...

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6883) (tudalen clawr)

|

AN

INTRODUCTION

TO

EARLY WELSH

BY

THE LATE JOHN STRACHAN, LL.D.,

Professor of Greek and Lecturer in Celtic in the University of Manchester

MANCHESTER

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1909

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6883b) (tudalen 00_i)

|

PUBLICATIONS

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER

CELTIC

SERIES No. I.

An

Introduction to Early Welsh

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6884) (tudalen 00_ii)

|

SHERRATT & HUGHES

Publishers to the Victoria University of Manchester Manchester: 34 Cross

Street London: 33 Soho Square W.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6885) (tudalen 00_iii)

|

AN

INTRODUCTION

TO

EARLY WELSH

BY

THE LATE JOHN STRACHAN, LL.D.,

Professor of Greek and Lecturer in Celtic in the University of Manchester

MANCHESTER

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1909

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6886) (tudalen 00_iv)

|

UNIVERSITY

OF MANCHESTER PUBLICATIONS No. XL.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6887) (tudalen 00_v)

|

PREFACE

THIS book is the outcome of the courses of lectures on Welsh grammar and

literature given by the late Pro- fessor Strachan at the University of

Manchester during the sessions 1905-6 and 1906-7. Indeed, the Grammar is in

the main an expansion of notes made for these lectures. For the numerous

quotations from early Welsh literature contained in the Grammar, as well as

for the Reader, Strachan made use not only of published texts, notably those

edited by Sir John Rhys and Dr. J. Gwenogvryn Evans, but also of photographs

specially taken for the purpose, and of advance proofs of the edition of the

White Book and of the photographic facsimile of the Black Book of Chirk,

about to be published by Dr. Evans, both of which were lent by him to

Strachan. The Reader includes Middle Welsh Texts selected as likely to be of

most value for illustration or of special interest. The very valuable work

done by Dr. Evans in relation to these texts was of the greatest assistance

to Professor Strachan, and as an expression of gratitude for the help thus

given, as well as in recognition of the services rendered to Welsh

scholarship by Dr. Evans, it was the intention of the author to dedicate his

book to him. The idea of working up his notes into a book that might serve as

an introduction to the study of older Welsh seems first to have occurred to

Strachan in the spring of 1907. On the fifth of April he wrote to Mr. R. I.

Best, the Secretary of the School of Irish Learning in Dublin: " I have

been thinking of drawing up a little primer of Early Welsh. With that the

language of Middle- Welsh prose should be child's play

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6888) (tudalen 00_vi)

|

vi

PREFACE

to learn. However, that may or may not come off." And to his old friend

Dr. P. Giles of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, he wrote on the same day: "

I think I must draw up and print outlines of Middle- Welsh grammar. I cannot

well teach without some book, and the beginner is lost in the wilderness of

the Grammatica Celtica." His original intention evidently was to publish

a mere sketch of the grammar, somewhat like his Old-Irish Paradigms. But at

the suggestion of his friend and colleague, Professor T. F. Tout, he decided

to expand the Grammar on the larger and fuller lines of the present volume.

At the same time the plan of adding a Reader of excerpts from mediaeval Welsh

literature took concrete shape in the course of conversations and

correspondence with Dr. Evans. On both these tasks he began to work during

the Summer Term of 1907. With what amazing rapidity he must have toiled to

have all but completed the work by the end of the following August! Giving up

a visit to Germany to which he had long been looking forward, he devoted the

whole long vacation to the preparation and printing of his book. At the

moment of his death, on the 25th of September, both the Grammar and Reader

were in type, and he had read a first, and in some cases a second, proof.

Writing to Professor Thurneysen a week before his death, he says that he had

then only the notes and vocabulary to add.

After Professor Strachan's death, at the request of the Publications

Committee of the Manchester University, Professor Kuno Meyer of the

University of Liverpool kindly undertook the task of reading final proofs of

the Grammar and Reader, and of adding a Glossary, an Index and a list of contents.

In this task, which involved very considerable labour, he obtained the

assistance of Mr. Timothy Lewis, who had worked for two years under Professor

Strachan, and who returned

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6889) (tudalen 00_vii)

|

PREFACE

vii

from Berlin whither he had gone to continue his studies with Professor

Zimmer, and devoted the winter to help with the completion of the book. Mr.

Lewis verified the quotations in the Grammar where this was possible; drew up

the Glossary, prepared the Index, and revised proofs. An old student of

Professor Meyer's, the Rev. Owen Eilian Owen, placed his collection of Old

and Middle- Welsh words at his disposal for the elucidation of rare and

difficult vocables, while both Mr. Owen and Mr. J. Glyn Davies read proofs of

the whole book, many valuable suggestions being due to them. But Professor

Meyer and Mr. Lewis are solely responsible for the Glossary.

There can be no doubt that if Strachan had lived to complete the book

himself, he would have made alterations and additions in several places both

in the Grammar and Reader, and would have still further normalised the

spelling in his critical versions of sections IV. and V. in the Reader. It

will be observed that his treatment of the texts varies greatly. Except in

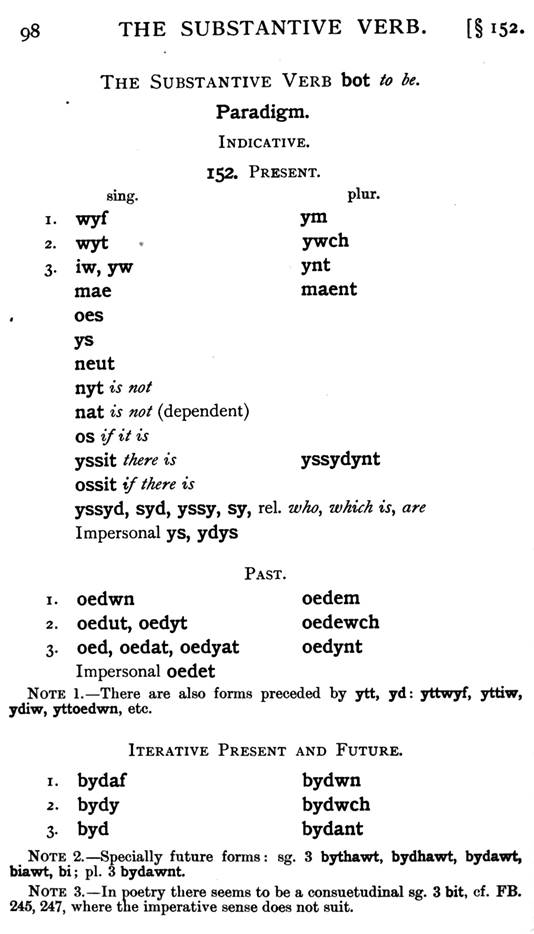

the sections just mentioned, he does not seem to have aimed so much at the

construction of a critical text as at the presentation of a clear, precise,

and intelligible version, which would at the same time serve to introduce the

student to the characteristic features of Middle Welsh orthography. In the

Corrigenda some necessary emendations 1 have been indicated by Professor

Meyer

1. From a collation of the poems printed from the Red Book with the original,

it appears that the following corrections should be made:

P. 233, 1. 4, for dOg read dOwg

ib., 1. 19, for aghaeat read agkaeat P. 235, 1. 29. for gOawr raidgOaOr P.

236, 1. 2, for can read kan P. 237, 1. 22, for uvulldaOt read uvulltaOt P. 238,

1. 9, for dyrnaOt read dyrnnaOt

ib,, 1. 11, for diffirth read diffyrth

ib., 1. 18, for vedissyawt read vedyssyaOt

ib. , 1. 20, for adueil read atueil

Vlll

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6890) (tudalen 00_viii)

|

PREFACE

who has also added some further variants (marked a, b, &c.) in the

foot-notes.

Strachan had left behind no material for the Glossary except a first rough

list of words. In drawing it up use was made of a letter to Thurneysen, in

which he expressed his intention to arrange the words according to their

actual sounds. His only doubts were about the phonetic value of final c, t,

p. On this point he wrote: " Of course final b is common, also certain

of my texts write d for d. But none of them have g for final g." In

accordance with modern pronunciation, Professor Meyer considered it desirable

to substitute the letter g, though the period at which final c became voiced

has not yet been established.

No notes to the texts were found among Strachan 's papers. He had brought

back from Peniarth, from MSS. No. 22, 44, 45, and 46, a large number of

variants to the Story of Lear and that of Arthur, which he would no doubt

have used for his notes. Those to Lear have been printed in an Appendix; but

the Peniarth versions of Arthur seem to differ so much from those of the Red

Book and the Additional MS. 19,709 that they would have to be printed in

full.

Since the great work of Zeuss, this is the first attempt to write a grammar

of Early Welsh on historical principles. It was the hope of the author

expressed in letters to friends that his work would stir up Welsh scholars to

investigate more thoroughly than they have done hitherto the history of their

language. But no one was more conscious of the gaps still left by his work

than Strachan himself. " It is only a beginning," he wrote to

Thurneysen. " I hope people will make some allowance for the

difficulties of the work and the scanty amount of trustworthy material. One

is continually finding out something new." References to the need of

further investigation will be found in many places throughout the Grammar.

His own discoveries

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6891) (tudalen 00_ix)

|

PREFACE

ix

of the functions of ry, of the relative forms of the verb, and his account of

the uses of the verbal prefixes a and y3 point out the way to future

investigators in this neglected field of research. To these discoveries he

was led by his unrivalled knowledge of Irish grammar, so intimately connected

in its origins with that of Welsh that he believed no true progress possible

without their parallel study. " It is absurd to think," he once

wrote to Mr. Best, " that either branch of Celtic can be satisfactorily

studied apart from the other;" and to Mr. Giles: "Without the

knowledge of Irish early Welsh grammar is rather like a book sealed with

seven seals."

The circumstances under which this book has been produced having been thus

indicated, it remains to express acknowledgement of the work of the scholars

who have contributed towards the result: first to those whose assistance to

Professor Strachan in his lifetime he would specially have desired to

recognise; in particular to Dr. Evans who furnished the editions both

published and unpublished of the Welsh texts which were used in compiling the

Reader; to the late Mr. Wynne of Peniarth who freely gave access to the MSS.

in his possession; and to Sir John Rhys (joint editor of the Red Book and of

other texts) and to the Fellows of Jesus College, Oxford, who afforded every

facility in their power; secondly to those who since the author's death have

enabled his work to be presented to the public, especially to Professor Tout

who initiated the idea of preparing the book for publication and undertook

the arrangements for it; to Professor Kuno Meyer, whose long and intimate

association with Strachan in his Celtic studies specially fitted him to

undertake the duty of revising the whole work and seeing it through the

press; to Mr. Lewis in assisting Professor Meyer particularly in the

preparation

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6891b) (tudalen 00_x)

|

PREFACE

of the Glossary; and to Mr. O. Eilian Owen and Mr. J. Glyn Davies for their help in reading proofs. The title of the book was chosen by Strachan himself.

It has been the earnest wish of those who have taken part in preparing this work for publication that it should appear in a form worthy of the reputation and memory of the distinguished scholar whose career was cut short so sadly in the midst of his full literary activity, and that the results of his devoted labours and profound learning should not be lost to students of the Welsh language.

February, 1909.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6891c) (tudalen 00_xi)

|

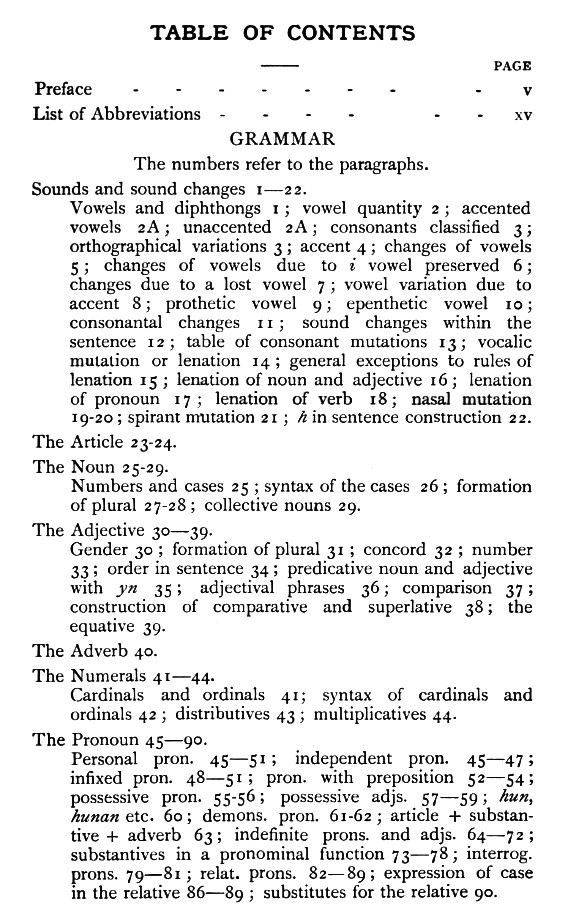

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface

List of Abbreviations

GRAMMAR

The numbers refer to the paragraphs.

Sounds and sound changes 1—22.

PAGE

Vowels and diphthongs ; vowel quantity 2 ; accented

vowels 2A ; unaccented 2A; consonants classified 3 ;

orthographical variations 3 ; accent 4 ; changes of

vowels

5 ; changes of vowels due to i vowel preserved 6 ;

changes due to a lost vowel 7 ; vowel variation due

to

accent S ; prothetic vowel 9 ; epenthetic vowel 10 ;

consonantal changes 1 r •

sound changes within the

sentence 12 ; table of consonant mutations 13 ;

vocalic

mutation or lenation 14 ; general exceptions to

rules of

lenation 15 ; lenation of noun and adjective 16 ;

lenation

of pronoun 17 ; lenation of verb 18; nasal mutation

19-20 ; spirant mutation 21 ; h in sentence

construction 22.

The Article 23-24.

The Noun 25-29.

Numbers and cases 25 ; syntax of the cases 26 ;

formation

of plural 27-28; collective nouns 29.

The Adjective 30—39.

Gender 30 ; formation of plural 31 ; concord 32 ;

number

33 ; order in sentence 34 ; predicative noun and

adjective

with yn 35 ; adjectival phrases 36; companson 37 ;

construction of comparative and superlative 38; the

equauve 39.

The Adverb 40.

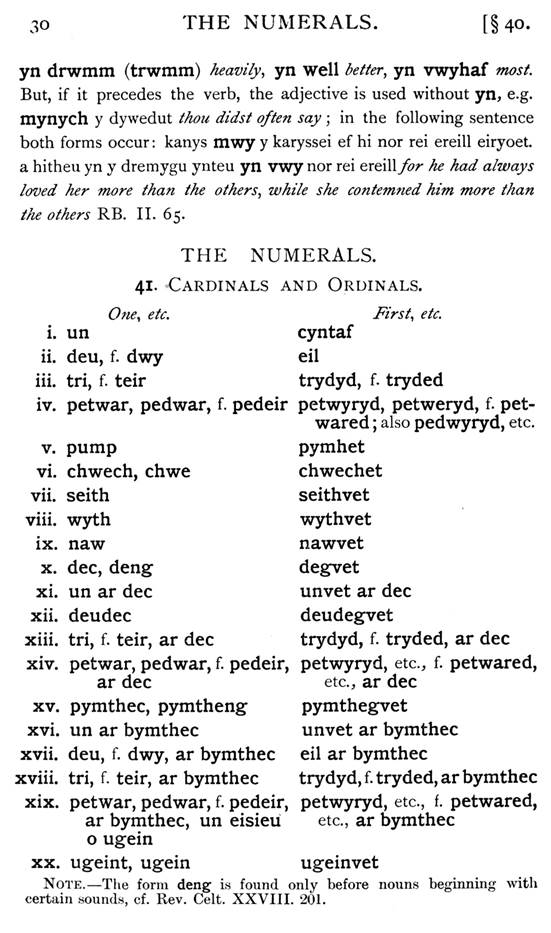

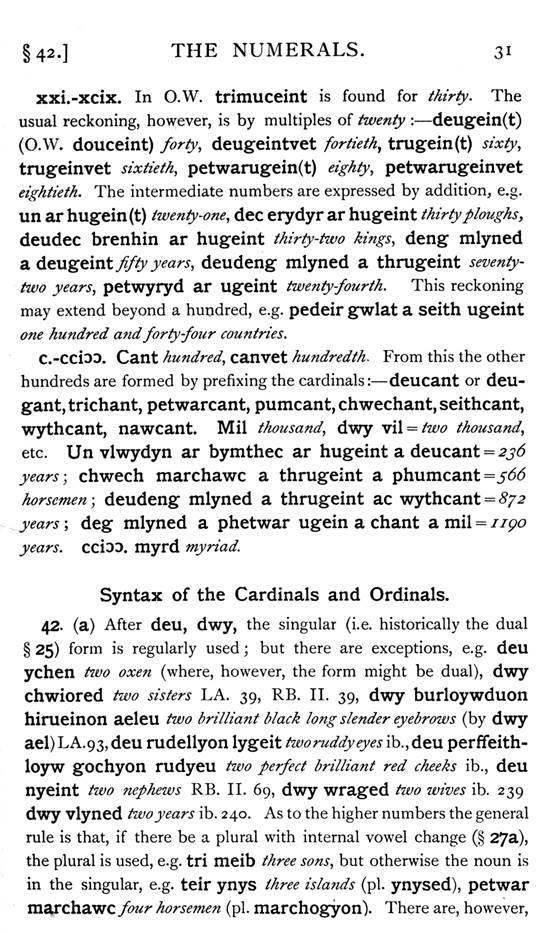

The Numerals 41—44.

Cardinals and ordinals ;

syntax of cardinals and

ordinals 42 ; distributives 43 ; multiplicatives 44.

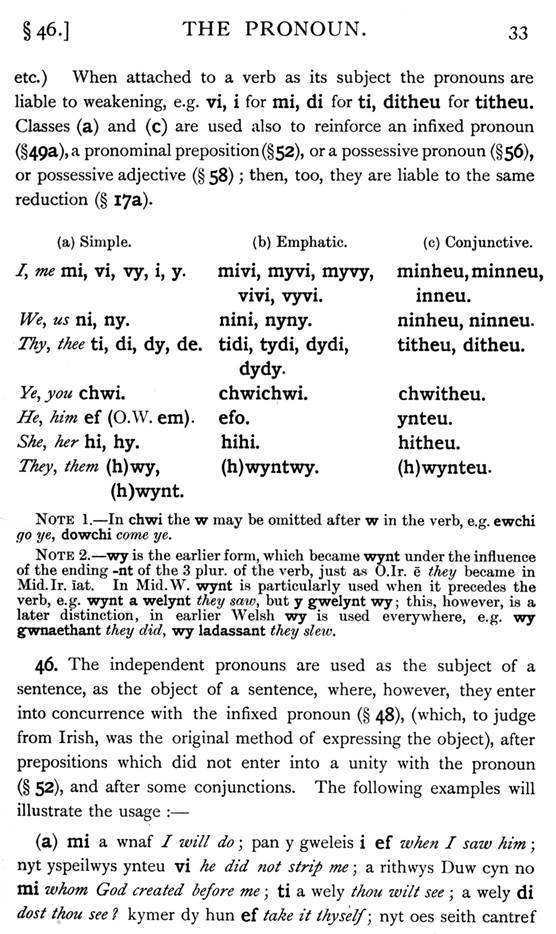

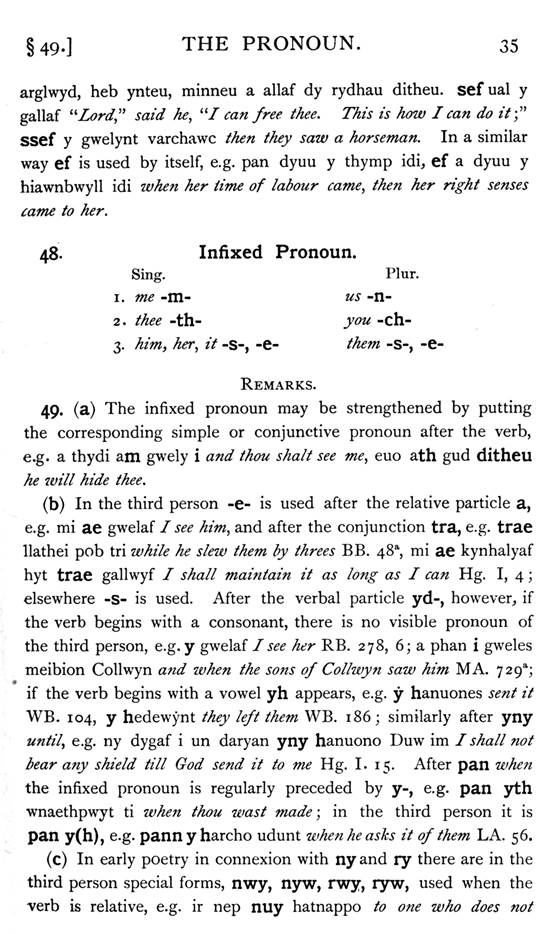

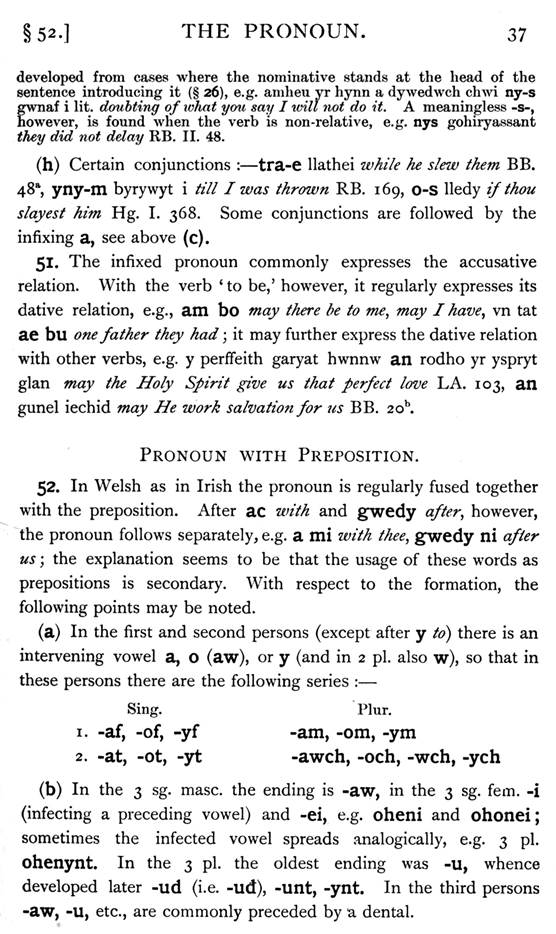

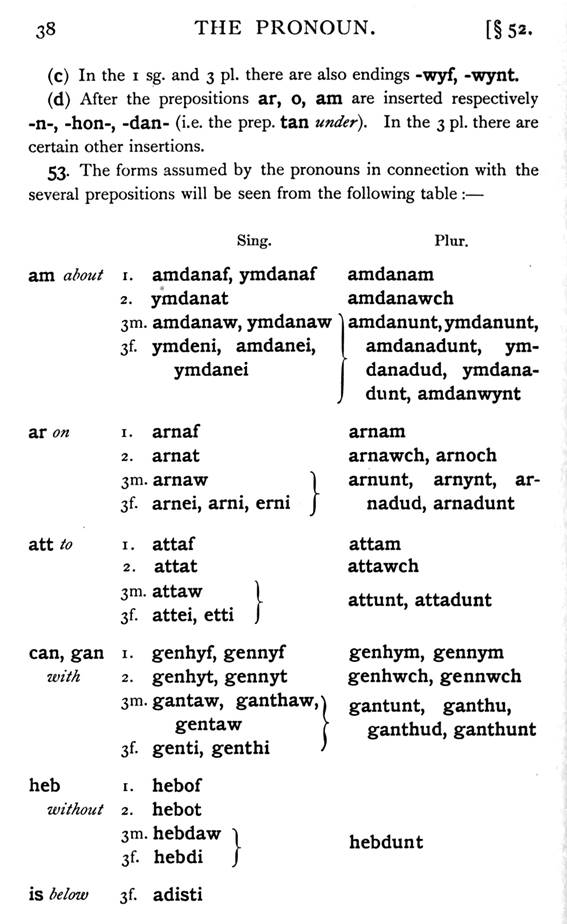

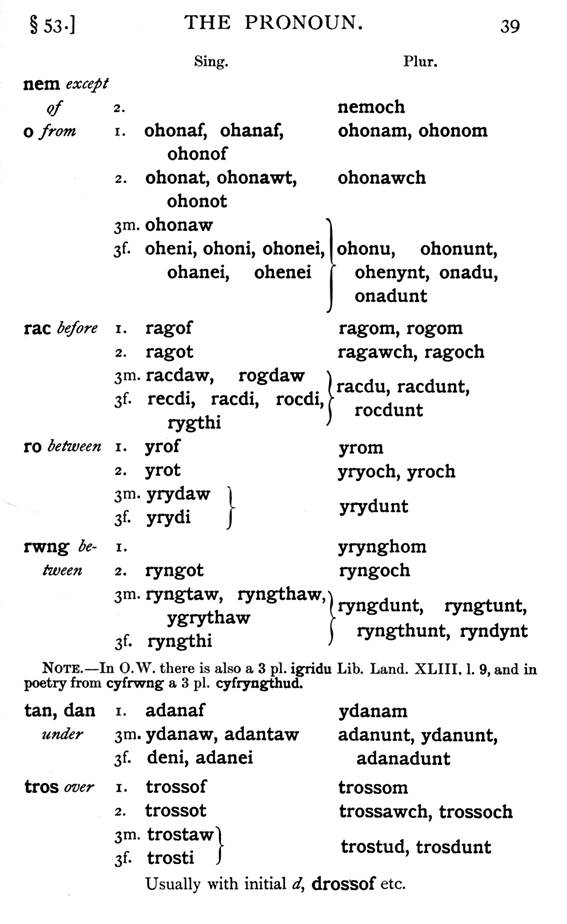

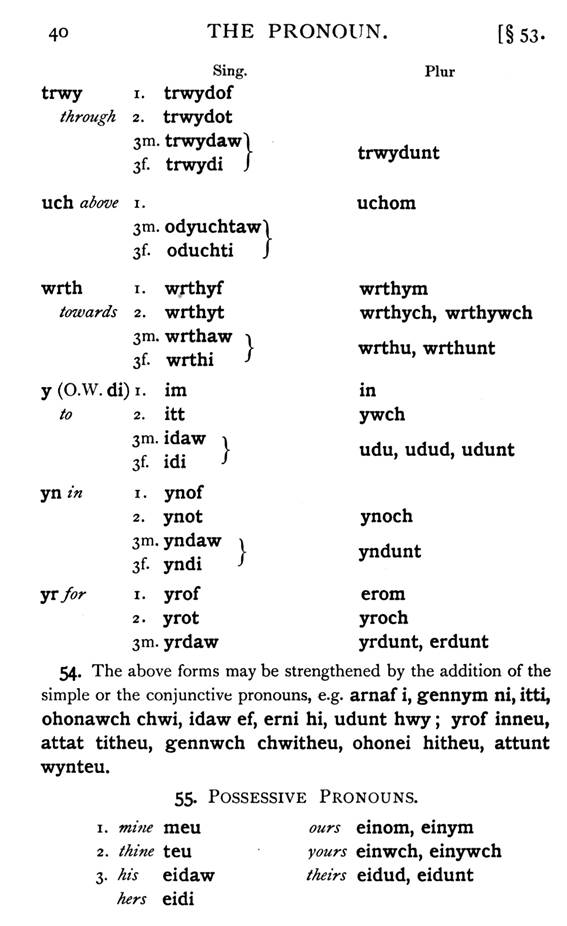

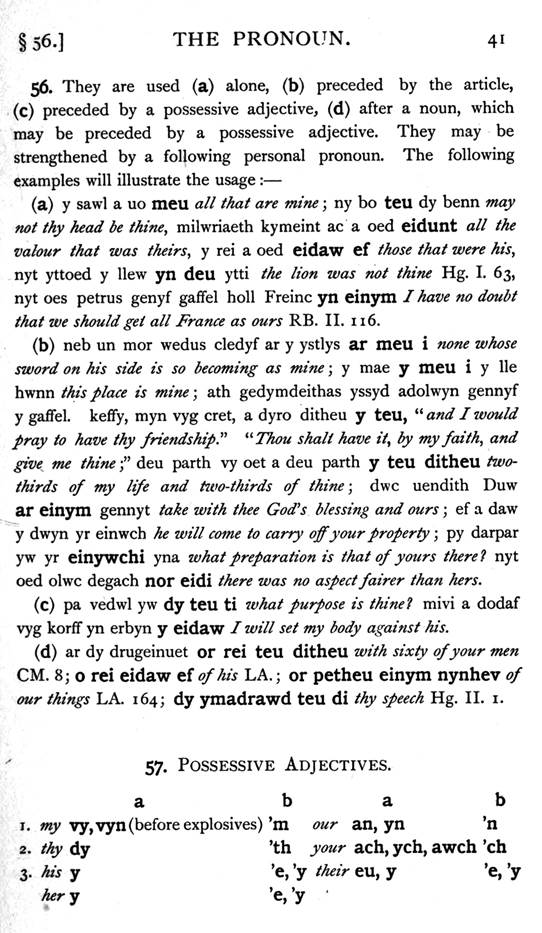

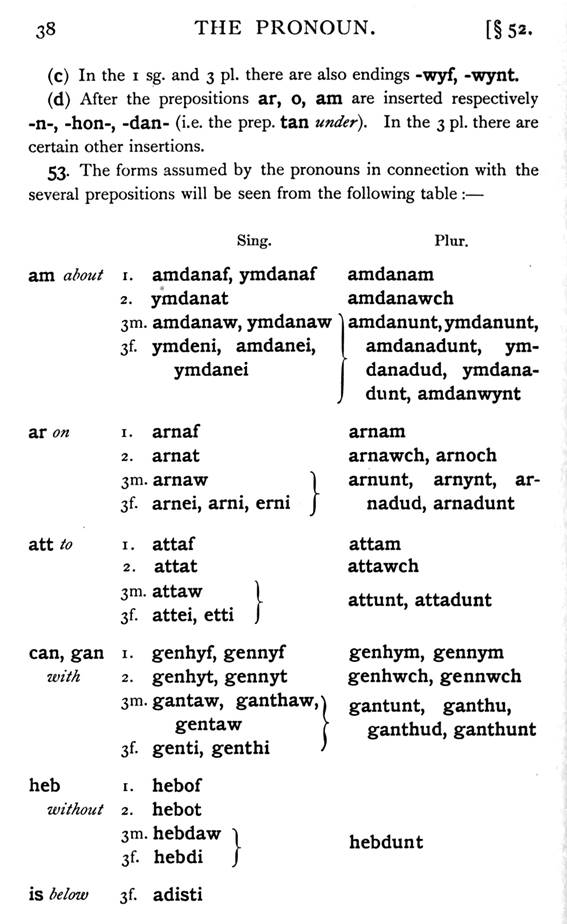

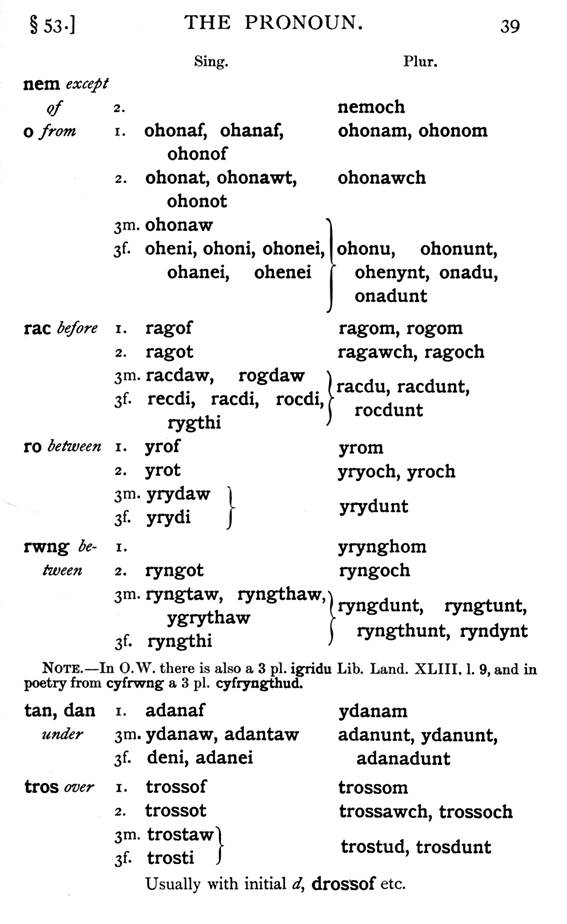

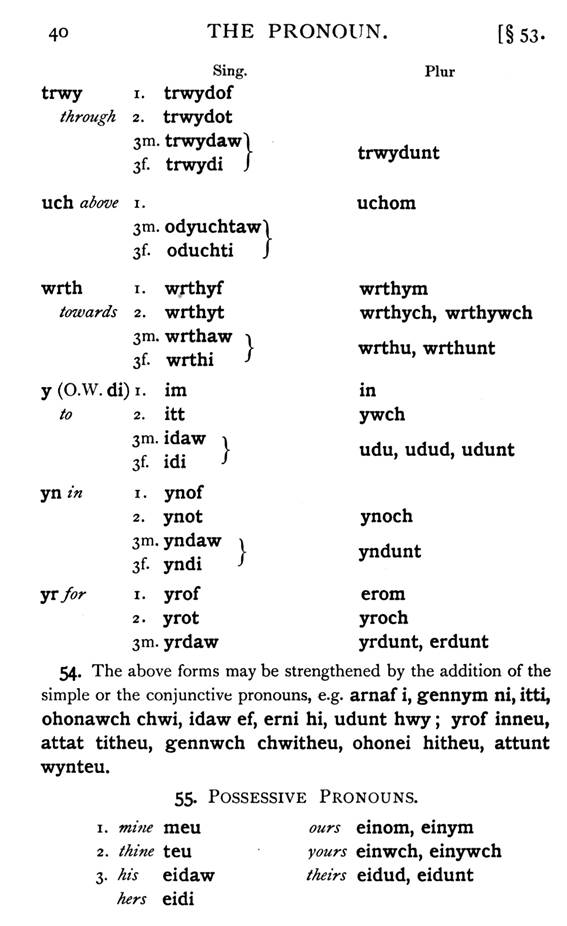

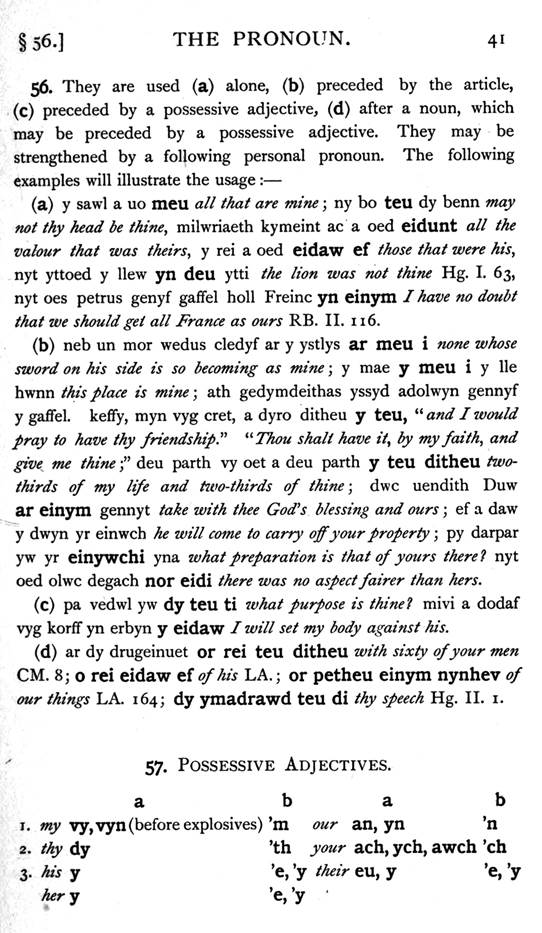

The Pronoun 45—90.

independent pron. 45—47 ;

Personal pron. 45—51 ;

infixed pron. 48—51 ; pron. with preposition 52—54 ;

possessive pron. 55-56; possessive adjs. 57—59 ;

kun,

hunan etc. 60 ; demons. pron. 61-62 ; article +

substan-

tive + adverb 63 ; indefinite prons. and adjs. 64—72

;

substantives in a pronominal function 7 3—78 ;

interrog.

prons. 79—81 ; relat. prons. 82— 89 ; expression Of

case

in the relative 86—89 ; substitutes for the relative

90.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6892) (tudalen 00_xii)

|

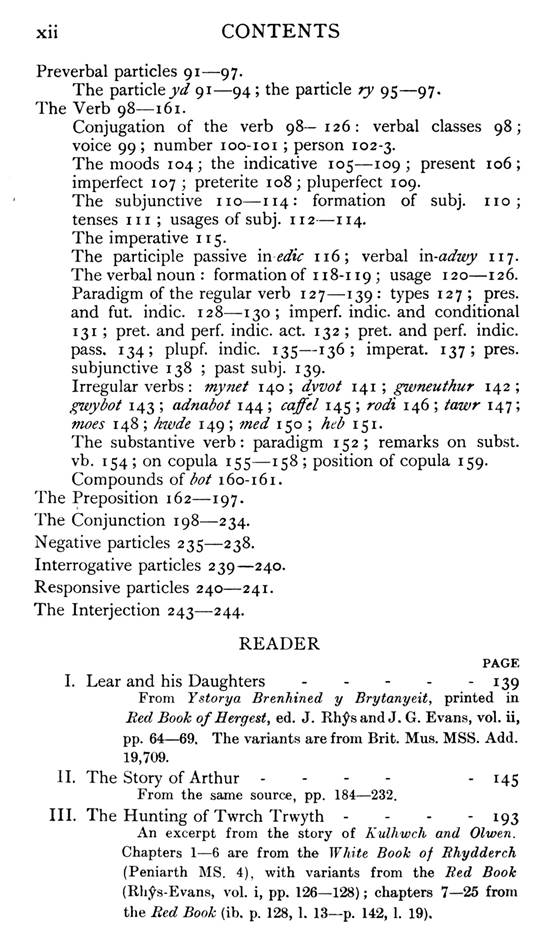

xii CONTENTS

Pre verbal particles 91 97.

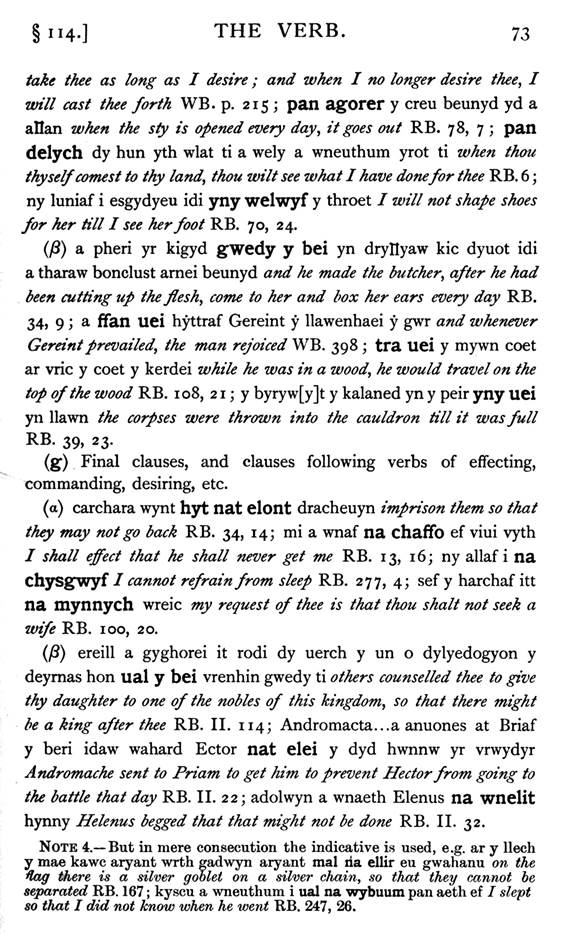

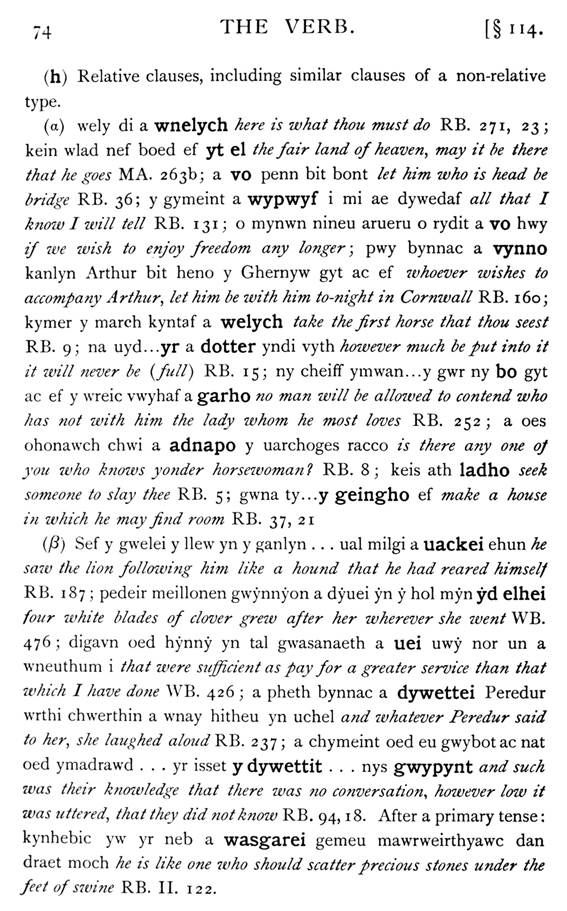

The particle yd 91 94; the particle ry 95 97. The Verb 98161.

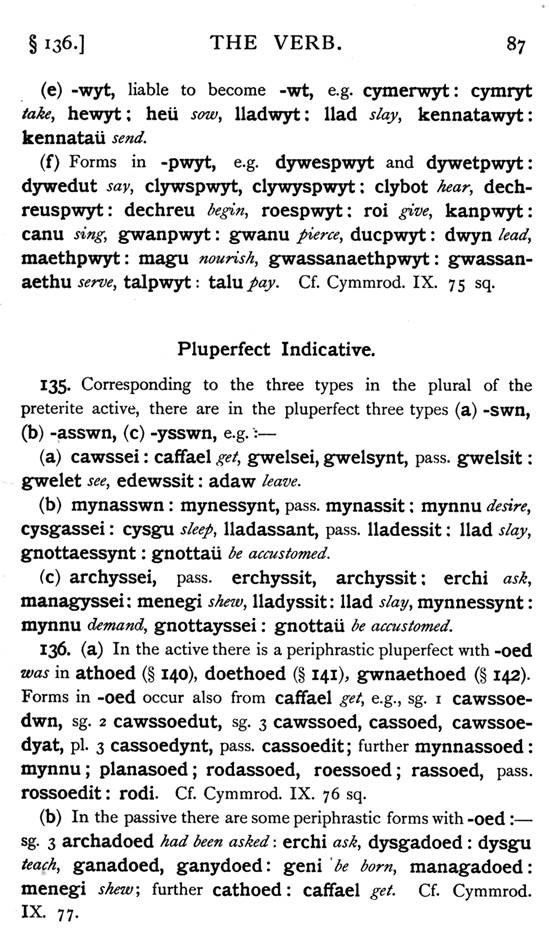

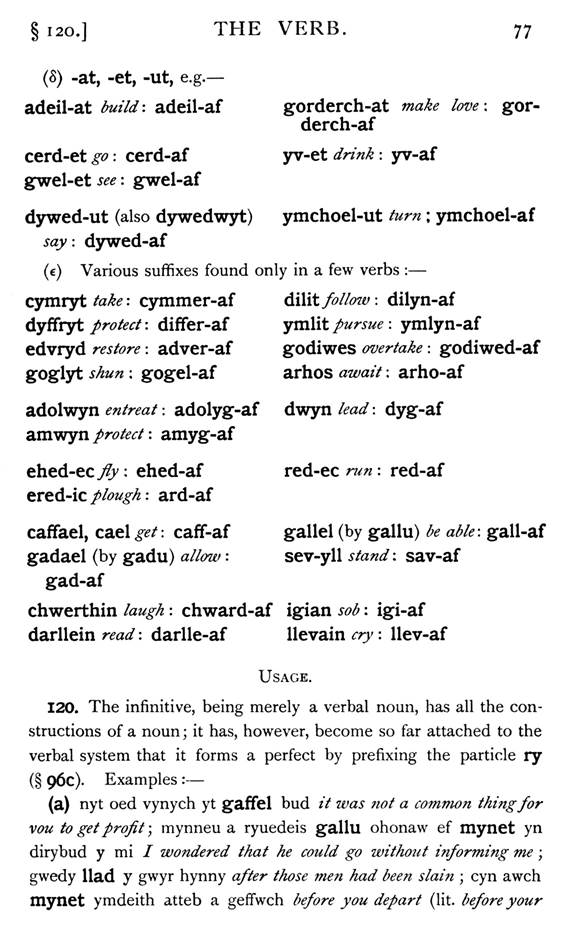

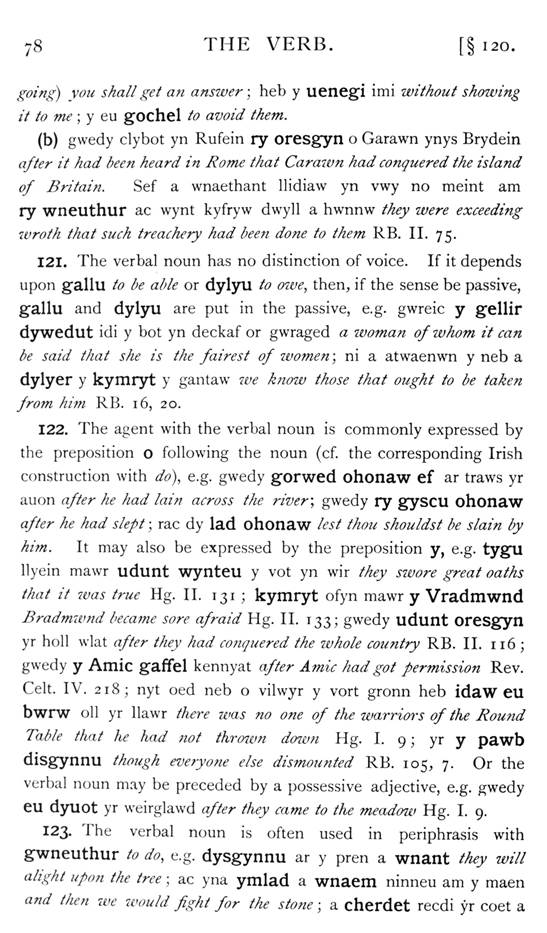

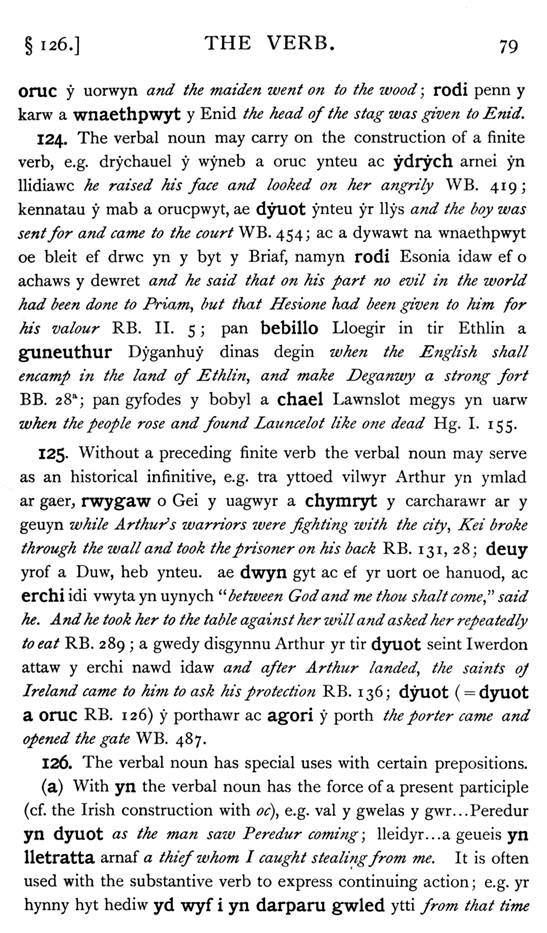

Conjugation of the verb 98126: verbal classes 98;

voice 99; number 100-101; person 102-3.

The moods 104; the indicative 105 109; present 106;

imperfect 107; preterite 108; pluperfect 109.

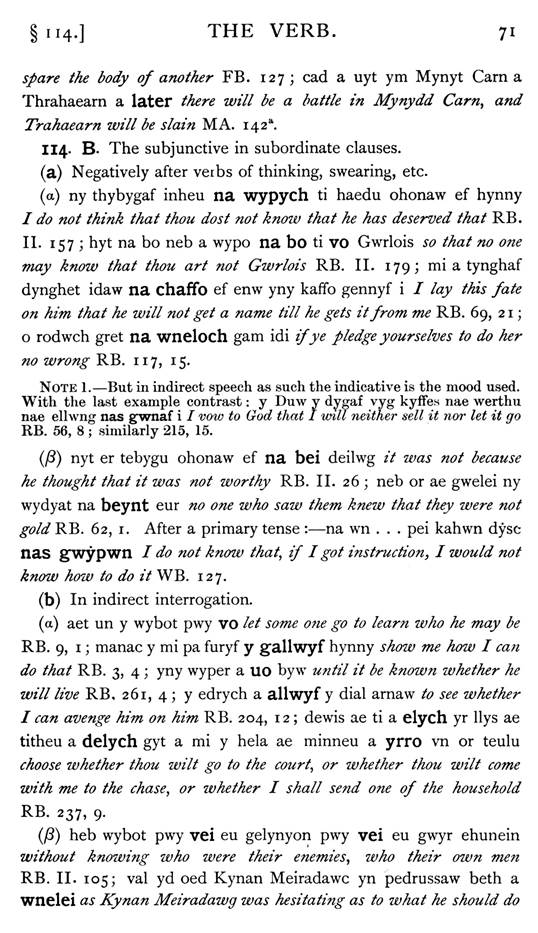

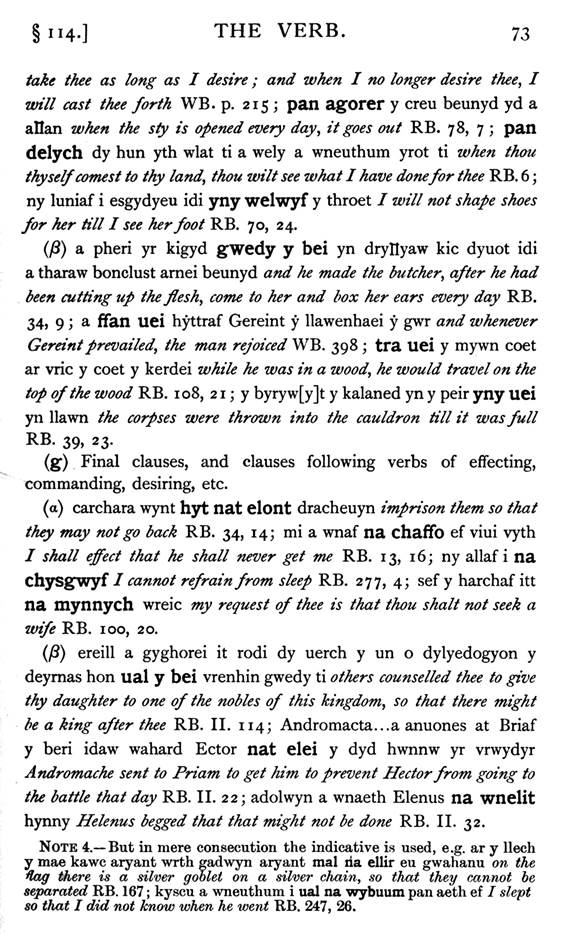

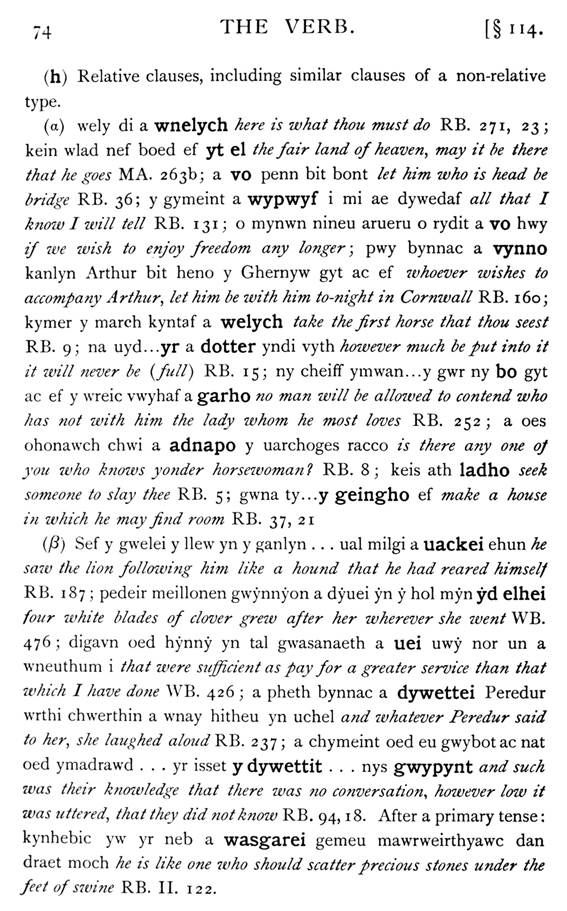

The subjunctive no 114: formation of subj. no;

tenses in; usages of subj. 112 114.

The imperative 115.

The participle passive medic 116; verbal \x\-adwy 117.

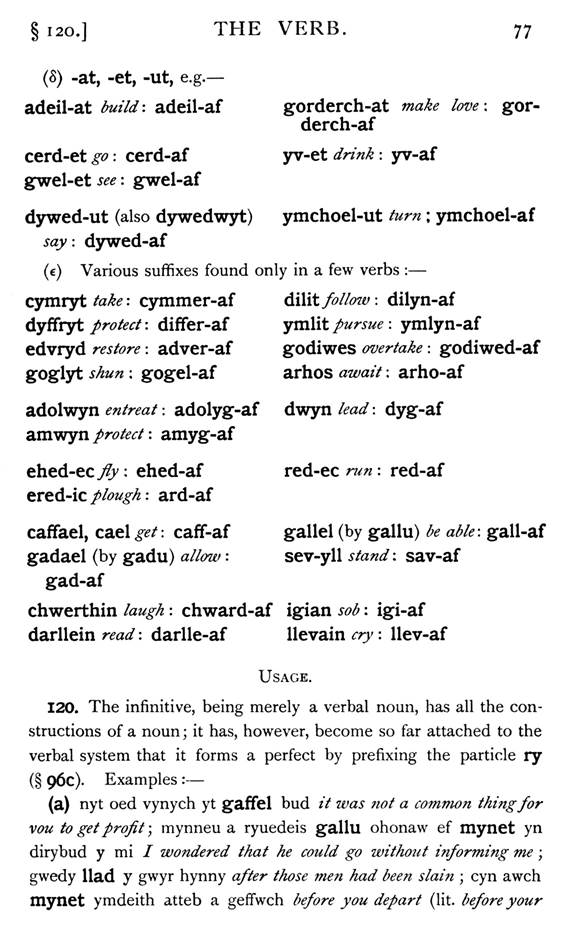

The verbal noun: for mation of 118-119; usage 120 126.

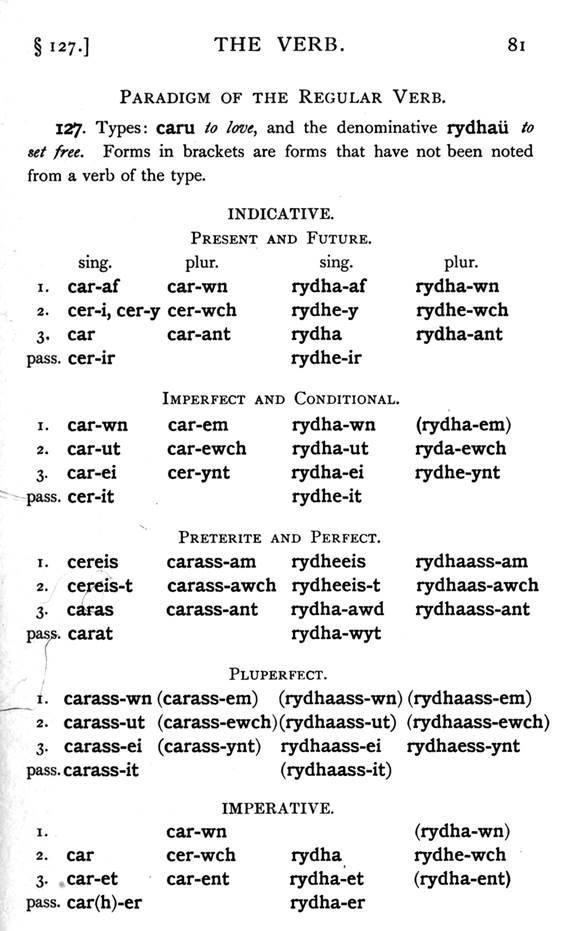

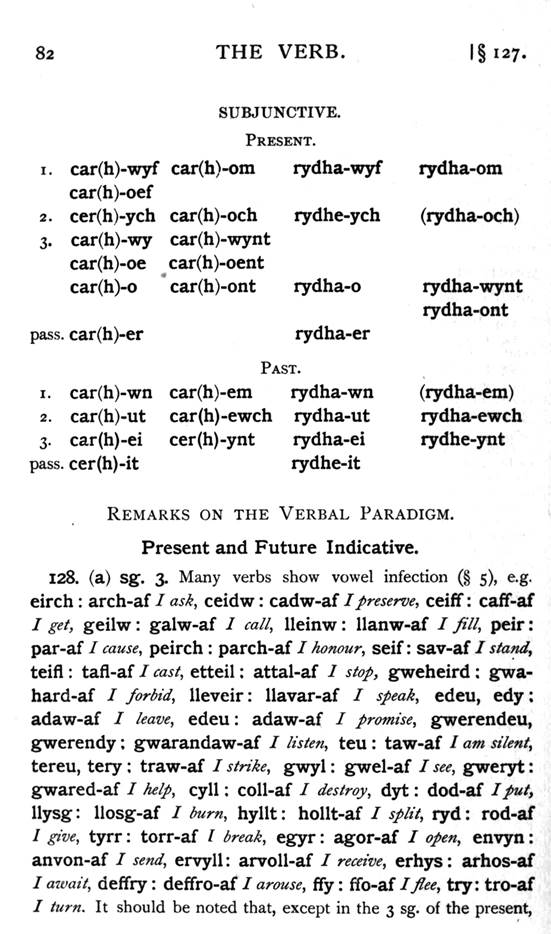

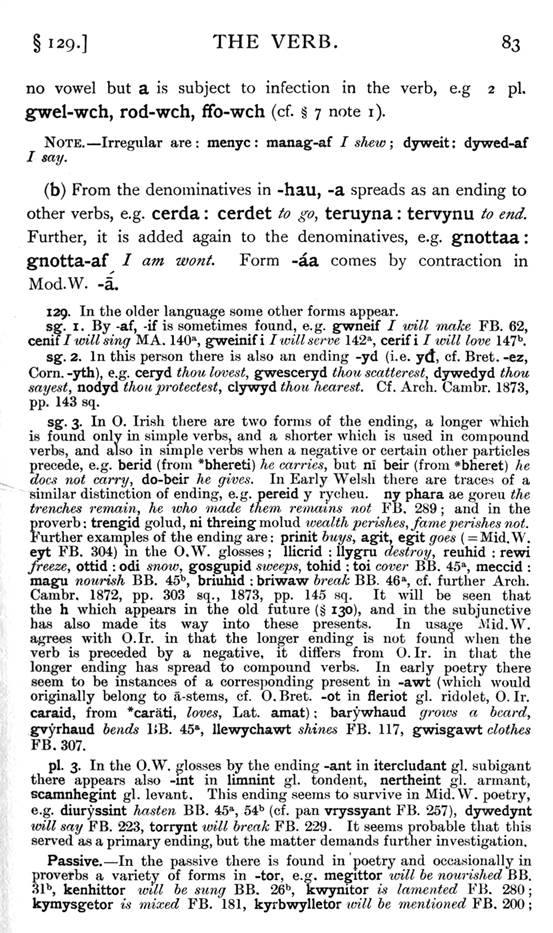

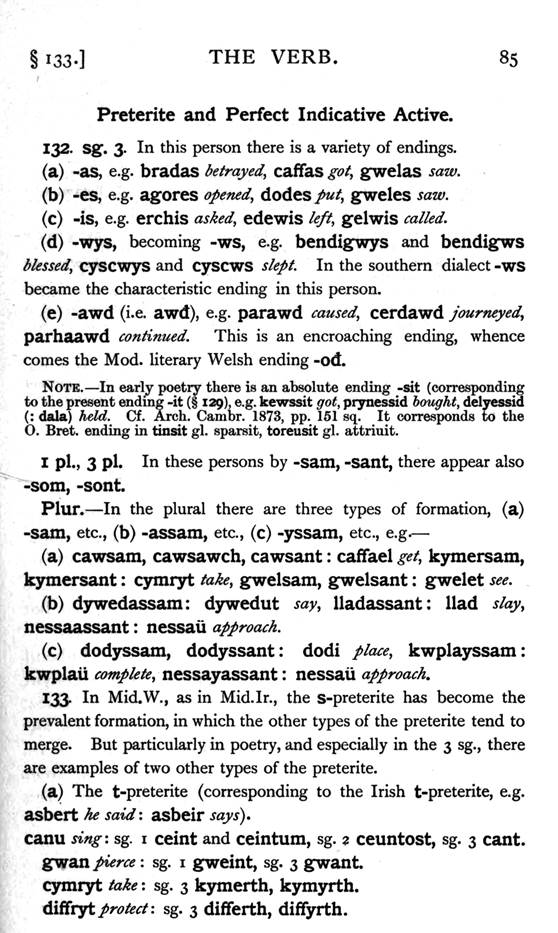

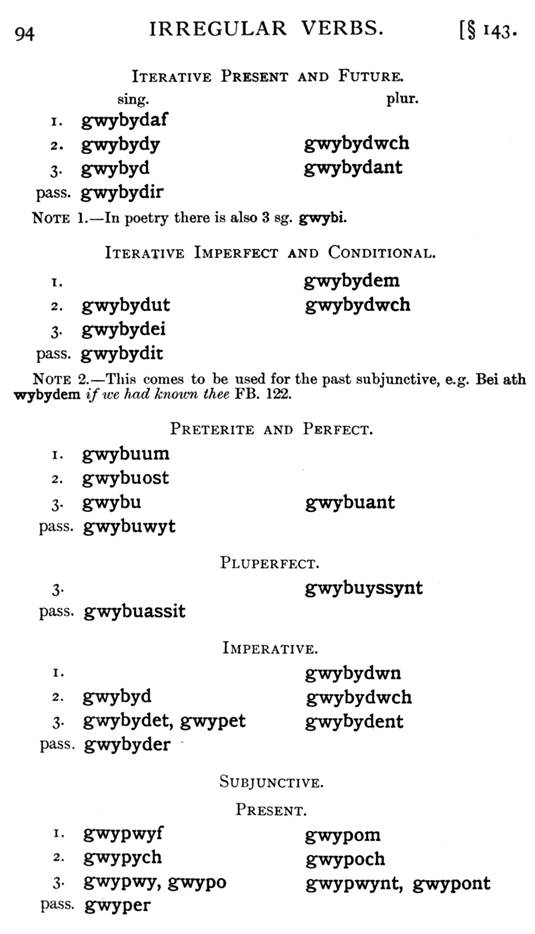

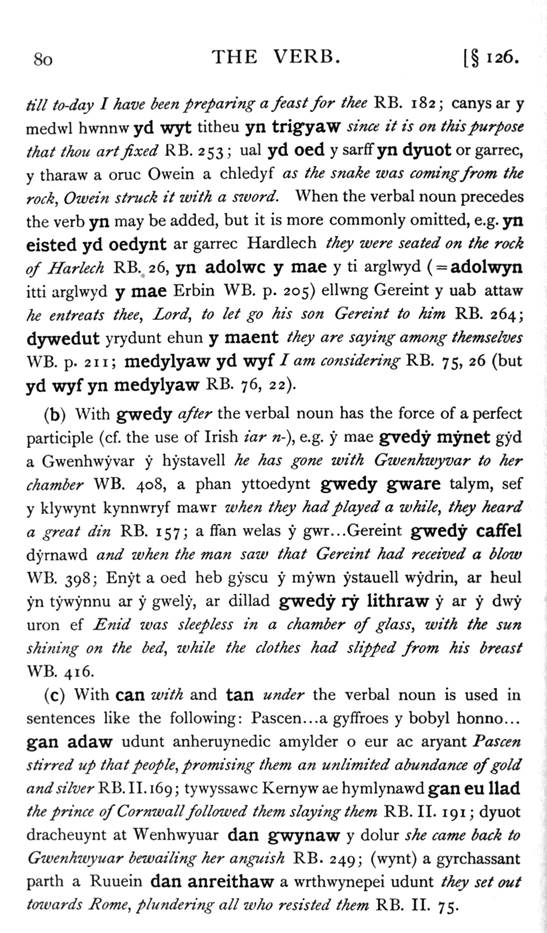

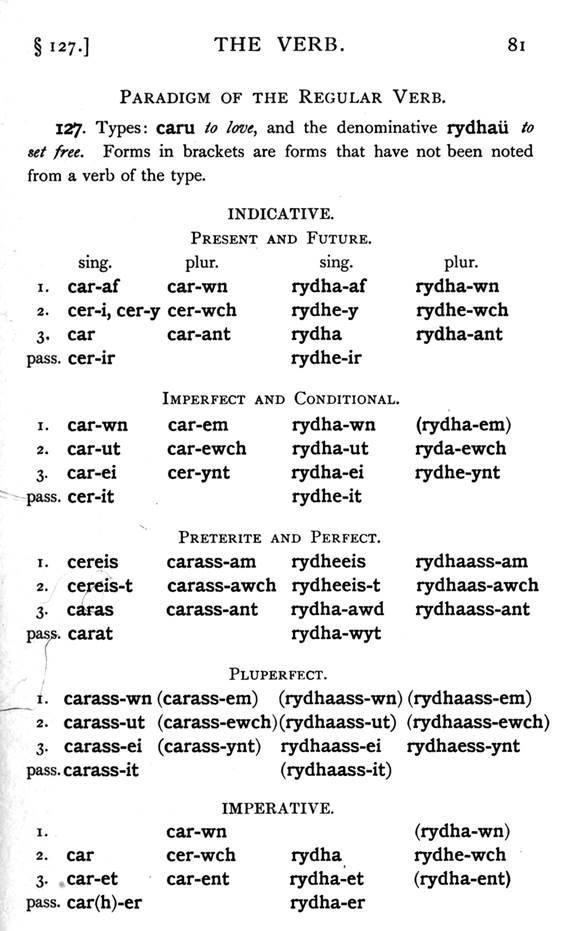

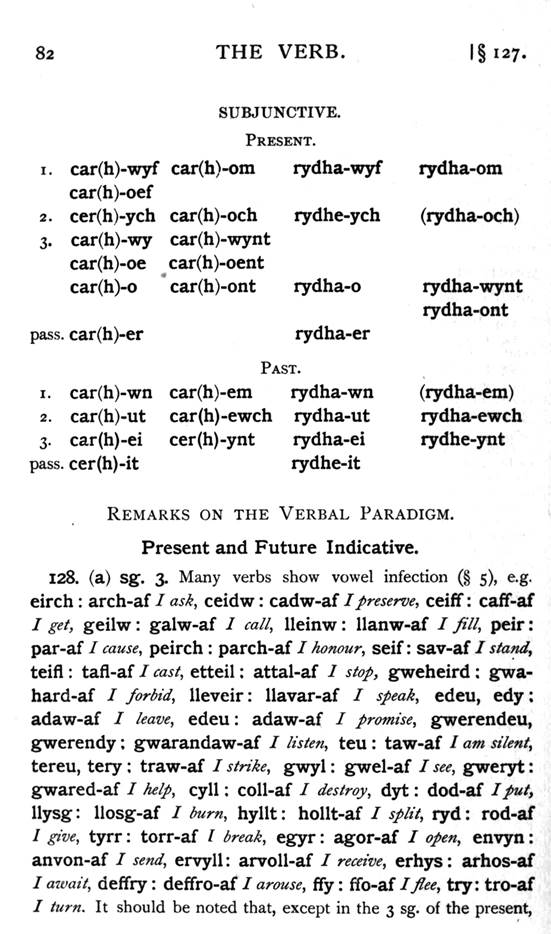

Paradigm of the regular verb 127 139: types 127; pres.

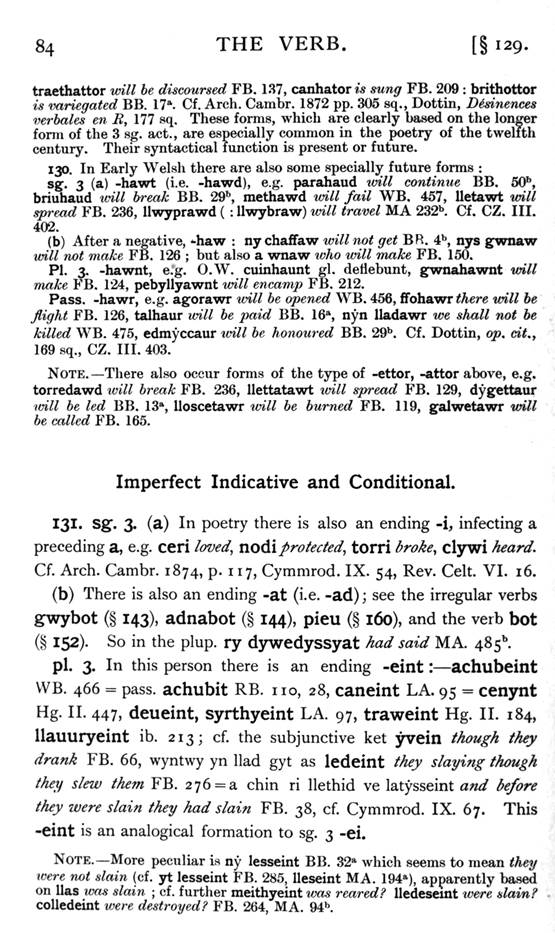

and fut. indie. 128 130; imperf. indie, and conditional

131; pret. and perf. indie, act. 132; pret. and perf. indie.

pass. 134; plupf. indie. 135 136; imperat. 137; pres.

subjunctive 138; past subj. 139.

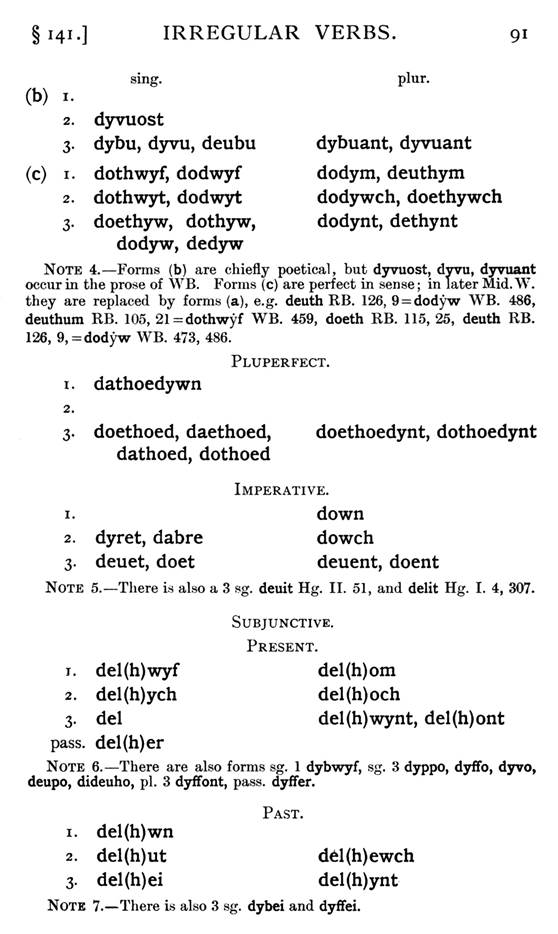

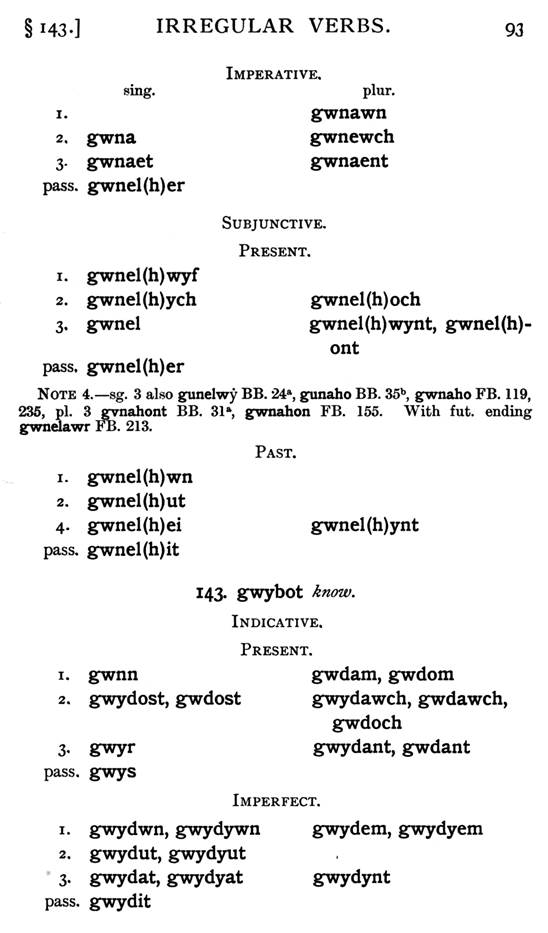

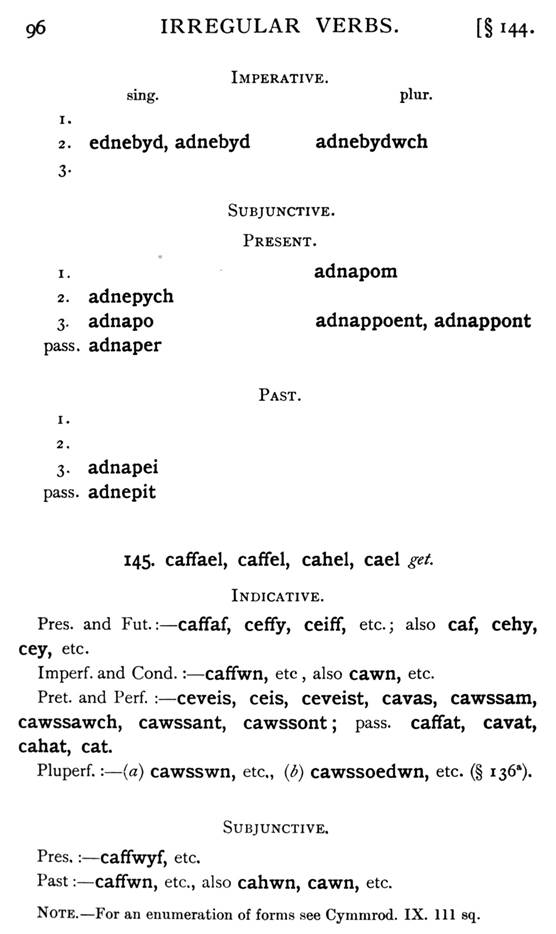

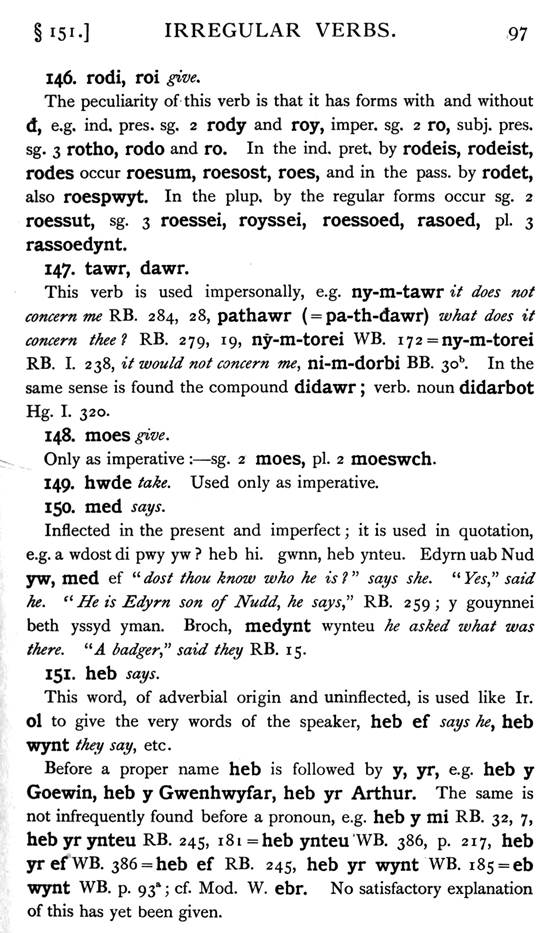

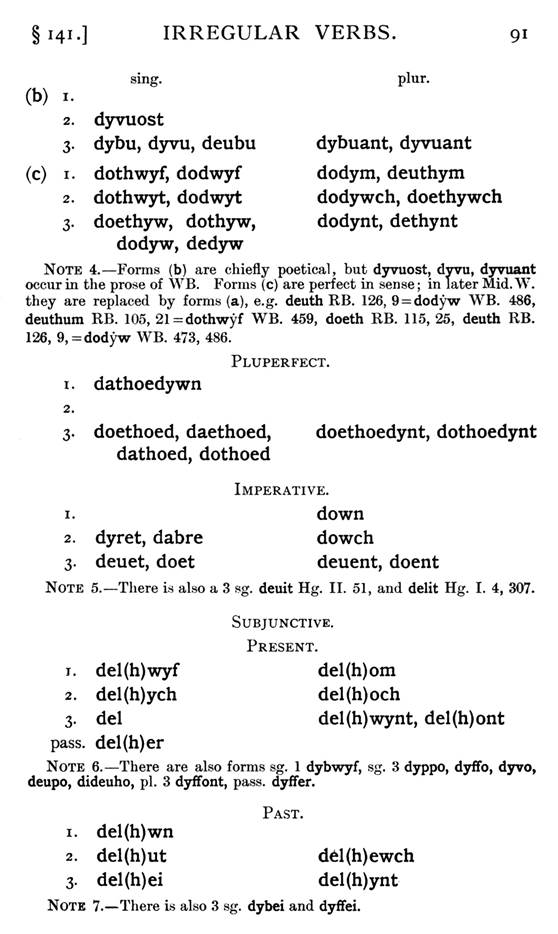

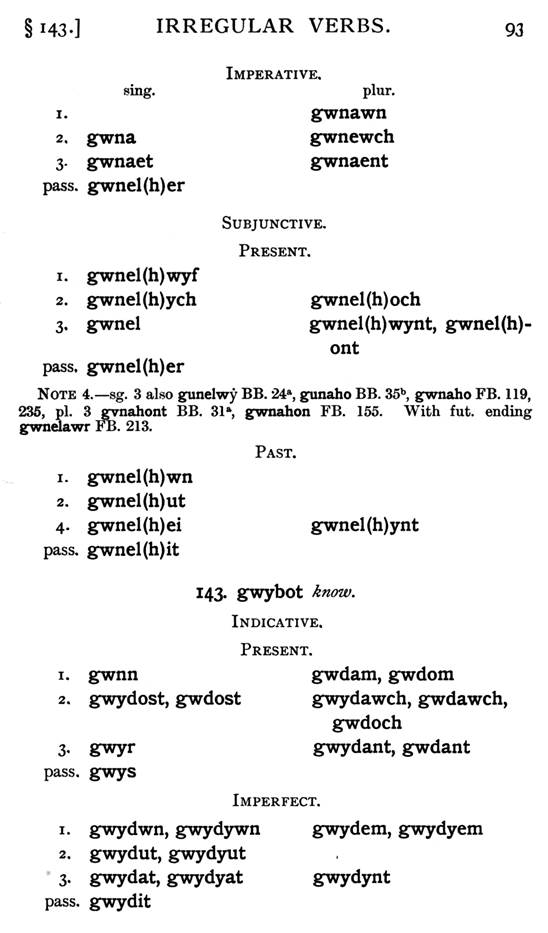

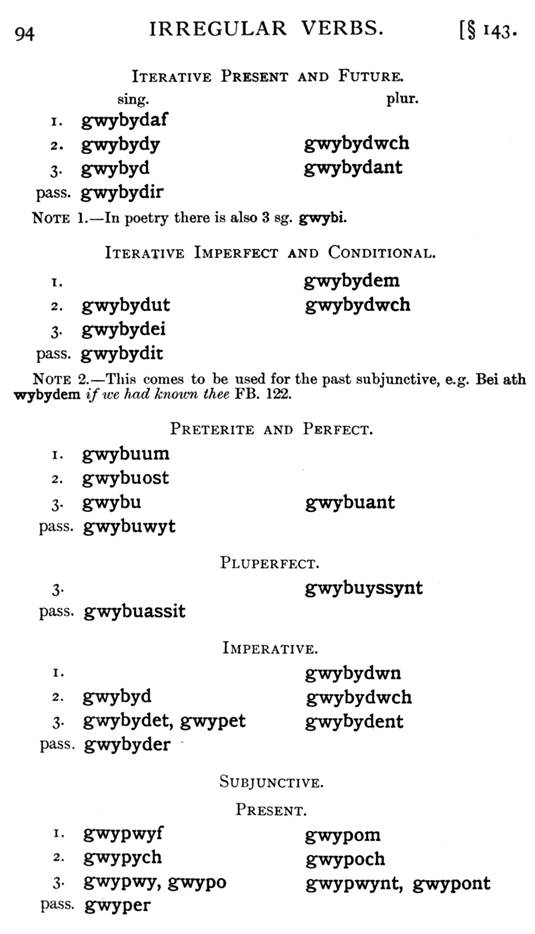

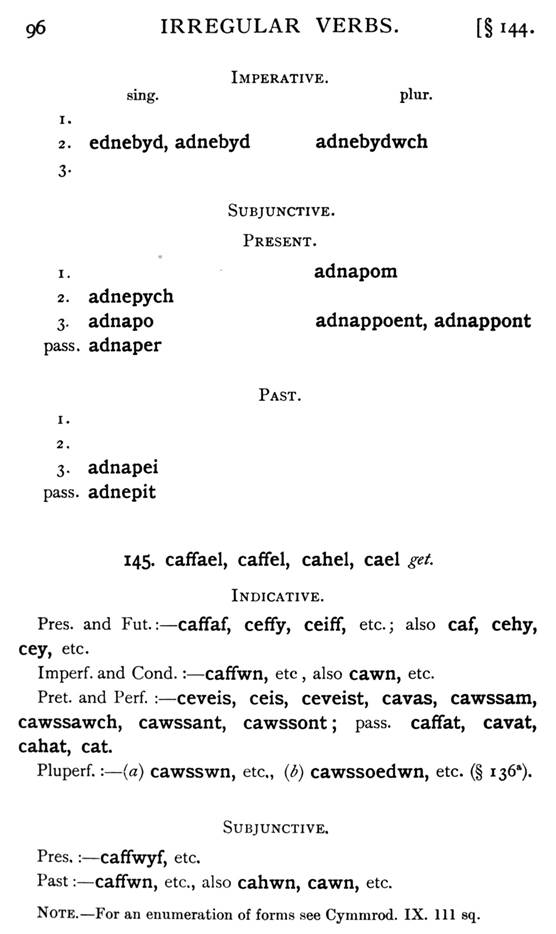

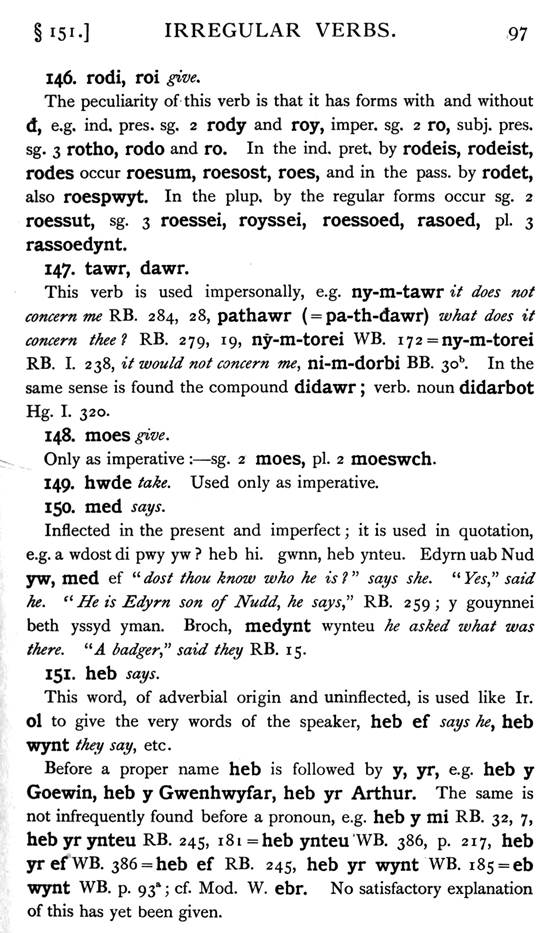

Irregular verbs: my net 140; dyvot 141; gwneuthur 142;

gwybot 143; adnabot 144; caffel 145; rodi 146; tawr 147;

moes 148; hwde 149; med 150; heb 151.

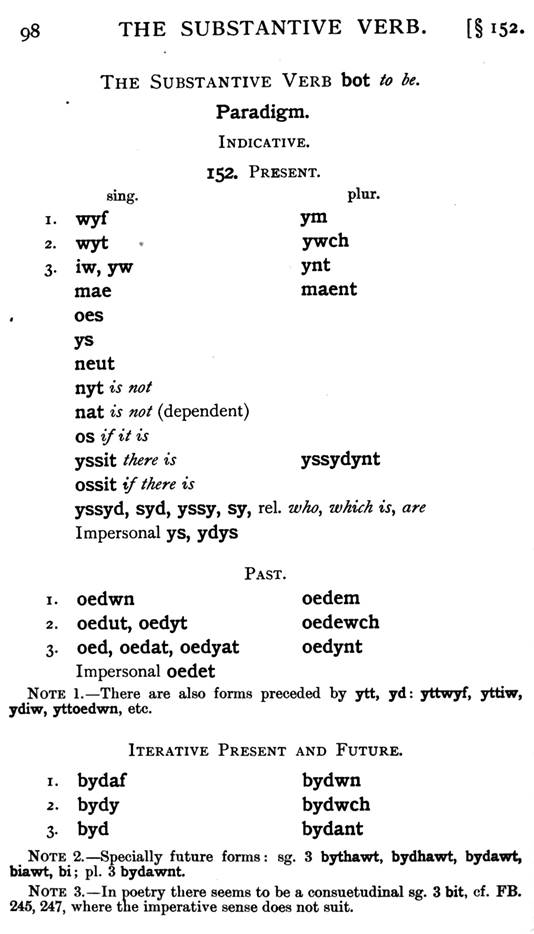

The substantive verb: paradigm 152; remarks on subst.

vb. 154; on copula 155 158; position of copula 159.

Compounds of bot 160-161. The Preposition 162 197. The Conjunction 198 234.

Negative particles 235 238. Interrogative particles 239 240. Responsive

particles 240 241. The Interjection 243 244.

READER

PAGE

I. Lear and his Daughters - 139

From Ystorya Brenhined y Brytanyeit, printed in

Red Book of Hergest, ed. J. Rhsand J. G. Evans, vol. ii,

pp. 64 69. The variants are from Brit. Mus. MSS. Add.

19,709.

II. The Story of Arthur - - 145

From the same source, pp. 184 232.

III. The Hunting of Twrch Trwyth - 193

An excerpt from the story of Kulhwch and Olwen. Chapters 1 6 are from the

White Book of Ehydderch (Peniarth MS. 4), with variants from the Red Book

(Rhys-Evans, vol. i, pp. 126128); chapters 725 from the Med Book (ib. p. 128,

1. 13 p. 142, 1. 19).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6893) (tudalen 00_xiii)

|

CONTENTS xiii

IV. The Procedure in a Suit for Landed Property 208 From the oldest copy of

the Laws of Howel Dda contained in the Black Boole of Chirk (Peniarth MS.

29). The variants are from Aneurin Owen's Ancient Laws of Wales, vol. i, pp.

142156. The text in the right-hand columns is a critical edition with

normalised spelling by Strachan.

V. The Privilege of St. Teilo - 222

From Evans-Rh^s Liber Landavensis, p. 118. The text in the right-hand columns

is a critical edition with normalised spelling by Strachan.

VI. Moral Verses - 225

From the Red Book, col. 1031, printed in Skene's Four Ancient Books of Wales,

vol. ii, pp. 249-250.

VII. Doomsday - 227

From the Book of Taliessin, printed in Four Ancient

Books, vol. ii, pp. 118 123. Strachan has made no use

of the variants printed in Myvyrian Archaiology, p. 72 ff.

VIII. To Gwenwynwyn - 233

From the Red Book, col. 1394, where it comes after

several poems ascribed to Llywelyn Vardd; printed in

Myvyrian Archaiology, p. 176a, where it is ascribed to

Cynddelw.

IX. Cynddelw to Rhys ab Gruffudd - 234

(a) from Black Book of Carmarthen, ed. J. G. Evans, fo. 39b; (6) from Red

Book, col. 1436.

X. A Religious Poem - 237

From Black Book of Carmarthen, fo. 20a, and from Red Book, col. 1159. XI. A

Dialogue between Ugnach Uab Mydno and

Taliessin - 239

From Black Book of Carmarthen, fo. 51a.

XII. Winter 241

From Black Book of Carmarthen, fo. 45a.

Glossary - -243

Appendix - - 277

Index - - 279

Corrigenda - - 293

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6895) (tudalen 00_xiv)

|

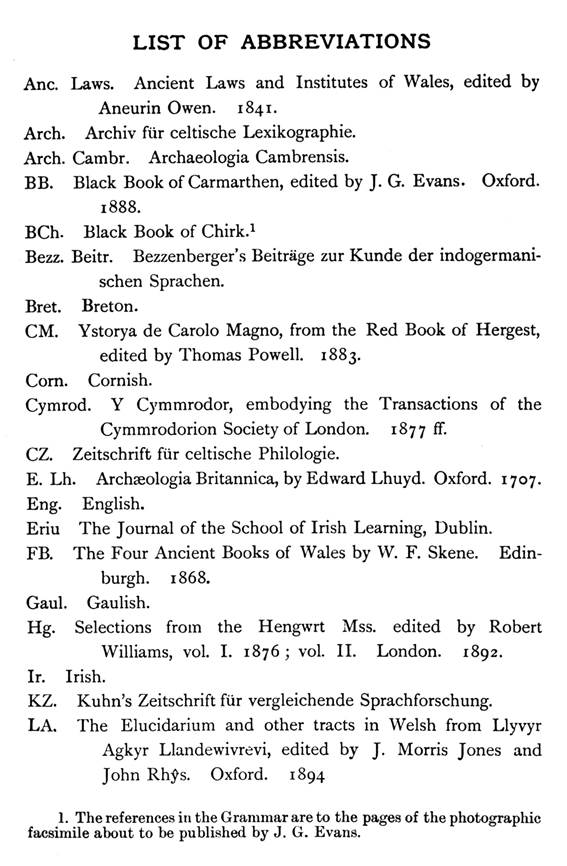

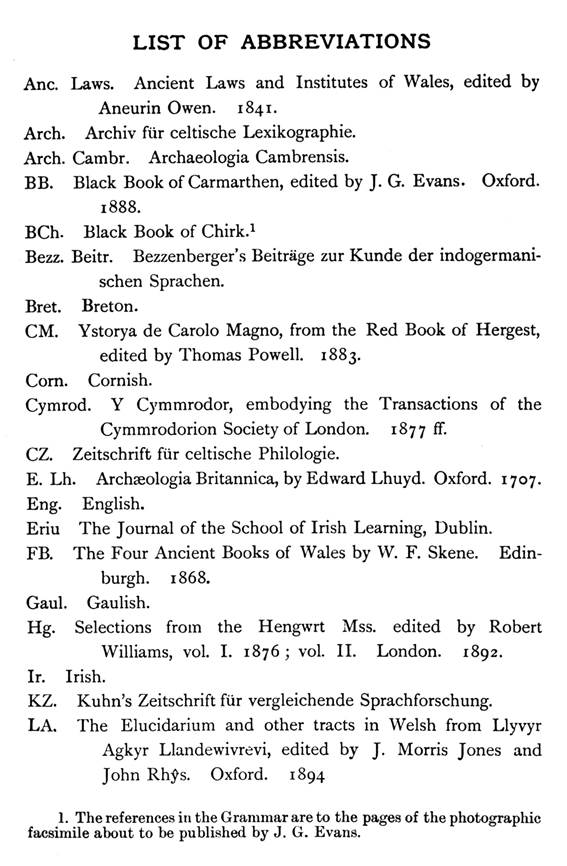

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

Anc. Laws. Ancient Laws and Institutes of Wales, edited by

Aneurin Owen. 1841. Arch. Archiv fur celtische Lexikographie. Arch. Cambr.

Archaeologia Cambrensis. BB. Black Book of Carmarthen, edited by J. G. Evans.

Oxford.

1888.

BCh. Black Book of Chirk. 1 Bezz. Beitr. Bezzenberger's Beitrage zur Kunde

der indogermani-

schen Sprachen. Bret. Breton. CM. Ystorya de Carolo Magno, from the Red Book

of Hergest,

edited by Thomas Powell. 1883. Corn. Cornish. Cymrod. Y Cymmrodor, embodying

the Transactions of the

Cymmrodorion Society of London. 1877 ff. CZ. Zeitschrift fur celtische

Philologie.

E. Lh. Archseologia Britannica, by Edward Lhuyd. Oxford. 1707. Eng. English.

Eriu The Journal of the School of Irish Learning, Dublin. FB. The Four

Ancient Books of Wales by W. F. Skene. Edin- burgh. 1868. Gaul. Gaulish. Hg.

Selections from the Hengwrt Mss. edited by Robert

Williams, vol. I. 1876; vol. II. London. 1892. Ir. Irish.

KZ. Kuhn's Zeitschrift fiir vergleichende Sprachforschung. LA. The

Elucidarium and other tracts in Welsh from Llyvyr

Agkyr Llandewivrevi, edited by J. Morris Jones and

John Rhs. Oxford. 1894

1. The references in the Grammar are to the pages of the photographic

facsimile about to be published by J. G. Evans.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6896) (tudalen 00_xv)

|

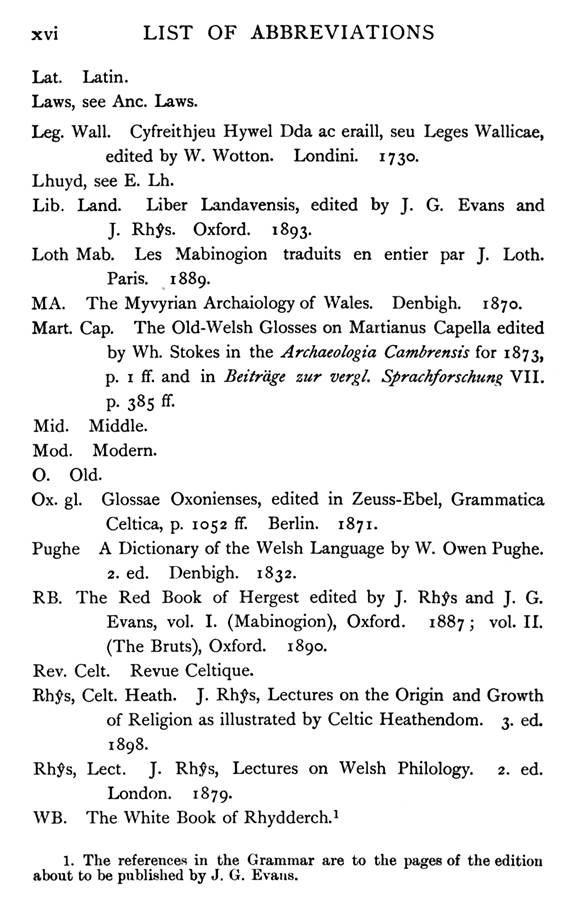

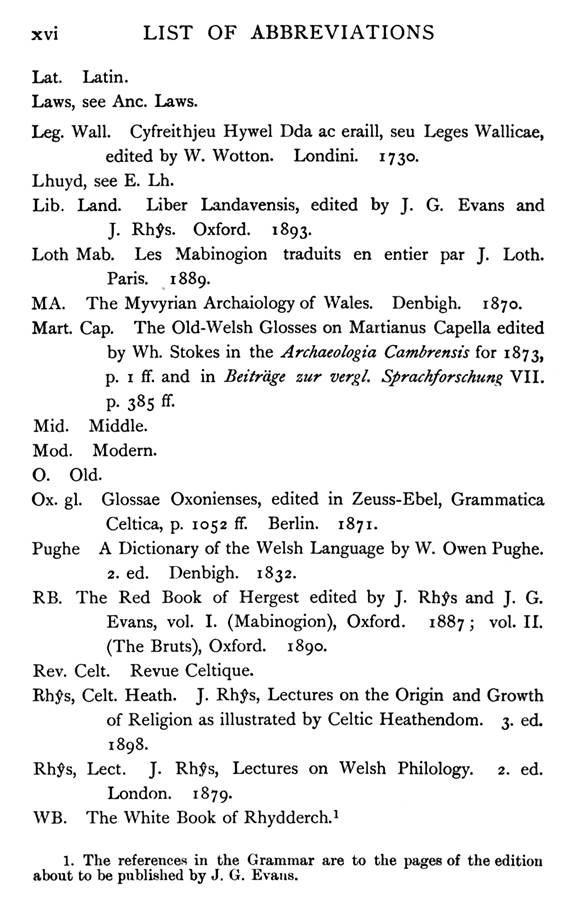

xvi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

Lat. Latin.

Laws, see Anc. Laws.

Leg. Wall. Cyfreithjeu Hywel Dda ac eraill, seu Leges Wallicae,

edited by W. Wotton. Londini. 1730. Lhuyd, see E. Lh. Lib. Land. Liber

Landavensis, edited by J. G. Evans and

J. Rhs. Oxford. 1893. Loth Mab. Les Mabinogion traduits en entier par J.

Loth.

Paris. 1889.

MA. The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales. Denbigh. 1870. Mart. Cap. The Old-

Welsh Glosses on Martianus Capella edited

by Wh. Stokes in the Archaeologia Cambrensis for 1873,

p. i ff. and in Beitrdge zur vergl. Sprachforschuns, VII.

p. 385 ff. Mid. Middle. Mod. Modern. O. Old. Ox. gl. Glossae Oxonienses,

edited in Zeuss-Ebel, Grammatica

Celtica, p. 1052 ff. Berlin. 1871. Pughe A Dictionary of the Welsh Language

by W. Owen Pughe.

2. ed. Denbigh. 1832. RB. The Red Book of Hergest edited by J. Rhs and J. G.

Evans, vol. I. (Mabinogion), Oxford. 1887; vol. II.

(The Bruts), Oxford. 1890. Rev. Celt. Revue Celtique. Rhs, Celt. Heath. J.

Rhs, Lectures on the Origin and Growth

of Religion as illustrated by Celtic Heathendom. 3. ed.

1898. Rhs, Lect. J. Rhs, Lectures on Welsh Philology. 2. ed.

London. 1879. WB. The White Book of Rhydderch. 1

1. The references in the Grammar are to the pages of the edition about to be

published by J. G. Evans.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6897) (tudalen 001)

|

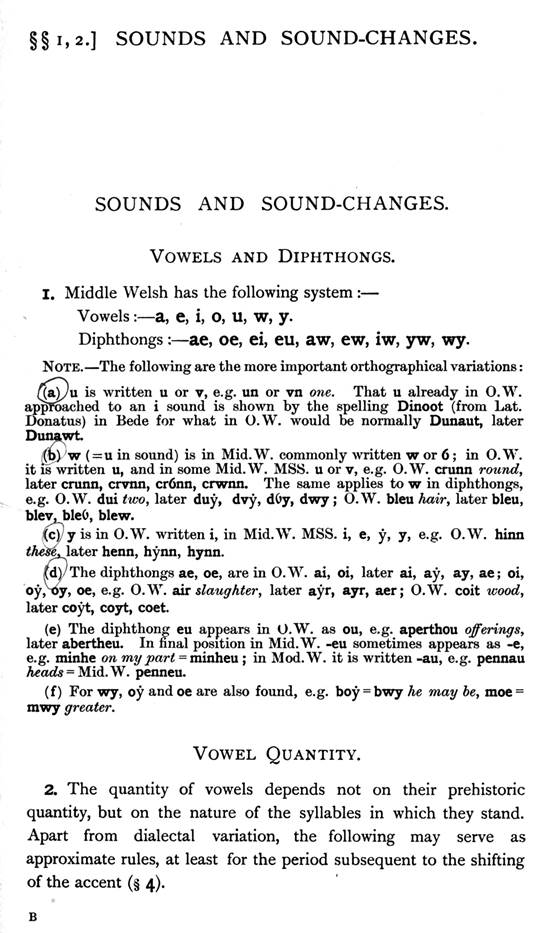

i,2.] SOUNDS AND

SOUND-CHANGES.

SOUNDS AND SOUND-CHANGES.

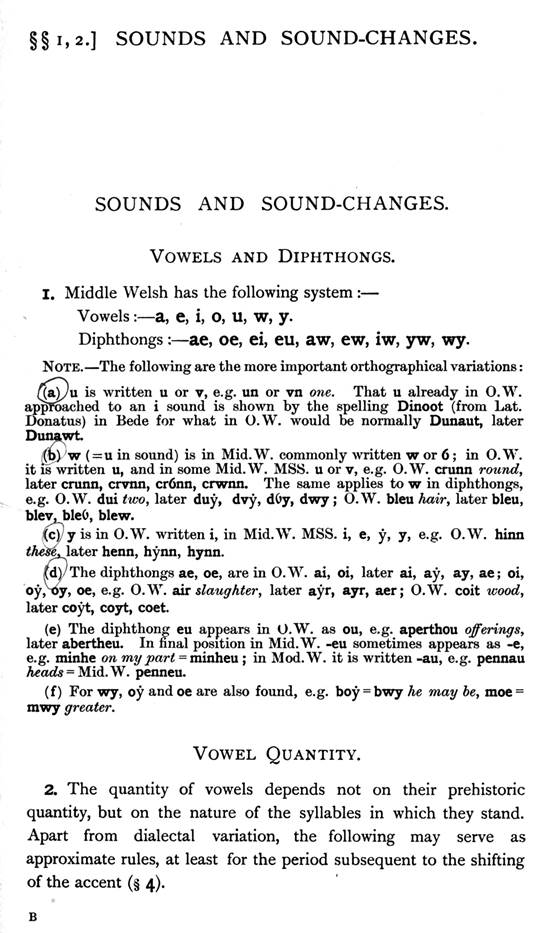

VOWELS AND DIPHTHONGS.

I. Middle Welsh has the following system: Vowels: a, e, i, o, u, w, y.

Diphthongs: ae, oe, ei, eii, aw, ew, iw, yw, wy.

NOTE. The following are the more important orthographical variations:

((aj/u is written u or v, e.g. un or vn one. That u already in O.W.

approached to an i sound is shown by the spelling Dinoot (from Lat. Donatus)

in Bede for what in O.W. would be normally Dunaut, later Dunawt.

(b) w ( = u in sound) is in Mid.W. commonly written w or 6; in O.W. it is

written u, and in some Mid.W. MSS. u or v, e.g. O.W. crunn round, later

crunn, crvnn, cr6nn, crwnn. The same applies to w in diphthongs, e.g. O.W.

dui two, later duy, dvy, dOy, dwy; O.W. bleu hair, later bleu, blev, bleO,

blew.

(c) y is in O.W. written i, in Mid.W. MSS. i, e, y, y, e.g. O.W. hinn these,

later henn, hynn, hynn.

(d) The diphthongs ae, oe, are in O.W. ai, oi, later ai, ay, ay, ae; oi, oy,

oy, oe, e.g. O.W. air slaughter, later ayr, ayr, aer; O.W. coit wood, later

coyt, coyt, coet.

(e) The diphthong eu appears in O.W. as ou, e.g. aperthou offerings, later

abertheu. In final position in Mid.W. -eu sometimes appears as -e, e.g. minhe

on my part = minheu; in Mod.W. it is written -au, e.g. pennau heads = Mid.W.

penneu.

(f) For wy, oy andoe are also found, e.g. boy = bwy he may be, moe = mwy

greater.

VOWEL QUANTITY.

2. The quantity of vowels depends not on their prehistoric quantity, but on

the nature of the syllables in which they stand. Apart from dialectal

variation, the following may serve as approximate rules, at least for the

period subsequent to the shifting of the accent ( 4).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6898) (tudalen 002)

|

2 SOUNDS AND

SOUND-CHANGES. [ 2.

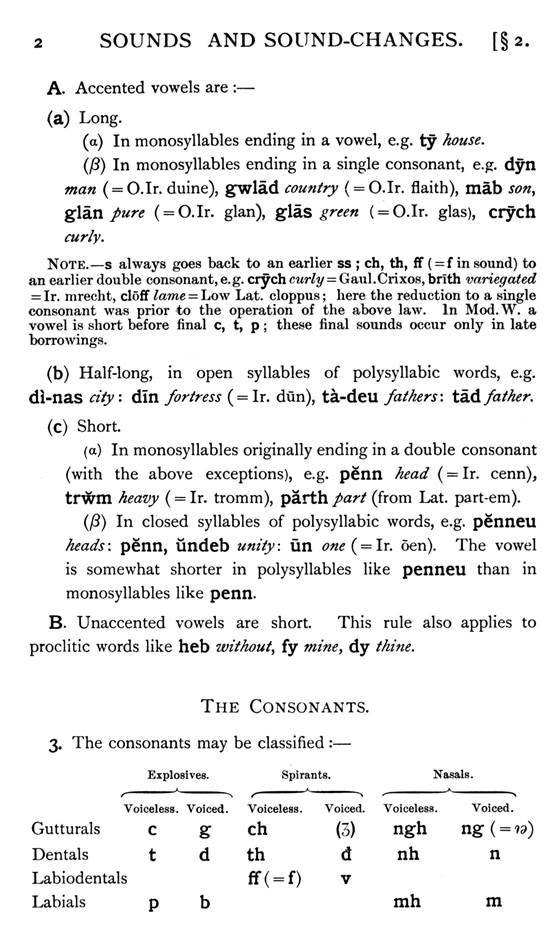

A. Accented vowels are:

(a) Long.

(a) In monosyllables ending in a vowel, e.g. ty house, (p) In monosyllables

ending in a single consonant, e.g. dyn man ( = O.Ir. duine), gwlad country ( =

O.Ir. flaith), mab son, glan pure ( = O.Ir. glan), glas green ( = O.Ir.

glas), crych curly.

NOTE. s always goes back to an earlier ss; ch, th, ff ( = f in sound) to an

earlier double consonant, e.g. crych curly = Gaul.Crixos, brlth variegated =

Ir. mrecht, cloff lame = Low Lat. cloppus; here the reduction to a single

consonant was prior to the operation of the above law. In Mod.W. a vowel is

short before final c, t, p; these final sounds occur only in late borrowings.

(b) Half-long, in open syllables of polysyllabic words, e.g. di-nas city: dm

fortress ( = Ir. dun), ta-deu fathers'. \aAfather.

(c) Short.

(a) In monosyllables originally ending in a double consonant (with the above

exceptions), e.g. perm head ( = Ir. cenn), trwm heavy ( = Ir. tromm), parth

part (from Lat. part-em).

(P) In closed syllables of polysyllabic words, e.g. penneu heads: perm, undeb

unity \ un one ( = Ir. oen). The vowel is somewhat shorter in polysyllables

like penneu than in monosyllables like penn.

B. Unaccented vowels are short. This rule also applies to proclitic words

like heb without, fy mine, dy thine.

THE CONSONANTS.

3. The consonants may be classified:

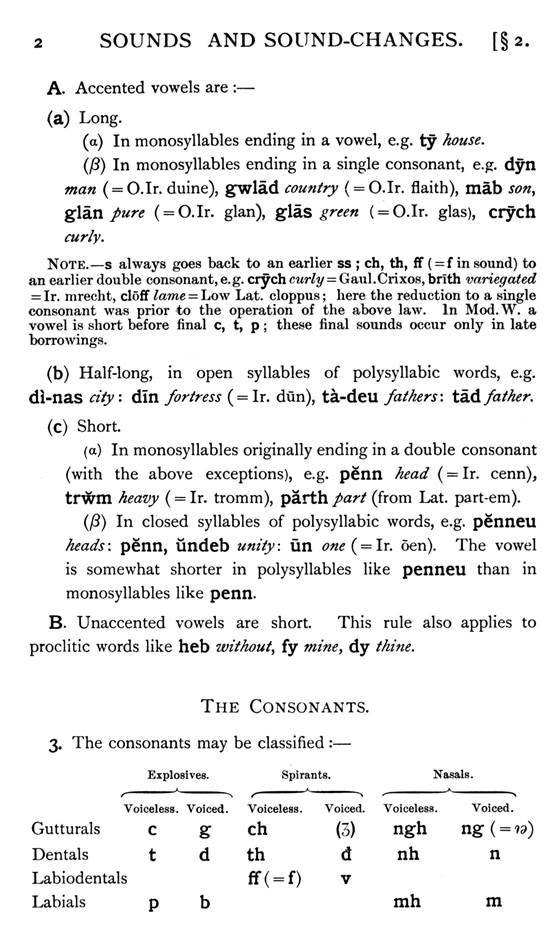

Explosives. Spirants. Nasals.

Voiceless. Voiced. Voiceless. Voiced. Voiceless. Voiced.

Gutturals c g ch (3) ngh ng ( = \

Dentals t d th d nh n

Labiodentals ff( = v

Labials p b mh m

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6899) (tudalen 003)

|

3.] SOUNDS AND

SOUND-CHANGES.

Liquids. Voiceless: 11, rh; voiced: 1, r. Semivowels: y, w.

C,"K.'l^,4- . r%

Sibilant: s. Breath: h.

NOTE. The following are the more important orthographical variations:

. W. c = k, both c and k found in Mid. W., c particularly at the end of a

word; e.g. O.W. cimadas fitting, Mid.W. kyvadas and cyvadas. In Mid.W. sc, sp

became sg, sb, e.g. kysgu by kyscu to sleep, ysbryd from Lat. spiritus.

(b) With regard to the graphic representation of the mediae the following may

be noted. In Ola British the symbols c, t, p were taken over from Latin with

their Latin values. In the course of time, before the loss of final

syllables, c, t, p, when they stood between vowels, or after a vowel and

before certain consonants, became in sound mediae g, d, b, but continued in

O. W. to be usually written c, t, p, e.g. trucarauc compassionate = Mid.W.

trugarawc, Mod.W. trugarog, dacr tear= Mid.W. dagyr, atar birds = Mid.W.

adar, datl gl. foro- Mid.W. dadyl, etn bird= Mid.W. edyn, cepistyr halter

(from Lat. capistrum) = Mid.W. kebystyr. In Mid.W. g, d, b are regularly

written in the interior of a word (except that c, t, p may appear in

composition, e.g. rac-ynys fore-island, kyt-varchpgyon fellow- horsemen,

hep-cor to dispense with, or in inflexion and derivation under the influence

of the simple word, e.g. gwlatoed, by gwladoed countries: gwlat, gwaet-lyt

bloody: gwaet). But final g is regularly expressed by c, and final d by t

(except in certain MSS. such as BB. which express d regularly by d and use t

to express the spirant d). Final p for b is not so universal; there are

found, e.g. pawp, pop, everyone, every by pawb, pob, and mab son, heb said.

rtcy The spirant f is in O.W. written f, and this orthography survives in

Mid.\Y., but the usual Mid.W. symbol is ff or ph. In O.W. the tenuis is

sometimes traditionally written for the spirant, e.g. cilcet gl. tapiseta

(from Lat. culcita) = Mod.W. cylched.

ft d) With regard to the graphic representation of the voiced spirants the

following may be noted, g, d, b, m were taken from Latin with their Latin values.

In time, between vowels and before and after certain consonants, they became

spirants 3> d, v, but continued to be written g, d, b, m, e.g. scamnhegint

gl. levant = later ysgavnheynt, colginn gl. aristam = Mod.W. colyn stiny,

cimadas fitting - Mod. W. cyfaddas, abal apple = later aval. In O.W. the

spirant g had already been lost in part, e.g. nertheint gl. armant by

scamnhegint, tru wretched = Ir. truag wretched. In Mid.W. the spirant g has

disappeared. The spirant d, which in Mod.W. is written dd, is in Mid.W.

usually expressed by d, e.g. rodi to ffive = Mod.W. rhoddi, except in certain

MSS. such as BB. which use the symbol t, e.g. roti = rhoddi. The spirant v in

Mid. W". is written u, uu, v, fu, f, the last particularly at the end of

a word, (e.g. cyuadas, cyvadas, cyfuadas, cyfadasjtt/in^=O.W. cimadas, Mod.W.

cyfaddas), in Mod.W. f; in certain MSS., however, such as BB. it is expressed

by w, e.g. calaw reeds = calaf. In O.W. final v has been already lost in

part, e.g. lau hand = Ir..lam, and in the course of time it tends more and

more to disappear, .e.g. in Mid.W. the superlative ending -af appears also as

-a.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6900) (tudalen 004)

|

SOUNDS AND SOUND-CHANGES.

[3.

(e) The guttural nasals ng (i.e. 99 as in Eng. sing} and ngh are often

written g and gh, e.g. llog = llong ship, agheu death = angheu.

ff) Jrhe voiceless 1 is in O.W. written 1 at the beginning of a word, e.g.

lax?--nand= Mid.W. Haw, elsewhere 11, e.g. mellhionou gl. violas. In Mid.W.

it is in all positions written 11 or II. For the voiceless r=Mod. W. rh,

Early Welsh has no special symbol; it is written r.

e semivowel y is in O.W. written i, e.g. iechuit gl. sanitas, u gl. violas:

in Mid.W. it is expressed by i, e.g. ieith speech, or y, e.g. engylyon

angels. In the initial combinations hw (from an earlier sv), which in Mid. W.

appears as chw or dialectally as hw, and gw (from an earlier w), w is in O.W.

expressed by u, e.g. hui yon = Mid.W. chwi, guin wine (from Lat. uinum) =

Mid.W. gwin; in Mid.W. it is commonly written 6, w, but in some MSS. u, v,

e.g. g6ynn, guynn, gvynn white but in Mid.W. O.W. initial guo- becomes go-.

In other positions in Mid.W. w is expressed by 6, w, sometimes by u, uu, v; here

it comes from O. W. gu, e.g. O.W. neguid new = Mid.W. newyd, neuyd, neuuyd,

nevyd, O.W. petguar four Mid.W. petwar, petuar, petvar. It is to be noted

that initial gw from an earlier w does not form a syllable even before a

consonant; thus gwlad country from *ulatis = Ir. flaith kingdom is

monosyllabic.

THE ACCENT.

4. In accented words in Mod.W. the accent, with certain excep- tions, falls

on the penult, e.g. pechadur sinner, tragywyddol eternal. This accentuation,

however, has replaced an earlier system which was common to all the British

dialects and is still preserved in the Breton dialect of Vannes, according to

which the accent fell on the last syllable, e.g. parawt ready. The effect of

this earlier accentuation is seen in the weakening of vowels in syllables

that according to the later system would have borne the accent, e.g.

pechadiir sinner from Lat. peccatorem: pechawt sin from Lat. peccatum, O.W.

Dimt, Mid.W. Dyvet: Demetae, O.W. hinham, Mid.W. hynhaf oldest-, hen old,

Mid.W. llynghes/^/: llong^O.W.cilche't, Mid.W. cylchet from Lat. culcita,

Mid.W. drysseu doors: drws door. The date of the change of accent has not yet

been accurately fixed; with it seems to be connected the change of aw to o in

final syllables, e.g. Mid.W. pechawt = Mod.W. pechod, of which there are

sporadic instances in early Mid.W., e.g. rymdywod ( = rym dywawt), BB.

28" 13.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6901) (tudalen 005)

|

7-] SOUNDS AND

SOUND-CHANGES. 5

CHANGES OF VOWELS.

Changes due to a vowel which follows or which originally followed.

5. The quality of a vowel is liable to be influenced by the vowel of the

following syllable. Sometimes the infecting vowel remains, e.g. Ceredic from

Old British Coroticus, eyt goes = O.W. egit by O.W. agit, menegi to show by

managaf / show. Sometimes the infecting vowel has been lost, e.g. trom f. by

trwm m. heavy from *trumma, *trummos (where it will be seen that the short

vowel of the masculine exerted no influence, while the long vowel of the

feminine did), brein ravens (by bran raven) from *bram, earlier *branoi, Cyrn

horns (by corn horn) from *cornl, earlier *cornoi, dreic dragon (by pi.

dragon) from *draci, from *dracu from Lat. draco, ceint I sing (by cant he

sang) from *cantl, from *cantu, from * canto, Meir from Lat. Maria, yspeil

spoil from Lat. spolium. The infection may extend back more than one syllable

e.g. menegi: managaf, deveit sheep: davat a sheep. The following are the

changes of the kind which are important for inflection:

A. CHANGES DUE TO AN / VOWEL PRESERVED.

6. a > e, e.g. ederyn a bird-, adar birds, peri to cause: paraf / cause,

edewis he promised: adaw to promise, cerit was loved: caru to love, llewenyd,

O.W. leguenid/tfy: llawen/<?>w/.$-.

ae > ei, e.g. meini stones: maen stone, seiri artisans \ saer.

B. CHANGES DUE TO A LOST VOWEL.

7. (a) The lost vowel is a.

y > e, e.g. berr f.: byrr m. short. The variation in brith, f. braith

variegated is of the same kind; brith comes from *mrictos, braith from

*mrecta, *mricta.

w > o, e.g. trom f.: trwm m. heavy.

(b) The lost vowel is I (of various origin).

a > ei, e.g. meib sons: mab son, meneich monks \ manach

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6902) (tudalen 006)

|

6 SOUNDS AND

SOUND-CHANGES. [ 7.

monk; geill is able: gallaf / am able, gweheird he forbids-. gwahardaf I

forbid, ceint I sang-, cant he sang.

ae > ei, e.g. mein stones-, maen stone, Seis Saxon (from *Saxi, *Saxu,

Saxo): Saeson (from Saxones).

Final aw > CU, y, e.g. teu is silent: tawaf / am silent, edeu, edey, edy

leaves: adawaf / leave.

e > y, e.g. hyn older: hen old, cestyll castles: castell castle, gwyl

sees: gwelaf / see, gweryt helps: gwaret to help.

o > y, e.g. pyrth gates: porth gate, escyb bishops: escob bishop, tyrr

breaks: torraf / break, egyr opens: agoraf / open, try turns: troaf / turn.

oe > wy, e.g. wyn lambs (from *ognl): oen lamb (from *ognos).

w > y> e -g- bylch gaps: bwlch gap, yrch roebucks: ywrch roebuck.

NOTE 1. In the 3 sg. pres. indie, act. of the verb the prehistoric ending is

uncertain; geill might come phonetically from either *gallit or *gallyet. In

verbs containing radical o, infection is found only in the 3 sg. pres. indie,

act., e.g. tyrr he breaks, but tprri to break, torrynt they broke, torrir is

broken. In shaping the conjugation of these verbs analogy seems to have

played a large part, but the details of the development are obscure.

NOTE 2. It will be observed that in the case of i infection the infection

extends back to a preceding a, e.g. deveit, edewis, egyr.

NOTE 3. There is also a variation between ae and eu, ei, e.g. caer city: pi.

ceuryd, ceyryd; aeth he went: euthum / went.

Vowel Variation due to Accent.

8. Celtic a became in British 6; the 6 stage is seen in Bede's Dinoot from

Lat. Donatus, and in early Irish loanwords which came from Latin through

Britain, e.g. trindoit Trinity from Lat. trinitatem. In Welsh, during the

period of the older accentuation this 6 became in accented syllables aw, e.g.

Dunawd, trindawt, in unaccented syllables o. To this are due variations like

O.W. cloriou gl. tabellae: sg. clawr, Mid.W. marchogyon horsemen-. marchawc

horseman, moli to praise: mawl praises, and the proclitic pob every ( = Ir.

each): accented pawb everyone ( = Ir. each). After the shifting of the accent

from the ultima to the penult, aw in accented words of more than one syllable

became o,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6903) (tudalen 007)

|

ii.] SOUNDS AND

SOUND-CHANGES. 7

e.g., Mod.W. marchog = Mid.W. marchawc, but Mod.W. pawb = Mid.W. pawb. For

other instances of vowel weakening in unaccented syllables see 4.

PROTHETIC VOWEL.

9. Before words which in O.W. began with s + consonant there developed in the

Mid.W. period a prothetic y, e.g. ysgriven writing-. O.W. scribenn, ystavell

chamber-. O.W. stabell, ysteoAxLr packsaddlei O.W. strotur, yspeil spoil:

O.W. *speil,

from Lat. spolium.

EPENTHETIC VOWEL.

Before a final liquid, nasal, or v, an epenthetic vowel is often written,

which, however, does not count metrically as a syllable.

(a) Consonant + 1, e.g. mynwgyl by mynwgl /**:/ = Mod. W. mynwgl; kenedel,

kenedyl by kenedl race = O.W. cenetl, Mod.W. cenedl; kwbwl, kwbyl by kwbl

whole = Mod.W, cwbl; tavyl sling = Mod.W. tafl.

(b) Consonant + r, e.g. hagyr by hagr ugly = Mod.W. hagr; lleidyr by lleidr

roMer=Mod.W. lleidr; llestyr vessel =Q.\N. llestr, llestir, Mod.W. llestr;

dwvyr, dwvwr by dwvr water =Mod.W. dwfr.

(c) Consonant + m, e.g. talym space = Mod.W. talm.

(d) Consonant + n, e.g. gwadyn by gwadn sole = Mod.W. gwadn; dwvyn deep =

Mod.W. dwfn.

(e) Consonant + v, e.g. dedyf custom = Mod.W. deddf; baraf, baryf beard =

Mod.W. barf; twrwf, twryf by twrf noise.

CONSONANTAL CHANGES.

II. The following changes of consonants in combination are of importance for

accidence:

(a) In the Indo-Germanic parent language d or t + 1 became t*t, and ft in

Celtic became SS, e.g. W. Has was killed '= Ir. -slass from *slat s tos: Had

kill= Ir. slaidid hews.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6904) (tudalen 008)

|

8 SOUNDS AND

SOUND-CHANGES. [ii.

(b) act>aeth, or, with I infection, >eith; ect>eith; wet >wyth;

wen, wgn>wyn, e.g. aeth he went from *act, but imdeith / travelled from

*actl (earlier *actu, *act6): Mid.W. eyd = O.W. egit, agit; dyrreith he

returned, from *-rekt:

>/reg-; amwyth he defended from *amukt: amwgaf / defend, of which the

verbal noun is amwyn from *amucn...

(c) rt>rth, e.g. cymmerth he took from *com-bert: cym- meraf / take.

(d) Before a labial n becomes m, e.g. y maes in the field from yn maes.

(e) nd, mb > nn, mm, e.g. vyn nyvot, vy nyvot my coming from vyn dyvot; ym

mwyt, y mwyt into food from yn bwyt.

(f) nc, nt, mp. At the end of a word nc, mp remained, e.g. ieuanc

jw&flg', pumpjfctf; nt remained in accented monosyllables, e.g. dant

tooth (but proclitic can, gan with = QW. cant); in words of more than one

syllable it appears as nt or n, e.g. ugeint and ugein twenty, carant and

caran they love. In the interior of a word nc, nt, mp develop regularly in

the penultimate syllable to ng, nn, mm, in the antepenult to ngh, nh, mh,

e.g. tranc cessation: trengi to cease-, angen necessity (from *ancen = Ir.

ecen): anghenawc necessitous-, O.W. hanther half, later banner; dant tooth-,

danned teeth-, danhedawc toothed; O.W. pimphet fifth, later pymmet; cymmell

compulsion (from Lat. compello): pi. cymhellyon. The regular development,

however, is liable to be affected by analogy.

NOTE 1. The cause of the different treatment in the penult and the antepenult

is the accent. In early W. the accent was on the last syllable ( 4); the

syllable immediately preceding the accent would be most weakly accented, the

syllable before that would have a secondaiy accent, e.g. anghenawc,

danhedawc, cymhelly6n.

fg) Before h

(a) g, d, b become tenues, e.g. teckaf most beautiful from *teg-haf: tec

(phonetically teg) beautiful, tebycko from *tebyg-ho he may think: tebygu to

think, plyckau to fold from *plyg-hau: plyc (phonetically plyg) fold;

calettaf hardest from *caled-haf: calet (phonetically caled) hard, cretto he

may believe from *cred-ho:

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6905) (tudalen 009)

|

12.] SOUNDS AND SOUND-CHANGES.

9

credu to believe, bwyta to eat from *bwyd-ha: bwyt (phonetically bwyd) food-,

cyvelyppaf most like from *cyvelyb-haf: cyvelyp (phonetically cyvelyb) like,

attepo from *ad-heb-ho he may answer: attebu, digaplo he may cease to

calumniate from *digabl-ho '. digablu, llwyprawt from *llwybr-hawt will

course-. llwybraw to course.

((3) d becomes th, e.g. diwethaf last from *diwed-haf: diwed end, rotho he

may give from *rod-ho: rodi to give, rythau to set free from *ryd-hau; ryd

free.

(y) v becomes f, e.g. tyffo he may grow from *tyv-ho: tyvu to grow, dyffo he

may come: dyvod to come, coffau to remember from *COV-hail; cof memory.

NOTE 2. Instances of ff from v-h are not numerous, they have commonly been

replaced by analogical forms, e.g. araf-hau to make gentle, digrif-af most

entertaining. So th from d + h becomes rarer and rarer in Mid.W., where e.g.

rotho is replaced by rodho and rodo; the old forms are most persistent in the

case of the tenues c, t, p. (cf. no)

(f) th + d>th, e.g. athiffero who may defend thee from ath-differo. But

here commonly the d is written etymologically.

(g) d + d became apparently d, e.g. adyn wretch from ad-dyn (ad- = lr. aith-,

with sense of Lat. re-).

SOUND-CHANGES WITHIN THE SENTENCE.

12. Within the sentence closely connected word groups are liable to changes

similar to those that take place within individual words. As within the word

vowel-flanked consonants were reduced, e.g. CCgin kitchen from Lat. coquina,

niver number from Lat. numerus, so in a word group, e.g. *t6ta mara great

people became tud vawr. As within the word nc became ngh, nt became nh, mp

became mh ( II), nd became nn, e.g. crwnn round by Ir. cruind, mb became mm,

e.g. camm crooked from Old British cambos, so in word groups, e.g. vyn cynghor

my counsel became vy ghynghor, vyn penn my head became vym penn, vy mhenn,

vyn dyvot my coming became vyn nyvot, yn bwyt into food became ym mwyt, y

mwyt. But, on the one hand, a

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6906) (tudalen 010)

|

10

CONSONANT MUTATIONS.

[.

particular mutation may spread analogically, if it becomes connected with

some grammatical function; thus in Welsh it became the rule that after all feminine

nouns in the singular a following adjective was mutated, though in Celtic

only certain classes of feminine nouns ended in a vowel. On the other hand,

the change may analogically disappear altogether, or the mutation may be

restricted to certain phrases as in the case of the nasal mutation after

numerals ( 20c). In sound groups there are three kinds of initial change (i)

vocalic mutation or lenation, which originated from cases where the preceding

member of the group originally ended in a vowel, (2) nasal mutation where the

preceding member originally ended in n, (3) spirant mutation where the

preceding member ended in certain consonants, most commonly s but also C.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6907) (tudalen 011)

|

NOTE. In reading Early

Welsh texts the student must be careful not to be misled by the orthography,

which does not consistently express the initial changes. Thus if he should

meet with, e.g. y gwlat the country for y wlat, or vyn dy vot for vyn nyvot,

that is only an archaistic or etymological orthography which is no evidence

of the actual sound at the time.

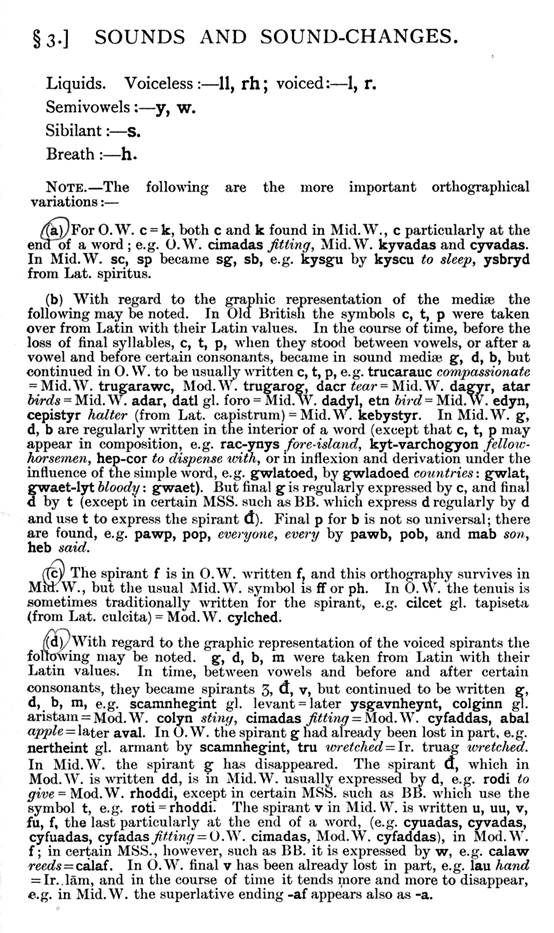

Tenues

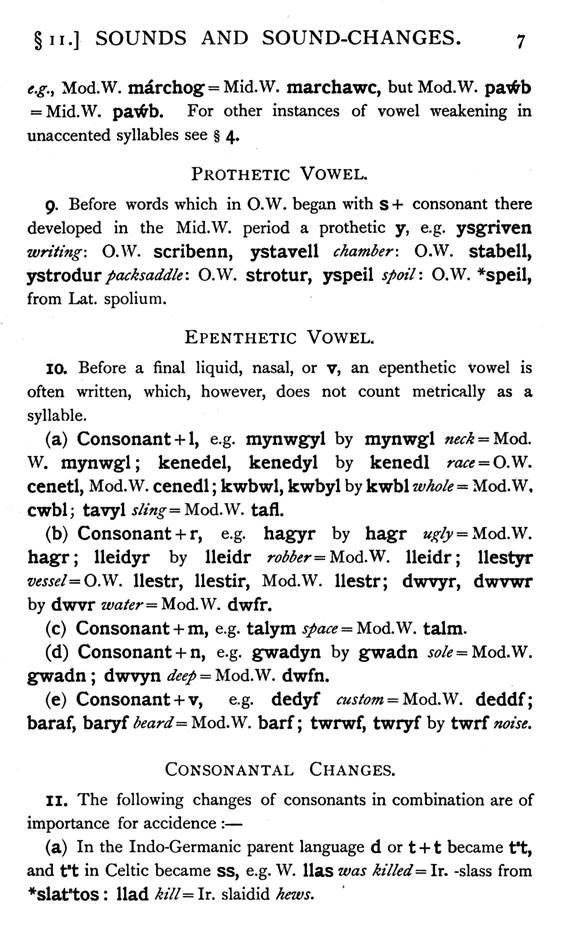

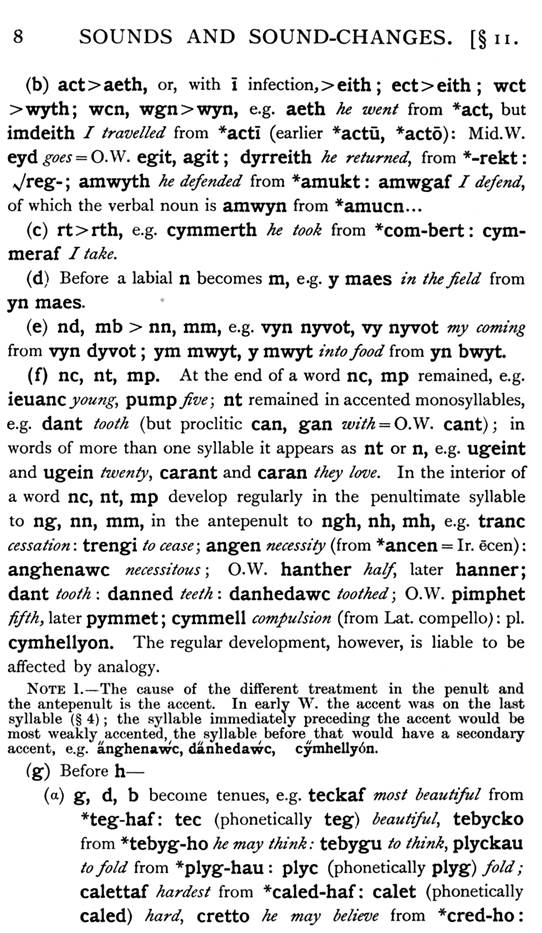

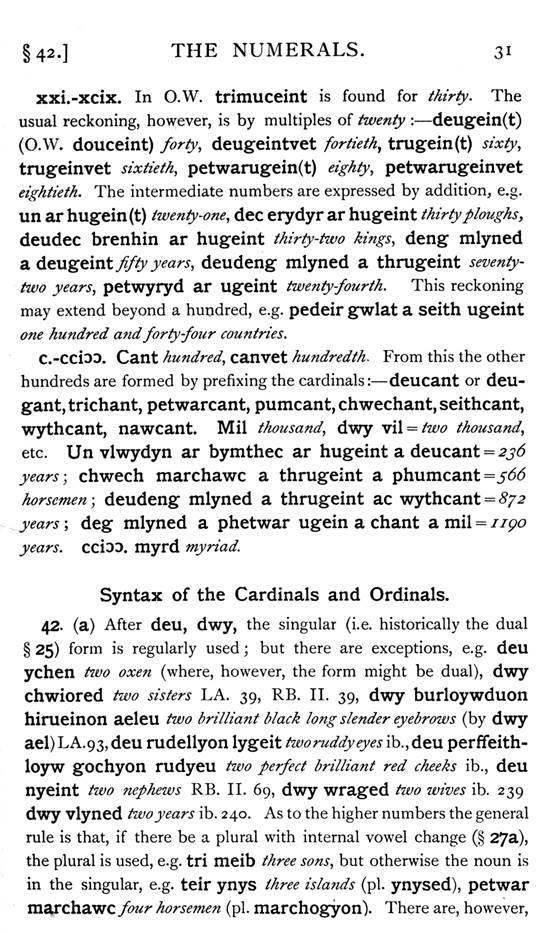

13. Table of Consonant Mutations.

radical vocalic nasal

C ... corn ... gorn ... nghorn

t ... tat ... dat ... nhat

p ... prenn ... brenn ... mhrenn

(S -

gwr

... wr

. . . ngwr

Mediae ( d ...

dyn

. . . dyn

. . . nyn

(b ...

baryf

. . . varyf

. . . maryf

I' 'A f U -

Liquids { t rh...

Haw rhan

. . . law

. . . ran

Nasal m ...

mam

. . . vam

spirant Chora that phrenn

NOTE 1. In vocalic mutation g became first the spirant 3 which was early lost

( 3d). From the fact that initial g was thus lost, many words which

originally began Avith a vowel in time assume an initial g; e.g. y ord his

hammer (=Ir. ord) resembled externally y wr his man, and this superficial

resemblance led to gord (for ord) like gwr. The principle is the same as in

the development of initial f before a vowel in Mid. Ir.

NOTE 2. As in Mid.W. the spirant is commonly written d ( 3d), the vocalic

mutation of initial d is not discernible in writing.

NOTE 3. In Mid.W. initial rh is written r, so that the unmutated and the

mutated forms are indistinguishable ( 3f).

i6.] CONSONANT MUTATIONS. u

Vocalic Mutation or Lenation.

14. The history of Welsh lenation has still to be written. In some respects,

particularly with regard to lenation after the verb, the subject is full of

difficulty. In the development of lenation analogy played a large part, so

that to some extent the usage would differ at different periods. And the

fixing of the rules of lenation for a particular period is complicated by the

fact that the mutation is not consistently expressed in writing. The

following are the chief facts about lenation in Mid. W. prose; the material

is taken from the Red Book of Hergest.

15. General exception to the rules of lenation. After final n and r initial

11 and rh were regularly unmutated, e.g. yn llawen gladly, y Haw = O.W. ir

lau the hand. For rh the rule is seen in Mod.W., e.g. yn rhydd freely, y rhan

the part. As rh was not written in Mid. W. this distinction is not

discernible there.

A. LENATION OF NOUN AND ADJECTIVE (INCLUDING NOMINAL

ADJECTIVAL PRONOUNS).

16. (a) After the article.

After the article in the sg. fern, the initial consonant of a following noun

or adjective is lenated, e.g. y gaer the city, yr dref to the town, y

vrenhines the queen. But y Haw the hand ( 15).

(b) After the noun.

(a) After a noun in the feminine singular or the dual an adjective is

lenated, e.g. morwyn benngrech velen a curlyhaired auburn maid, deu vilgi

vronwynnyon vrychyon two whitebreasted brindled hounds. Also when the

adjective is separated from the noun, e.g. kaer uawr a welynt, vwyhaf or byt

they saw a large town, the largest in the world.

NOTE 1. After the masc. sg. and the plur. lenation of the comparative is

found in sentences of the following type: ny welsei dyn eiryoet llu degach

.... noc oed hwnnw no man had ever seen a host fairer than that KB. 90, 13;

na welsynt llongeu gyweiryach y hansawd noc wynt that they had not seen ships

better equipped than they KB. 27, 3.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6908) (tudalen 012)

|

12 CONSONANT MUTATIONS. [

16.

(ft) After a noun in the fern. sg. or the dual a following genitive is

lenated when it is equivalent to an adjective, e.g. kist vaen a stone chest;

deu vaen vreuan two millstones.

NOTE 2. The genitive is lenated after meint, ryw, kyvryw and sawl ( 76-7),

e.g. y veint lewenyd the amount of gladness; pa ryw wysc what kind of dress?

kyvryw wr such a man y sawl vrenhined all the kings. Further, the genitive of

proper names is lenated after certain nouns, e.g. Cadeir Vaxen Maxen's Seat;

Caer Vyrdin Carmarthen; Llan badarn lit. Padarn's Church; Ynys Von Island of

Mon; Eglwys Veir Mary's Church; Gwlat Vorgan the land of Morgan; pobyl

Vrytaen the people of Britain; ty Gustenin the house of Custenin (cf. Mod.W.

ty Dduw); mam Gadwaladyr mother of Cadwaladr Branwen verch Lyr Branwen

daughter of Llyr; gwreic Vrutus wife of Brutus; deu vab Varedud two sons of

Maredud.

(y) After proper nouns theie is lenation of a following noun or adjective

denoting a characteristic of a person, e.g. Llud vrenhin King Z/7/d, Peredur

baladyrhir Peredur of the long spear.

NOTE 3. The initial consonants of mab son and merch daughter are lenated,

e.g. Pryderi uab Pwyll Pryderi son of Pwyll, Aranrot verch Don Aranrod daughter

of Don.

NOTE 4. Further instances of lenation in apposition are, e.g. ewythred Arthur

oedynt, urodyr y uam they were uncles of Arthur, his mother's brothers,

Giluaethwy ac Euyd . . . y nyeint, ueibion y chwaer Gilvaethwy and Evyft. his

nephews, his sister's sons. Aranrot uerch Don dy nith, uerch dy chwaer

Aranrot daughter of Don thy niece, thy sister's daughter.

(8) Lenation is found in the genitive of the verbal noun, particularly when

it is separated from the governing word, e.g. menegi uot y crydyon wedy

duunaw declaring that the cobblers had united; a dyuot . . . yn y vedwl uynet

y hela and it came into his mind to go to hunt; a ryuedu o Owein yr mackwy

gyuarch gwell idaw and Owein wondered that the youth should greet him.

(c) After the adjective.

(a) When an adjective in the positive degree precedes, the noun is lenated,

e.g. brawdoryawl garyat brotherly love, dirvawr wres excessive heat,

amryuaelyon gerdeu divers songs. So after the pronominal adjective holl all,

e.g. noil gwn all the dogs, holl wraged all the women.

NOTE 5. For the comparative the material to hand from RB. is scanty; with

lenation: yn llei boen less pain 146, without lenation: mwy gobeith greater

hope 95, muscrellach gwr a more helpless man 13. In KB. II.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6909) (tudalen 013)

|

16.] CONSONANT MUTATIONS. 13

there are some instances of lenation after mwy more. After the superlative in

RB. non-lenation seems to be the rule; in RB. II. lenation is more frequent.

NOTE 6. In Celtic, when the adjective preceded the noun, it formed a compound

with it, e.g. hen-wrach old hag ( 34a), and in composition the lenation of

the second element was regular, e.g. eur-wisc golden dress, bore-vwyt morning-food,

breakfast. In Welsh, when the adjective came to be used freely before the

noun, the lenation of the old compounds was retained in the positive,

NOTE 7. On the analogy of lenation in compound words and of lenation of the

noun following the adjective, in poetry, when the genitive precedes the noun,

it may lenate, e.g. byd lywyadwr the ruler of the world, o Gymry werin of the

host of the Cymry.

(p) When an adjective is repeated, e.g. mwy vwy vyd greater and greater will

be.

(d) After YN forming adverbs, and with predicative nouns and adjectives (

35), e.g. yn vynych often, yn borth as a help, yn wreic as a wife. But yn

llawen gladly ( 15).

NOTE 8. With regard to their influence upon a following word it is necessary

to bear in mind that predicative yn lenates, that yn in is followed by the

nasal mutation ( 20b) and that yn with the verbal noun, e.g. yn mynet going (

I26a), does not affect a following consonant.

(e) After numerals.

(a) After cardinal numbers.

un one. After the fern., lenation seems to be regular, e.g. un wreic one

woman, un vil one thousand, yr un gerdet the same going. Initial 11 is

regularly uninfected, e.g. un llynges one fleet. After the masc. the usage

seems to vary, e.g. vn geir one word RB. 197 = WB. 123, but vn eir RB. II.

222, yr un march the same horse RB. 9, but neb vn varchawc any horseman RB.

II. 278, yn un uaes in one field RB. 114.

NOTE 9. In Irish, din regularly mutates a following consonant. According to

Rowlands, Mod.W. un mutates in the fern.

deu, dwy two. After these lenation is regular, e.g. deu barchell two pigs,

deu lu two hosts, dwy verchet two daughters.

But deu cant two hundred RB. II. passim.

chwech, chwe six: chwech wraged six women RB. 18, 16; but chwe blyned six

years RB. II. 387, 404.

Seith seven: seith gantref seven cantreds RB. 25, 44, seith gelfydyt seven

arts RB. II. 200, seith wystyl seven hostages RB.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6910) (tudalen 014)

|

14 CONSONANT MUTATIONS [

16.

II. 327. But usually without lenation seith cantref, seith cuppyt seven

cubits , seith cant seven hundred, seith punt seven pounds, seith meib seven

sons.

wyth eight: wyth drawst eight beams RB. m, 21, wyth gant eight hundred RB.

II. 386, but wyth cant 39, 40, 230, 257, 258, 385, wyth temyl eight temples

101, wyth tywyssawc eight chiefs 14.

naw nine. After this lenation is occasionally found, e.g. naw rad nine ranks

LA. 17.

mil thousand: mil verthyr a thousand martyrs RB. II. 199.

10. In pumwryr five men, seith wyr seven men, nawwyr nine men, canwr a

hundred men, there seems to be composition.

(/3) After ordinal numbers.

After the feminine ordinals from three onwards there is lenation, e.g. y

dryded geinc the third branch, y seithvet vlwydyn the seventh year, yr

vgeinuet vlwydyn the twentieth year.

11. --The same rule seems to hold with eil other, second, e.g. yr eil

marchawc the second horseman, but yr eil vlwydyn the second year, and with

neill one of two, e.g. y neill troet the one foot, but y neill law the one

hand.

(f) After the pronoun.

(a) After the possessives dy thy and y his, e.g. dy davawt thy tongue, ath lu

and thy host y benn his head, ae rud and his cheek.

(/3) After interrogatives, e.g. pa le, py le where? pa beth what thing?

(y) In apposition, e.g. ynteu Bwyll he Pwyll, hitheu wreic Teirnon she the

wife of Teirnon; ef Vanawydan he Manawydan; on hachaws ni bechaduryeit

because of us sinners.

(g) After the verb.

(a) After the verb lenation is found not only of the object but also of the

subject, whether the verb immediately precedes the lenated form or is

separated from it, e.g. mi a wnn gyghor da / know good counsel, y gwelynt

uarchawc they saw a horseman, ny mynnei Gaswallawn y lad ynteu Caswallawn did

not desire to slay him. The proportion of lenation to non-lenation differs

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6911) (tudalen 015)

|

16.] CONSONANT MUTATIONS.

15

in different parts of the verb. After certain parts of the verb lenation is

absent or exceptional. Such are 3 sg. and 3 pi. pres. ind. act., 3 sg. pres. subj.

act. and the passive forms. After the 3 sg. of the pret. ind. act.

non-lenation of the subject is the rule; in RB. lenation of the object is

occasionally found when it directly follows the verb, e.g. y kavas Uendigeit

Uran he found Bendigeit Vran, frequently when the subject precedes it, e.g. y

lladawd Peredur wyr yr iarll Peredur slew the earl's men.

(P) After most of the forms of the verb "to be" lenation is found,

most consistently in the predicate from its close connexion with the verb,

but also in the subject whether it follows the verb immediately or is

separated from it, e.g. ot wyt uorwyn if thou art a maid, yd ym drist ni we

are sad, yssyd urenhin who is king, yssit le there is a place, nyt oed Uwy //

was not greater, oedynt gystal they were as good, mi a uydaf borthawr / am

gatekeeper, ni a vydwn gyuarwyd we will be guides, ny bydei vyw he was not

alive, y bydynt barawt they should be ready, ny buost gyvartal thou hast not

been just, tra uu vyw while she lived, pan imant veirw whe?i they were dead,

buassei oreu it would have been best, byd lawenach be more joyous, bit bont

let him be a bridge, bydwch gedymdeithon be ye comrades, tra vwyf vyw while 1

live, tra vych vyw while thou livest, tra vom vyw while we live, mal na bont

ueichawc so that they may not be pregnant, pei bewn urathedic if I were

wounded, a vei vawr which should be great, gwedy y beym uedw after we were

intoxicated, nyt DCS blant there is no offspring, budugawl oed Gei Kei was

gifted, y hwnnw y bu uab to him there was a son, cy t bei lawer o geiryd

though there were many cities, nyt oes in gyghor we have no counsel, oed well

ytti geisaw *'/ were better for thee to seek, tost vu gantaw welet it pained

him to see. There is, however, no lenation after ys, e.g. ys gwir it is true (unless

the subject be separated, e.g. kanys gwell genthi gyscu since she prefers to

sleep]; after nyt, nat, neut, e.g. nyt llei is not less, neut marw he is

dead; after OS, e.g. OS gwr if he is a man; after ae e.g. ae gwell is it

better 1 after yw, e.g. pan yw Peredur that it is Peredur (unless the subject

be

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6912) (tudalen 016)

|

i6/ CONSONANT MUTATIONS.

[ 16.

separated, e.g. hawd yw gennyf gaffel / think it easy to get); after yttiw,

e.g. a yttiw Kei yn llys Arthur is Kei in Arthur's court 1 after mae, e.g. y

mae llech there is a flagstone (unless the subject be separated, e.g. y mae

yma uorwyn there is here a maiden); after maent, e.g. y maent perchen there

are owners; after byd, e.g. ny byd gwell it will not be better (unless the

subject be separated, e.g. or byd gwell genwch bresswylaw if ye think it

better to dwell}; after boet, e.g. poet kyvlawn dy rat titheu may thy

prosperity be complete; after bo, e.g. pan UO parawt when it is ready (unless

the subject be separated, e.g. pan uo amser in uynet when it is time for us

to go).

(h) In adverbs and adverbial phrases.

In the interior of a sentence the initial consonant of an adverb or an

adverbial phrase is often lenated, e.g. nyth elwir bellach byth yn vorwyn

thou shalt never more be called a maiden, ny orffowysaf vyth / will never

rest, pan daeth y paganyeit gyntaf y Iwerdon when the pagans came first to

Ireland, bydwch yma vlwydyn y dyd hediw be ye here a year to-day, bu farw

.... vis whefrawr she died in the month of February, pebyllaw a oruc lawer O

dydyeu he encamped many days. In the same way lenation is found in

preposition and suffixed pronoun, e.g. ny eill neb vynet drwydi no one can go

through it, a gymero yr ergit drossof i who shall take the blow in my stead,

hir uu gennyf i y nos honno that night seemed long to me.

NOTE 12. In origin this is only a special case of post-verbal lenation, like

the corresponding change in Irish, for which see Federsen, KZ. xxxv. 332 sq.

NOTE (ISJ Lenation is found of the initial consonants of some

weakening here, however, seems to be that the words are pretonic.

(i) After the prepositions am, ar, att, can, heb, o (a), tan, tros, trwy,

uch, wrth, y, and frequently after the nominal preposition hyt, e.g. am

betheu about things; ar vrys in haste; att Bwyll to Pwyll; gan bawb with

every one; heb vwyt without food; o gerd of music; dan brenn under a tree;

dros

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6913) (tudalen 017)

|

17.] CONSONANT MUTATIONS.

17

vor across the sea] trwy lewenyd through joy; uch benn above; wrth Gynan to

Cynan; y vynyd upwards; hyt galan Mei till the first of May.

(k) After a negative in phrases like na wir it is not true RB. 105; na well

it is not better RB. 61.

(1) After mor how, so and neu or, e.g. mor druan how wretched; neu vuelyn or

horn.

(m) After interjections.

(a) The vocative is lenated after a, ha, oia, och, ub e.g. a vorwyn O maiden;

oia wr hoi man; och Ereint alas! Gereint; ub wyr alack! men. But without any

preceding particle lenation of the vocative is found, e.g. dos vorwyn go,

maiden.

(/?) After llyma, llyna, and nachaf, e.g. llyma luossogrwyd yn ymlit see!

there is a host following RB. II. 302; llyna uedru yn drwc there is bad

behaviour; nachaf uarchawc yn dyuot behold! a horseman was coming.

B. LENATION OF THE PRONOUN. 17. The pronoun is lenated:

(a) As subject or object, or emphasizing an infixed or suffixed pronoun or

possessive adjective, e.g. elwyf ui / might go, gallaf i / can, ny buum drwc

i / was not evil, y rodaf inneu / will give, arhowch uiui wait for me, na

chabla di uiui do not blame me, nyt atwaenwn i didi / did not recognise thee,

ath gud ditheu which hides thee, ohonaf i, ohonaf inneu by me, vy ysgwyd i my

shield, dy grogi di thy hanging, dy lad ditheu thy slaying.

NOTE 1. But after final t t is usual, e,g. y rodeist ti thou hast given, gan

dy genyat ti with thy leave, dy vot titheu thy being.

(b) Sometimes in apposition, e.g. ni a awn ui a thi we will go, I and thou,

keisswn ninneu ui a thi let us seek, I and thou.

(c) After other lenating words, e.g. gwae vi woe to me, neu vinneu or I, neu

ditheu or thou.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6914) (tudalen 018)

|

i8 CONSONANT MUTATIONS. [

18.

C. LENATION OF THE VERB.

18. The verb is lenated:

(a) After infixed pronoun of sg. 2, e.g. yth elwir thou art called.

(b) After relative a, e.g. govyn a oruc he asked.

(c) After the interrogative pa, py, e.g. hyt na wydat pa (or py) wnaei so

that she did not know what she should do; py liwy di why dost thou colour?

(d) When the copula follows the predicate ( 159), e.g. llawen UU y uorwyn the

maiden was glad.

(e) After "the verbal particle yt ( pi note 2) in the older language,

e.g. yt gaffei he should get.

(f) After the verbal particle ry (but cf. 21 note), e.g. ry geveis / have

got. Similarly after neur ( 95 note), e.g. neur gavas he has got.

(g) After the interrogative a, e.g. a bery di wilt thou effect?

(h) After the conjunctions pan, tra, yny, e.g. pan golles when he lost, tra

barhaawd while it lasted, tra vwyf as long as I am, yny glyw till he hears,

yny welas till he saw, yny vyd till he is.

(i) After the negatives ny (including ony, pony) and na (with the exception

of the tenues 2ie), e.g. ny allaf I cannot, ny ladaf / will not slay, kany

vynny since thou dost not desire, pony wydut ti didst thou not know? na ovyn

di do not ask, Duw a wyr na ladaf i God knows that I will not slay.

NOTE. But after ny, na the rule of lenation is not absolute. In partic- ular

initial m is commonly unchanged, e.g. ny mynnaf / do not desire, hyt nc.

mynnei so that he did not desire. Further, initial b of forms of bot to be is

commonly unlenated, e.g. ny bu gystal it was not so good; a wypo na bo rniui

who shall know that it is not I. But in the imperative lenation seems to be

the rule, e.g. na uit amgeled genii well be not troubled. Non- lenation after

ny comes from the ok! non-relative forms ( 21 note). Na originally ended in a

consonant (nac), so that after it the lenation is irregular; so far as it

lenates it has followed the analogy of ny.

Nasal Mutation.

19. Nasal mutation is very irregularly written in Mid.W.MSS. The mutation of

nc is expressed by gk or gh, the mutation of nt

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6915) (tudalen 019)

|

2i.] CONSONANT MUTATIONS.

19

commonly by nt, rarely by nh, the mutation of mp commonly by mp, sometimes by

mph or mh. The mutation of ng is expressed by gg or ngg, the mutation of nd,

nb by n or nd, and m or mb.

20. Nasal mutation is found:

(a) After vyn my, e.g. vygkynghor, vyghynghor my counsel, vyntat, vynhat my

father, vympenn, vymphen, vymhen my head, vyggwreic (gwreic) my wife,

vynggwely my bed, vynyvot, vyndyvot my coming, vymaraf (baraf) my beard.

(b) After yn in, into, e.g. ygkarchar, ygharchar in prison, ymperved,

ymherved in the centre, ymhoen (poen) in punish- ment; yn diwed (=yn niwed)

in the end; ymbwyt, ymwyt (bwyt) into food.

(c) In certain phrases after numerals (chiefly with blyned years and dieu,

diwarnawt days), e.g. pump mlyned five years, chwech mlyned RB. II. 397 (more

usually chwe blyned) six years, seith mlyned seven years, wyth mlyned eight

years, naw mlyned nine years, naw nieu nine days, deng mlyned ten years, dec

nieu ten days, deudec niwarnawt twelve days, pymtheng mlyned fifteen years,

ugein mlyned twenty years, deugeint mlyned forty years, cant mlyned a hundred

years, can mu a hundred kine, trychan mu three hundred kine.

NOTE. This usage started from those numerals which in Old Celtic ended in n:

seith (cf. Ir. secht n-, Lat. septem; final m in Celtic became n), naw (cf.

Ir. noi n-, Lat. novem), dec (cf. Ir. deich n-, Lat. decem), cant (cf. Ir.

cet n-, Lat. centum).

Spirant Mutation.

21. This is found:

(a) After the numerals tri three and chwe(ch) six, e.g. tri chantref three

cantreds, tri pheth three things, chwe thorth six loaves.

(b) After y her, e.g. y chlust her ear, y throet her foot, y phenn her head.

(c) After the prepositions ac, a with, tra beyond, e.g. a chledyf with a

sword, a thi with thee, tra thonn beyond wave.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6916) (tudalen 020)

|

20 CONSONANT MUTATIONS.

[22.

(d) After the conjunctions a(c) and, no(c) than, o if, e.g. mam a that father

and mother, tract a phenn feet and head; gwaeth no chynt worse than before \

o chigleu if he has heard.

NOTE 1. After kwt where spirant change is found: cv threwna where it settles

BB. 44 b , but kwt gaffei (caffei) where he should get WB. 453; cf. cud vit

BB. 44 b , cwd uyd where it will be FB. 146.

(e) After the negatives ny and na(c), e.g. ny chysgaf / will not sleep, ny

thyrr does not break, ny phryn does not buy; na chwsc do not sleep, na

thorraf that I do not break, na marchawc na phedestyr neither horseman nor

footman.

NOTE. 2. But in the early poetry ny produces the spirant change only when it

is non-relative; when it is relative a following c, t, or p is lenated, e.g.

ny char he does not love, but ny gar who does not love. In the early poetry there

is the same difference of treatment after the verbal particle ry, e.g. ry

char as has loved, ry garas who has loved. This distinction between

non-relative and relative forms must have extended to all consonants capable

of mutation, but in the case of the other consonants confusion set in

earlier. In later Mid. W. after ny the non-relative form has been generalised

in the case of words beginning with c, t, p, the relative form, with certain

exceptions, in the case of words beginning with other mutable consonants (cf.

18 i). After ry the relative form was generalised. For further details see

Eriu III. pp. 20 sq.

h in Sentence Construction.

22. After certain words h appears before a following word beginning with a

vowel.

(a) After the infixed and the possessive pronoun m, e.g. am h- ymlityassant

ivho followed me, om h-anvod against my will.

(b) After the infixed pronoun e, e.g. ae h-arganvu who perceived him.

(c) After y tier, e.g. y h-enw her name.

NOTE. In Irish also h appears after a her, e.g. a h-ainm her name. The Irish

and Welsh h here comes from the original final s of the possessive.

(d) After an our, e.g. an h-arueu our arms.

(e) Aften eu, y their, e.g. eil h-arueu their arms.

(f) After ar before ugeint twenty, e.g. un ar h-ugeint twenty one.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6917) (tudalen 021)

|

24.] THE ARTICLE. 21

THE ARTICLE.

. In O.W. the article is ir throughout, e.g. ir pimphet eterin the fifth

bird, dir finnaun to the fountain. In Mid.W. yr remains before vowels and h,

e.g. yr amser the time, yr alanas (from galanas) the bloodfine, yr henwr the

old man; before other consonants except y it becomes y, e.g. y bwyt the food,

y wreic (from gwreic) the woman; before y the usage varies, e.g. yr iarll or

y iarll the carl. But if the article be fused together with a preceding

conjunction or preposition, or if the y be elided after a preceding vowel,

then 'r remains, e.g. y nef ar dayar heaven and earth, yn gyuagos yr gaer near

to the city, gwiryon yw'r liorwyn ohonof i the maiden is innocent as regards

me.

SYNTAX OF THE ARTICLE.

24. (a) In addition to its use before common nouns the article appears

regularly before the names of certain countries, such as yr Affrica Africa,

yr Asia Asia, yr Alban Scotland, yr Almaen Germany, yr Eidal Italy, yr Yspaen

Spain, e.g. vn yw yr Asia, deu yw yr Affrica, tri yw Europa Asia is one,

Africa is two, Europe is three FB. 216. Occasionally the article appears

before names of persons, e.g. yr Beli mawr ( = y Beli uawr WB. 191) to Beli

the Great RB. 93, 2; mwyhaf oe vrodyr y karei Lud y Lleuelys Llud loved

Llevelys more than any of his other brothers ib.

(b) The article is not used before a noun followed by a dependent genitive,

e.g. gwyr ynys y kedyrn the men of the island of the strong, unless it be

accompanied by a demonstrative pronoun, e.g or meint gwyrtheu hwnnw from that

amount of miracles, or unless the genitive be the equivalent of an adjective,

e.g. y werin eur the golden chessmen, y moch coet the wild pigs (lit. the

pigs of the wood], y peir dateni the cauldron of rebirth, the regenerative

cauldron.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6918) (tudalen 022)

|

22 THE NOUN. [25.

THE NOUN. NUMBERS AND CASES.

25. In Welsh the old Celtic declension is completely broken down. Of the

three genders the neuter has been lost. The dual, which, as in Irish, is

always preceded by the numeral for two, in some classes of nouns would

phonetically have fallen together with the singular; in Welsh this has been

generalised so that the dual (apart from forms like deu ychen two oxen}

coincides in form with the singular; a trace of the dual inflection remains

in the lenation of a following adjective, e.g. deu vul gadarn (from cadarn)

two strong mules, deu vilgi vronwynnion vrychion two white breasted brindled

greyhounds. In the regular inflexion there remains only one case for each

number; in the singular this corresponds some- times to the old nominative,

e.g. car friend '= Ir. carae, sometimes to the form of the oblique cases,

e.g. breuant windpipe = Ir. brage, g. bragat; a few traces of lost cases

still survive in phrases, e.g. meudwy hermit (lit. servant of God), where dwy

is the genitive of duw; erbynn against ( = Ir. ar chiunn), where pynn (from

*pendl, from *pendu) is the dative of perm head; peunyd every day, peunoeth

every night, where peun-, which in O.W. would be *poun-, comes from *popn-,

the old accusative singular of pob every.

SYNTAX OF THE CASES.

26. As in Irish, the nominative may stand absolutely at the beginning of the

sentence to introduce the subject of discourse, e.g. y wreic honn ym penn

pythewnos a mis y byd beichogi idi, lit. this woman, at the end of a

fortnight and a month there will be conception to her. In prose the genitive

follows the noun on which it depends, e.g. enw y mab the name of the son; in

poetry it may precede, e.g. byt lywaydur = llywaydur byt the ruler of the

world; sometimes, as in Irish, it is used after an adjective meaning with

respect to a thing, e.g. ny bydy anuodlawn y phryt thou wilt not

THE NOUN.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6919) (tudalen 023)

|

23

be displeased with her form. The accusative can be recognised only from the

construction; in poetry the accusative of a place-name is common after verbs

of motion, e.g. dywed y down Arwystli say that we will come to Arwystli MA.

192*.

FORMATION OF THE PLURAL.

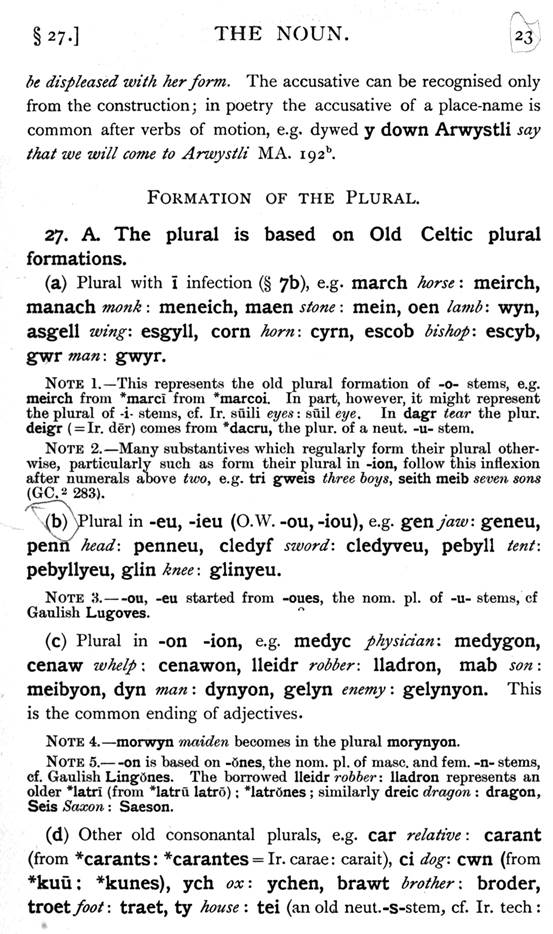

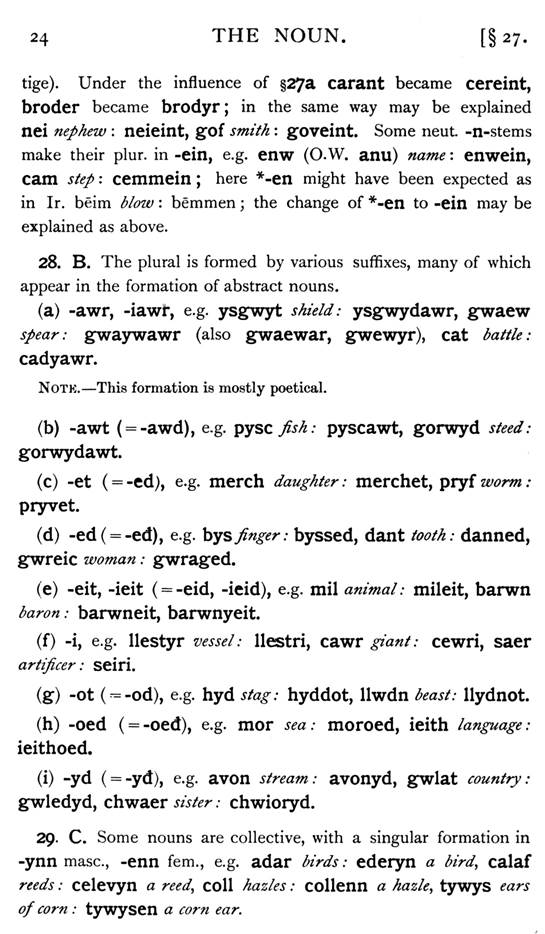

27. A. The plural is based on Old Celtic plural formations.

(a) Plural with I infection ( 7b), e.g. march horse: meirch, manach monk:

meneich, maen stone: mein, oen lamb: wyn, asgell wing: esgyll, corn horn:

cyrn, escob bishop: escyb,

gwr man: gwyr.

NOTE 1. This represents the old plural formation of -o- stems, e.g. meirch

from *marci from *marcoi. In part, however, it might represent the plural of

-i- steins, cf. Ir. suili eyes: suil eye. In dagr tear the plur. deigr ( =

Ir. der) comes from *dacru, the plur. of a neut. -u- stem.

NOTE 2. Many substantives which regularly form their plural other- wise,

particularly such as form their plural in -ion, follow this inflexion after

numerals above two, e.g. tri gweis three boys, seith meib seven sons (GC^

283).

(b) Plural in -eu, -ieu (O.W. -ou, -iou), e.g. gen jaw: geneu, penn head:

penneu, cledyf sword: cledyveu, pebyll tent: pebyllyeu, glin knee: glinyeu.

NOTE 3. ou, -eu started from -oues, the nom. pi. of -u- stems, cf Gaulish

Lugoves.

(c) Plural in -on -ion, e.g. medyc physician: medygon, cenaw whelp: cenawon,

lleidr robber: lladron, mab son: meibyon, dyn man: dynyon, gelyn enemy:

gelynyon. This is the common ending of adjectives.

NOTE 4. morwyn maiden becomes in the plural morynyon.

NOTE 5. on is based on -Ones, the nom. pi. of masc. and fern, -n- stems,

cf. Gaulish Ling5nes. The borrowed lleidr robber: lladron represents an older

*latri (from *latru latro); *latrones; similarly dreic dragon: dragon, Seis

Saxon: Saeson.

(d) Other old consonantal plurals, e.g. car relative: carant (from *carants:

*carantes = Ir. carae: carait), ci dog: cwn (from *kuu: *kunes), ych ox:

ychen, brawt brother: broder, troet/00/: tract, ty house: tei (an old

neut.-s-stem, cf. Ir. tech:

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6920) (tudalen 024)

|

24 THE NOUN. [27.

tige). Under the influence of 27a carant became cereint, broder became

brodyr; in the same way may be explained nei nephew: neieint, gof smith:

goveint. Some neut -n-stems make their plur. in -ein, e.g. enw (O.W. anu)

name: enwein, cam step: cemmein; here *-en might have been expected as in Ir.

beim blow: bemmen; the change of *-en to -ein may be explained as above.

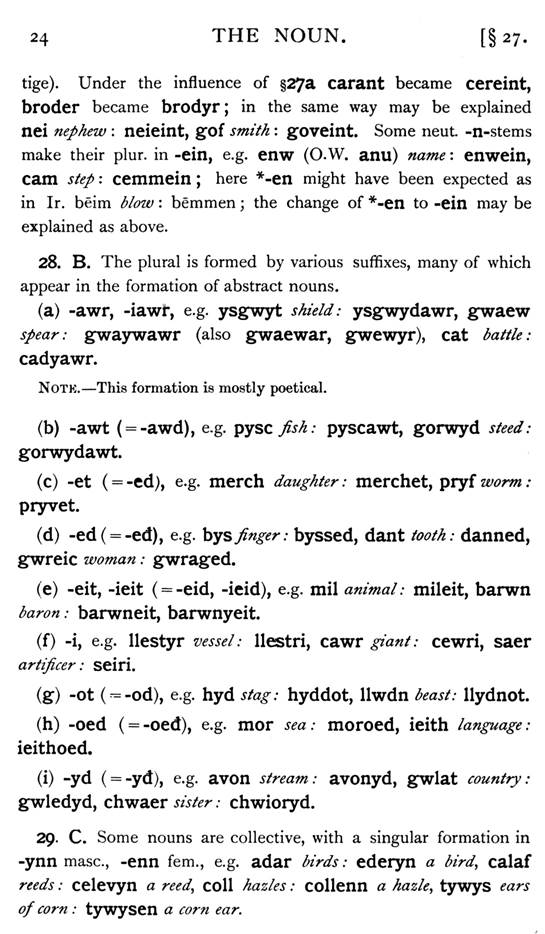

28. B. The plural is formed by various suffixes, many of which appear in the

formation of abstract nouns.

(a) -awr, -iawr, e.g. ysgwyt shield: ysgwydawr, gwaew spear: gwaywawr (also

gwaewar, gwewyr), cat battle: cadyawr.

NOTE. This formation is mostly poetical.

(b) -awt ( = -awd), e.g. pysc/^; pyscawt, gorwyd steed: gorwydawt.

(c) -et ( = -ed), e.g. merch daughter: merchet, pryf worm: pryvet.

(d) -ed( = -ed), e.g. bysfager: byssed, dant tooth: danned, gwreic woman:

gwraged.

(e) -eit, -ieit ( = -eid, -ieid), e.g. mil animal: mileit, barwn baron:

barwneit, barwnyeit.

(f) -i, e.g. llestyr vessel: llestri, cawr giant: cewri, saer artificer:

seiri.

(g) -ot ( = -od), e.g. hyd stag: hyddot, llwdn beast: llydnot.

(h) -oed ( = -oed), e.g. mor sea: moroed, ieith language: ieithoed.

(i) -yd ( = -yd), e.g. avon stream: avonyd, gwlat country: gwledyd, chwaer

sister: chwioryd.

29. C. Some nouns are collective, with a singular formation in -ynn masc.,

-enn fern., e.g. adar birds: ederyn a bird, calaf reeds: celevyn a reed, coll

hazles: collenn a hazle, tywys ears of corn: tywysen a corn ear.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B6921) (tudalen 025)

|

32.]

THE ADJECTIVE.

THE ADJECTIVE.

GENDER.

30. There is a special form of the feminine only in the singular, and only in

adjectives containing y, w, which in the feminine became e, O ( 7a), e.g.

gwynn white: gwen, melyn yellow: melen, bychan small: bechan, brith

variegated: breith, \\vrmmfare: llomm, crwnn round: cronn.

In the singular the adjective is lenated after a feminine noun, e.g. gwreic

dec a beautiful woman ( l6ba); in the plural there is no lenation.

NOTE. In the Celtic adjective there were -0- stems, -i- stems and -u- stems,

which are distinguishable in O.Ir., e.g. troram heavy from *trummo-s, cruind

round from *crundi-s, and il much from *pelu-s. Only the -o- stems had a

fern, in -a, so that only in these is the Welsh change of vowel

etymologically justified. But in Welsh, after the loss of final syllables,

the three classes were indistinguishable in the masculine, and the vowel-

change in the feminine spread analogically from the -o- stems to the others,

e.g. crwnn from *crundis formed a feminine cronn after the analogy of tromm:

trwmm, etc.

FORMATION OF THE PLURAL.

31. The plural is formed:

(a) By change of vowel e.g. bychan small: bychein, ieuanc young: ieueinc.

(b) By adding -on, e.g. dll black: duon, gwineu bay: gwineuon.

(c) By adding -yon (its usual formation), e.g. gwynn white: gwynnyon, melyn

yellow: melynyon.

CONCORD. Gender.

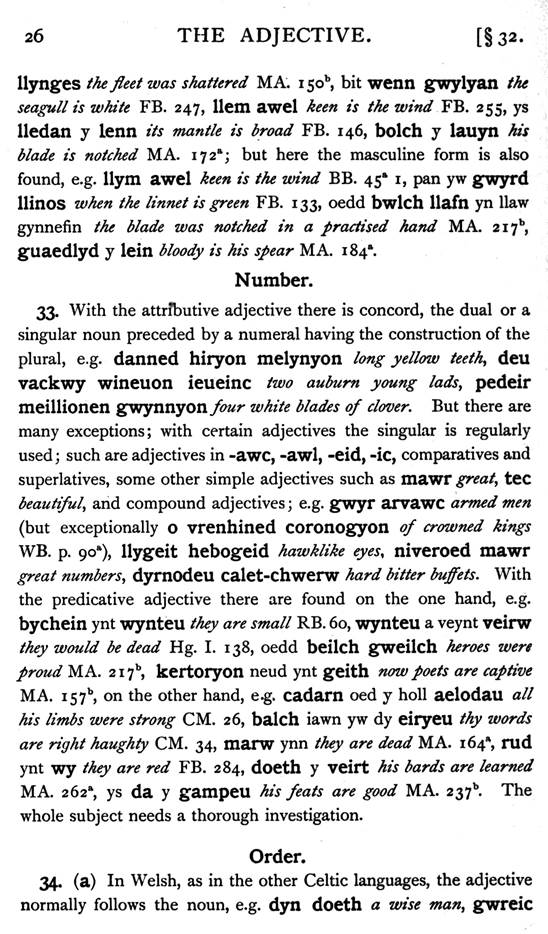

32. In the singular the attributive adjective agrees in gender with its noun,

e.g. gwas melyn an auburn lad, morwyn benngrech velen a curly-headed auburn

maiden. With the predicative adjective agreement is also found, e.g. un

ohonunt oed amdrom one of them was very heavy RB. 54, 17, oed amdroch

|

|

|

|

|

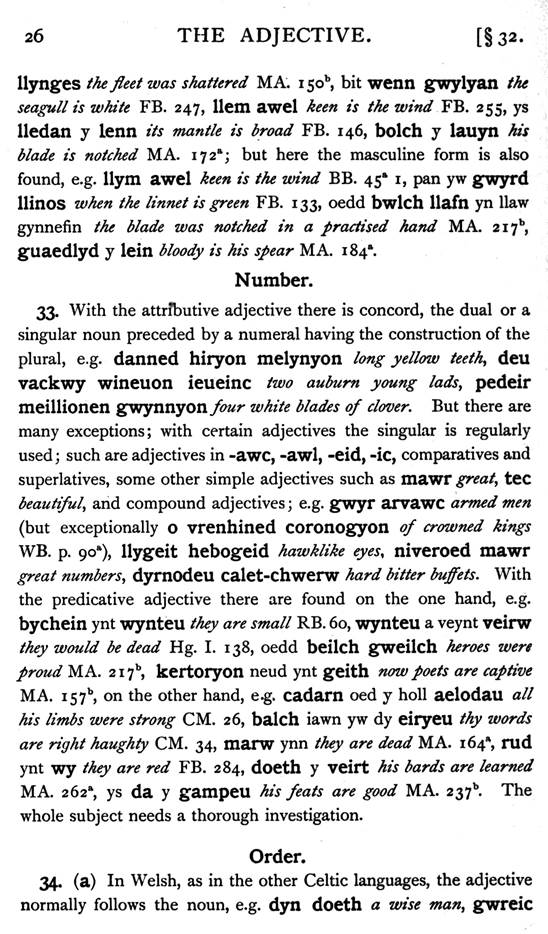

(delwedd B6922) (tudalen 026)

|

26 THE ADJECTIVE. [32.

llynges the fleet was shattered MA. i5o b , bit wenn gwylyan the seagull is

white FB. 247, Hem awel keen is the wind FB. 255, ys lledan y lenn its mantle

is broad FB. 146, bolch y lauyn his blade is notched MA. 172*; but here the

masculine form is also found, e.g. llym awel keen is the wind BB. 45* i, pan

yw gwyrd llinos when the linnet is green FB. 133, oedd bwlch llafn yn Haw

gynnefin the blade was notched in a practised hand MA. 2i7 b , guaedlyd y

lein bloody is his spear MA. 184*.

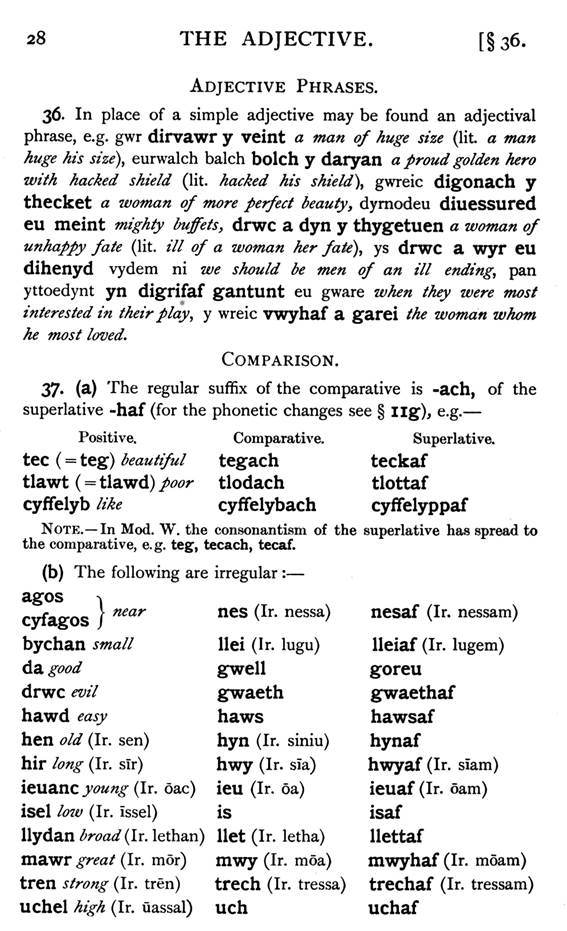

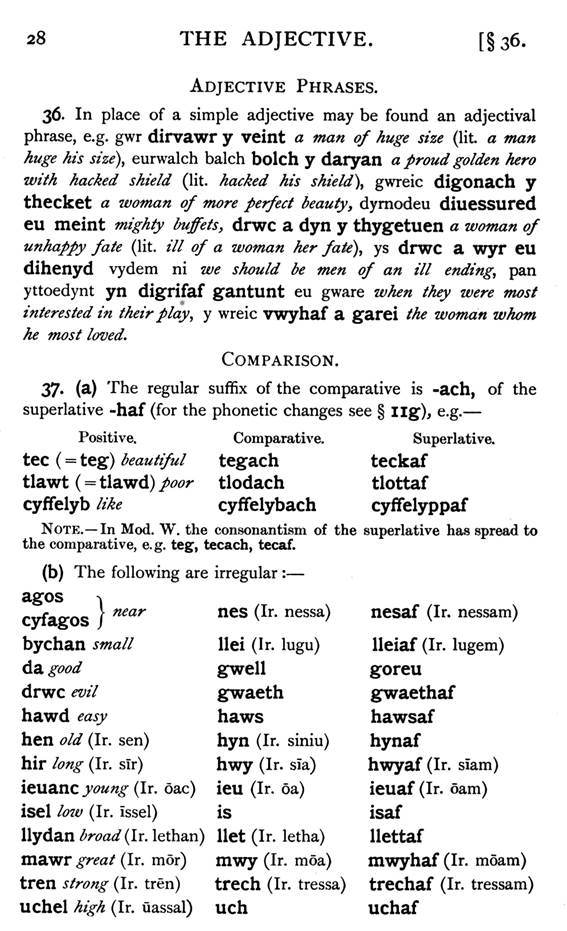

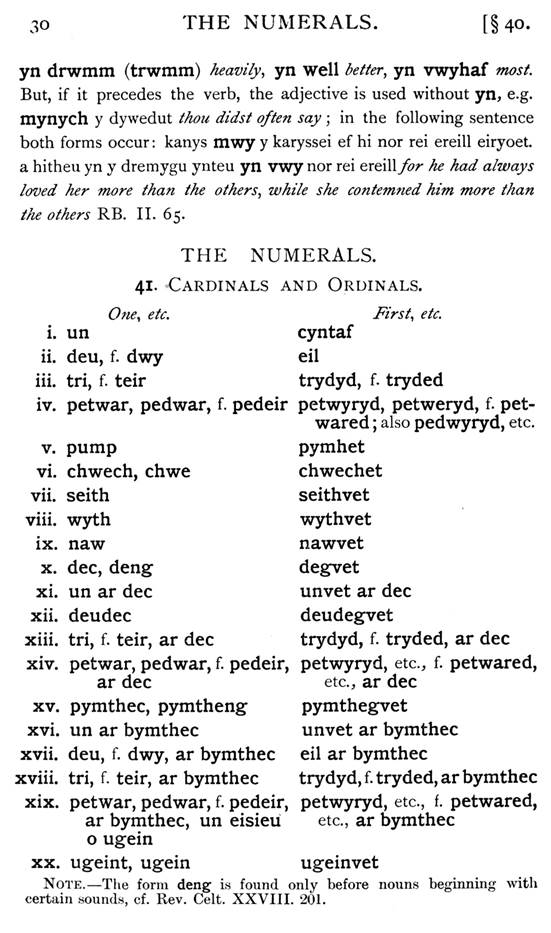

Number.

33. With the attributive adjective there is concord, the dual or a singular

noun preceded by a numeral having the construction of the plural, e.g. danned

hiryon melynyon long yellow teeth, deu vackwy wineuon ieueinc two auburn