kimkat2123k The Philology of the English Tongue. John

Earle, M.A. Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Oxford. Third

Edition. 1879.

15-11-2018

●

kimkat0001 Yr Hafan www.kimkat.org

● ●

kimkat2001k Y Fynedfa Gymraeg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwefan/gwefan_arweinlen_2001k.htm

● ● ●

kimkat0960k Mynegai ir holl destunau yn y wefan hon www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_llyfrgell/testunau_i_gyd_cyfeirddalen_4001k.htm

● ● ● ●

kimkat0960k Mynegai ir testunau Cymraeg yn y wefan hon www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/sion_prys_mynegai_0960k.htm

● ● ● ● ●

kimkat2121k The Philology of the English Tongue / Astudiaeith Gymharol or

Iaith Saesneg 1879 - Y Gyfeirddalen

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/testun-246_philology-english-tongue_earle_1879_y-gyfeirddalen_2121k.htm

● ● ● ● ● ●

kimkat2123k y tudalen hwn

|

|

|

Gwefan Cymru-Catalonia |

|

.

![]() https://translate.google.com/

https://translate.google.com/

(Cymraeg,

catalΰ, English, euskara, Gΰidhlig, Gaeilge, Frysk, Deutsch, Nederlands,

franηais, galego, etc)

...

llythrennau duon = testun wedi ei gywiro

llythrennau gwyrddion = testun heb ei gywiro

.....

|

|

|

|

|

I50 II. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. accident, quhither quho, quhen, quhat, etc., should be

symbolised with 7 or w, a hoat disputation betuene him and me. After manie

conflictes (for we oft encountered), we met be chance, in the citie of Baeth,

with a Doctour of divinitie of both our acquentance. He invited us to denner.

At table my antagonist, to bring the question on foot amangs his awn

condisciples, began that I was becum an heretick, and the doctour spering

how, ansuered that I denyed quho to be spelled with a w, but with qu. Be

quhat reason? quod the doctour. Here, I beginning to lay my grundes of

labial, dental, and guttural soundes and symboles, he snapped me on this hand

and he on that, that the doctour had mikle a doe to win me roome for a

syllogisme. Then (said I) a labial letter can not svmboliz a guttural syllab.

But w is a labial letter, quho a guttural sound. And therfoer w can not

symboliz quho, nor noe syllab of that nature. Here the doctour staying them

again (for al barked at ones), the proposition, said he, I understand; the

assumption is Scottish, and the conclusion false. Quherat al laughed, as if I

had bene dryven from all replye, and I fretted to see a frivolouse jest goe

for a solid ansuer. Of the Orthographie, &c, p. 18. The Scotchman was

right. And the Southrons might thank the Scotch for having preserved a fine

trait of English pronunciation, yea they might even endeavour by culture and

education to recover the true and masculine utterance of what, which, where,

when, while. 152. To the same cause must be attributed the motive for

changing the spelling of liht, miht, nihl, siht, to light, might, night,

sight. Probably the g was prefixed to the h in order to insist on the h being

uttered as a guttural. If so, it has failed. The guttural writing remains as

a historical monument, but the sound is no longer heard except in Scotland

and the conterminous parts of England. After gh had become quiescent, it was

liable to be employed carelessly or arbitrarily. For example, Spenser wrote

the adjective white in the following unrecognisable manner, whight: His

Belphcebe was clad All in a silken camus lilly whight. Faery Queene, ii. 3.

26. In Ralegh's letters we repeatedly find wright write; so also spright was

written instead of sprite; and although it is |

|

|

|

|

|

SAXON WORDS. 151 now obsolete,

yet its derivative sprightly is still in use. Spight for spite, in Spenser,

quoted below (156), may seem to have more right to the guttural, as it is

from despectare. 153. Likewise Saxon H-flnal has become gh, as burh burgh and

borough, sloh slough, f>ruh trough. But the case of ugh must be noticed

apart. Sometimes it sounds like simple u or w; as in plough, through, daughter,

slaughter. In other cases it sounds like_/*; as cough, enough, rough,

laughter. In dough, though it is quiescent. The same variety occurs in local

and family names. In some parts of England the name Waugh is pronounced as

Waw, and in others as Waff. Opinions differ about the f sound: chough, cough,

enough, laughter, rough, slough (of a snake), tough, trough. Some have

thought that this pronunciation may have risen from interpreting the u as f,

as lieutenant becomes 'leftenant.' But this hardly gives an adequate

explanation, inasmuch as it applies only within the pale of literature,

whereas some of the strongest examples rise outside. Indeed it would seem

that there is hardly any of these ugh words, that has not had the f sound at

some time or in some locality. The 1 Northern Farmer ' says thru/ for

through; and in Mrs. Trimmer's Robins, chap, vi., though receives a like

treatment; for Joe the gardener says, ' No, Miss Harriet; but I have

something to tell you that will please you as much as ihdf I had 1 / The

following quotation from Surrey seems to indicate that taught in his time

might be pronounced as ' toft ': Farewell! thou hast me taught, To think me

not the first That love hath set aloft, And casten in the dust. 1 This will

not be found in all editions, because such rude things are deemed

objectionable by modern educationists; and Mrs. Trimmer is expurgated. |

|

|

|

|

|

1$2 II. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. At Ilkley, near Leeds, slaughter may be heard pronounced like laughter;

and John Bunyan could pronounce daughter as ' dafter ': Despondency, good

man, is coming after, And so is also Much-afraid, his daughter. With these

facts before us, it seems plain we must acknowledge that the gh itself does

sound as f\ the guttural has undergone transition to the labial. There is one

word of this group whose pronunciation is not yet uniformly established (in

the public reading of Scripture), and that is the word draught. The

colloquial pronunciation is now ' draft,' but in Dryden we find the other

sound: Better to hunt the fields for health unbought, Than fee the doctor

for a nauseous draught. The gh with which we have been now dealing is a

domestic product: there is yet another gh, and the notice of it shall close

this division, which has been occupied with the modifications that befell the

old Saxon spelling. Initial gh as equivalent to g (hard) or French gu, is an

Italian affectation, and for the most part a toy of the Elizabethan period:

a-ghast, ghastly, gherkin, ghost (gost in Chaucer, Prol. 205). The word which

we now write guess is in Spenser ghess. Orthography of the French Element.

154. If we now leave the Saxon and notice the French words that entered

largely into our language in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, there are

two general observations to be made concerning them: 1. They take their

orthography from the French of the time, and therefore the Old French is

their standard of comparison. 2. They were at first pronounced as French

words; and although the ori |

|

|

|

|

|

FRENCH WORDS. 1 53 ginal

pronunciation was soon impaired, yet a trace of their native sound followed them

for a long time, just as happens in like cases in our own day. The French

accentuation would remain after every other tinge of their origin had faded

out. In course of time they were so completely familiarised that their origin

was' lost sight of, and then they insensibly slid into an English

pronunciation. The spelling would sometimes follow all these changes, but in

other cases the habit of writing was too strongly fixed. The modern French

words bouquet, trait, familiar as they are among us, still keep their French

form and French pronunciation. The Old French word honour appeared in English

as honure in Layamon and then as honour in Chaucer, and in both cases it was

accented after the French manner on the last syllable. But now that the

accent has moved forward to the first syllable, there is a tendency to

abolish the traces of French orthography The adjective hojiourable is

anglicised in the titular use of the word, when it is written Honorable; and

there are some authors who now omit the u in the substantive and adjective

alike, and upon all occasions. The American writers are conspicuous for their

disposition to reject these traces of early French influence. 155. In reading

early English poets, if we wish to catch the music as well as the sense, we must

bear in mind the difference of pronunciation; and that difference is for the

most part a matter of Old French. The tendency of the French nation is the

reverse of ours in the matter of accentuation. They are disposed to throw the

accent on the close of a word; we always try to get it as near the beginning

as possible. There is a large body of French words in our language which have

at length yielded |

|

|

|

|

|

154 n - SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. to the influences by which they are surrounded, and have come

to be pronounced as English-born words. The same words were for centuries

accented in the French manner, and these are especially the ones we ought to

attend to, if we would wish not to stumble at the rhythm of our early poets.

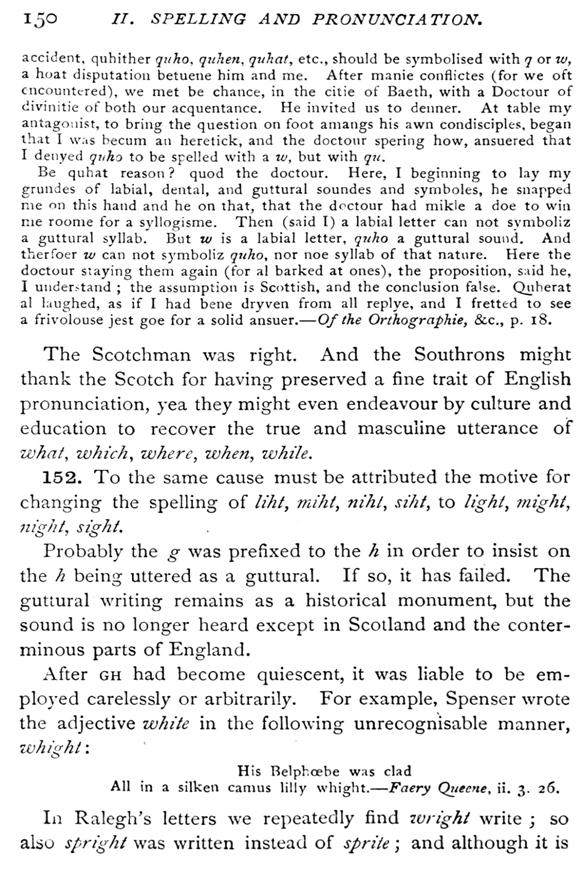

Chaucer has |

|

|

|

|

|

FRENCH WORDS. 1$$ the current

judgment of the polite society of his and of our day. We find it in Shakspeare,

Romeo and Juliet, i. 5: You must contrary me, marry 'tis time. And Spenser,

Faery Queene, ii. 2. 24, where I will quote the whole stave for the sake of

its beauty: As a tall ship tossed in troublous seas (Whom raging windes,

threatning to make the pray Of the rough rockes, doe diversly disease) Meetes

two contrarie billowes by the way, That her on either side doe sore assay,

And boast to swallow her in greedy grave; Shee, scorning both their spigbts,

does make wide way, And, with her brest breaking the fomy wave, Does ride on

both their backs, and faire herself doth save. And Milton in Samson

Agonisles, 972: Fame, if not double-fac'd, is double-mouth'd, And with

contrary blast proclaims most deeds. 157. Although the disposition of our language

is to throw the accent back, yet we are far from having divested ourselves of

words accented on the last syllable. There are a certain number of cases in

which this constitutes a useful distinction, when the same word acts two

parts. Such is the case of humane and human; of august and the month of

August ', which is the selfsame word. Sometimes the accent marks the

distinction between the verb and the noun: thus we say to reb/l, to record)

but a rebel a re'cord. When the lawyers speak of a record (substantively),

they merely preserve the original French pronunciation, and thereby remind us

that the distinction last indicated is a pure English invention. We have many

borrowed words to which we have given a domestic character by setting them to

a music of our own. But independently of the instances in which the accent on

the last syllable is of manifest utility, there are others naturally accented

in the same manner, in which there seems |

|

|

|

|

|

156 U. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. to be no disposition to introduce a change. Examples:

polite, urbane, jocose, divine, complete. 158. In the fourteenth, fifteenth,

and sixteenth centuries, it was a trick and fashion of the times to lengthen

words by the addition of an e, a silent ^-final. A great number of these

final e's have been abolished, others have been utilised, as observed in 159;

but these fashions mostly leave their traces in unconsidered relics. Such is

the e at the end of therefore, which has no use as expressive of sound, and

which exerts a delusive effect on the sense, making the word look as if it

were a compound of fore, like before, instead of with for, which is the fact;

and for this reason some American books now print therefor. 159. In the case

of this ^-subscript, that which had originally been nothing more than a trick

or fashion of the times came to have a definite signification assigned to it.

In the fifteenth century it was a mere Frenchism, a fashion and nothing more.

But by the end of the sixteenth century it came to be regarded as a

grammatical sign that the proper vowel of the syllable was long \ Against

this orthographical idiom the Scotch grammarian, Alexander Hume, who

dedicated his book to King James I, stoutly protested: We use alsoe, almost

at the end of everie word, to wryte an idle e. This sum defend not to be

idle, because it affectes the voual before the consonant, the sound quherof

many tymes alteres the signification; as, hop is altero tantam pede sallare;

hope is sperare: fir, abies; fyre, ignis: a fin, pinna; fine, probatus: bid,

jubere; bide, manere: with many moe. It is true that the sound of the voual

befoer the consonant many tymes doth change the signification; but it is as

untrue that the voual e behind the consonant doth change the sound of the

voual before it. A voual devyded from a voual be a consonant can be noe

possible means return thorough the consonant into the former voual.

Consonantes betuene vouales are lyke partition walles 1 To indicate the

subservient use of this letter, I have (for want of a better expression)

borrowed from a somewhat analogous thing in Greek grammar the term

e-subscript. |

|

|

|

|

|

VARIATIONS, 157 betuen roomes.

Nothing can change the sound of a voual but an other voual coalescing with it

into one sound. . . . To illustrat this be the same exemples, saltare is to

hop; sperare is to hoep; abies is_/fr; ignis fyr; or, if you will.^er: jubere

is bid; manere byd or bied. 0/ the Orthographie, &c, p. 21. 160. The

fifteenth century is the period in which we adopted the French combination gu

to express the retention of the hard G-sound before e or i. Chaucer has

guerdon, which is a French word; but he did not apply this spelling to words

of English origin, such as, guess, guest, guild, guilt. These in Chaucer are

written without the u. Mr. Toulmin Smith spells gild throughout his book

entitled English Gilds. In language we have an abnormal French spelling,

which lost its footing with them, but established itself with us. Here the u

has acquired a consonantal value as a consequence of the orthography. In

Chaucer it is langage, but in the Promptorium (1440) we read 'Langage or

langwage/ (168.) The form of tongue has been altered (119) through French

imitation, probably by the attraction of French la?igue. Divers incidental

variations. 161. Another fashion was the doubling of consonants, as in the

case of ck. Many of these remained to a late date; and there are some few

archaisms of this sort which have only just been disused. Such are poetick,

ascetick, politick, catholick, instead of poetic, ascetic, politic, catholic.

This was the constant orthography of Dr. Johnson: ' The next year (17 13), in

which Cato came upon the stage, was the grand climacteric^ of Addison's

reputation/ When such exuberances are dismissed, it is quite usual to make an

exception in favour of Proper names. There are very good and practical

reasons why these should affect a spelling somewhat removed from the common

habits of the Ian |

|

|

|

|

|

I $8 //. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. guage, and accordingly we find that almost every discarded fashion

of spelling lives on somewhere in Proper names. The orthography of Frederick

has not been reformed, and the ck holds its ground advantageously against the

timidly advancing fashion of writing Frederic. 162. To the same period

belongs the practice of writing double / at the end of such words as

celestially mortall, faithfully eternall, counsell, naturally unequally

wakefull, cruell: also in such words as lilly, 152. It is a relic of this

fashion that we still continue to write till, all, full, instead of til,

al,ful, which were the forms of these words in Saxon. Spenser has an

inclination to put French c for s (132), and y for i, thus bace desyre {Faery

Queene, ii. 3. 23) for base desire. The vacillation between c and s

terminated discriminatively in a few instances. Thus we have prophesy the

verb and prophecy the noun, to practise and a practice. Less established, but

often observed, is the differentiation of license the verb from licence the

substantive, as Licence they mean when they cry Liberty. John Milton,

Sonnet xii. 11; ed. Tonson, 1725. 163. In the sixteenth century there

appeared a fashion of writing certain words with initial sc- which before had

simple s-. It was merely a way of writing the words, and was without any

significance as to the sound. Hence the forms scent, scile, scitualion: and

Saxon siZe became scythe. It probably sprang from the analogy of such Latin

forms as scene, science, sceptre. These cases are to be kept apart from those

of 150. Scent is from the Latin sentire, French senlir, and is written sent

in Spenser, Faery Queene, i. 1. 53. Scile seems to be returning to its

natural orthography of |

|

|

|

|

|

VARIATIONS 159 site, as being

derived from the Latin situs; and we once more write it as did Spenser and

Ben Jonson. But there are still persons of authority who adhere to the

seventeenth-century practice the practice of Fuller, Burnet, and Drayton.

164. In the sixteenth century there/was a great disposition to prefix a w

before certain words beginning with an h or with an r. This seems to have

been due to association. There was in the language an old group of words

beginning with wh and wr; such as, whale, wharf, wheal, what, wheel, when,

where, which, who, whither, wrath, wreak, wrestle, wretch, wright, wrist,

write, wrong, all familiar words, and some of them words of the first

necessity. The contagion of these examples spread to words beginning with h

or r simple, and the movement was perhaps aided in some measure by the desire

to reassert the languishing gutturalism of h and (we may add) of r. This was

the means of engendering some strange forms of orthography, which either

became speedily extinct or maintained an obscure existence. For example, whot

is found instead of hot, as He soone approched, panting, breathlesse, whot,

Faery Queene, ii. 4. 37, and red-whot, iv. 5. 44; whome, instead of home\

wrote instead of root. In Shakspeare, Troylus and Cressida, iii. 3. 23, wrest

most probably belongs here, being an Elizabethan form of rest. In Sir W.

Ralegh's Letters we find wrediness readiness. Ralegh's own name occurs in

contemporary documents as Wrawlegh. The form wrapt, as quoted in 197, belongs

here. Modern writers seem to have decided for rapt: this is the only form in

Tennyson, who has wrapt only in such phrases as ' wrapt in a cloak.' This is

an instance in which it may be doubted whether the word |

|

|

|

|

|

l6o II. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. does not lose a certain poetic haze by being so rigidly

etymologized. In Dean Milman's History of the Jews, ed. 1868, it stands,

'Elijah had been wrapt to heaven in a car of fire/ 165. By this process was

formed the vexed word wretchlessness in the seventeenth Article. To

understand this word, we have only to look at it when divested of its initial

w, as retchlessness; and then, according to principles already defined, to

remember that an ancient Saxon c at the end of a syllable commonly developed

into tch (147); and in this way we get back to the verb to reck, Anglo-Saxon

recan, to care for. So that retch-less-ness is equivalent to

care-nought-state of mind, that is to say, it is much the same thing as '

desperation.' The prefixed w has in this instance proved fatal to the word.

The tch form of this root has fallen out of use, and probably it was the

prefixing of this w that extinguished it. For it had the effect of creating a

confusion between this word and wretch, a word totally distinct, and this is

one of the greatest causes of words dying out, when they clash with others

and promote confusion. We retain the verb to reck, and also reckless and

recklessness, which means the same as wretchlessness. The Bible-translator,

Myles Coverdale 1 spelt r aught (the preterite of reach, and equivalent of

our reached) with a wSpeaking of Adam stretching forth his hand to pick the

forbidden fruit, he says, ■ he wrought life and died the death.' That is to say, he raught, or

snatched at, life. But besides these obscure forms, one at least sprang up

under the same influence, which has retained a place in standard English. The

form whole stood for hole or hale, which sense it bears in the English New

Testament, though 1 Writings 0/ Myles Coverdale, Parker Society, The Old

Faith, p. 17. |

|

|

|

|

|

VARIATIONS. l6l it has since run

off from the sense of hale, sound (integer), into that of complete (totus).

In this case, the language has been accidentally enriched. A new word has

been introduced, and one which has made for itself a place of the first

importance in the language. For the expression the whole has obtained

pronominal value in English. 166. One of the most remarkable instances of

this change (remarkable because it was made in the pronunciation only and not

in the writing of the word) is that of the numeral one. It used to be

pronounced as written, very like the preposition on, a sound naturally

derived from its original form in the Saxon numeral an. But it has now long

been pronounced as wun or won (in Devonshire wonn), and this change may with

probability be placed at the close of the sixteenth century. It was

apparently a west-country habit which got into standard English. In

Somersetshire may be heard ' the wonn en the wother ' for ' the one and the

other.' In the eastern parts of England, and especially in London, it is

well-known vernacular to say un, commonly written y un, as if a w had been

elided; e. g. 'a good 'un.' In Loves Labour's Lost, iv. 2. 80, it is plainly

pronounced on or oon. One of the features of the Dorset dialect is the broad

use of this initial w, both in the first numeral and in other words, such as

woak for oak, wold for old, woofs for oats. John Bloom he wer a jolly soul, A

grinder o' the best o' meal, Bezide a river that did roll, Vrom week to week,

to push his wheel. His flour were all a-meade o' wheat, An' fit vor bread

that vo'k mid eat; Vor he would starve avore he'd cheat. * Tis pure,' woone

woman cried; ' Ay, sure,' woone mwore replied; 'You'll vind it nice. Buy

woonce, buy twice,' Cried worthy Bloom the miller. |

|

|

|

|

|

1 62 II. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. The same worthy miller sitting in his oaken chair is described

as A-zitten in his cheair o' woak. In Tyndale's earliest New Testament, which

reached England in 1526, one is repeatedly spelt won. 167. But while we point

to the western counties as abounding in this feature, we must not overlook

the fact that in Yorkshire, and generally throughout the North, one is pronounced

wonn, and oats are called wu/s, as distinctly as in Gloucestershire and the

West of England. Whatever its antecedents, we must regard this w with

particular interest as being a property of the English speech. To the

Scandinavians it is ungenial; they have dropped it in words where it is of

ancient standing, and where we have it in common with the Germans, as in

week, wool, wolf, Woden, wonder, word, which the Danes call uge, uld, ulf,

Odin, under, ord. The Germans do in fact write the w in these words, SSocfye,

2BoIle, SBotf, SBunber. But they do not properly share with us our w, for

they pronounce it as our v; at least it is so pronounced in the literary

German. If, however, we listen to the voice of the people, we perceive great

variation in Germany. In the southern parts they seem to approach very nearly

to the sound of our w; and, according to Paulus Diaconus, the Lombards

exaggerated this sound, for he says that they pronounced Wodan as Gwodan.

Even in France we occasionally catch a complete w-sound, as in aiguille, out,

Edouard, Longwy. But with all this, it may still be safely said that they all

leave us in the sole possession of our w, which is accordingly a distinct

property and special birthright of the English language. 168. The influence

of association (164) explains many other peculiarities of our spelling. It

was on this principle that the word could acquired its l. This word has no

natural |

|

|

|

|

|

VARIATIONS. 163 right to the l

at all, being of the same root as can, and the second syllable in uncouth,

viz. from the verb which in Saxon was written cunnan. In would and should the

l is hereditary; but could acquired the l by mere force of association with

them. And it seems probable that the silence of the l in all three of these

words may be due to the example of could. The coud sound still kept its place

after it was written could, and at length drew would and should over to the

like pronunciation. In the poet Surrey and his contemporaries we find would

zxi<\ even could rhymed to mould', and thus we perceive that could might

easily have acquired a pronunciation answering to its new spelling. The word

fault used to be pronounced without the sound of l, but here orthography has

proved stronger than tradition. In the Deserted Village it rhymes to aught:

Yet he was kind, or if severe in aught, The love he bore to learning was in

fault. This is another instance in which we have dropped a French

pronunciation for one of our own making, and in the making of which we have

been led by the spelling. 160. 169. Between spelling and pronunciation there

is a mutual attraction, insomuch that when spelling no longer follows the

pronunciation, but is hardened into orthography, the pronunciation begins to

move towards the spelling. A familiar illustration of this may be found in

the words Derby, clerk, in which the er sounds as ar, but which many persons,

especially of that class which is beginning to claim educated rank, now

pronounce literally. The ar pronunciation was a good Parisian fashion in the

fifteenth century. Villon, the French poet of that period, affords in his

rhymes some illustrations of this. He rhymes Robert, haubert, with pluspart,

poupart; bar re with terre; appert with part. 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 6 4 II. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. But it must have been much older than the time of Villon. In

Chaucer, Prologue 391, we are not to suppose that Deriemouthe is to be

pronounced as it was by the boy who in one of our great schools was the cause

of hilarity to his class-fellows by calling that seaport Dirty-mouth. In

Chaucer's pronunciation the first syllable represents the same sound as Dart

now does. The popular sarmon, sermon, is found in Chaucer. Sarvant and

sarvice occur in Ralegh's letters. We pronounce ar in serjeant. We write ar

in farrier; and ferrier is forgotten. Both forms are preserved in the case of

person and parson: in Love's Labour's Lost, iv. 2. 78, the old editions are

divided on this word. In Ralegh we find parson in the sense of ' person.'

Merchant was originally a mere variety of spelling for marchant, but the

pronunciation has now adapted itself to the prevalent value of er. 170. There

are other familiar instances in which we may trace the influence of

orthography upon pronunciation. The generation which is now in the stage

beyond middle life, are some of them able to remember when it was the correct

thing to say Lunnon. At that time young people practised to say it, and

studied to fortify themselves against the vulgarism of saying London,

according to the literal pronunciation. At the same time Sir John was

pronounced with the accent on Sir, in such a manner that it was liable to be

mistaken for surgeon. This accentuation of ' Sir John ' may be traced further

back, however, even to Shakspeare, unless our ears deceive us, 2 Henry VI,

ii. 3. 13: |

|

|

|

|

|

VARIATIONS. 165 Compare Milton,

Sonnet xi: Thy age, like ours, O soul of Sir John Cheek, Hated not learning

worse than toad or asp, When thou taught'st Cambridge and King Edward Greek.

171. The same generation said poonish for punish (a relic of the French u in

punir); and when they spoke of a joint of mutton they called it jink or

jeynt. In some cases it approximated to the sovM&jiveynte, and this was

heard in the more retired parts among country gentlemen. This is in fact the

missing link between the ei or eye sound and the French diphthong oi or oie

in imitation of which the peculiarity originated. The French words loi and

joie are sounded as Vwa and j'wa. When the French pronunciation had

degenerated so far in such words as join, joint, that the was taken no

account of, and they were uttered as jine, jinte, a reaction set in, and

recourse was had to the native English fashion of pronouncing the diphthong

oi. Hence our present join, joint, do not always rhyme where they ought to

rhyme and once did rhyme. That beautiful verse in the 106th Psalm (New

Version) is hardly producible in refined congregrations, by reason of this

change in its closing rhyme: O may I worthy prove to see Thy saints in full

prosperity! That I the joyful choir may join, And count thy people's triumph

mine! 172. The fashion has not yet quite passed away of pronouncing Rome as

the word room is pronounced. This is an ancient pronunciation, as is well

known from puns in Shakspeare. No doubt it is the phantom of an old French

pronunciation, and it bears about the same relation to the French utterance

of Rome (pron. Ro?n) that boon does to the French don. But it is remarkable

that in Shakspeare's day the modern pronunciation (like roam) was already

heard and |

|

|

|

|

|

1 66 IT. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. recognised, and the two pronunciations have gone on side by

side till now, and it has taken so long a time to establish the mastery of

the latter. The fact probably is, that the room pronunciation has been kept

alive in the aristocratic region, which is almost above the level of

orthographic influences: while the rest of the world has been saying the name

according to the value of the letters. Room is said to have been the habitual

pronunciation of the late Lord Lansdowne and the late Lord Russell. The

Shakspearean evidence is from the following passages. King John, iii. i: Con.

O lawfull let it be That I have roome with Rome to curse a while. So also in

Julius Ccesar, i. 2. But in 1 Henry VI, iii. 1: Winch. Rome shall remedie

this. Warw. Roame thither then. The street in which Charles Dickens went to

school at Chatham bears its evidence here: Then followed the preparatory

day-school, a school for girls and boys, to which he went with his sister

Fanny, and which was in a place called Rome (pronounced Room) lane. John

Forster, Life of Charles Dickens, (1872) ch. i. 1816-21. 173. There still

exist among us a few personages who culminated under George IV, and who

adhere to the now antiquated fashion of their palmy days. With them it used

to be, and still is, a point of distinction to maintain certain traditional

pronunciations: gold as gould or gu-uld; yellow as y 'allow; lilac as leyloc;

china as cheyney, oblige as obhegt\ after the French obliger. To this group

of waning and venerable sounds, which were talismans of good breeding in

their day, may be added the pronunciation of the plural verb are like the

word air: but not without observing that, in this instance, it is the modern

pronunciation that runs counter to orthography. The following quotation from

Wordsworth, Thoughts near |

|

|

|

|

|

RECENT DIPHTHONGS. 1 67 the

Residence of Burns, exhibits it in rhyme with prayer, bear, share: But why

to him confine the prayer, When kindred thoughts and yearnings bear On the

frail heart the purest share With all that live? The best of what we do and

are, Just God, forgive! 174. Rarer are the instances in which the number of

syllables has been effected by change of pronunciation. A celebrated example

is the plural ' aches,' which appears as a disyllable in Shakspeare, Samuel

Butler, and Swift. The latter, in his own edition of ' The City Shower ' has

l old aches throb' but modern printers, who had lost the twosyllable

pronunciation, found it necessary to make good the metre thus: ' old aches

will throb.' If thou neglect'st, or dost unwillingly What I command, I'll

rack thee with old cramps; Fill all thy bones with aches; make thee roar That

beasts shall tremble at the din. Tempest, i. 2. Can by their pangs and

aches find All turns and changes of the wind. Hudibras, iii. 2. 407. Some

recent Diphthongs. 175. We will devote the remainder of this chapter to the

new English diphthongs: they are among the more conspicuous instances of that

revolution in orthography which has caused Saxon literature to look so

uncouth and strange in its own native country. To begin with the archaic EW.

Represents a terminal condensation in a small set of early English words,

viz. Andrew, Bartholomew, feverfew (French feverfuge), Grew (obsolete for

Greek), Hebrew, few (French Juif). AU. It resulted from our peculiar ae sound

of a as de |

|

|

|

|

|

1 68 II. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. scribed in the last chapter, that the English a was found

unequal to represent the French a, and accordingly we see au put for it in

many words, as chaunt, the old spelling for chant; au?it for ante; haunt from

' hanter'; laund, & frequent word in our early poetry, also written

tawnd, from the French ' lande,' and still preserved in the lawns of our

gardens. Blaunche, haunch, paunch, French ' panse '; launch, French 'lancer/

Also for Saxon a, as hlahhan laugh. And this representation of the ' a ' by

the English au, from Chaucer to Spenser, is an acknowledgment of the early

incapacity of the English a to express that full ' a ' sound. 176. OU. There

was no such diphthong as this in Saxon, though it is common in what are now

called ' Saxon ' words. It was one of the French transformations. The Saxon u

was changed to French ou, as in iung young, f>ruh trough, ful became foul,

butan keeps its u in but, and changes it in about. Thus the Saxon nehgebur

became neighbour in conformity to such terminations as honour, favour, which

represented a French -eur. This ou is sometimes present in sound when absent

from the spelling. If we compare the words move, prove, with such words as

love, dove, shove, we become aware that the former, though they have laid

aside their French spelling from mouvoir, prouver, yet have retained their

French sound notwithstanding. 177. 01. This is no Saxon diphthong, but Saxon

words readily admitted it. It came from the French oui or eui, or even ou.

The Saxon sol borrowed from the French souil a new vocalisation, and hence

the English soil. The French feuil a leaf, has given us foil in several

technical uses; and from fouler, to tread down, we have the verb to foil. The

Saxon tilian lives on in the verb to till the ground; while its French

vocalisation has resulted in toil. |

|

|

|

|

|

RECENT DIPHTHONGS. 169 OE. If

this combination occurred only in such instances as foe, hoe, roe, toe, woe,

it would not call for notice here, because there is no diphthong; the e in

these cases being but the ^-subscript, though no consonant intervenes. But

there was an oe of a thoroughly diphthongal character, which represented the

French eu or sometimes ou. The French peuple became poeple in Chaucer, with

variants puple and peple. So we find moeuyng moving, proeued proved, and

woemen women. The sound of this oe is preserved in canoe, shoe. EO. This has

no connection with the Saxon eo. Ben Jonson said, ' it is found but in three

words in our tongue, yeoman, people, jeopardy, which were truer written

ye'man, pe'ple, jepardy! In two out of these three cases it is the

transposition of oe representing French eu, as treated above. 178. EE. This

is not properly a diphthong, but a long vowel; it is the long ' i \ But it is

convenient to speak of it here, with a view to introduce the present tendency

of diphthongs to merge into this sound \ English spelling has been produced

by such a variety of heterogeneous causes that its inconsistencies are not to

be wondered at. Grimm has remarked on the want of regularity in our vowel

usage: for we use a double e in thee, and a single one in vie, whereas the

vowel-sound is alike in the pronunciation. The probable cause was the need of

distinction between the pronoun thee and the definite article the words

which down to the end of the fifteenth century are spelt alike, and often

check the reader. The eye has its claims as well as the ear, when so much is

written and read; and this accounts for many cases of dissimilar spelling of

similar sounds, as be the verb and bee the insect. 1 Below, 191, in a short

program of phonetic amendments, this ee gains seven places and loses none. |

|

|

|

|

|

I70 77. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. 179. EA. This combination is particularly interesting, and we

select it for expansion. It has no connection with the Saxon diphthong of the

same form. It is not found in Chaucer. Where we write ea he wrote e: beste

beast, bred bread, clene clean, ded dead, del deal, deth death, dere dear,

grete great, herte heart, mel meal, pes peace, pies please, redy ready,

sprede spread, tere tear, whete wheat. The change from e to ea may be thus

accounted for. Chaucer's e was the French e-ouvert, which sounded as eh, not

far from the vocalism of day, hay, nay. But in the English mouth this e

became less open and more shrill continually, till at last it merged in ' i '

which is its present lot. The a was then added to it in such syllables as

adhered to the former sound; and thus I suppose ea was at first a

reinforcement of e-ouvert, just as gh was a reinforcement of the old

gutturality of h. (132.) At first ea sounded as ay; but after a while it

found the old tendency too strong for it, and it drifted away in that very

direction from which the addition of a had vainly sought to stay it. And now

most of the ea syllables are pronounced as ee. Our illustration of this shall

be connected with the history of the word tea. 180. We have all heard some

village dame talk of her dish o' toy; but the men of our generation are

surprised when they first learn that this pronunciation is classical English,

and is enshrined in the verses of Alexander Pope. The following rhymes are

from the Rape of the Lock. Soft yielding minds to Water glide away, And sip,

with Nymphs, their elemental Tea. Canto i. Here thou, great Anna! whom three

realms obey, Dost sometimes counsel take and sometimes Tea. Canto iii. That

this was the general pronunciation of good company down to the close of the

last century there is no doubt. The following quotation will carry us to

1775, the date |

|

|

|

|

|

EA COME TO SOUND AS EE. 171 of a

poem entitled Bath and It's Environs, in three cantos, p. 25: Muse o'er some

book, or trifle o'er the tea, Or with soft musick charm dull care away. This

old pronunciation was borrowed with the word from the French, who still call

the Chinese beverage toy, and write it the. And when tea was introduced into

England by the name of toy, it seemed natural to represent that sound by the

letters tea. 181. Although there are a great many words in English which hold

the diphthong ea, as beat, dear, death, eat, fear, gear, head, learn, meati,

neat, pear, read, seat, teat, wean, yet the cases of ea ending an English

word are very few. Ben Jonson, in his day, having produced four of them, viz.

flea, plea, sea, yea, added, 'and you have at one view all our words of this

termination/ He forgot the word lea, or perhaps regarded it as a bad spelling

for ley or lay. This makes five. A sixth, pea, has come into existence since.

To these there has been added a seventh, viz. tea. At the time when the

orthography of tea was determined, it is certain that most instances of ea

final sounded as ay, and probable that all did. In a number of words with ea

internal, the pronunciation differed. But even in these cases there is room

to suspect that the ay sound was once general, if not universal. We still

give it the ay sound in break, great, measure, pleasure, treasure. In Surrey

we find heat rhyme to great, and no doubt it was a true rhyme. Surrey

pronounced heat as the majority of our countrymen, at least in the west

country, still do, viz. as hayt. The same poet rhymes ease to assays: The

peasant, and the post, that serves at all assays; The ship-boy, and the

galley-slave, have time to take their ease; where it is plain that ease

still kept to the French sound of |

|

|

|

|

|

172 //. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. ai'se. Then, further, the same poet has in a sonnet the

following run of rhyming words: |

|

|

|

|

|

EA COME TO SOUXD AS EE. 1 73

French fait, suggests the sounds fayi and ayt. The same applies Cofeature O.

French faiture, eagle French aigle, eager French aigre. In The Stage-Players

Complaint (1641), we find nay spelt nea: ' Nea you know this well enough, but

onely you love to be inquisitive.' 183. Michael Drayton, Polyolbion, xixth

song (1662) rhymed seas with raise; Cowper rhymed sea with survey; and Dr.

Watts (1709) rhymed sea to away. But timorous mortals start and shrink To

cross this narrow sea, And linger shivering on the brink, And fear to launch

away. Book of Praise, clxi. Goldsmith puts this into the mouth of an

under-bred fine-spoken fellow: An under-bred fine-spoken fellow was he, And

he smil'd as he look'd on the venison and me. ' What have we got here? Why,

this is good eating! Your own, I suppose or is it in waiting?' The Haunch

of Venison, When, in 1765, Josiah Wedgwood, having received his first order

from Queen Charlotte, wrote to get some help from a relative in London, he

described the list of tea-things which were ordered, and he spelt the word

tray thus, ' trea ' for so only can we understand it ' Tea-pot &

stand, spoon-trea.' The orthography may be either his own or that of Miss

Chetwynd, from whom the instructions came. Family names offer some examples

to the same effect. A friend informs me that he had once a relative, who in

writing was Mr. Lea, but he pronounced his name ' Lay '; and I am courteously

permitted to use for illustration the name of Mr. Rea, of Newcastle, the

well-known organist, whose family tradition renders the name as ' Ray.' The |

|

|

|

|

|

174 u - SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. little river in Shropshire, which is written ^Rea, is called

Ray. 184. If it has been made plain that ea sounded ay, it will be a step to

the clearing of an old anomaly. It has been asked why we spell conceive with

ei, and yet spell believe, reprieve with ie. The difficulty lies in the fact,

that the pronunciation of these dissimilar diphthongs is now the same. And

the answer lies in this that the pronunciation was formerly different.

Those words which we now write with ei to wit, deceive, perceive, conceive,

receive were all pronounced with a -cayve sound, as they still are in many

localities. The readiest proof of this is in the facts, (i) that you will not

find them rhymed with words of the ie type, and (2) that you will continually

find them spelt with ea, as deceave,perceave, conceave, receave. (3) But

however these words are spelt in' the early prints, they are constantly

distinguished in some way or other, as decerned, beleeued. Above, 145.

Another illustration of the old power of ea may be gathered from a source

which has not received due attention: I mean the pronunciation of English in

Ireland. It is well known that there resayve is the sound for receive, pays

for pease, say for sea, aisy for easy, baste for beast. These, and many other

so-called Irishisms, are faithful monuments of the pronunciation of our

fathers, at the time when English was planted in Ireland. All these words

have now gone into the ^-sound which is represented by ie in believe, and

there is no doubt that this sound is a very encroaching one. There have long

been two pronunciations of great, namely greet and grayt; though the latter

is still dominant, and is likely to remain so. It is in bookish words that

the progress of the ^-sound will be most rapid, because the teacher will

there be less obstructed by usage, and teachers love general rules. Therefore

ea once |

|

|

|

|

|

EA COME TO SOUND AS EE. 1 75 ee

shall be always ee. A child learning to read, and coming to the word inveigle

shall be told to call it inveegle, though the best usage at present is to say

invaygle. Sir Thomas Browne spelt it with ea: These Opinions I never

maintained with pertinacy, or endeavoured to enveagle any mans belief unto

mine. Religio Medici, fol. 1686; p. 4. Among the words which still vacillate

between the two sounds of ea, is the word break: Still feel the breeze down

Ettrick break Although it chill my withered cheek. Scott. Ah, his eyelids

slowly break Their hot seals, and let him wake! Matthew Arnold. That the

latter is the pronunciation at the present time there can be no doubt: and

yet the former is heard from persons of weight enough to suggest the doubt

whether it may not perhaps establish itself in the end. Thus we see that ea

has in numerous instances changed its sound from that of ay to that of ee.

How are we to render any account of so apparently capricious a movement,

except by saying that a sentiment has taken possession of the public mind to

the effect that ay is a rude braying sound, while ee is a refined and sweetly

bleating one. Or, shall we suppose that this is only a reprisal and natural

compensation for the area lost by this ee sound when it was ejected from its

ancient lot, and the ' i ' was invaded by the sound of Igh? Leaving such

enquiries to the younger student, I will add two striking examples of the

encroachment of this popular favourite, this ee sound. The first is the

well-known instance of Beauchamp, which is pronounced Beecham. The second is

more remarkable. All along I have assumed that the written ay is constant in

value, and capable of being referred to as a standard, as the unshaken

representative of that sound which ea had and |

|

|

|

|

|

1 7 6 II. SPELLING AND

PRONUNCIATION. has lost. But there is at least one remarkable exception to

this assumed security of ay. For the last forty years or so there has been a

prevailing tendency to pronounce quay kee; and Torquay is most numerously

called Torquee. How has this habit grown? It seems to prove that our

pronunciation is not set by the best examples; for nearly all those whom I

should have thought most worthy of being imitated have from the earliest time

in my memory said kay and Tor-kay. 185. In summing up the case of Spelling

and Pronunciation, we may make good use of the example of tea. When this word

was first spelt, the letters came at the call of the sound: the spelling

followed the pronunciation. Since that time, the letters having changed their

value, the sound of the word has shared the vicissitude of its letters; the .

pronunciation has followed the spelling. It is manifest that these movements

have one and the same aim, namely, to make the spelling phonetically

symbolize the pronunciation. There are two great obstacles to such a

consummation: (i) The letters of the alphabet are too few to represent all

the variety of simple sounds in the English language; and (2) even what they

might do is not done, because of the restraining hand of traditional

association. The consequence is, that when we use the word ' orthography,' we

do not mean a mode of spelling which is true to the pronunciation, but one

which is conventionally correct. The spirit of Orthography is embodied in

this dictum of Samuel Johnson: ' It is more important that the law should be

known than that it should be right.' The notion of Right in orthography has

been more obscured in the English than in any other language. For there have

swept over it two great and lengthened waves of foreign influence, which have

divided the last eight |

|

|

|

|

|

CROSS CURRENTS. J J J hundred

years between them; namely, First the revolution from Saxon to French

orthography; and Secondly, that from the French to the Latin complexion.

Still, the desire for a true, natural, phonetic, system of spelling is not

extinguished, and it has from time to time pushed itself into notice. |

|

|

|

|

|

APPENDIX TO CHAPTER II. On

Spelling-reform. 186. Alphabetic writing is essentially phonetic. It was the

result of a sifting process which was conducted with little conscious design,

by which all the other suggestions of picturewriting were gradually

eliminated, and each figure was brought to represent one of the simple sounds

obtained by the analysis of articulate speech. The historical development of

Letters tells us what their essence and function is viz. The expression of

the Sound of words. Spelling is the counterpart of pronunciation. But there

is a law at work to dissever this natural affinity. Pronunciation is ever

insensibly on the move, while spelling grows more and more stationary. The

agitation for spelling-reform which appears in cultivated nations from time

to time, aims at restoring the harmony between these two. Among the Romans

a people eminently endowed withthe philological sense there were some

attempts of this kind, one of which is of historical notoriety. The emperor

Claudius was a phonetic reformer, and he wrote a book on the subject while in

the obscurity of his early life. Three letters as a first instalment of

reform he forced into use when he was emperor, but they were neglected after

his time and forgotten. Yet two of the three have been quietly resumed by a

late posterity. These represented I and U consonants as distinct from the

connate vowels. In the seventeenth century the European press gave these

powers to the forms J and V. Claudius was not however the first to direct

attention to the inadequacy of the Roman alphabet. Verrius Flaccus had made a

memorable proposal with regard to the letter M. At the end of Latin words it was

indistinctly heard, and therefore he proposed to cut the letter in two, and

write only half of it in such positions thus, N. 187. During the last three

centuries many proposals for spelling-reform have been made in this country

and in America. Among the reformers we find distinguished names 1 . 1 Sir

John Cheke, 1540 (Strype's Life). John Hart, 1569: 'An Orthographic

conteyning the due order and reason howe to write or painte thimage |

|

|

|

|

|

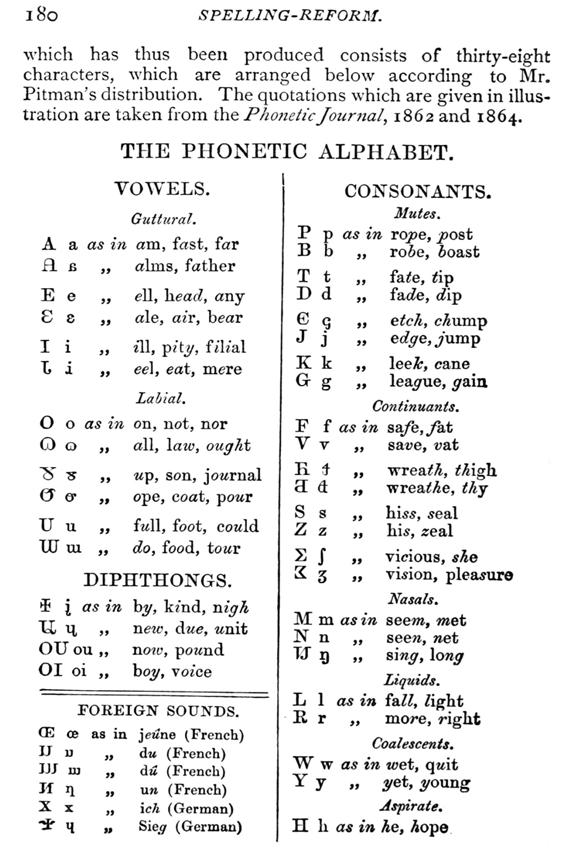

PHONETIC SPELLING. ] 79 But for

practical results, the first was Noah Webster. In his Dictionary, 1828, he

spelt traveler, worshiped, favor, honor, center, and these were widely

adopted in American literature, especially the ejection of the French u from

the termination -our. But he was an etymological as well as a phonetic

reformer. And when he proceeded to write bridegoom, /ether, for bridegroom,

feather, his public declined to follow him, and he retraced his steps. Julius

Hare and Connop Thirlwall in their joint translation of Niehbuhr's History

made some reforms, partly phonetic, partly etymological; such as forein,

sovran, stretcht. Thirlwall returned to the customary spelling in his History

of Greece 1835; but he covered his retreat with an overloaded invective at

English prejudice, which has since been quoted oftener than his wisest

sentences. A strictly phonetic spelling-reform requires that we should have a

separate character for every separate sound, and that no character should

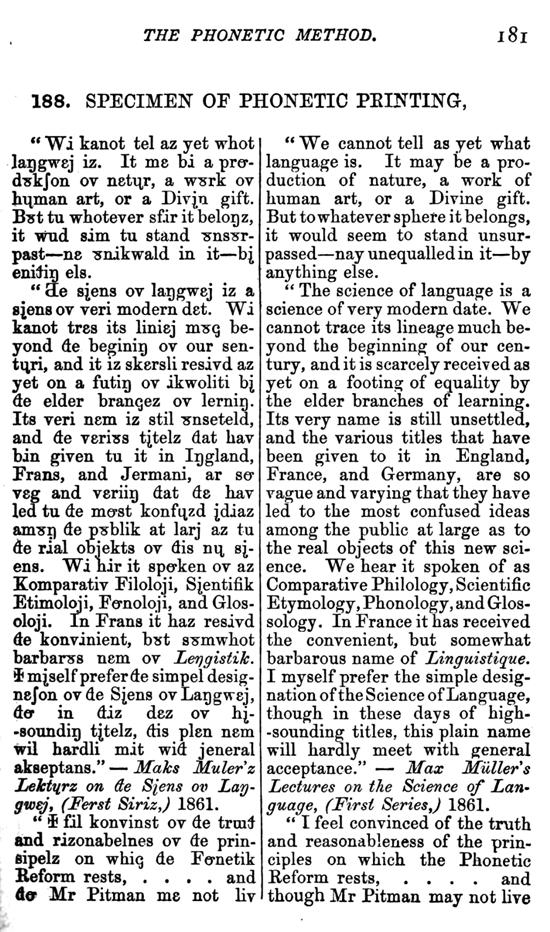

ever stand for any but its own particular sound. One such system has acquired

the consistency which a working experience alone can give. Mr. Pitman's

phonetic alphabet has been tested by thirty years of practical work, in

printing books large and small, as well as in the continuous appearance of

the Phonetic Journal, which is now in its thirty-sixth year. In this system

the Roman alphabet is adopted as far as it goes, and new forms are added for

the digraphs which, like th, sh, represent simple sounds. The place of

publication is Bath, but the movement first took a practical shape in

Birmingham, where in 1843 Mr. Thomas Wright Hill originated a Phonetic Fund

to meet the necessary sacrifices of such an experiment. Mr. Hill was the

father of Matthew Davenport Hill, Q.C., and of Sir Rowland Hill, and of three

other distinguished sons. After the meeting of 1843, ^ r - Ellis helped Mr.

Pitman in the formation of the new characters, and from that year to the

present the system has been in operation. The alphabet of marine's voice,

moste like to the life or nature.' Bishop Wilkins, 1668. Benjamin Franklin,

1768. William Pelham, Boston, U.S. 1808, printed ' Rasselas' phonetically.

Abner Kneeland, Philadelphia, 1825. Rev. W. Beardsley, St. Louis, 1841.

Andrew Comstock, Philadelphia, 1846. John S. Pulsifer, Orswigsburg,

Pennsylvania, 1 848. Alexander Melville Bell, London, 1865. N 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

i8o |

|

|

|

|

|

181THE PHONETIC METHOD. |

|

|

|

|

|

182 |

|

|

|

|

|

183 |

|

|

|

|

|

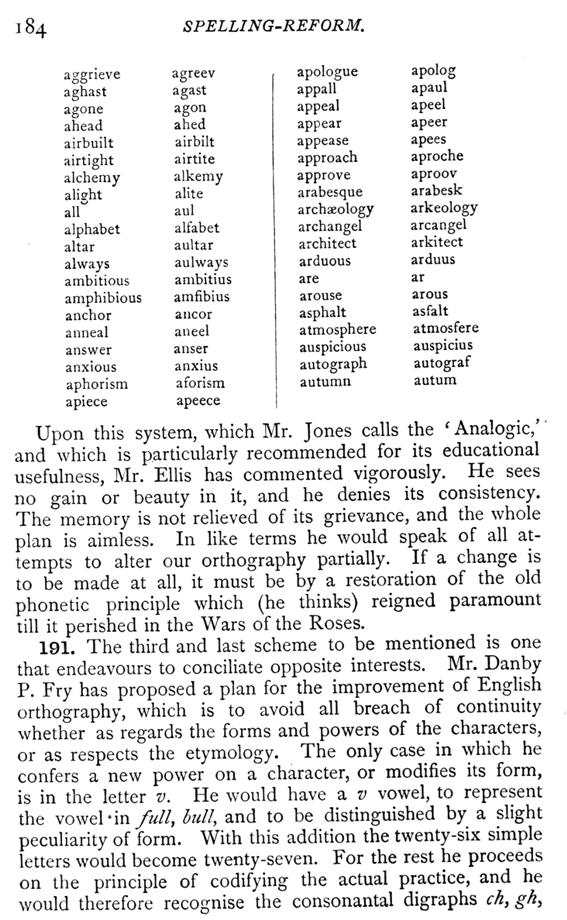

1 84 |

|

|

|

|

|

CONSISTENT METHODS. 1 85 kh,

ph, rh, sh, th, wh, ng, as alphabetic characters, adding to them dh and zh.

He would write the and that as ' dhe ' and ' dhat ': and azure he would write

' azhure/ After the same manner the vocalic digraphs ee, ai, aa, au, oa, 00,

oz, ou, would be counted as primary letters, and thus complete an alphabet of

forty-six characters. The e final would be discarded in all instances in

which it is really idle, having no effect ori the preceding vowel; and freez,

gauz, would take the place of freeze, gauze (158). In this scheme the idea

seems to be that an orthography reasonably phonetic and consistent ought

to be -discovered without the sacrifice of tradition and historical

association. It would be ' not uniform spelling, but consistent spelling;

so dhat dhat half ov dhe language which iz spelt etymologically may be spelt

consistently on dhe etymological principle, while dhe odher half ov dhe

language which iz spelt phonetically may be spelt consistently on dhe

phonetic principle.' The phonetic principle is to be admitted when it does

not conflict with the etymological. For instance, the s would be rejected

from island (properly Hand), but retained in isle, to which it rightly

belongs. For Mr. Fry proposes, as a means of reconciling tradition with

current pronunciation, that silent letters should be preserved whenever

required by etymology, but otherwise omitted. 192. More plans are proposed

than we have enumerated or have space to enumerate. It is plain where so many

schemes are broached that the need of some change is very widely felt, but

there seems to be little agreement as to the direction reform should take. If

however a distinct path is chosen, it will at once lay open to our view a new

and as yet unnoticed difficulty. When we enter on the path of

spelling-reform, we pass from that on which we are tolerably agreed, namely

conventional orthography, to raise a new structure on a foundation of

unascertained stability. The moment you resolve to spell the sound, you bring

into the foreground what before lay almost unobserved the great diversity

of opinion which exists as to the correct sound of many words. |

|

|

|

|

|

CHAPTER III. OF INTERJECTIONS.

193. The term Interjection signifies something that is ' pitched in among '

things of which it does not naturally form a constituent part. The

Interjection has been so named by grammarians in order to express its

relation to grammatical structures. It is found in them, but it forms no part

of them. The interjection may be defined as a form of speech which is

articulate and symbolic but not grammatical. It is only to be called

grammatical in that widest sense of the w r ord, in which all that is

written, including accents, stops, and quotation marks, would be comprised

within the notion of grammar. When we speak of grammar as the handmaid of

logic, then the interjection must stand aside. Emotion is quick, and leaves

no time for logical thought: if it use grammatical phrases they must be ready

made and familiar to the lips; there is not time to select what is

appropriate or consecutive. Hence the limited variety of interjections, and

the almost unlimited use of single forms. An interjection implies a meaning

which it would require a whole grammatical sentence to expound, and it may be

regarded as the rudiment of such a sentence. But it is a confusion of thought

to rank it among the parts of speech. It is not in any sense a part; it is a

whole (though an indistinct) expression of feeling or of thought. An inter |

|

|

|

|

|

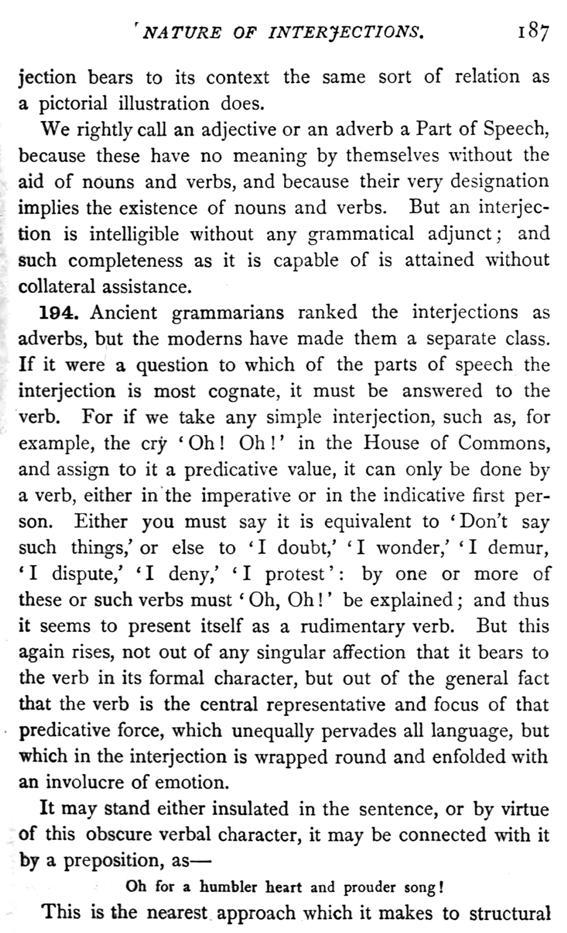

'nature of interjections. 187

jection bears to its context the same sort of relation as a pictorial

illustration does. We rightly call an adjective or an adverb a Part of

Speech, because these have no meaning by themselves without the aid of nouns

and verbs, and because their very designation implies the existence of nouns

and verbs. But an interjection is intelligible without any grammatical

adjunct; and such completeness as it is capable of is attained without

collateral assistance. 194. Ancient grammarians ranked the interjections as

adverbs, but the moderns have made them a separate class. If it were a

question to which of the parts of speech the interjection is most cognate, it

must be answered to the verb. For if we take any simple interjection, such

as, for example, the cry ' Oh! Oh! ' in the House of Commons, and assign to

it a predicative value, it can only be done by a verb, either in the

imperative or in the indicative first person. Either you must say it is

equivalent to 'Don't say such things/ or else to ' I doubt,' ' I wonder/ ' I

demur, 1 1 dispute/ ' I deny/ ' I protest ': by one or more of these or such

verbs must ' Oh, Oh! ' be explained; and thus it seems to present itself as a

rudimentary verb. But this again rises, not out of any singular affection

that it bears to the verb in its formal character, but out of the general

fact that the verb is the central representative and focus of that

predicative force, which unequally pervades all language, but which in the

interjection is wrapped round and enfolded with an involucre of emotion. It

may stand either insulated in the sentence, or by virtue of this obscure

verbal character, it may be connected with it by a preposition, as Oh for a

humbler heart and prouder song! This is the nearest approach which it makes

to structural |

|

|

|

|

|

1 88 III. OF INTERJECTIONS.

relations with the sentence, and this sort of relation it can have with a

noun or pronoun, as They gaped upon me with their mouths, and said: Fie on

thee, fie on thee, we saw it with our eyes. Psalm xxxv. 21. From that same

germ of verbal activity it joins readily with the conjunction. Operating with

the conjunction, it rounds off and renders natural an abrupt beginning, and

forms as it were the bridge between the spoken and the unspoken: Oh if in

after life we could but gather The very refuse of our youthful hours!

Charles Lloyd. Because of the variety of possible meanings in the

interjection, writing is less able to represent interjections than to express

grammatical language. Even in the latter, writing is but an imperfect medium,

because it fails to convey the accompaniments, such as the look, the tone,

the gesture. This defect is more evident in the case of interjections, where

the written word is but a very small part of the expression; and the manner,

the pitch of tone, the gesture, is nearly everything. 195. Hence also it

comes to pass that the interjection is of all that is printed the most

difficult thing to read well aloud; for not only does it require a rare

command of modulation, but the reader has moreover to be perfectly acquainted

with the situation and temperament of the person using the interjection.

Shakspeare's interjections cannot be rendered with any truth, except by one

who has mastered the whole play. In the accompaniments of tone, air, action,

lies the rhetoric of the interjection, which is used with astonishing effect

by children and savages. For it is to these that the interjection more

especially belongs; and in proportion to the march of culture is the decline

of interjectional speech. |

|

|

|

|

|

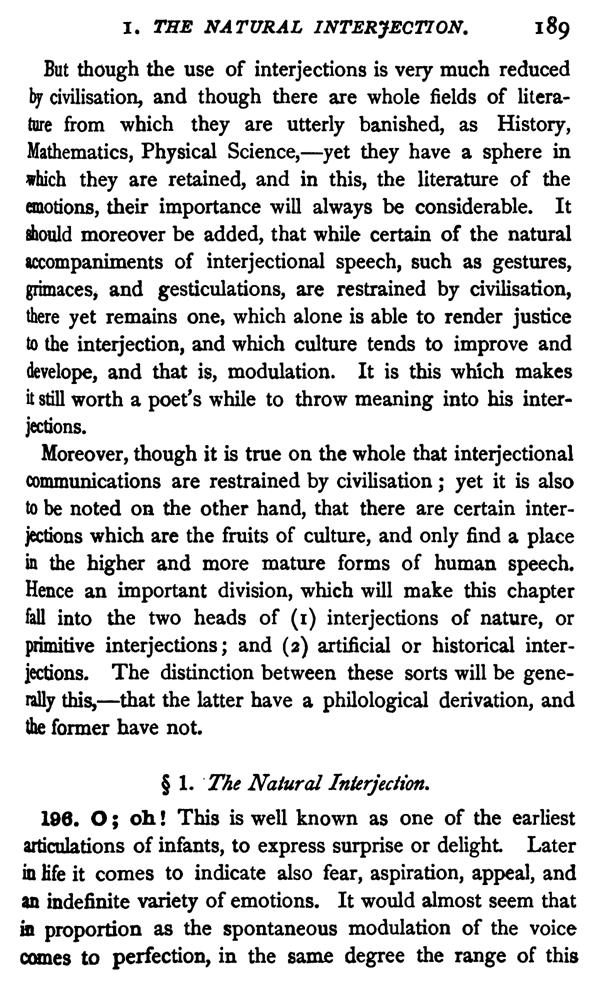

I. THE NATURAL INTERJECTION. 1

89 But though the use of interjections is very much reduced by civilisation,

and though there are whole fields of literature from which they are utterly

banished, as History, Mathematics, Physical Science, yet they have a sphere

in which they are retained, and in this, the literature of the emotions,

their importance will always be considerable. It should moreover be added,

that while certain of the natural accompaniments of interjectional speech,

such as gestures, grimaces, and gesticulations, are restrained by

civilisation,, there yet remains one, which alone is able to render justice

to the interjection, and which culture tends to improve and develope, and

that is, modulation. It is this which make^ it still worth a poet's while to

throw meaning into his interjections. Moreover, though it is true on the

whole that interjectional communications are restrained by civilisation; yet

it is also to be noted on the other hand, that there are certain

interjections which are the fruits of culture, and only find a place in the

higher and more mature forms of human speech. Hence an important division,

which will make this chapter fall into the two heads of (1) interjections of

nature, or primitive interjections; and (2) artificial or historical

interjections. The distinction between these sorts will be generally this,

that the latter have a philological derivation, and the former have not. § 1

. The Natural Interjection. 196. O; oh! This is well known as one of the

earliest articulations of infants, to express surprise or delight. Later in

life it comes to indicate also fear, aspiration, appeal, and an indefinite

variety of emotions. It would almost seem that in proportion as the

spontaneous modulation of the voice . comes to perfection, in the same degree

the range of this |

|

|

|

|

|

190 ///. OF INTERJECTIONS. most

generic of all interjections becomes enlarged, and that according to the tone

in which oh is uttered, it may be understood to mean almost any one of the

emotions of which humanity is capable. This interjection owes its great

predominance to the influence of the Latin language, in which it was very

frequently used. And there is one particular use of it which more especially

bears a Latin stamp. That is the of thevocative case, as when in prayers we

say, Lord; Thou to whom all creatures bow. We should distinguish between the

sign of the vocative and the emotional interjection, writing O for the

former, and oh for the latter, as Who could have thought such darkness lay

concealed Within thy beams, O Sun! Blanco White. But she is in her grave,

and oh The difference to me! Wordsworth. This distinction of spelling

should by all means be kept up, as it is well founded. There is a difference between

' O sir! ' ' O king! ' and ' Oh! sir,' ' Oh! Lord/ both in sense and

pronunciation. As to the sense, the prefixed merely imparts to the title a

vocative effect; while the Oh conveys some particular sentiment, as of

appeal, entreaty, expostulation, or some other. And as to sound, the O is

enclitic; that is to say, it has no accent of its own, but is pronounced with

the word to which it is attached, as if it were its unaccented first

syllable. The term Enclitic signifies ' reclining on/ and so the interjection

in ' O Lord ' reclines on the support afforded to it by the accentual

elevation of the word ' Lord.' So that ' O Lord' moves like such a disyllable

as alight, alike, away) in which words the metrical stroke could never fall

on the first syllable. Oh I on the contrary, is one of the fullest of |

|

|

|

|

|

I. THE NATURAL INTERJECTION. 191

monosyllables, and it would be hard to place it in a verse except with the

stress upon it. The example from Wordsworth illustrates this. Precedence has

been given to this interjection because it is the commonest of the simple or

natural interjections, not that it is one of the longest standing in the

language. Our oldest interjections are la and wa, and each of these merits a

separate notice. 197. La is that interjection which in modern English is

spelt lo. It was used in Saxon times, both as an emotional cry, and also as a

sign of the respectful vocative. The most reverential style in addressing a

superior was La leof, an expression not easy to render in modern English, but

which is something like my liege, or my lord, or sir. In modern times it has

taken the form of lo in literature, and it has been supposed to have

something to do with the verb to look. In this sense it has been used in the

New Testament to render the Greek l8oi> that is, Behold! But the

interjection la was quite independent of another Saxon exclamation, viz. loc,

which may with more probability be associated with locian, to look. The fact

seems to be that the modern lo represents both the Saxon interjections la and

loc, and that this is one among many instances where two Saxon words have

been merged into a single English one. Lo, how they feignen chalk for cheese.

Gower, Confessio Amantis, vol. i. p. 17, ed. Pauli. 198. The la of Saxon

times has none of the indicatory or pointing force which lo now has, and

which fits it to go so naturally with an adverb of locality, as ' Lo here,'

or ' Lo there'; or Lo! where the stripling, wrapt in wonder, roves. Beattie,

Minstrel, Bk. i. |

|

|

|

|

|

J 92 III. OF INTERJECTIONS.

While lo became the literary form of the word, la has still continued to

exist more obscurely, at least down to a recent date, even if it be not still

in use. La may be regarded as a sort of feminine to lo. In novels of the

close of last century and the beginning of this, we see la occurring for the

most part as a trivial exclamation by the female characters. In Miss

Edgeworth's tale of The Good French Governess, a silly affected

boarding-school miss says la repeatedly: 4 La! ' said Miss Fanshaw, ' we

had no such book as this at Suxberry House.' Miss Fanshaw, to shew how well

she could walk, crossed the room, and took up one of the books. 4 Alison upon

Taste that 's a pretty book, I daresay; but la! what 's this, Miss

Isabella? A Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments dear me! that must be a

curious performance by a smith! a common smith!' In The Election: a Comedy,

by Joanna Baillie (1798), Act ii. Sc. 1, Charlotte thus soliloquises:

Charlotte. La, how I should like to be a queen, and stand in my robes, and

have all the people introduced to me! And when Charles compares her cheeks to

the 'pretty delicate damask rose/ she exclaims, ' La, now you are flattering

me.' 199. That this trivial little interjection descends from early times,

and that it is in all probability one with the old Saxon la, we may cite the

authority of Shakspeare in the mid interval, who, in The Merry Wives of

Windsor, puts this exclamation into the mouths of Master Slender first, and

of Mistress Quickly afterwards. Slen. Mistris Anne: your selfe shall goe

first. Anne. Not I sir, pray you keepe on. Slen. Truely, I will not goe

first: truely la; I will not doe you that wrong. Anne. I pray you Sir. Slen.

He rather be vnmannerly, then troublesome; you doe your selfe wrong

indeede-la. (Act i. Sc. I.) |

|

|

|

|

|

PRIMARY INTERJECTIONS. 193 Here

the interjection seems to retain somewhat of its old ceremonial significance:

but when, in the ensuing scene, Mistress Quickly says, ' This is all

indeede-la: but ile nere put my finger in the fire, and neede not/ there is

nothing in it but the merest expletive. 200. Wa has a history much like that

of la. It has changed its form in modern English to wo. ' Wo,' in the New

Testament, as Rev. viii. 13, stands for the Greek interjection oval and the

Latin vae. In the same way it is used in many passages in which the

interjectional character is distinct. This word must be distinguished from

woe, which is a substantive. For instance, in the phrase 'weal and woe.' And

in such scriptures as Prov. xxiii. 29: 'Who hath woe? who hath sorrow?' The

fact is, that there were two distinct old words, namely, the interjection wa

and the substantive woh, genitive woges, which meant depravity, wickedness,

misery. Often as these have been blended, it would be convenient to observe

the distinction, which is still practically valid, by a several orthography,

writing the interjection wo, and the substantive woe. This interjection was

compounded with the previous one into the forms wala and walawa a frequent

exclamation in Chaucer, and one which, before it disappeared, was modified

into the feebler form of wellaway. A still more degenerate variety of this

form was well-a-day. Pathetic cries have a certain disposition to implicate

the present time, as in woe worth the day! The Norman cry Harow coupled with

the Saxon walawa is often met with in our early literature, as 'Harrow and

well away!' Faery Queene, ii. 8. 46. 201. There was yet another compound

interjection made with la by prefixing the interjection ea. This was the

Saxon eala; ' Eala J>u wif mycel ys )?in geleafa,' Oh woman, |

|

|

|

|

|

194 In - 0F INTERJECTIONS. great

is thy faith, Matthew xv. 28; ' Eala faeder Abraham, gemiltsa me/ Oh father

Abraham, pity me, Luke xvi. 24. This eala may have made it easier to adopt

the French he'las, in the form alas, which appears in English of the

thirteenth century, as in Robert of Gloucester, 4198, 'Alas! alas! f>ou

wrecche mon, wuch mysaventure haf> f>e ybrogt in to J>ys stede/

Alas! alas! thou wretched man, what misadventure hath brought thee into this

place? And in Chaucer it is a frequent interjection. Alias the wo, alias the

peynes stronge, That I for yow haue suffred, and so longe; Alias the deeth,

alias myn Emelye, Alias departynge of our compaignye, Alias myn hertes

queene, alias my wyf, Myn hertes lady, endere of my lyf. Knight's Tale. Alack

seems to be the more genuine representation of eala, which, escaping the

influence of he'las, drew after it (or preserved rather?) the final guttural

so congenial to the interjection. Thus the modern alack suggests an old form

ealah. This interjection has rather a trivial use in the south of England,

and we do not find it used with a dignity equal to that of alas, until by Sir

Walter Scott the language of Scotland was brought into one literature with our

own. Jeanie Deans cries out before the tribunal at the most painful crisis of

the trial: ' Alack a-day! she never told me/ Still, the word is on the whole

associated mainly with trivial occasions, and in this connection of ideas it

has engendered the adjective lackadaysical, to characterise a person who

flies into ecstasies too readily. 202. Pooh seems connected with the French

exclamation of physical disgust: Pouah, quelle infection I But our pooh

expresses an analogous moral sentiment: ' Pooh I pooh! it 's all stuff and

nonsense.' |

|

|

|

|

|

PRIMARY INTERJECTIONS. 1 95

Psha, Pshaw, expresses contempt. 'Doubt is always crying psha and sneering.'

Thackeray, Humourists, p. 69. Tush. Now little used, but frequent in

writers of the sixteenth century, and familiar to us through the Psalter of

1539. Heigh ho. Some interjections have so vague, so filmy a meaning, that it

would take a great many words to interpret what their meaning is. They seem as

well fitted to be the echo of one thought or feeling as another; or even to

be no more than a mere melodious continuance of the rhythm: How pleasant it

is to have money, heigh ho! How pleasant it is to have money. Arthur H.

Clough. This will suffice to exhibit the nature of the first class of

interjections; those which stand nearest to nature and farthest from art \

those which owe least to conventionality and most to genuine emotion; those

which are least capable of orthographic expression and most dependent upon

oral modulation. It is to this class of interjections that the following

quotation applies. It has long and reasonably been considered that the place

in history of these expressions is a very primitive one. Thus De Brosses

describes them as necessary and natural words, common to all mankind, and

produced by the combination of man's conformation with the interior

affections of his mind. Edward B. Tylor, Primitive Culture, ch. v. vol. i.

p. 166. And this writer has produced a large collection of evidence tending

to the probability that the affirmative answers aye, I (102, 205), yea, yes,

are of this primitive class of words, although their forms may have been

modified by admixture of grammatical material. |

|

|

|

|

|

ig6 III. OF INTERJECTIONS. |

|

|

|

|

|

SECONDARY INTERJECTIONS. 1 97

when the authority of the Speaker was withdrawn, it was hardly possible to

preserve order. Sharp personalities were exchanged. The phrase ' hear him,' a

phrase which had originally been used only to silence irregular noises, and