|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5001)

|

The Rhondda Leader, 20-10-1906

“Talcen y Byd.”

“The Alps of Glamorgan.”

(By Rev. JOHN GRIFFITH, Author of “Edward II. in Glamorgan.”)

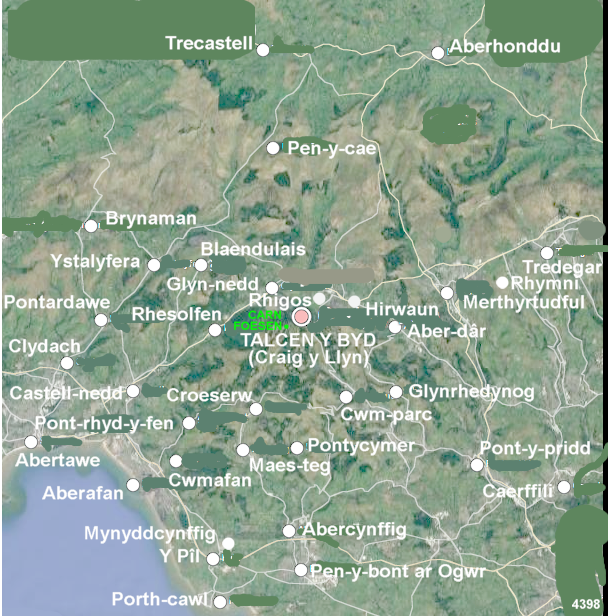

If the course of the river Cynon, which is fairly straight, extended to the

confluence of the rivers Nedd and Mellte, the courses of the Cynon and the

Nedd, almost equally long and straight, would form a right angle. At that

angle met the boundaries of three ancient principalities, Morgannwg,

Brycheiniog, and Dinefwr, and of two dioceses, Llandaff and St. David’s. At

that inter-state cockpit the interests of Morgannwg have always been well

guarded by an escarpment, which also forms a rough rectangle and extends a

good way down both the Nedd glen and the Cynon valley. It is known to

geologists as the “great Pennant scarp,” and to the natives, with exquisite

propriety, as “Talcen y Byd” (“The World’s Forehead”). It was to Morgannwg

the angle of greatest resistance and a flying wedge of great strategic value.

As “Talcen y Byd” is also the highest point in

Glamorgan, with all the ridges and glens between the Tâf and the Nedd more or

less joined to it, running out from it like so many radii within a

quarter circle, its strategic importance as the headquarters of the Blaenau

as against the Bro may be easily appreciated. Gwlad Forgan, or Glamorgan,

strictly speaking, as distinguished from the larger Morgannwg, was placed

between “Talcen y Byd” and the deep sea, and its peace and prosperity

depended

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5002)

|

more on the goodwill of the lord of “Talcen y Byd” than on the

guardian of its sea-board. It took the Norman lord of Cardiff two centuries

to annex “Talcen y Byd” to his estates; that is, the latter never knew a

Norman lord, and its final annexation by an Anglo-Norman was accomplished by

an astute statesmanship on the one part, and by the operation on the other

part of a natural law which eventually resulted in the re-conquest of the

Vale by “Talcen y Byd,” a conquest the nature and extent of which may be seen

in the fact that the most thoroughly Normanised county of Wales was, at the

beginning of the last century, in sentiment and speech, as thoroughly Welsh

as any part of Wales. It was from “Talcen y Byd” that the Normans derived

their inspiration to build their magnificent “blockhouses,” which afforded

great sport to the former to demolish.

The Normans are but a vague memory, and their castles have only some

archaeological value, but “Talcen y Byd” was never so dominant as at the

present moment, not over Glamorgan only, nor Wales, nor Britain; but as

Westminster is metaphorically, “Talcen y Byd” is literally the seat of the

might of the British Empire. The supremacy of Britannia as mistress of the

sea depends on her possession and wise utilisation of “Talcen y Byd.” In

scientific prose, “it is the headquarters of Welsh coal-mining, and

especially of the mining of the best quality of the Welsh steam coal.” The

name of the Pennant scarp, which was

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5003)

|

given to it by some unknown genius before the first quarter of

the last century, is severely scientific, historically true, truly poetical,

and profoundly prophetic.

Incalculably valuable as “Talcen y Byd” is to Britain, it will not help the

purpose of this light sketch to labour that point. All the world knows the

Rhondda Valley, but comparatively few know Glyn Rhondda. Again, the apparent

total absence from the district of Roman, Saxon, Norman, and English

monuments and remains may have given to many an impression of archaeological

poverty. There is an almost absolute destitution in the Rhondda of remains of

the cultures mentioned, but that fact, to my mind, clears and simplifies the

situation greatly, so that it is with some confidence that I invite attention

to a truly British museum in situ on still British soil. To visit this museum

you only need to know some Welsh. A smattering of Irish would be very handy,

while a dash of Pictish would be more valuable than all you know about the

Romans, Saxons, and Normans. It is also a distinct advantage to know where

you are at at the beginning of the inquiry, that you are plunging into the

pre-historic unknown. You can choose for starting point either the lowest

downward limit of time which is the upward limit of the historian, or if the

dawn of history will not do, you can start at once with the dawn of the

Bronze Age, and help us to decide how much earlier our characteristically

neolithic remains may be. The three great pre-historic Ages - Neolithic,

Bronze and Iron - have already been made, out there, but one is not satisfied

with such

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5004)

|

an ordinary record. The Pict, the Goidel, and the Brython are there right

enough, but so they are everywhere in the adjoining districts. But the

Rhondda Pict, who was probably slightly above what we consider medium size,

with a cephalic index of 84, could hardly sleep comfortably, except

dog-fashion, in the tiny night-shelter which may be seen almost everywhere in

the far-away hollows around “Talcen y Byd.” The more one learns of the type

of man who introduced the beaker, or “drinking-cup,” into the Rhondda, the

historic reality of Rhondda fairies seems to become more and more

problematical. It is the great number of the remains, in situations most

favourable for their preservation, of pre- historic outward appearance,

proved to be so wherever excavated, together with the fact that the whole

district is a “terra ignota,” speaking generally, to archaeologists, that

encourages the hope that “Talcen y Byd” may yet figure in archaeology as in

geology and state-craft - even as a Hallstadt or La Tene. The visible remains

of two classes of pre-historic sites in one parish alone I have roughly

estimated to be over two hundred, and they seem quite as thick in the

adjoining parishes; but our best early Bronze Age finds were found in a cairn

levelled to the ground, and finds of possibly an earlier period were made at

a spot purposely levelled as if to be the floor of a barn. At three other

spots where finds were made there was nothing to indicate the character of

the site. I mention this here because only one out of many visible remains

that we have excavated had been left undisturbed, but that that is no

criterion to go by in calculating the chances of digging. So with the

obliterated and conspicuous remains, the archaeological richness of the

district is above question.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5005)

|

“Talcen y Byd” is the largest, highest, and most imposing

remnant of a plateau of Pennant Grit. The tableland character of the district

is evidenced by the flat tops of the adjoining hills, which are of fairly

uniform height, allowance being made for the tendency of the whole country to

gain in elevation northwards. Though the range of the Brecknock Beacons is

still higher, it is to be noted that “Talcen y Byd” is about equidistant

between the sea and the Beacons, and tnat there is a marked depression

between the highest Glamorgan range and the Beacons.

From a height of 600 or 700 feet at Hirwaun, the ground rises abruptly to the

great Pennant Scarp, which is unbroken from the Cynon to the Neath, and which

presents a bold front to the north with a maximum height of 1,969 feet (“The

Geology of the South Wales Coalfield,” Part 4, p. 113). From all directions

it is a position of characteristic independence. For the homage “Talcen y

Byd” exacted from the lowlands, it was well able to guarantee the latter’s

integrity against invaders from the north. In the early annals of Margam

Abbey, we find the lord of “Talcen y Byd,” otherwise Glyn Rhondda,

undertaking the protection of the monks against the men of Brycheiniog.

During the Ice Age, a great mass of ice moved down from the Beacons with the

intention of overwhelming Glamorgan, but “Talcen y Byd” remained firm, and

actually diverted the ice to the south-east along Aberdar, and to the

north-west along the Nedd itself, true to its name, uplifting a cool and

clear forehead in the midst of a sea of ice. But not to be outdone in the ice

business, it developed glaciers of its own for the Rhondda, Ogwr, and Avan

glens.

(To be continued).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5006)

|

The Rhondda Leader, 27-10-1906

“Talcen y Byd.”

Important Dialect Boundary.

[By Rev. JOHN GRIFFITH, Author of Edward II. in Glamorgan.”]

(Continued).

Dialect evidence seems to show that it was for a long time a barrier or

long-respected boundary between the Goidels and the Brythons, for “Talcen y

Byd” is the western limit of the narrow “a” area in Glamorgan. Throughout the

history of Wales, as far as known, it formed the western limit of Morgannwg

proper, a limit respected until the formation of the present county in the

time of Henry VIII. To the present time the Goidelic complexion of the

topography west of the “Talcen” is very pronounced, and the richness of the

district in fairy lore points to the same conclusion. As an inter-state and

inter-racial boundary, it must be remembered that the ridge which it crowns

extends right to the sea, the only point where the Glamorgan hill system

touches the sea. The foothills from Abergavenny to Margam describe half the

circumference of a circle, but leaving everywhere a wide margin of lowlands

until the mouth of the Avan is reached. There, two parallel ridges reaching

from the sea to the Beacons, with the courses of the Avan, Nedd, and Tawe,

form an effective barrier resembling the fortifications of many a hill earthwork.

A quarter of that circle is dominated by “Talcen y Byd.”

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5007)

|

Professor Anwyl says: - “In Glamorganshire and Monmouthshire,

‘ä’ (for ‘a’) is used in the dialect of the district east of the Vale of

Neath, thus comprising Monmouthshire and the greater portion of

Glamorganshire. The boundary between this dialect and that of Breconshire is

practically the boundary between the counties. It appears, however, that ‘ä’

is not used in the Vale of Neath itself, nor yet in Hirwain by natives. In

Cefncoedcymmer ‘ä’ is found, but not in Aberavon; is also found east of

Bridgend in the Vale of Glamorgan.” (“Transactions of the Guild of

Graduates,” University of Wales, 1901, p. 40).

I can add from personal observation that the narrow “a” is used at Mynydd

Cynffig, a few miles to the east of Aberavon, in the upper part of the Ogwr

glen, in the Rhondda and Aberdar. On the other hand, Mr. D. Williams, of

Ogmore Vale, a teacher of sounds, that is, music, who has given special

attention to this dialect boundary, informs me that the narrow “a” is not

found at Cwmavon, a few miles above Aberavon. At Cymmer there is a trace of

it and he confirms Prof. Anwyl’s statement about Hirwaun. Cymmer is

practically the head of the Llynfi valley, though actually on the course of

the Avan. Besides, a great road from the south-east crosses the Avan glen

there. We find, therefore, the narrow “a” close to Aberavon in the lowland,

and at the head of all the valleys abutting on the east the ridge of “Talcen

y Byd,” namely, the Llynfi (and the Garw most likely), the Ogwr, the Rhondda,

the Cynon, and the Tâf as high up as the confluence of the branches of the

Tâf, that is, the head of the Merthyr valley. On the other hand, not the Vale

of Neath, but the ridge of “Talcen y Byd” seems to be the true dividing line.

The whole of that ridge, including its broad base

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5008)

|

from the Nedd to the Avan, belongs to the broad “a” district.

The existence of such a marked dialect boundary “seems to indicate,”

Professor Rhys says, “that at one time that part of the southern border of

the Principality came under the influence of some Brythonic people pressing

westwards, such, for anything known to the contrary, as the Dobunni near the

mouth of the Severn may have been.” (“The Welsh People,” p. 22). The map of

The British Isles in the First Century A.D. published in the same work, does

not show any Brythonic people west of the Wye and south of the Somerset Avon.

But as the mouths of both rivers, with the country between, the estuary of

the Severn in fact, were in the possession of Brythons, and as the Gwent and

Morgannwg narrow “a” area has always been easily accessible to masters of the

Severn estuary, that area may have come very early under Brythonic influence.

But the mountain barrier north and west of a line from Abergavenny to

Aberavon seems to have remained for a long time stubbornly Goidelic. The

mouths of the Avon, Nedd, and Tawe, with the two ridges between, reaching

from the sea to the Beacons, may not only be looked upon as defences

consisting of three ditches and two ramparts - and of the three river courses

the Avan mostly resembles a V-shaped fosse - but also as forming the key

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5009)

|

to the whole Beacons position. That position did not invite frontal attacks,

but a power, or a race in possession of the sea-reaching ridges west of the

Avan, and of the Usk valley would have either taken the position on the

flanks or utilise it to the best possible advantage. The Goidels, who seem to

have held doggedly to the ridges and valley mentioned, had the best of the

natural position. The Romans eventually penetrated it, but that was before it

ceased to be Goidelic ground. As part of the large question of the Goidelic

fringes of Wales down to post-Roman times, the twin ridges between the Avan

and the Nedd deserve careful attention.

The Brythons as Cymry eventually imposed their rule and speech over all

Wales, but it may be that the forces commanded by Vortimer in his battles

were largely Goidels. At any rate, one of his battles seems to have been

fought on one of the spurs of “Talcen y Byd,” an ideal situation for a united

stand by the neighbouring Goidels and Brythons against the new invaders. In the

text of Nennius favoured by Mommsen, one battle is described: -

“Tertium bellum in campo iuxta lapidem tituli, qui est super ripam Gallici

maris, commisit et barbari victi sunt et ille victor fuit et ipsi in

fugam uersi usque ad ciulas suas mersi sunt in eas muliebriter intrantes.”

In the “Nennius Interpretatus” the words are “et bellum super ripam maris

Icht et Saxones in fugam versi sunt usque ad suas ciulas muliebriter.”

(Mommsen’s “Chronica Minora,” III., pp. 187, 188).

Muir n-Icht is the Irish name for the English Channel, meaning the Sea of

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5010)

|

Icht, or Ictian Sea.” Guorthemir - Gwrthefyr - Vortimer was

the son of Guorthigirn - Gwrtheyrn - Vortigern, “whose name outside the

Hengist story is found to have been more at home in Ireland and Brittany than

in Wales” (“The Welsh People,” p. 82). The movement represented by the names

may be regarded as an amalgamation of the native population, reinforced from

Ireland, for the purpose of opposing the Brythonic tribes and the Saxons. In

place-names and legend Gwrtheyrn is associated with the coast of Carnarvonshire,

the Teifi valley, and the upper part of the Wye. Assuming that he settled in

the district called Gwrtheyrnion, it is not unreasonable to connect one of

his son’s battles with the region of “Talcen y Byd.” For the site of the

battle described we must look for a spot offering some special natural

advantage close to the sea. Assuming that the enemy landed at Aberavon, we

have Mynydd Margam to consider. That mountain is chiefly known for its fine

inscribed stone, called “par excellence” Y Maen Llythyrog (The Lettered

Stone). Its vague popular name corresponds with the equally vague description

of Nennius as “lapis tituli” (The Stone of the Epitaph). A superstition

connected with the stone has helped to give it a special distinction. It is

still believed that whosoever readeth the inscription will die very soon. The

site is also a splendid “campus,” a mountain flat where a vast army could

manoeuvre. There is a Roman camp close by the stone and a Roman road leading

from it right to “Talcen y Byd,” from which direction we may assume Vortimer

to have marched against the invaders. On that road, a mile or two above the

Maen Llythyrog, there is one of those place-names which form a sort of cordon

along the circular border of the foothills all the way from the Ebbwy to the

Nedd.

(To be continued).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5011)

|

The Rhondda Leader, 3-11-1906

“Talcen y Byd.”

Home of Romance.

I refer to place-names with the element “Saeson.” Some may have been

recognised boundaries between the Welsh and the English settlers, but they

may all be safely treated as marking the “ne plus ultra” of the English

invasion of the hills. Well, there is a Rhiw Saeson on the Roman road that

leads from “Talcen y Byd” to the Maen Llythyrog, and, curiously, the hill

above the spot is called Tor y Cymry, which, I think, is a corruption of Tor

y Cymmerau. The enemy defeated there would be driven helter-skelter along

Mynydd Margam or down the Avan glen and into his ships. It is also a curious

coincidence that the Maen Llythyrog, otherwise the Bodvoc Stone, commemorates

a Catutegernios, and Catigern, according to Nennius, was another son of

Gwrtheyrn. I may mention also that a place near Rhiw Saeson is called Castell

Cadarn, which, with Cwm Cadarn and Cerrig Cadarn in Brecknockshire, near the

supposed stronghold of Gwrtheyrn, require explanation. Altogether it seems

fitting that “Talcen y Byd” should have figured in such a struggle as that

connected with the name of Vortimer.

Leaving the mere commercial and strategic value of “Talcen y Byd,” let us now

ascend to the higher plane of romance. The district is rich in unwritten

Mabinogion, just as it is rich in unworked archaeological remains. In

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5012)

|

using the term Mabinogion I have in my mind the “Kulhwch and Olwen” type. The

compiler of that tale took a very old tale for leading incident, the

boar-hunt. “Around this theme of immemorial antiquity,” says Mr. Alfred Nutt,

the story-teller grouped numerous fairy tale traits and incidents drawn

undoubtedly from the rich store of popular tradition, and he handled the

whole in a tone and spirit so akin to the nature of his subject-matter as to

produce what is, saving the finest tales of the ‘Arabian Nights,’ the

greatest romantic fairy tale, even in its present fragmentary condition, the

world has ever seen.”

Sitting down on a fine midsummer day on the highest point of “Talcen y Byd”

one could easily compile at least a parody of that tale, utilising only the

genuine traditions of the spot. But how much more valuable the tale of

“Kulhwch and Olwen” would have been if the compiler had contented himself

with noting down his materials simply in the spirit and method of a

present-day folklorist? But though there is great danger to one who has

fallen victim to the enchantment of “Talcen y Byd” to be carried off his

critical and scientific feet into weaving romances and evolving Druidical

systems, I am resolved to make a great effort to keep to some facts of folklore

and archaeology which others, if they like, can convert into sagas. That it

means a great effort to do so I am reminded by the sad fate of others who

have attempted the same task.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5013)

|

It was from “Talcen y Byd” that Iolo Morgannwg caught the inspiration of his

life-work. When a lad it was his great delight to visit his relatives at Pont

Nedd Fechan, and would often run away from his home the Vale to that

fairy-bewitched spot, and each time he had to cross “Talcen y Byd.” But, oh!

the pity of it! that he preferred compiling, if not evolving, a system of

Barddas to recording the dying depositions of Dame Tradition. But knowing

“Talcen y Byd” as I do, I cannot blame him for losing his intellectual

balance on that dizzy height.

His son and successor to the Arch-druidism caught likewise his inspiration

from “Talcen y Byd.” He gave us some most useful information about the Vale

of Neath. As to the rest, he was content to be his father’s son.

Had Southey, Iolo’s friend, settled at “Talcen y Byd,” as he once seriously

intended, we might have had written the great epic of “Talcen y Byd,” based

on genuine traditions gathered on the spot, instead of his insubstantial

“Madoc,” based on nothing.

Taliesin ab Iolo’s successor to the Arch-druidism, Myfyr Morgannwg, was a

genuine son of “Talcen y Byd.” Born and brought up on its south-western

slope, he spent his long and busy life fairly within sight of its summit. He

found in Barddas a solution for all the great problems of the universe. When

dying, he commanded his daughter to place copies of all his published works

under his head in the coffin. But I have waded through his laborious book,

“Hynafiaeth Aruthrol y Trwn, neu Orsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain, a’i Barddas

Gyrin,” [sic; = Gyfrin] in the hope of finding some records of at least

tit-bits of local folklore, but I have been

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5014)

|

greatly disappointed. Had “Myfyr” lived in Anglesey, he could

hardly have produced a book with so little local colour. The solitary

exception seems to be the following flourish: - “Y man pennodol yn Ynys

Brydain ag ydys ddyledus iddo am gadwraeth yr Orsedd Arddunawl hon drwy y

ddwy fil ddiweddaf o flynyddoedd yw Gwent a Morgannwg, a’r unig fan ei

cynnelir y dydd hwn yw ar y Maen Chwyf, o fewn swyn-gylch Llŷs Ceridwen

a dadblygion y Sarph Dorchog, ar lan y Tâf.”

“Morien,” “Myfyr’s” successor of the Iolo Druidical succession - for there

seems to be two, if not three, such successions now in Wales - was brought up

on the Rhondda side of “Talcen y Byd,” and he has written a pile of books and

numberless articles on various matters connected with the region. As to his

Druidism, “Morien” seems to be a faithful follower of “Myfyr,” so far as an

ordinary mortal can understand the cult. “Christianity,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5015)

|

in Wales, from the first coming there had been, most

mysteriously, closely associated with the earlier religion of the Isles of

Britain. That creed has been known under the names Druidism, Bardism, and its

adherents were known as Mabinogion, or adherents of the Infant Son. They

personified the Sun and called him Taliesun, etc., and believed a new infant

Sun was born every year; on December 27th, but that the first Infant Sun

called also “Y Coronog Vaban,” or the Royal Babe, was born at the dawn of

creation, from the Royal Barge of Cariadwen, Queen Spirit of Heaven, on

December 25th.... “Myfyr Morgannwg” adopted the extraordinary view that

Christianity was Druidism in an Oriental disguise, and his wrath was great

when descanting on his theory that the Christian religion is Druidism in

Jewish clothes.” (“Morien’s” Hist. of Pontypridd, pp. 83, 84).

Of the four Archdruids of the Iolo succession, “Morien” has made most use of

local colour in his elucidations of the cult. Whatever about his Druidism

“Talcen y Byd” is never out of his mind. He has in his way actually written

some Mabinogion of the type of “Kulhwch and Olwen.” In his “History of

Pontypridd and the Rhondda Valleys,” for instance, he weaves local

place-names and traditions into a philosophy that is to unravel the enigmas

of the universe.

(To be continued).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5016)

|

The Rhondda Leader, 10-11-1906

“Talcen y Byd.”

[By Rev. JOHN GRIFFITH, Author of Edward II. in Glamorgan.”]

(Continued).

Its Free-Thinkers.

Few now living know “Talcen y Byd” as well as “Morien” does,

and I speak with sincere gratitude to him for the valuable clues his writings

afford. The late Dr. Price, of Llantrisant, was the associate of “Myfyr

Morgannwg.” More than any other modern Druid, he laboured to give a practical

expression to the occult teaching of his associates. His dress, I would

suppose, was that of the early Bronze Age, and he commanded that his body was

to be cremated on the southernmost spur of “Talcen y Byd,” which command was

obeyed. He took a leading part in the Chartist movement. He frequently

appeared in the courts, conducting his own cases and basing his arguments on

the old Welsh laws. Treating Christianity “Myfyr”-fashion he named his son

“Iesu Grist.” I well remember the golden-headed lad, and the strange feeling

that possessed me when I saw him in a Sunday School at Llantrisant learning

about the Founder of Christianity. Dr. Price appeared to all who knew him as

the soundest and sanest of men, a religious man in his strange way, and full

of noble deeds; yet through his life-long protest against the

conventionalities he is always referred to as “the eccentric Dr. Price.”

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5017)

|

Nothing like an adequate sketch of “Talcen y Byd” can be

written without some account of its typical human products. The five I have

named represent the “Talcen” type, and their cult is strictly local. “Myfyr”

and Dr. Price I remember as slightly-built men of medium size, but as I never

saw the former without his slouch hat, nor the latter without the fox-skin

which dangled about his ears, I can venture no opinion as to their cephalic

indications beyond an impression from good portraits of both now before me,

that they were long-headed. In a word, the “Talcen” breed are daring

free-thinkers in the unabused sense of that term. Lollardism and

Protestantism found there a safe nursery. At the foot of the “Talcen” proper,

at Glyn Eithinog, dwelt Thomas Llewelyn, a bard who is said to have

translated portions of the Bible before Dr. Morgan, who is mentioned as one

of the free lance preachers which Grindal licensed, though I failed to find a

copy of his license at Lambeth, and who is regarded as the father of Nonconformity

in the district.

A native of “Talcen y Byd,” Thomas Stephens, was the father of historical

criticism applied to Welsh literature. Under its shelter, at Hirwaun, the

late Dafydd Morgannwg wrote the best general history of Glamorgan. Under its

beetling Aberdâr brows the elective Archdruid, Dyfed, nursed his muse. The

late Judge Gwilym Williams was, and Sir Marchant Williams is, above all else,

genuine “Talcen” gentlemen. Mr. Tom John, the ex-President of the National

Union of Teachers, is another.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5018)

|

Mabon was brought up on a narrow “a” boundary at Cwmavon, and he continues to

rule the realm of Labour from “Talcen y Byd.” Sir William Thomas Lewis was

born in sight of the “Talcen,” and he has been its real master for many a

year. On its south-western slope, in Llangeinor, was born Dr. Richard Price,

who was considered in his day one of the three greatest men in Europe and

America. John Thomas, King’s harpist, is a “Talcen” native. The list may be

made much longer, but it may suffice to show the persistence of the type of

homo which only “Talcen y Byd” could produce. Of the “Talcen” druids and

bards I have mentioned only those of the last century, but the Bards of Tir

Iarll, the western slope of the “Talcen,” formed an independent bardic

fraternity dominated as usual by “Talcen y Byd.” Dafydd Benwyn, for instance,

was a native of the “Talcen,” and at Aberpergwm the last “bardd teulu,”

Dafydd Nicolas, was kept. That reminds me of the fact that a “Talcen” native,

Miss Jane Williams (Ysgafell), preserved for us a fine collection of Welsh

airs, and thinking of the Aberpergwm family brings to mind the fact that

Oliver Cromwell belonged to that family, and “Talcen y Byd” explains that

strange individuality.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5019)

|

Besides “Morien” I must acknowledge with gratitude the

indebtedness of all lovers of “Talcen y Byd” to “Cadrawd” for his “History of

Llangynwyd,” to Mr. Taliesin Morgan for his “History of Llantrisant,” to the

late Glanffrwd for his “Plwyf Llanwyno,” and to the late Mr. Jenkin Howell

for his articles in “Cymru” on the parish of Aberdâr. “Glanffrwd” especially

was an embodiment of the spirit of “Talcen y Byd,” and his book, which is

more of a parochial epic than a parish history, was written from his North Wales

home, which shows how “Talcen y Byd” never lets off its victims.

“Brynfab,” who worthily maintains - almost alone, alas! - the strictly local

bardic traditions of the “Talcen,” has enriched the files of “Tarian y

Gweithiwr” with most valuable information of by-gone Glyn Rhondda.

As we have no definite account of any conquest of “Talcen y

Byd,” it will not appear strange that, it remained an untrodden track to the

tourist until the beginning of the last century. Nearly fifty years later we

find the Rhondda vaguely described in a footnote to the “Iolo MSS.” as a

place west of Aberdar. Malkin was the discoverer of the Rhondda, and he was

fully conscious of the fact – “I question,” he says, “whether any part of my

tour is better furnished with its apology, if an untrodden track may excuse

an author for supposing that, his observations are of sufficient value to

come before the public.”

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5020)

|

The Rhondda Leader, 17-11-1906

“Talcen y Byd.’

As Malkin saw it 100 Years Ago.

[By Rev. JOHN GRIFFITH, Author of Edward II. in Glamorgan.”]

(Continued).

“The vale is very much confined, admitting only a road and a few fields on

one side, and on the other, the cliffs rise perpendicularly from the water in

all their naked grandeur, but all clothed on the top with some of the

choicest and most majestic timber that Glamorganshire produces. The union of

wildness with luxuriance, and of solemnity with contracted space, is here

most curiously exemplified.” That refers to the portion of the valley between

Pontypridd and Cymmer. “Travellers in any sort of carriage are precluded from

adopting this interesting route.” “A country of uncommon wildness.” He saw a

grove of oaks, remarkable for their height.” “It may be observed generally

that among those mountains, the oak, if it grows at all luxuriantly, is drawn

up to an uncommon tallness.” Dinas mountain, at Trewilliam, a rocky ridge,

grand in its elevation, and most whimsical in the eccentricity of its

shapes.” “Towers of limestone (sic, sandstone rather) occasionally start up,

which overhang the road, and seem to endanger the traveller.” Higher up he

finds “a degree of luxuriance in the valley infinitely beyond what my

entrance on this district led me

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5021)

|

to expect. The contrast of the meadows rich and verdant, with

mountains the most wild and romantic, surrounding them on every side, is in

the highest degree picturesque.” Poor Malkin is now in the toils of “Talcen y

Byd,” and he was not a native, mind you! He regrets that he has “no common

language in which to converse” with the natives. “Indeed, how can a man be

said to know the world, without knowing Ystradyfodwg?” The “Talcen” speaks

these. After passing the parish church, where “the drowsy hum of mountain

scholars, twanging their guttural accents to their Cambrian pedagogue in the

church porch,” greeted his ears, “the rocks and hills gradually close in

becoming bolder and more fantastical in their appearance.” These he calls the

Alps of Glamorganshire.” The Rhondda side of “Talcen y Byd” he describes as

follows: “The front of this narrow dell is filled up by a single cliff, high,

broad to the top, and as it were regularly and architecturally placed,

appearing as much the result of design, as those on the sides seem to

indicate the fortuitous vagaries of sportive Nature. The height of this

mountain (Pen Pych) seems much greater than it is, from its rising abruptly

from the level ground, unencumbered by hillocks at its foot, the

perpendicular nearly unbroken from the summit to the river that passes its

base.”

“The path up the mountain (on the east of the village of Blaenrhondda), which

is the highest in Glamorganshire, is winding and difficult.” The fall of the

Rhondda Fawr “well repays the labour of the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5022)

|

journey.” On gaining the summit (the “Talcen”), what he sees

“all bring to the mind the best descriptions of Alpine scenery, though on an

inferior scale.” “The upper part of the Ystradyfodwg parish is untameably

wild, as anything that can be conceived; and the few who have taken the pains

to explore the scattered magnificence of South Wales, agree in recommending

this untried route to the English traveller as one of the most curious and

striking in the principality, not excepting the more known and frequented

tour of the northern counties. Hanging over the steep descent (that is, over

the ‘Talcen’ itself), you have immediately below you Llyn Vawr, a

considerable lake, the largest in Glamorganshire. It is of great depth, and

seems to be formed by the floods, which in heavy rains must pour down the

perpendicular sides of the mountain in one broad continued sheet. The deeply

furrowed troughs, as far as the pool extends, worn by the streams, which had

long ceased to flow, assign a sufficient cause for so large and permanent a

body of water. This lake affords ample scope to the fisherman, and attracts

the lovers of that amusement from the whole country round.” “A stranger has

considerable difficulty in descending a narrow path, worn upon the side of an

almost perpendicular declivity.” “The way after descending the mountain is

rough and dreary, over barren and unprofitable ground.” After finding a

“complete course of bacon and eggs” at Pont Nedd Fechan, “I consider it as a

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5023)

|

necessary caution to my reader to inform him that he must

travel thirty miles from the Duke’s Arms in the Vale of Tâff (at Pontypridd)

to Pontneath Vechan, without expecting the most humble accommodation.” He

seems to have judged the distance by his rate of travelling, making it about

ten miles longer than it really is.

The reader will have noticed that I use the name “Talcen y Byd” occasionally for the hill

district between the Cynon and the Nedd. As the scarp gives unity to the

whole district, and as no other name in present use suits my purpose so well,

I would recommend its adoption as the archaeological name of the Glamorgan

Alps. Perhaps the following striking archaeological coincidence will further

justify the resuscitation of the name, with an extended application.

In Lady Guest’s translation of the Mabinogi of Branwen, we read the following

part of the account of the disastrous

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5024)

|

expedition of Bendigeid Yran to Ireland: Now the swineheards

[sic; = swineherds] of Matholwch were upon the sea-shore, and they came to

Matholwch. ‘Lord,’ said they, ‘greeting be unto thee.’ ‘Heaven protect you,’

said he; ‘have you any news?’ ‘Lord,’ said they, ‘we have marvellous news, a

wood have we seen upon the sea, in a place where we never yet saw a single

tree.’ ‘This is indeed a marvel,’ said he; ‘saw you aught else?’ ‘We saw,

lord,’ said they, ‘a vast mountain beside the wood, which moved, and there

was a lofty ridge on the top of the mountain, and a lake on each side of the

ridge. And the wood, and the mountain, and all these things moved.’ ‘Verily,’

said he, ‘there is no one who can know aught concerning this, unless it be

Branwen.’

“Messengers then went unto Branwen. ‘Lady,’ said they, ‘what thinkest thou

that this is?’ ‘The men of the Island of the Mighty, who have come hither on

hearing of my ill-treatment and my woes.’ ‘What is the forest that is seen

upon the sea?’ asked they. ‘The yards and masts of ships,’ she answered.

‘Alas,’ said they, ‘what is the mountain that is seen by the side of the

ships?’ ‘Bendigeid Vran, my brother,’ she replied, ‘coming to shoal water;

there is no ship that can contain him in it.’ ‘What is the lofty ridge with

the lake on each side thereof?’

‘On looking towards this island he is wroth, and his two eyes, one on each

side of his nose, are the two lakes beside the ridge.’

(To be continued).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5025)

|

The Rhondda Leader, 24-11-1906

“Talcen y Byd.”

[By Rev. JOHN GRIFFITH, Author of Edward II. in Glamorgan.

(Continued).

Bran was evidently a deity, whether a creation of the Goidels or non-Aryan

natives, we cannot say for certain. Professor Rhys says: “He sat, as the

Mabinogi of Branwen describes him, on the rock of Harlech, a figure too

colossal for any house to contain or any ship to carry. This would seem to

challenge comparison with Cernunnos, the squatting god of ancient Gaul,

around whom the other gods appear as mere striplings, as proved by the

monumental representations in point” (“Celtic Folklore”, p. 552).

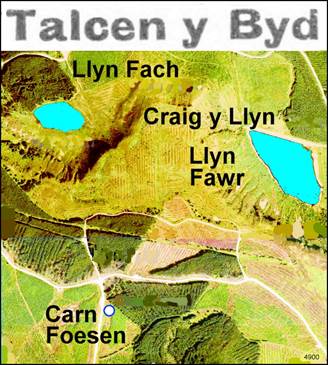

What strikes me is the probability that some well-known landscape feature

furnished the story-teller with the description he gives of Bran, even if

such a landscape feature was not actually an object of worship. It happens

that “Talcen y Byd” presents to the west precisely the same aspect as Bran’s

face did to the Irish. There is the broad forehead. There is the sharp

promontory for a nose, and there are the two lakes, Llyn Fawr and Llyn Fach,

for eyes. What specially deepens the impression of a colossal image is, with

the nose and the eyes, the extension of the line of the forehead itself

across and above the bridge of the nose, and above the forehead the gentle

dome-shape crown of the mountain, the highest point in the county. I cannot

say how such a combination of features strikes one from the opposite ridge of

Cefn Hirfynydd on the north-west, but a glance at any map will bear out my

description of it. Is it likely that any other spot in Wales fits so well the

image of Brân? Situate on the eastern

side of a famous boundary line,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5026)

|

who knows with what feelings it may have been regarded by the

Goidels, say, on the west of the Nedd? Though I am not aware that this

colossal image has been noticed before, the name “Talcen y Byd” shows that it

may have been noticed in its entirety. It is really impossible to notice the

“Talcen” without noticing the nose. The Welsh would have no better or handier

name for such a promontory than “Trwyn.” Then, apart from the situation of

the two lakes on each side of the nose at “Talcen y Byd,” such pools seem to

have been once universally described as “Llygaid,” as springs generally were.

Llyn Fawr is in size and situation almost exactly like Llyn Llygad y Rheidiol

under Plinlimmon. In Cwmaman, Aberdâr, there is a place called Llygad Eglur,

meaning a spring that can be seen from a distance. There is Llygad Clydach in

Llanwynno, and in Llangeinor a group of springs which unite into a stream a

little below is called Llygaid y Ffynonau. So Llygad for a spring is common

in the district. The real names of the “Talcen” lakes have disappeared, but I

fancy Llyn Fawr must have been called once Llygad Gwrelych, or some such

name. Its oldest form in the local charters is Magna Pola, a translation of

Pwll Mawr, or, say, Llyn Fawr. But have we not an earlier name in Nennius?

Where else, I wonder, are we to look for one of the wonders of Britain which,

he says, is “in regione Cinlipiuc”, or “Cinloipiauc,” which he calls “Finnaun

Guur Helic,” or “Guor,” or “Gor,” Helic, or “Heilic.” I find more than one

Pwll Helig in Glamorgan (Chronica Minora, III., 214, 215). In the chapter

heading (p. 130) it is called Guorelic. It was evidently a pool or lake, and

not a mere well. Men fished it on four sides, each side containing a

different species of fish, which is bunkum, of course. The author probably

never saw it, and his statement that it was only twenty feet square and only

knee deep is manifestly inconsistent with its renown as a fishing resort. The

similarity of the name to Gwrelych, or Gwrelech, or Gwerelech, the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5027)

|

name of the brook that flows out of Llyn Fawr, is striking, enough to justify

this digression. Perhaps in Cinlipiuc we have a similarly vague reference to

the district as Gwynllywc or Gwenllwg-Wentioog, a district near enough to

suit the purpose of a wonder-hunter, who usually dislikes exactitude as

spoiling his business, so much about what I can only call a striking

coincidence, the resemblance between Bendigeid Fran on the war-path and

“Talcen y Byd” in repose.

That it is not unreasonable to think that “Talcen y Byd” may have been once

regarded as the embodiment of a divinity is not only shown in the general

prevalence of mountain worship, so to speak, everywhere, but especially in

the presence in the same district of many freaks of Nature which the natives

have labelled with suggestive names. At the back of the same mountain, on the

precipice under which the tunnel from Blaencwm to Blaengwynfi runs, there is

a striking resemblance to a human face. A cairn

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5028)

|

on the top of the mountain is called Bachgen Careg, and the

adjoining slope is called Mynydd y Ddelw. Guided by such names and feeling

sure that there was on the spot something to justify the use of such names, I

made a careful search for it among the “whimsical” and “fortuitous vagaries

of sportive Nature” as Malkin would say. The first day I spotted the rock

which presents the image I was searching for, but as I was looking at it from

one side I did not make out the image. The next day, with the aid of the

early sunlight in midsummer, I saw the image to the best advantage from the

road in front of Pen Pych. The face is slightly turned to the north-east.

Repeated visits to the spot have shown that the image must be viewed in the

early morning sunlight, when the scars on the face are toned down and the

shading shows the facial outline. The image must be some thirty-five feet

long, a squarish rock on the top resembling the diminutive cap which Tommy

Atkins sometimes wears. True to the name, Bachgen Careg, the face seems to be

that of a very big boy. I found the image quite unknown to the villagers and

natives, though they had preserved two suggestive names which they could not

explain. So far I have not found any legend or tradition about it.

(To be concluded).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5029)

|

The Rhondda Leader, 01-12-1906

“Talcen y Byd.”

(Continued).

[By Rev. JOHN GRIFFITH, Author of Edward II. in Glamorgan.”]

Arthur’s Sleeping-Place.

Passing the cairn of the Bachgen Carreg into Glyncorrwg, on the east side of

that glen is the well-known Maen yr Allor, an arrested landslip, the rock

dislodged forming a huge oblong exactly like an altar. The two lusus naturae

I have noted happen to be situate on the neck, so to speak, of the mountain,

of Brân’s face, or “Talcen y Byd.”

Arthur’s connection with “Talcen y Byd” “Talcen y Byd.” [sic] Other peaks in

the district will be noted in their turn. Arthur’s connection with “Talcen y

Byd” is most patent. A charter of 1203 mentions “Fennaun Arthur” (Arthur’s

Well) as a boundary point, between the head of the “Rotheni Maur” (Rhondda

Fawr) and Magna Pola (Llyn Fawr). A native of the adjoining parish of

Blaengwrach tells me that he knows the well by that name. It is one of the

springs of the Rhondda by Carn Mosyn, which he calls Carn “Moisa.” Both the charter

and the native place it at the top of the dome-shaped summit of “Talcen y

Byd.” Arthur there is clearly a divinity, a well divinity too, as he seems to

be also in Llanfihangel yng Ngwynfa, Mont., where there is a Ffynnon Arthur.

The fashion of resorting to mountain tops on Gwyl Awst is .

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5030)

|

known on the Beacons. Professor Rhys tells us of the Fan Fach custom, and the

late Rector of Vaynor relates the same of his parishioners on the east of the

Beacons. The custom doubtless arose from the worship of a mountain deity at

some well near or on the summit.

That is not all. My Blaengwrach informant says that a place by Blaengwrach

Farm is called Plas Arthur, and sometimes Stafell Arthur, where there is a

stone on which “Arthur Sant” used to preach. Arthur as a divinity would

naturally assume the role of a Christian saint, though the real Arthur was

not so regarded by some of the saints of his day. Blaengwrach Farm abuts the

western end of the “Talcen y Byd” scarp. I have not visited the spot, nor

have I seen the interesting traces of Arthur in Llanwonno, the eastern

extension of the scarp. “Glanffrwd,” in his “Plwyn [aic; = plwyf] Llanwynno,”

mentions Pont-Bren-Arthur (Arthur’s Wooden Bridge), and Llun-troed Arthur

(the Image of Arthur’s Foot) on the river Ffrwd there (p. 36). These

Arthurian place-names in the district will help to account for the fact that

of all

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5031)

|

the Arthurian legends in Wales, outside the Mabinogion, and

other old writings, “Talcen y Byd” has yielded the best. To Iolo Morgannwg we

are indebted for it. Professor Rhŷs gives it as the first of a group of

cave legends involving treasure entrusted to the keeping of armed warriors

(Celt. Folk, pp. 458-461).

At both ends of the parish of Ystradyfodwg there is a Craig y Dinas. The

southern one is actually in the parish of Llantrisant, but the mountain forms

the natural boundary of Ystradyfodwg on the south. “Morien” says that the

tale of Arthur and his sleeping warriors is related of that mountain, but I

have only heard of a king who is supposed to have lived at Penrhiwfer, the

fortified headland by Craig y Dinas. Iolo’s son, Taliesin Williams, says that

the Craig y Dinas of his father’s tale is the one on the very northern end of

Ystradyfodwg, near the confluence of the Mellte and the Nedd. It is a rock

formed of strata turned up almost to the perpendicular right on the river

side. Mr. Llywarch Reynolds has also heard the tale in connection with that

spot, with the place of Arthur taken by Owen Lawgoch, who often takes the

place of Arthur in the typical tale. That tale is too well-known to need

repetition here. But the “Talcen” version not only gives the essential

particulars of the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5032)

|

typical tale, but reads just like what the original tale must

have been, a description of a visit into a large chambered barrow before

cremation became universal, a time, say, before the Goidels gave shape and

body to our stock tales. There is always a passage into the “cave,” reminding

one of the “passage-graves” of the Barrow period. The Iolo tale makes the

warriors to lie down fast asleep “in a large circle, their heads outwards,

every one clad in bright armour, with their swords, shields, and other weapons

lying by them.” A megalithic grave-chamber fits the description, except that,

according to Lord Avebury, no metals are found in such graves. The typical

tale must be older than the practice of cremation. The Neolithic megalithic

chamber fits also the attendant conception of a hero imprisoned in a rock.

On regaining “Talcen y Byd” from a visit to Craig y Dinas, and standing once

more at Ffynnon Arthur, and looking at a point slightly east of north, what

do we see? Why, a colossal chair, and it is Cader Arthur (Arthur’s Chair). A

similar cavity between two peaks forms the Cader Idris of North Wales.

Looking westwards, we see the Gower peninsula, where there is an enormous

cromlech, Maen Ceti, called also “Arthur’s Stone.” Looking south, we see

Garth mountain, the southernmost extension of the “Talcen” sphere of

influence, which in Saxton’s Map is called Arthur’s buttes

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 5033)

|

hill.” With Coed Arthur, in Llantrithyd, down the Vale, I have

exhausted my list of Arthurian place-names in the district. “Arthur’s Round

Table” at Caerleon has probably no legendary basis. “Talcen y Byd” is a much

better site for it, and in confirmation of its Arthurian associations. I have

observed that the Beacons’ “chair” is hardly recognisable at Resolven. It is

best seen from “Talcen y Byd” and Carn Celyn, above Penygraig. Regarding

Cader Arthur as the centre of a circle, as we have done in connection with

another matter, the area dominated by “Talcen y Byd” forms nearly a quadrant

of that circle, and it is the people of that area most likely that recognised

in the Beacons formation the seat of a divinity called by them Arthur.

(The End).

[Note. - In Mr. D. Rhys Phillips; Welsh Librarian of Swansea, we have another

enthusiastic student of the mysteries of “Talcen y Byd.” He is a native of

its north-west slope. He has supplied us with most interesting information in

“Cambrian Notes and Queries,” published by the “Western Mail,” Ltd. He is

still, I believe, under the iron grip of the “Talcen,” and is not likely to

find much peace until he divulges at length the many secrets of the “Talcen”

which were included in his patrimony.]

|

|

|

|