.....

|

|

|

|

|

CHAPTER III.

GOVERNMENT COMMISSION OF 1846 BISHOP THIRLWALL "SUNDAY" SCHOOLS

AND STATISTICS OF LANGUAGE TAUGHT CONDITION OF DAY SCHOOLS IN ENGLISH AND

IN WELSH-WALES INEFFICIENCY OF TEACHERS WELSH LANGUAGE GENERALLY EXCLUDED

PARENTS TRUSTEES AND MANAGERS MONMOUTHSHIRE DELINQUENCY OF EMPLOYERS

OF LABOUR LEWIS EDWARDS, OF BALA IEUAN GWYNEDD SIR T. PHILLIPS

DEFECTIVE MORALS.

In 1846 the Government undertook to direct an enquiry into the state of

Education in the Principality of Wales, especially into the means afforded to

the labouring classes of an acquiring a knowledge of the English language.

The terms of the enquiry called forth the following able criticism from the

acute and learned Bishop Thirlwall of David's, well known in English literary

circles as the author of one of the Standard Histories of Greece. He acquired

sufficient knowledge of the Welsh language to be able to preach in it, and

was the only Bishop who had the courage to vote for the Disestablishment of

the Irish Church. He says in 1848:

" I think it is to be regretted that, according to the terms in which

the object of the enquiry was originally described, it was directed to be

made, not simply into 'the state of education in the principality of Wales,'

but 'especially into the means afforded to the labouring classes of acquiring

the knowledge of the EngUsh language.' I think this addition was unnecessary,

because the investigation of this point must have formed a main part of a

full enquiry into the state of education in Wales; while the putting it thus

prominently forward was attended with two unhappy effects: one is, that it

lent a handle to those who wish to represent the Commission as an engine

framed for the purpose, among others equally injurious, of depriving the

people of Wales of their ancient language. The other is, that it tended to

suggest

|

|

|

|

|

|

[CHAP. III. WALES AND HER LANGUAGE. 49

or confirm an exaggerated conception of the efficacy of schools,

in producing a change in the language of the country. This I

regard as one of the most pernicious errors that beset the subject;

and I am afraid that it prevails very extensively among persons

who have great influence over the management of schools. It

might have been thought, that a very little observation and

reflection must be sufficient to convince every one that a school,

however well conducted, must, of itself, be almost utterly powerless

for such an object, where a language taught in it for a few hours

in the day is one which the children never think in nor use at any

other time. It ought, I think, to be evident, that a general

change in the colloquial language of the country is only to be

expected from the operation of very different causes; though the

school learning may, in conjunction with them, contribute to

promote it. But the persuasion of its adequacy for the purpose is

not simply a theoretical error, but one which, so far as it prevails,

tends most seriously to obstruct the progress of good education.

For, under this impression, the managers of schools prohibit, not

only the learning of the Welsh letters, and the reading of Welsh

books, but all use of the language in school hours."

Now I wish my readers, though I fear some of those I desire to reach will

fight shy of this volume, from the very beginning, would just give due weight

to these words, "one of the most pernicious errors;" "tends

most seriously to obstruct the progress of good education." Are they the

words of an hot-headed Eisteddfodwr, or of a man of one sided culture, on

whose opinions the successors of the broken down schoolmasters of 1846, look

down with indifference from their superior vantage ground of 1891. No, they

came from the "Esgob call Tyddewi," who has left his mark in

English literature, not a Welshman, but an Englishman, who deserved to be

listened to because he knew what he was talking about, which could not be

averred in the case of nine out of ten utterances on the subject by

representative persons.

Gr

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [chap. III.

The names of the Commissioners were R. R. W. Lingen, M.A., Jelinger C.

Symons, and Henry Vaughan Johnson, each of whom furnished the Lords of the

Committee of Council on Education with a report on the district,* undertaken

by them individually. These reports contain valuable information, and will

doubtless, be again and again referred to by future historians of Wales, We

must, however, bear in mind, that they were drawn up by men to whom Wales was

a foreign country, and who were obliged to accept much evidence at

second-hand without using such discrimination as would have laid in their

power, had the sphere of their labours been in London; we must also bear in

mind that their reports shew very little evidence, that they were, in the

first place, any way adequately acquainted with the social, moral, and

intellectual state of the labouring class in England. * If they had been, I

think, they would have received the facts presented to them in Wales, with a

judgment tempered by a wider range of experience. It is true they were not

called upon to give a judgment, so much as to collect and classify evidence,

which they did in a laborious and, in some respects, admirable manner;

nevertheless, the inferences drawn from the facts were not, on the whole,

adequately representative of the reality.

The reports evoked forth quite a storm in Wales; the whole incident was

called "Bred y Llyfrau Gkision."f Sir Thomas Phillips, a Welsh speaking

Welshman the Mayor of Newport who withstood the Chartists in 1839, appeared

in the lists as the Champion of Wales, and shewed clearly that on the score

of morality, instead of Wales being, as might have

* E. W. Lingen took Carmarthen, Pembroke and Glamorgan. J. C. Symons

Cardigan, Brecknock, Radnor, and part of Monmouth. H. V. Johnson- North

Wales. + "The Treason of the Blue Books."

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III. J HER LANGUAGE. 51

been gathered from the Commissioners' report, utterly in the shade, side by

side with England though they did not say so in so many words so far as

statistics of illegitimacy are indications, six out of nine Enghsh districts,

including Yorkshire and the Northern Counties, were worse than Wales; and,

moreover, that the worst county in Wales in this respect Radnorshire is

almost entirely AngUcized in speech; Montgomeryshire and Pembrokeshire being

the next, neither of which are thoroughly Welsh counties.

Many of the Commissioners' remarks on the extremely inefficient and defective

means of intellectual and moral training would, doubtless, have applied to

some parts of England as well as to Wales. Even Wm. Howitt, the son of a man

of property, "went to a dame school, and then to one kept by a merry

little man, the baker of the village. This schoolmaster was wont to come

whistling out of his hot bakehouse to hear his pupils read, and to set them

their copies in the intervals of setting his bread."*

Events move rapidly in our days: the railway and the telegraph, and almost an

universal system of schools under efficient, trained teachers and inspectors,

are now taken as matters of course, and we almost forget how near we are

still living to the time when the machinery of education was on an altogether

different basis, when these and other developments of civilization were still

in their infancy.

Since the publication of this Report, in 1848, a new generation has had some

time to grow up, and now mainly occupies the scene of action. To many of them

it will appear almost incredible, that Wales was what it was at that time;

they will, however, bear in mind that the description of the country, given

by the Commissioners, does not illustrate an all-round

* See Records of a Quaker Family. London: Harris & Co., 1889, p. 181.

|

|

|

|

|

|

52

WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [CHAP. III.

view, but rather some aspects of it, as presented to the minds of persons who

had apparently the disadvantage of no previous common bond of sympathy or

association with the people they went to visit.

J. C. Simons and R. W. Lingen, in particular, naturally looked to the

Established Church, and its dignitaries, to perform the office of Virgil,

when he conducted Dante into purgatory, and the last mentioned Commissioner

was provided with powder and shot in the shape of introductions to the Lords

Lieutenant and the Bishops of his district. The former (J. C. S.) had letters

of introduction from the Bishop of Hereford, and a circular letter from

Connop ThirlwaU, Bishop of "St." David's.

Although, as will be seen, education has put on a new face since the time of

the Commissioners, I propose to take up some pages of this book, with extracts

from the reports, which will, I believe, not be altogether unwelcome to many

who may not readily be able to refer to the originals, and which are

necessary to my purpose of endeavouring to present materials for an

historical manual of Welsh Education in its relation to the language. The

pages refer to the 8vo. edition.

In the Government instructions issued to the Commissioners, they were

reminded of the fact that "numerous Sunday schools have been established

in Wales, and their character and tendencies should not be overlooked in an

attempt to estimate the provision for the instruction of the poor." The

Reports, accordingly, contain a mass of statistics of these schools, which

would be out of place for me to attempt to reproduce here. I will however, include

some of them bearing on the question of language, besides various remarks

made by the Commissioners, or other persons which appear worthy of attention.

For convenience sake the extracts will be grouped together

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LANGUAGE. 53

under separate headings, one of which will refer to those called Sunday

schools, and others to day schools in English speaking parts of Wales, others

to the Teachers, the condition of the school houses, School Patrons and

Managers, character of the teaching, Welsh language and literature, and

General Remarks.

FIRST DAY (SUNDAY) SCHOOL.

A prominent feature in the Report was a full amount of detail of the schools

on the first day of the week, known as Sunday Schools. Here, the Welsh

language, excluded from the day schools, found, and does still find, a place

and an important place; but the real fact remains, that in consequence,

much secular instruction was given in the way of teaching reading in that

language: and this did not escape the notice of Commissioner Symons, who

uttered a protest which has been repeated by some of the friends of Wales of

late years.

I cannot close these remarks on Sunday-schools without venturing to express

my disapproval of the practice, common alike to Church and Dissenting

schools, of allowing young children to learn and read in them. This is surely

a perversion of the object and spirit of the institution. I have frequently

seen persons occupied in teaching little children to speU and pronounce small

words, not only engrossing their time with the drudgery of elementary

instruction, but disturbing the rest of the scholars. Schools thus conducted

cease to be seminaries of relio-ious knowledge and sink into week-day schools

of the lowest class. It is a fallacy to say that no secular instruction is

given in Welsh Sunday-schools: this is secular instruction, and of the most

profitless and least spiritual kind. (Symons, p. 285.)

The Commissioner objects to the burden of teaching reading, in these schools,

which afforded the only opportunities for the mass of the population to learn

to read their mother

|

|

|

|

|

|

54 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [CHAP. III.

tongue, and yet he objects to the more preferable way of teaching it in the

day schools. If reading had not been taught there, what could have been

taught except viva voce? He embodies in his report, without comment, the

testimony of John Saunders (Independent preacher), that these schools

supplied much of the deficiency of the day schools.

This was an evil then, and it is an evil now: the proper place for secular

instruction is the day school not a gathering professedly for religious

purposes. Is it not surprising that the leaders of the people have not long

ago given due weight to the considerations which occasioned the above quoted

remarks?

What is the remedy? Plainly, nothing else than to teach Welsh children at the

day schools to read Welsh in all districts where there is a considerable

proportion of them attending Welsh classes and Welsh preaching on the first

day of the week.

Henry V. Johnson, the North Wales Commissioner, gives some very apposite remarks

on the educational effect of these schools; and although it would not be true

to say that the resources of the language in every other branch, except

theology, are meagre, the character of the demand for current Welsh

literature is very considerably modified by the fact that the terms used in

many books of a secular character are too unfamihar to make them popular. He

says

The language cultivated in the Sunday schools is Welsh; the subjects of

instruction are exclusively religious: consequently the religious vocabulary

of the Welsh language has been enlarged, strengthened, and rendered capable

o£ expressing every shade of idea, and the great mass of the poorer classes

have been trained from their childhood to its use. * * They have enriched the

theological vocabulary, and made the peasantry expert in handling that branch

of the Welsh language, but its resources in every

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LANGUAGE. 55

other branch remain obsolete and meagre, and eyen of these the people are

left in ignorance, (p. 519.)

What wonder that its resources in other branches remained obsolete, when no

further means of cultivating it were afforded.

The following two paragraphs illustrate Lingen's attitude to these schools:

They gratify that gregarious sociability which animates the Welsh towards

each other. * * The Welsh working-man rouses himself for them. Sunday is to

him more than a day of bodily rest and devotion. It is his best chance, all

the week through, of showing himself in his own character He marks his sense

of it by a suit of clothes regarded with a feeling hardly less sabbatical

than the day itself. I do not remember to have seen an adult in rags in a

single Sunday school throughout the poorest districts. They always seemed to

me better dressed on Sundays than the same class in England. (Lingen, pp. 5

and 6.)

Most singular is the character which has been developed by this theological

bent of minds isolated from nearly all sources, direct or indirect, of

secular information. Poetic and enthusiastic warmth of rehgious feeling,

careful attendance upon religious services, zealous interest in religious

knowledge, the comparative absence of crime, are found side by side with the

most unreasoning prejudices or impulses, an utter want of method in thinking

and acting, and (what is far worse) with a wide-spread disregard of

temperance whenever there are the means of excess, of chastity, of veracity,

and of fair deaUng. (do., p. 9.)

If this isolation from secular information is so prejudicial, why be so

jubilant (as will be seen further on) that there should be no secular

institution for a distinctively Welsh education, which might pave the way for

a wider scope of mental ideas.

A 1st day (Sunday) school teacher in the Welsh part of Caio hundred,

Carmarthenshire, sent the learned Commissioner

|

|

|

|

|

|

56

WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. CHAP. III.]

a letter, from which the following, verbatim et literatim, is

extracted:

I am very please to take little trouble to answer your letter about the

Sunday Schools, in hope that your Searching about the Daily and Sunday

Schools, will come to good consequence to the Welsh Nation.

Our Creator make many of them a People of Strong Abilities, and a possessors

of various talents, but because their ignorance Spend their time in poverty

to get their living in Slavery as a pig and his snout in the ground they got

no advantage to make use of their abiUties in defect of learning and

knowledge. But Some of the young people are under good education, the Children

of the Noblemen and Gentlemen farmers but the greater part of them in Towns:

and in the countrys one here and one there. The major part of the welchmen,

not knoweth in what quarter of the world they live? this thing I think is

very true.

In the time ago riseth up some Excellent people in Philosophy and Theology

among the welch Nation as one of the *welch Poet say's about one of them,

called The Eeverend Mr. Rowlands Llangaetho,

Talentau ddeg f e roddwyd iddo

Pe'i marchnattodd hwy yn iawn Ae* o'r deg fe'i gwnaeth hwy'n gannoedd Cyn

maihludo 'i haul brydnhawn.

I hope that you'll not be angry with me, because I have on my mind to desire

on you, Sir, to give me a httle presant, that is, the Map of the land of

Canaan, (do., pp. 185 and 186.)

At Llanelly, in connection with the Capel Als School (Independent), some of

the parents objected to their children "being taught Welsh on

Sundays." This objection would now be scarcely so likely to occur.

* William Williams, Pantycelyn. The stanza is given as printed, but I am

inclined to think that the errors in the Welsh spelling were due to the

compositor or the transcriber.

|

|

|

|

|

|

[chap. III. HER LANGUAGE. 57

The following observation is undoubtedly just:

[Grilead School, wholly Welsh]. Eeadiness and propriety of expression, to an

extent more than merely colloquial, is certainly a feature in the

intellectual character of the Welsh. (Lingen, p. 136.)

J. C. Symons says of the Dissenting schools, that the routine is admirable,

and of the "Church Sunday Schools," they want life. The whole

system is spiritless and monotonous and repulsive instead of attractive to

children;" and in the way of general remarks

I have heard very curious and recondite inquiries directed to solve even

pre-Adamite mysteries in these schools. The Welsh are very prone to mystical

and pseudo-metaphysical discussion, especially in Cardiganshire. The great

doctrines and moral precepts of the Grospel are, I think, too little taught

in Sunday Schools. They are more prone to dive into abstract and fruitless

questions upon minute incidents, as well as debatable doctrines, as for

example, who the angel was that appeared to Balaam, than to illustrate and

enforce moral duties or explain the parables. (Symons, p. 285.)

Somewhat contrasting with the remarks of Lingen on such schools are those of

the third Commissioner, H. V. Johnson, he says:

As the influence of the Welsh Sunday school decreases, the moral degradation

of the inhabitants is more apparent. This is observable on approaching the

English border. * «> *

The humble position and attainments of the individuals engaged in the

establishment and support of Welsh Sunday schools enhances the value of this

spontaneous effort for education; and however imperfect the results, it is

impossible not to admire the vast number of schools which they have

estabhshed, the frequency of the attendance, the number, energy, and devotion

of the teachers, the regularity and decorum of the proceedings, and the

striking and permanent effects which they have produced upon society, (p.

519.)

H

|

|

|

|

|

|

58 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [OHAP. HI.

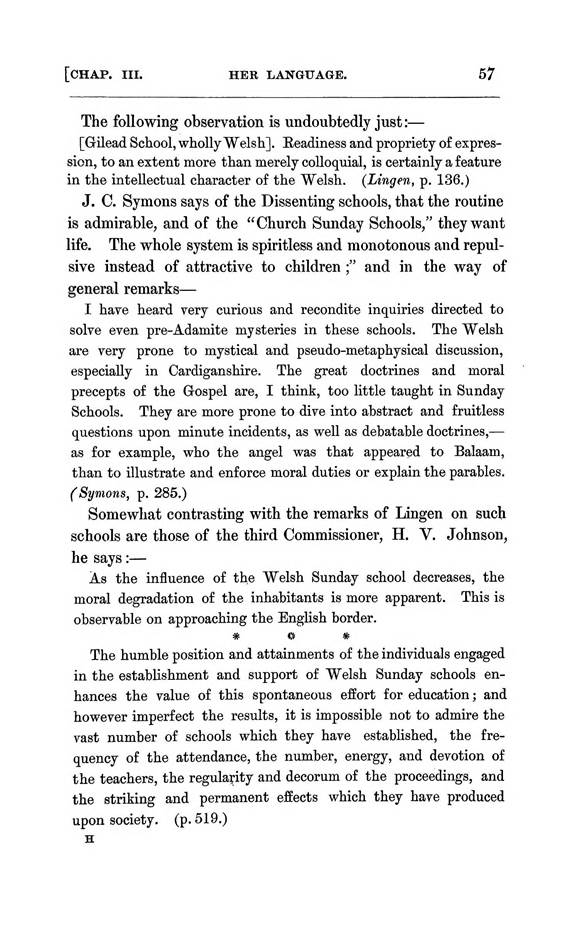

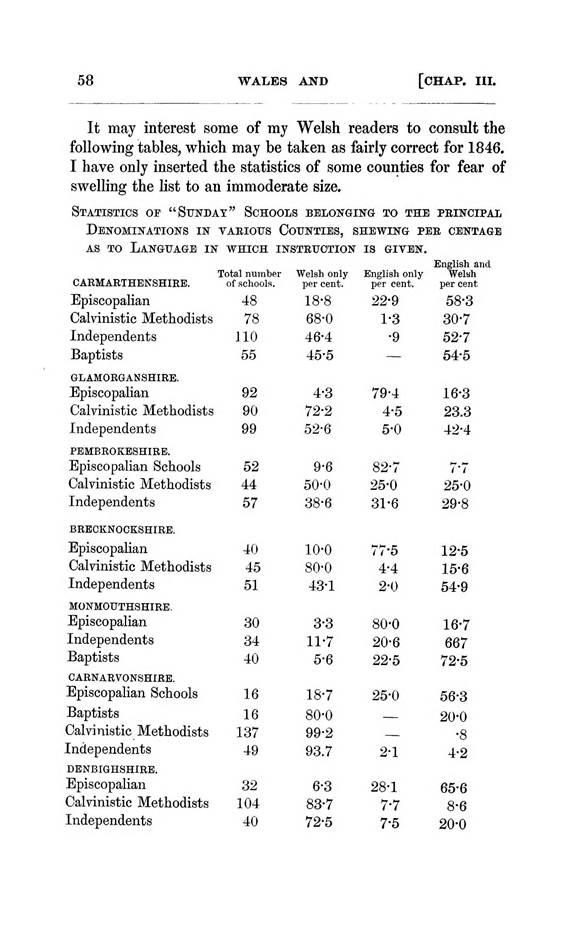

It may interest some of my Welsh readers to consult the following tables,

which may be taken as fairly correct for 1846. I have only inserted the

statistics of some counties for fear of swelling the list to an immoderate

size.

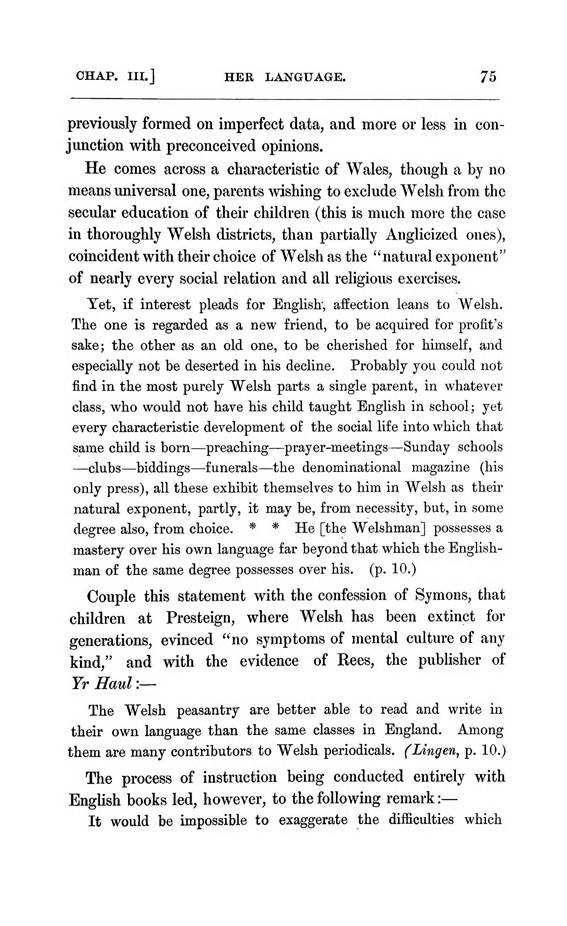

Statistics oe "SriTDA'r" Schools BULOifGiNG to the peincipal

DBjrOMIITATIONS IN VAEIOITS CoTOfTIBS, SHEWING PEE CBNTAGB

AS TO Language in which insteuotion is giten.

English and

rotal number

Welsh only

English only

Welah

CAEMARTHEKSHIRE.

of .schools.

per cent.

per cent.

per cent

Episcopalian

48

18-8

22-9

58-3

Calvinistic Methodists

78

68-0

1-3

30-7

Independents

no

46-4

9

52-7

Baptists

55

45-5

54-5

glamoeganshire.

Episcopalian

92

4-3

79-4

16-3

CaMnistic Methodists

90

72-2

4-5

23.3

Independents

99

52-6

5-0

42-4

PBMBEOKESHIEB.

Episcopalian Schools

52

9-6

82-7

7'7

Calrinistic Methodists

44

50-0

25-0

25-0

Independents

57

38-6

31-6

29-8

BRECKNOCKSHIRE.

Episcopalian

40

10-0

77-5

12-5

Calvinistic Methodists

45

80-0

4-4

15-6

Independents

51

43-1

2-0

54-9

monmouthshiee.

Episcopalian

30

3-3

80-0

16-7

Independents

34

11-7

20-6

667

Baptists

40

5-6

22-5

72-5

CARNARVONSHIRE.

Episcopalian Schools

16

18-7

25-0

56-3

Baptists

16

80-0

20-0

Calvinistic Methodists

137

99-2

8

Independents

49

93.7

2-1

4-2

DENBIGHSHIRE,

Episcopalian

32

6-3

28-1

65-6

Calvinistic Methodists

104

83-7

7-7

8-6

Independents

40

72-5

7-5

20-0

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. HI.] WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE].. 59

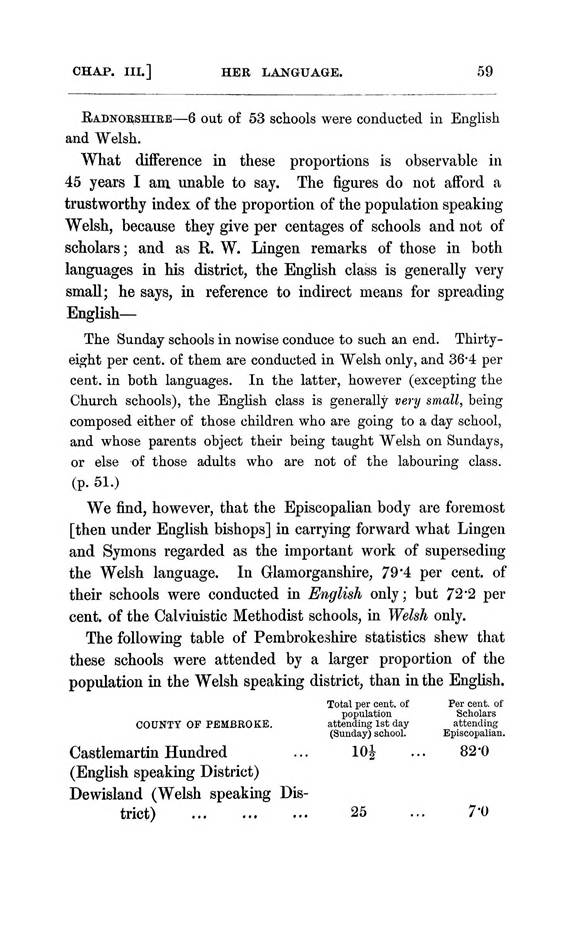

Eadnoeshibe 6 out of 53 schools were conducted in English and Welsh.

What difference in these proportions is observable in 45 years I am. unable

to say. The figures do not afford a trustworthy index of the proportion of

the population speaking Welsh, because they give per centages of schools and

not of scholars; and as R. W. Lingen remarks of those in both languages in

his district, the English class is generally very small; he says, in

reference to indirect means for spreading English

The Sunday schools in nowise conduce to such an end. Thirty-eight per cent,

of them are conducted in Welsh only, and 36"4 per cent, in hoth

languages. In the latter, however (excepting the Church schools), the BngUsh

class is generally very small, being composed either of those children who

are going to a day school, and whose parents object their being taught Welsh

on Sundays, or else of those adults who are not of the labouring class. (p.

51.)

We find, however, that the Episcopalian body are foremost [then under English

bishops] in carrying forward what Lingen and Symons regarded as the important

work of superseding the Welsh language. In Glamorganshire, 79'4 per cent, of

their schools were conducted in English only; but 72 "2 per cent, of the

Calvinistic Methodist schools, in Welsh only.

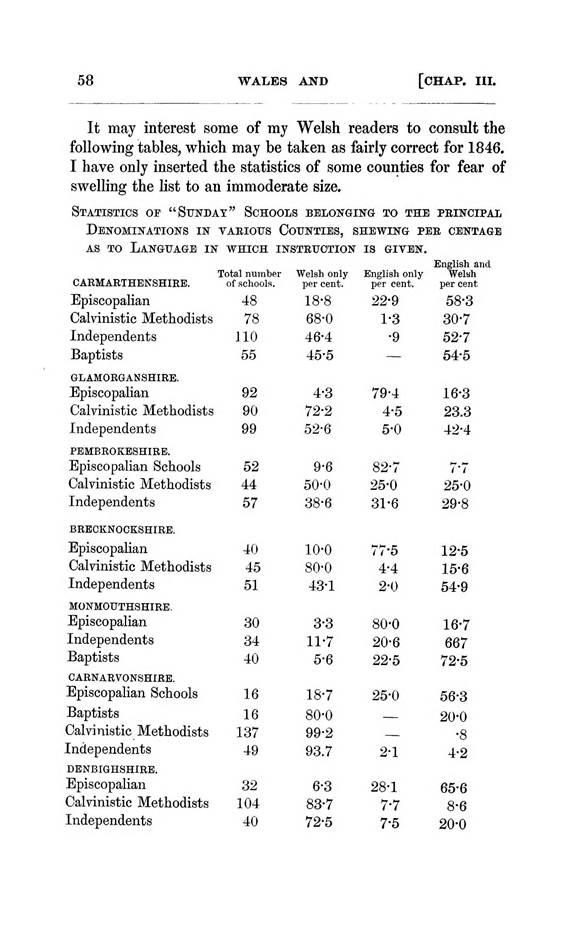

The following table of Pembrokeshire statistics shew that these schools were

attended by a larger proportion of the population in the Welsh speaking

district, than in the English.

COIINTT OF PEMBROKE.

Total per cent, of

population attending 1st day (Sunday) school.

Per cent, of

Scholars

attending

Episcopalian.

Castlemartin Hundred

lOj

82-0

(English speakmg District)

Dewisland (Welsh speaking District)

25

7-0

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 WALES AND [OHAP. III.

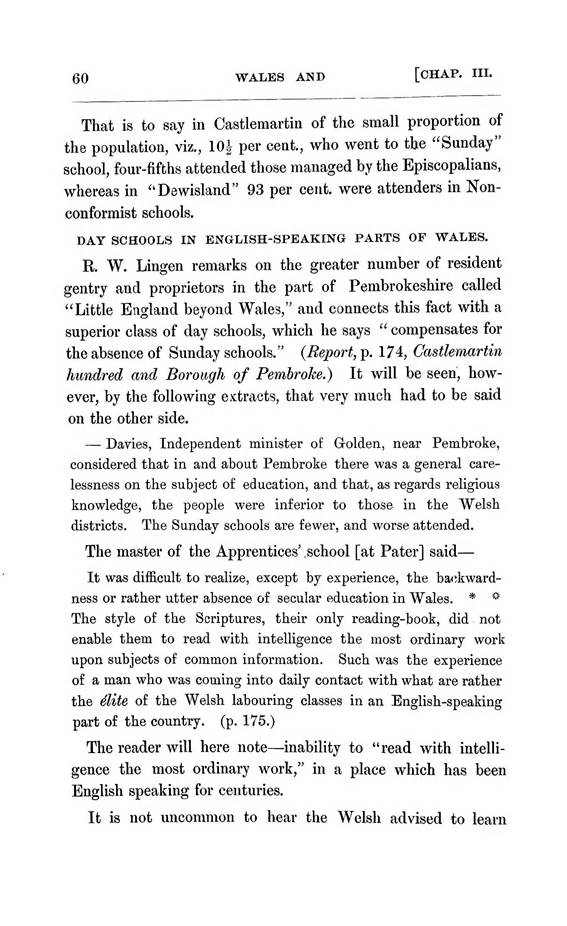

That is to say in Castlemartin of the small proportion of the population,

viz., 10| per ceat., who went to the "Sunday" school, four-fifths

attended those managed by the Episcopalians, whereas in "Dewisland"

93 per cent, were attenders in Non-conformist schools.

DAY SCHOOLS IN ENGLISH-SPEAKING PARTS OF WALES.

R. W. Lingen remarks on the greater number of resident gentry and proprietors

in the part of Pembrokeshire called "Little England beyond Wales,"

and connects this fact with a superior class of day schools, which he says

" compensates for the absence of Sunday schools." {Report, p. 174,

Castlemartin hundred and Borough of Pembroke.) It will be seen, however, by

the folio wiag extracts, that very much had to be said on the other side.

Davies, Independent minister of Grolden, near Pembroke, considered that in

and about Pembroke there was a general carelessness on the subject of

education, and that, as regards religious knowledge, the people were inferior

to those in the "Welsh districts. The Sunday schools are fewer, and

worse attended.

The master of the Apprentices' school [at Pater] said

It was difficult to realize, except by experience, the bai'-kwardness or

rather utter absence of secular education in Wales. * * The style of the

Scriptures, their only reading-book, did not enable them to read with

intelligence the most ordinary work upon subjects of common information. Such

was the experience of a man who was coming into daily contact with what are

rather the ilite of the Welsh labouring classes in an English-speaking part

of the country, (p. 175.)

The reader will here note inability to "read with intelligence the

most ordinary work," in a place which has been English speaking for

centuries.

It is not uncommon to hear the Welsh advised to learn

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LANGUAGE. 61

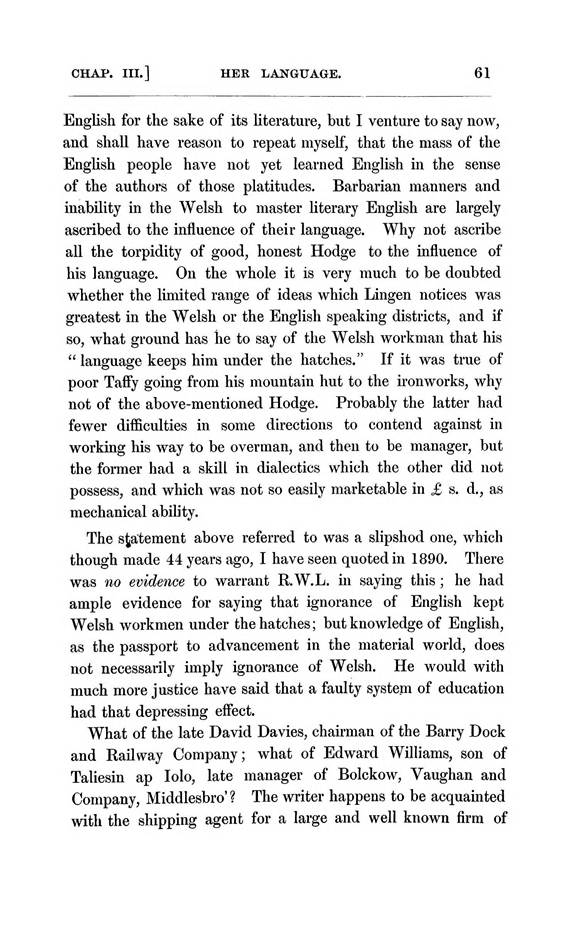

English for the sake of its literature, but I venture to say now,

and shall have reason to repeat myself, that the mass of the

English people have not yet learned English in the sense

of the authors of those platitudes. Barbarian manners and

inability in the Welsh to master literary Enghsh are largely

ascribed to the influence of their language. Why not ascribe

all the torpidity of good, honest Hodge to the influence of

his language. On the whole it is very much to be doubted

whether the limited range of ideas which Lingen notices was

greatest in the Welsh or the English speaking districts, and if

so, what ground has he to say of the Welsh workman that his

" language keeps him under the hatches." If it was true of

poor Tafly going from his mountain hut to the ironworks, why

not of the above-mentioned Hodge. Probably the latter had

fewer difficulties in some directions to contend against in

working his way to be overman, and then to be manager, but

the former had a skill in dialectics which the other did not

possess, and which was not so easily marketable in £ s. d., as

mechanical ability.

The statement above referred to was a slipshod one, which though made 44

years ago, I have seen quoted in 1890. There was no evidence to warrant

R.W.L. m saying this; he had ample evidence for saying that ignorance of English

kept Welsh workmen under the hatches; but knowledge of Enghsh, as the

passport to advancement in the material world, does not necessarily imply

ignorance of Welsh. He would with much more justice have said that a faulty

system of education had that depressing eSect.

What of the late David Davies, chairman of the Barry Dock and Railway

Company; what of Edward Williams, son of Taliesin ap lolo, late manager of

Bolckow, Vaughan and Company, Middlesbro'? The writer happens to be

acquainted with the shipping agent for a large and well known firm of

|

|

|

|

|

|

62

WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. CHAP. III.]

colliery proprietors, who remarked not long ago, " While I am speaking to

you I am translating from Welsh (mentally) into English;" at any rate

that fact did not disqualify him for a responsible position.

Pursuing the point further

"The non-comprehension of what they read is by no means confined to the

children who speak "Welsh, and read EngUsh; it prevails also amongiSt

those of whom English is the mother tongue. The reason is that the Enghsh

they read is not the English they talk. * * * I found children who read

fluently, constantly ignorant o£ such words, as ' obssrre,' ' conclude,' '

reflect,' ' psrceive,' ' refresh,' &c." (Symons, p., 255, 256.)

He rightly observes that one reason of this is that English children are

Anglo-Saxon born, while the books use words of Norman-French or Latin

derivation. It does not seem to have occurred to him that Welsh children

receiving information on an abstract subject through the medium of Welsh

would have, in this respect, an advantage over English ones of the working

class, in that little or no time need be wasted in drilling the meaning of

the words into them.

A schoolmaster's wife in the Eaglish part of Radnorshire informs him

The parents do not wish it [questioning on mental teaching]: they do not send

their children to day-schools to get rehgious, or, in fact, "'any mental

education; they send them purely from a money motive, that they may advance

themselves more easily in life; and to this end, reading English, writing,

and ciphering, are esteemed certain and sufficient means. {Symons, p. 242.)

At Presteign, Radnorshire, endowed school: " The children evinced no

symptoms of mental culture of any kind."

At Buttington, Montgomery (H. W. Johnson's report): AU were ignorant of

Scripture; and a scholar in the first class believed that St. Matthew wrote

the History of England.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LANGUAGE. 63

At Bersha/m, in the county of Denbigh, scholars were questioned on outlines

of Scripture History: " They were ignorant of everything."

Ignorance of English was not confined to teachers who were natives of Wales:

the master at Holt, Denbighshire, " speaks English with a broad Cheshire

dialect, and very ungrammatically."

At Northop, Flintshire:

English is spoken in this part of the parish of Northop; but notwithstanding

this, the children recently admitted could not tell me which was their right

hand and which their left. (p. 499.) SCHOOL-HOUSES AND SUBEOUNDINGS.

Very little comment is needed from me under this or the succeeding head, the

paragraphs given, will, it is hoped, elucidate the History of Wales in the

second quarter of the nineteenth century.

The school was held in a room, part of a dwelling-house; the room was so

small that a great many of the scholars were obliged to go into the room

above, which they reached by means of a ladder, through a hole in the loft;

the room was lighted by one small glazed window, half of which was patched up

with boards; it was a wretched place; the furniture consisted of one table,

in a miserable condition, and a few broken benches; the floor was in a very

bad state, there being several large holes in it, some of them nearly half a

foot deep; the room was so dark that the few children whom I heard read were obliged

to go to the door, and open it, to have sufficient light. (Lingen, p. 21.)

This school is held in the mistress's house. I never shall forget the hot,

sickening smell, which struck me on opening the door of that low dark room,

in which 30 girls and 20 boys were huddled together. It more nearly resembled

the smell of the engine on board a steamer, such as it is felt by a sea-sick

voyager on passing near the funnel, ('do., p. 25.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

64 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [CHAP, III.

This school is held in a ruinous hovel of the most squalid and miserable

character; the floor is of bare earth, full of deep holes; the windows are

all broken; a tattered partition of lath and plaster divides it into two

unequal portions; in the larger were a few wretched benches, and a small desk

for the master in one corner; in the lesser was an old door, with the hasp

stiU upon it, laid crossways upon two benches, about half a yard high, to

serve for a writing-desk! Such of the scholars as write retire in pairs to

this part of the room, and kneel on the ground while they_write. On the floor

was a heap of loose coal, and a litter of straw, paper, and all kinds of

rubbish. The Vicar's son informed me that he had seen 80 children in this

hut. In summer the heat of it is said to be suffocating; and no wonder, (do.,

p. 25, 26.)

This school is held in the church. I found the master and four little

children ensconced in the chancel, amidst a lumber of old tables, benches,

and desks, round a three-legged grate full of burning sticks, with no sort of

funnel or chimney for the smoke to escape. It made my eyes smart till I was

nearly blinded, and kept covering with ashes the paper on which I was

writing. How the master and children bore it with so little apparent

inconvenience I cannot tell, (do., p. 26.)

The schoolroom was originally a cow-shed, converted into a schoolroom without

any attempt even to mend the paving of the floor, which was weU worn and so

uneven that the rough benches in it were propped up by large stones; the

walls were of mud, the roof of decayed thatch, without any attempt at a

ceiling; and there were only two small windows at each end, affording little

light in the middle of the place. Each child had a book, and nearly all were

reading aloud, each by himself. The master, a poor half-starved looking man,

came out rod in hand to met us. Our visit, he said, was not unexpected, as he

heard we were going about. (Symons, pp. 274, 275.)

Until the winter was far advanced, although the weather was

|

|

|

|

|

|

[chap. III. HER LANGUAGE. 65

most severely cold and damp, fires were rarely found in these desolate places

in Cardiganshire, p. 239.

I found the schoolroom used as a receptacle for churning materials,

gardening-tools, and sacks of flour. * * Of these [49] only 14 knew the

alphabet.

At Mydrolin, the room in which the school is held is a low, dark, damp building,

erected partly of stone and partly of mud, and thatched with straw,

altogether unfit for a place to conduct a school in. The floor of it, on the

day I visited it, was completely covered with mud and water, worse than some

places on a country road on a wet day. (Symons, p. 277.)

A Radnorshire school The door guarded by a pig!

Having been assured it was at the church, I tried in vain to gain access to

the building itself; and as I was turning away in despair, I heard the hum of

a school in a wooden hut, in the last state of decay, with extensive plains

of mud in front, and a pig asleep at the door. The thatch was mouldering

away, and there was scarcely a whole board in the entire building. Having

passed through a sepulchral sort of kitchen, I obtained access through it to

the school-room an inner room, or rather a slip of one, in which it was not

easy to steer one's way safely through the beams and rafters by the dim light

of two minute windows, one at either end. A handful of children were ranged on

rude seats along the walls. [Nantmel, English speaking district.] (Symons, p.

272.)

THE HEADMASTERS DESCRIBED.

The present average age of teachers is upwards of 40 ye3,rs; that at which

they commenced their vocation upwards of 30; the number trained is 12-5 per

cent, of the whole ascertained number; the average period of training is 7-30

months; the average income is £22 10s. 9d. per annum; besides which, 16-1 per

cent, have a house rent-free. {Lingen, p. 53.)

Of course, these figures apply to his district Carmarthen, Glamorgan and

Pembroke. Imagine the schools of Wales, in

|

|

|

|

|

|

WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE].

[OHAP. III. 1891, being staffed with teachers that is, head masters and

mistresses (for in those days paid assistants were so few as to be unlikely

apparently to affect the return), whose average income was only £22 10s. 2d.

per year, and that only 16"1 per cent, lived rent free. In North Wales

the gross average income from all sources, so far as returns were given, was

£26 19s. 2d.

The list of previous occupations of these so called teachers presents a

miscellaneous medley, affording room for reflection e.g., it includes clerks,

carpenters, cooks, drapers, milliners, farmers and farm servants, labourers,

mariners, and married women, whereas only one in eight had served any

apprenticeship to it. Think, moreover, of a private school, " somewhat

superior," when, after attempts to fix a charge of 10s. a quarter, it

was found necessary to make a separate bargain for each child, according to

the means and willingness of the parents.

J. C. Symons remarks that "the established belief for centuries has been

that it requires no training at all" to be a schoolmaster; but even in

those early days there was a certain amount of negative uniformity among the

masters, as indicated by the following, in which it transpires that they were

usually found doing anything but teaching, while in this instance

"blindman's buff" supplied the place of a fire.

It is singular that in three or four instances only have I found a

schoolmaster occupied in teaching on suddenly entering a school of the common

class. I have far oftener found them reading an old newspaper, writing a

letter or a bill, probably for some other person, reading a "Welsh

magazine, or doing nothing of any sort. At one school, near Aberystwyth, I

was attracted, while passing along the road, by the boisterous noise in

school, and on entering it found the whole of the scholars playing at

blindman's-buff, or some similar game, though the dust and confusion

prevented me

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. Ill,] HER LANGUAGE. 67

from ascertaining what it was. I found that the master was absent, and had

gone to warm himself at a neighbouring cottage; and on arriving he said that

he told them "to have a bit of play, just to warm them."

The following paragraph refers to the usual equipraent of schools:

A Welsh schoolmaster of the ordinary description thinks himself well supplied

if he is provided with two long tables and one short table, two or three

forms for the children, a chair for himself, a score of Bibles, slates, and

Vyse's spelling books, a few copy books, plenty of primers, two or three

Walkinghame's Tutor's Assistant; an old newspaper, a rod, and if it be

winter, a heap of peat in the corner, complete the sum of his wants, and of

the recognized requirements of the scholars. The area of the room is often

ludicrously insufficient, and at other times uncomfortably large. (Symons, p.

240.)

H. Vaughan Johnson, after referring to mere youths being put in charge of

wholly undisciplined and ignorant scholars, says, still worse results are

occasioned by employing aged persons and cripples, e.g. the master at Kilkin,

Flintshire, was a miner, disabled by ill health.

I will however summarize some of the notable features of the schoolmasters in

his district in short sentences following the name of the place they belonged

to. Penbleddtn Income, £19. Apparently induced to accept

these terms by the loss of one eye. Pbntrecaehelyg (Vale of Clwyd) A

quarryman fractured

his leg. Determined to commence teaching, but studied

Latin and Greek! for nine months instead of undergoing any

training. Llanbrynmair, Mont. A village shopkeeper children

laughed at everything that was said to them. Penygroes, Mont. Untrained,

made innumerable errors in

catechizing the scholars, pronounced wild weeld, region,

ragion.

|

|

|

|

|

|

68 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [OBU.P. III.

Holt, Denbigh. Englishman, spoke very ungrammatically, when he thought a blunder

was committed, corrected it by committing another.

Halkin, Flint. Englishman, says whoole for whole, han for an.

Aberfpraw Free School. Master assured H. V. Johnson that the children

understood nothing of what they read in English, but he attempts no kind of

explanation.

"Church" School, Ruthin. An Englishman, with no system of

interpretation. Scholars all Welsh. His questions few, slowly conceived, and

commonplace.

DoLwrDDELEN, Carn. Master 54. Previously cattle dealer and drover. Scholars

positively laughed at his attempting to control them.

Overton (Enghsh Flintsh.) Free School. ^Only 2 out of 6 who profess to know

arithmetic, could work a plain sum in addition.

Epailrhqd, Denbigh. Formerly a farm servant. His method of teaching grammar

is unusual. He reads the book and the children repeat after him, as if making

responses at church.

"Church" School, Llandysilio. A mere boy (19), untrained, knew

but little Welsh, while only one scholar knew English.

"Church School," Llanynys, Denbigh. Pupils stated that Pharaoh was

king of Israel, and the master commended them, saying, "very good."

Called British, Brutish, and the like.

Grespord (English part of Denbigh). Master in a public-house at 10 a.m.;

boys playing with all their might. Afternoon, master again absent, boys

playing at horses.

Llanpynydd, Flint. Master did not attempt to suppress the tumult, uproar

and disorder prevailing during the visit. Commissioner feared lest a general

fight should ensue before examination was finished.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. Ill,] HER LANGUAGE. 69

"St." David's "Church" School, Festiniog. Continual

uproar. Girls sweeping the school floor unbidden, and struck the heads of the

boys with a broom while the examination was going on.

Rhyl. Had taught for four months only. Was extremely deaf. Cannot detect

mistakes nor ascertain when scholai-s are making a disturbance.

Llandyrnog "Church" School Aged and infirm. Appears to have had

no education.

Rhiwlas, Llansilin. Formerly a blacksmith, for father he smAfayther and

gounzillor for counsellor.

"Church" School, Ruthin. Master trained for eight months at

Westminster. The folio w^ing extract is really of too outre a character to be

condensed:

Neither master nor scholar appeared to have any idea of manners or disciphne.

While I examined the school, all remained sitting, including the master; I

could not do the same, as there was no seat left. The boys sat lolling

luxuriously with their hands in their pockets, and answered or not, just as

they felt inclined. In the mean time all business was abandoned by the rest,

who collected themselres in groups, looking on and talking. One or two

monitors amused themselves by wandering about, striking the younger boys, but

indiscriminately, and with no useful object in view. I could with difSculty

walk across the room without catching the saUva which the boys were spitting

in all directions not through disrespect, but from habit.

Please note The Commissioner standing, boys lolling luxuriously, amusements

of the monitors, the "difficulty" of walking across the room,

&c.

British and Foreign School. Ruthin. One of the best in North Wales. Master

inspired the pupils with a desire for knowledge, but neglected discipline.

The Commissioner

|

|

|

|

|

|

70 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. CHAP. III.]

regrets that scholars so intelligent, and making such progress in all subjects,

should not be taught manners. Few schools in North Wales were found destitute

of a cane or birch rod.

PATRONS AND MANAGERS.

A large class of the promoters of schools were unqualified to "select

masters or superintend institutions." For instance, the promoters of a

British school of great reputation, represented in high terms the extent of

instruction and attainments of the pupils, but when examined, in grammar, it

was found that the pupils had never heard of the singular or plural number.

H. V. J. next describes how the children are specially coached up to answer

questions gone through beforehand, so that when "the gentry visit

them" * * "they gain great approbation and obtain the credit of

being excellent institutions."

Speaking of schools richly supported by the "clergy and wealthy

classes," H. V. Johnson says

The visitors and promoters of such schools appear to have overlooked the

defect which lies at the root of all other deficiencies the want of books

expressly adapted, and of teachers properly qualified, to teach English to

Welsh children. The majority appear conscious (sic) that English may remain

an unknown language to those who can read and recite it fluently; others have

frequently assured me that Welsh parents would not endure any encroachment

upon their language an argument which would seem to imply great ignorance

of the poor among their countrymen, who, as I have already stated, insist on

having English only taught in the day-schools, and consider all time as

wasted which is spent in learning Welsh, (pp. 477, 478.)

The complaints have been generally made by persons among the higher classes,

who, through neglect, have aUowed their schools to become extinct, or,

through misapprehension of the character

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LANGtTAGE. 71

and temper of the inhabitants, have failed to adapt the style and subjects of

instruction to the requirements of those whom they professed to teach, (p.

486.)

A fatal delusion has misled the promoters of schools in North Wales. They

have supposed that, if children make use of the Bible as a handbook to learn

reading from the alphabet upwards, and if catechisms be carefully committed

to memory, the narratives and doctrines therein contained must be impressed

on their understandings and affections, (p. 500.)

Bear in mind, good reader, that we are now adverting to persons who were the

victims of a "fatal delusion," and permitted in the schools under

their care a defect which lay at the "root of all other

deficiencies." Did they belong to the lower stratum of society? No; we

may reasonably suppose that some of them had received an English University

education, and yet in the year 1891 there is evidence that exactly the same

defects would be found in the schools under the care of their successors, had

not they in some respects reaped the benefit of other men's labours; and in

one important matter the want of books expressly adapted for teaching

English to Welsh children, the "clergy and wealthy classes" are

content, and many of them very well content, with the system which the

Commissioner of 1846 condemned, which degrades Welsh without properly

elevating English; while they appear to receive with stolid indifference any

outcry for a more reasonable and more natural method.

In the discharge of his duty the North Wales Commissioner collected some

valuable evidence about endowments and school fiinds which it would be out of

place to reproduce, at any great length, in this book. In North Wales the

endowments exceeded £4,000, excluding a large amount under litigation. Of

this a considerable proportion was misapplied.

At Bryneglwys, Denbigh, for instance, there was an endow-

|

|

|

|

|

|

72 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [CHAP. III.

ment, but the school was closed. The clergyman appointed himself master,

i.e., pocketed the stipend of one.

Llanerftl, Mont. A valuable endowment. One of the trustees farms the

charity estate without accounting for rents, in return for which he professed

to act as schoolmaster. Had eight scholars, and was frequently absent.

Outbuildings out of repair and occupied by geese, hatching. RuABON Grammar

School. Valuable endowment of £100 per year.

I found the school-room, which would accommodate 81 scholars, partly filled

with coals, and the remainder used as a lumber-room, being covered with

broken chairs and furniture. The glass of the windows was broken, and the

room neglected and filthy in the extreme. The lumber and dirt appeared to

hare been accumulating for several months, and, except some tattered books,

without covers, in the window-seats, there was no^vestige of the school

vi'hich is said to have been held there. Deythur, Montgomery Endowment

reduced by Law Suits; £88 paid to the nominal master, a clergyman; school

conducted by an usher, previously an agricultural labourer, and was inferior

to the average of the lowest schools in North Wales. Pupils understood more

EngUsh than Welsh.

Here is plain speaking about supporters of National Schools, giving a notable

illustration of pleidgarwch or sectyddiaeth in the Establishment.

In addition to the above-mentioned abuses, it is important to state that it

is a practice in North "Wales for the trustees of endowed schools which

are not absolutely connected with the Established Church, to allow waste and

dilapidation, and to neglect to visit and examine the scholars, with the

professed object of inducing their parishioners to consent to have the

schools united with the National Society. I allege this upon the authority of

their own statements, in which the practice and the motives of it were

avowed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

[CHAP. III. [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 73

We can imagine such pious trustees holding up their hands in holy horror at

the wrangling in the denominational literature of the benighted Dissenters; for

this, it is evident they had but two remedies; one was to extinguish the

Welsh language, the other to drive the wanderers back to the bosom of their

Mother Church.

H. V. Johnson finds that out of the funds of 517 schools the rich subscribe

£5,675, and the amount raised by the poor is £7,000, adding

It is important to observe the misdirection of these branches of school

income, and the fatal consequences which ensue.

The wealthy classes who contribute towards education belong to the

Established Church; the poor who are to be educated are Dissenters. The

former will not aid in supporting neutral schools; the latter withhold their

children from such as require conformity to the Established Church. The

effects are seen in the co-existence of two classes of schools, both of which

are rendered futile the Church schools supported by the rich, which are

thinly attended, and that by the extreme poor; and private-adventure schools,

supported by the mass of the poorer classes at an exorbitant expense, and so

utterly useless that nothing can account for their existence except the

unhealthy division of society, which prevents the rich and poor from

co-operating, (p. 511.)

The report further speaks of parents purchasing exemptions from the rules

requiring conformity in religion by payment of a small gratuity, to increase

the "slender pittance" of the master of expulsion where poor

parents held out of a compromise in other cases, the children being

cautioned by the parents not to believe the Catechism, and to return to the

"paternal chapels" as soon as they have finished schooling of the

"inexpedience" of such a system being not yet apparent, except to a

few; and moreover when speaking of private adventure, and dame schools of an

utterly worthless character,

|

|

|

|

|

|

74 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [OHAP. Ill,

"tliat nothing can account for their existence except the determination

on the part of Welsh parents to have their children instructed without

interference in matters of conscience," while such schools exhaust the

greater part of the £7,000 contributed by the poor towards education.

The intellectual results produced by the present class of Church

schoolmasters, reduced as they are to such extremities, has been already seen

in the ignorance of scholars, not only respecting the distinctive doctrines

of the Church, but of the first element of Christianity, (p. 512.)

H. V. J. complains respecting indiiference as to education on the part both

of parents and children. After alluding to the fact that many scholars walked

eight miles a day, he very justly remarks, considering the value of the

instruction, they cannot be expected to " expend more time in an

occupation so unprofitable."

WELSH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE.

In dealing with the Welsh language and literature, as might be expected, the

three Commissioners were very largely dependent for information upon other

persons.

Lingen and Symons pass by the phenomena of existing Welsh literature with

very scant notice indeed. Johnson, on the other hand, makes what appears to

be an honest attempt to analyze its character, though he was far from doing

it justice. Lingen and Symons adopted a directly antagonistic position to the

existence of the language. Johnson stood more on neutral ground: the two

former, however, obtained the ear of the Government, and not long after the

publication of the report Lingen was given the important post of Secretary to

the Committee of Council on Education, and it may well be beheved that his

subsequent attitude towards Welsh education was very much influenced by the

judgment he had

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LAJi^GUAGE. 75

previously formed on imperfect data, and more or less in conjunction with

preconceived opinions.

He comes across a characteristic of Wales, though a by no means universal

one, parents wishing to exclude Welsh from the secular education of their

children (this is much more the case in thoroughly Welsh districts, than

partially Anglicized ones), coincident with their choice of Welsh as the

"natural exponent" of nearly every social relation and all

religious exercises.

Tet, if interest pleads for English, afEection leans to Welsh. The one is

regarded as a new friend, to be acquired for profit's sake; the other as an

old one, to be cherished for himself, and especially not be deserted in his

decline. Probably you could not find in the most purely Welsh parts a single

parent, in whatever class, who would not have his child taught English in

school; yet every characteristic development of the social life into which

that same child is born preaching prayer-meetings Sunday schools

clubs biddings funerals the denominational magazine (his only press),

all these exhibit themselves to him in Welsh as their natural exponent,

partly, it may be, from necessity, but, in some degree also, from choice. * *

He [the Welshman] possesses a mastery over his own language far beyond that

which the Englishman of the same degree possesses over his. (p. 10.)

Couple this statement with the confession of Symons, that children at

Presteign, where Welsh has been extinct for generations, evinced "no

symptoms of mental culture of any kind," and vidth the evidence of Rees,

the publisher of Yr Haul:

The Welsh peasantry are better able to read and write in their own language

than the same classes in England. Among them are many contributors to Welsh

periodicals. (Lingen, p. 10.)

The process of instruction being conducted entirely with English books led,

however, to the following remark:

It would be impossible to exaggerate the difficulties which

|

|

|

|

|

|

76 WALES

AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [CHAP. III.

this diversity between the language in which the school-books are written and

the mother-tongue of the children presents. In proportion as the teacher

adheres to English, he does not get beyond the child's ears; in proportion as

he employs Welsh, he appears to be superseding the most important part of the

child's instruction. How and where to draw the line how to convey the

principles of knowledge through the only medium in which the child can

apprehend them, yet to leave them impressed upon its mind in other terms, and

under other forms how to employ the old tongue as a scaffolding, yet to

leave no trace of it in the finished building, but to have it, if not lost,

at least stowed away all this presupposes a teacher so thoroughly master of

the subjects which he is going to teach, and also of two languages most

dissimilar in genius and idiom, that he can indifferently represent his

matter with equal clearness in one as in the other. (Lingen, p. 52).

Why should he be so anxious to leave "no trace" of the old tongue,

to which he is a stranger, in the "finished building" of the completed

education of the youth in Wales. A person entrusted with such a responsible

post should have seen at once that English per se is not "the most important part of the child's

instruction." Many thousands of English agricultural labourers have

learned English from their early childhood, but they are still "under

the hatches," and their intelligence remains comparatively undeveloped.

In 1847, as now, the parents of Welsh children were eager to have them taught

English almost without exception, and being themselves ignorant, were quite

content with the mentally wasteful way which is continued down to the present

day of having all school-books solely in English.

We see in the above extract how the Commissioner appears nearly to come to

the conclusion of the Welsh Utilization Society, that it would be best to

employ bilingual books, but he shrinks from expressing it, evidently from the

fear that

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 77

while the children are learning English they will also learn the language he

wishes to see extirpated from the country.

Although he acknowledges that the language cannot be "taught down"

in schools, yet, the idea of an advanced bilingual education scarcely seems

to have entered his head, as he speaks of schools not being called upon,

To impart in a foreign, or engraft upon the ancient, tongue a factitious

education conceived under another set of circumstances (in either of which

cases the task would be as hopeless as the end unprofitable), but to convey,

in a language which is already in process of becoming the mother-tongue of

the country, such instruction as may put the people on a level with that

position which is offered to them by the course of events.

Now, what the meaning of this mass of verbiage was, it is not easy to

discover, but it is squarely evident that in substance it amounted to a

repudiation of Welsh as a subject of instruction, and yet he acknowledges

that the best mode of teaching English was found at the Venalt Works School,

where the class was taught to translate, clause by clause, into Welsh; a

system which he compares to the Hamiltonian viva vocκ. How is it possible to carry this excellent method into

practice without interfering with the idea of employing the "old tongue

as a scaffolding," and leaving "no trace of it in the finished

building?" I venture to assert it is an impracticability, and is

repugnant to the laws of the human mind. How was it again, that when R. W.

Lingen's name figured as Secretary to the Education Department, and he

doubtless had the power of initiating many reforms, that this "best mode

of teaching" English was not recommended to all schools receiving the

Government grant in Welsh schools?

Amid the gross inefficiency of the schools in his district J. C. Simons sees

one gleam of light, but we fear it was a short-sighted vision; he says:

"There is one most striking and important peculiarity in

|

|

|

|

|

|

78 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. CHAP: III:]

them, which will be a subject of the utmost satisfaction to every friend to

Wales: it is the fact that there is but one day school out of the entire

number the three counties of Brecknock, Cardigan, and Radnor where the

Welsh language is taught. It seems scarcely to have occurred to him that it

is impossible to teach an English boy the French grammar without, to some

extent, teaching him English; likewise, that a Welsh boy taught English

thoroughly and in the most expeditious way, would have to be taught his

mother tongue as well."

It is this fear of children learning Welsh, and which exists at the present

time, that has been and continues to be one of the drawbacks of the intellectual

progress of Wales, and has degraded Welsh schools from being the arenas of

rational intellectual exercises of a higher stamp than those met with in

English school life; into scenes of mechanical, irrational drudgery.

Notwithstanding the fact which Symons says, was "a subject of the utmost

satisfaction to every friend to Wales," he has to admit that teaching

English by the methods then in vogue were a failure.

Any inference, therefore, that the children were extensively learning BngUsh,

drawn from the facts that the schools everywhere try to teach it, would be

utterly fallacious.

It is strange that with the many improvements of modern education there are

still schoolmasters, and possibly inspectors too, who cling to the old

injurious system of excluding Welsh entirely from the day schools except for

the purpose of simple explanation, so as to admit no books whatever printed

in that language.

For otherwise well educated people in responsible positions to ignore Welsh

as a medium of direct mental culture, and to regard it as an inconvenient

obstacle to progress, appears rather

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LANGUAGE. 79

a sheepish following of custom and tradition under the influence of the

Government regulations in force until recently, than the result of a well

matured and honest endeavour to fit the minds with which they are brought in

contact for the circumstances.

I say that schoolmasters cling to the old method, not simply because they

have been obliged to although there is no obligation to read the English Bible at the commencement of

schools but because they, or at least their managers, have generally

evinced so little disposition, to change a system condemned by such varied

and respectable authorities, as are adduced in the course of this work, for

one which would develop a better standard of intelligence in English,

although involving a better mastery of Welsh.

J. C. Symons says the "Welsh language is a vast drawback to Wales, and

that it is not easy to over-estimate its evil effects," and that there

is no Welsh literature worthy of the name, although he had never read a page

of what there was, while in a note he utters a half sneer at the

Cymreigyddion y Fenni then in existence, and at their making English speeches

once a year in defence of Welsh literature, saying, "Its proceedings are

perfectly innocuous.

If what he and his modern representatives say is true, how is it that in

Radnorshire and east Breconshire, where Welsh is extinct, we do not find the

people intellectually far in advance of Carnarvonshire? Let them give a

proper answer to that question before being so persistently dogmatic on an

unstable foundation.

Of course, my readers will bear in mind that some of the evidence must be

looked on with suspicion; we find for instance the magistrates' clerk at

Lampeter says, "the Welsh monthly magazines do more harm than

good," and he believes there is not a single Welsh weekly newspaper in

existence.

|

|

|

|

|

|

80 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [OHAP. III.

The following is from the pen of E. C. Hall, a barrister at Newcastle Emlyn:

The two languages are a great facility to perjury. The want of accuracy in

the knowledge of the language seems to remoye the feeling of degradation * *

The Welsh language is

peculiarly evasive which originates from its having been the language of

slavery!! (p. 34-5.)

Did it never occur to this man that if barristers, such as he, and the Judges

of Assizes, and Chairmen of Quarter Sessions, were not allowed to perform

their duties without a knowledge of Welsh, it should put a stop to some of

the perjury he speaks of; and if he is so shocked at perjury, why does he

bring in a shameful mis-statement about the Welsh language. Would he have

called leuan Gwynedd's language, which I shall refer to presently, evasive

had he been able to read it?

Colonel Powell, Lord-lieutenant for Cardiganshire, complains of people being

disposed to shew less respect to the old families of the county than they

used to be, and that the Welsh language is a great obstruction to the

improvement of the people.

A land agent at Aberystwyth who held courts leet for the Lord-Lieutenant,

echoes his master's words, and says that the language is an impediment to the

improvement of the people; but he adds that the people are very much attached

to it, although a preacher in the same county says they would not value a

school teaching Welsh.

Now, while Commissioner Symons dismissed the subject of Welsh literature as

scarcely worth discussion, and Lingen scarcely alludes to it all, Vaughan

Johnson took the trouble to prepare an abstract of Welsh literature, or

rather, I suppose, employed some one to do it for him, in which it appeared

that at that time there were current 405 works (Welsh) printed and read in

North Wales, of which 64 were books of poetry.

|

|

|

|

|

|

[chap. III. HER LANGUAGE. 81 46, prose

works on miscellaneous subjects. Although he ventured to remark about the

latter, that most of them, besides books on domestic medicine, and diseases

of cattle, were of a "frivolous character," he is candid enough to

say that he was unable to obtain an impartial statement of the character of

the periodicals, and accordingly printed in his appendix a translation and

brief abstracts of their contents.

A "communication" is given on the "Exclusive character of

Welsh literature," from which I extract the following:

The poverty and indifference of the Welsh people, and the difficulty of

withdrawing any of their attention from questions of theology and polemical

religion, forbid all hope of extending Welsh literature, without the hearty

and continued co-operation of the wealthier classes. No person would venture

to set up a periodical of a merely literary or scientific character, unless

he had the support of some religious party; and such a support cannot be

obtained to any extent, (p. 251).

How can the wealthier classes co-operate, if they too are shut out from a

knowledge of the medium whereby they might share their superior advantages

with their poorer neighbours.

Take away every field of activity but one, from a Welshman as such, and why

blame him or his language because he appears to be exclusive. Religion was

undoubtedly intended to leaven the whole life and not to be the foundation

for the battering rams of party animosities, or a vain love of disputation,

which perhaps after aU has been a form of intellectual restlessness finding

vent in an unusual way, but going unhappily under the name of religion, while

the paths of general knowledge are made unnecessary hard and rugged.

The Commissioner alludes to numerous periodicals pubUshed in Welsh by means

of which "all that goes on in England is known in Wales, being read by

the quarrymen and tradesmen, but not by the farmers, they read nothing. * *

It matters

|

|

|

|

|

|

82 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [CHAP. III.

not how plain and colloquial the style of a book, the farmers complain that

they cannot understand it."

A sixpenny or at most a shilling book of a relig^ious character is the only

safe publishing speculation in the Welsh language, and even this would be a

loss, if it were not "pushed" in religious circles. It is by no

means an uncommon thing for books to be advertised from the pulpit, in

dissenting places of worship, (p. 522.)

To some extent, though not nearly so much as formerly, this remark holds good

to day. There are populous sections of the country where Welsh theological

works occasionally sell well, considering the class of buyers. Yet if a

person were to write a general treatise in Welsh on a scientific subject, say

agriculture, the same readers would find a difficulty in understanding him,

and the sale would be small.

This is explained, not by lack of interest in those subjects, but because the

opportunities of the people have been too limited to acquire a sufficiently

extensive Welsh vocabulary (other than in the domain of Theology) to read

general literature with interest.

I was not long ago at Mountain Ash, among a mining population, where a

bookseller, with a Scotch name, assured me that he had sold one hundred

copies of the 2/6 edition of Principal Edwards' Eshoniad ar yr Hebreaid

(Commentary on the Hebrews). This is the more remarkable, as English is the

usual language of the children; but the probability is that some of those

very children will be added to the circle of Welsh readers, at least to that

of Theological ones. In this instance, the large sale is accounted for by the

Hebrews being at the time, a subject of examination among the Oalvlnistic

Methodists. The same bookseller also told me that he had sold several copies

of another religious work at 5/-.

NoWg so long as the language is scouted, frowned at, and thwarted in its

growth in the day school, and the people are

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, III.] HEK LANGUAGE. 83

denied secular instruction in it, would it be a matter of wonder that "

its resources in the other branches remain obsolete and meagre"? Would

it be a matter of wonder that books on general subjects do not find a ready

sale? It is however not correct to affirm that the resources of the language

are meagre, and the wonder is that they have been developed so much as is the

case.

Symons and Lingen, both of them comment on the extraordinarily unintelligent

way in which Education was carried on, yet neither of them suggest such an

improvement as bilingual books; although David Charles, Principal of Trevecca

College, very sensibly said in a communication to J. C. S. " I would

also recommend that the Welsh receive their knowledge of the English language

through the medium of their own, at first by means of Welsh books. The want

of this mode of instruction has been a great drawback which I have often

desired to get removed."

Not merely did David Charles make this objection, but another leading

dissenter, Lewis Edwards, of Bala, held the same view, as shewn in the

following translated extract from the Traethodydd of 1850. (See Traethodau

Llenyddol, p. 120):

Prom the bottom of our hearts we give our consent to every word that is said

by Sir Thomas Phillips about the necessity of teaching Welsh children in the

Welsh language. * * The truth is, that the easiest way for them to learn

English is to give them a taste /or and knowledge in the Welsh language.

The North Wales Commissioner displayed more practical ability than his

colleagues, in severely commenting on the exclusive use of English books, and

the English language, and says that the promoters of schools appear

unconscious of the difficulty (as some are to-day), and the teachers of the

possibUity of its removal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

84 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]. [CHAP. III.

After saying that he had found no class of schools in which an attempt had

been made to remove the children's difl&culties of first learning

English, he makes the following general remarks:

Every book in the school is written in English; every word he speaka is to be

spoken in English; every subject of instruction- must be studied in English;

and every addition to his stock of knowledge in grammar, geography, history,

or arithmetic, must be communicated in English words; yet he is furnished

with no single help for acquiring a knowledge of English. As yet no class of

schools has been provided with dictionaries or grammars in Welsh and English.

The promoters of schools appear unconscious of the difficulty, and the

teachers of the possibiUty of its removal.

Speaking of the Grammar School at "St." Asaph,

Those who learn Latin are provided with grammars, dictionaries, and

vocabularies; but here as elsewhere no hand-books have been provided for

learning EngUsh, although English is to many of the pupils as unintelligible

as any dead language.

Nearly fifty years have passed away, Welsh education has been, very much in

the hands of the English Government, clerical officials, and other persons,

who have sought a share in its management, and yet this monstrous anomaly so

disgraceful to the civilization of the nineteenth century remains, and it is

even defended by a certain class of teachers bred under the influence of long

standing customs and EngUsh laws.

H. V, J. introduced into his report a mention of the "Welsh note,"

a stigma of disgrace transferred to the last boy heard speaking Welsh. Among

other injurious effects this custom has been found to lead children to visit

stealthily the houses of their schoolfellows, for the purpose of detecting

thbse who speak Welsh to their parents, and transferring to them the

punishment due to themselves."

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. III.] HER LAIWJUAGE. 85

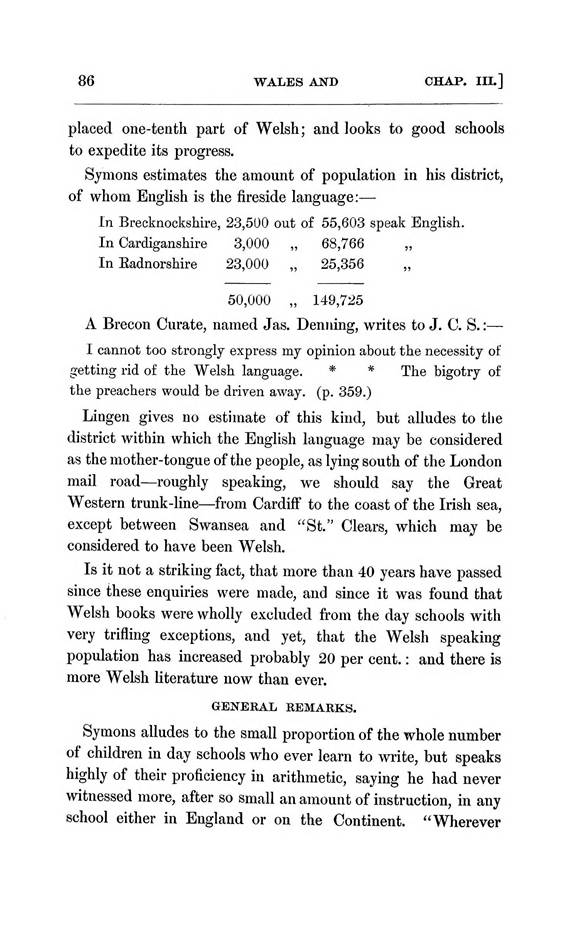

The same Commissioner speaks of the impediment to efficient teaching oflfered

by the prejudices of Welsh parents against the employment of their own

language, even as a medium of explanation: " In the day schools we want

our children to be taught English only; what good can be gained by teaching

us Welsh? We know Welsh already." There are too many School Boards in

1891, where this kind of ignorance appears to prevail concomitant recollect,

with a genuine attachment to Wales."

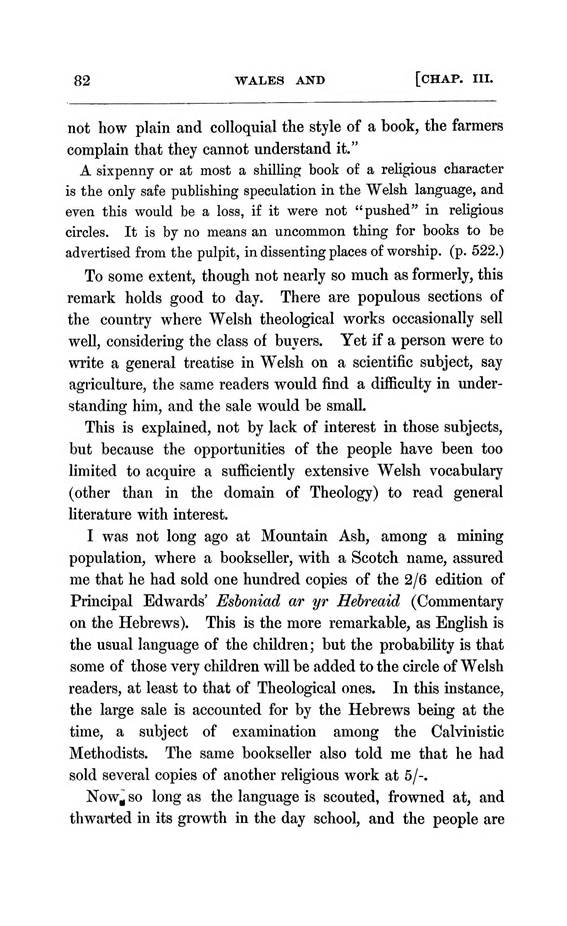

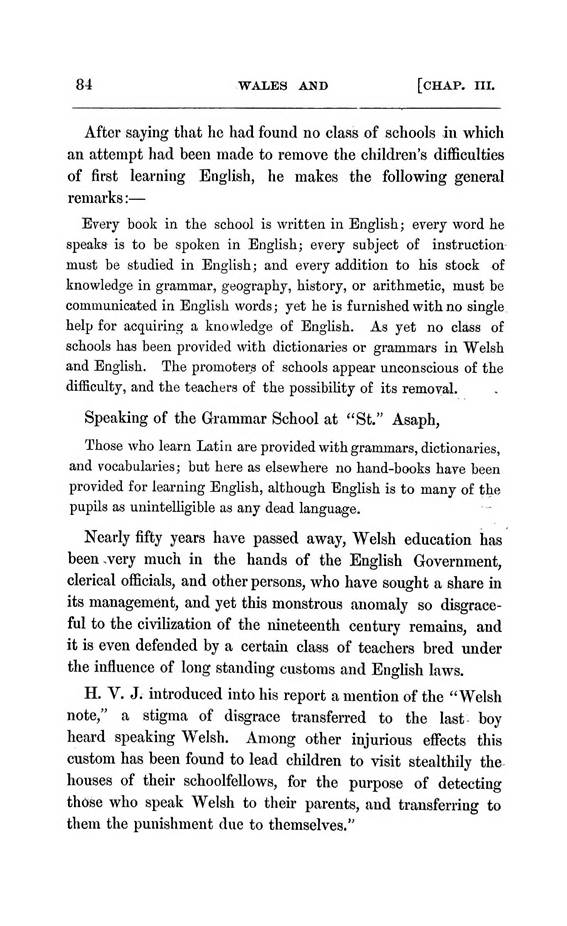

The following table may be of some interest:-^

CLASSIFICATION OT DAT SCHOOLS ACOOEDING TO LANGUAGE IN

1846-7.

Language of Instruction.

Welsh only

English only

Welsh & English books

English books only* ] but Welsh spoken I 118 63 48 25 8 -- 7

in explanation J

Grammar of English.. 74 127 67 57 35 12 37 of Welsh . . _ _ _ _ of

both . . 2 2 1 ^

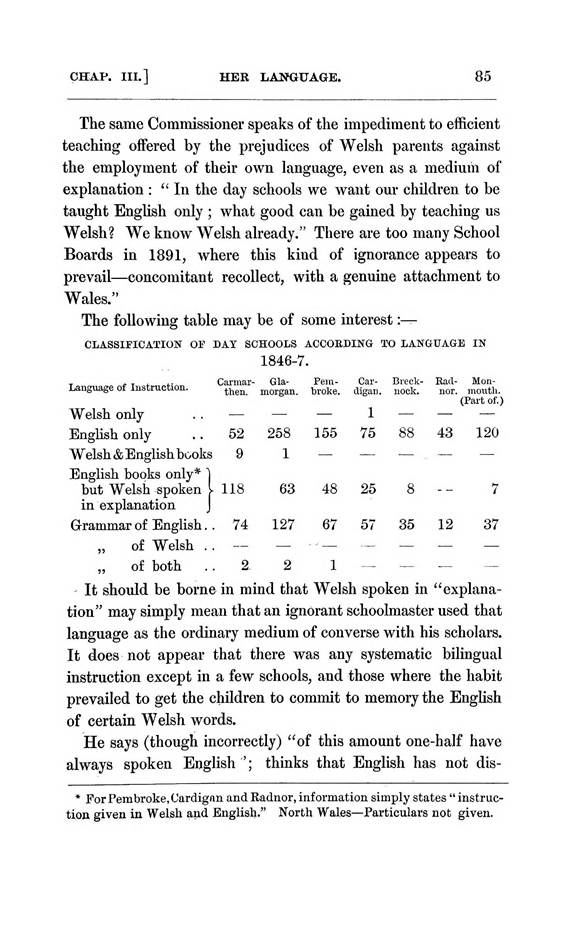

It should be borne in mind that Welsh spoken in "explanation" may