kimkat2123k The Philology

of the English Tongue. John Earle, M.A. Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the

University of Oxford. Third Edition. 1879.

14-11-2018

● kimkat0001 Yr Hafan www.kimkat.org

● ● kimkat2001k

Y Fynedfa Gymraeg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwefan/gwefan_arweinlen_2001k.htm

● ● ● kimkat0960k Mynegai ir holl destunau yn y wefan hon www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_llyfrgell/testunau_i_gyd_cyfeirddalen_4001k.htm

● ● ● ● kimkat0960k

Mynegai ir testunau Cymraeg yn y wefan hon www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/sion_prys_mynegai_0960k.htm

● ● ● ● ● kimkat2121k The Philology of the English Tongue /

Astudiaeith Gymharol or Iaith Saesneg 1879 - Y Gyfeirddalen

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/testun-246_philology-english-tongue_earle_1879_y-gyfeirddalen_2121k.htm

● ● ● ● ● ● kimkat2123k

y tudalen hwn

|

|

|

Gwefan

Cymru-Catalonia |

|

.

...

llythrennau duon = testun wedi ei gywiro

llythrennau gwyrddion =

testun heb ei gywiro

.....

|

|

|

|

|

300

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. widely prevalent diminutival, of which we have but a few

and those rather obscure examples as, bodkin, catkin, grimalkin, ladkin,

lakin = ladykin Sh, lai?ibki?i, napkin, kilderkin, pipkin. 377. 318. In -ing;

as king cyning, lording, shilling, sweeting Sh, and the Saxon execrative

nithing. This termination nowhere shews the simplicity of its original use

better than in apple-naming, as, codling, pippin (i. e. pipping), sweeting,

wilding. In German the formative -ling is numerous in the naming of apples

and of esculent fungi: Grimm 3. 376 and 782. A childe will chose a sweeting,

because it is presentlie faire and pleasant. R. Ascham, Scholemaster i. Ten

ruddy wildings in the wood I found. John Dryden, Virgil, Eel. iii. 107. This

-ing became the formative of the Saxon patronymic,as JElfred -ZEfelwulfing,

Alfred the son of ^Ethelwulf; JEJ?elwulf waes Ecgbryhting, JEthelwulf was son

of Ecgbryht. The old Saxon title Jtf&eling, for the Crown Prince / was

thus formed, as it were the son of the JESel or Estate. About the year 1300,

Robert of Gloucester considered this word as needing an explanation: Ac be

gode tryw men of be lond wolde abbe ymade kyng pe kunde eyr, be 3onge chyld,

Edgar Abelvng. Wo so were next kyng by kunde, me clupeb hym Athelyng. pervor

me clupede hym so, vor by kunde he was next kyng. Ed. Hearne, i. 354.

Translation. But the good true men of the land would have made king the

natural heir, the young Chyld, Edgar Atheling. Whoso were next king by

birthright, men call him Atheling: therefore men called him so, for by birth

he was next king. In some of these instances we see -ing added to words

ending in l; and as this repeatedly happened, there arose from the habitual

association of this termination with that letter a new and distinct formative

in -ling, as changeling t |

|

|

|

|

|

301

darling, failing, firstling, fondling, fotmdling, gosling, hireling,

nestling, nurseling, seedling, stripling, starveling, underling. 377. comlyng.

Hyt seme|) a gret wondur hou3 Englysch pat ys pe burp-tonge of Englyschemen

"j here oune longage "J tonge ys so dyvers of soon in pis ylond, ~\

the longage of Normandy ys comlyng of anoper lond, ~\ hap on manere soon

among al men pat speke]> hyt ary3t in Engelonde. John Trevisa, Higdens

Polychronicon, a.d. 1387. weakling. His baptisme was hastned to prevent his

death, all looking on him as a weakling, which would post to the grave.

Thomas Fuller, Franciscus Junius in 'Abel Redevivus,' 1 651. Even this

secondary formative is of high antiquity, and its standing in our language is

only imperfectly indicated by the observation that it is in German as in

English far more frequent than its primary in -ing. The word silverling in

Isaiah vii. 23 is after Luther's (Stlkrling. Here we must also include the

abstract substantive in -ing, Saxon -ung, as blessing bletsung, twinkeling:

and two which are oftener seen in the plural, innings, winnings. The new

ideas of ' peace, retrenchment, and reform ' got their innings. and amid much

struggle, and with a few occasional episodes, have ruled the national policy

from 1830 till 1875. W. R. Greg, Nineteenth Century, Sept. 1878; p. 395

This -ing (-ling) originally signifies extraction, paternity and descent. It

has figured very largely in names of places, as Reading, Sandringham,

Fotheringhay. In such instances it is sometimes patronymic, that is to say,

it was the name of a family from a common ancestor; and sometimes merely

connective with the locality, as we might say 'he of 'the man of/ It slid

into a diminutival function in many instances: of which below, 377. 319. In

-er Saxon -ere; bcEcere baker, boceras Scribes in the Gospels, literally

bookers. From this source we have |

|

|

|

|

|

302

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. also ale-conner, binder, dealer, ditcher, fiddler,

fisher, fowler, grinder, harper, hater, listener, miller, -monger, runner, skipper,

walker, Webber. The area of this termination was vastly enlarged by the

confluence of the French -ier, 338; and now it is one of our most apt and

ready formations: ■ user, believer. Cromwell was

not an ordinary Puritan, and is not to be mixed up with his class. He is a

man sui generis He rises out of the Puritanical movement, and receives its

mould, but he is a user of Puritanism full as much as, and rather more than, he is a believer in

it. J. B. Mozley, Essays, i. 251; ' Carlyle's Cromwell.' It is this -er

which we see in such descriptions as Londoner, Northerner, Southerner. It was

necessary to illustrate my method by a concrete case; and, as a Londoner

addressing Londoners, I selected the Thames, and its basin, for my text. T.

H. Huxley, Physiography, p. viii. 320. -ness, from -nis or -nes, which in

oblique cases made -nesse; and this oblique form it was that became

traditional, and that explains the double-s in present orthography. We can

analyze -nis into n-is, the is being the original formative, M.G. -assus,

while n is an attachment like l in -ling. In the Mcesogothic Lord's Prayer

(15) we see thiudin-assus, and the formative is assus. The frequency of a

similar contact with n seems first to have made ness a formative; but its

attraction proved so powerful that it everywhere superseded the pure form.

Such a diversion intimates that the new form approved itself to the mind of

the speakers, and brought more satisfaction than the old. Grimm bewails this

seduction of the speech-genius from the true path; but he admits that the

error, as he calls it, pervades the earliest Old High German remains. The

avidity of this acceptance I explain by reference to Ness a headland. That

particular explanation may or may not be the real one; but these |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES SAXON FORMS. 303 transitions do not take place without some

such mental connivance, though the mind be little conscious of its part. This

formative is unknown in the Scandinavian languages. Examples: awkward?iess,

blindness, carelessness, consciousness, darkness, emptiness, fullness,

goodness, heaviness, indebtedness, meanness, peaceableness, readiness,

supple?iess, usefulness, weariness, wilderness, witness. Illustrations:

highmindedness, dejeciedness, contentedness. He that cannot abound without

pride and high-mindednesse, will not want without too much dejectednesse . .

. Frame a sufficiency out of contentednesse Richard Sibs, Seniles Conflict,

ch.x. ed. 1658. composedness. Spiritual composedness and sabbath of spirit.

I'd. ever lasting ness. But felt through all this fleshly dress, Bright

shoots of everlastingness. Henry Vaughan (1621-1695), The Retreat.

carelessness. The sole explanation of incongruities in Shakespeare is to be

found, I believe, in that sublime carelessness which is characteristic of the

genius of this wonderful man. Sir Henry Holland, Recollections of Past

life, ch. ix. The plural -nesses is comparatively rare. The sense being

mostly abstract in this group, the plural is the less called for. If however

the sense is concrete, the plural is used commonly, as witnesses. Even in

abstract words it is also employed, but there is something of demonstration about

it. Jeremy Taylor has darknesses, and Paley has consciousnesses: . . .

illuminations, secret notices or directions, internal sensations, or

consciousnesses of being acted upon by spiritual influences, good or bad.

Evidences i. 2. 1. Dr. Mozley has grotesquenesses, coolnesses: In the midst

of enemies, Irish and English, Court treacheries and coolnesses, Strafford

depended solely upon Laud, and no one other support Archbishop Laud (1S45)

in Essays (1878) p. 201. |

|

|

|

|

|

304

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. In such instances, there is something pronounced, there is

just a touch of demonstrativeness. 321. There has been a period, dating from

the sixteenth century, in which this formative has been less in vogue, whilst

the Latin -alion has prevailed; but rivalry between forms is often smoothed

into cooperation, in a language that loves the breadth of duplicate

expression. Thus we see -ness and -alion yoked amicably together, as More

studious of unity and concord than of innovations and new-fangleness.

Common Prayer, Of Ceremonies. There is sometimes a touch of humour in -ness:

What an unusual share of somethingness in his whole appearance! Oliver

Goldsmith, Citizen of the World, Letter xiv. Of late years -ness has been

much revived, and has furnished some new words, as indebtedness. Indeed the

form has become a modern favourite, and many a new turn of speech has been

made with it. In the bold novelty of some of them we may almost trace a

spirit of rebellion against conventionality. inwardness. Nor Nature fails my

walks to bless With all her golden inwardness. James Russell Lowell.

hopefulness, belieffulness. And there is a hopefulness and a belieffulness,

so to say, on your side, which is a great compensation. A. H. Clough to R.

W. Emerson, 1853. missionariness. It is, I think, alarming peculiarly at

this time, when the female inkbottles are perpetually impressing upon us

woman's particular worth and general missionariness to see that the dress

of women is daily more and more unfitting them for any mission or usefulness

at all. Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing. norihness. Long lines of

cackling geese were sailing far overhead, winging their way to some more

remote point of northness. Dr. Hayes, Open Polar Sea, ch. xxxv. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES SAXON FORMS. 305 322. As a consequence of its revived

popularity, it is now frequently substituted for French or Latin terminations

of like significance, and this even in words of Romanesque material. A lady

asked me why the author wrote effeminateness and not effeminacy in the

following passage. 1812, June 17th. At four o'clock dined in the Hall with De

Quince v who was very civil to me, and cordially invited me to visit his

cottage in Cumberland. Like myself, he is an enthusiast for Wordsworth. His

person is small, his complexion fair, and his air and manner are those of a

sicklv and enfeebled man. From this circumstance his sensibility, which I

have no doubt is genuine, is in danger of being mistaken for effeminateness.

Henry Crabb Robinson, Diary, vol. i. p. 391. Indeed -cy and -ness are good

equivalents, and hence they are often seen coupled or opposed, as decency and

cleanliness. Decency must have been difficult in such a place, and cleanliness

impossible. James Anthony Froude, History of England, August, 1567. The

above terminations are of immeasurable antiquity, and we are not in a

position to say whether they were ever anything more than terminations,

whether they ever existed as independent words. But in the instances which

follow, -dom, -red, -lock, -hood, -ship, -ric, we know that the terminations

were once separate words, and the earliest examples were therefore once in

the condition of compounds, in which the second part was as intentionally

selected for the occasion as the first. But this condition has long ago

passed away, and the second part has become a traditional appendage to the

first, while the two together represent an idea which the mind no longer

analyzes. 323. The collective or abstract -dom is found in all the dialects

except the Mcesogothic. It seems to have originally meant distinction,

dignity, grandeur, and so to have been chosen to express the great whole of

anything. As a separate word it became doom, meaning authority and judgment.

x |

|

|

|

|

|

306

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. Examples: Christendom, heathendom, kingdom, martyrdom,

serfdom, sheriffdom, thraldom, wisdom. Altered form: halidam or halidame.

The Germans make a variety of words with this formative, as Stftfjum

bishopdom; 3fteicfytf)uni richdom. This form has recovered a new activity of

late years, and it is now highly prolific. We meet with such new examples as

beadledom, fabledom, prigdom, Saxondom, scoundreldom, rascaldom. Saxondom.

How much more two nations, which, as I said, are but one nation; knit in a

thousand ways by nature and practical intercourse; indivisible brother

elements of the same great Saxondom, to which in all honorable ways be long

life! Thomas Carlyle, in Forster's Life of Dickens, ch. xx. rascaldom. I

doubt very much indeed whether the honesty of the country has been improved

by the substitution so generally of mental education for industrial; and

the three R's,' if no industrial training has gone along with them, are

apt, as Miss Nightingale observes, to produce a fourth R of rascaldom. J.

A. Froude, at St. Andrew's, March, 1869. prigdom. Well, and so you really

think, that my son will come back improved; will drop the livery of prigdom,

and talk like other people. The Monks of Thelema (1878) ch. iv. The value

of the formative has altered in the case of Christendom. This word is now

used to signify the geographical area which is peopled by Christians; but in

the early use it meant just what we now mean by Christianity, the profession

and condition of a Christian man. It is early days to find the modern sense

in Chaucer And ther to hadde he ryden no man ferre, As wel in cristendom as

hethenesse, Prologue, 49; and rather belated to find the elder sense in

Shakspeare. In the graphic dialogue about the new fashions fresh from France,

the lord chamberlain says |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES SAXON FORMS. 307 Their cloathes are after such a Pagan cut

too't, That sure th'haue worne out christendorne. Henry VIII, i. 3. 15. 324.

Substantives in -red are, and always were, but few. The formative answers to

the German xatt) in <$tixatt), marriage, originally meaning design, but in

the formative having only the sense of condition. It seems to be the same as

the final syllable in the proper names Alfred, Eadred, JEpelred. Of this

formation I can only produce two words that are still in current use, unless

we may place hundred here. Examples: hatred, kindred. In the fourteenth

century we meet with gossipred. But the enmity between the 'English by blood'

and 'English by birth ' still went on, and the former married with the Irish,

adopted their language, laws, and dress, and became bound to them also by '

gossipred ' and ' fosterage.' W. Longman, Edward the Third, vol. ii. p. 15.

The words of this formation seem to be specially adapted for the expression

of human relationships, whether natural, moral, or social. This is the case

with the three already instanced, as well as with others belonging to the

Saxon stage of the language. We must not omit the word neighbourhood, which

is one of these terms of social relationship, and which was originally '

neighbour;-^/ as we find it far into the transition period. Mon sulSe his

elmesse ]>enne he heo gefe5 swulche monne Se he for scome wernen ne mei

for ne3eburredde. Old English Homilies, p. 137. Man sells his alms tuhen he

givelh it to such a man as he for very shame cannot warn off [ = decline

giving to~\ by reason of the ties of neighbour' hood. 325. -lock, -leche,

-ledge. These are very few now, and were not numerous in Saxon, where the

termination was in the form -lac: as brydlac marriage, gicSlac battle,

reaflac spoil, scinlac sorcery. The word lac here is an old word x 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

30 8

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. for play, and still exists locally in lake-fellow for

play-fellow. To lake is common in Cumberland and Westmoreland in the sense of

' to play.' * Examples: ivedlock; and in an altered form, knowledge.

knowleche. But and yf he wolde haue comen hyther, he myght haue ben here, for

he had knowleche by the kynges messager. William Caxton, Reynart (1481), p.

58, ed. Arber. 326. -hood was an independent substantive in Saxon literature,

in the form of had. 32. This word signified office, degree, faculty, quality.

Thus, while the power and jurisdiction of a bishop was called ' biscopdom '

and ' biscopric,' the sacred function which is bestowed in consecration was

called '■ biscophad.' The verb for ordaining or

consecrating was one which signified the bestowal of had, viz. 1 hadian.'

Examples: boy hood, brotherhood, childhood, falsehood, hardihood,

likelihood, livelihood, maidenhood, manhood, sisterhood, widowhood. A secondary form is -lied, which

in Godhead is obscured by an unmeet orthography, so that the meaning Godhood

is not quite plain 2 . Both forms are found in Chaucer, as chapmanhode {Man

of Lazves Tale, stanza 2), goodelyhede {Blaunche 829). In Spenser it is -hed

or -hedd, as in his description of a comet: dreryhcdd. All as a blazing

starre doth farre outcast His hearie beames, and flaming lockes dispredd, 1

Guthlac was not only a word for battle, but was also a man's name; tc wit, of

the Hermit of Croyland. Also warlock may be regarded as one of this class, at

least by assimilation. It is probably a modification of the Saxon ivcEr-loga,

which Grein eloquently translates vsritatis uifitiator, anc which was

applicable to almost any sort of intelligent being that was perfidious, and

under a ban, and beyond the pale of humanity. 2 It were a merit, if any had

the courage, to write Godhcd. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES SAXON FORMS. 309 At sight whereof the people stand aghast; But

the sage wisard telles, as he has redd, That it importunes death and dolefull

dreryhedd. The Faery Qu eerie, iii. I. 1 6. boimtihed. She seemed a woman of

great bountihed. Id. iii. I. 41. The word livelihood merits notice by itself.

It has been assimilated to this class by the influence of such forms as

likelihood. The original Saxon word was lif-ladu (vitae cursus), the course

or leading of life. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries it was written

liflode, and was the commonest word for 'living' in the sense of means of

life, where we should now use the (unhistorical) form livelihood. This

formative is represented in German by -l)eit, as eerr genuine, Gclubcit

genuineness; or -feit, as ettel idle, (Sttelfeit frivolity, vanity. 327.

-ship is from the old verb sceapan, to shape; and indeed it is the mere

addition of the general idea of shape on to the noun of which it becomes the

formative abstract. It corresponds to the German -fctnift, as ©efell

companion, ©efeflfdjaft society. Examples: authorship, doctorship,

fellowship, friendship, lordship, ladyship, ownership, proctorship,

trusteeship, workmanship, worship ( = worth-ship). Illustrations: The

proctorship and the doctorship. Clarendon, History, i. § 189. Trusteeship

has been converted into ownership. Edward Hawkins, Our Debts to Ccesar and

to God, 1868. The Dutch form is -schap, as in Landschap (Germ. &mbfdjaft)

a word which we have borrowed from the Dutch artists, and made into

landscape. 328. The form -ric is an old word for rule, sway, |

|

|

|

|

|

310

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. dominion, jurisdiction. We have but one word left with

this formative, viz. bishopric. There used to be others, as cyneric, like the

German JtonigreicJ); but we now say ' kingdom.' They would not regard the

last syllable in this word as a formative, but as an independent substantive

Sftetcfy, and they would regard ^onigreid) as a compound. We cannot so regard

bishopric, simply because we have lost ric as a distinct substantive; but

when the word bishopric was first made, it was made as a compound. The same

is true of all this group of substantives in -dom, -hood, -lock, -red, -ship,

that they were originally started as compounds; but the latter member having

lost its independent hold on the speech, it has come to be regarded as a mere

formative attached to the body of the word as a significant termination. At

the end of the Saxon list it seems most natural to' mention a few words which

make their appearance for the first time with the modern English language,

and of which the origin is obscure. Such are boy, girl, pig, dog. Piers

Plowman has boy, and so has Chaucer A slier boy was non in Engelonde.

Canterbury Tales, 6904. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 311 occurs in every chief language of Europe, is

from Old High Dutch ward, and corresponds to the last syllable in the Saxon

name Edward. In our form ivarden, we cast off the French guise of the first

syllable, but retained the Romanesque termination, Latin -ianus, French -ten.

The French garden is radically one with the English yard; the French range

with the English rank: and so in many other instances. Some of our French

substantives are hard to classify, because their formatives are obliterated \

as anguish, aunt ante (amita), chief chef (caput), court, dame, depot,

estate, face, grace, image, justice, page, peace, peril, place, pride, ruin,

rule, vial, virtue, vow vceu. The French substantival forms are: -y -le -el

-er -ery -our -son, -shion, -som -ment -et, -ette, -let -age, -enger -or,

-our, -er -er, -or, -ar -ier, -yer, -er, -eer -ee -ard -on, -ion, -oon -ine,

-in -ure -ice, -ise, -esse -ity, -ty -acy -ain, -aign -ade, -ad |

|

|

|

|

|

312

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. y, French -ie, Latin -ia: alchemy, barony, clergy,

company, courtesy, envy en vie (invidia), felony, glory, jealousy, monarchy,

policy, philosophy, story, vilany. This is a very pervading form, which often

adds a finishing tip to other Romanesque formatives, both of French and Latin

complexion: as in -ery, -acy, -ency. 331, 350, 356. It is also an absorbing

form, drawing into itself other forms besides the above: thus jury juree, and

-ity, 349, -osity, 357. Many names of countries belong here: Brittany,

Burgundy, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Lombardy, Normandy, Picardy, Saxony,

Tartary, Turkey. Others of the same type, but later known to us, keep the

Latin form: as, Albania, Armenia, Bavai'ia, Bulgaria, Dalmatia, Mesopotamia,

Prussia, Roumania, Russia, Scandinavia, Slavonia, Wallachia. One country at

least takes both forms: we have Araby in poetry and Arabia in prose. This

termination was disyllabic, not only in Latin, and in French (where it still

is so obscurely), but also in early English. The French accent being on the

i, as compagnie^ it was easy for the -e to evaporate, leaving only the simple

sound represented by -y. None perhaps are more distinctly French in look than

those in -le, after French -le, -aille; Latin -ela, -alia, -ulus, -ula,

-ulum. Examples: angle, battle, bible, candle (candela), cattle, couple

(copula), fable (fabula), marble, miracle, people peuple, stable, table,

uncle oncle (avunculus). Almost blending with these, but still

distinguishable, are those in -el an old diminutive, Latin -ellus, Italian

-etlo, Old |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 313 French -*/, Modern French -eau, fern. -elk.

The diminutival power is rather effete, but may still be perceived in some of

the instances. Examples: bowel, bushel, chapel, cockerel, damsel, morsel,

pommel, sachel sacculus, vessel. The tendency of these to lose themselves in

the former group is seen in castle castellum, mantle O. Fr. mantel, Mod. Fr.

manteau, Ital. mantello. 330. The next form is interesting, although it has

but a feeble hold on the modern language, and never was much more than a

legal technicality. -er is a French infinitive become substantive. We are

familiar with the French infinitive in such a law phrase as 'oyer and

terminer'; but the following are become substantives attainder, cesser,

demurrer, disclaimer, misnomer, rejoinder, remainder, surrender, tender,

trover, user, waiver. cesser. I assure you we are all happy to hear of your

recovery and cesser of pain. Lord Brougham to Matthew Davenport Hill, 1831;

Memoir of M. D. Hill, p. 109. user. Several of the commons proposed to be

enclosed are in the neighbourhood of large towns, and one of them, embracing

the Lizard Point and Kynance Cove in Cornwall, comprising scenery of unusual

beauty. The practical effect of the enclosures would be to prevent that

public user of the commons which has hitherto existed, without making

anything like an adequate reservation in lieu of it. August 9, 1870.

waiver. Therefore the British Commissioners regarded them as waived. They

recorded the waiver, and informed the Government of it at the time . , . .

And because the American Commissioners did not formally present them a second

time, he concluded that they were waived, and he telegraphed to his

Government of the waiver. June 6, 1872. 331. Among the most thoroughly

domesticated of the French forms are those in |

|

|

|

|

|

3H vn -

THE NOUN GROUP. -ry or -ery, French -erie, as in Jacquerie, gendarmerie:

ancientry, battery, bravery, cavalry, chapelry, dea?iery, fishery, foppery,

gentry, heraldry, hostelry, husbandry, huswifry Sh, imagery, Jewry,

machinery, mockery, nunnery, nursery, palmistry, piggery, poetry, pottery,

poultry, rookery, sorcery, spicery, swannery t trumpery tromperie, villagery,

witchery, yeomanry. mockeries. I think we are not wholly brain, Magnetic

mockeries. In Memoriam, cxix. Shrubbery is from the old homely word scrub

in the sense which it bears in ' Wormwood Scrubs,' and in the following

quotation: It [the barony of Farney] was then a wild and almost unenclosed

plain, and consisted chiefly of coarse pasturage interspersed with low alder

scrub. W. Steuart Trench, Realities of Irish Life, p. 66. From this French

form the Germans have borrowed their -eret as ©roJHpredjerei tall talk,

rodomontade, Surtftcrei jurisprudence. Some of these words, once borrowed

from French, are now more English than French. Thus poeterie was already for

Cotgrave in 1 6 1 1 'an old word '; that is to say, old in French; and now

it is not a French word at all. It is entirely superseded by a Greek word

poe'sie. It survives only in our poetry, and this has become a distinctively

English word. Another word that bears our stamp, is fairy. This was

originally fe'erie, the collective noun to the French fee, as those little

folk are still called across the Channel, but we gradually passed from such

expressions as land of faerie and queene of faerie, to make fairies the

modern substitute for the native elves. For a Greek -cry see 364. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 315 In -our, from O. French -our, New French

-eur, Latin -or, -oris: as clamour, honour, labour. 332. In -son, -shion, or -som,

after the French -son from the Latin nouns in -tio, -tionis. The termination

-son represents the Latin accusative case. Examples: advowson advocationem,

arson, benison benedictionem, comparison comparationem, fashion factionem,

garrison Fr. garnison, lesson lectionem, malison maledictionem, orison

orationem, poison potionem, ransom redemptionem, reason rationem, season

sationem, treason traditionem, venison venationem. The form -sion must also

be placed here, after the French from the Latin -sionem; as mansion, passion,

pension. Foison is an interesting word of this class. It is now out of use,

but it occurs in Chaucer, Spenser, and Shakspeare. It signified abundance,

copiousness; and represented fusionem the accusative of fusio, which was used

in a sense something like our modern Latin word ' profusion.' The modern

Italian has the substantive fusione. It is a very frequent word in Froissart,

as grand 1 foison de gent, a great multitude of people. The following

passage, from a fifteenthcentury description of the hospitality of a

Vavasour, exemplifies the use of this word. Sirs, seide the yonge man, ye be

welcome, and ledde hem in to the middill of the Court, and thei a-light of

theire horse, and ther were I-nowe that ledde hem to stable, and yaf hem hey

and otes, ffor the place was well stuffed; and a squyer hem ledde in to a

feire halle be the grounde hem for to vn-arme, and the Vavasour and his wif,

and his foure sones that he hadde, and his tweyne doughtres dide a-rise, and

light vp torches and other lightes ther-ynne, and sette water to the fier,

and waisshed theire visages and theire handes, and after hem dried on feire

toweiles and white, and than brought eche of hem a mantell, and the Vauasour

made cover the tables, and sette on brede and wyn grete foyson, and venyson

and salt flessh grete plente; and the knyghtes sat down and ete and dranke as

thei that ther-to haue great nede. Merlin, Early English Text Society, p.

517. 333. In -ment. From the Latin -nwitum, as frumentum, |

|

|

|

|

|

31 6

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. jumentum. In the early time this form figured much more

largely in French than in English. For example, we have not and never had in

English the two Latin words nowquoted. But the French have both fromenf and

jument. We may add, that words of this termination were most numerous with us

during the period when the French influence was most dominant, and that since

that period many of them have grown obsolete. Examples: accomplishment,

advancement, amendment, battlement, cement, chastisement, commandment,

deportment, detri?nent, development, element, enchantment, engagement,

firmament, habili7nent, improvement, instrument, judgment, moment, ointment,

ornament, parlement, pavement, payment, regiment, sacrament, savement,

sentiment, tenement, testament, torment, tournament, vestment. sentement =

taste, flavour. And other Trees there ben also, that beren Wyn of noble

sentement. Maundevile, p. 189. fir?nament, compassement. For the partie of

the Firmament schewethe in o contree, that schewethe not in another contree.

And men may well preven by experience and sotyle compassement of Wytt that .

. . men myghte go be schippe alle aboute the world. Maundevile, p. 180. In

the following quotation, intendiment means understanding, intelligence, from

the French entendre, to understand. Into the woods thenceforth in haste shee

went, To seeke for herbes that mote him remedy; For shee of herbes had great

intendiment. The Faery Queene, iii. 5. 32. encroachment. One of the most

noticeable facts in literature is the gradual encroachment of prose upon

poetry a change which has been going on from the first, and of which

evidently we do not yet see the end. John Conington, The Academical Study

of Latin. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 317 In some modern words it seems to be rather

an English than a French form; thus we have made the French embarras into the

English embarrassment. The revived interest in older formatives which marks

our time has brought this also into fresh notice, and has caused its

word-painting power of picturesqueness to be appreciated. In a recent story,

the heroine has a ' face full of dimplements.' 334. In -et. A French

diminutive form, masculine, Italian -etto. Examples: bouquet, budget,

cricket, crochet, cygnet, facet, floiveret, gibbet, hatchet, isl-et,ju?iket,

tatchet, pocket, riiul-et, signet, socket, ticket, trumpet, turret. Lynchei

is a local word of Saxon origin which has taken this French facing. In the

neighbourhood of Winchester and elsewhere along the chalk hills, it signifies

bank, terrace; and it has been applied to those ledges which have the

appearance of raised beaches. It is the old Saxon word Mine, frequently used

in Saxon charters for an embankment, artificial or natural. So it gets

attached to frontier wastes, as in the case of the Links of St. Andrews,

Malvern Link. In Jenning's Glossary of the West of England, linch is defined

as ' A ledge; a rectangular projection/ and here we have the form which was

frenchified into lynchet. And -ette, Italian -etta, the feminine of the

above. Examples: coquette, etiquette, marionette, mignonette, pat ette,

rosette, vignette, wagonette. We have adopted etiquette a second time. Our

first reception of it has degenerated into ticket, which comes under the form

last mentioned. This diminutival form -et, -ette, was in old French often

superimposed upon the effete diminutival -el, 329; and hence resulted the

composite termination -let. Examples: armlet, bracelet, branchlet, chaplet,

frontlet, gauntlet, kinglet, ringlet, tr outlet. |

|

|

|

|

|

31 8

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. branchlet. I have found it necessary to make a

distinction between branches and branchlets, understanding by the latter term

the lateral shoots which are produced in the same season as those from which

they spring. JohnLindley, A Monograph of Roses (1820), p. xxi. islet,

ringlet. Nor for yon river islet wild Beneath the willow spray, Where, like

the ringlets of a child, Thou weav'st thy circle gay; John Keble, Christian

Year, Tuesday in Easter Week. 335. In -age, a French form from Latin -aticam:

as average, baggage, bondage, carnage, carriage, cottage, damage, espionage,

foliage, herbage, language, lineage, marriage, message, passage, plumage,

poundage, tonnage, vicarage, village, voyage. These words had for the most

part an abstract meaning in their origin, and they have often grown Vnore

concrete byuse. The word collage, as commonly understood, is concrete, but

there was an older and more abstract use, according to which it signified an

inferior kind of tenure, a use in which it may be classed with such words as

burgage, soccage. The following is from a manuscript of the seventeenth

century. The definition of an Esquire and the severall sortes of them

according to the Custome and Vsage of England. An Esquire called in latine

Armiger, Scutifer, et homo ad arma is he that in times past was Costrell to a

Knight, the bearer of his sheild and helme, a faithful companion and

associate to him in the Warrs, serving on horsebacke, whereof euery knight

had twoe at the least in attendance upon him, in respect of the fee, For they

held their land of the Knight by Cottage as the Knight held his of the King

by Knight service. Ashmole MS. 837, art. viii. fol. 162. A beautiful

abstract use of the word personage, in the sense of personal appearance,

occurs in The Faery Queene, iii. 2. 26: |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 319 The Damzell wel did vew his Personage.

Carriage now signifies a vehicle for carrying; but in the Bible of 161 1 it

occurs eight times as the collective for things carried, impedimenta. In

Numbers iv. 24 it is a marginal reading for ' burdens/ which is in the text.

In Acts xxi. 15, 'We tooke vp our cariages ' is in the Great Bible (1539) '

we toke vp oure burthenes/ and in the Geneva version (1560) 'we trussed vp

our fardeles.' The abstract glides easily into the collective, and this is

seen in many of the instances, as baggage, carnage, foliage, herbage,

plumage. I asked a girl in Standard III, the lesson being Campbell's Parrot,

what plumage meant? She answered, ' A nice lot of feathers, Sir/ 336. Next to

-age we naturally come to the form -ager, as in the French passager,

messager. Above, 71, we find messager in an English letter of the year 1402.

It has been altered in English to -enger, as passenger, messenger; and

-inger, as harbinger, porringer, pottinger, wharfinger. Wallinger is the name

of a class of labourers in the salt-works at Nantwich, and it may perhaps be

connected with Saxon weallan to boil. Mur inger is the title of the officers

who are charged with the repairs of the walls at Chester, and it may be seen

on a tablet over an archway near the Water Tower. In the fourteenth century

there was a public officer known as the King's aulneger, who was a sort of inspector

of the measuring of all cloths offered for sale, and his title was clerived

from the French aulne an ell, aulnage measuring with the ell-measure. And

here belongs also that great mediaeval word danger, as if danager, from dan

dominus, as in 'Dan Chaucer.' It was used to signify lord's rights, lordship,

sway, mastery. In the Romaunt of the Rose 3015 it is a man's name: |

|

|

|

|

|

5 2 o VII.

THE NOUN GROUP. But than a chorle, foul him betide, Beside the roses gan him

hide, To keepe the roses of that rosere, Of whom the name was daungere: This

chorle was hid there in the greves, Covered with grasse and with leves, To

spie and take whom that he fond Unto that roser put an hond. ' 337 In -or,

-our, -er, Old French -eor (disyllabic), New French -eur, from Latin -tor

-oris: as, chanter chanteor (cantator), emperor empereor (imperator),

govemour (gubernator), traitor (traditor), saviour salveor (salvator). The

form saviour is intelligible not from New French sauveur, but from the Old

French salveor trisyllabic \ 338 In -er, -or, -ar, French -ier (Latin

-arius); as, bachelor bachelier (baccalarius), butcher, carpenter, Fletcher,

gardener, arocer, usher huissier (ostiarius), vintner. This French -ier is '

perhaps the most productive ' of all the French noun- ■

forms 2 It is the constant type of word for expressing a man's trade, and in

this function it sustained and enlarged the Saxon -ere, 319. In the Prologue we have four

of them in two lines: An Haberdasshere and a Carpenter, A Webbe, a Dyere,

and a Tapycer. In French this -ier was moreover the prevalent type for

tree-naming; but this has passed into English, as far as I remember, in only

one instance, poplar peuplier. 339. -ier, -yer, -er, from French -fere, the

fern, of the above; as, barrier barriere, prayer priere, river riviere. In

-or, -er, from French -oir (Latin -orius); as, counter comptoir, mirror

miroir, r azor rasoir. ^^ i Friedrich Diez, Grammatik der Romanischen

Sprachen, ii. 49, 35° (e *- A u*uste Brachet, Grammaire Historic p. 2 7 6 (p.

184 of Mr. Kitchin's Translation, Clarendon Press Series). |

|

|

|

|

|

1. SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 32 1 Here we

may observe in a series of examples how a variety of original forms run down

into -er. And there are more than these. Thus, from French -aire (Lat.

-arium), as dower douaire (dotarium); and -eoi're, as manger mangeoire. This

became an absorbing type. Saxon words of like import but unlike form were

drawn into it; thus cuma became comer, hunta hunter. 340. Another form, -eer,

is modern as to orthography, but perhaps it may be the true living

representative of the French -ier, as auctioneer, buccaneer, charioteer,

mountaineer, muleteer, pamphleteer, pioneer, privateer. This form is

sometimes used half-play fully: fellow-circuiteer . The enormous gains of my

old fellow-circuiteer, Charles Austin, who is said to have made 40,000

guineas by pleading before Parliament in one session. Henry Crabb Robinson,

Diary, 18 18. 341. In -ee. This termination is from the French passive

participle. Examples: devotee, feoffee, grandee, grantee, guarantee,

legatee, levee, mortgagee, nominee, patentee, payee, referee, refugee,

trustee. The original passive character of the form still shines out in most

of the examples; and often there is an active substantive as a counterpart.

Thus grantor, grantee; lessor, lessee; mortgagor, mortgagee. Assimilated are

decree decret (decretum), degree; also such names as Chaldee, Pharisee,

Sadducee, Manichee (for which Manichean is now more general), and Yankee.

342. In -ard, -art. Examples: bastard, braggart, buzzard, bustard, coward,

dastard, dotard (Spenser, Faery Queene, iii. 9. 8), drunkard, dullard,

haggard a sort of hawk, laggard, mallard, niggard, pollard, sluggard,

standard, tankard (a little tank, French e'tang, Latin stagnum), wizard. Y |

|

|

|

|

|

322

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. Here should be mentioned also the national designations Nizzard,

Savoyard, Spaniard. In -on, -ion, -oon, French -on, as in macon, mouton,

salon; Latin masculines in -o, -io, genitive onis: balloon, buffoon, capon,

champion, dungeon, escutcheon, falcon, felon, glutton, harpoon, lion, mutton,

pavilion, pigeon, salmon, stallion, saloon. These are to be distinguished

from those in -son, 332, from Latin feminines in -tio, -Horn's. 343. In -ine,

in, after the French from the Latin -inus, -ina. Examples: basin, cousin,

famine, florin, libertine, matins, rapine, resin, routine, ruiti, vermin.

Altered forms: canteen Latin cantina = cellar, curtain, don Latin dominus,

garden jardin, paten, venom venin. 344. In -ure, Latin -ura, as mensura.

Examples: adventure, capture, caricature, censure, culture, departure, embrasure,

expenditure, failure, fissure, furniture, garniture, imposture, indenture,

juncture, manure, measure, miniature, mixture, nature, nomenclature, nurture,

overture, pasture, picture, posture, portraiture, pressure, primogeniture,

procedure, rapture, scripture, seizure, signature, stature, suture, torture,

verdure. Assimilated are leisure, treasure, from the French loisir, tre'sor.

closure. And for his warlike feates renowmed is, From where the day out of

the sea doth spring, Until! the closure of the Evening. The Faery Qjieene,

iii. 3. 27. disclosure. It follows, then, that Man is the great disclosure of

design in Nature; that Man lets out the great secret of the authorship of

Nature; and that Man is the revelation of a God in Nature. J. B. Mozley, 4

The Argument of Design,' Essays, ii. 370. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 323 345. In -ice or -ise: after two or three

various Latin terminations, but typically from -itia. The Romanesque

languages have a double rendering for the Latin -ilia, the first of these

being in Italian -izia, in French -ice or -ise. Examples: avarice, covelise

Spenser, cowardice, foolhardise Spenser, justice, malice, merchandise,

nigardise Spenser Faery Queene, iv. 8. 15, notice, queintise Chaucer, riotise

Spenser. gentrise, covetise. Wonder it ys sire emperour that noble gentrise

That is so noble and eke y fuld with so fyl couetyse. Robert of Gloucester,

p. 46. Franchise was a great word in the French period, and it had a wide

range of significations. Among other things it meant political privilege,

exemption, and also good manners, good breeding, which latter occurs among

the numerous renderings of this word in Randle Cotgrave's Dictionarie of the

French and English Tongves, 1 6 1 1 . franchise. We mote, he sayde, be hardy

and stalworthe and wyse, 3ef we wole habbe oure lyf, and hold our franchise.

Robert of Brunne, p. 155. To this class belonged the French word pentice or

pentise, of which the last syllable had been already before Shakspeare's time

anglicised into ' house/ making a sort of compound, pent-house. We must admit

into this set such words as edifice, prejudice, service, and we cannot make

the Latin termination -itium a ground of distinction in English philology,

where words are assimilated in form. On the confluence of formatives see 339.

346. In the sixteenth century these words were often Y 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

3^4

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. written with a z, and in this we must recognise a

phonetic effort. The French -ise sounded the same as -ice, but English people

gave it a zed-sound. Hence that struggle between the forms -ise, -tee, -ize.

The -ise and -ice are French, the -ize is the insular usage phonetically

written. In the sixteenth century the letter z was favoured by fashion, and

it made a certain inroad, gaining a good many places which were for the most

part phonetically due to it. Queen Elizabeth wrote her name with a z, and

that alone was an influential example. In some cases the fashion disappeared

and left no traces behind it; in other cases it was the origin of the

received orthography. Thus wizard became the recognised form instead of

wisard, which was the spelling of Spenser, as may be seen above, 326. In The

Faery Queene we see this fashion well displayed. There are such forms as

bruze, uze (iii. 5. 33), wize, disguize, exercize, guize (iii. 6. 23),

Paradize (iii. 6. 29), enterprize, e??iprize, arize, devize (vi. 1. 5). So

that there is nothing to marvel at if we find covettse ( = covetousness)

spelt covetize (iii. 4. 7), and the substantive which we now write practice,

written practize: Ne ought ye want but skil, which practize small Wil

bring, and shortly make you a mayd Martiall. iii. 3. 53. This was due to the

Italian example. 347. But there is a further observation to be made

concerning this French substantive form. It seems that we must acknowledge it

to have introduced one of the most extensive modern innovations. It was

apparently the employment of this substantive as a verb that gave us our

first verbs in -ize, and so ushered the Greek -{fn*. An unfamiliar example of

one of these substantives verbally employed may be quoted from the

correspondence of Throgmorton and Cecil in 1567: |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES FRENCH FORMS. 325 They would not merchandise for the bear's

skin before they had caught the bear. Quoted by J. A. Froude, History 0/

England, vol. ix. p. 163. Indeed, there are instances in which the substantive

of this form is no longer known, while the verb is in familiar use. Such is

the verb to chastise (pronounced as if spelt with z), which appears in its

substantive character, equivalent to chastity, in Turbervile, Poem to his

Loue (about 1530): And sooth it is she liude in wiuely bond so well, As she

from Collatinus wife of chastice bore the bell. I imagine the case is the

same with the verbs to jeopardise, and to advertise. Both of these I would

identify with this substantive form, though I am not prepared with an example

of either in its substantive character. But there is perhaps evidence enough

in Shakspeare's pronunciation that the verb to advertise was not formed from

the Greek -ize. In all cases does this verb in Shakspeare sound as adve'rtice,

and never as now advertize: Aduertysing, and holy to your businesse.

Measure for Measure, v. 1. 381. Please it your Grace to be aduertised. 2

Henry VI, iv. 9. 22. For by my Scouts, I was aduertised. 3 Henry VI, ii. 1.

116. I haue aduertis'd him by secret meanes. 3 Henry VI, iv. 5. 9. We are

aduertis'd by our louing friends. 3 Henry VI, v. 3. 18. As I by friends am

well aduertised. Richard III, iv. 4. 501. Wherein he might the King his Lord

aduertise. Henry VIII, ii. 4. 178. In one instance the First Folio has it

with a z, but it makes no difference: |

|

|

|

|

|

J26

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. I was aduertiz'd, their Great generall slept. Troylus

and Cressida, ii. 3. ail. We have still several substantives of the -ice type,

as cowardice, justice, malice, notice; but I cannot call to mind more than

one verb in which this primitive form is retained, and that is the verb to

notice. Where -ment has been added to -ise, the -ise has kept its first

sound, as in advertisement, aggrandisement, chastisei?ient. 348. The second

Romanesque rendering of the Latin -ilia is in Italian -ezza, in French -esse.

So that this form -esse (-ess) is a collateral form to -ice. And the French

language presents us with justice and justesse co-existent in differing

shades of sense. Examples: duresse Spenser, finesse, largess, prowess.

Riches belongs here by its extraction, being only an altered form of

richesse. In grammatical conception it has passed from a singular, to a

plural without a singular. This was one of the effects of centuries of Latin

schooling. The word richesse having been constantly used to render opes or

divitiae, which are plural forms, and being itself so nearly like an English

plural, has thus come to be so conceived of, and written accordingly. Burgess

has taken this shape, but it is from the French bourgeois, and that from the

Latin burgensis. The form -esse, as derived from -issa, and expressive of the

feminine gender, will be found at the close of the section, 384. 349. In the

French reign must be included also the forms in -ity and -ly. In -ity, after

the French -///, with the last syllable accented, because it represents two

syllables of the Latin accusative -iiatem, Italian -ild; as Latin carilatem,

Italian cariid, French char it e', English charity. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVESFRENCH FORMS. 327 Examples: antiquity, benignity, civility,

city civitatem, dexterity, equality, fidelity, gratuity, humanity, integrity

Joviality , legibility, majority, nativity, obscurity, pity pietatem,

posterity, quality, rapidity, sincerity, timidity, urbanity, velocity.

civility, equity, humanity, morality, security. The morality of our earthly

life, is a morality which is in direct subservience to our earthly

accommodation; and seeing that equity, and humanity, and civility, are in

such visible and immediate connection with all the security and all the

enjoyment which they spread around them, it is not to be wondered at, that

they should throw over the character of him by whom they are exhibited, the

lustre of a grateful and a superior estimation. Thomas Chalmers, Sermon V.

(18 19). And -ty, a more venerable form of the same, historically associated

with the legal and political ideas of that early stage of our national life

when French was the language of administration. Examples: admiralty,

casualty, certainty, fealty, loyalty, mayoralty, nicety, novelty, personalty,

realty, royalty, shrievalty, soverainty, spiritually, surety, temporally.

Mayoralty has taken as much as -ally for its suffix, and so grouped itself

with admiralty, royalty, spiritualty, temporalty. And here we may observe by

how slight a variation in form great distinctions are sometimes expressed.

Whereas personalty signifies personal property, chattels, personality

signifies the possession of conscious life: whereas realty signifies real

property, as land or houses, reality signifies the objective existence of

things. The one is after an earlier, the other after a more modern French

form. In some instances we see words changing from one form to another as a

mere fashion, and without any adequate distinction. Thus specialty seems to

be endangered by the tendency to imitate the French specialite' 1 . |

|

|

|

|

|

3^8

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. 350. As also these in -acy from Latin -alia and -aria;

as abbacy ', aristocracy, contumacy, delicacy, efficacy, episcopacy, fallacy,

inadequacy, intimacy, inveteracy, legacy, legitimacy, lunacy, papacy,

primacy, privacy, supremacy suprematie. And those in -ain, -aign, -aigne,

-eign, from French -aine, -aigne, modern -agne, Latin -aneus, as, campaign,

Cockaigne, fountain, mountain, sovereign. 351. Nor may we leave without

recognition those French substantives which we have adopted without any sort of

written modification, as amateur, connoisseur, rendezvous, reservoir. This

would seem to be the place to glance at some substantives which have come to

us through the French, from the southern Romance languages, Provencal or

Spanish. Such are those words 352. In -ade, -ad, which represent the

termination -alus of the Latin participle ambuscade, ballad, balustrade,

barricade, brigade, camionade, cascade, cavalcade, comrade, crusade,

esplanade, fusillade, lemonade, marmalade, masquerade, palisade, parade,

promenade, renegade, salad, serenade, stockade, tirade. The genuine Spanish

form, masc. -ado, fern, -ada, is preserved in Armada, bravado, gambado,

tornado. 353. Round by the Spanish peninsula have also come to us those

English (or rather European) nouns which are derived from Arabic, as admiral,

alchemy, alcohol, alcove, algebra, alkali, almanac, arsenal, azimuth,

caravan, cipher, elixir, exchequer, magazine, nadir, orange, saffron, simoon,

zenith, zero. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES SPANISH, ITALIAN, ARABIC. 329 To these we must add a word,

once celebrated, now obsolete, algorithm, or more familiarly, augrim. Also sometimes,

algorism, after the French algorisme. This Arabic word was the universal term

in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries to denote the science of

calculation by nine figures and zero, which was gradually superseding the

abacus or ball-frame, with its counters. I shall reken it syxe times by

aulgorisme, or you can caste it ones by counters. John Palsgrave, Fre?ich

Grammar, 1530. Nor may we overlook the Italian words that are gradually

winning their way into the list of English substantives. They are almost all

in a direct or indirect sense derived from the artistic terminology of

Italian poetry, or music, or painting, or architecture. Such are campanile,

canto, cantata, cupola, dilettante, extravaganza, finale, forte, fresco,

opera, oratorio, orchestra, piano, sonata, stanza, stiletto, studio,

trombone, virtuoso, violoncello, vista, volcano. vista. It led him on through

stage after stage of his work: a medieval glow terminated the dark laborious

vista; and the plodder's slow subterranean passage had an inward poetry to

illuminate and relieve it. J.B.Mozley, Essays, ' Archbishop Laud,' p. 126.

354. The effect of the French pre-occupation of our language was not limited

to the period of its reign. It also imparted a tinge to the subsequent period

of classic domination. The Latin words that were next admitted into English,

became subject to those French forms which were already familiar among us;

and so much so, that it is rather arbitrary work to pretend to draw the line

of division. |

|

|

|

|

|

330

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES LATIN FORMS. 33 1 but gives the palm to offense, which has

continued to the present day as the correct orthography in French. The -ancy

-eney forms are peculiarly English. Clemency is in French ' clemence/ and

constancy is ' Constance.' The peculiarity arises from our surpassing the

French themselves in our attachment to an old French form -ie, now become^,

of whose various suffixment mention has been made above, 329. The two forms

-ency and -ence are liable to clash in their plurals. It is questioned which

is right, excellences or excellencies. Each has its place; the former in the

sense of abstract quality, the latter for titles of distinction. In our old

writers excellency is the prevalent form, and excellence is a mere duplicate

variety, without a distinct sense. In recent times, excelle?ice has become

dominant in the singular number, but has not yet established its ascendancy

in the plural. In fact the termination -ency is reluctantly yielding to

-ence, and as we look back into our elder literature, we frequently meet with

-ency where -ence is now usual. Thus super inte?ide?icy. Her admonition was

vain, the greater number declared against any other direction, and doubted

not but by her superintendency they should climb with safety up the Mountain

of Existence. Samuel Johnson, The Vision of Theodore. 357. In -osity; as

animosity, curiosity, impetuosity, pomposity, scrupulosity. The forms in -ity

and -ty have been ranked under French products, 349, but osity came of Latin

studies. Its boisterous youth was in the seventeenth century, when several

examples were launched into currency, and soon stranded. Such were

fabulosity, mulier osity, populosity, speciosity. So great a glory as all the

speciosities of the world could not equalize. Henry More, On Godliness, iv.

12. § 4. 358. In -ion, -tion, -ation, -ition, from the Latin -io t |

|

|

|

|

|

3$Z

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. 'alio, -itio, genitive -iom's; as accusation, action,

compassion, contrition, coronation, description, emulation, humiliation, investigation,

occupation, procrastination, region, relation, reputation, situation,

satisfaction, transaction. A very prolific formative. salutation. We behold

men, to whom are awarded, by the universal voice, all the honours of a proud

and unsullied excellence and their walk in the world is dignified by the

reverence of many salutations and as we hear of their truth and their

uprightness, and their princely liberalities, &c Thomas Chalmers, Sermon

V. (1819). This abstract form is capable of a thundering eloquence. When a

new ship of war of the most advanced and formidable class of turret-ships was

announced by the name of ' The Devastation/ it might well be said that the

new cast of name was an apt exponent of the weight of metal by which the

terrors of marine warfare had been enhanced. This is a form upon which new

words have been made with great facility, as witness the off-hand words

savation, starvation. When Mr. H. Dundas used the word starvation in the

House of Commons, it was received with a roar of derision as a north-country

barbarism. J. B. Heard, The Tripartite Nature of Man, p. 83, note. A

gardener once desiring to have his work admired he had been moving some of

the raspberry-canes, to make the rows more regular ' There, sir/ cried he,

' that 's what I call row-tation now!' From this facility it has naturally

followed that many have grown obsolete. Jeremy Taylor uses luxation to

signify the disturbing, disjointing, disconcerting, shocking, of the

understanding: An honest error is better than a hypocritical profession of

truth, or a violent luxation of the understanding. Liberty of Prophesying,

ix. 2. It is a phenomenon which may as well be remarked generally and once

for all, that in the prime of their vigour forms often overpass the area

which they are permanently to |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES LATIN FORMS. 335 occupy. Under each form we might collect a number

of words that have perished, not from age and decay, but just because they

were started rather in obedience to a strong formative impulse of the moment,

than from any occasion the language had for their services l . 359. In -our;

as ardour, creditor, fervour, governour, honour, valour. In this class of

words, derived at secondhand from the Latin words in -or, -ator, -itor, as

fervor, ardor, gubernator, the u is a trace of the French medium. This u has

moreover communicated itself even where there was previously nothing either

of French or of Latin, as in the purely Saxon compound neighbour from neh

nigh, and gebur dweller. A partial disposition has manifested itself to drop

this French u. Especially is this observable in American literature. But the

general rule holds good through this whole series of nouns from the Latin,

that what we call * anglicising ' them, is the reducing of them to a set of

forms which we borrowed originally from French. And thus it is true that the

French influence still accompanies us, even through the course of our

latinising epoch. Latin scholarship was, however, continually nibbling away

at these monuments of the French reign. The forms of many of our Romanesque

nouns were too permanently fixed to be shaken; but wherever the classical

scholar could make an English word more like Latin, he was fain to do it.

Nobody now writes tenour or creditour as in the Bible of 1 6 1 1: and

governour is less usual than governor. |

|

|

|

|

|

334 vu

> THE NOUN GROUP. 360. In -al. This form, which is derived from the Latin

adjectival formative -alts, -ale, has attached itself not only to words radically

Latin, as acquittal, dismissal, disposal, proposal, recital, refusal, rental,

reversal, revival, but also to others which are either French, as avowal,

perusal, rehearsal, survival, or purely English, as uprootal and the familiar

geological term upheaval. approval, refusal. I well remember his

[O'Connell's] smile as he nodded good-humouredly to us as we passed him; and

I must say it was one of approval rather than otherwise at our refusal to do

him homage. W. Steuart Trench, Realities of Irish Life, p. 39. The plural

forms nuptials, espousals, are grammatically imitative of the Latin nuptiae,

sponsalia. A word which does not belong here, but which has assumed the guise

of this set, is bridal, from the Saxon bryd bride, and ealo ale; so that it really

meant the ale or festivity of the bride. One or two other compounds on this

model, such as church-ale, scot-ale, have become obsolete. Another word,

which has an equally deceptive appearance of being formed with the Latin -al

is burial. This is a pure Saxon word from its first letter to its last. The

Saxon form is byrigels, a form which is of the singular number, though it end

with s. The plural was byrigelsas. 361. In -ate, from the Latin -atus,

participle or substantive. Examples: consulate, curate, episcopate,

estimate, opiate, ?nagnate, potentate, probate, syndicate, tribunate. In the

language of chemistry this form has a fixed and definite area assigned to it:

carbonate, chlorate, muriate, sulphate. 362. In -tude, from the Latin

substantives in -ludo, -iudinis. Examples: altitude, beatitude, certitude,

disquietude, exacti |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES LATIN FORMS. $$$ tude, fortitude, gratitude, habitude,

latitude, longitude, magnitude, multitude, solicitude, solitude, turpitude,

vicissitude. habitude. . . . and many habitudes of life, not given by nature,

but which nature directs us to acquire. Joseph Butler, Analogy, i. v. 2

(1736). disquietude. x Look around this congregation. We are all more or less

the children of sorrow. There is not one of us who has not within him some

known or secret cause of disquietude. Charles Bradley, Clapham Sermons, 183

1: Sermon VII. solicitude. The excellent breed of sheep, which early became

the subject of legislative solicitude, furnished them with an important

staple. William H. Prescott, Ferdinand and Isabella, vol. i. p. 29 (ed.

1838). 363. The substantives in -ite must be reckoned anions the Latin ones,

as we received the form through the Latin; but it is Greek by origin. It was

of European celebrity in the middle ages as a class word, especially for

sects and opinions. The followers of the early heresies were often thus

designated, as Monothelites, Marcioniles, Monophy 'sites. Yet the odium which

now attaches to this form cannot have been felt in the sixteenth century, or

our Bible would not shew it so generally as it does, not only in such cases

as Canaanite, Perizzite, Hivite, and Jebusite, but also in Levite,

Ephralhite, Belhlehemite, Israelite. Already, however, at the close of the

seventeenth century, we find the ecclesiastical historian Jeremy Collier

using the term Wicliffists, as if with purpose to avoid writing Wiclifite,

which was the usual form. And thus in our own time the alumni of Winchester

are not indifferent about being called Wykehamites instead of Wykehamists.

The fact is, that with our sensitiveness about religious differences, this

form has become almost odious; and we scruple to quote instances of its

application out of respect |

|

|

|

|

|

$$6

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. for names that may be embodied. Suffice it for

illustration to put down such as Joanna- Southcotites and Mormonites. Still,

there is an historical use in which it is dispassionate enough: Already, in

the short space of six months, he had been several times a Jacobite, and

several times a Williamite. Both Jacobites and Williamites regarded him with

contempt and distrust. T. B. Macaulay, History, 1689, c. xiii. Unaltered

Group. A considerable number of Latin words have been adopted in their

original and unaltered state: abacus, acumen, album, alumnus, animus, apex,

apparatus, arbiter, arcana, area, arena, census, circus, compendium, curator,

deficit, detritus, equilibrium, eulogium, farrago, focus, formula, fungus,

genius, genus, gravamen, herbarium, index, interest, item, maximum, medium-,

memento, memorandum, minimum, minister, minutia, modicum, momentum, odium,

omen, onus, orator, pabulum, pastor, prospectus, radius, regimen, requiem,

residuum, sanatorium, senator, species, specimen, sponsor, squalor, status,

stimulus, stratum, tedium, terminus, tiro, ultimatum, vertex, virus, vortex.

medium. Madame de Stael said, and the general remark is true, ' The English

mind is in the middle between the German and the French, and is a medium of

communication between them.' H. C. Robinson, Diary, vol. i. p. 175.

detritus, stratum. Like the blue and green and rosy sands which children play

with in the Isle of Wight, these tales of the people, which Grimm was the

first to discover and collect, are the detritus of many an ancient stratum of

thought and language buried deep in the past. Max Muller, Chips, Uc. vol.

ii. p. 223. Denuded Specimens. Some Latin words are denuded of their

inflections and stand forth with a Saxon-like simplicity; as adit aditus,

class |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES GREEK FORMS. 337 classis, deposit depositum, exit exitus, herb

herba, orb orbis, plant planta, text textus, unguent unguentum, vest vestis,

victim victima. As a group these naturally represent some of the Latin words

that have been most worn down and therefore oldest in the service of the

English language, and their natural place is at the head of the Latin

section. There they would have been placed, but that the unbroken continuity

between French and Latin forms denied an opening in that place. Greek Forms.

364. Coming now to Greek, we have words denuded of form, as abyss, atom,

epoch, idol, idyl, meteor, myth, 7iymph, ocean, period, syste?n. Here belongs

the important word method, which has played a part in our language. I would

advise you as much as possible to throw your business into a certain method,

by which means you will learn to improve every precious moment, and find an

unspeakable facility in the performance of your respective duties. Letter

from his Mother to Samuel Wesley at Westminster (1709). Forms in -y from

Greek words in -ia and -eia; as academy, agony, irony, pharmacy, rhapsody,

synonymy, tyranny. irony (eipaweta). There was no mockery in Miss Austen's

irony. However heartily we laugh at her pictures of human imbecility, we are

never tempted to think that contempt or disgust for human nature suggested

the satire. threnody {Qp^v^la). We crave not a memorial stone For those who

fell at Marathon: Their fame with every breeze is blent, The mountains are

their monument, And the low plaining of the sea Their everlasting threnody.

The Three Fountains (1869^, p. 100. Z |

|

|

|

|

|

33$

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. A few in -ery from -r,pLov, as baptistery ^airna-T^piov,

cemetery Koiprjrrjpiov, psaltery ^aXrrjpiov. These should be kept distinct

from the French -ery, 331. 365. In -ism from the Greek -107*0$-; as archaism,

absolutism, atheism, catechism, criticism, Darwinism, eclecticism, formalism,

fanaticism, idolism M, materialism, modernism, polytheism, propaga?idism,

scepticism, schism, truism, ventriloquism. This, the most luxuriant of our

Greek forms, began to push itself in Elizabeth's time, but it was still a new

toy in the seventeenth century. In the correspondence between Strafford and

Laud there is a to-and-fro imputation of ' Johnnisms ': Strafford belonging

to St. John's College, Cambridge: Laud to St. John's at Oxford. What means

this Johnnism of yours, till the rights of the pastors be a little more

settled? Well, I see the errors of your breeding will stick by you; pastors

and elders and all will come in if I let you alone. Quoted by J. B. Mozley,

Essays, ' Lord Strafford. ' Scotticism, Protestantism, Catholicism, Presbyter

ianism. For our part, we should say that the special habit or peculiarity

which distinguishes the intellectual manifestations of Scotchmen that, in short,

in which the Scotticism of Scotchmen most intimately consists is the habit

of emphasis. All Scotchmen are emphatic. . . . This habit of emphasis, we

believe, is exactly that perfervidum ingenium Scotorum which used to be

remarked some centuries ago, wherever Scotchmen were known. But emphasis is

perhaps a better word than fervour. Many Scotchmen are fervid too, but not

all; but all, absolutely all, are emphatic. No one will call Joseph Hume a

fervid man, but he is certainly emphatic. And so with David Hume, or Reid, or

Adam Smith, or any of those colder-natured Scotchmen of whom we have spoken;

fervour cannot be predicated of them, but they had plenty of emphasis. In men

like Burns, or Chalmers, or Irving, on the other hand, there was both emphasis

and fervour; so also with Carlyle; and so, under a still more curious

combination, with Sir William Hamilton. . . . Emphasis, we repeat,

intellectual emphasis, the habit of laying stress on certain things rather

than co-ordinating all, in this consists what is essential in the Scotticism

of Scotchmen. And, as this observation is empirically verified by the very

manner in which Scotchmen enunciate their words in ordinary talk, so it might

be deduced scientifically from what we have already said regarding the nature

and effects of the feeling of nationality. The habit of thinking emphatically

is a necessary |

|

|

|

|

|

1.

SUBSTANTIVES GREEK EORMS. 339 result of thinking much in the presence of,

and in resistance to, a negative; it is the habit of a people that has been

accustomed to act on the defensive, rather than of a people peacefully

evolved and accustomed to act positively; it is the habit of Protestantism

rather than of Catholicism, of Presbyterianism rather than of Episcopacy, of

Dissent rather than of Conformity. David Masson, Essays (1856); 'Scottish

Influence in British Literature.' ventriloquism. Coleridge praised '

Wallenstein,' but censured Schiller for a sort of ventriloquism in poetry.

By-the-by, a happy term to express that common fault of throwing the

sentiments and feelings of the writer into the bodies of other persons, the

characters of the poem. Henry Crabb Robinson, Diary, &c, vol. i. p.

396. truism. But, gentlemen, a truism is often thrust forward to cover the

advance of a fallacy. Matthew Davenport Hill, Charge to the Grand Jury,

i860. scepticism. Scepticism, to be worth anything, should be the thoroughly

trained habit of looking deeply into all sides of the question, and not

merely at the outside of one or two. Sir Edward Strachey, Spectator, Dec.

30, 1871. How readily new words are builded on this model may be seen from

the following: The three schools of geological speculation which I have

termed Cata*trophism, Unifcrmitarianism, and Evolutionism, are commonly

supposed to be antagonistic to one another. Address of the President of the

Geological Society, 1869. There is an impression, which is not worthy to be

called a conviction, but which holds the place of one, that the

indirferentism, scepticism, materialism, and pantheism, which for the moment

are so fashionable, afford, among them, an effectual defence against

Vaticanism. W. E. Gladstone to Emile De Laveleye, 1875. The form witticism

seems to imply that -cism has been accepted as the formative, perhaps after

the pattern of Catholic is?n, ostracism, Stoicism. Ben Jonson has ciiycism:

. . . inform'd, reform 'd, and transformed, from his original citycism; . . .

Cynthia's Revels, Act v. Sc. 4 (ed. 1756). * Substantives in -ism are now

formed just as readily as the z 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

340

VII. THE NOUN GROUP. verbs in -ize, from which indeed the noun-form -ism is an

outgrowth. 366. And so is -ist; as atheist, casuist, chemist, dogmatist,

egotist, idolist M, mesmerist, methodist, ministerialist, novelist,

publicist, ritualist, Wykehamist. publicist. The same evening I had an

introduction to one who, in an}' place but Weimar, would have held the first

rank, and who in his person and bearing impressed every one with the feeling

that he belonged to the highest class ot men. This was Herder. The interview

was, if possible, more insignificant than that with Goethe partly, perhaps,

on account of my being introduced at the same time with a distinguished

publicist, to use the German term, the eminent political writer and

statesman, Friedrich Gentz, the translator of Burke on the French Revolution.

H. C. Robinson, Diary. 1801. atheist, pantheist, polytheist. The whole

world seems to give the lie to the great truth of the being of a God; and of

that great truth my whole being is full: so that were it not for the voice

speaking so clearly in my conscience and my heart, I should be an atheist,

pantheist, or polytheist when I looked into the world. J. H. Newman,

Apologia. In these two groups, -ist is the concrete to -ism the abstract, and

both from the Greek. But before the adoption of -ism, the -ist form had its

abstract correlative in the French -ery (331); as casuistry, chemistry,

palmistry, Rami s try Hooker i. 6. margin. 367. But fond as we appear to be

of the Greek verbs in -ize and the Greek nouns in -ism, -ist, we have drawn

very little from a Greek form that lies close beside these. There are Greek

verbs in -aze, and corresponding noun-forms in -asm, -ast, which have been

almost neglected by us. We have a few English nouns In -asm, as chasm,

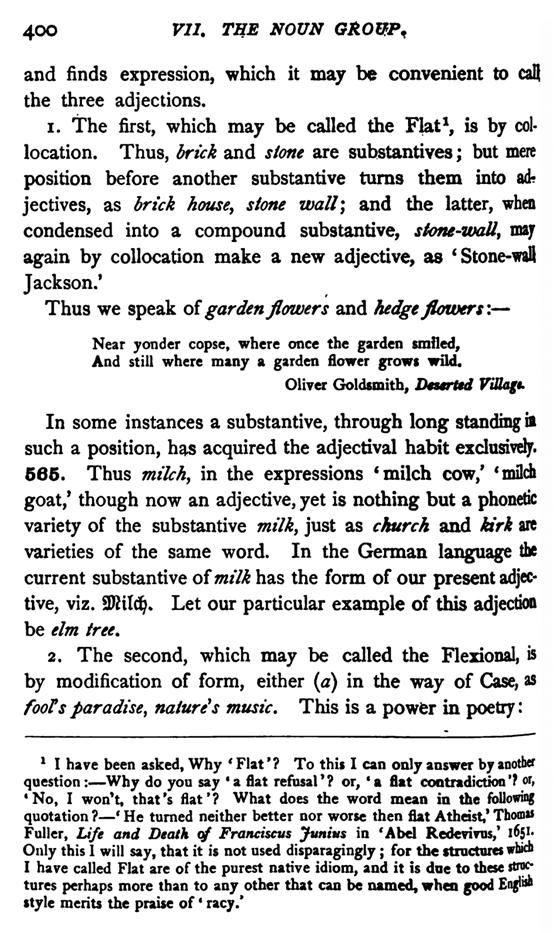

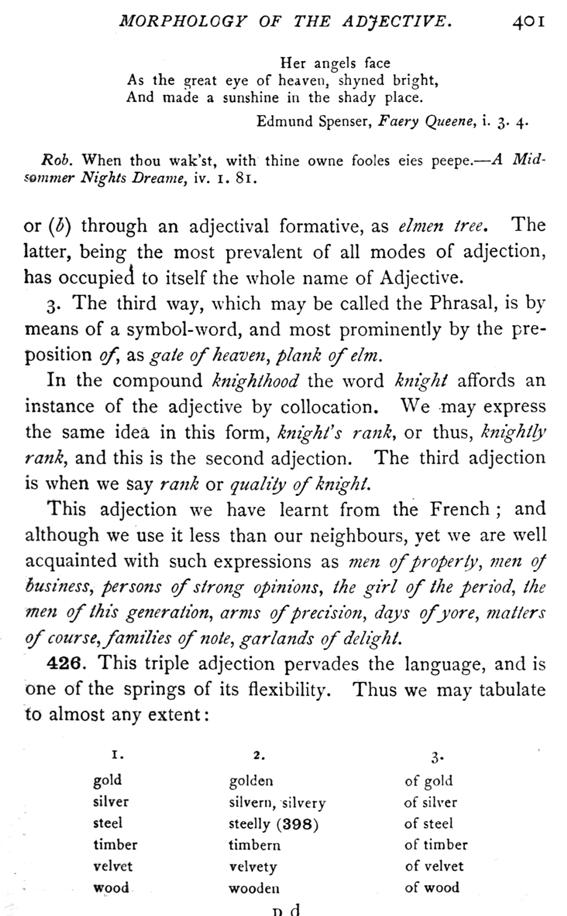

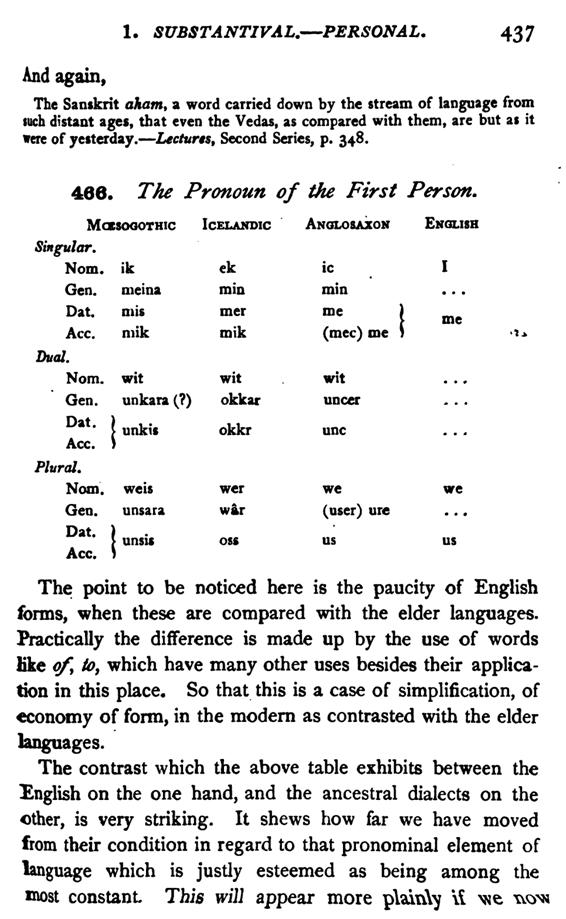

enthusiasm, iconoclasm, pleonasm, protoplasm, sarcasm, spasm. enthusiasm. Wahabeeism