..

|

|

|

|

|

338 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

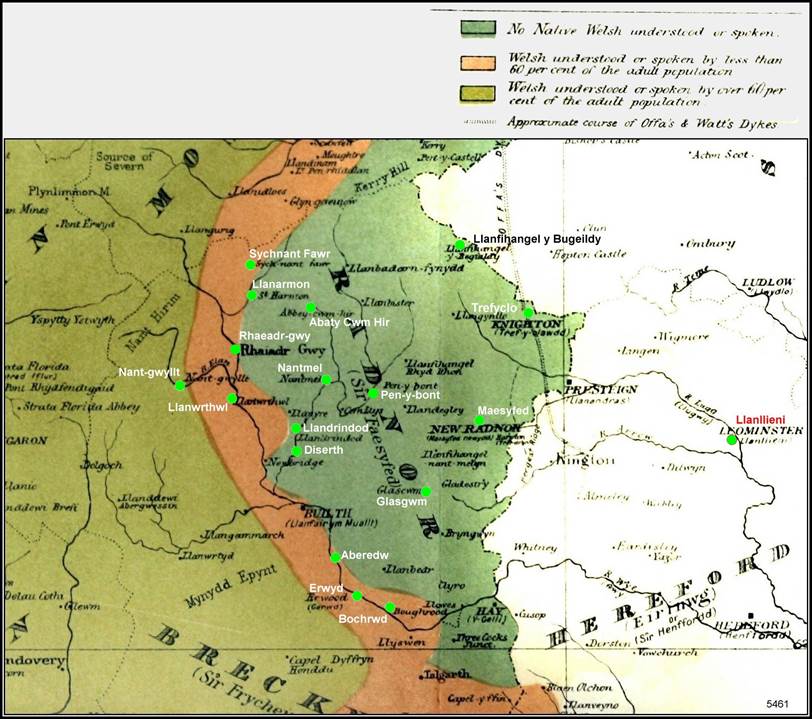

only 800 inhabitants, is one of the principal towns of Radnorshire, in a wild

district, 17 miles from the English border, and about as far from Offa's

Dyke, yet very little Welsh is spoken there. A correspondent, well-known in

Radnorshire, says:-

Welsh seems to have steadily died out in Radnorshire; and the reason, unless

it were the ill-success of the Calyinistic Methodists here — the Baptists

seem to have been generally English, — is difficult to ascertain. Kerry, I

suppose, fell away from its proximity to Radnorshire.

In this parish, Nantmel, there are two Welsh-speaking people just above me;

but both originally came from

Llangurig in Montgomeryshire. There may be a very few on the other side of

(S.) Harmon parish by Sychnant-fawr (marked in your map) and Waun-cilgwyn,

and there are perhaps a dozen old people in Rhayader who prefer Welsh, and

many others in trade who can speak to the Breconshire, Cardigansh,

Montgomerysh, and Cwmdauddwr (top part) parish, Radnorshire (right bank of

the Wye), Market people. * * * There may be a very little occasional Welsh

preaching in Sychnant Calvinistic Methodist Chapel, but people come there

from Llandinam and Llangurig parishes in Montgomeryshire somewhat. * * * Even

on the right bank of the Wye all the way down Welsh is only understood, not preferred or generally

spoken on the side of the hills nearest the river. Until 10 years ago perhaps

Welsh was generally spoken all over the upper or western parts of the

parishes of Cwmdauddwr, Radnorshire, and Llanwrthwl, Breconshire, but now

even there English is prevalent. About five years ago the last purely Welsh

(Baptist) minister of the last place of worship in Radnorshire where only

Welsh was preached, resigned, and his place was filled by one half Welsh and

half English, and hard by there is an old Episcopalian chapel — Capel

Nantgwyllt * * where the service has long been half and half. The Methodists

have occasional purely Welsh worship and preaching at a farmhouse higher up.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] WALES AND HER LANGUAGE.

339

It is somewhat singular that at a Baptist Association meeting at Rhayader, five

summers ago, preaching was carried on in Welsh to some five thousand people,

many of whom were no doubt from Welsh parts, but many more cannot have

understood a word. Among the latter was a poor man whom I heard talking to

his mate the next day and expressing his admiration of the language.

The authority above referred to, S. C. Evans-Williams, of Bryntirion,

Rhayader, gave an interesting address at Knighton, bearing on the question of

the Welsh language in Radnorshire, in the spring of 1891, from which the

following is extracted —

A thought which occurred to him in connection with the Welsh character of the

eisteddfod —that was the decay of the Welsh language in the county of Radnor.

Few, perhaps, realised the fact how short a time ago, there in this town of

Knighton and neighbourhood, it was since Welsh was the vernacular language.

He had lately been getting up a little of the subject, and he found that in

the year 1730, in the neighbouring parish of Beguildy — which they knew was

close on the Shropshire border — the Welsh language was used for Divine

service once a month in the parish church. That showed that, down the very

border, the Welsh language was at any rate used nearly half and half with the

English. The next period they had any information with regard to the subject,

which he had been able to find, was in an account of a lawyer who went from

Bridgnorth to Llandrindod Wells just at the middle of the last century. He

said, in his written account, that after leaving Knighton the whole way to Llandrindod

he crossed commons or waste lands, and was not understood by the natives —

neither did they understand him — so it was impossible for him to ask his

way. A Mr. Lewis Morris in 1794 [?] paid a visit to Radnorshire and described

that visit. He spoke of the Welsh tongue being used at that time in every

parish church [!!] in the county, and he further said that in Penybont at

that time the Welsh language and the English were spoken equally by the

|

|

|

|

|

|

340 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE]

[CHAP. IX.

people. The people talked better Welsh and far better English than their

neighbours in Montgomeryshire. At the same time in Glascwm both languages

were spoken, and in New Radnor Welsh was the prevailing language. That was

1747. So that the Welsh language

appeared to have died out very gradually, travelling towards the west. In the

parish of "St." Harmons only 50 years ago Welsh was divided with

the English as the language which was used in Divine worship. He had pretty

well worked out a theory that the Welsh had gone out to the west as the

English advanced; but lately he had received a pamphlet by Mr. Ivor James, of

the Cardiff College, in which he seemed to say that he believed the English

prevailed in the Principality 200 years ago more than the Welsh language. It

thus appeared that the Welsh language had rather driven out the English,

after the Civil Wars, from the country which previously it had generally

possessed. Mr. James gave Radnorshire as one of the principal instances, and

said that the cause of the prevalence of English in Radnorshire — which was

so marked among the counties of Wales — was that the English language had

never really been driven out by the Welsh in the 17th century, during the

beginning and to the middle of which the English language prevailed in Wales

more generally than was supposed.

Ivor James' explanation of the prevalence of English in Radnorshire may be

correct, but it does not quite commend itself to my mind. It is scarcely

likely that English and Welsh existed side by side for so long amid a very

scant population without literary culture, when probably most were unable to

read. My friend, S.C.E.W., says himself that the reason is very difficult to

ascertain.

The result of personal enquiries at Penybont has been quite fruitless as to

any person with even a traditional knowledge of Welsh-speaking villagers

there. In the south-west of the county, I learn from a native that Welsh

still lingers in the neighbourhood of Boughwod and Erwood, but is extinct on

the east of the Wye at Aberedw.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 341

Several years ago I was acquainted with an old Radnorshire woman from Abbey

Cwmhir, whose recollections extended back to, say, 1810. In her youth the

parish was evidently a bilingual one, and farm-house preaching was partly

English and partly Welsh. One of the verses used in the neighbourhood began

thus —

Son am farw, son am farw, Clywir yma, dacw draw.

[= talk about dying, talk about dying, it is heard here (and) over there]

Another was an English doggerel,

How many miles, how many,

Is it from Leominster to Llanllieni?

Llanllieni, it may be recollected, is the Welsh name for Leominster, which

was for many years the Metropolis in which Radnorshire folk disposed of their

salt butter at the annual fair.

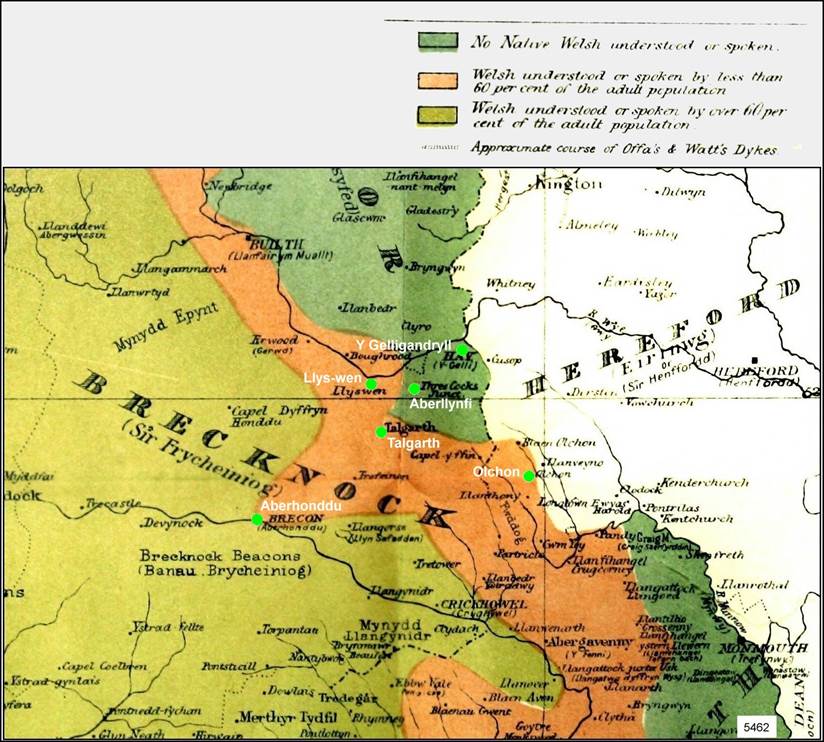

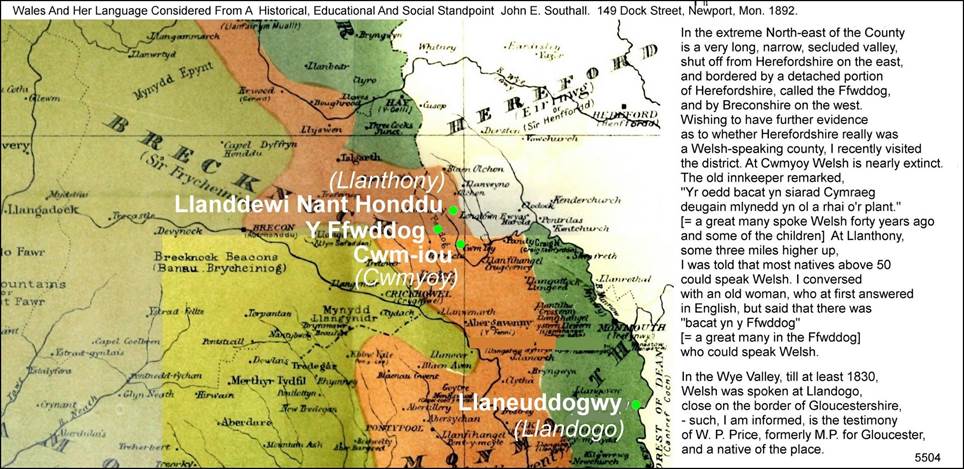

BRECONSHIRE. — I include the whole of the north-west of the county within the

linguistic border, which I take to enter the county about Llyswen, near Three

Cocks, thence to Talgarth, and thence it skirts the northern slopes of the

Black Mountain to Olchon in Herefordshire. In fact, nearly the whole of

Breconshire is thus included, though not much is spoken between Brecon and

Talgarth, and none, so far as my information goes, between Talgarth and Hay,

though in 1878 one or two old people at Glasbury, I believe, spoke Welsh.

HEREFORDSHIRE. — On making enquiries from a person resident near Longtown, I

was positively informed in writing that Welsh was understood only, by a

proportion of the population in Olchon, Longtown, and Pandy — apparently my

correspondent had written one-third. Wishing to satisfy myself, a personal

visit was resolved upon — not to wild Wales this time, but just to the east

of the towering, dignified Black mountain that I had so often gazed at in

childhood and youth,

|

|

|

|

|

|

342 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

CHAP. IX.

covered in the distance with a hazy mantle, which only brought to view its

dim, gaunt outline against the South-western sky, Pandy station, on the

borders of Herefordshire, being my terminus, I commenced operations in the

County of Monmouth. The first old man on the road conversed with me a little

in Welsh, but Radnorshire was his native place, and he had learnt Welsh at

Rhymney about 1850. I was, however, assured by John Davies, F.S.A., that

native Welsh was not quite extinct in that parish.

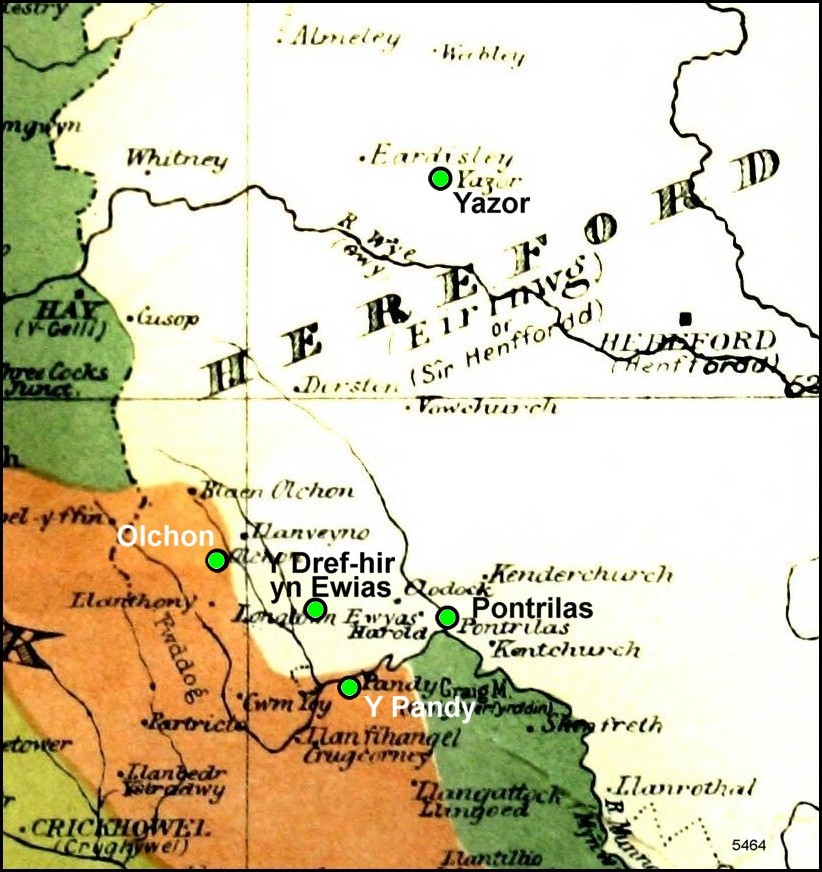

At Longtown, in Herefordshire, an Episcopalian preacher informed me that at

Newton, near Pontrilas, the children at the Board School were taught Welsh

songs.* In the village, of Longtown, however, I failed to meet a single

native who could converse in that language, but was told that "some sort

of Welsh" was spoken there about 30 years ago.

Still further to the North lies Olchon House, where a farm servant was found,

about 40 years of age, who said he could understand and speak a little, and

that a few people higher up could do the same. Strange to say, in that

out-of-the-way place, a Cardiganshire youth was working and assisting the man

with the sheep; he had come there to learn English.

"Sixty years ago you might go into a house by chance and hear nothing

but Welsh," was the testimony of an old farmer north of Longtown.

"They did not teach the children Welsh; I should like very much to have

learnt Welsh."

Now, how is it that the last flickering flames of a knowledge of Welsh still

lingers in South-west Herefordshire, while at Presteign, perhaps, we may say,

no one has ever known any one (a native) who ever knew any one — to put it

genealogically — who could speak the language. One answer to that question is

that it was for long years a place that nourished dissent.

* This is, of course, were taught to sing in a Foreign language.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 343

Go back to the fourteenth century, and take note of Walter Brute, a reformer

before the Reformation from this very district; remember the Lollard's

"chapel" in Deerfold forest some twenty miles to the north, and

Sion Cent, the Lollard monk-bard, going in and out of the halls of the

Scudamores, a few miles to the south; remember, again, that in the I7th

century one of the very earliest Welsh Baptist congregations was formed at

Olchon, that in 1794 the Cymanfa Ddeheuol was held there,* and issued their

circular letter, and even as late as 1875 or thereabouts one Morgan Lewis

occasionally preached there in Welsh.

The valley of the Olchon, and that of the Honddu both belonged to the Wales

of the Welsh Bible, and perhaps of Canwyll y Cymry, but they have never

belonged to modern Wales — to the Wales of Y Traethodydd, Y Drysorfa, and Y

Dysgedydd, of Gwilym Hiraethog, and of Brutus, nor even, to that of William

Williams, Pantycelyn.

As I left the spot the sun still lighted the top of the grand natural barrier

which towered up in majestic dignity on my right, while to my left lay the

fertile vales of Herefordshire — a rare junction of the wild and the stern

with the fruitful and the mild, of the mountain with the lowland.

At Clydach, on the way back, an intelligent old peasant, John Gwilym, told me

that his grandmother could speak Welsh. She was born, say, in 1767, so that

about 1790 children at Clydach and Longtown were beginning to be monoglot

English. Now Clydach lies close to the border, but there is a much more

remarkable case than that of Welsh speaking in Herefordshire. Some years ago

I knew a Welshman in Newport, who assured me that about 1835 he had conversed

in Welsh with the mistress of a farmhouse at Yazor,

* Llyfryddiaeth y Cymry, 1794. No. 23.

|

|

|

|

|

|

344 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

CHAP. IX.

on the north bank of the Wye, 8 miles from Hereford, who assured him that in

her childhood the children generally spoke Welsh there.

On first thoughts from a comparison of these facts, especially when we learn

that in the city of Hereford* in 1642 many people spoke Welsh as a native

language, it would seem that the history of the language was that of gradual,

though constant retrocession to the West. There is some truth in this, but,

on the other hand, there is reason to believe that the Saxons early settled

at Withington and Ashperton, within some 12 miles of Hereford, and that

Thinghill represented the meeting-place of their local council. This cannot

have been much later than the ninth Century — if so, the exterior boundary of

the English must have continued nearly constant for several centuries. We can

understand a Welsh district in a county keeping up its characteristics for a

certain time (as probably in the case of the Peak country, Derbyshire), but

how it should have done so to such an extent as at Yazor, where the children

must have grown up Welsh-speaking for nearly 1000 years after the Saxons had

approached within some twenty miles is a marvel, especially when we recollect

that the palace of the great King Offa at Sutton, lay near Hereford.

South of the Wye, in the districts of Ewyas (Euas) and Archenfield (Erging)

around Ross, the population in the middle of the fifteenth century must have

been nearly solidly Welsh speaking. It was during that period that Lewis Glyn

Cothi addressed an adulatory ode to a squire named Winston, at Whitney-on-Wye, near Hay, in which he speaks of him

as a patron of the Welsh language.

As late as circ. 1707 we find E. Lhuyd speaking of Eirinwg (Herefordshire) as

an habitat of the Gwenhwysaeg dialect of Welsh.

* Diocesan History of Hereford, S.P.C.K. series.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 345

I shall have a little to say about present day Welsh in a detached portion of

Herefordshire, under the following heading:—

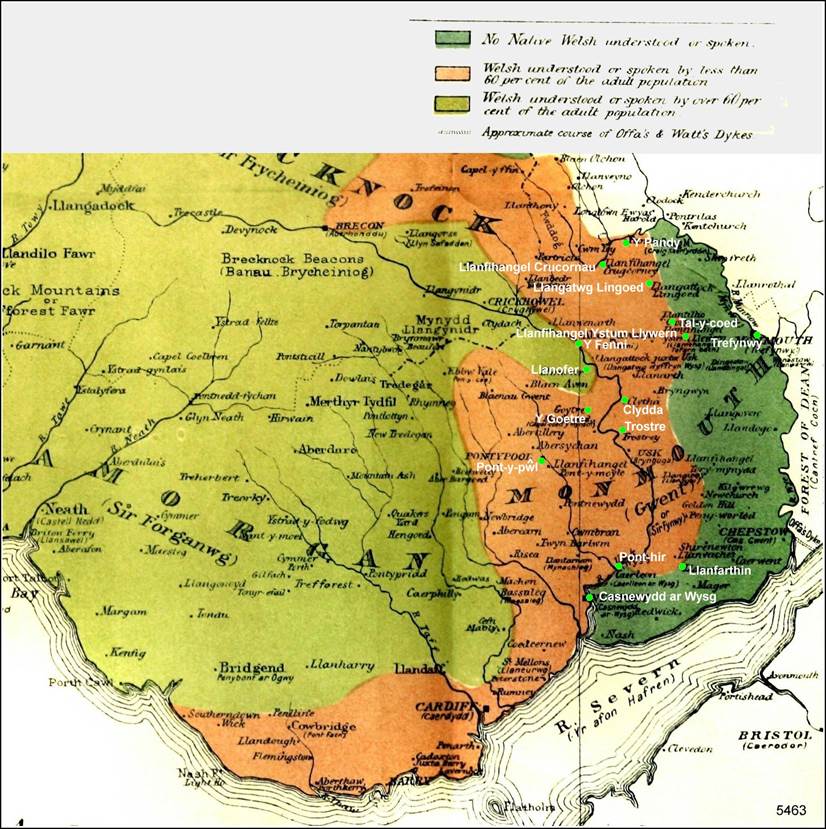

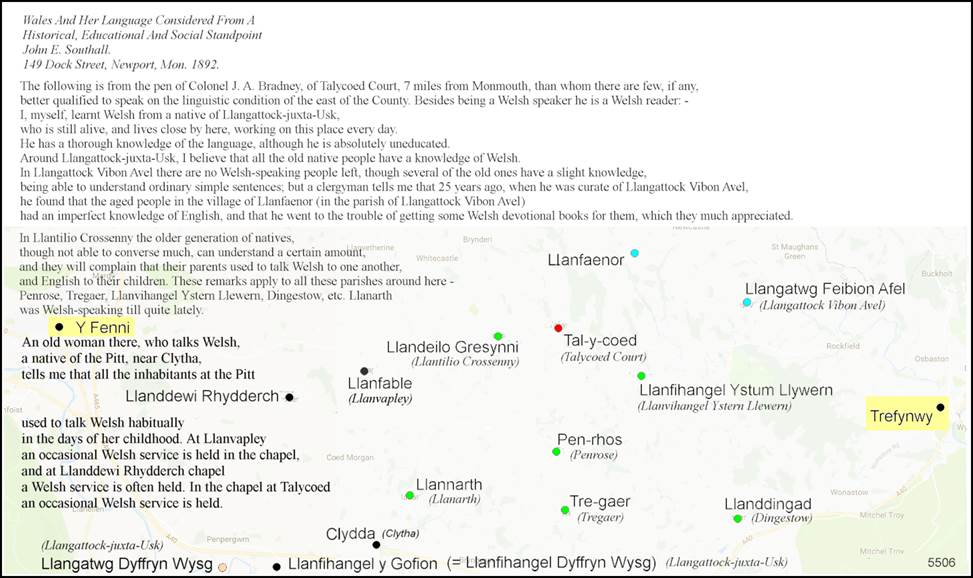

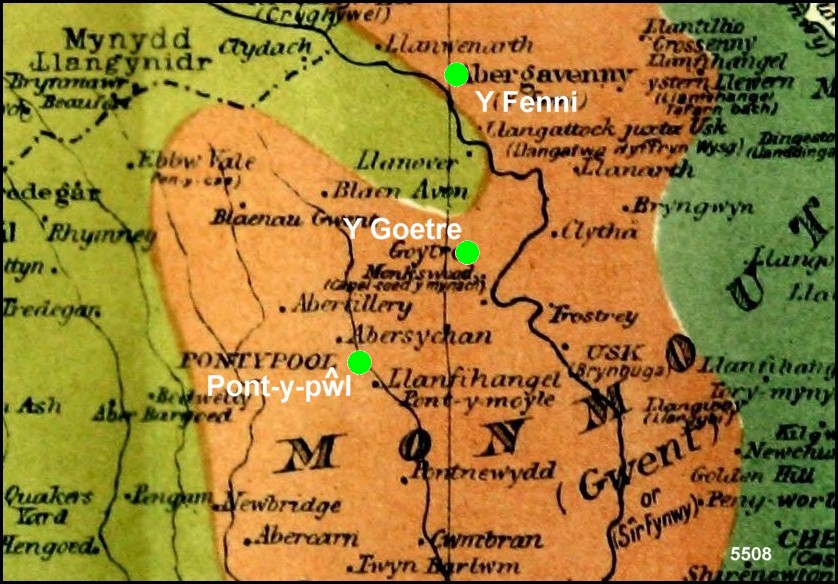

MONMOUTHSHIRE. — The linguistic boundary enters the county between Pandy and

Llanfihangel stations, on the Hereford and Newport railway, thence to

Llangattock Lingoed, Llanfihangel Ystern Llewern, a few miles North-west of

Monmouth, thence to Clytha and Trostrey into Newchurch parish, and as far

South as Llanmartin, thence nearly due West to Ponthir, thence to Newport,

but not including Caerleon, thence to the mouth of the Usk, the west bank of

which may still be considered to be Welsh speaking.

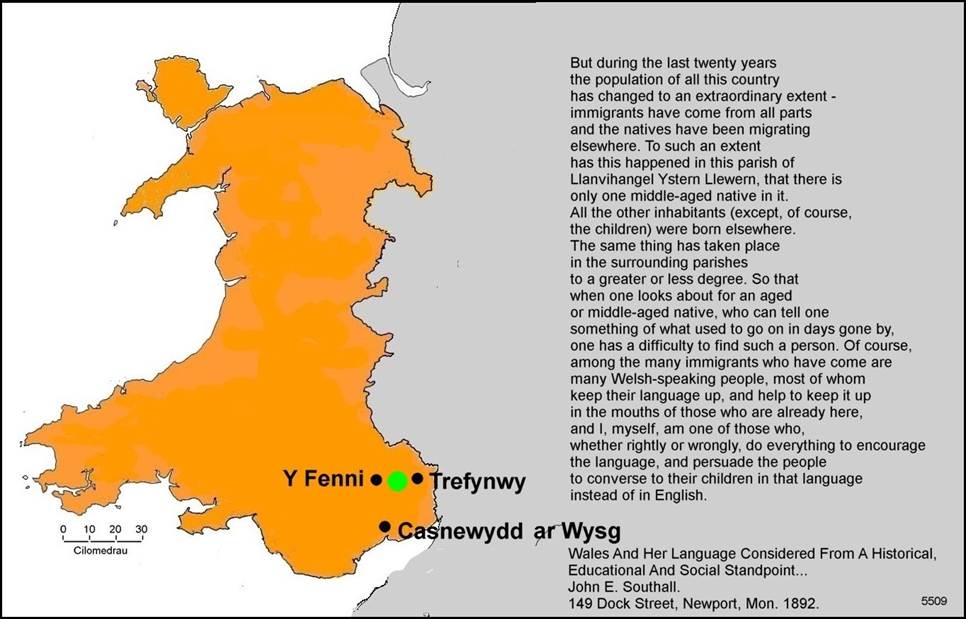

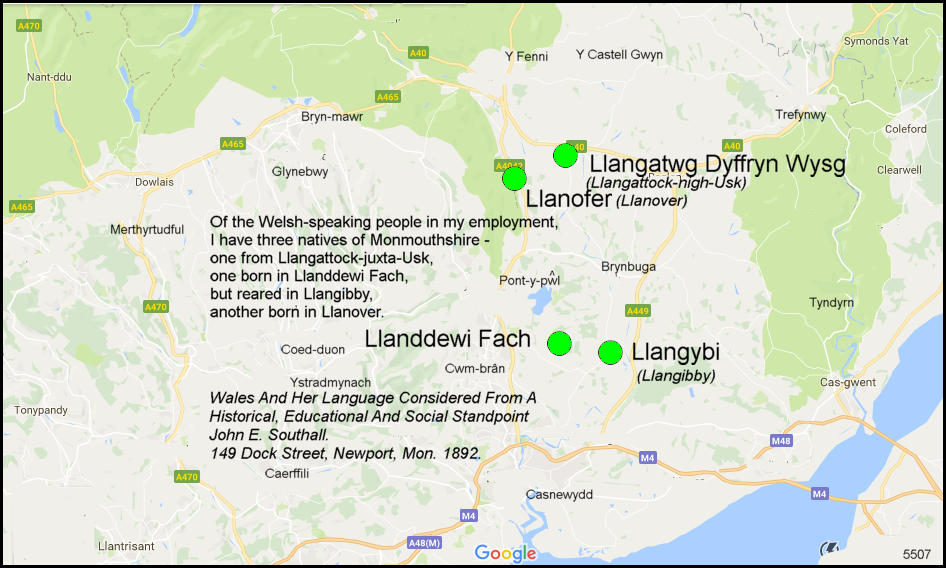

The valley of the Torvaen, from Pontypool to Ponthir, is inhabited largely by

newcomers or their descendants to the third generation. Native Welsh is,

however, not quite extinct in it, although there is no Welsh preaching

between Pontypool and Newport. In Goytre and Llanover, between Pontypool and

Abergavenny, Welsh is generally understood by a considerable proportion of

the inhabitants. In fact, at the latter place, it appears that the children

can mostly speak it, to judge by the testimony of Coedmoelfa, a North Walian

residing there, —

"Mewn attebiad i'th ofyniad ynghylch iaith y plant yn Llanover, Cymry yw

y rhan fwyaf a Chymraeg a siaradant."

[= in response to your request about the language of the children in

Llanofer, most of them are Welsh and it is Welsh that they speak]

How is it that here remains an island of green not yet swallowed up by the

advancing tide of red? The answer is not far to seek, and is found largely,

if not wholly, in the influence of Llanover Court; supposing an English

squire had settled there 60 years ago and introduced English stewards and

English servants into the district, what would have been its linguistic fate?

Of course, it is well-known, that under the rule of Gwenynyn Gwent (the Lady Llanover), the very contrary has been

the case, and that the village school of

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX ] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 349

by men's hands and that His Spirit could be coerced or cajoled by

architectural magnificence to give them the smile of His favour, or that they

were thus in some way likely to be nearer heaven than the poor Welsh

goatherds or shepherds, who climbed the mountain side and braved the blasts

of winter in pursuance of their duty. Llanthony disappears, and a few minutes

hard walking brings me to the top of the ridge, surrounded by the heather and

the mountain breeze, far away from the screech of an engine or the smoke of

furnaces, while the face of external nature is nearly the same, minus the

goats and deer, as it was six centuries ago, when the monks told out their

beads in the valley below.

Slightly to the right rises the Skirrid (yr Ysgyryd) while to the west and

south-west near and distant mountains meet the eye. In connection with one of

these — Pen-y-Fâl, a landmark for many miles into England, and called by the

Saxons the "Sugar Loaf,”* Gwallter Mechain wrote a fine awdll [sic; = awdl] (ode) for the

anniversary of the Abergavenny Cymreigyddion, in 1837. Poetry and history are

here blended together, as he alludes to the different features of the

magnificent prospect before him, —

A dangos mor glos yw Gwlad

Mynwyson:

* * * *

Edrychaf o'm deutu, ar Loegr a Chymru,

A ddichon neb gredu mor wiwgu

mae'r wedd?

Rhaid gweled i goelio, mi geisa'u

darlunio,

Cyn yr elwyf fi heno i'm hannedd.

[= to show how beautiful (tlws, feminine adj tlos;

clws, feminine adj clos) the country of the Mynwy people is:

I look around me, at England and Wales,

How can anybody not believe the appearance is so

splendid?

It is necessary to see to believe, I’ll attempt to

portray it (geisia’u = portray them should probably be geisia’i = portray it)

Before I go this evening to my dwelling]

Far in the distance is Gloucester,

nearer to hand Llantarnam, the ancient residence of Ioan ap Rosser, then he

notices Goodrich Castle, the home of a Welshman, Samuel Meyrick, Llanover

* Think of introducing the ideas of a grocer's shop in connection with such

an object, grand in itself and grand in its surroundings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

350 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

then Hereford, and the Malvern Hills. Over the Severn he sees Somersetshire

and Devonshire, and would see Cornwall if fair weather and the rays of the

western sun combined. Nearer Varteg, Blaenavon, the three Monmouthshire

rivers and Raglan Castle, where instead of "moethus Gloddesta"

(dainty feasting).

O heno! gwelir gwahaniad — ceir cân

Dylluan yn

gwawdio y lleuad! Neu greg Frân anniddan ei nad — liw dydd,

Ar ei gilydd yn rhuo galwad!

[= Oh tonight! a division is seen – there is the

song of the owl deprecating the moon! Or the hoarse crow with its dejected

cry – by light of day, noisily calling each other (at + each other + roaring

+ a call)]

The Brecon and Carmarthenshire beacons are not missed —

Acw y Bannau

Teir-fforchiadau;

Hwyntau'r Mynnau, dasau dwysir

Cestyll rhuddion

Haeniau cysson

Saerniaeth ION, argoel ion [should be argoelion] gwir.

[= over there the Bannau (Brecon Beacons),

three-forkings; they [are] the ‘Mynnau’ (?mannau = places), the stacks of two

counties; red castles, neat strata, the craftsmanship of the Lord, true signs

/ omens]

This ode does not follow the rules of Dafydd ap Edmwnt, but rather those of

Glamorganshire. Perhaps it is not nearly the best piece Gwallter Mechain

wrote, but to those who know the district it is not only of interest, but

there is nothing in English to approach it as a lyric of the hills; yet how

many young men in the neighbourhood of Abergavenny or Newport to whom Pen y

Fâl is a familiar natural object, can read it?

GLAMORGAN. — The extreme boundary of Welsh only occurs in Glamorganshire, in

the Gower Peninsula, between Pen-clawdd and a little north of the Mumbles.

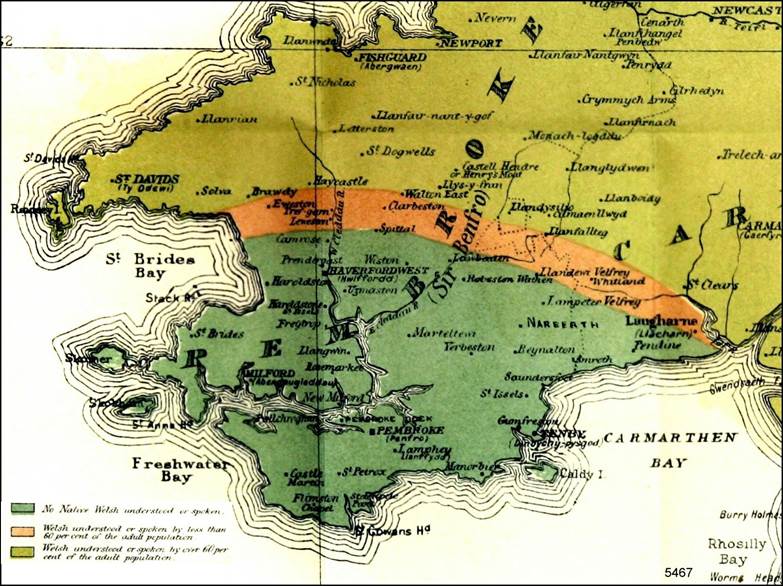

CARMARTHEN AND PEMBROKE. — Carmarthenshire is wholly within the Welsh

speaking area, excepting a very small portion in the extreme

South-Western corner, between

Laugharne and Amroth. It will be observed that the exclusively English part

of Pembrokeshire, runs slightly to the north of Lampeter Velfrey, Lanhawden

and Spital— the extreme boundary,

|

|

|

|

|

|

352 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

neighbours in Wales, and yet for one class to know but little of the

circumstances of the other as to their language. I believe that very few

County councillors of Monmouthshire, have much accurate knowledge of the

distribution of the language in the County.

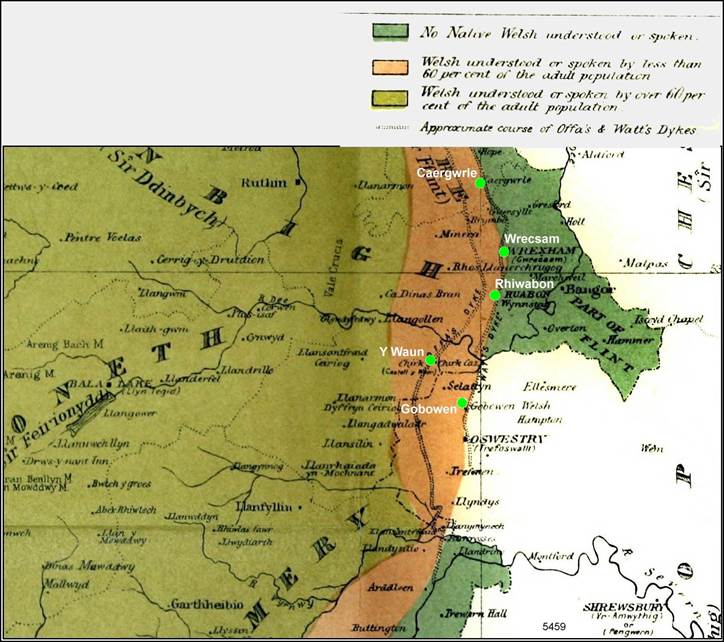

The 60 per cent, boundary is naturally one which must be rendered

theoretically, there being no precise data on which to work, I take it to be

generally within ten miles of the extreme boundary, until it enters the

valley of the Usk, near Brecon; it expands to a width of fifteen or twenty

miles in Monmouthshire.

It will be observed that a considerable portion of the South of Glamorganshire

comes within this limit, but it is comparatively contracted near Swansea and

in Pembrokeshire, had I constructed an 80 per cent, limit it would in reality

have differed very little from the 60 per cent., but it would have cut off

most of the rest of Monmouthshire, (except the Nantybwlch corner,) the

Merthyr, Aberdare and Rhondda Valleys, and South Glamorgan, with two or three

towns, such as Carmarthen, Neath, and perhaps Aberystwith.

Llandovery is well within the 80 per cent, limit, and probably will continue

within the 60 per cent, for some generations, or at least 60 per cent, of its

population will be included in classes I.- VI. (see a few pages further on)

but I find that the amount of Welsh literature sold there, has much fallen

off during the last ten or twelve years. In fact, English is stealthily and

surely eating its way into the heart of Wales in that direction, and

conversational Welsh will soon be a small factor in the social life of the

district. Whether this is due to the influence of country Squires, who

delight to rouse the country, to see dumb animals ridden round and round a

given course of ground, or not, I will not attempt to determine.

Space does not permit me to minutely discuss these boundaries,

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 358

the boundaries of the past, nor the present condition of some places which

offer features of interest. If however I was asked the question — where would

be the outlines of a map drawn up in a similar plan for 1485, at the

accession of Henry VII, I might reply that the green portion would have come

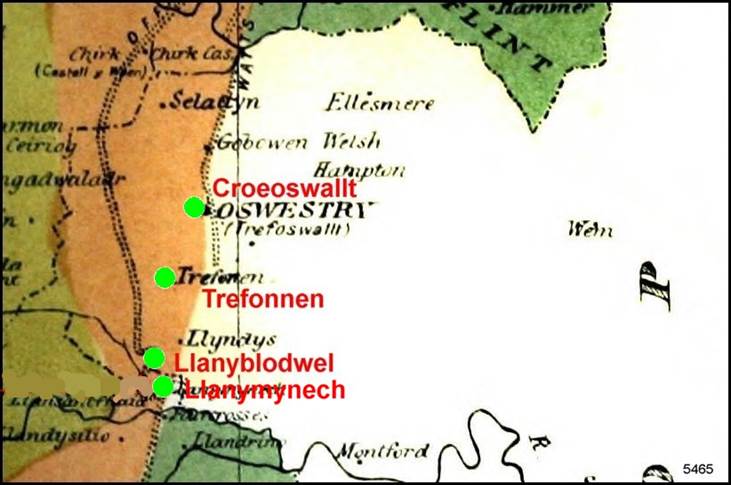

as far east as Oswestry, but am doubtful if it would have covered Hawarden (Penarlag*) in Flintshire. It would

have included Clun Forest in the south-west of Shropshire, and nearly the

whole of Herefordshire west of the Wye, and north and east of the Wye from

Yazor to Leintwardine, and some part of the Forest of Dean (Cantref Coch). As for the red it was

probably very narrow in Cheshire and Shropshire, but more extended in

Herefordshire and Gloucestershire, reaching nearly, if not quite to

Gloucester Bridge.

I omitted to state under head Monmouthshire, that the results of my visit to

the Ffwddog (Heref) established the fact that native Welsh exists there,

although I heard of no children who can speak it.

OFFA'S DYKE. — What schoolboy has not heard of Offa and his Dyke? What

grown-up person of culture has not met allusions to it in books? But who has

seen it? The tourist on the Cambrian or the Central Wales, or on either of

the West Midland branches of the Great Western? In the great majority of

instances, the same negative answer would have to be given as if passengers

on the North Western or Midland or North Eastern expresses to Scotland were

asked if they noticed Hadrian's wall or that of Antonine lying across their

line of route.

To tell the truth, Offa's Dyke — where it is not entirely obliterated — is

generally not particularly noticeable. Perhaps the very best and most

complete portion extant is situated

* In the map Penarth halawg (= the salty headland) but Penarlag is the usual

name.

|

|

|

|

|

|

304 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

about 1½ miles south of Knighton, some

little distance away from the main road. With a monoglot English-Welshman as

my guide, the identical man who had some time before lamented his ignorance

of the vernacular, I climbed the slope of an eminence leading to the spot,

and before long reached what my companion considered to be traces of the

dyke, which simply formed a broad basis to the hedge, about three feet wide,

and barely raised above the level of the ground. "I must see something

more convincing than this," thought I. There was not long much room for

doubt: a little further on was a deep towering bank, some twenty feet above

the bottom of what still bore the character of a trench or hollow on the

western side.

Here my companion left me, I sat down, and thought of the time, as hazy to

the mental view, as the western hills facing me, when instead of a carpet of

green grass mingled with the dry stalks of last season's herbage, nought but

bare freshly-turned soil would have met the view.

Then, again, who were the labourers — were they defenders of their own lately

gotten soil, or were they forging against their own liberties the chains of a

foreign yoke?

They have perished; history is silent, but numbers them in the band of the

great unknown, the work of their hands yet remains, that of their hearts we

know not.

They have perished; and so have the armoured knights who crossed and

recrossed this very dyke, sometimes in league with the Norman-English,

sometimes with the Cymric Princes of the soil. And, then, what of the

mothers' sons who lay weltering in their blood, whose sighs and groans were

wafted by the wind to their comrades in combat. What of those who crossed

never to return?

Such considerations as these were present on my mind while nature round

whispered peace. Freedom and industry

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 355

are now allowed a dwelling-place in the land, but the dark passions of

humanity have not changed, covetousness and cruelty have found other refuges

than the donjon and the keep. Never before, too, had I realized the magnitude

of the undertaking: even with the appliances of the nineteenth century, it

would be no child's play to construct such an earthwork from the Dee to the

Wye, if the bank near Knighton is a fair sample.

About one mile further on, the dyke assumes comparatively insignificant

proportions, as it crosses the main road between Presteign and Knighton.

Now, who was this Offa, who caused the dyke to be made? — He was a King of

the Mercian Saxons or Angles, who had married a daughter of Charlemagne; but

he was also a murderer, and a violator of the rights of hospitality. Under

the persuasion of his queen Quendrida he murdered Ethelbert King of the East

Angles, who had come as a guest to demand his daughter Adelfrida in marriage,

and afterwards conquered his country. The Pope promised security from

punishment on condition of his being

liberal to Churches and Monasteries.

What did he do to atone for such a black crime? — He became one of the chief

pillars on which rests the legal claim of the most numerous religious sect of

this country, to Tithes. To atone for this murder, he gave away a tenth part

of the produce of the labours of unborn men, i.e., to compensate for one

wrong, he thought to buy the favour of heaven by committing another wrong, in

its ultimate effects and tendency far worse than the first. Don't

misunderstand me, the murder he confessed and knew was a horrid crime; the

giving away of tithes was an act done in the name of religion which tended to

spread a false idea of what religion is.

Who has any right to devote any portion of the result of the labours of

unborn generations to any such purpose? What

|

|

|

|

|

|

356 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

body can truly and honestly call this their property, and give the name of

spoilers and robbers to men who seek to divert such income into the National

treasury?

Offa's Dyke is shewn on the map as far south as Almeley, thence, I should

estimate its course approximately through Vowchurch and Kenderchurch,

crossing the Wye a second time at Lydbrook, near the boundary of

Herefordshire, thence through the Forest of Dean to Beachley near Chepstow.

The Census. — A material help towards elucidating the geographical distribution

of Welsh in Wales, and the proportion of inhabitants speaking it, would have

been afforded by the Census of 1891, had the resolution of the British House

of Commons, which virtually required a return of all persons in the

principality who spoke the language, been carried into effect. Instead of

honestly endeavouring to ascertain this by sending Census papers with the

column to be filled up with the required information, to every household in

the principality, the authorities took upon themselves, to some extent, to

decide where to send papers with this column: such a course did much if not

entirely vitiate in some bilingual districts the trustworthiness of the

returns which at the moment of writing, are not yet published. In Newport,

Mon., for instance, a batch of papers were actually sent to the First day

("Sunday") school of a Welsh Congregation, for this column to be

filled in there; whereas it is manifest that many Welsh speaking persons

would not be in attendance, and one woman was threatened with a fine of £5 if

she did not take an English paper, in other parts of South Wales, similar

inefficiency was observable. Whether the bungling that attended the Welsh

Census was the result of ignorance, or whether the authorities were unwilling

that the total number of persons who might fairly be credited with ability to

speak Welsh should be known, I will not attempt to decide.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 357

Patagonia.— Welsh has been spoken in the New World, probably ever since William

Penn left the shores of our country on his first visit to the infant colony,

which justly gave in his eyes and those of his friends a bright promise for

the future. Many of the first settlers of Pennsylvania, were Welshmen,

seeking a peaceful asylum from the harassing outrages of informers, evilly

disposed justices and clerics in their native country; some of them were of

the poor and obscure of this world, others came of families of local note and

position, who notwithstanding their Quaker convictions preserved genealogies

for a succeeding age.* Traces of the nationality of these settlers are to be

found in Pennsylvania, in such names as Merion, Brynmawr, Uwchlan, and

Radnor, some, or all of which, are situated in what used to be known as the "Welsh

track." The Welsh of the United States, is however, now spoken by much

more recent comers, or their descendants, and is principally to be found in

the iron districts of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York, and among

agricultural populations in certain parts of the Western States.

Where, however, the language appears likely to find a more permanent home is

in the valley of the Camwy,# in Patagonia. A hundred and fifty Welsh settlers

were landed there in the middle of winter 1865. Without sustenance from the Argentine

Government, the enterprise would probably have many years ago been added to

the list of unsuccessful colonizations, as for a considerable period the

colonists had to endure at times, hardships, privations and losses, until

they not merely discovered that irrigation would be the secret of success,

but found means to carry it into operation. In 1886, a canal forty miles long

was made, and in 1889, a railroad the same distance;

* Dr. J. J. Levick, of Philadelphia, among others, has interested himself in

these matters, and has published some of the records of early settlers.

# Chupat river.

|

|

|

|

|

|

358 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

in the same year wheat from the Colony gained a gold medal in the Paris

Exhibition, the amount raised yearly, being no less than ten thousand tons.

When we consider that the total population is only three thousand souls, and

their wealth was estimated in 1890, at one million sterling, it may be

anticipated that they have a future before them. The proceedings of the local

council are carried forward in Welsh, which is taught in seven out of eight

schools, the other being a Spanish school, and now that a printing press is

established in the Colony, it is to be hoped that the deficiency in Welsh

educational works suitable to elementary education, will be in some way

supplied.

Continued ill success, naturally was the means some- years ago, of spreading

black reports about the country: the following written by a Welsh traveller,

gives another side to the picture, —

"I have seen as many lands as it is almost possible for one of my age to

have done, yet truly none yet please me as well in every respect as an

'Andine Wladfa.' New Zealand and Southern Chili come nearest in beauty of

scenery and natural excellence generally, but in neither of these can we hope

to hear the old language amidst surroundings so natural to it. Streams,

rivers, cascades cataracts, falls, and lakes meet the eye in all directions,

the whole combining to form a most romantic picture."*

Havhig in an earlier portion of this work noticed the position of the

different social classes in Wales, with regard to the language and having now

dealt with its geographical distribution; we will proceed to consider a

classification of the general population into those sub-divisions which

the presence of two languages induces

under the natural laws of association and thought, as well as under conventional

influences; such as classification will in the particular case of

* From the South Wales Weekly News.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 359

Wales, enable us the more easily to appreciate the forces at work.

The linguistic classes, form in fact, the nett resultant of a variety of

forces, foremost among which are two antagonistic ones, viz.: — that

occasioned by the support given to a foreign language, by governments past

and present, and the vis vitae of

the vernacular in the hearts and minds of the people. In thus dividing the

total population, i.e. that is those who have passed through school life,

into linguistic classes, I do not assert that such hard and fast distinctions

actually exist; individual cases may for instance exemplify more than one

division, and between each division there are as many gradations as shades of

colour in the material world.

We find then in Wales the following: —

I. Monoglot Welsh — able to read the language: from this class have come some

writers whose names are treasured in the archives of modern Welsh literature.

They are very fast disappearing, just as the class of Monoglot Welsh unable

to read the language, is now nearly extinct, therefore hardly worth

mentioning.

II. Semi-Monoglot — able to read Welsh well, also able to transact ordinary

affairs in English, which they can read a little, they are to be found in

every county in Wales, and form part of the amateur Literary Staff, which

creates and supports current Welsh literature.

III. Bilingual Welsh — who not merely can read the language well, and have a

greater literary mastery of it than any other class in Wales, but also are

familiar with literary English, and who with almost equal readiness read or

speak both languages. With the spread of education and the establishment of

National Colleges, this class has considerably increased of late years, and

its members have a vantage ground ceteris

paribus in acquiring the lead in professional and political life, not merely

|

|

|

|

|

|

360 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

and thoroughly Welsh districts, but also in others partially anglicized.

Owing however to the unthinking, ignorant way in which middle-class education

has been conducted, they have to be recruited principally from West Wales,

and from the midst of res angustae domi;

I don't like to say poor homes for that might appear to cast a slight on

poverty, especially when we bear in mind that their proficiency in literary

Welsh, and sometimes in other subjects is largely the result of self-culture.

Of course, were a national system of education in force, young men from such

districts as the Merthyr and Rhondda Valleys, would stand a better chance of

receiving those bilingual appointments which occasionally fall vacant. I

recollect a Government official in a responsible position in South Wales,

remarking to me, "I owe this to my father: when I came back from school

he spoke to me in Welsh, while I answered in English," implying that

thereby he had picked up sufficient Welsh to qualify him for his post. It

will easily be seen that under the present system at school and college every

nerve may be strained in thinking, speaking, and, writing English, while any

knowledge of Welsh that might have been acquired in early life lies dormant.

IV. Bilingual Welsh — who read and speak both languages, but whose reading

knowledge of Welsh is rusty, though not so much so in denominational

literature, this is a large class in South Wales.

V. Bilingual Welsh — who only speak a little and cannot command a free flow

of expression in that language, these are sometimes to be found among the

upper classes (so-called) as well as among the poor. I would include among

them those who speak the language but cannot read it, the latter are mostly

Episcopalians.

VI. Monoglot English Welsh — who can read the language more or less

perfectly, but cannot speak it, though they may

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 361

understand a little of it when spoken, these are principally to be found

among Dissenters in large towns, such as Swansea, Cardiff, Liverpool and

London.

VII. Monoglot English and English-Welsh — who can neither speak nor read.

Some neither know it, nor care to know, others would give many pounds for a

facility which might have been acquired in the golden age of childhood.

In spite of all that may be said as to the rapid Anglicization of Wales, its

having a dying language and the like, few things since my connection with the

country have struck me more than the extraordinary vitality of the language,

in the face of such adverse circumstances. This vitality is indeed wonderful

but it cannot stand before the mental pressure of an exclusively English

education and association, in the industrial districts. It may exist, perhaps

for many generations even there, but in a dwarfed, cramped, unassertive way

not as an important factor in the life of the people. In the counties

bordering the Irish Sea, however, the case may be different, it is possible

that the native education will sufficiently counter-balance the English

education to preserve a really bilingual people, able to avail themselves of the

information found in English books as well as in their own. If however the

educational system is "reversed" the results both in east and west

Wales, will soon give a very severe check to the process of entire

anglicization, and an additional impetus to the numbers of the above class

III.

I can scarcely be expected to close this chapter without reference to the

number of persons to whom Welsh is more or less familiar, Sir T. Phillips in

1847 reckoned it at 800,000! After the Census of 1871, Ravenstein calculated

that the number of persons habitually

speaking Welsh was 1,006,100 out of 1,426,514 in Wales* and

Monmouthshire. I believe

* Report of Intermediate and Higher Education Committee, 1881, p. xlvii. zz

|

|

|

|

|

|

362 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE.]

[CHAP. IX.

that since that period, there has been a decrease of the number of persons who

habitually speak Welsh, but an increase of those who either can speak it, or

habitually listen to it in connection with the different denominations. Some

years ago Sir H. H. Vivian stated that 870,220 (including children under ten)

used Welsh among the Nonconformists alone, and when we add to these the

Episcopalians and the Welshmen attending "English Causes," who draw

upon themselves the bitter irony* of some of their Countrymen, and those who

go "nowhere," I think the number would be in excess of Ravenstein's

estimate even now. In reality however, Welsh has reached a crisis, it is

tottering in a state of uncertainty whether to go backward or forward.

Without such reasonable extraneous help as is afforded every day to the

competing language, there is scarcely a doubt that it will have to succumb in

extensive and populous districts though not entirely there for some

generations, and perhaps not in West Wales for centuries.

There is every reason to believe that there are portions of Wales where the

Welsh language assumes an aggressive attitude at the present day; that is to

say, where it is becoming the mother tongue of families of English origin,

and bearing English names. I believe this is generally an easier process than

it otherwise would be on account of a large proportion of the new comers

belonging to the west of England, where Celtic blood is more abundant than in

the east, for instance, Welsh has spread to some extent among the Cornish

settlers at Llantrisant. Somerset and Devon supply a considerable proportion

of the English element.

I do not consider it at all the part of patriotism for Welshmen to disparage

or to obstruct the influx of new blood; provided

* Ond y mae clywed ambell i Gymro uniaith yn y wlad yn dweyd mai i'r

"Inglis côs jabel" y bydd ef yn myned, yn ein gwneud i'w gashau â

chas cyfiawn [? ]— but unreasonably intemperate — Essyllt in Y Cymro.

[= but to hear an occasional

monoglot Welshman in the country say that he goes to the

"Inglis côs jabel" (= attempted pronunciation of “English cause

chapel”) makes us hate him with a vengeance (‘with rightful hate’)]

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. IX.] [WALES AND] HER

LANGUAGE. 363

only that they take reasonable and proper care that their language receives

equal treatment to that of the strangers, the new blood will then tend to the advancement of the nation.

Principal Reichel, of Bangor, alluded some time ago in an educational

pamphlet to the difficulty of getting Welsh youths to think in English, as

though that was one of the aims and objects of his mission in Wales.

Now it is probable that educationalists of the future will not quite conform

to this model; what Wales really wants is educated men who know a little

Welsh, but think in English; and also educated men who are familiar with

English, but think in Welsh, and express themselves freely and idiomatically

in that language. When this is realized, there will no longer be any need for

the complaint as to illiteracy at the close of the following quotation. It is

a translation from an article in Y Geninen Vol. ix. p. 226, on "the

diflficulties of Welsh patriotism" —

Look at a boy in a day school, he is made an Englishman without knowing it.

His tender mind is moulded on an English model, and an English bias is given

to his self-consciousness. He is taught to respect England and not Wales. He

is taught in the language of England. He does not hear a word of Welsh from

the mouth of his teacher. * * The language of his father and mother is

banished from the school. A Foreign language is introduced instead of that of

the hearth. * * They are taught to know what is a noun, a verb, and an

adjective, and to form English sentences. They do not know what is an enw, a berf, nor an ansoddair,

they are not taught to pronounce nor to form Welsh sentences. An unavoidable

consequence is serious ignorance of the language. Only a few Welsh people can

write their language correctly. Nothing surprises anyone connected with the

Welsh press, more than the incorrectness of the written productions of our

ministers and public men.

|

|

|

|

|

|

364 WALES AND HER LANGUAGE. [CHAP.

IX.

Notwithstanding the above, it is singular how much Welsh people talk about

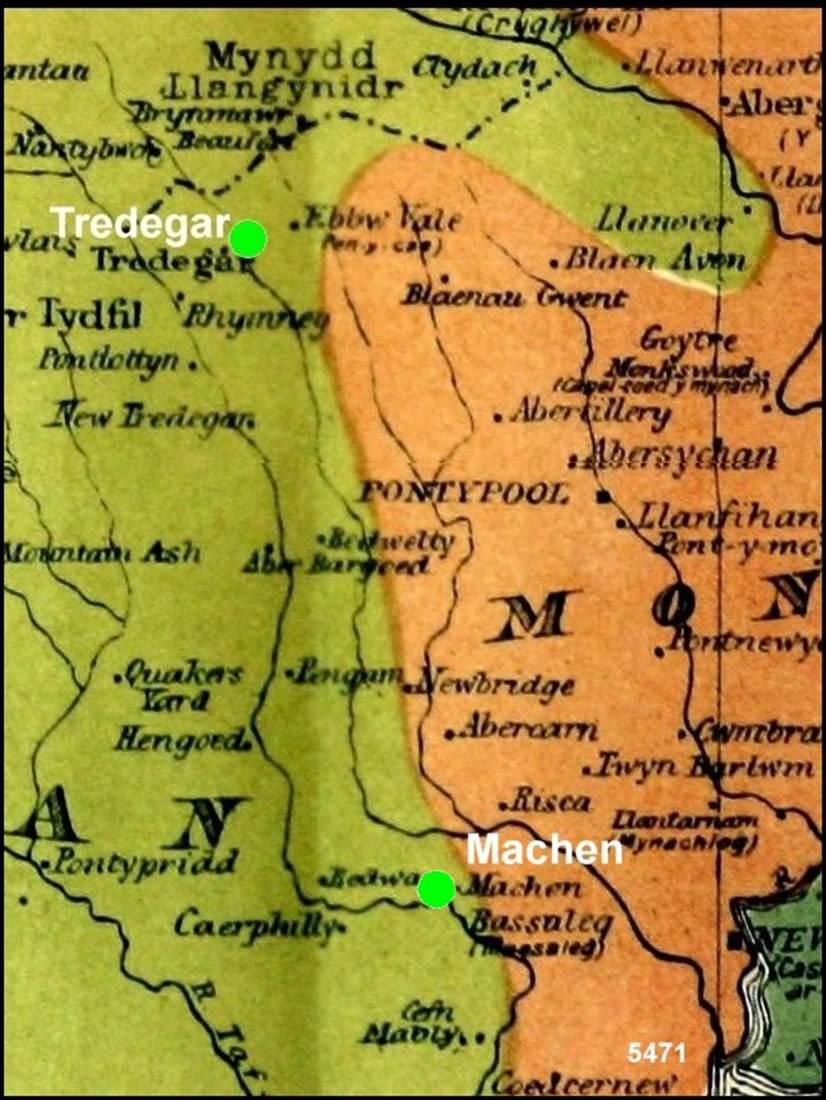

their language, and yet how little is said about the only availabletredegar

means to render it a common inheritance,

viz. — its introduction into school life. Here is an example taken from the

report (Adroddiad) of a Welsh congregation at Tredegar, (Mon.) for 1891,

which shews an increase not a

decrease of members —

"We strongly feel that disadvantages as to language form a great

hindrance which militates against the prosperity of the Church. This is

caused by neglecting to teach Welsh by the family hearth. We recommend the

advice of Mynyddog. Whatever you are doing, do everything in Welsh.' "*

Tredegar is inserted in the GREEN portion of the map, though I am somewhat

doubtful of the propriety of doing so. Out of twenty-six meeting houses in

the district, (including the Episcopalians') Welsh is only preached in

thirteen; but probably these thirteen contain the largest accommodation.

There are three Primitive methodist places. A traveller when he passes any of

these in Wales, may be pretty sure that an English population has been

imported from the Midland Counties or elsewhere.

It may be mentioned that the western boundary of Monmouthshire, runs nearly

straight from outside Rhymney to near Machen, just west of that town.

* Teimlwn yn gryf mai un rhwystr mawr ag sydd yn milwrio yn erbyn llwyddiant

yr eglwys ydyw anfanteision iaith. Achosir hyn gan ddiffyg dysgu'r Gymraeg ar

yr aelwyd gartref. Cymeradwywn gyngor Mynyddog:— "Beth bynag fo'ch chwi

yn wneuthur, gwnewch bobpeth yn Gymraeg."

[= I feel strongly that one great barrier which

militates against the success of the church is the disadvantages of language.

This is caused by the lack of learning Welsh in the home (‘on the hearth at

home’). We recommend the advice of Mynyddog – “Whatever you are doing, do

everything in Welsh”).

|

![]() Statistics for Welsh Texts Section / Ystadegau’r Adran

Destunau Cymraeg

Statistics for Welsh Texts Section / Ystadegau’r Adran

Destunau Cymraeg