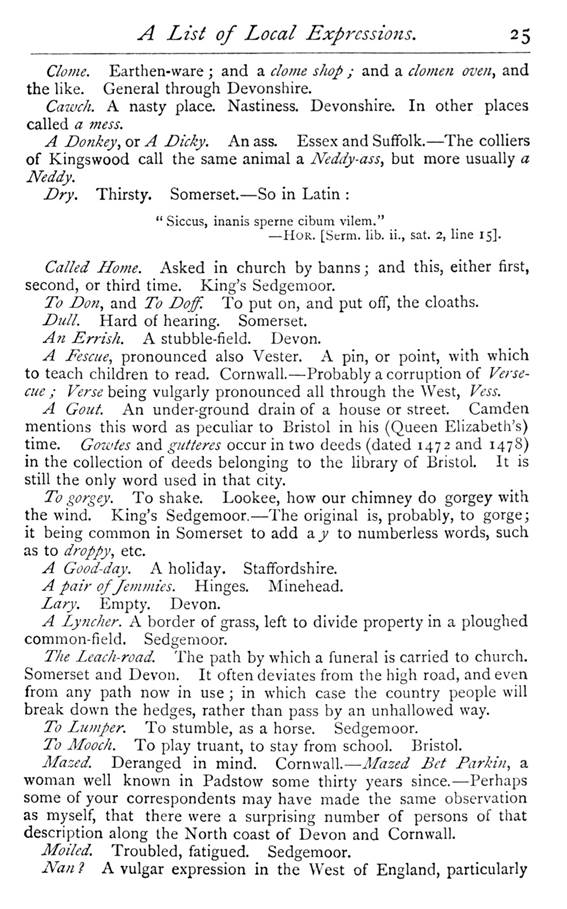

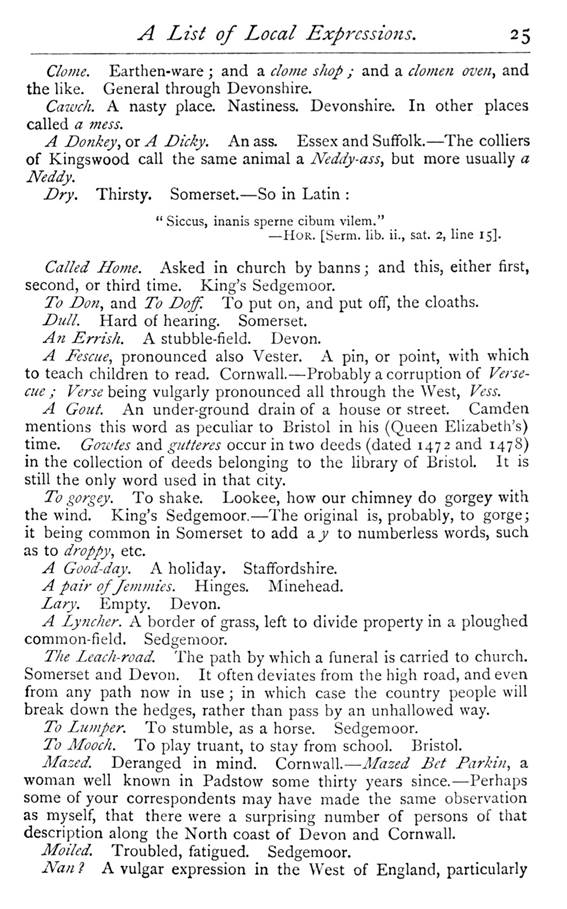

(delwedd D4356) (tudalen 025)

|

A List of

Local Expressions. 25

dome. Earthen-ware; and a dome shop; and a clomen oven, and the like. General

through Devonshire.

Cawch. A nasty place. Nastiness. Devonshire. In other places called a mess.

A Donkey, or A Dicky. An ass. Essex and Suffolk. The colliers of Kingswood

call the same animal a Neddy-ass, but more usually a Neddy.

Dry. Thirsty. Somerset. So in Latin:

“Siccus, inanis sperne cibum vilem."

HOR. [Serin, lib. ii., sat. 2, line 15].

Called Home. Asked in church by banns; and this, either first, second, or

third time. King's Sedgemoor.

To Do?i, and To Doff. To put on, and put off, the cloaths.

Dull. Hard of hearing. Somerset.

An Errish. A stubble-field. Devon.

A Fescue, pronounced also Vester. A pin, or point, with which to teach

children to read. Cornwall. Probably a corruption of Versecue; Verse being

vulgarly pronounced all through the West, Vess.

A Gout. An under-ground drain of a house or street. Camden mentions this word

as peculiar to Bristol in his (Queen Elizabeth's) time. Gowtes and gutteres

occur in two deeds (dated 1472 and 1478) in the collection of deeds belonging

to the library of Bristol. It is still the only word used in that city.

To gorgey. To shake. Lookee, how our chimney do gorgey with the wind. King's

Sedgemoor. The original is, probably, to gorge; it being common in Somerset

to add a y to numberless words, such as to droppy, etc.

A Good-day. A holiday. Staffordshire.

A pair of Jemmies. Hinges. Minehead.

Lary. Empty. Devon.

A Lyncher. A border of grass, left to divide property in a ploughed

common-field. Sedgemoor.

The Leach-road. The path by which a funeral is carried to church. Somerset

and Devon. It often deviates from the high road, and even from any path now

in use; in which case the country people will break down the hedges, rather

than pass by an unhallowed way.

To Lumper. To stumble, as a horse. Sedgemoor.

To Mooch. To play truant, to stay from school. Bristol.

Mazed. Deranged in mind. Cornwall. Mazed Bet Parkin, a woman well known in

Padstow some thirty years since. Perhaps some of your correspondents may have

made the same observation as myself, that there were a surprising number of

persons of that description along the North coast of Devon and Cornwall.

Moiled. Troubled, fatigued. Sedgemoor.

Nan? A vulgar expression in the West of England, particularly

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4357) (tudalen 026)

|

26 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

in Gloucestershire, which means what do you say? Ha, or Hai, is commonly used

for the same. In the neighbourhood of Sedgemoor, say, ma'am say, sir, is very

common.

Nes/i. Soft, tender. It is applied to the health, and means delicate

Somerset.

A Peel. A pillow. Somerset and Devon.

Pillum. Dirt. Devon.

A Picksey. A fairy. Somerset, Devon, and Cornwall Pickseyled, bewildered, led

astray, particularly in the night, by a Jack-alantern, which is believed to

be the work of the Picksies.

A Plough. A waggon, or cart, or plough, together with the team which draws

it, is called by no other name in several parts of Somersetshire.

To drive the pray. To drive the cattle from the moor. Sedgemoor. French,

pres, a meadow.

Retchup, so pronounced, though the original is probably Rightship. Truth.

Somersetshire. As, There is no retchup in that child.

A Rail. A revel, a country wake. Devon.

A Slice. A fire-shovel. Bristol.

Stive. Dust. Pembrokeshire. Dust is there only used to signify saivdust.

To Sar. To earn. Sedgemoor. As, To sar seven shillings a week. The same word

is also used as a corruption of serve; as, To sar the pigs.

A Scute. A reward. North of Devon.

To Slotter. To slop, to mess, to dirt. Devon.

Sture. Dust. Devon.

To Slock. To pilfer, or give privately; and a Slockster, a pilferer. Devon

and Somerset.

To for at. All over Devon.

Th for 6" in the third person singular of verbs. Devon. As, // rainth He

livth to Parracomb When Jie jumpth, all shaketh.

Tidy. Neat, decent. West of England.

To Tine. To light, etc. As, Tine the candle. Somerset. Pronounced, in Devon,

Tin.

To Tine is likewise used in the neighbourhood of Sedgemoor for to shut. As,

Tine the door He has not tined his eyes to sleep these three nights.

A Tutty. Pronounced also, in other places, a Titty. A nosegay. Somerset.

Ttvily. Restless. Somerset. Perhaps a corruption of Toily.

Tutt-work. Jobb-work, as distinguished from work by the day. Somerset and

Devon; and in the Cornish and Derbyshire mines. Probably derived from the

French tout.

Unkid, or Uncut. Dull, melancholy. Somerset.

Vitty. Neat, decent, suitable. Cornwall. Perhaps a corruption of Fit or

Fetive.

|

|

|

|

|

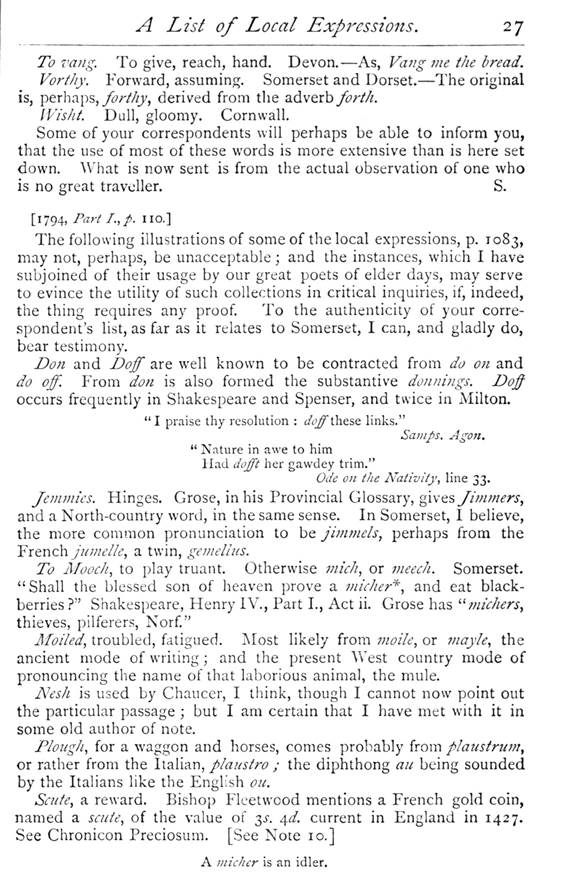

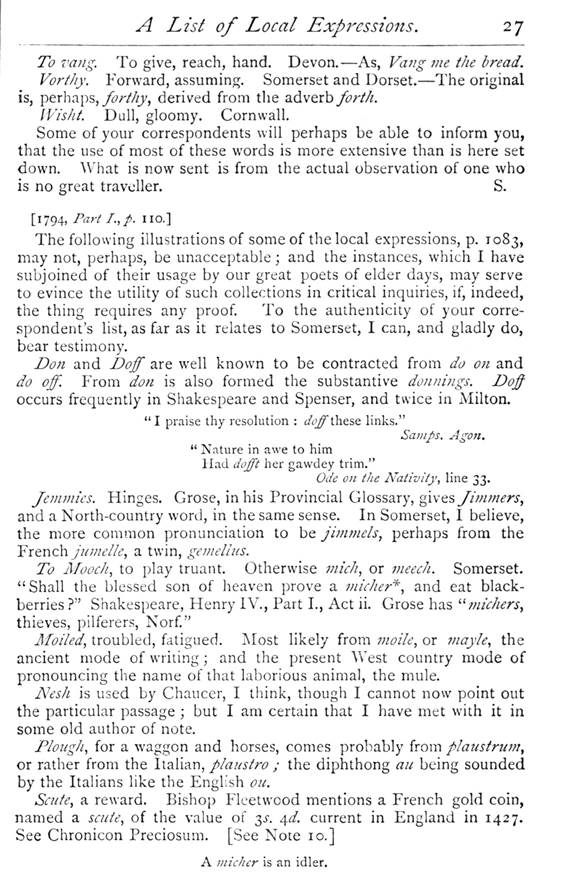

(delwedd D4358) (tudalen 027)

|

A List of

Local Expressions. 27

To rang. To give, reach, hand. Devon. As, Vang me the bread.

Vorthy. Forward, assuming. Somerset and Dorset. The original is, perhaps,

forthy, derived from the adverb forth.

Wisht. Dull, gloomy. Cornwall.

Some of your correspondents will perhaps be able to inform you, that the use

of most of these words is more extensive than is here set down. What is now

sent is from the actual observation of one who is no great traveller. S.

[1794, Part L, p. no.]

The following illustrations of some of the local expressions, p. 1083, may

not, perhaps, be unacceptable; and the instances, which I have subjoined of

their usage by our great poets of elder days, may serve to evince the utility

of such collections in critical inquiries, if, indeed, the thing requires any

proof. To the authenticity of your correspondent's list, as far as it relates

to Somerset, I can, and gladly do, bear testimony.

Don and Doff are well known to be contracted from do on and do off. From don

is also formed the substantive donnings. Doff occurs frequently in

Shakespeare and Spenser, and twice in Milton.

“I praise thy resolution: doff these links."

Samps. Agon. “Nature in awe to him Had dofft her gavvdey trim."

Ode on the Nativity, line 33.

Jemmies. Hinges. Grose, in his Provincial Glossary, gives Jimmers, and a

North-country word, in the same sense. In Somerset, I believe, the more

common pronunciation to be jimmels, perhaps from the French jumelle, a twin,

gemellus.

To Mooch, to play truant. Otherwise mich, or meech. Somerset. "Shall the

blessed son of heaven prove a micher*, and eat blackberries?"

Shakespeare, Henry IV., Part I., Act ii. Grose has "michers, thieves,

pilferers, Norf."

Moiled, troubled, fatigued. Most likely from moile, or mayle, the ancient

mode of writing; and the present West country mode of pronouncing the name of

that laborious animal, the mule.

Nesh is used by Chaucer, I think, though I cannot now point out the

particular passage; but I am certain that I have met with it in some old

author of note.

Plough, for a waggon and horses, comes probably from plaustrum, or rather

from the Italian, plaustro; the diphthong au being sounded by the Italians

like the English ou.

Scute, a reward. Bishop Flcetwood mentions a French gold coin, named a scute,

of the value of 3^. $d. current in England in 1427. See Chronicon Preciosum.

[See Note 10.]

A micher is an idler.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4359) (tudalen 028)

|

28 Lists

of Local Words and Specimens of Dialect.

Tidy, neat, decent. Dol Tear-sheet calls FalstafT, “thou whoreson little

tydie Bartholomew Boar-pig." Henry IV., Part II., Act ii. Tine, to

light. As, Tine the candle. Thus Milton,

“as late the clouds

Justling, or pushed with winds, rude in their shock, Tine the slant

lightning."

Par. Lo. B. X. 1. 332.

Tine, to shut. Verstegan gives, "betined, hedged about," in his

list of old English words; and adds, “We use yet in some parts of England to

say tyning for hedging." Antiquities, ed. 4to., 1634, p. 210. In