|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4449) (tudalen 120)

|

120 Proverbial Phrases.

A good sword and a trusty hand,

A merry heart and true;

King James's men shall understand

What Cornish men can do.

And have they fix'd the where and when?

And shall TRELAWNY die?

Then twenty thousand Cornish men

Will know the reason why!

Out spake the Captain brave and bold,

A merry wight was he,

Though London Tower were Michael's* hold,

We'd set TRELAWNY free!

We'll cross the Tamar, land to land,

The Severn is no stay;

And side to side, and hand in hand,

And who shall bid us nay?

And when we come to London Wall,

A pleasant sight to view,

Come forth! come forth! ye cowards all;

Here are better men than you.

TRELAWNY he's in keep and hold;

TRELAWNY he may die!

But twenty thousand Cornish bold

Will know “The Reason Why."

U. P. K. spells Goslings.

[1791, Part L, p. 327.]

“U. P. K. spells May goslings," is an expression used by boys at play,

as an insult to the losing party. U. P. K. is up-pick, that is, up with your

pin or peg, the mark of the goal. An additional punishment was thus: the

winner made a hole in the ground with his heel, into which a peg about three

inches long was driven, its top being below the surface; the loser, with his

hands tied behind him, was to pull it up with his teeth, the boys buffeting

with their hats, and calling out, “Up pick, you May Gosling;" or “U. P.

K. Gosling in May." A May Gosling, on the first of May, is made with as

much eagerness in the North of England, as an April noddy (noodle) or fool,

on the first of April.

In 1688, when James II. left the kingdom, a rising of the Roman Catholicks

was expected in the South of Lancashire, when an order was issued, as said,

by the Earl of Derby, for the men of the Northern

* St. Michael's Mount.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4450) (tudalen 121)

|

Wake. 121

parts, from sixteen to sixty years of age, to meet at Kirkby Lonsdale, a town

on the borders of Lancashire and Westmorland, with a fortnight's provision,

and with such armour as could be procured, on pain of being hanged up at

their own doors: numbers came, but no enemy appearing, after staying their

time, they departed. The following verse is yet remembered, and made on that

occasion:

In eighty-eight was Kirkby feight (fight),

When ne'er a man was slain; They eat their meat, and drank their drink,

And so went yham (home) again.

Why diamonds are called picks seems to be from the sharp points, picked or

pointed, a pick being a tool, used in digging in stony ground, with two sharp

points: hence hearts, clubs, spades, and picks.

W. Wake.

[1771, / 351-1

As the expression lately used in the papers in an article from Ireland

concerning a girl who was killed by lightning, viz., "that she could not

be waked within doors “(after she was dead) seems unintelligible to most

readers, it may be proper to mention, that it alludes to a custom among the

Irish of dressing their dead in their best cloaths to receive as many

visitors as please to see them; and this is called keeping their wake. The

corpse of this girl, it seems, was so offensive that this ceremony could not

be performed. [NOTE. There are two pages numbered 351 in this volume.]

W. G.

Wine of One Ear.

[1812, Part I., p. 38.]

In "Rabelais' Works," by Ozell, 1750, vol. i., p. 154, occurs this

note:

“Wine of one ear. A proverbial expression for excellent good wine. In some

parts of Leicestershire and elsewhere, speaking of good ale, ale of one ear;

bad ale, ale of two ears. Because when it is good, we give a nod with one

ear; if bad, we shake our head, that is, give a sign with both ears that we

don't like it."

Not having met with this proverbial expression in any other writer, I should

be glad to know to what county it is properly to be appropriated.

H. [1832, Part I., p. 239.]

Your Correspondent H. cites a proverbial expression from Rabelais' works by

Ozell, “Wine of one ear," and solicits an explanation of it. I apprehend

that he mistakes in supposing this to be an

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4451) (tudalen 122)

|

122 Proverbial Phrases.

English proverbial expression, and that it is derived from the French, though

erroneously translated, who have this proverb, which they apply to anything

that is crude, immature, "Vin d'une Anne." From which it appears

that it should be "wine of one year," and not of "one ear/'

wine of only one year old, or new wine, not being in estimation. [See note 32.]

Yours, etc., R. E. R.

As the Devil loves Apple-Dumplings.

[1858, Part //.,/. 401.]

This is a not uncommon saying, but to all appearance a very silly one. About

a century and a quarter ago it was the custom to give the students of certain

colleges at Oxford Hart Hall, for example; Oxford men will forgive the

apparent misnomer nothing but appledumplings for their dinner on fast-days;

every Friday, for example. The flesh rebelling against such unsubstantial

diet, a proverbial saying may have thence arose to the effect that the devil

was no lover of apple-dumplings. That the students complained bitterly of Dr.

Newton's apple-dumplings, there is no doubt, printed authority being still in

existence to that effect

[1772, / 529-]

[The following is quoted at the above reference from a review of a play, The

Irish Widow, then just published, and performed at Drury Lane.]

Wife a mouse, Quiet house; Wife a cat, Dreadful that.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4452) (tudalen 124)

|

Special Words.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4453) (tudalen 125)

|

SPECIAL WORDS.

Apple of the Eye.

[1833, Parti., pp. 30, 31.]

VARIOUS unsatisfactory attempts have been made, in Boucher's “Glossary of

Archaisms," to give a rational derivation of the Biblical expression,

the “apple of the eye." The fact is, that apple, a corruption of the

Teutonic ap-fel, i.e., ^fall-from, where the German ap is the same as the

Latin ab, and Greek aero (apo\ never had nor could have anything to do with

the eye; and therefore the origin of the word must be sought for elsewhere.

Now it does so happen that in the Coptic language bal means the ball of the

eye. Hence apple would only be a corruption of al-bal where al, the definite

article, has been united to the noun, as in Alchemist, Al-coran, Al-magist,

and Al-manach, with all of which we are accustomed to repeat the article,

when speaking of the Alchemist, the Alcoran, the Almagist, and the Almanach;

and thus the apple would be only another example of the repetition of the

definite article the al-bal, of which the Latin orb-is is a still greater

corruption. Of the Coptic Bal, the radical consonants are BL, which, by the

insertion of the five vowels a, e, i, o, u, have given rise to an infinity of

words in various languages, all referable to some property of the eye.

Aroint.

[1832, Part IL,pp. 594, S9S-]

Your learned Correspondent, in p. 228, has attempted to elucidate and explain

the word aroint, in Shakespeare. Although he refers to Boucher's “Glossary of

Archaic and Provincial Words," to Wilbraham's “Cheshire Glossary,"

and to Collier's “Lancashire Dialect," he appears still dissatisfied

with the etymology of the word. He thinks it probable that ronyan may be French

or Italian; but that it is by no means evident that the word aroint has the

same derivation.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4454) (tudalen 126)

|

126 Special Words.

I refer your correspondent to the Rev.

Wra. Carr's second edition of the “Craven Glossary," from which it

appears that in that district of the West Riding of Yorkshire, the mountain

ash, the sorbus aneuparia of Linnaeus, was called royan tree, and was

supposed by the inhabitants to have wonderful efficacy in depriving witches

of their infernal power. The learned editor of Boucher's “Glossary “calls

aroint an interjection; but in the “Craven Glossary," the royntree (of

which aroint may be supposed a corruption) conveys the sense of a triumphant

exclamation. As your correspondent may not have seen the second edition of

the “Craven Glossary," I will extract for his information the whole of

the reverend author's remarks on the word royntree, which, in my judgment,

forcibly elucidate the meaning of the word aroint:

Royntree, Roantree, Rowantree^ Rantree, Wicken, Wigan, Wibele Hazel: Mountain

Ash, sorbus aneuparia , Linn. Dan. Roune.

Thompson, in his Etymons, says that the word aroynt signifies reprobation,

from Gothic raun; a tree of wonderful efficacy in depriving witches of their

infernal power; and she was accounted a very thoughtless house-wife who had

not the precaution to provide a churnstaff made of this precious wood. When

thus guarded, no witch, however presumptuous, had the audacity to enter.

Sometimes a small piece of it was suspended from the button-hole, which had

no less efficacy in defending the traveller. May not the sailor's wife, in

Macbeth, have confided in the divine aid of this tree when she triumphantly

exclaimed, “aroynt thee!" alias, “a royntree! With the supernatural aid

of this," pointing, it may be supposed at the royntree in her hand, “I

defy thy infernal power." The event evidently proved her security; for

the witch, having no power over her, so completely protected, indignantly and

spitefully resolves to persecute her inoffensive, though unguarded husband on

his voyage to Aleppo. Mr. Wilbraham, in his “Cheshire Glossary," says,

“Possibly aroynt owes its origin to the old adverb arowme, found in

Promptorium Parvulorum Clericorum [see note 33]; and there explained by

remote seorsum, or from ryman, or reunean, A.-S., to get out of the way

"Rym thysummen sell, give this man place." "Saxon

Gospels," Luke xiv. 9.

It was said two hogsheads full of money were concealed in a subterraneous

vault at Penyard Castle, in Herefordshire. A farmer took twenty steers to

draw down the iron doors of the vault. When the door was opened, a crow or a

jackdaw was seen perched on one of the casks; as the door was opening, the

farmer exclaimed, “I believe I shall have it." Whereupon the door

immediately closed, and a voice without exclaimed

“If it had not been for your quicken-tree goad and your yew-tree pin, You and

your cattle had all been drawn in."

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4455) (tudalen 127)

|

Aroint. 127

This story has some resemblance to the curious nonsense concerning a cave and

a cock, related in Dugdale's "Warwickshire," p. 619, ed. i, because

the prophylactic properties of the quicken- tree (mountain ash) shew an

incorporation with Druidical superstition; for we believe these ancient

personages were accustomed to delude the people with wonders. In the song of

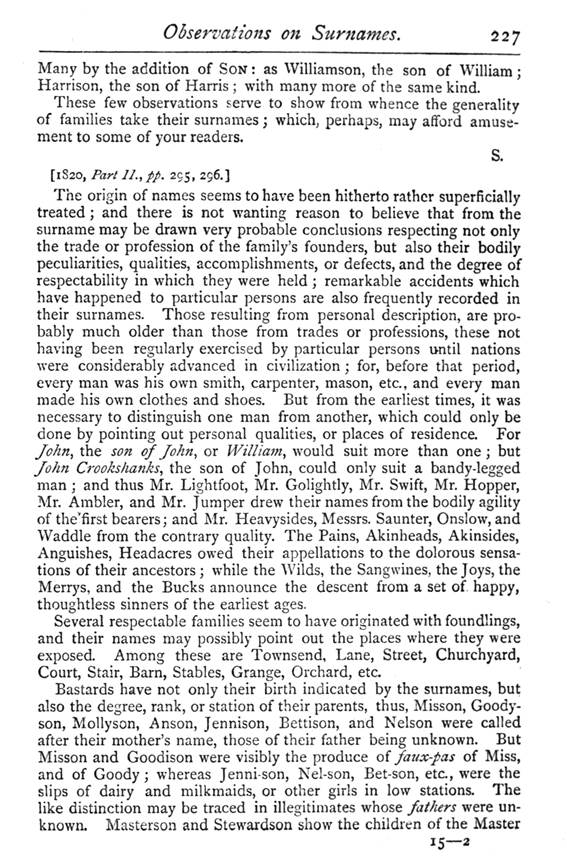

the Laidley Worm, in "Northumberland Garland," p. 63, we read

“The spells were vain, the Hag returns To the Queen in sorrowful mood, Crying

that witches have no power Where there is rown-tree wood!"

Brand's "Pop. Ant." vol. ii., p. 370.

“I go to Mother Nicneran's," answered the maid; “and she is witch enough

to rein the horned devil, with a red silk for a bridle, and a rowan-tree

switch for a whip." Abbot.

“In my plume is seen the holly green, With the leaves of the rown-tree."

“Minst. of S. B.," vol. iii., p. 290.

Not long ago, as a sagacious farmer in my neighbourhood was driving his

plough, the horses instantaneously became restive. The whip was most

rigorously applied without any effect whatever upon the horses, which still

continued motionless. The farmer very fortunately cast his eyes on a

wicken-tree, which was growing in the adjoining hedge; he speedily cut from

it a twig, when lo! the most gentle application of this divine plant broke

the witches' infernal spell, and caused the horses to proceed quietly with

their accustomed toils! Credat Judeas!

“Wi rown-tree weel fenced about,

We're seafe frae every evil; For weel I ken that wood has power To scar away

the deevil."

Stag's “Poems." [See note 34.]

"And money a panting heart was there

That bode full bitter picks, For tho' wi witch-wood weard yet weel, They kend

auld Hornie's tricks."

“The Panic," Idem.

This species of superstition which, in England and Scotland, attaches to the

rown-tree, Bishop Heber, in his Journal, informs us, is paid by the Indians

to a species of mimosa, the leaves of which so much resemble the mountain

ash. “Though it did not bear fruit the natives observed it was a noble tree,

being called the ' Imperial tree,' for its excellent properties: that it

slept all night, and wakened and was alive all day, withdrawing its leaves if

anyone attempted to touch

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4456) (tudalen 128)

|

128 Special Words.

them; a sprig, worn in the turban, or

suspended over the bed, was a perfect security against all spells, an evil

eye, etc. From what common centre are all these notions derived?" Bishop

Heber's "Journal," vol. ii., p. 252.

Yours, etc., OXONIENSIS.

[1788, Part I I., p. 392.]

Allow me to venture a conjecture on a passage in Shakespeare. In Mr. Ray's

“Collection of English Words," Rynt ye is thus explained: “By your leave,

stand handsomely. As Rynt you Witch, quoth Besse Locket to her mother proverb

Cheshire." Compare with this the following passage in Macbeth, and

Johnson's note on it, p. 378: “ist Witch. A sailor's wife had chesnuts in her

lap, and mouncht, and mouncht. Give me, quoth I. Aroint thee, witch! the

rump-fed runyon cries." When the witch roughly cries, "Give

me," it is natural that the sailor's wife should use a common proverb to

reprove her for her ill manners. [See note 35.]

Assassin.

[i 768, //. 326, 327-]

The word assassin, whence comes to assassinate, assassination, etc., is both

French and English; and it is supposed we borrowed it from the French. But

that might not be the case, since both nations might have it from a common

original, as nobody pretends to assert it is a pure French, or even a Gaulish

word. Thus Mons. Menage acknowledges, that it came to the French from the

East, “ce mot nous est venu du Levant avec la chose." This author says,

Le Vieil de la Montagne, the Old Man of the Mountain, Prince of the

Arsacides, or Assassins and Bedins, fortifying himself in a castle of

difficult access, in the time of our expeditions to the Holy Land, collected

together a number of people, who engaged to kill whomsoever he pleased.

Hence, he adds, both the Italians and the French called those people

assassins that committed murders in cold blood. It seems, they were also

called Arsacides. Menage cites his authorities, but passing them by, I shall

content myself with giving you the words of one or two of our English

authors. Dr. Fuller says (" Hist, of the Holy War," p. 38), “These

assassins were a precise sect of Mahometans, and had in them the very spirit

of that poisonous superstition. They had some six cities, and were about

40,000 in number, living

near Antaradus in Syria. Over these was a chief master whom

they called the Old Man of the Mountains. At his command they would refuse no

pain or peril, but stab any prince, whom he appointed out to death - }

scorning not to find hands for his tongue, to perform

what he enjoined. At this day there are none of them extant,

being all, as it seemeth, slain by the Tartarians, anno 1237," etc.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4457) (tudalen 129)

|

Assassin. 129

Mr. Sale, in his preliminary discourse to the Koran, p. 246, gives the

following authentic account of them: “To the Karmatians, the Ismaelians of

Asia were very near of kin, if they were not a branch of them. For these, who

were also called al molahedah, or the impious, and, by the writers of the

history of the Holy Wars, assassins, agreed with the former in many respects;

such as their inveterate malice against those of other religions, and

especially the Mohammedan, their unlimited obedience to their prince, at

whose command they were ready for assassinations, or any other bloody or

dangerous enterprises; their pretended attachment to a certain Imam of the

house of Ali, etc. These Ismaelians, in the year 483, possessed themselves of

Jebal, in the Persian Irak, under the conduct of Hasan Sabah; and that prince

and his descendants enjoyed the same for 171 years, till the whole race of

them was destroyed by Holagu the Tartar." Whence it appears, that the

assassins were not Mohammedans, as Dr. Fuller suggests, but rather of a

religion set up in opposition to Islam, or that introduced by Mohammed. Both

authors, however, agree in their characters as to their being professed

bravo's, or murderers; and it appears from Matthew Paris in several places,

that the Oriental name of this people, as a nation or community, was that of

assassins. From the East it was brought to us, who were entirely unacquainted

with it, till after the era of the Crusades; and it has been now, for an age

or more, applied to persons of the like murderous disposition.

I am, yours, etc., T. Row.

[i 768, /. 464-]

To what Mr. Row has collected about the Assassins in your Magazine for last

July, you may, if you think fit, add what follows:

“The Batineans were profest Assassins, and are called in history Ishmaelians,

Hassassins, Assassinians, whence we have borrowed the word. Some say they

were originally Karmathians, whose conduct they closely followed. They formed

a kind of dynasty which lasted about 170 years. Their first prince was Hassan

Sabah, who established himself in Persian Irak, A. Heg. 483. Their chief

place of shelter was the castle of Almut. Historians have called their leader

the old man of the mountain, translating thus Sheik al Gebal, q. d. Lord of

Persian Irak, because Sheik signifies an.0A/ man, and Gebal, a mountain, and

Irak is very mountainous. Marigny's Hist, of the Arabians, iv. 128, note.

[See note 36.] H. D.

Beauty.

[1771, /. 166.]

Charles VII., King of France, having given his mistress, Agnes de Sorel, the

Castle of Beaute, she was thence called the Demoiselle de Beaute. This

introduced the term in France, and afterwards ia England. [See note 37.]

9

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4458) (tudalen 130)

|

130 Special Words.

Bast

[1784, Part I., p. 253.]

Your correspondent W. in your Magazine for December last, p. 1028, seems

desirous of knowing the meaning of the word BAST, in an Act of Parliament

made for punishing of wood-stealers, 15 Charles II. chap. 2, and supposes it

means the fruit of the tree, and to be derived from the word MAST; and your

other correspondents R. B. and A. in your Magazine for February, p. 106, both

imagine it may be derived from the word BASS, whereof mats used by gardeners

are made. Now I take the liberty to differ from both these opinions; and

having looked into Jacob's Law Dictionary, which I think the best expositor

of the words of an Act of Parliament, I find the word BASTON, and that it

signifies a staff or club; and as sticks to walk with are generally made of

young shoots, or scyons, the extracting whereof from plantations or coppices

of wood is very prejudicial, and great damage to the proprietor of such wood,

I therefore presume this statute might probably be made for the better

preventing such pilfering; and the constable is ordered to apprehend all

persons carrying away burthens or bundles of wood, underwood, poles, or young

trees, bark, or bast of any trees, etc.; and also to search the houses of

suspicious persons for such kind of things; and any persons buying such are

punishable.

Now it is natural enough to suppose that the word BAST, in this Act, is a

contraction of the word BASTON; for it is very common in the English language

for words of more than one syllable to be so contracted; and I am the more

inclined to think that is the case here; for that the taking of the fruit of

forest trees, or the mast of beech, is not an injury of such consequence as

to be the subject of an Act of Parliament.

The beech tree grows only in some particular parts of this kingdom, in woods,

and is there seldom mixed with other sorts: and I believe the lime tree is not

originally of this country, nor grows spontaneously in any part of it, that I

know of.

I am told that the bass-mats, used for packing goods, or for gardens, come

chiefly (if not wholly) from Russia, and perhaps may be made of the bark of

the lime, or some other tree growing in that country, but could by no means

be intended by this Act.

[See note 38.] Yours, etc., R. S.

Bum-fiddle.

[1775. P- 368.]

I have read with pleasure Mr. T. Row's ingenious explanations of many terms

whose derivation length of time has rendered obscure; but I was rather

disappointed in not finding among them the etymology of Bum-fiddle, a word

that is far from being obsolete, however

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4459) (tudalen 131)

|

Bum-fiddle. 131

arduous may be the task of investigating the origin of it. The learned author

of the “Commentary on the Laws of England" has clearly shown (b. i. c.

9, 8vo. edit., p. 346) that another word, to which the same monosyllable is

now usually prefixed, has suffered an alteration by the common people; for

that “bound-bailiff" was the original term: and possibly this may have

been the case in the word before mentioned, though I am not deeply enough

versed in antiquarian lore to discover the source of the corruption. Mr. Paul

Gemsege formerly transmitted to the public, through the channel of your

magazine, a curious disquisition on the favourite word and thing

"bumper," as also a second upon the terms "crowder" and

"crowdero;" and, as the instrument which is the subject of this

letter is undoubtedly a species of the crowdero, I am solicitous to know his

sentiments upon it. [See Gent. Mag. Library, “Manners and Customs," p.

157.] ANTIQUE.

Coccayne and the Cockneys.

[1838, Part //., pp. 596-602.]

We have fallen on a very dainty subject. We want to prove that the glorious

and song-renowned “land of Coccayne" is neither more nor less than the

land of Cookery, and that the Cockneys or Coccaneys derive their name from

thence, as the proper and legitimate natives of the said kingdom of Coccayne.

We think we shall be able to establish this connection between the land of

Coccayne and the Cockneys by many good and sufficient authorities, and, by so

doing, show the point and propriety of the appellation that has so long

fastened itself on our metropolitans, and refute those vulgar and erroneous

notions that are still afloat on the stream of Cockney chit-chat.

The etymology of the Latin word Coquo, to cook, from which, we verily believe,

the words Coccayne, Cockney, etc., are derived, is thus stated by Guichard in

his “Harmonie Etymologique des Langues," Paris, 1506: “Le verbe

Hebrai'que Goug signifie premierement coquere panes subter prunas." From

this root he supposes that the Greeks derived their ximw, misceo> to mix;

and the Latins their cogue, to cook. “Apres de COQUO, koken fut forme en

Flamen; kocken en Allemand; cucinareen. Italien; cozinare, cozer, en

Espagnol; cuire en Francais: cook en Anglais." So much for etymologies:

we shall see, anon, how critically they bear upon our friends the Cockneys.

The subject of cooker y, in all its branches, is one that we approach with

infinite respect and reverence. It hides its head among the clouds, while it

walks up and down on the earth. If we may believe so shrewd a mythologist as

Homer, the gods themselves, in the gorgeous palaces of Olympus, cultivated

this science of sciences before

92

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4460) (tudalen 132)

|

132 Special Words.

men were either born or thought of. The magnificent banquet at which Jove

himself presided, when the limping Vulcan acted the part of cup-bearer so

awkwardly as to fill the immortals with unextinguishable merriment, has

always been a favourite topic among epicures. Plato himself appears to have

entertained very savoury conceptions respecting the nectar and ambrosia once

served by Hebe and Ganymede; and indeed the very mention of such things is

enough, in Cockney dialect, “to make one's mouth water."

Among the Jews, and most of the ancient nations, so great was the respect

entertained for cookery, that official epulones, superintendents and

inspectors of their fasti, epulae, and dapes were appointed. In Rome they had

seven dignitaries of this kind, whose duty was to furnish banquets for

Jupiter and the other gods of his retinue. The sacrifice being over, the gods

were served as if they were able to eat, and, on their declining the offer,

the epulones very obligingly performed that function for them.

We know not how it is, but Epicures and Apicians have in all ages possessed

an extraordinary faculty of magnifying their office; Ude or Kitchiner, we

forget which, got into so lofty a rhapsody concerning the art and mystery of

cookery, as to call it the very mother of all moral, intellectual, social,

and political improvement. Their argument was, that men never reasoned

clearly and correctly on these abstract and metaphysical matters unless their

stomachs were in a prosperous condition, and well lined with culinary

blessings. As they had probably indulged in an extravagantly good dinner

before allowing their imagination so outrageous a swing, we shall make every

excuse for them which the case admits.

But seriously, and without a joke, the progress of cookery is one of the best

tests we have of the progress of civilization. What Dr. Johnson said of law

may with great propriety be applied to this subject. “Do you, Sir, presume to

deride that science which is the last effort of human genius working on human

experience?" Here, and here alone, reason and taste have gone hand in

hand, and the sublimest abstractions of Epicurus have been tested by no less

infallible a criterion than “Do you like it?"

Sir Humphry Davy appears to have caught a glimpse of this sublime theory in

one of his philosophic visions. When his emancipated spirit arrives at the

planet Saturn, which he imagines to be a much more respectable world than our

own, touching its ecclesiastical and civil polity, what does he discover?

why, Sir, he discovered that the whole surface of Saturn is strewed with

enormous culinary machines worked by steam and oxygen gas. Viands the most

exquisite that ever enchanted the olfactories of the ex-president, diffused

their delicious effluvia through the whole atmosphere of the planet. They

were cooked by a chemistry, or rather an alchemy, which defied the most

critical analysis of the Royal Institution, and altogether made

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4461) (tudalen 133)

|

Coccayne and the Cockneys. 133

Sir Humphry feel, if he never felt so before, like a thorough-bred glutton

Epicuri de grege porcus.

The inhabitants of Saturn, who were shaped more like elephants than anything

else, were disporting themselves on the wing between the mainland and the

ring. This exercise they invariably took in order to give themselves a

constitutional appetiser or whet for the keener relish of their dinner; and,

according to the said president, our best authority on the subject, these

Saturnites, if they spent not their time like ingenious Athenians in seeing

or hearing some new thing, contrived to pass it in the more agreeable or at

least substantial employment of tasting and devouring new dishes. So much for

the cookery of the stars.

Of the cookery of the Oriental world we have some very transcendental and

magnificent speculations, derived from the authority of the Koran, the

Arabian Nights, and the very piquant stories of travellers, which we always

swallow aim grano salt's, with a little salt, which we find assists their

digestion, and saves us from that highly fashionable complaint dyspepsia.

But attend to Mahomet a moment: for his description of cookery in Paradise

is, as Sir John Falstatf says, “worth the listening to." In the

entertainment of the blessed on their admission to Paradise, thus speaks the

Prophet: The whole earth will then be as one loaf of bread, and for meat they

shall have the ox Balam and the fish Nun, the lobes of whose livers will

suffice seventy thousand men. From this feast every one will be dismissed to

the mansion assigned him, where he will have such a share of felicity as is

proportionate to his merit, but vastly exceeding comprehension or

computation, since the very meanest in Paradise will have 80,000 servants, 72

wives of the girls of Paradise, beside the wives he had in this world, and a

tent erected for him of pearls, jacinths, and emeralds of a very large

extent. There he will he waited on by 300 attendants while he eats, and shall

be served in dishes of gold, whereof 300 shall be set before him at once,

containing each a different kind of food, the last morsel of which will be as

grateful as the first, and will also be supplied with as many sorts of

liquors in vessels of the same metal; and, to complete the entertainment,

there will be no want of wine, which, though forbidden in this life, will yet

be freely allowed in the next without danger, since the wine of Paradise will

never inebriate though you drink it for ever.

But all these glories, as Sale observes, will be eclipsed by the ravishing

girls of Paradise, called Houris, from their large black eyes, Hur al oyun,

the enjoyment of whose company will be a principal felicity of the faithful.

These are not created of clay, as mortal women are, but of pure musk, and

their bodies are odoriferous as frankincense; being free from all defects and

inconveniences incident to the sex, of the strictest modesty, and secluded

from public view in

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4462) (tudalen 134)

|

134 Special Words.

pavilions of hollow pearls, so large that

one of them will measure sixty miles long and as many broad.

Thus the bold and dazzling imagination of the East has ever delighted to draw

analogies and correspondences between the spiritual and physical economies of

nature, which Milton seems to have dreamed of in his description of Paradise,

where he says,

“For earth hath this variety from heaven Of pleasure situate in hill and

dale."

Perhaps, however, there is more analogy than we suppose, as the soundest and

gravest commentators on Scripture, like Grotius, have adopted this idea,

which has been carried to so great a length by the Swedenborgians.

Grotius, whom of all men we love best to imitate, regarding him as the

greatest light that ever yet scattered the clouds of ignorance and discord

that still hover around us, makes the tree of knowledge in the earthly

Paradise no less dainty and delectable than the immortal palms of Mahomet's

elysium. In fact, he supposes the fruit was excessively nice, and that Eve,

with due reverence be it spoken, was a little epicure, or at least a little

of an epicure. For thus she speaks in the Adamus Exul, which is the parent of

Paradise Lost:

“O sweet, sweet apple! how thy glittering store Dazzles try eyes; its

dream-like, exquisite scent Fills all my sense; would I could lay aside All

fear, that trembling folly, and enjoy The elysium of the fruit, and learn at

once Its mystery of bliss."

It is necessary to observe that in the East, cookery very early divided

itself into two branches, the science and the art; one was the learned,

occult, esoteric, initiated cookery of the physicians and philosophers, now

called dietetics; the other was that vulgar, but exceedingly edifying, art,

which, though comparatively undiscriminating, is far more satisfactorv, and

has consequently almost superseded the other in popular esteem.

An old writer of the sth century, no less a man than St. Ambrose, was highly

indignant with these medical dietetics, which he evidently considers the

worst dep tment of cookery. "The precepts of physic," says he,

"are contrary to divine living, for they call men from fasting, suffer

them not to watch, seduce them from opportunities of meditation. They who

give themselves up to physicians deny themselves to themselves." And St.

Bernard on the Canticles thus asserts -. “Hippocrates and Socrates teach how

to save souls in health in this world; Christ and his disciples how to save

them for the next; which of the two will you have to be your masters? He

makes himself noted who, in his disputations, teaches how such a thing hurts

the eyes, this the head, that the stomach; pulse are

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4463) (tudalen 135)

|

Coccayne and the Cockneys. 135

windy, cheese offends the stomach, milk hurts the head, water the lungs;

whence it happens that in all the rivers, fields, gardens, and markets, there

is scarce to be any thing fitting for a man to eat."

From these passages it is evident that the dietic and therapeutic system of

physic by no means pleased the Fathers or the monks; and, indeed, it must

have been discordant to the rules and regulations of good Catholics in

general.

Cornelius Agrippa, whom we take to have been nearly the greatest man of his

age, confirms the same censure on the dietetic doctors, and his remarks apply

patly enough to Dr. Abernethy and his school, in the nineteenth century.

"These doctors," says Agrippa, "command, forbid, curse, and

discommend the meats and drinks that God has. created; framing rules of diet

difficult to be observed, and those morsels which they forbid others to taste

of they themselves (as hogs eat acorns) greedily devour. And those laws of

living which they prescribe to others, they themselves altogether neglect or

contemn. For, should they live according to their own rules, they would run

no small hazard of their health; and, should they permit their patients to

live after their own examples, they would altogether lose their

profits."

“But grant," continues Agrippa (who never lost an opportunity of giving

the monks a dry rap over the knuckles, for taking which liberty he was often

within an ace of being roasted for a necromancer), “that these rules of the

doctors apply to the monks, for whom, perhaps, it is not needful to take so

much care of their healths as of their professions, yet the variety of dishes

and feasts may not be unlawful for civil men to use, with consideration of

their health. The first the art of dieting performs, the second the art of

cookery, being the dressing and ordering of victuals. For which reason Plato

calls it the ' flatteress of physic,' and many account it a part of dietary

physic, though Pliny and Seneca, and the whole throng of other physicians,

confess that manifold diseases proceed from the variety of costly food."

Now Asia, and the land of the East, is the first land of Coccayne, or country

of good feeding, that we read of. The Asiatics were so intemperate and

luxurious in their feeding, that they were known by the surname of Asotse, or

Gluttons, or, more properly translated, Cockneys. If we were to make

inquiries of the board of East India Directors, ex-nabobs, etc., they would

very probably inform us that the Asiatics have not yet forfeited their claim

to this honourable epithet; or, if their tongues preserved silence, their

livers would answer for them. For these livers of ours are very

discriminating logicians, and easily detect the sophistry contained in that

noted verse,

“He that lives a good life is sure to live well."

It was from the East, the earliest land of Coccayne, that Greece learnt the

great lesson of Cockneyship, and became the rival of her

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4464) (tudalen 136)

|

136 Special Words.

instructress. If the soldiers of Greece

conquered Persia, the cooks of Persia conquered Greece, and exchange is no

robbery. We shall not expatiate on Grecian cookery, lest we should so debauch

our souls with its manifold luxuries as to become incapable of travelling

into the next great kingdom of Coccayne, “the revel of the earth, the mask of

Italy."

Asia and Greece both revenged themselves on their Roman conquerors, by making

them the victims of triumphant luxury. Then Italy, in her turn, became the

veritable land of Coccayne; and of her feast monarchs partook and deemed

their dignity increased; and the stern Romans at length became the most

unparalleled Cockneys under the sun.

Thus we read in Livy'(as an old writer well observes), after the conquest of

Asia and Greece, foreign luxury first entered Rome, and then the Roman people

began to make sumptuous banquets. Then was a cook the most useful slave that

could be, and began to be much esteemed and valued, and, all bedabbled with

broth, and bedaubed with soot, was welcomed out of the kitchen into the

schools; and that which was before accounted as a vile slavery, was honoured

as an art whose chiefest care is only to search out everywhere the

provocatives of appetite, and study in all places for dainties to satisfy a

most profound gluttony; abundance of which Gellius cites out of Varro, as the

peacock from Samos, the Phrygian turkey, cranes from Melos, Ambracian kids,

the Tartesian mullet, trouts from PesseMuntium, Tarentine oysters, crabs from

Chios, Tatian nuts, Egyptian dates, and Iberian chesnuts. All which enormous

bills of fare were found out for the wicked wantonness of luxury and

gluttony.

But the glory and fame of this art, Apicius, above all others, claimed to

himself: from him, as Septimus Florus witnesses, there arose a certain sect

of cooks that were called Apicians, propagated, as it were, in imitation of

the philosophers, of whom thus Seneca has written: “Apicius (says he) lived

in our age; who in that city out of which philosophers were banished as

corrupters of youth, professing the art of cookery, hath infected the whole

rising generation with the most astounding luxuriousness."

Pliny calls this Apicius the gulf and barathrum of all youth. At length so

many subjects of taste, so many provocatives of luxury, so many varieties of

dainties were invented by these Apicians, that it was thought requisite to

restrain the luxury of the kitchen. Hence all those ancient sumptuary laws.

Lucius Flaccus, and his colleague censors, put Duronius out of the Senate,

for that, as a tribune of the people, he went about to abrogate a law made

against the excessive prodigality of feasts. In defence whereof, how

impudently Duronius ascended the pulpit of orations: “There are bridles (said

he) put into your mouths, most noble senators, in no wise to be endured. Ye

are bound and fettered with the bitter chains of servitude. Here

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4465) (tudalen 137)

|

Coccayne and the Cockneys. 137

is an old antiquated sumptuary law which commands us to be frugal: let us

abrogate such a demand, deformed with the rust of ghastly antiquity; for to

what purpose have we liberty, if it be not lawful for them that will to kill

themselves with luxury?"

At length the character of Italy, as the land of Coccayne and the empire of

good living, got sadly impaired by the ravages of Huns, Goths, Visigoths,

Saracens, and rascally barbarians of all kinds, that came down like a

darksome cloud of locusts, and demolished her loaves and fishes before she

could say Jack Robinson. In fact, Virgil's vision of the banquet and the

harpies was most painfully realized in his dear Italia, which still

reverences him as a wizard and arch magician, on account of such prophetical

allusions sprinkled through his works. As we do not, however, give much

credit to the Sortes Virgilianae, we shall say no more about it.

Thus the ever memorable land of Coccayne was for some time overwhelmed by the

invasion of barbarism, not to say cannibalism, which is the very basest kind

of cookery we are aware of. Dear land of Coccayne, for centuries thy very

existence was a problem: the disciples of Epicurus, with a portentous

elongation of physiognomy, went seeking thee as carefully as Ceres sought

Proserpine, and, alas! found only that you were not to be found.

Sometimes they seemed to recover a glimpse of thy august vision in the states

of Italy, but they only aggravated the disappointment of the surviving

Cockneys, who then wandered, like the Jews or the Gypsies, up and down the

earth, yet could find no country like their own. Then was the land of

Coccayne likened unto the land of Utopia, “that place called No Place,"

or the island of Atalantes, or the land of Limbo.

At length, however, the great vision of Coccayne once more gladdened the

hearts of disconsolate Cockneys. Her first appearance was at Florence, then

at Venice, then at Palma. All these became celebrated in turn as the

veritable Coccayne; resuscitated, as it were, from the grave for the benefit

of all good fellows. As the empire of Coccayne advanced, savagery and

barbarism retired, and civilization and good-humour resumed their legitimate

ascendancy.

The empire of Coccayne then travelled west, and was long preeminent in

France. France and Paris are lauded as the land of Coccayne in numberless old

songs, and the French were entitled Coccainees par excellence.

But the empire of Coccaygne did not confine itself to France; it travelled

over to Great Britain, and took up its residence in London, which has long

appropriated the title to herself, with a most commendable enthusiasm. The

epithet Cockney has for ages so fastened itself on the inhabitants of oar

English Babylon, that not all the steam-engines in the country could now

explode it. In fact, it sits so

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4466) (tudalen 138)

|

138 Special Words.

happily on the natives of “the great

metropolis," that nothing would console us for the loss of it.

Now let us confirm our statements by a few authorities; for we entirely agree

with our legal brethren, that assertions are not worth a crack without

confirmation and proof to back them withall.

In Toone's “Etymological Dictionary “(a very useful little book), we find the

following: “In a mock heroic poem in the Sicilian dialect, published at

Palermo, 1674, a description is given of Palma, as the Citta di Cuccagna; and

Boileau calls Paris unpais decoccaigne, representing it as a country of

dainties; which seems to have been the meaning of the word as understood by

the French." In England, no precise time can be ascertained as to its

first introduction. The earliest poem in which it is mentioned is a very

ancient one in the Normanno-Saxon dialect:

“Far in sea by West Spayne Is a lond yhote Cocayng."

In a very curious poem called the “Tournement of Tottenham," said to be

written in the reign of Edward III., the word Cokeney is used, but whether as

applied to a cook or a dish is a matter of conjecture:

“At that feast they were served in rich aray, Every five and five had a

cokenay."

Which reminds us of the Welshman's boast:

“Nine cooks at least in Wales one wedding sees."

In Nares's “Glossary “are the following remarks: “What this word Cockney

means, is well known how it is derived, there is much dispute. The etymology

seems most probable which derives it from cookery. Le pais de cocagne, in

French, means a country of good cheer; in old French, coquaine. Cocagna, in

Italian, has the same mending. Both might be derived from coquina. This

famous country, if it could be found, is described as a region 'where the

hills were made of sugar-candy,' and the loaves ran down the hills crying, '

Come, eat me!' “

It is spoken of by Balthazar Bonifacius, who says, “Regio qucedam est, quam

Cucaniam vocant ex abundantia panis qui atca Illyrice dicitur." “There

is a certain region called Cocagne, from the abundance of bread, which the

Illyrians denominate cuca, or cake." In this place, he says, “rorabit bucceis,

pluet pultibus, ninget laganis, et grandinabit placentis:" which we thus

translate “it rains puddings, drizzles sausages, snows pancakes, and hails

apple-dumplings."

The Cockney spoken of by Shakespeare seems to have been a cook, as she was

making a pie. “Cry to it, nuncle, as the Cockney did to the eels when she put

them i' the paste alive." Yet it appears to denote mere simplicity;

since the fool adds, "'Twas her brother that in pure kindness to his

horse buttered his hay,' [King

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4467) (tudalen 139)

|

Coccayne and the Cockneys. 139

Lear, Act ii., sc. iv.] Some lines in Camden's “Remains “seem to make Cockney

a name for London as well as for its citizens. [See note 39.]

In the “Cyclopedia Metropolitana," we find the following under the word:

“Dr. Thomas Henshaw, sagaciously, as he is wont (Skinner observes), derives

Cockney from the French accoquina, to wax lazy, become idle, and grow

slothful as a beggar."

The passages brought in illustration are these:

“And when this jape is told another day, I shall be holden a daff cockanay; I

will arise and auntre it, by my fay; Unhardy is unsdy, as men say."

Chaucer.

“I speak not in dispraise of the falcons, but of them that keep them like

Cokeneys." Sir Thos. Elliot. [See note 40.]

“Phillip he smiled in his sleeve, And hopeth more to smile, Willing this

Cockney to intrap

With this same merry wyle." Drant's Horace. 44 And with a valiant hand

from off

His neck his gorget tear, Of that same Cocknie Phrygian knight, And drench in

dust his hair." Phaer.

14 1 meet with a double sense of this word

Cockney, some taking it for

“ist. One coaked or cockered, made a wanton or nestle-cock of, delicately

bred and brought up, so that when grown men or women, they can endure no

hardship nor comport with painstaking.

"andly. One utterly ignorant of husbandry and housewifery, such as is

practised in the country, so that they may be persuaded anything about rural

commodities, and the original thereof; and the tale of the citizen's son, who

knew not the language of a cock, but called it neighing, is commonly

known," Fuller's “Worthies."

"Some again are on the other extreme, and draw this mischief on their

heads by too ceremonious and strict diet, being over precise, Cockney like,

and curious in their observation of meals." Burton's “Anat. of

Melancholy."

"In these days," says old Minshew, in his admirable dictionary,

"we may change the term cocknays into Apricocks, in Latin pracocia, for

the suddenness of their wits , whereof cometh our English word pnncockes, for

a ripe-headed young boy."

To conclude, the empire of Coccayne has been extended even to Scotland , for

the land of Coccayne, and the land of Cakes, are essentially and

etymologically the same. For cake is derived from the Latin coquere, and the

Teutonic kuchen or kochen, to cook- How well Scotland is entitled to this

honourable name, will be acknowledged by those who have tasted her

hospitalities. So that they who are called Sawnies, because of their frequent

delivery of wise saws, are no less entitled to the luxurious appellation of

Cockneys. The Scotchman, therefore, resembles A nacreon's grasshopper:

“Voluptuous, but wise withall, Epicurean animal." Cowley's Trans.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4468) (tudalen 140)

|

140 Special Words.

Cock-loft.

[1858, Part II., p. 322.]

Antony Wood, in using this word, writes cockle-loft; which would seem to

point to the origin of the name from cockle, or darnel; the cock-loft of a

barn being the place where the inferior products of the field were kept.

Country Dance.

[1758. pp> i73> 174.]

Truth is a thing so sacred with me, and a right conception of things so

valuable in my eye, that I always think it worth while to correct a popular

mistake, tho' it be of the most trivial kind Now, sir, we have a species of

dancing amongst us which is commonly called country dancing, and so it is

written; by which we are led to imagine that it is a rustic way of dancing

borrowed from the country people or peasants; and this, I suppose, is

generally taken to be the meaning of it. But this, sir, is not the case, for

as our dances in general come from France, so does the country dance, which

is a manifest corruption of the French contredansef where a number of

persons, placing themselves opposite one to another, begin a figure. This now

explains an expression we meet with in our old country dance books, “long ways

as many as will;" as our present English country dances are all in that

manner, this direction seems to be very absurd, and superfluous; but if you

have recourse to the original of these dances, and will but remember that the

performers stood up opposite one to another in various figures, as the dance

might require, you will instantly be sensible, that that expression has a

sensible meaning in it, and is very proper and significant, as it directs a

method or form different from others that might be in a square or any other

figure.

Yours, etc., PAUL GEMSAGE.

Curries.

[1791, Part I., p. 126.]

In your vol. lx., p. 538, in the review of Mr. Pennant's "London,"

some doubt seems to have been entertained by the writer of that article both

as to the orthography and the meaning of the term curries. In the county of

Norfolk, however, or at least in the neighbourhood of Great Yarmouth, it is

constantly made use of to signify a smaller kind of two-wheeled cart, drawn

usually by one horse, and is derived undoubtedly, witli the word curricle (in

fashionable use for a more elegant kind of carriage), from the Latin verb

curro, in allusion to their velocity and lightness.

* Marshall Bassompierre, speaking of his dancing country dances here in

England in the time of K. Chas. 1., writes it expressly contredaiises.

t>ee his Memoiis, torn, iii., p. 307.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4469) (tudalen 141)

|

14*

There is another term also in use, and I believe peculiarly so, in that

county, namely, sluss or shish, to express the mire of the highway in its

most liquid state; which word also, arbitrary and provincial as it may

appear, is surely a derivative; not indeed from the Latin, like the other,

but (as it struck me on a perusal of Mr. Malone's “Historical Account of the

English Stage," prefixed to his edition of Shakspeare, lately published),

from the language of our forefathers of this island, and that not in vulgar

usage only, but poetic. In a quotation of Mr. Malone's from the “Mystery of

the Deluge," exhibited ,by the Dyers' Company, at Chester, above 450

years ago, in the opening speech, in which, besides other matter, the

Almighty instructs Noah how to frame and finish the Ark, are the following

lines:

“Litill chambers therein thou make,

And binding slytche also thou take,

Within and without ney thou slake

To anoynte yt “

Where by slytche is evidently intended slime, or mire, or slush, to be

applied to the fabrick of the Ark, for the purpose of closing the joints or

filling up all cracks and crevices to the exclusion of wind and water. G.

Dandy and Dandyprat.

[1819, Part II., pp. 7, 8.]

The word Dandipart, or Dandiprat, has, we believe, not been well denned by

any author, otherwise than by way of contempt and ridicule; and the term

Dandy, on the same principle, at the present day, is applied to a certain set

of men not unlike those formerly denominated Fribbles, who, instead of

supporting the dignity and manliness of their own sex, incline to the

delicacy and manners of a female. But from what source the word Dandy is

derived seems hitherto uncertain.

That Dandy and Dandyprat meant a term of reproach and ridicule, as abovesaid,

we have sufficient authority for. In Cotgrave's Dictionary (1650), it is

defined by Manche d'Estille handle of a currycomb, slender little fellow, or

dwarf.

Torriano, in his Italian Dictionary, construes Dandipart by Nani, or

Homiccnalo, a dwarf, pretty little man, or mannikin. Johnson merely says that

Dandipart means a little fellow, urchin; a word sometimes used in fondness,

sometimes contempt; and derives it from Dandin, a noddy, or ninny.

That the word means something diminutive is clear, from a child's book of

nonsensical verses, out of date many years since; one of which begins,

“Little Jack Dandiprat was my first suitor," etc. And again,

"Spicky spandy, Jacky Dandy," etc. [See note 41.] But, independent

of size, the word appears to define something very slender; for, in Bulwer's

"Artificial Changeling" 1653 [see note 42],

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4470) (tudalen 142)

|

142 Special Words.

in one of the complimentary sets of verses to the author, after noticing

various distortions of the human figure, he mentions one having

“Eares of so huge a compasse, and broad eyes, As men were swine, and tura'd

to owlebies."

And, in contrast:

“Sometimes with lacings and with swaiths so strait, For want of space we have

a Dandiprat."

And again:

“Sir Jeffries Babil, dilling petite A peccadillo of Barnabie's night, Things

so pucil and small, the statute wise Exempt from coupling, being under

size."

And further, we find the word used for something of little or no value, in a

dialogue between Comen Secretary and Jelowsy (see Beloe's Anecdotes, vol. i.,

p. 890), where Secretary says:

“Yes, but take heede by the pryce ye have no losse. A mode merchaunt, that

wyll gyve v marke for a goose. Beware a rolling ey, which waverynge thought

make that, And for such stuffe passe not a Dandy Pratt."

But to the purport of this letter, which is principally to inquire whence the

word Dandiprat or Dandipart has origin. We are told, in Camden's

“Remains," concerning Great Britain (1636), p. 188, that “King Henry the

Seventh stamped a small coin called 'Dandiprat,' and first I read coined

Shillings."

Leake, also, in his “Historical Account of English Monies" (1748), p.

182, mentions the same; and the definition of the word in Bailey's Dictionary

is, “a small coin made by Henry the Seventh;" but in the reign of that

Monarch we do not find mention of any such thing, unless it be possible that

the farthing of this reign, in Snelling's "Silver Coins," Plate

II., fig. 43, being very minute, might be so nicknamed.

I have therefore, Mr. Urban, troubled you with the above, in hopes that some

of your correspondents may have it in their power to inform us from what

source the words Dandy and Dandiprat may have originated, and if from a coin,

as above hinted, what it was, and whether it had rise in the reign of King

Henry the Seventh, or in that of any other of the Kings of England. [See note

43.]

Yours, etc., J. L.

Drunkenness.

[1770, //. 559, 56o.]

Perhaps nothing is a stronger proof of the general infelicity of life, than

the propensity of mankind in all countries and situations to drunkenness.

Drunkenness does nothing more than suspend the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4471) (tudalen 143)

|

Drunkenness. 143

sense of our real condition for a short

interval; yet this delusion is so sweet, that it is indulged at the risk of

fortune, health, life, and reputation. To drink the waters of oblivion, can

never be the wish of the happy; yet even the savages of America and Africa

will sell their wives and children to purchase the pernicious Lethe of art,

which therefore they appear to desire with no less ardour than the

inhabitants of London, where the acquisition of happiness may reasonably be

supposed to be more difficult, as it depends upon the gratification of wants

infinitely multiplied, and the possession of things for which all are

competitors, and which few can obtain. If in the general estimation the

substitution of frenzy for reason is desirable, it follows, that in the

general estimation it is advantageous to exchange what is, for what is not.

This, however, like most other gratifications, has been stigmatized as

immoral, and indeed with much better reason than many, for upon the whole it

certainly lessens the good of life, however small, and increases the evil,

however great. We have therefore contrived a great variety of names and

phrases, most of them whimsical and ludicrous, to veil the turpitude of what

is pleasing in itself, and generally connected with reciprocations, if not of

friendship, yet of the lesser duties and endearments of society.

I believe few people are aware how far this has been carried, or have any

notion that the simple idea of having drunk too much liquor, is expressed in

near FOURSCORE different ways. I send you a list of them for the amusement of

your readers in your Christmas Magazine.

I am, Sir, your humble Servant,

T. NORWORTH.

To express the condition of an Honest Fellow, and no Flincher, under the

Effects of good Fellowship, it is said that he is

1 Drunk,

2 Intoxicated,

3 Fuddled,

4 Flustered,

5 Rocky,

6 Tipsey,

7 Merry,

8 Half seas over,

9 As great as a Lord,

10 In for it,

11 Happy,

1 2 Bouzey,

1 3 Top-heavy,

14 Chuck full,

15 Hocky,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4472) (tudalen 144)

|

144 Special Words.

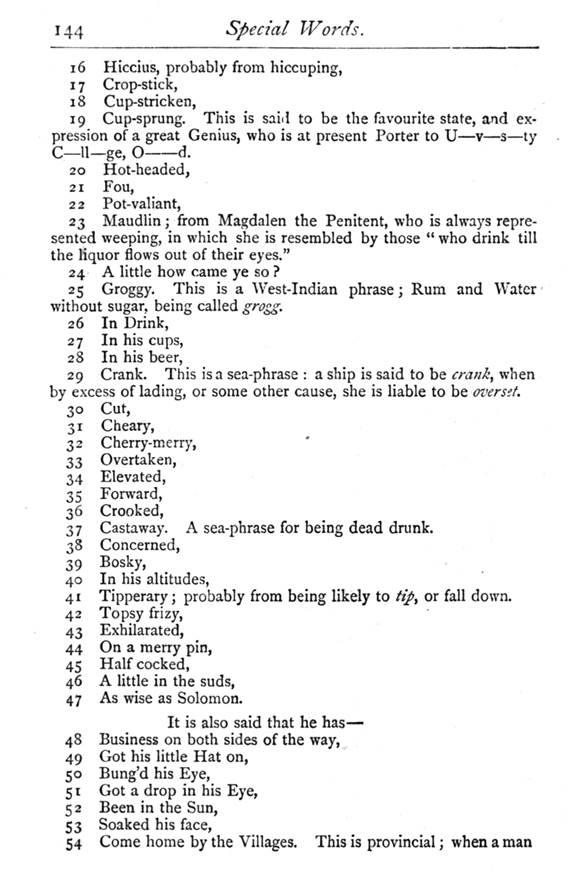

1 6 Hiccius, probably from hiccuping,

1 7 Crop-stick,

18 Cup-stricken,

19 Cup-sprung. This is said to be the favourite state, and expression of a

great Genius, who is at present Porter to U v s ty C 11 ge, O d.

20 Hot-headed,

21 Fou,

22 Pot-valiant,

23 Maudlin; from Magdalen the Penitent, who is always represented weeping, in

which she is resembled by those “who drink till the liquor flows out of their

eyes."

24 A little how came ye so?

25 Groggy. This is a West-Indian phrase; Rum and Water without sugar, being

called grogg.

26 In Drink,

27 In his cups,

28 In his beer,

29 Crank. This is a sea-phrase: a ship is said to be crank, when by excess of

lading, or some other cause, she is liable to be overstt.

30 Cut,

31 Cheary,

32 Cherry-merry,

33 Overtaken,

34 Elevated,

35 Forward,

36 Crooked,

37 Castaway. A sea-phrase for being dead drunk.

38 Concerned,

39 Bosky,

40 In his altitudes,

41 Tipperary; probably from being likely to tip> or fall down.

42 Topsy frizy,

43 Exhilarated,

44 On a merry pin,

45 Half cocked,

46 A little in the suds,

47 As wise as Solomon.

It is also said that he has

48 Business on both sides of the way,

49 Got his little Hat on,

50 Bung'd his Eye,

5 1 Got a drop in his Eye,

52 Been in the Sun,

53 Soaked his face,

54 Come home by the Villages. This is provincial; when a man

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4473) (tudalen 145)

|

Drunkenness. 145

comes home by the fields, he meets nobody,

consequently is sober; when he comes home by the Villages he calls first at

one house, then at another, and drinks at all.

55 Got a spur in his head. This is said by brother-jockies of each other.

56 Got a crumb in his beard,

57 Had a little,

58 Had enough,

59 Got more than he can carry,

60 Got his beer on board,

6 1 Got glass eyes,

62 Been among the Philistines. A pun upon the word _///.

63 Lost his leggs,

64 Been in a storm. This is a sea-phrase for] being less than dead drunk.

65 Been in the Crown Office. A pun upon the word crown used for the head.

66 Got his Night Cap on,

67 Got his Skin full,

68 Got his Dose,

69 Had a Cup too much.

Besides these modes of expressing drunkenness by what a man is, what he has,

and what he has had, the following express it, by what he does

70 Clips the King's English, i.e., Does not speak plain.

71 Sees double,

72 Reels,

73 Heels and sets. A sea-phrase used of a boat in a rough sea.

74 Heels a little,

75 Shews his Hob-nails. This is a provincial phrase for being so drunk as not

to be able to stand, so that the nails at the bottom of the shoe are seen.

76 Looks as if he could not help it,

77 Crooks his Elbow,

78 Goes over the Tops of Trees. This is provincial, and alludes to the

unequal pace of a drunken man, like that of stepping from a high tree to a

low one, and from a low one to a high one.

To these must be added one phrase that expresses drunkenness by what a man

cannot do; it is said by the sons of science at Oxford, of a man in ebrious

circumstances,

79 That he cannot sport a right line.

I shall not mention the additions that have been made by way of illustration

to several of the terms in this list, although, taken together, they may be

considered as separate phrases; among these are

VOL. II. 1

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4474) (tudalen 146)

|

146 Special Words.

I

2

3

4

As As As As

drunk drunk drunk drunk

as as as as

a Devil, a Piper, an Owl, David's Sow,

5 6

7 8

As As As As

drunk as a fuddled as merry as a happy as a

Lord, an Ape, Grigg, King.

Earing.

[I75S. PP. 212, 213.]

“And yet there are five years, in the which there shall be neither earing nor

harvest." GEN. xlvi. 6.

This word earing occurs in other places of Scripture, but I have pitched upon

this, because this chapter, being twice read as a Sunday lesson in the

publick service of the Church, this passage 'tis presumed may be the best

known. The word is grown obsolete, and partly through disuse, but chiefly

from its being so like in sound, and its present orthography, to the ear or

spica of the corn, I have observed the sense of it to be sometimes mistaken

by writers, from whence I conclude that others who are unacquainted with the

learned languages must consequently be liable to the same error. Thus the

Earl of Monmouth, in his translation of “Boccalini," p. IT, says, “The

plowers of poetry have seen their fields make a beautiful show in the spring

of their age, and had good reason to expect a rich harvest, but when, in the

beginning of July, the season of earing began, they saw their sweat and

labours dissolve all into leaves and flowers;" where he evidently means

by the season of earing, the time when the corn runs into the ear, in

opposition to the time of ploughing. Another mistake concerning the sense of

this word, incurred by Mr. Theobald, will be mentioned below.

But to ear signifies to plough, and is always used in that sense by our old

writers, so Isaiah xxx. 24, “The oxen likewise, and the young asses that ear

the ground, shall eat clean provender," etc. So Speed, p. 416, says the

Danes "grieved the poore English, whose service they employed to eare

and till the ground, whilst they themselves sat idle, and eate the fruit of

their paines." Dr. Wicliffe, in his New Testament (Luke xvii. 7), writes,

“But who of you hath a servaunt cringe," where the vulgate version, from

whence the Dr. made his translation, has arantem. The sense is clear, and the

word is evidently the Anglo-Saxon epian, which signifies to plough, and is

plainly derived from the Latin aro, and what we now call arable land,

Greenway, in his translation of Tacitus's account of Germany, calls earable

land, from the Latin arabalis. In this text, therefore, earing and harvest

are opposed to one another, as two different extremes, just as seed-time and

harvest are (Genesis viii. 22), to the former of which it manifestly answers,

and the sense consequently is, "in the which there shall neither be

ploughing nor harvest."

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4475) (tudalen 147)

|

Earing. 147

[1770, pp. 161, 162.]

As your magazine is calculated to convey useful knowledge as well as

entertainment (prodesse et delectare), be so good as to insert the following

lines in your next vehicle of intelligence.

A learned Doctor of divinity being asked a few days ago, “What is the meaning

of that expression in Exodus xxxiv. 21, in earing-time, and harvest thou

shalt rest?" replied “That he supposed by earing-time, is meant the time

when the corn begins to appear in the ear." Now lest any of the readers

of their Bible be mislead by a wrong interpretation, please to inform them

that the original word, bHH charish, is in other passages of Scripture

rendered to plow; Psalm cxxix. 3, “The plowers plowed upon my back."

This will help us to understand that text in i Samuel viii. 12, “He will set

them to ear his ground^ and to reap his harvest; and this will help us also

to rectify a mistake in the eighth addition of Bailey's “Dictionary," in

which earing time is explained to be harvest; notwithstanding he says just

before, very rightly, that to Ear, or Are, or Arare, signifies to till, or

plow the ground." {See post, p. 185.]

R. W.

Firm.

[1784, Part I., p. 164.]

Please to inform your Nottinghamshire Correspondent, who desires to know the

etymology of the vjfx&jfirm, that it is originally Spanish and perhaps is

no where else used in the sense ascribed to it but by, them and the English.

It is obvious that language, in its progress, admits of some variation in its

meaning, and is either enlarged or contracted by accident. The word, in the

original, signifies nothing more than subscription, or signing. So

Nebrissensis explains the word: Firma de escritura, subscript, signatio.

Firma escritura, subscribo, signo. In this sense it is constantly used by

Cervantes, and the several places are pointed out in the first indice of the

edition of 1781, and is explained in the “Anotaciones." Antwerp having

been for a long time under the dominion of the Spaniards, and a great staple

of commerce, it is natural to suppose that we may have adopted it from

thence. As it may be proper for a trading company to have one signature, it

may have been confined to such. The Portuguese affix the same meaning to the

word with their neighbours. But it occurs not in the Italian or French.

Franciosini, in his “Dictionary," renders Firma, la Sottoscrizione di

propria mano: Sobrino, Firma, signature; Firmar, signer, souscrire.

Yours, etc., A. B.

10 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4476) (tudalen 148)

|

148 Special Words.

Foy.

[1832, Part II., /. 194.]

M H. observes, “Both at Margate and at Ramsgate, there are public-houses

known by the sign of the Foy Boat, the meaning of which I was unable to

obtain from any person I there conversed with. No such word occurs in

Johnson, Ash, or Todd. In Ash's “Dictionary “there is the word fey, which he

explains as being derived from the Dutch veghen, to cleanse a ditch of mud.

The house appears to be the rendezvous of pilots; does it therefore mean

Feeboat, that is, the sum paid to pilots for their assistance to vessels in

distress?"

[1832, Part II., p. 290.]

I am induced to trouble you with the present communication, in consequence of

the observations of M. H. in your last Magazine, p. 194. The word foy is in

common use in the Northern counties of England, and also in Scotland. It

denotes an entertainment given to a friend or acquaintance about to leave his

home, or any particular place of residence. Those who are attached to him

assemble to set his foy; that is, to drink his health, or to partake of a

supper or other treat. Kilian, in his “Etymologicum Teutonics Linguse,"

very correctly defines the term. He interprets voye, "foye," as

signifying “Vinum profectitium symposium vise causa;" and derives the

word from the French voye, or way. It is not unusual for the owners of a

fishing-vessel to give a supper, called a foy, to the crew of the season.

Hence the sign of the Foy Boat, inquired after by your correspondent.

JOHN TROTTER BROCKETT.

Cornubiensis says that “the Foy Boat means nothing more than the passage-boat

to Fowey in Cornwall “(pronounced Foy}; but as our correspondent has given us

no proof that passage-boats between Fowey and Margate ever existed, we are

afraid he has been misled by enthusiasm for the quondam greatness of his

native county. In Dyche's Dictionary," the word foy is explained, as “a

treat given by a person to his friends or acquaintance, upon his change of,

or bettering his station in life, removing to a new habitation, going or

setting out upon a journey, putting on new clothes," etc. A

correspondent, therefore, suggests that “a Foy Boat may have been one given

originally to a pilot for uncommon or skilful exertions in some dreadful

storm now forgotten." According to Forby's "Vocabulary of East

Anglia,"yfry is the term applied to the “supper given by the owners of a

fishing-vessel, at Yarmouth, to the crew in the beginning of the season."

The word is probably derived from the French word foyer, the hearth or

hospitable fireside.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4477) (tudalen 149)

|

Foy. 149

[1833, Part L, p. 386.]

J. G. N. remarks, "Your correspondents in Oct. Mag., p. 290, appear to

have correctly explained the word foy; but not precisely the compound Foy

Boat. In a Petition of the Mariners of Newcastle upon Tyne, recently

presented to the House of Commons, occurs this passage: ' That some hundreds

of your petitioners and their forefathers used formerly to earn a comfortable

pittance, when out of ships, in foy or assistant boats, transporting vessels,

which we are informed pay not a proportional tax on the labour they perform,

to our loss.' It appears from this that the occupation of the Foy Boats has

now failed, from vessels assisting themselves, or, in fact, performing their

own labour without assistance. As this service of assistance seems to have

been independent of the voy or farewell feast, and not always necessarily

accompanied therewith, we must allow the word to be here used in somewhat a

different sense. The Foy Boat was simply a way boat, or bateau de voye,

accompanying, piloting, and assisting vessels on the way or voyage" [See

note 44.]

Gallop.

[1791, Part II., p. 928.]

This word to gallop runs through all the provincial languages, French,

Italian, Spanish, as also German; and they have taken it, probably, one from

another: we may be thought to have had it from the French. As to the origin,

Mons. Menage brings it from calupare* citing Salmasius for this word, who esteems

it to be of Greek extraction;f but this is going very deep, and therefore I

should rather think it of Northern original, and in fact to be a compound

word, quasi ga loop, for which see Sewel's “Dutch Dictionary." A lope

way in Kent is now a short or quick way, or bridle-way. [The Anglo-Saxon is

Gehleapan, to leap.] L. E.

Gore.

[1792, Parti., p. gig.}

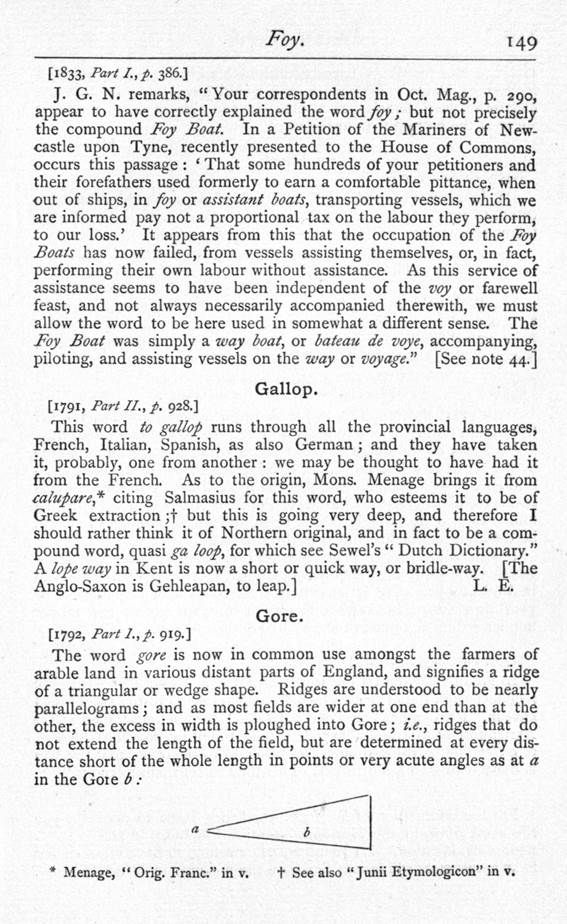

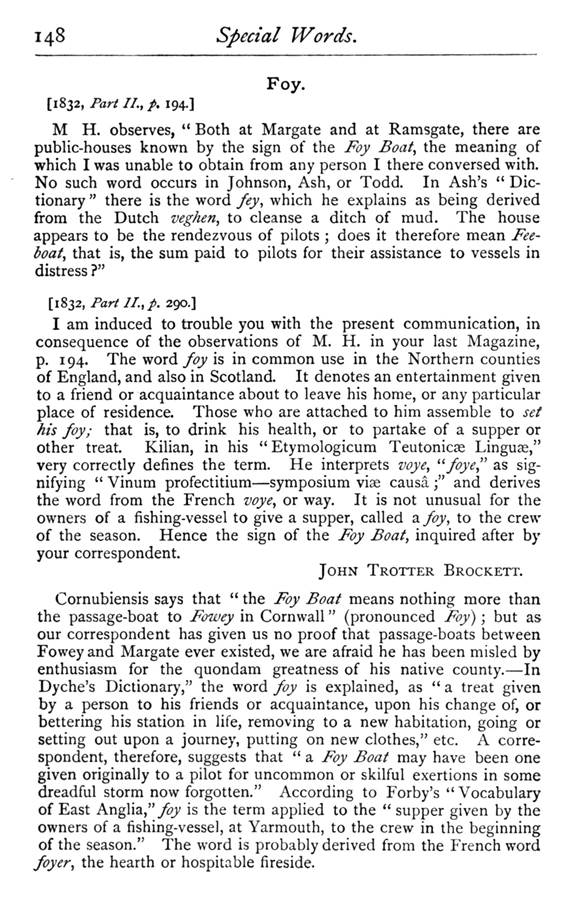

The word gore is now in common use amongst the farmers of arable land in

various distant parts of England, and signifies a ridge of a triangular or

wedge shape. Ridges are understood to be nearly parallelograms; and as most

fields are wider at one end than at the other, the excess in width is

ploughed into Gore; i.e., ridges that do not extend the length of the field,

but are determined at every distance short of the whole length in points or

very acute angles as at a in the Goie b:

Menage, “Orig. Franc." in v. t See

also “Junii Etymologicon" in v.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd D4478) (tudalen 150)

|

150 Special Words.

If Nugaculus (or \V. W.) had consulted his

wife or his sempstress, instead of Bailey's Dictionary, she would have told

him that the chemise of every female has a gore on one side of it, to render

it wider at the bottom than at the top.

M .

Hitch.

[1799, Parti,, p. 29.]

Dr. Johnson, in explaining the word hitch, says, “to hitch, v.n., to catch,

to move by jerks." I know not where it is used but in the following

passage; nor here know well what it means:

"Whoe'er offends, at some unlucky time Slides in a verse, or hitches

into rhyme."

Pope, “Im. of Hor.," b. ii., sat. I.

Mr. Wakefield, in a critique on this, says that “the word in question is used

in the Northern counties for getting into a place sideways, with difficulty

and contrivance. The proper term, I apprehend, is edge; so that the distich

would be correctly written:

“Whoe'er offends, at some unlucky time Slides into verse, and edges into

rhyme."

With great deference to two such respectable authorities, I differ from them

both. Without being able to refer to a printed authority, I can speak of the

usage of the word as being quite familiar to me in the sense of a hindrance,

an interruption; the business hitches it does not go on smoothly; there is

some hitch in the way. This seems to me to give the meaning of Pope; that one

who has offended him is sure to be brought into a verse, though the doing so

should be difficult, and make a hitch in the rhyme.

I wish some one of your Northern friends would let you know whether the word

used by them in the sense given by Mr. Wakefield is hitch or edge. The latter

certainly means getting into a. place by your own effort, but with difficulty

and contrivance; the former implies a difficulty put in the way by another person.

S. H.

[!799> Part I.) pp. 122-124.]

In my observation on the word hitch, p. 29, I said that I did not recollect

any printed book which I could quote to justify the sense I gave it. I have

since found one. In Mr. I. Middleton's "View of the Agriculture of

Middlesex" [1798] (a book full of information), he says, p. 93, “The

harrows so often hitch one on to the other, that the man is obliged to stop a