.....

|

|

|

|

|

CHAPTER X.

CORNISH — ITS RAPID DECLINE — REASON THEREFOR — RELATION OF A LANGUAGE TO THE

MINDS OF THE SPEAKERS — IRISH — ITS DIFFICULTIES TO LEARNERS — IRISH LANGUAGE

SOCIETY — SCOTCH GAELIC.

A REVIEW of the decline of the ancient Cornish has -^ directly nothing to do

with "Wales and her Language," but it is introduced here, as

affording a sidelight on the position of the Welsh, and both to shew how far

the history of the two languages runs parallel, and how far important

differences exist, which must materially affect an estimate of the future of

Welsh, based on the history of the sister tongue.

Celtic scholars, who are well acquainted with the slender materials which

exist for such a digest as I am about to make, will, I am sure, excuse a

repetition, for the sake of the less well-informed. In rendering this, I

shall principally rely for assistance upon information given in Jago's "

Glossary of the Cornish Dialect."

We have already seen that in Wales, at the time of the accession of the first

Tudor Kings, there was a large amount of manuscript literature existing,

apparently more in proportion to the population than was the case in England,

and there is a probability the language was spoken both by feudal lords,

small freeholders, and serfs, over the whole of Wales (except portions where

alien colonies had settled,) and in parts of Herefordshire and Shropshire. At

the same period it is probable that Cornish was spoken a few miles over the

Devonshire border, (Devon-Cornish appears to have existed in Queen

Elizabeth's time), and that the whole country west of

|

|

|

|

|

|

366 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] CHAP. X.

the Tamar — the river dividing the counties- — was nearly solidly Cornish.

From the nature of the trade carried on by the inhabitants, there was

considerable intercourse with England in connection with fishing and mining

pursuits, and though there is no evidence that English was anywhere generally

spoken in the county before the art of Printing was introduced into England,

the vocabulary was gradually becoming less and less representative of a pure

Celtic tongue, something like the colloquial Monmouthshire Welsh of our day,

which is interlarded with English words.

However(,) this may be, no English was used in the old parish masshouses

before 1547, when the Vicar of Menheniot taught his parishioners the creed,

the Lord's Prayer, and the Ten Commandments in English.

Now, it is very remarkable that within the very short space of 60 years not

merely did it come to pass that English was generally spoken, but Carew, in

his "Survey of Cornwall," published in 1602 said, "Of the

inhabitants, most can speak no word of Cornish." About 1610, another

Cornish writer says: "It seemeth, however, that in a few years the

Cornish will be, by little and little, abandoned.” By 1640, Cornish appears

to have been excluded from all the parish meeting-houses but two, viz., Feock

and Landewednack.

Though such extreme rapidity at first astounds a person who has only been

accustomed to deal with the retrocession of the Welsh-speaking border, which

at one point — Oswestry — can scarcely be said to have moved three miles in a

century, on further consideration of the facts, the difficulties partially

disappear.

In the first place, Cornwall is not known to have had a national literature.

There was no Iolo Goch or Glyn Cothi or Dafydd ap Gwilym; no Triads, no

Cyfreithiau Hywel Dda,

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. X.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 367

no Mabiniogion to be read in the halls of the country squires. In the next

place, there was no translation of the Bible, and no religious literature

beyond the so-called sacred dramas, which were meant to be performed rather

than read. In the third place it was disused as a medium of communication in

public worship, at first apparently, because the people could understand

English, rather than because they could not understand Cornish. As to the

real facts of the case — historians are at variance: Whitaker author of the

"ancient Cathedral of Cornwall," affirming that the tyranny of

England forced the language on the Cornish, by whom it was not desired: Borlase

on the contrary says, — "that when the liturgy was appointed instead of

the mass, the Cornish desired it to be in English."

Now the truth probably is that a small minority of the people, represented by

such as the Vicar of Menheniot, desired the change of language, and that a

certain amount of coercion was used to effect the purpose desired, which was

remarkably successful owing to the combined effect of banishment from the

Episcopal worship and the absence of printed literature, though a much longer

period was required than from 1540-1640 before the conversational use of the

language entirely ceased.

The last Cornish sermon preached noticed in history, was preached in 1678. In

1701 E. Lhuyd noticed the language being retained in fourteen parishes, along

the sea shore from the Lands End to near the Lizard, by some of the

inhabitants only. E. Lhuyd managed to acquire sufficient knowledge of the

language to write a Cornish preface to his book. In 1746 a Cornishman was

found who could converse with Bretons. In 1758 the language had nearly ceased

in ordinary conversation. In 1788 Dolly Pentreath the last person whose

mother tongue was Cornish died, although there were others alive then who

could converse in it more or less.

We have just seen that there were surrounding conditions

|

|

|

|

|

|

368 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. X.

in the face of which no language could be expected to live; nor the

population speaking it, to partake of the civilization of modern Europe. In a

state of savagery, its preservation might have been possible; but Wales and

Cornwall have some 1600 years passed that stage of development. External

circumstances, then possibly accented by the policy of the Tudor governments,

starved Cornish to death.

Welsh still lives under differing external circumstances, and is likely to do

so for hundreds of years to come, as the starving process has only been

partially applied. It is one of the objects of this book to shew that such

circumstances may be so modified as to ensure it a natural, rather than an

artificial death; or else to indefinitely prolong its life.

The following is two verses of the First chapter of Genesis in old Cornish: —

Yn dalleth Dew a wriig nef ha'n nor.

Hag ydh ese an nor heb composter ha gwag; ha tew olgow ese war enep an

downder, ha Spyrys Dew rug gwaya war enep an dowrow.

The following is modern Cornish followed by the corresponding Welsh (see Arch

Brit p. 251) —

Bedhez guesgyz diueth ken gueskal enueth, rag hedna yu an guelha point a

skians oil.*

Bydd drawedig ddwywaith cyn tare unwaith, canys honno yw 'r gamp synwyrolaf

oil.

Breton the remaining sister tongue is more akin to Cornish than to Welsh. I

have no precise date as to the population speaking it — probably 900,000

would be near the mark.

Many people talk about a language as though it was simply a matter of choice

with the people which they spoke. This is

* " Be struck twice before striking once, for that is the wisest

achievement of all." This occurs in a curious old story, containing the

adventures of a Cornishman, fished up by E. Lhuyd.

|

|

|

|

|

|

OHAP. X.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 369

not SO altogether. The amount of the actual use of a language is m reality,

the resultant of several forces, the operations of which if they were capable

of being weighed and measured could be expressed by an exact mathematical

formula; as however, we can never reduce metaphysics into a branch of

physics, we will not make the attempt.

Though we can never arrive at an exact conclusion, we may still take into

consideration, the adaptability of the sounds and structure of a language to

the mental constitution of the people who speak it, in pther words how far a

given language is an adequate representation of the feelings, ideas and

mental powers of those who speak and write it.

The relation therefore which a language bears to the minds of those to whom

it is a mother tongue, is indicated by what may be called its statural or

substantial vitality. The effect produced by laws, custom and education

considered in themselves as exterior forces acting upon the use of the

language, may be called the artificial or accidental vitality.

The use of language is not a matter of choice with the generality of people,

simply because it is not an end, but only a means to an end. That end is to

express a wish, or communicate an impression to a fellow being with the least

possible trouble and leaving aside the action of the baser emotions, such as

pride, a person chooses that language to communicate in, of which the natural

vitality combined with the artificial vitality enables him most freely to

express his mind, and consequently produce the results aimed at, with the

least mental effort.

Suppose for instance a nation with a language which possesses a certain

correspondence with the expression of their own mental habits comes in

contact with another language possessing a less correspondence, we might say

that the natural vitality of the first language was greater than that of the

second,

|

|

|

|

|

|

370 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. X.

and up to a certain point notwithstanding the concurrent use of the second,

the speakers fall most naturally back upon the first. It is possible however

that the use of the second may through external or artificial causes so

exclusively predominate, that it takes root like the graft of a tree, the

balance turns the other way, the firstoccupies a secondary place, or it

gradually dies and its natural vitality is then only expressed by a tendency

of mind, to what naturalists would call " reversion," which waits

sufficiently favourable circumstances to assert itself.

The science of language has of late years received considerable additions —

the history of languages, their growth and decay, have been laid open to

dissection as never before, but the philosophy of language, the reason why

one man in some cases uses a different word to express the same idea as his

neighbour, and in other cases uses the same word, but sounds it so

differently that it is scarcely recognizable, the reason why the collocation

of ideas in the form of a sentence is so different in the mouths of one

nation compared with that of another, is still involved in obscurity.

For instance, what were the causes which induced the old Greeks long ages ago

to adopt v-d-r, the Saxons v-t-r, the Cymry d-v-r, as their base for water?

Why are the English so afraid of the guttural ch sound that they pronounce

night as nite, and Vaughan ( W= Vychan) as vawn? And why have the Cymry a

dislike to either the flat or sharp j sound, so that Johnny becomes ShOni,

while their brethren, the later Cornish adopted it and hir (long) became

cheer, a cliff now called the " Chair ladder " in reality yr hir

lethr. How is it that we say nothing but Edward for a man's name, but a

person speaking with a Strong "Welshy" accent utters a quite

appreciable approximation to the French Edouard, only with a sharp t sounded

at the end?

Comparative Philology has brought to light many important

|

|

|

CHAP. X.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 371

facts, it has taught us much of the relations of sounds, has traced obscure

relationships in the words themselves, and has classified diiferences under

the operation of laws, but it has a vanishing point. Just as biology under

the guidance and appliances of modern science can deal with the most abstruse

phenomena of life, but it can never fathom their well spring, so before the

student of philology as well as that of biology there is always a cm-tain

drawn, which he cannot lift; in other words he is still in the field of

secondary phenomena not in that of origins.

Applying this to the matter in hand, we may have a key to the great vitality

of the Welsh language, and shall be justified in at least being cautious

before endeavouring to compass its artificial extinction, assuredly the

time-honoured methods of the schools and colleges are artificial.

lEISH.

It is reported of Tiior the Scandinavian mythological hero, that he set out

fi'om Asgard'" for Joteuheim, the home of giants, the weird land of

frost and snow: in the course of his wanderings he arrived at Utgard, wliere

he was introduced into an immense banqueting hall; there around the table on

stone thrones were gravely seated giants who were determined on taking the

self-conceit out of him, and making light of his prowess, proposed that his

capacities should be tested. At one of the experiments whereby this was done,

he was handed a cup full of liquor which he was requested to empty; after

twice attempting to drain it by moderate draughts, Thor was surprised and

vexed to find that scarcely any impression was made on the surface; fiercely

applying himself a third time he just succeeded in reducing the liquor a

little below the rim.

Now a student entering on the study of Irish if he thinks to

* The home of the reputed gods.

|

|

|

|

|

|

372 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. X.

master it by the same means, and with no more trouble than he would pick up most

other European languages, would be very likely to share such feelings as the

Scandinavian folk attributed to Thor after his capacious draughts out of the

drinking cup, albeit, they apologize for him by saying, that the bottom of it

reached the ocean, and the ebbing and flowing of the tides are the visible

signs left of his mighty draughts.

The initial difficulty in Irish is caused by the great discrepancy between

the spelling and the pronunciation; I defy anyone to acquire an approximately

correct Irish pronunciation from such grammars as are at present published. A

mastery too of the constructions, and the use of the particles is by no means

child's play even to a person tolerably familiar with Welsh. Speaking of

difficulties, a friend of the author's may be mentioned, whose business took

him into every district in Ireland; being an intelligent man he wished to

acquire the language, but was obliged to desist from the attempt, and I have

heard him enunciate a theory that the superfluous consonants which constitute

a worse bugbsar than the initial mutations in Welsh, were inserted by the

Monks in order to keep the people in ignorance, this is ingenious, but

certainly unsupported by evidence.

We have already seen the disadvantages under which Welsh education has

laboured, on account of the exclusion of the language from the course of

elementary instruction. Up to within 1877 or thereabouts, the position of the

Irish language in the course of government education was almost precisely

similar to that of Welsh; there was however this important difference in the

status of the two languages; for many generations Irish had been going down;

it existed it is true, as a fireside tongue in the homes of the people,-but

it possessed no modern literature to speak of, and was rapidly becoming less

and less used.

There was it is true, and is now, a professor of Irish at

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. X.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 373

Dublin University, and perhaps a little might be read there of the extensive

Mediaeval literature of the past, but the persons up and down the country who

could read the language were but few and far between.

Under these circumstances a society was brought into existence, called the

"society for the preservation of the Irish language," the reader

should bear in mind that its promoters were not afraid of the word

preservation. This society held a congress in Dublin, in 1882, in which a

considerable number of facts were elicited, which helped to throw up in

relief the question of bilingual education in Welsh schools, in some matters

there is a striking parallel between Wales and Ireland, in others quite as

striking a contrast: I may also observe-that this society does not timidly

confine its aims to Irish-speaking children, but also that teaching the

language may be extended to English-speaking children in Ireland. What have

they done? They have sold 100,495 books,* among which are the first, second

and third Irish books giving elementary instructioii in that langiiage, and

6,225 copybooks, with headings in Irish. The following table shows the

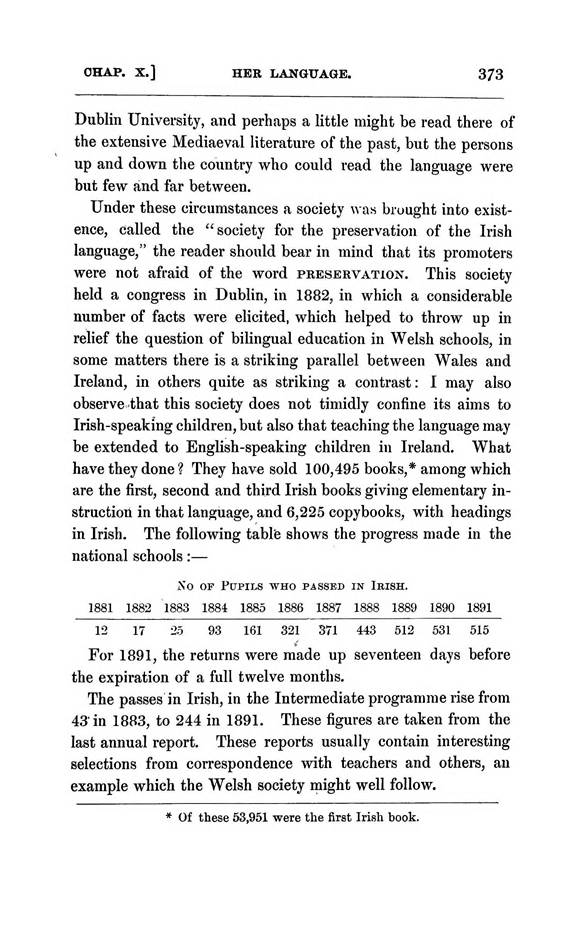

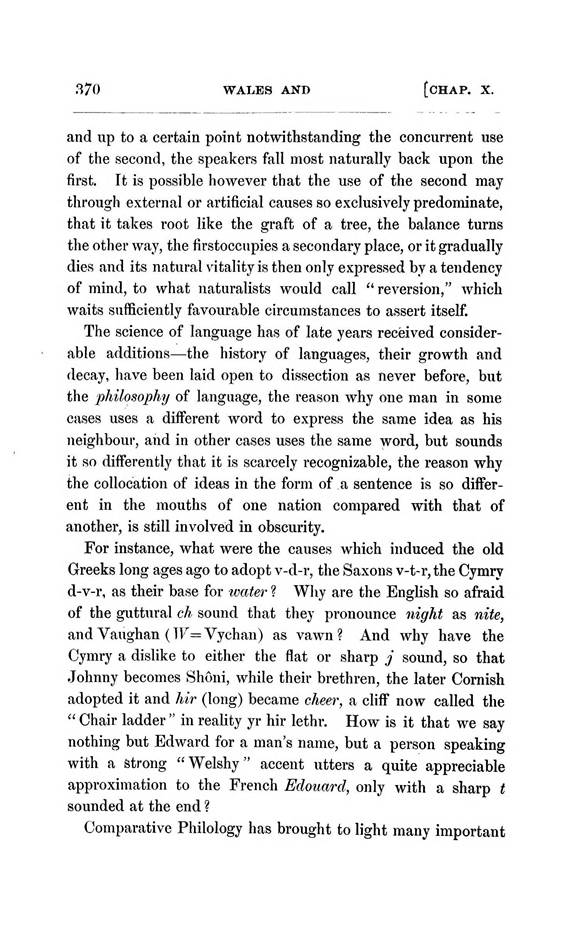

progress made in the national schools: —

No OP PcrPILS WHO PASSED IN IMSH. 1881 1882 1883 1884 1885 1886 1887 1888

1889 1890 1891 12 17 25 93 161 321 S71 443 512 531 515

i For 1891, the returns were made up seventeen days before

the expiration of a full twelve months.

The passes in Irish, in the Intermediate programme rise from43' in 1883, to

244 in 1891. These figures are taken from the

last annual report. These reports usually contain interesting

selections from correspondence with teachers and others, an

example which the Welsh society inight well follow.

* of these 53,951 were the first Irish book.

|

|

|

|

|

|

374 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. X.

Some of the reports from national school teachers, point to exactly the

difficulty with parents that has been experienced in Wales, e.g. Parents of

the boys disincline to allow their children to learn, in some instances are

found to have warned them against speaking Irish, or admitting that they

could, (Ennis); children regard the language ashamedly, encouraged to do so

by their parents (Sligo). The difficulty of securing qualified teachers has

also hampered the work of this society. The total number of persons speaking

Irish in 1881, in Ireland, was given by the census as 949,937, but in 1731

the Irish-speaking population was 1,340,808, in 1851 1,524,286; whether or no

the efforts of this society will ever lead to a recovery of the figures of

1851, we may not venture to say.

Since the end of last century, we see then, that the Welsh-speaking

population has increased, the Irish decreased.

At the 1882 meeting, Marcus J. Ward, of Belfast, said —

I value the national language, while it lives, because it is the key which

alone can furnish a means of knowing completely the Celtic genius of our

countrymen. It is the only way to the hearts and minds of our Irish-speaking

population, in whom we may trace unerringly what are the characteristics, the

bent, and the tendency of the nationality to which we belong, and on what

stock have been grafted the successive immigrations to this our land.

A very singular monument to the religious zeal of the ancient Irish, before

the fangs of popery were fully closed on the Island is to be found at this

day in Vienna, in Die Schottische strasse, the Irishmen's street, so-called

from its connection with the Scoto-Irish missionaries of the early middle

ages. These very missionaries left manuscript remains to which it may be said

we are indebted for that monument of German industry and difficult research,

the " Grammatica Celtica " of I. C. Zeuss, which has been for

several years the chief authority among scholars on Celtic grammar.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. X.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 375

Although Irish Gaelic possesses scarcely any modern literature in the usual

acceptation of the term, the Scotch Gaelic is rather differently situated.

Mary Macpherson, a professional nurse, seventy years old, is a recent

poetess, whose works have attracted some attention, yet strange to say, she

can read, but cannot write her own compositions, of which a volume containing

between eight and nine thousand lines taken down from her own recitation, was

published at Inverness, in 1891, for five shillings.

The Gaelic speaking population of Scotland, is about 400,000 that of the Isle

of Man, whose dialect by the way, appears far easier to master than Irish, my

own small experience may be trusted, perhaps does not exceed a few score.

|

|

|

|

![]() Statistics for

Welsh Texts Section / Ystadegau’r Adran Destunau Cymraeg

Statistics for

Welsh Texts Section / Ystadegau’r Adran Destunau Cymraeg