.....

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAPTER IV.

INTERMEDIATE EDUCATION — LLANDOVERY GRAMMAR SCHOOL AND THE PROVISIONS OF ITS

FOUNDER FOR TEACHING WELSH — THE INTERMEDIATE EDUCATION COMMISSION OF 1880 —

ESTABLISHMENT OF UNIVERSITY COLLEGES — THE LONDON CYMMRODORION AND THEIR SYSTEMATIC

ENQUIRY FROM WELSH ELEMENTARY TEACHERS — REPLIES PRO AND CORE — THE ABERDARE

EISTEDDFOD OF 1885, AND THE FORMATION OF A SOCIETY FOR UTILIZING THE WELSH

LANGUAGE IN EDUCATION — OPPOSITION TO THE PROPOSAL — D. ISAAC DAVIES, HIS

LETTERS TO THE "WESTERN MAIL" AND "BANER AC AMSERAU CYMRU."

rpHE preceding Chapters having been principally devoted to -^ an elucidation

of the state of Elementary Education in Wales from forty to fifty years ago,

it will be necessary in the present one, to revert to the same period,

briefly noticing some facts affecting intermediate and higher education,

before following out at length the controversy started a few years ago by a

Welsh Society in London, and afterwards more or less in the cou]itry at

large, as to the desirability of a radical alteration in the existing methods

of dealing with Welsh schools principally with regard to elementary ones, but

also to some extent, including the whole educational system.

In Wales the ingenious educationalists of two or three generations past,

contrived a remarkable expedient for the employment, if not amusement of the

boys in middle class schools, which consisted in hounding their language down

by means of the Welsh note, which was a stick of wood passed on from one boy

to the next, who was heard speaking Welsh. At the end of a certain period,

the last possessor of the "note" or "stick" was punished.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] WALES AND HER LAJNGUAGE. 107

The custom was not confined to middle class schools, as appears by the

following in H. V. Johnson's report of Llandymog, Denbighshire: —

My attention was attracted to a piece o£ wood, suspended by a string round a

boy's neck, and on the stick were the words, "Welsh stick." This, I

was told, was a stigma for speaking Welsh. But, in fact, his only alternative

was to speak Welsh or to say nothing. He did not understand English, and

there is no systematic exercise in interpretation, (p. 452.)

We ask what kind of metal were the masters of those times made of, when we

learn that "among other injurious effects, this custom has been found to

lead children to visit stealthily the houses of their schoolfellows for the

purpose of detecting those who speak Welsh to their parents, and transferring

to them the punishment due to themselves? See also

Appendix D.

I have had occasion to allude to the attitude, and think I am justified in

calling it the prevailing attitude at that time, of representatives of the

Established Church towards the Welsh language. I shall not, however, be

understood to imply that this was universal. The year 1847, saw the

foundation of a scheme which, though under the care of the Established Church

had for one of its express purposes the colloquial and literary cultivation

of the Welsh language, and is at the present day (apart from questions of

religion) one of the best, if not the best higher class school in Wales.

The following extract from a summary of the provisions of the Deed of the founder,

viz., Thos. Phillips, a London Welshman, who bestowed nearly £5,000 for the

purpose, gives some idea of his views: —

The scholars will be instructed in Welsh reading, grammar, and composition;

in English, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, arithmetic,

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

108 WALES AND [CHAP. IV.

_^ «a

algebra, and mathematics; in sacred, English and general history, and

geography; and in such other branches of education as the trustees, with the

sanction of the visitor, shall appoint. The Welsh language shall be taught

exclusively during one hour every school day, and be then the sole medium of

communication in the school; and shall be used at all other convenient

periods as the language of the school, so as to familiarize the scholars with

its use as a colloquial language. The master shall give lectures in that

language upon subjects of a philological, scientific, and general character,

so as to supply the scholars with examples of its use as a literary language,

and the medium of instruction on grave and important subjects. The primary

intent and object of the founder (which is instruction and education in the

Welsh language) shaU be faithfully observed.

So far we say so good, but the crucial test of a middle class school in

England or Wales now^-a-days, is generally looked for in its ability to

prepare for the preliminary examinations of English Universities, few

schools, if any, unless carried on under exceptional circumstances, think

they can afford to work to entirely independent standards of their own. This

has directly or indirectly affected the course of instruction at Llandovery,

so that the intentions of the founder have not probably been carried out to

the fullest extent, although they have been so far as to materially increase

the usefulness of the institution.

I have mentioned that Llandovery school was (and is still) under the care of

the Established Church, so is that called " Christ's College,"

Brecon, with a good organization and an annual endowment of £1,200; other

Welsh endowments were mostly either denominational or inadequate, and for a

number of years it was felt that the needs of the country demanded

considerable improvement in the facilities for Litermediate Education,

especially in such as Nonconformists would be likely to freely avail themselves

of.

In 1880, in compliance with representations made to it, the

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.J HER LANGUAGE. 109

Government appointed a Committee, to enquire into the condition of

Intermediate and Higher Education in Wales, consisting of the following

persons, —

Lord Aberdare

Viscount Emlyn

H. G. Robinson (Prebendary of the Established Church).

Henry Richard, M.P.

Professor Rhys

Lewis Morris.

The main scope of the enquiry of this representative Committee was confined

to the question of the utilization of endowments for middle class schools in

Wales, and the best method of supporting such in the future.

As might be expected from its constitution, the Welsh Language received

considerably more respect from the Commission than from that of 1847. Its

power and vitality were acknowledged, but the Repprt offered no suggestions

as to any improved method of coping with the difficulties, created by the

existence of a household language, side by side with a system of education

which ignored its existence.

The immediate result of their labours was the establishment of University

Colleges for North and South Wales, and the giving of an annual subsidy to

the one at Aberystwyth, which, after considerable demur, the Government

wisely consented to retain.

A very important recommendation was made by them, viz.: — the creation of

what amounted to a Welsh University, with the representatives of the leading

colleges on its Governing Board, which was not, however, carried into effect;

but, perhaps we may, in some measure, trace the passing of the Intermediate

Educational Act for Wajes, with the powers it conferred on County Coimcils

for the establishment of middle class schools, to the labours of this

Committee. Nor

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

110 WALES AND CIIAP. IV. J

was the work of the Commission iu any way directly related to that movement,

the rise, and progress of which I am about to trace; but inasmuch as the

establishment of these University Colleges has given some educated Welshmen a

vantage ground to co-operate vdth it, and as no single part of Welsh

education can be looked at without reference to the whole, it may not have

been out of place to give a few brief hints at its work.

At present this movement is confined within comparatively small limits, and

although it has gained some victories, there is still a possibility of its

retiring from the field without permanently occupying the ground gained. It

has, however, within itself the germ of an educational revolution for Wales,

which may yet wonderfully modify the future history of that country. Be that

as it may, there has been so much of interest bearing on the relation of the language

to the social and intellectual life of the people, evolved by enquiries and

discussions set up in connection with its operations, that a wise historian

cannot refuse to notice them, and in a work of this kind, it is deemed

necessary to give details somewhat more at length than may perhaps please

some persons to whom the power exercised by the language in the past and in

the present, is an unsolved and unsolvable enigma.

In 1884 the Cymmrodorion Society, having its head quarters in London, appointed

a committee to enquire into certain points relating to Elementary Education

in Wales, which were in brief the alleged defects of teaching English, and

the proposal that it should be taught through the medium of Welsh. Questions

bearing on these points were sent round to about thirty leading

educationalists in Wales, including Wm. Williams (the senior Inspector of

Elementary Schools). It was found on receipt of replies that only one

correspondent positively expressed depreciation of Welsh as a subject of

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. Ill

education, while the Principal of the Normal College, Bangor, was one who

strongly advocated its introduction.

The next step of the Committee was to address an enquiry to the head-masters

and mistresses of primary schools in Wales, as follows: —

Do you consider that advantage would result from the introduction of the

Welsh language as a specific subject into the course of Elementary Education

in Wales?

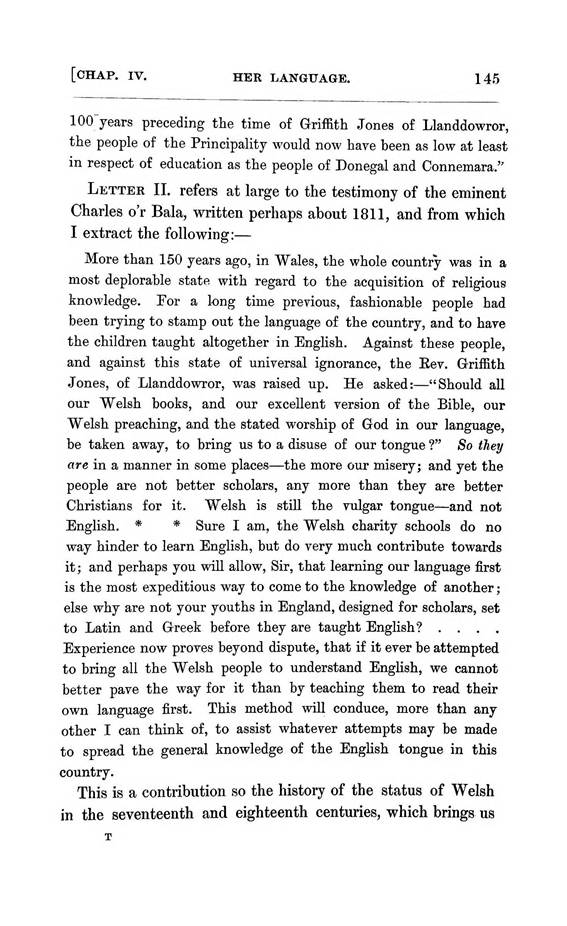

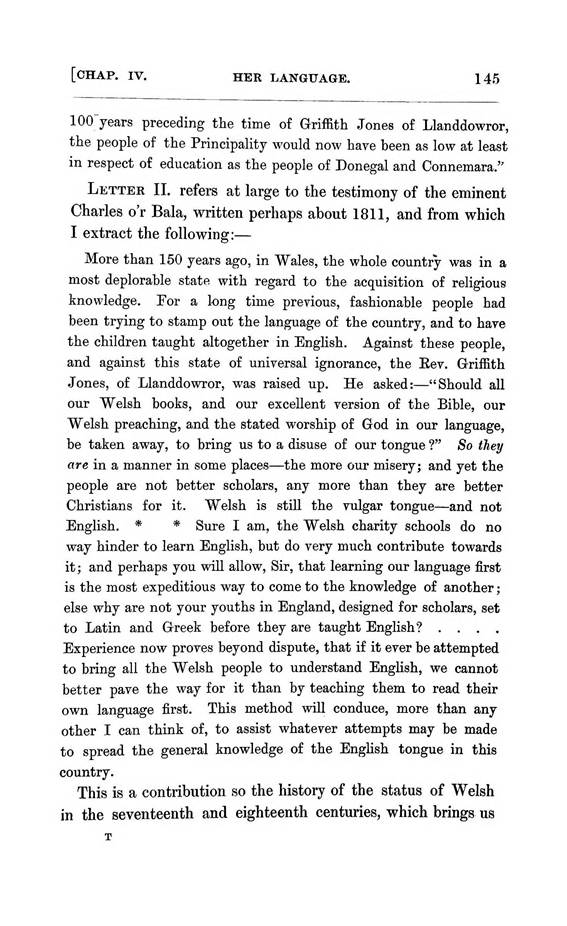

In the Spring of 1885, 628 answers were received, of which 339 were

affirmative, 257 negative, 32 neutrals. For a tabulated statement of these

replies, arranged according to counties. See Appendix E. By this it will be

seen that Flint and Pembroke were the only counties that shewed negative

majorities. Somewhat singularly, the county of Monmouth, where Welsh is not

much spoken as a family language, shewed a majority in the affirmative, while

the busy, industrial county of Glamorgan, shewed no less than a majority of

57 per cent, of affirmative over negative replies.

The replies of these teachers form in the mind of the writer, one of the most

interesting contributions to the literature of Wales, that have appeared

during the present century. To reproduce the whole would take up too much

space, I therefore propose to give selected extracts from them, or summaries

ranged under their respective Coimties.

The original printed report of the Cymmrodorion and the appendix, giving the

replies in full, are perhaps not easily accessible to most of my readers, and

as the negatives touch on nearly everything that can be said now against any

similar proposal, it is well they should be heard, although for the most part

their arguments were decidedly the weakest, except where any of them felt

that Welsh as a class-subject would meet the case better than as a specific.

It must be borne in mind that these replies were written

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

112 WALES AND [CHAP. IV.

before the subject had been canvassed by public discussion, and that early

prejudices doubtless biased some of the writers, from whose school and

collegiate courses Welsh had been excluded.

They are however valuable as the independent witness of a number of

intelligent men with trained minds in different parts of the country, and

surrounded by very different conditions,

I have not quoted the reference numbers given in the original, except

occasionally for the sake of clearness, but the reader will bear in mind that

each separate paragraph is written by a different teacher, and that it does

not in every case comprise the whole of the answer, ANGLESEY.

Negative. — I don't think that Welsh parents would welcome the introduction

of "Welsh" as a subject into our schools. They want us to prepare

their children to fight the "battle of life." But I am of opinion

that the G-overnment ought to raake some allowance for the difficulties we

hare to encounter in teaching English to our pupils.

The greatest opposition would be offered in this district to Welsh being

introduced, as all parents with whom I am acquainted are most anxious that it

should be altogether excluded from school work. My opinion is that

"well" is best let alone. So my answer is "No."

No. For: (1) Parents would not stand it. (2) Welsh is amply cared for by our

Sunday schools and literary meetings. (3) I cannot see the utihty of the

proposal. (4) Our schools are Welshy enough as it is. (5) After eight years'

experience I find the best plan is to use the Welsh language as sparingly as

possible. Of course we all love the old tongue, but school life is not a

matter of sentiment, but a serious preparation for the battle of life. (6) I

am certain if you succeed few teachers would care to teach it, as it would

seriously interfere with other more important work.

|

|

|

|

|

|

[OHAP. IV. HER LANGUAGE. 113

No. Reasons: (1) Sufficient latitude is already given by the Educational Code

for the employment of Welsh as a medium of teaching English. (2) Teachers having

no knowledge of Welsh, and those who entirely discard it in teaching Welsh

pupils, are highly successful as such in Wales. (3) If Welsh were included as

a specific subject in the Educational Code, I, in anticipation, assert that

no more than one out of ten teachers would adopt it. (4) My knowledge of

people of both mining and agricultural districts enables me to say positively

that the teaching of Welsh in our schools would be much objected to. (5) The

introduction of Welsh into the curriculum of the schools would greatly hinder

the teacher in endeavouring to encourage English conversation among his

scholars.

Afeiematite — ^The introduction of Welsh as a "specific subject"

wUl be of great benefit to schools where the children are entirely Welsh.

Many children now leave school when they can neither write English or Welsh

correctly.

Most of the young men, after passing the fourth standard in a day school, as

well as attending Sunday schools, are unable to compose either Welsh or

English. Whereas if they were all grounded in their "mothers'

tongue" in elementary schools it would be an inducement for them to

compete at Uterary meetings, Eisteddfodau, &c., and at the same time it

would assist them to understand the English language.

(1) It would afford a highly interesting (because thoroughly understood)

mental training, and English would be more efficiently taught than at

present, on the natural principle of proceeding from the known to the

unknown. (2) A child would comprehend the grammatical structure of his native

tongue, and compose in it with ease; thereby acquiring a power and model to

deal with English and other languages. The majority of children leave school

with very imperfect notions of English composition, and none of Welsh, as far

as school teaching helps them; and parents justly complain that their

children cannot write correctly " either an English or a Welsh

letter." (4) Such being the universal complaint, it follows

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

114 WALES AND [OHAP, IV,

that the present mode of teaching English has lamentably failed (except to a

few talented youths in each school), and some course akin to the suggested

syllabus must be adopted before any better results can be obtained from the

great majority.

It would be a great boon to the children in order to aid them to understand

the English language. It would create in their minds when leaving school a

thorough love for higher education in science aftd literature.

The study of such a beautiful, poeticai,, and bxpebssite LANGUAGE as the

Welsh would carry its own intrinsic value in the possession of the full

command of such a language to. clothe his thoughts.

Though an Enghshman, I have been very much struck with the slight knowledge

of "Welsh grammar as evinced by the working class with whom I have been

brought in contact.

By placing the Welsh language among the specific subjects, I do not think

that any English teacher would find that he was handicapped in the matter. I

thoroughly endorse the opinion of Mr. Edward Eoberts, B.A., H. M.'s Inspector

of Schools. OAENAEVONSHIEE.

Negative — No; because (a) Welsh children's knowledge of Welsh being for the

most part only of colloquial Welsh, they would have to unlearn a great deal

before any progress could be made, (b) The parents of English children in Welsh

schools would very probably object to their children learning Welsh.

Our literary associations and Sunday schools are ample means of supplying the

required knowledge of the Welsh language.

No, a thousand times no. A discreet use of Welsh in the lower standards is

commendable, and may be for some time yet indispensable. * * Every Welsh

teacher I have yet spoken with emphatically condemns the idea. Indeed, most

of us have not even acquired a knowledge of the rudiments of Welsh grammar,

so utterly purposeless is its acquisition to successful teaching.

No. Perhaps it would be an advantage to teach it to the pupil-teachers, as

this would in time largely increase the number of Welsh

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 115

writers. The Go7ernment might be asked to set papers in the "Welsh

language at the scholarship and certificate examinations. I think I am not

wrong in stating that at present there are but very few of the Welsh teachers

who can write Welsh.

Afeiematite — Yes, provided it should be taught as a class subject, and not

as a specific subject.

Welsh-English translation being under existing conditions copiously

practised, I do not see that any material extra labour would result from the

adoption of Welsh as a " specific," nor that it would necessitate

the dropping of the ordinary class subjects. Though there is a cry for

English, yet parents are quite as anxious for their children to be able to

write respectable Welsh letters. I say yes, on financial and educational

grounds.

I maintain that nothing but a parrot-Hke knowledge of English can possibly be

imparted to scholars in Welsh-spoken districts, as far as Standard III.

inclusive, without freely using the Welsh language. This being done in the

majority of elementary schools in Wales, the teaching of Welsh as a specific

subject would require so Utile extra wjrk that there would be no need to drop

any of the ordinary, in order to introduce it. Having been engaged in schools

in Welsh-spoken district over fourteen years, I hope you will excuse me for

giving expression to the above statements.

It would be a good foundation for the learning of English. I have been

repeatedly asked by parents to teach Welsh composition (letter-writing) to

their children; of course, without neglecting English in any way.

Tes, I believe that the introduction of the Welsh language into the

curriculum of elementary syhools, wiU greatly facilitate the teaching of

English in purely Welsh schools.

I do really consider that the introduction of the Welsh language as a

"specific subject" would enhance even the speedy acquisition of

English, and a better grounding of the Welsh language than we have hitherto

possessed, providing that a Welsh grammatical primer suitable to the capacity

of the children would be supplied, containing sentences that would render a

mutual aid to acquire a

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

116 WALES AND [OHAP. IV.

sound elementary knowledge of both languages. Whatever is said of Sunday

school teaching, my experience assures me that many a Sunday school scholar

does not know the difference between i'w and yw, and mae and mai, and in this

respect it is a complete failure, and the only remedy would be acquired by

the introduction of Welsh as a specific subject.

Being a most ancient and original langu9,ge, its knowledge could not fail to

be an inteoduotion to a classical education. In Welsh-speaking districts I

consider the vernacular the best medium of teaching EngUsh and of improving

the general intelligence.

Yes. It would be far more serviceable than Euclid, &c., to the lads of

the Welsh-speaking districts of Carnarvonshire, &c.

Few English families reside here, but I find that the English children in a

very short time are able to talk Welsh, and will insist upon speaking it

every chance they obtain.

Yes. It is an act of justice to an ancient people and their language. It will

give the rising generation an inteUiggnt and grammatical, as well as a

practical knowledge of their native tongue, and enable them to correspond

with facility in Welsh, whereas at present many Welsh people correspond with

each other in English.

Before the schools of Wales will be on an equal footing with those of

England, your plan should be adopted.

Netjteal — It would be of great advantage to these, if they were able to

write and compose in their native language. But they have had no practice and

no opportunities to learn these useful acquirements.

DENBI&HSHIRE.

Negative — No, I do not. I confess that EngHsh could be better and more

thoroughly taught through that medium, but it would very much retard the

progress of the scholar. The greatest objection I see to it, is the fact that

few schoolmasters, although Welsh, can write or understand Welsh correctly.

Also, it would take as much trouble to get the children to understand the

proper Welsh language as it would to do the EngUsh. I say proper.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LAITGUAGE. 117

because children do not speak it properly — and differently in different

districts.

Decidedly no. Because there is too much division in the British empire now,

and the giving legal sanction to another language will only increase the

division. Because there are too many subjects taught already.

No. But I think it would be good to give a small piece in English language as

home lesson, to be translated into "Welsh, such as a letter from a

friend. I have been doing so, and found it to do good.

I would most decidedly say "Yes" if it was introduced as a class

subject.

Afeiematite — ^Tes. I believe the knowledge of even two languages (Welsh and

English) to be stimulative to the mind, by exciting comparison and enquiry.

Welsh, being a root language, gives a good insight into the construction of

languages.

In my humble opinion, which is based upon a residence of more than

twenty-five years in North Wales, all tJie schools would do well to teach the

Welsh language as a " specific subject," as I fully beheve that

quite four-fifths of the children understand and speak the native tongue. I

would except the eastern portion of Montgomeryshire, and perhaps two or three

schools at Ehyl and Llandudno. A boy who is conversant with both languages

has, in more than one way, an advantage over a boy who simply knows English.

* * * I deem it a great advantage to know a bbatttiful, PHONETIC, HXPEBSSiTE

language, such as the Welsh is.

FLINT8HIEE. Nhgatitb — Eather than introduce the Welsh language as a specific

subject, it would be more fair to the teachers in the Principality for the

Committee of Council on Education to acknowledge the disadvantage under which

they work, especially in rural districts, and draw up a simpler and special

Code for the Welsh Schools, in order to put them on a more common-sense level

with the EngUsh schools, where the children know nothing but their

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

118 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] CHAP.

IV.]

mother tongue, English, from their birth. What would the English teachers do

if they had to teach every subject in the French language to children who had

been taught English from their birth, and who heard nothing but EngHsh at

their homes and while at play; and those children again to be examined in the

same subjects as French children of the same age? The use of both languages

must be made by the Welsh teachers before English can be taught in the

schools of the Principality.

No. At least nine out of every ten of the teachers would require special

training.

AFFIRMATIVE — I do. I have had an opportunity of (more than once) lecturing

on Welsh grammar before "Young Men's Literary Associations," and in

each case a decided craving for such a move as you recommend was manifested.

As an old pupil of the Rev. Jenkin Davies, Rector of Bottwnog, Caernarvonshire,

I consider his method of teaching English one of the best for beginners in a

Welsh country school — e.g.: The

Verb "to be" Indic. Pres. Singular. — I am = yr wyf fi; Thou art = yr

wyt ti; He is = Y mae ef. Plural. — We are = yr ydym ni; You are = yr ydych

chwi; They are = y maent hwy. The introduction of the Welsh language as a

specific subject into the course of elementary education in Wales would, I

firmly believe, be of great advantage to both teacher and scholar. The most

successful teachers use it freely.

MERIONETHSHIRE.

NEGATIVE — And what a disadvantage a Welsh teacher and the children under his

charge would be labouring under in comparison with an English-speaking

teacher, even in Wales, and much more so in comparison with an

English-speaking teacher in a district exclusively English, who one and all

are expected to produce the same or similar results, independent of

circumstances over which they often have no control, or be involved

helplessly in professional ruin. See reply to No. 7 B., the said H. M. Senior

Inspector. "Edrych yn y drych hwn

dro, gyr galon graig i wylo."

No. The introduction of any Welsh into this school would be

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP, rv.] HER LANQTJAGB. 119

very unfayourably met by the parents; even now they will blame the teacher

for explaining difficult passages in English by means of the "Welsh

language.

Reducing the number of readers in Welsh schools, so as to give teachers more

time to cultivate intelligence by means of translation, as prescribed by the

Code, would secure the same result.

Affirmatite — I consider that great advantage would accrue. I may state that

the Welsh is now universally made use of in the lowest standards; and ideas,

when expounded in Welsh, seem to adhere longer to pupils' minds, especially

in purely Welsh speaking schools. By the adoption of the proposed scheme,

both the Welsh and English languages would be more thoroughly known in the

Principality.

There is no doubt but that a very great advantage would result from it,

because the Welsh language is not properly taught at our Sunday schools,

&c., as asserted by some; but really it puzzles me to know how it can be

introduced into the course of elementary education in Wales with the present

requirements of the Code. The best teachers already groan under the drudgery.

Although my Welsh is very imperfect, I vote strongly for its introduction

into Welsh schools, not as a medium for teaching English, but as a sbpabatb

subject paid for by the Education Department as a class subject in the same

ratio as our other class subjects; and I would furthermore suggest that in

Welsh schools all teachers may have the option of teaching grammar (English)

and Welsh, instead of grammar and geography.

Wbttteal — After advocating beginning Welsh in the early Standards, "

There wUl, I know, be too much timidity to ask for such a radical change in

the Code, until Welshmen who would be listened to by the Department discover

the dreariness and the unnaturahiess of the present methods of teaching in

our infants' and junior classes. The handful of Gaelic-speaking population in

Scotland seem to have more official cognisance in this respect than our

Welsh-speaking population of one million, with a living literature to

boot."

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

120 WALES AND [OHAP, IV.

M0NTG0MEET8HIEB.

Negative — [Answers 11, 12 and 13 allude to the preyalence of English in

their districts.]

I think no advantage would result from its introduction as a "specific

subject." (1) It would tend to isolate Wales from becoming assimilated

with England in every sense of the word. (2) No adequate return would be

obtained in after-life. (3) It would unnecessarily burden the already

hard-pressed teacher in rural districts. (4) It would tend to exclude English

teachers from taking charge of schools in Wales.

Affiemativb — Tes, especially where the Welsh language is likely to be

forgotten.

I have only been a master in Wales for a few weeks * * as far as I can teU I

think it would be greatly advisable.

As long as the object of the Education Act is to teach English, the least of

Welsh used in schools the better, untU the children have learnt to thinh in

English. When that point is reached, as in upper standards (sometimes), Welsh

may then be taken without being a hindrance to their learning English — the

original object.

I do: (1) The study of the Welsh language is as much a means of MENTAL

DISCIPLINE and development as the study of the Latin, the French, or any

other subject at present mentioned in Schedule IV. of the new Code. (2) If a

child speaks the Welsh language, and is likely to use it during its lifetime,

a grammatical and systematic knowledge of it would render it of much greater

value to him or her than would be the mere power to speak it.

As a teacher of public elementary schools for upwards of thirty-four years, I

would most strongly advocate that teaching Welsh should be made compulsory in

all schools located in Welsh-speaking districts. There is not a better mental

culture, or one so well calculated to enliven and bring out the mental

energies of Welsh children, than to combine the vernacular with English.

CAEDIGAN.

Negative— [Along with other references to parents' objections.]

The chief request of all the parents that call upon me is to

|

|

|

|

|

|

chap; IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 121

make their children learn plenty of English. * * I have had experience in two

schools in different parts of Cardiganshire, and the chief and great desire

of the people is for the spread of English in those parts.

The introduction of Welsh in any form would seriously retard progress in

EngUsh.

Apmbmatite — ^Yes. Beason: In so much as I love Wales, and in particular the

Welsh language, I have always felt grateful towards St. David's College,

Lampeter, where the Welsh language is studied, and am glad of this present

opportunity of voting for the future existence of my mother's tongue.

Yes, as a "specific subject" if examined by Welsh inspectors. This

would bring Welsh children to have some regard and admiration for their own

language.

Yes, for it seems ridiculous that the present generation of children should

be able to express themselves better, on paper, in the English than in their

mother tongue. Welsh, as a 'written language, is falling fast into disuse in

Wales.

I am at a loss to see any objection, on the part of teachers, to its being

introduced as such. The correct rendering of Welsh in viriting is most

imperfectly known in these parts. The Sunday schools do nothing more than

teach the mechanical part of reading Welsh, leaving grammar, &c.,

entirely out of the question.

Yes. (1) I think the children would learn Enghsh better by such means than by

the present slipshod way of teaching, or rather not teaching it. (2) It would

be an invaluable exercise for the mind — i.e., the comparing the two

languages would be. (3) It would tend to keep alive the Welsh national

spirit, and although an Englishman myself 1 think this an hoxoubable and good

motive. (4) I think there is no doubt that Welsh literature would gain

immensely by such an introduction.

I do not hesitate for a moment to say "yes." But I am afraid

that the want of a proper staff in the majority of Welsh schools

to conduct the teaching of it as a specific subject will be a severe

check to the advantages thus to be derived. I should be incHned

Q

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

122 WALES AND [CHAP. IV.

to place it among the class subjects, or at least to include it in the

present class subject English.

EADNOE.

Negatitb — [Eeason assigned by two writers — Welsh unnecessary.]

AnrFiEMATiTE — "Welsh parents hare been, and still are, more or less

anxious that their children should learn the English language, but the

feeling in my opinion is not so strong now as it appeared to have been ten

years ago, when the almost convincing and loud cry was raised that their old

and dear language would in a couple of years die out never to revive again.

The inhabitants of the PrincipaUty at the present time, however, and after ten

or fifteen years' experience of such hue and cry, are not the least terrified

about the extinction of their language; in fact, the Welsh as a nation begin

to feel jealous of their language; they think it worthy of attention, and

indeed heed is paid to it now more than ever, and in a much higher sphere

than hitherto. * * To learn, even a little, of the Welsh grammar, and to

write Welsh correctly, would be of advantage to Welsh boys and girls in after

years. I was asked last Christmas twelve-month to adjudicate some poetry at a

competitive meeting written in English and Welsh. The Welsh idea was superior

to the English, but the spelling was wretched.

BEECKNOCZ. Afeiemativh — I believe the more intelligent farmers here would

like very much that their children should be taught to write Welsh correctly,

in addition to being able to read it, which they are now taught to do in our

Sunday schools.

PEMBEOKE.

Nesative — [No Welsh spoken — Parents' objections — Majority of teachers

English.]

Again, the parents of children would soon repudiate such a step; the

unanimous feeling is to see their children progress in Enghsh, for "they

can get as much Welsh as they want at home," and any shortcomings of the

same would soon be noised abroad.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 123

AiTiEJSiATiTB — ^Virtually I should say there would be an advantage to the

children themselves, but many "Welsh localities would discountenance

such teaching, owing to the notion that sufficient knowledge of Welsh is

being got at home, and that the school course should consist in the teaching

of the language of practical business, &c.

I am of opinion that children would be greatly deUghted and interested in

learning a subject so familiar to them, and it would be a great step towards

bringing out their intelligence.

I feel compelled to answer " Decidedly yes," as I am unable to

teach my Standard II. children nouns and verbs in the English language, and

am obliged to resort to corresponding "Welsh nouns and verbs. This is

more difficult as I am English. CAEMAETHENSHIEE.

Negative — Parents are very anxious that their children should learn English

well, and those who have learned English grammatically have Uttle difficulty

in writing a letter in "Welsh fairly. They learn to read in the Sunday

schools in "Welsh, and nearly every family takes a weekly "Welsh

paper in this locaUty. "Welsh is spoken by 99 per cent.

Children and teachers overpressed. ''' * The popitlab DELirsioN [that of

parents thinking the Sabbath school (so called) sufficient for picking up

Welsh] must first be removed before any general teaching of Welsh be

obtained.

Children, however, on leaving school take up Welsh or English papers, no

matter which. But although the rising generation is well able to speak

English in their business affairs (which I cannot say their parents can do),

the language at home is essentially as "Welsh" as ever.

This district is entirely Welsh, but, strange to say, no one writes or

carries on correspondence in Welsh; all is done in English.

No. I speak from an experience of eighteen years as a master of schools in

strictly Welsh-speaking districts. The teaching of Welsh as a specific

subject will not be advantageous because it

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

124 WALES Al^D . [chap. IV.

will iacrease and not lighten the existing pressure. * * As a practical

teacher, and as a warm advocate of the retention of the Welsh language, I

should suggest as practicable and advantageous the substitution of Welsh

translations for the present burdensome and often useless learning by a rote

of a number of lines of poetry with meanings and allusions.

Apeiemativb — Tes; but I believe that parents would be very much opposed to

it.

In my opinion considerable advantage would result, but the parents would

object.

It might prove advantageous, especially when such encouragemant as that

offered by Dr. .Tohn Williams, of 11, Queen Anne Street, London, is given in

the form of an Exhibition of the annual value of £27, tenable for four years,

at The College, Llandovery, or Christ College, Brecon, to lads under fourteen

years of age from elementary schools in five surrounding parishes, one of the

subjects for examination being: " Welsh — Beading and translation from

Welsh to English,"

It would also be the mjans o£ cultivating the intelligence of the pupils. It

is a great pity, if not shame, that we (Welshmen) do not study our language

properly, so as to be able to enjoy the writings o£ our excellent authors, in

poetry and prose.

[Particularly thoughtful answer]. In my opinion it would be a decided

advantage, particularly so in country districts, where few attractions are

found for young people to employ their leisure time. It would be the means of

fostering a love of study, inasmuch as children leave school before their

thinking powers are greatly developed, and they require some subject as a

connecting link between the subjects adapted to the capibilities of boys and

men; and I believe that starting with a fair knowledge of Welsh would open

the field for more extensive reading.

Tes; for I believe it would improve the Welsh children in English and in

Welsh.

Yes. After reading the "Elementary Eeport" you sent me carefully

and studiously, I was surprised to find these gentlemen

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 125

differ so much upon a subject which ought to receive more attention from

every true Welshman.

I sometimes, and now often, write on the board colloquial Welsh expressions

for translation, and I iind the children soon pick up the idiom in English.

But there is no time for a teacher to take this method too freely, as his

labour is not acknowledged; for a Welsh teacher would not willingly pass over

false orthography in Welsh. But apart from benefiting the children in Welsh,

I am of opinion I could teach them English more thoroughly by such a method.

Would bs welcomed by many teachers as a boon, both to themselves and the

scholars, as the teaching of Welsh would be less laborious in Welsh schools

than other subjects now taught; and it would thus, to a certain extent,

relieve the over-pressure which now exists in Welsh district.

By taking Welsh as a "specific subject," the time (and labour)

spent in conveying English instruction through the medium of the vernacular

tongue (as is the case in the great majority of Welsh country schools) might

be turned into direct pecuniary advantage. The mental training it would

produce would be of considerable '^educational" advantage.

It would be a moral advantage. By the omission of the teaching of it in

school some children are led to regard their mother-tongue as being something

to be ashamed of, and (Dic-Shon-Dafydd-hke) to be forgotten and cast aside as

soon as possible. 1 beg to state that I heartily approve of some such scheme

as your "Honourable Society " has suggested, provided it undergoes

some modifications. Text-books should be provided for all the standards —

conversational dictionaries, somewhat like the book of the Rev. Kilsby Jones,

Llanwrtyd, with enough of work for one year. Unless you limit (a work for

each standard, to form a foundation to the next standard), the superstructure

will collapse, and Her Majesty's Inspectors will annihilate the

"plan" and the teachers. I have adopted that method of teaching

EngUsh through the medium of the Welsh for about fifteen years. If I had

text-

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

126 WALES AND CHAP. IV.]

books we could succeed better. We simply use the black-board for half an hour

daily. We take special care with the irregular verbs, pronouns, moods, and

tenses. We make lists also of idiomatic phrases; those stumbling-blocks are

unsurmountable to the Welsh children but for the above method of elucidating

them. I do not approve of preparing a "specific subject" to be

examined in Welsh; I think there is ample work to learn English in general by

some such means as above. But some method should be adopted too to measure

our extra labour, and to pay for it according to the results. I do not know

in what standard in the "Elementary School" you intend your Schedule

IV., Welsh, to be applied. Erom my experience of the labour required, yours

is too hard after considering the time we have at our disposal. There is a

vast difference between translating Welsh to English and English to Welsh.

Brilliant children wiU not do the former, while they can do the latter with

ease. So I would confine the latter to the 3rd Stage; but with better

advantages, such as home-lesson books, and the subject becoming honourable,

perhaps indeed yours could be adopted. * * The Education Department cannot

form an idea of the WBAB.Y WOBK of teaching the children to comprehend the

most commonplace words in a consecutive order. Should this scheme ever come

into a practical form, I would be glad to see in each series Bnghsh

diphthongs grouped together, according to their sounds in Welsh. I teach the

infants to read English in that way, using the phonetic system through the

medium of Welsh. I need not explain, you understand the system better than I.

I beg to thank your Honourable Society for labouring on behalf of us teachers

and our beloved language. " Oes y byd i'r iaiih Gymraeg."'*

It would be becoming, and also polite [to the Welsh] to allow them the use of

their much-loved language, and make it a " specific subject" for

schools.

I am afraid that but few men clearly perceive what immense advantage would

accrue from the introduction of the Welsh

* This long answer is inserted nearly entire through an error of the

compositor. Having heen set up in type I leave it stand.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 127

language into the Code as the thin end of the wedge. The subject should have

been well discussed in the Welsh newspapers and periodicals before soliciting

an expression of "opinion" from all teachers, &c.,

indiscriminately.

The introduction of the Welsh language, in Welsh-speaking districts, as a

special school subject, woiild greatly sharpen the intellects of the children

for the reception of moral impressions when in attendance at religious

services (inasmuch as the colloquial Welsh in all districts is very

imperfect), making them virtuous in hf e; and certainly accelerate the

acquisition of English. GLAMORGAN.

Negative — [Eight replies from districts, considered unsuitable for the

experiment.]

No. Generally speaking the answers to this question wUl, to a very great

extent, reflect the ability of the teacher to teach the Welsh language.

No. Neither H.M. Inspector nor parents would approve of it, and it would be

of no benefit to the children as a class.

The Welsh children of my district (Waunarlwydd, near Swansea) understand

Shakespeare better than they understand Islwyn. The teaching of Welsh,

therefore, would require much time. Because the knowledge of Welsh possessed

by some children is far more extensive than that possessed by others. Because

Welsh people in fairly good circumstances ignore the Welsh language and

discourage it in their children; such is the fact.

Children in the Ehondda speak Bnghsh habitually in the playground; this

results from the immigration of EngUsh people. Summary of Objections — (1)

Many refining influential English teachers incapable of taking up the

subject. (2) Many Welsh-speaking teachers quite unable to teach Welsh. (3)

Districts like the Ehondda too mixed; English increasing. (4) To teach it as

a "specific" would only add another burden to the already

over-taxed powers of the children. (5) Welsh too elaborately inflectional.

Suggestions— {1) That it be taken up in night schools. (2) That a suitable

set of Welsh readers for Welsh Sunday schools, with

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

128 WALES AND CHAP. IV.]

illustrations, be compiled to make the Welsh reading therein interesting and

attractive, thus utilizing Welsh teaching already in existence with great

effect.

No. Because the Inspectors do not allow children the privilege of answering a

question in "Welsh at present, although the Code stipulates that such a

liberty should be allowed. The great majority of Inspectors are bank

Englishmen, whose hobby is to stamp out the Welsh language altogether. There

would be great difficulty in concUiating the parents to such a course.

In this district (the Tstradyfodwg) we have scarcely any mistresses able to

teach Welsh; the masters, as a whole, would be able to do so. * * Bnghshmen,

as a rule, do not possess "very strong love" towards anything

Welsh, and rather than assist it would prefer crushing it under foot. As a

thorough warm-hearted Celt, I would gladly hail this new attempt at

perpetuating the old language, but cannot see any hope.

Afeibmativb — Tes; and not only at elementary schools, but I think that at

higher schools and universities it should have a place amongst the other

languages taken, and candidates for degrees, &c., should be allowed to

take it as an alternative language, just as they now can take French or

Latin, G-reek, &c.

Tes, to Welsh country schools. (1) Country teachers have often told me that

they have recourse to the Welsh language to make the lessons intelligible;

therefore, by its introduction into the Code, they would get some credit and

pecuniary benefit for labour which is now often unrecognised and unpaid for.

(2) It would materially aid towards securing Welsh Inspectors for Wales, who

can properly sympathise with Welsh-speaking children, and understand the

difficulties they have to contend with in grasping the subjects.

Tes. The children attending my school are not conversant with the language,

although their parents are as a rule Welsh. This seems a pity. If Welsh were

taught as a specific, it would, in my opinion, be an inducement to Welsh

parents to bring up their children in the mother-tongue. Again, it would be

the means of aiding those who are already Welsh-spoken to obtain an accurate

|

|

|

|

|

|

[OHAP. IV. HER LANGUAGE. 129

knowledge of their language. It is to be regretted that but few in comparison

can speak and write Welsh properly.

Having been the head master of, probably, the largest schools in the

Principality for a period of over forty-one years, and having observed the

comparatively little change in the use of the Welsh language among the

resident population of this district during that time, I venture to express

my decided opinion that " advantage would result" from the

introduction of Welsh as an optional "specific subject.''

Yes. I beUeve it could be taught with great advantage. I find it easier to

teach French to a chUd who knows Welsh. The meanings and allusions in the

reading lessons are better understood in many cases where the explanation is

given in Welsh. Enghsh boys and girls strive to learn it if they hear the

teacher explain the reading matter thus, and the petty jealousy between the

races diminishes.

Yes. Welsh children naturally speak Enghsh veiled in Welsh idioms. This is a

great obstacle in the way of teaching English effectually. The introduction

of the study of the Welsh language into our elementary schools would give

teachers an opportunity to teach children how to translate properly. As a

consequence the children would learn to express themselves in purer English.

I feel certain that much advantage in every way would result therefrom;

chiefly, the intelligence of the children would be greatly improved thereby,

and school would be more of a pleasure to them. I know that these things

would follow from their having done so in my school by my taking my upper

standards through a Welsh grammar side by side with an English one, and I

have no doubt but that it would be the case to a much greater extent were

Welsh taught as thoroughly as it would be, were it a paid subject.

Yes. The knowledge, intelUgence, and the thinking powers oi the children

would be increased immensely; instead of their being as they are at present,

learning everything by rote.

I am not a Welshman, but I sincerely appreciate your intention.

I have always felt a desire to introduce Welsh as a "specific

B

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

130 WALES AND [CHAP. IV.

subject" into my school. My experience as a teacher enables me to

confirm Professor Powell's remark, "that the "Welsh language is a

powerful agent of education." * * It is a mistake to think that our boys

and girls will become better Englishmen and Englishwomen by ignoring what one

recently called " our beautiful "Welsh."

Although I do not understand "Welsh, I am of opinion that a grammatical

knowledge of their own language would be a much greater advantage to the

Welsh working classes than most of the ordinary specific subjects.

I find it easier to teach French to a child who knows "Welsh.

Our pupils s^ieak fairly good English but very bad Welsh. (My experience

extends as far as "West and North Pembrokeshire and the Glamorgan

"Valleys.) (1) It would be a good mental discipline.

(2) It would tend to accuracy in expressing ideas. (3) It would enlarge both

vocabularies (English and "Welsh). (4) It would give an excellent

opportunity for learning the idioms of th English language. Welsh teachers

have quite enough to do in preparing for the G-overnment examination, and as

Welsh counts for nothing at the certificate examination, it is of course

neglected. To remedy this some good Welshmen should establish classes in

connection with the Welsh colleges, and the Welsh professors should hold

periodical examinations and grant diplomas to those who have attained a

certain standard of excellence. As Welsh is learnt noiv it is simply a

hindrance to progress in English, and consequently in aU other subjects of a

common school education. Schedule I"V. More stress should be put on a

thorough knowledge of the accidence and syntax, and also on the idioms in

translation.

Advantages: (1) The usual mefital discipline in the systematic learning of

any language. (2) The language would in the future be spoken in a much purer

and more correct form than at present.

(3) It would stimulate patriotism, so necessary to the well-being of the

community. (4) The realisation of the "prophetic dreams" of our old

bards. (5) Being placed amongst the specifics there is no possibility of its

interference in the acquisition of English, which is of such vital importance.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 131

Much is said about " cultivating a taste for reading." I cannot

conceive of a better aid. Children in this district read Enghsh in the Sunday

schools untU they are about thirteen or fourteen years of age, then they prefer

the "Welsh classes. Objections: Masters are not capable of teaching the

subject. The Code demands too much already. Many inspectors I am afraid would

be unfavourable to it, hence disheartening those who would take it up. There

are diilerent opinions with regard to the merit of our literature, but I iind

that those who read "Welsh as well as Enghsh (although they are lovers

of Milton, Shakespeare, "Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Morris) feel they

cannot aiiord to neglect Hiraethog and Islwyn.

Netiteal — The English language ought to be taught in "Welsh districts

(such as Anglesey) the same as any foreign tongue would be taught — viz., by

means of the vernacular. I beheve that if the children were systematically

taught the English language instead of picking up what little they do by

accident, that in twenty or thirty years a revolution would have taken place

in the mental condition of the people. Eor this purpose we would have to go

in for a Welsh Code (optional, as some schools in Anglesey, and most in other

parts, such as Grlamorganshire, would prefer working under the Enghsh Code).

* * As a "Welshman, I am afraid that such a course would accelerate the

death of our dear "Welsh language, and gwell fuasai genyf hyny na

gwrthod allwedd fawr pob gwybodaeth i blant ein gwlad.

MONMOUTHSHIRE.

Nhgatitb — No. I consider that its introduction would result in greater

"over-pressure" in schools in "Wales. Managers would insist

upon its being taken up in all schools to increase the Government grant.

Ai'MEMATiTB — Yes, as it would be a great assistance in teaching Enghsh to

the "Welsh children. From my twelve years' experience as teacher in

"Welsh districts, I have found it necessary to impart my instruction by

means of the "Welsh language, and I know that the knowledge of the

Enghsh language, which is gained by the

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

132 WALES AND [CHAP. IV.

Welsh as a channel is far more sound and perfect than that which is acquired

by leaving the Welsh entirely out of the course of instruction. In spite of

the prejudice which some of H. M. Inspectors hare against Welsh, I have never

failed to give the children as much instruction as time would allow me in

their mother's language.

Most decidedly. It ought to be an extra subject in every school.

My children, although they were instructed first in English, but now being

able to converse in Welsh, would be benefitted by a further knowledge of the

Welsh language, and to the Welsh it would be a greater advantage.

The educational advantages would be very great, and surely the adoption of

such teaching would add a delightful work to many a Welsh teacher and scholar

and help to keep "yr hen iaith" alive.

To the scholars themselves it would give a sense of reaUty to grammar which

the subject does not now possess. And by its giving a power of comparison it

would greatly facilitate the teaching of historical English. The great

drawback is the ignorance of Welshmen of the grammar of their own language. I

may state that the vUlage in which I Uve has four EngUsh places of worship

and six Welsh ditto, the size of the latter being to the former as two is to

one.

Tes. Those of my scholars who read with true expression have a knowledge of

the Welsh langnage. They are certainly ahead of those possessing no such

knowledge.

It is the case in this school, which numbers over 200 children, all Welsh

except eight. I frequently use Welsh to explain difilcult terms, and the last

school report contains this remark: "The very intelligent work of the

three highest standards is deserving of special mention. * * Many look at it

now with contempt and as a thing to be forgotten; if introduced into school

it would be looked at in quite a different Ught.

It does seem very unscientific to attempt (more correctly to continue) to

make Welsh children learn English by UteraUy gulling them with it. We hear

much of "bi-lingual difficulty."

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 133

This I don't admit; the "difficulty'' is altogether in the means used to

teach EngUsh.

I heard the advocates of an alteration in the present system of Welsh

education spoken of lately by a person who had been a Carmarthenshire

teacher, as a "few agitators." The answers that are given above

will sufficiently disprove such a crude assertion, at least for the recent

date of 1885. Persons who make similar statements, and adopt a hostile

attitude, are frequently either Welshmen who have, through an imperfect

education, had to suffer disappointment in some way or other, and blame their

language instead of the system, or else persons who are really in good

degree, ignorant of the language, at least from a literary point of view.

Bearing in mind that we are not deaUng with the views of impractical

enthusiasts, but with the opinions of practical men, although in fact they

had no experience of systematic teaching of the language, except in a few

isolated cases, also bearing in mind the magnitude of the changes which might

be expected to take place in the event of the bilingual system being

universally adopted, I subjoin further summaries of leading points in the

answers, which may enable the reader to obtain a still clearer view of the

arguments for and against, than would be obtained by a cursory perusal of the

foregoing pages.

EEASON POE. BBASONS AGAINST.

WouIdassistinacquiringEnglish. Would hinder EngUsh conversation.

In Welsh-speaking districts in- Children would have to unlearn

telligent farmers wish their colloquial Welsh.

children to write Welsh letters.

Parents' desire for children to Parents would object.

write Welsh letters.

English hoys try to learn it when Would isolate Wales from com-

teachers explain in Welsh, plete assimilation with England.

and race jealousy diminishes.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

134

WALES XSB. CHAP. IV.]

BBASON EOE.

"Would be a pecuniary, an educational, and a moral advantage.

Young people noiv unable to compose Welsh letters.

(Successful teachers use Welsh freely.

Would aid in securing inspectors who could properly understand the

difficulties of Welsh children.

Children could then be taught to translate properly.

Stimulative to the mind.

English children insist on speaking Welsh every chance they get.

Means of mental disciphne — systematic knowledge of great value.

Should be compuisoby on all

SCHOOLS.

English taught more thoroughly thus.

Would require little extra work.

Children would be greatly delighted.

Would foster a love of study.

Open the field for more extensive reading.

Would induce parents to bring up their children in their mother-tongue.

Easier to teach French when Welsh is learnt.

Would enlarge both vocabularies.

Especially [wanted] where Welsh is likely to be forgotten.

EBASON AGAINST.

Want of utility.

"Sunday" schools and literary meetings provide for it.

Some successful teachers do not understand it.

Inspectors rank Englishmen.*

Present Code gives sufficient

latitude. Language too inflectional. English predominant in certain

district.

Most teachers ignorant of Welsh, and would require special training.

Because a special Code for Wales is wanted worst.

* It would not be fair to speak of the Inspectors of 1891 as rank Englishmen.

There are now notable exceptions to the old rule, but the Department is not

yet sufficiently alive to the advantage of having Welsh-speaking Inspectors

and assistants, even in bilingual districts.

OHAP. IV.]

HER LANGUAGE.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

135

PEEDICTED EESTTLTS OF PROPOSED SYSTEM.

Would create a thorough love for higher education and science.

The study of it would giye full command of a beautiful and expressive

language.

Would be an introduction to a classical education.

Would keep alive the Welsh national spirit.

Welsh literature would gain immensely.

Would relieve over pressure.

Would sharpen the intellects of the children for the reception of moral

impressions during preaching.

[Under a Welsh Code] in twenty or thirty years a revolution would have taken

place in the mental condition of the people.

It will be admitted that if we except, on the negative side, the parents'

objections, induced by what Carmarthen (61) styles "a popular

delusion," and the much more reasonable fear of overpressure, or

inability to keep pace with the then requirements of the Code in other

respects, that the affirmatives had an immensely preponderating weight of

evidence on their side, tending to strengthen the opinion that there were solid

grounds for introducing Welsh, experimentally at least, as a specific

subject, and in some places as a class subject. It is to be feared that the

Education Department, with their inspectors, have done but little to remove

the popular delusion referred to. Yet, one of the primary objects of

education is to improve the judgment, weaken superstition, and healthily

expand the

* This was written under the old Code, but doubtless is still true to a large

extent in Wales.

EESTJLT OP PEBSENT SYSTEM.

Present mode has lamentably failed except to a few.

Parrot-hke knowledge of English in most elementary schools.

Many "Sunday" school scholars does not distinguish between i'w and

yw.

Best teachers groan under drudgery of the Code.*

Present methods dreary and unnatural.

Welsh as a written language going into disuse.

"Present slipshod way of teaching, or rather not teaching English.

Children ashamed of their

mother-tongue. Weary work.

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

136 WALES AND [CHAP. IV.

mental-powers, in attaining which latter object competent judges allege, as

will be seen in this chapter, that the present system of ignoring Welsh is

sadly defective.

As a matter of fact, School Boards, composed in many cases of persons of

narrow or inferior education, continue, apparently, satisfied with results

which, although fairly good in contrast with the rest of the country, are by

no means the best attainable under a more intelligent system.

Considerable excuse however, must be made for many of these, because it is

not long since, as we have seen, the "Welsh note," was in use in

certain schools, so that the meaning of the term education in the minds of

many teachers, as well as parents, who observe how necessary a knowledge of

EngHsh is for purposes of material advancement, rather excludes the idea that

Welsh may at the same time, if properly handled, be made a powerful

instrument of education in the correct sense of the term, conducive to habits

of correct speaking and thinking, and supplying, in conjunction with English,

a means of mental disciphne even to boys in elementary schools, far superior

to that evinced by the present "sUpshod," hap-hazard, rule of

thumb-way, in which there is ground for believing many Welsh children think

and speak.

Even in semi-Anghcized districts where the mother-tongue of most of the boys

is English, but they are more or less familiar with Welsh, either by hearing

it spoken, or by connection with the religious denomination their parents

belong to, a course of Welsh can be introduced in the higher standards,

without much, if any strain on the teacher, as has been practically proved

where the experiment has been tried. Any other bilinguistic training involves

far too large an expenditure of time and talent to be at all practicable in

elementary schools. The attempt would, intellectually speaking, be

|

|

|

|

|

|

[chap. IV. HER LANGUAGE. 137

expensive. It is held that a bilingual method as advocated here would, in the

same sense, be remarkably cheap.

It should be borne in mind, too, that the objectors were speaking for the

most part of what they had not tested by actual experience, and veiy few of

them have done so, even up to the present time. This is true of the

affirmative, but the onus of proof, to shew that such a proposition should

not be tentatively adopted, lay with the negatives, which proof they failed,

on the whole, to establish.

Although I am somewhat anticipating my subject, I may mention the singular

fact that while theoretically the most thoroughly Welsh schools in Wales

would seem the most to need instruction in the language, in the practical

working out of the idea, it is in bilingual districts where English prevails

more or less largely, that the teachers or school Boards have shewn most

willingness to make the necessary changes, for instance, Ruabon in North

Wales; Merthyr, Gelligaer, Mynyddislwyn, in South Wales; while the teachers

in the country around Merthyr, which is more Welsh than the town, have

opposed the scheme. There are, however, one or two exceptions such as Llanarth,

in Cardiganshire, but this was previously an exceptionally well taught

school, and though in a thoroughly Welsh district, is ahead of most in Wales

or England. Probably this peculiarity is due to the fact that hitherto we are

only dealing with Welsh as a specific language taught to the higher standards

only, and it corresponds to the idea of one teacher— "especially where

Welsh is likely to be forgotten."

To resume now the thread of our history, very soon after the Cymmrodorion

Society had drawn up their reply, giving teachers' replies in extenso, the

National Eisteddfod in Aberdare, of 1885, was held, and presided over by Dr.

Isambard Owen: it was decided to form a Society for promoting the utilization

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

138 WALES AND [CHAP. IV.

of the Welsh language in education, and agreed to leave the organization to

Dan Isaac Davies. D. I. Davies, B.Sc, was a Sub-Inspector of Elementary

Schools, who had served the Education Department some years in England, and

then returned to Wales under the impression, as he expressed it, in 1887,

that he should find the Welsh language fast receding, almost disappearing,

but "at every step since my return on the 1st October, 1882, rather more

than four years ago, I have found the Welsh language has turned the corner,

and it has passed out of the time of, we may say an English teaching

reaction, I am glad to say not into a time of Welsh teaching reaction, but

into a time of bilingual teaching reaction."

In his earlier life it appears that D. I. Davies was inclined to depreciate

Welsh. He called himself an "Anglophile," but now at once threw

himself heartily into this movement so contrary to what had been for years,

the general current of education feeling in Wales, and so contrary to the

traditional policy of the Department in London.

As an illustration of the character of the opposition that was evoked, I vdll

quote the Western Mail, 8mo " Aug." 28th, 1885, which, in the

course of a long leader, remarking on the increased facility which it was

said systematic instruction in Welsh in day schools would give to the

children in understanding sermons etc., said —

"We were rather surprised to find in a report drawn up in the interest

of a people so determinedly opposed as the Welsh hare been represented to be,

to all religious instruction in their day schools the statement that,

"by accustoming the children to correct Welsh, it would greatly improve

their understanding of the religious instruction given in that

language." This, if it mean anything, means that an adoption of the

Committee's recommendation, that Welsh be taken as a specific subject in the

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 139

day schools, must eventuate in a tremendous accession of strength to the

Sunday schools.

Tlunk of that, you Nonconformists. Here is a champion of the Established

Chm-ch fearing that if systematic instruction is given in your language, a

"tremendous accession of strength" will accrue to your schools.

At the meeting in Aberdare above mentioned, a somewhat singular scene took

place; D. 1. Davies said that Tudor Evans (a CardiflF architect) —

Had impugned the action of the Committee of the Cymmrodorion Society in

appealing for information to the teachers of Wales, and had said that other

persons ought to have their say. There was a strong feeling that he, as one

of those other persons, should come forward, and have his say now.

Mr. Evans, who occupied a front seat in the body of the hall, and who

resolutely declined to comply with repeated appeals made that he should

ascend the platform, said he was not prepared that morning to be immolated on

the altar of bigotry (Cries of "Shame")!

D. I. Davies did not remain satisfied with the initial steps to organize this

Society, he wrote a series of six letters to the Western Mail on the

"Utilization of the home language in Wales," in the last of which

he said —

"We owe an apology and an explanation to our readers. We have seldom

written to the Press, and lay no claim to literary ability and yet we have

ventured to take up their time. Our life has been devoted to the spread of

Enghsh in Wales, and yet we have felt compelled to say a word for Welsh in

the interests of our people. Our University degree proves that our own tastes

flow in the direction of exact mathematics and science and not towards

literature and languages, and yet conviction urges us to plead, however

imperfectly, for a side of education which better qualified men should have

placed in its true light. We are personally disposed to

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

140 WALES AND [CHAP. IV,

think that Welsh should be used as a frequent means of illustration in

teaching the infant classes and lower standards, and taught as a specific

subject in the upper standards, the secondary schools, the Colleges, and the

University, and not as a means of teaching English, and yet see that we ought

to give a patient hearing to those teachers who claim that English can only

be taught efEectively in "Welsh-Wales through the medium of Welsh. We

feel that we must rest our case on purely practical educational arguments,

and fear not the result of any fair experimental trial of the plan we

recommend, yet our Cymric heart cannot help glowing at the thought that the

fair trial asked for will show that the practical utility of to-day and the

ancient glory of our race or nation (whichever "Gwyliedydd" may

prefer) will be found to be inseparably bound up together. Some of our

poetical countrymen are fond of making touching references to the death of

the Welsh language. * * * Infinitely to be preferred to the sentimental,

cruel tenderness of those who love to contemplate the agonies of what they

think to be an expiring language is the healthy, inspiriting advice of Dean

Vaughan, which we take from the valuable volume referred to in Letter III.: —

' I take things as I find them, and I presume to say that the one hope for

Wales of to-day, her one hope of learning, or of influence, or of usefulness,

is that at least she be bilingual. No nation ought to part willingly with her

distinctive speech. She ought to cUng to it with all fondness. The only limit

to this tenacity should be that which common sense and self-interest conspire

to impose upon it. If the language isolates her from all nations, if it risks

her cosmopolitan character, as the disciple of the wise and the instructress

of the ignorant, then, and then only, should she accept the omen, and make

the very best of the inevitable. But what then? Is she to fling away the

speech which was her differentia among the nations? Only treachery and

cowardice would counsel it. She has a patriotic and a religious duty stiU

towards the tongue in which she was born. She has, first, to see that it be

articulately and grammatically formed and shaped in all its particulars, so

that

|

|

|

&&

|

|

|

CHAP. IV.] HER LANGUAGE. 141

it shall be no patois of chance and trick, but a language worthy of the

respect of other languages, worthy to become the study of the learned and the

training speech of the young. Next, that it shall have a literature all its

own, a literature without a knowledge of which the education of a scholar

shall be confessedly incomplete — a literature unapproachable sare through

its language, and, therefore, securing to that language the undying interest

and unstinting eSort of all who would think or know.'

Bear in mind, readers, that a literature is "unapproachable save through

its language." You ask for translations of Welsh literary eflfbrts.

Learn the language and translate them yourselves — that is in effect, the

advice of a leading representative of the Established Church, not a

representative of what has been tiU lately its leading policy, but a

representative of the views of a minority represented, we may suppose, by

such names as Gwallter Mechain and Silvan Evans.

D. I. D., himself formerly a teacher, makes an eloquent appeal to those with

that calling and responsibilities —

Day school teachers of Wales! Tour opportunity has arrived. Tou complain from

time to time that you work hard for the nation, where no one sees your

self-denying exertions which, it seems to you, are in danger of being too

little appreciated. How has the Cymmrodorion Society treated you during the

last year? Has it not supplied you all vidth a report of its preliminary