kimkat2125k The Philology

of the English Tongue. John Earle, M.A. Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the

University of Oxford. Third Edition. 1879.

14-11-2018

● kimkat0001 Yr Hafan www.kimkat.org

● ● kimkat2001k

Y Fynedfa Gymraeg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwefan/gwefan_arweinlen_2001k.htm

● ● ● kimkat0960k Mynegai ir holl destunau yn y wefan hon www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_llyfrgell/testunau_i_gyd_cyfeirddalen_4001k.htm

● ● ● ● kimkat0960k

Mynegai ir testunau Cymraeg yn y wefan hon www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/sion_prys_mynegai_0960k.htm

● ● ● ● ● kimkat2121k The Philology of the English Tongue /

Astudiaeith Gymharol or Iaith Saesneg 1879 - Y Gyfeirddalen

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/testun-246_philology-english-tongue_earle_1879_y-gyfeirddalen_2121k.htm

● ● ● ● ● ● kimkat2125k

y tudalen hwn

|

|

|

Gwefan

Cymru-Catalonia |

|

.

...

llythrennau duon = testun wedi ei gywiro

llythrennau gwyrddion = testun heb ei gywiro

.....

|

|

|

|

v |

4jO VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

476. This is, however, but a feeble example of the pronominal use of the word

man, a use which it has been our singular fortune to lose after having

possessed it in its fulness. In place of it, we resort to a variety of shifts

for what may justly be called a pronoun of pronouns, that is to say, a pronoun

which is neither / nor we nor you nor they, but which may stand for either or

all of these or any vague commixture of two or three of them. Sometimes we

say 'you' not meaning, nor being taken to mean you at all, but to express a

corporate personality which quite eludes personal application. It is always

pleasant to be forced to do what you wish to do, but what, until pressed, you

dare not attempt. Dean Hook, Archbishop*. vol. iii. ch. 4. This you is

often convenient to the poet as a neutral medium of address, applicable

either to one particular person, or to all the world: Yet this, perchance,

you '11 not dispute, That true Wit has in Truth its root, Surprise its

flower, Delight its fruit. Sometimes, again, it is we, and at other times it

is they which represents this much-desired but long-lost or notyet-invented '

representative ' pronoun. We render the French ' on dit' by they say. 477.

Besides the resort to pronouns of a particular person in order to achieve the

effect of a pronoun impersonal, we have also some substantives which have

been pronominalised to this effect, as person, people, body, folk. people.

Bothwell was not with her at Seton. As to her shooting at the butts when

there, this story, like most of the rest, is mere gossip. People do not shoot

at the butts in a Scotch February. Quarterly Review, vol. 12S. p. 511. |

|

|

|

|

|

1. SUBSTANTIVAL. INDEFINITES.

45 1 People are always cowards when they are doing wrong. M. Manley, W)ien

I was a Boy (William Macintosh), p. 24. body. The foolish body hath said in

his heart, There is no God. Psalm liii. I, elder version. And from this we

get the composite pronouns somebody, nobody, everybody, and a-body, as little

John Stirling, when he saw the new-born calf Wull't eat a-body? Thomas

Carlyle, Life, ch. ii. In like manner, but less fixed in habit, some people,

and also some folk, as in the well known refrain Some folk do, some folk do!

478. One. The first numeral has an intimate natural affinity with the

pronominal principle, and this is widely acknowledged in the languages by

pronominal uses which are very well known. Some of our pronominal uses of one

are easily paralleled in other languages, the one and the other = Tun et T

autre; one another = Tun l'autre. But there is an English use which is far

from common, even if it is not absolutely unique; namely, when it is employed

as a veiled Ego, thus: 'One may be excused for doubting whether such a policy

as this can have its root in a desire for the public welfare '; or, ' One

never knows what this sort of thing may lead to.' It would be impossible to

put in these places Vim or ein or unus or eh. The one of which we speak is

quite distinct from those cases in which it is little removed from the

numeral, as 1 One thinks this, and one thinks that.' In this case one is

fully toned, but not so in the case referred to, as when a person who is

pressed to buy stands on the defensive with, 'One can't buy everything, you

know'; here the one is Gg 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

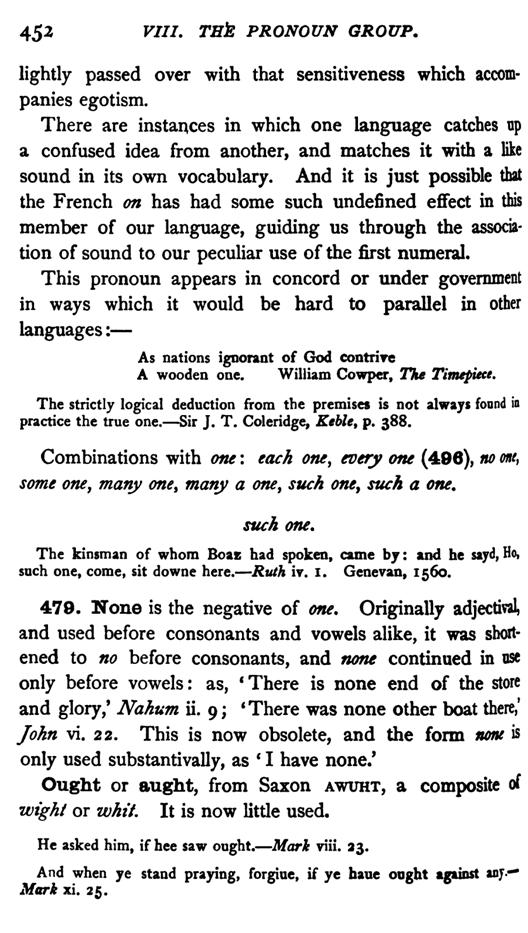

4$2 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

lightly passed over with that sensitiveness which accompanies egotism. There

are instances in which one language catches up a confused idea from another,

and matches it with a like sound in its own vocabulary. And it is just

possible that the French on has had some such undefined effect in this member

of our language, guiding us through the association of sound to our peculiar

use of the first numeral. This pronoun appears in concord or under government

in ways which it would be hard to parallel in other languages: As nations

ignorant of God contrive A wooden one. William Cowper, The Timepiece. The

strictly logical deduction from the premises is not always found in practice

the true one. Sir J. T. Coleridge, Keble, p. 388. Combinations with one:

each one, every one (496), no one, some one, many one, many a one, such one,

such a one. such one. The kinsman of whom Boaz had spoken, came by: and he

sayd, Ho, such one, come, sit downe here. Ruth iv. 1. Genevan, 1560. 479.

None is the negative of one. Originally adjectival, and used before

consonants and vowels alike, it was shortened to no before consonants, and

none continued in use only before vowels: as, ' There is none end of the

store and glory,' Nahum ii. 9; 'There was none other boat there,' John vi.

22. This is now obsolete, and the form none is only used substantially, as '

I have none.' Ought or aught, from Saxon awuht, a composite of wight or whit.

It is now little used. He asked him, if hee saw ought. Mark viii. 23. And

when ye stand praying, forgiue, if ye haue ought against any. Murk xi. 25. |

|

|

|

|

|

2. ADJECTIVAL. POSSESSIVES.

453 Nought or naught is composed of tie and ought or aught. Few. Once common

to the whole Gothic family, this pronoun survives only in the English and

Scandinavian. Anglo-Saxon feawa, Mceso-Gothic fawai, Danish faa. A variety of

other pronouns belong to this set, which we have only space just to hint at.

Such are thing, something, everything, nothing; wight, whit, deal. We have

thus reached the natural termination of this section. Having started from the

pronouns which were most nearly associated with definite substantival ideas,

we have reached those whose characteristic it is (as their name conveys) to

be indefinite, to shun fixed associations, and thus to be ever ready for a

latitude of application as wide as the widest imaginable sweep of the mental

horizon. II. Adjectival Pronouns. 480. This section will run parallel to the

former, as each group of Pronouns has its substantives and its adjectives.

Yet it may be observed that the more subtle quality of pronouns, as compared

with nouns, is the cause of a more ready transition from the substantival to

the adjectival function, and reversely. 481. The Possessive Pronouns. These

were a genitival shoot from the personal pronouns which became, some more some

less, adjectival: those which became most so were the possessives of the

first and second persons. These have, in the earlier stage of the language,

had a complete adjectival development, and full means of concord |

|

|

|

|

|

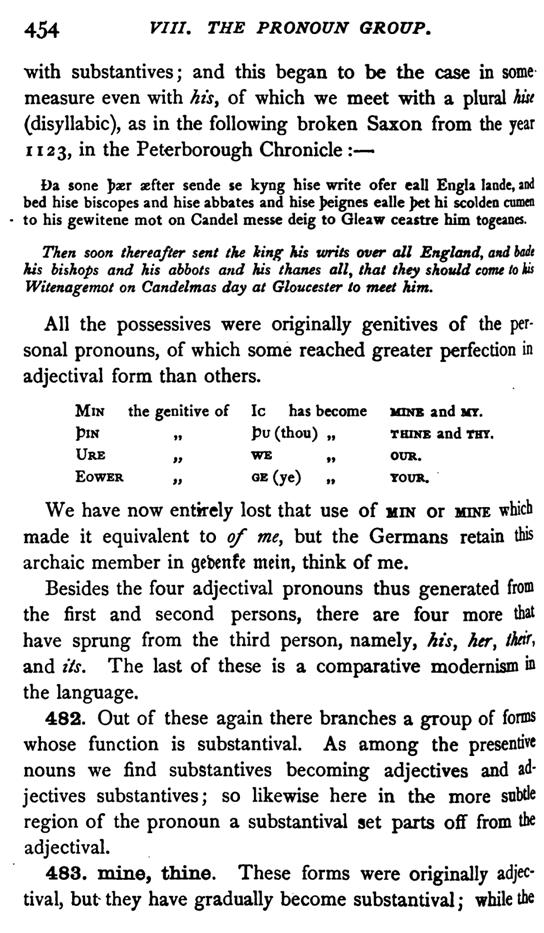

454 VIU - THE PRONOUN GROUP. with

substantives; and this began to be the case in some measure even with his, of

which we meet with a plural hise (disyllabic), as in the following broken

Saxon from the year 1 123, in the Peterborough Chronicle: Da sone J>aer

aefter sende se kyng hise write ofer eall Engla lande, and bed hise biscopes

and hise abbates and hise })eignes ealle pet hi scolden cumen to his gewitene

mot on Candel messe deig to Gleaw ceastre him togeanes. Then sooyi thereafter

sent the king his writs over all England, and bade his bishops and his abbots

and his thanes all, that they sho?dd come to his Witenagemot on Catidelmas

day at Gloucester to meet him. All the possessives were originally genitives

of the personal pronouns, of which some reached greater perfection in adjectival

form than others. |

|

|

|

|

|

2. ADJECTIVAL. POSSESSIVES.

455 reduced my, thy, occupy the old domain. When the N was first dropped, it

was because the following word began with a consonant, and then the

difference between mine, thine, and my, thy, was like that between an and a t

or the original distinction between none and no. In Chaucer's verse we find

the N-form unremoved before consonants, as Myn purchas is the effect of al

myn rente. Canterbury Tales, 7033. But in his prose he was more familiar, and

we find my, thy, before consonants in the opening sentences of the Treatise "ii

the Astrolabe: Litell Lowys my sone, I haue perceiued well by certeyne

euidences thine abilite to lerne sciencez touchinge noumbres &

proporciouns; & as wel consiJere I thy bisi preyere in special to lerne

the tretis of the astrelabie. But considere wel, that I ne vsurpe nat to haue

fownde this werk of my labour or of myn engin. I nam but a lewd compilatour

of the labour of olde Astrologiens, and haue hit translated in myn englissh

only for thi doctrine; and with this swerd shal I slen envie. Ed. W. W.

Skeat, pp. I, 2. And so it continues in the Bible of 161 1: Thou didst ride

vpon thine horses, and thy charets of saluation. Habakkult iii. 8. 484.

Ours, yours, hers, theirs. In these cases the substantival possessive is made

by the cumulative addition of the s genitival to its previously genitival

termination. Against this s the rustic tradition maintains its old rival n;

and hence a uniform series of substantival possessives, mine, thine, hisn,

hern, oum, yourn, theirn, current among the purest English folk. Theirs. The

distinction between adjectival their and substantival theirs is well

exhibited in the following lines: Leave kingly backs to cope with kingly

cares; They have their weight to carry, subjects theirs. William Cowper,

Table Talk. |

|

|

|

|

|

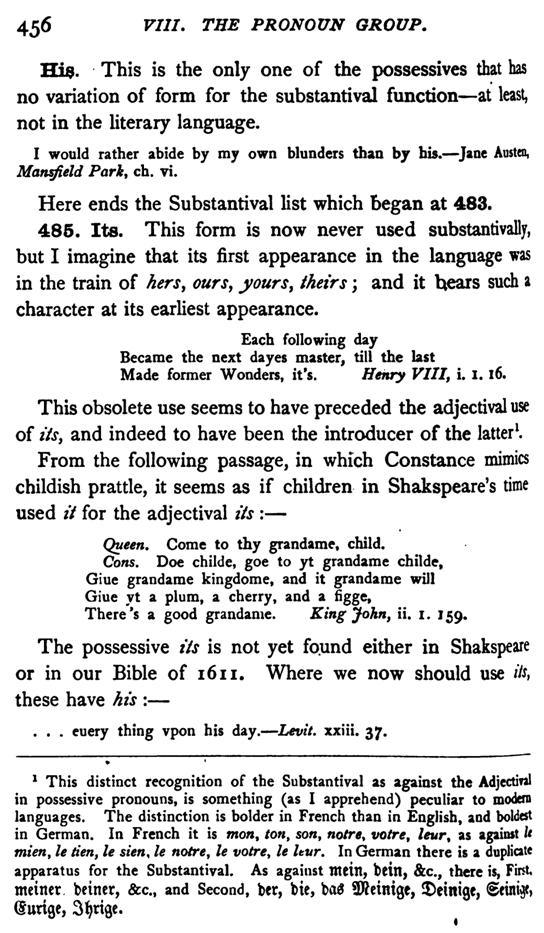

45<5 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

His. This is the only one of the possessives that has no variation of form

for the substantival function at least, not in the literary language. I

would rather abide by my own blunders than by his. Jane Austen, Mansfield Park,

ch. vi. Here ends the Substantival list which began at 483. 485. Its. This

form is now never used substantivallv, but I imagine that its first

appearance in the language was in the train of hers, ours, yours, theirs; and

it bears such a character at its earliest appearance. Each following day

Became the next dayes master, till the last Made former Wonders, it's. Henry

VIII, i. I. 1 6. This obsolete use seems to have preceded the adjectival use

of its, and indeed to have been the introducer of the latter 1 . From the

following passage, in which Constance mimics' childish prattle, it seems as

if children in Shakspeare's time used it for the adjectival its: Queen.

Come to thy grandame, child. Cons. Doe childe, goe to yt grandame childe,

Giue grandame kingdome, and it grandame will Giue yt a plum, a cherry, and a

figge, There's a good grandame. King John, ii. I. 159. The possessive its is

not yet found either in Shakspeare or in our Bible of 1611. Where we now

should use its, these have his: . . . euery thing vpon his day. Levit.

xxiii. 37. 1 This distinct recognition of the Substantival as against the

Adjectival in possessive pronouns, is something (as I apprehend) peculiar to

modern languages. The distinction is bolder in French than in English, and boldest

in German. In French it is mon, ton, son, notre, votre, leur, as against le

mien, le den, le sien. le notre, le votre, le Itur. In German there is a

duplicate apparatus for the Substantival. As against Weill, bctll, &c,

there is, Fir>t. meitter bcincr, &c, and Second, ber, bie, ba3

Sftciuicje, ©cinigc, @einige, (Sutige, 3brtge. |

|

|

|

|

|

457 |

|

|

|

|

|

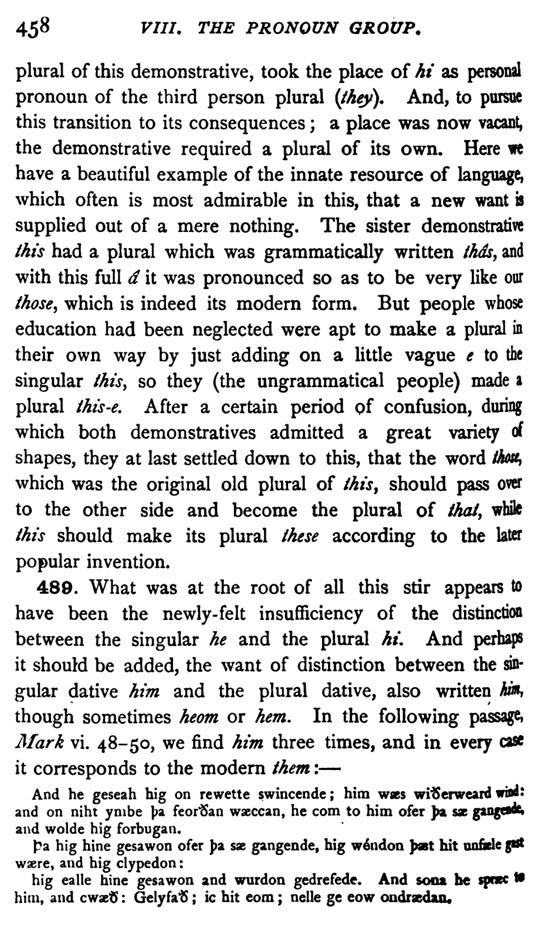

45^ VI H- THE PRONOUN GROUP.

plural of this demonstrative, took the place of hi as personal pronoun of the

third person plural (they). And, to pursue this transition to its

consequences; a place was now vacant, the demonstrative required a plural of

its own. Here we have a beautiful example of the innate resource of language,

which often is most admirable in this, that a new want is supplied out of a

mere nothing. The sister demonstrative this had a plural which was

grammatically written thds, and with this full a it was pronounced so as to

be very like our those, which is indeed its modern form. But people whose

education had been neglected were apt to make a plural in their own way by

just adding on a little vague e to the singular this, so they (the

ungrammatical people) made a plural this-e. After a certain period of

confusion, during which both demonstratives admitted a great variety of

shapes, they at last settled down to this, that the word those, which was the

original old plural of this, should pass over to the other side and become

the plural of that, while this should make its plural these according to the

later popular invention. 489. What was at the root of all this stir appears

to have been the newly-felt insufficiency of the distinction between the

singular he and the plural hi. And perhaps it should be added, the want of

distinction between the singular dative him and the plural dative, also

written kt'm, though sometimes heom or hem. In the following passage, Mark

vi. 48-50, we find him three times, and in every case it corresponds to the

modern them: And he geseah hig on rewette swincende; him waes wiSerweard

wind: and on niht ynibe pa feorSan waeccan, he com to him ofer J)a see

gangende, and wolde hig forbugan. pa hig hine gesawon ofer )>a sae

gangende, hig wendon J?aet hit unfaele gast w;ere, and hig clyptdon: hig

ealle hine gesawon and wurdon gedrefede. And sona he spra?c to him, and

cwie'tf: Gelyfaft; ic hit eom; nelle ge eow ondrsedan. |

|

|

|

|

|

2. ADJECTIVAL. DEFINITE

ARTICLE. 459 So that the English language, about the time of its national

restitution, gradually substituted they, their, them, in the place of the

elder hi, heora, him. This change was not quite established till far on in

the fifteenth century. In Chaucer we have still the elder forms, hi, hir,

kem, in free use, or at least the two latter. For the nominative he generally

uses they: Vp on the wardeyn bisily they crye, To yeue hem leue but a litel

stounde, To go to Mille and seen hir corn ygrounle: And hardily they derste

leye hir nekke, The Millere shold noght stelen hem half a pekke Of corn by

sleighte. ne by force hem reue: And atte laste the wardeyn yaf hem leue. The

Reeves Tale, 4006. It may not be amiss to add that when in provincial

Engglish we meet with 'em in place of them, it must be regarded as an elided

form not of them, but of hem. 490. These two pronouns have held a great place

in our language. We can hardly omit to notice what may be called their

rhetorical use. This has a rhetorical use expressive of contempt. It was by

means of this pronoun that Home Tooke expressed his contempt for the

philology of Harris's Hermes: There will be no end of such fantastical

writers as this Mr. Harris, who takes fustian for philosophy. Diversions of

Parley, Part II. ch. vi. That, on the other hand, is a great symbol of admiration:

The face of justice is like the face of the god Janus. It is like the face

of those lions, the work of Landseer, which keep watch and ward around the

record of our country's greatness. She presents one tranquil and majestic

countenance towards every point of the compass and every quarter of the

globe. That rare, that noble, that imperial virtue has this above all other

qualities, that she is no respecter of persons, and she will not take

advantage of a favourable moment to oppress the wealthy for the sake of

flattering the poor, any more than »he will condescend to oppress the poor

for the sake of pampering the luxuries of the rich. House of Commons, March

11, 1870. |

|

|

|

|

|

460 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

Both of these uses are to be paralleled in Greek and Latin, as the student of

those languages should ascertain for himself, if he is not already familiar

with the feature. 491. But a more peculiar interest attaches to this pronoun

from the circumstance that out of it has been carved the definite article.

The word the is generalized from the more prevalent cases of thcet, and

perhaps the French le has exercised some influence in the way of shaping the.

And not unfrequently we experience in the course of reading, especially in

poetry, a certain force in the definite article, which we could not better

convey in words than by saying it reminds us of its parentage, and calls the

demonstrative to mind. It is one of those fugitive sensations that will not

always come when they are called for; but perhaps the reader may catch what

is meant if the following line from the Christian Year is offered in

illustration: The Man seems following still the funeral of the Boy. The

same thing may however be shown in a manner more agreeable to science. We

find cases in which the same text is variously rendered according as the

interpreters have seen a demonstrative or a definite article in the original:

Ezehel ix. 19. 1535. 1611. That stony herte wil I take out I wil take the

stonie herte out of youre body, & geue you a fleshy of their flesh, and

will giue them an herte. heart of flesh. There is a case, and that rather a

frequent one, in which the is not a definite article at all, but either a

demonstrative or a relative. It is the instrumental case thy of the Saxon declension

above given, and answers to the Latin quo. . . eo before comparatives, just

as thcet that in Saxon was equivalent to the Latin id quod. |

|

|

|

|

|

2. ADJECTIVAL. INTERROGATIVE,

ETC. 46 1 The more luxury increases, the more urgent seems the necessity for

thus securing a luxurious provision. John Boyd-Kinnear, Woman's Work, P-

353 492.

Yond, yon, yonder. Saxon geoxd, German jener: Mene. See you yond Coin a'th

Capitol, yond corner stone? W. Shakspeare, Coriolanus, v. 4. I. But looke,

the Morne in Russet mantle clad, Walkes o're the dew of yon high Easterne

Hill. Hamlet, i. 1. 167. Caesar saide to me, Dar'st thou Cassius now Leape in

with me into this angry Flood, And swim to yonder Point? Julius Ccesar, i. 2.

104, Near yonder copse, where once the garden smil'd. Oliver Goldsmith, The

Deserted Village. Saxon, from yonder mountain high, I mark'd thee send

delighted eye. Walter Scott, Lady of the Lake, v. 7. |

|

|

|

|

|

46 Z VIII, THE PRONOUN GROUP.

the native growth as cuttings differ from seedlings. Only a reduced number

gets well and permanently rooted. We proceed to notice an instance of this.

The relative which, as a personal relative, is no longer used, and it is a

well-known peculiarity of the English of our Bible, that it is so common

there. Instances of this use are indeed numerous beyond the pages of that

version. The following is from a brass in Hutton Church, near

Westonsuper-Mare: Pray for y e soules of Thomas Payne Squier &

Elizabeth hyis wiffe which departed y e xv th day of August y e yere of o r

lord god m.ccccc.xxviij. In the following passage Pope put Whom as a

correction in the place of Which: Welcome sir Diomed, here is the Lady

Which for Anterior we deliuer you. Shakspeare, Troylus and Cressida, iv. 4.

109. ' Another French -trained faculty was once enjoyed by which, but is now

obsolete. This was the admirative or exclamative power, like the French quel,

quelle! In the following instances we should now put what instead oiwhich:

And which eyen my lady had, Debonaire, good, glad, and sad. Geoffrey Chaucer,

Blauncke, 859. But which a visage had she thereto. Id. 895. Whether = which

of two? was in Saxon an adjectival pronoun, declined in the three genders;

whereas now it has not only lost its concordal faculty, but has almost

dropped out of knowledge as a pronoun altogether (537). In the seventeenth

century it was still used. Strafford, writing to Laud of his opening speech,

says: Well spoken it is, good or bad. I cannot tell whether; but whatever

it was, I spake it not betwixt my teeth, but so loud and heartily that I protest

unto you I was faint withal at the time, and the worse for it two or three

days after. J. B. Mozley, Essays, 'Lord Strafford,' p. 27. |

|

|

|

|

|

2. ADJECTIVAL. INDEFINITES. 463

Indefinite Pronouns. 494. Many keeps the place of the Saxon masig, except in

so far as it has received additions from Danish in the formulas many one,

many a one, many a: To many a man and many a maid Dancing in the chequered

shade. John Milton, f Allegro. Same. This word is not found (as a pronoun) in

AngloSaxon literature, and the question arises whence it came° to be so

familiar in English. Jacob Grimm thinks it was acquired through the Norsk

language, in which same is a prevalent pronoun. The Saxon word in its place

was ik wh,ch is so well known to us through Scottish literature As however

there are traces of its having existed at an earlier stage of Saxon, it is

possible that it had never died out, but that having been superseded by ilk

in the written language it had only fallen into temporary obscuritv. Many

genuinely nat.ve elements are found in modern English which are unknown in

Saxon literature, and it is only reasonable to conclude that the vocabulary

of the Saxon literature imperfectly represented the word-store of the nation

495. Own. Saxon agen, German eigen. This is an ancient participle of a Saxon

verb agax, to possess None no. None is from ne and one, Saxon xak. The

history of the shortened form of no is just the same as that of my, thy-. a ,

first it was a C0ncessj0n to the jn . tial cQn _ sonant of the following word,

thus in the Bible of ,6,i there was none other boat there,' and ' no man

knoweth whence. At this stage the relation of none, no, was like that of an,

a; but the former pair did not rest in that conditton as the latter did. The

form no has now occupied all |

|

|

|

|

|

464 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

situations where it is adjectival; and none is kept for the substantival

function: as, 'Have you no other?' 'I have |

|

|

|

|

|

2. ADJECTIVAL. INDEFINITES. 46

5 The very presence of a true-hearted friend yields often ease to our grief.

R. Sibbs, So?tles Conflict, 14; ed. 165S, p. 199. In the very centre or

focus of the great curve of volcanoes is placed the large island of Borneo.

Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, ch. i. A choice illustration

may be had from a letter written in 1666 by the wife of the English

ambassador at Constantinople to her daughter Poll in England, which Poll has

been adopted by a rich relative, and is inclining to vanity l: Whereas if

it were not a piece of pride to have y e name of keeping y r niaide, she y*

waits on y r good grandmother might easily doe as formerly vou know she hath

done, all y e business you have for a maide, unless as you grow old r you

grow a veryer Foole, which God forbid! Certain is an adjective which has been

presentive not long ago, but it is now completely pronominalised: At

Clondilever, a farmer was returning from his usual attendance at the Roman

Catholic Chapel on Sunday, when he was stopped by five men with revolvers,

who warned him that if he interfered any further with a certain person as to

possession of a certain field, &c. April 30, 1870. 498. Our last

adjectival pronouns shall be one and its derivative only. The only prime

minister mentioned in h: story whom his contemporaries reverenced as a saint.

William Robertson, Charles V, Bk. I. a.d. 15 1 7. One has already been

largely spoken of in the former section, where it was seen to occupy an

important place. But its substantival function is after all less important in

the development of our language than its adjectival habit; because out of

this has grown that member which is the most distinctive perhaps that can be

fixed upon as the mark of a modern language. The definite article is found in

some of the ancient languages, as in Hebrew and Greek, but none 1 Of this

vain Poll, the great grand-daughter was Jane Austen, and it is in the Memoir

of the latter, by the Rev. J. E. Austen-Leigh (Bentley, 1 8 70), that this

admirable letter has been published. Hh |

|

|

|

|

|

466 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP. of

them had produced an Indefinite Article. The general remark has already been

made in an earlier chapter, that it is in the symbolic element we must seek

the distinctive character of the modern as opposed to the ancient languages.

And we may appeal to the indefinite article as the most recent and most

expressive feature of this modern characteristic. In the Greek of the New

Testament there are certain indications (known to scholars) of something like

an indefinite article. In its adjectival use this pronoun is generally set in

antithesis to another) as, Yf one Sathan cast out another. Matt. xii. tr.

Coverdale, 1535. Out of this has been produced the indefinite article. It has

not sprung directly from the numeral one, but from that word after it has

passed through the refining discipline of a pronominal usage. The old

spelling of the numeral was an; and this ancient form is preserved in the

article an Or a. This gives us occasion to remark that old forms are often

preserved in the more elevated functions, while the original and inferior

function has admitted changes. 499. Having thus indicated the sources of our

two articles, let us observe that they still carry about them the traces of

their extraction. The magnifying quality of the demonstrative that has been

noticed above. Its descendant the definite article retains something of this

ancestral quality. We all know how the ceremonious The adds grandeur to a

name, and how all titles of office and honour are jealously retentive of this

prefix. On the other hand, the indefinite article, which is descended from

the littlest of the numerals, exercises a diminishing effect, as in the

following: |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (l) FLAT. 46 J

This little life-boat of an earth, with its noisy crew of a mankind, and all

their troubled history, will one day have vanished. Thomas Carlyle, Essays;

Death of Goethe. These minute vocables are the real ' winged words ' of human

speech; or, to speak with more exactness, they are the wings of other words,

by means of which smoothness and agility is imparted to their motion. It is

in the articles that the symbolic element of language reaches one of its most

advanced points of development; and it is not by means of these alone, but by

means of that whole system of words of which these are eminent types, that

the modern languages when compared with the ancient are found to excel in

alacrity and sprightliness. |

|

|

|

|

|

468 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP. The

examples which follow may therefore be considered as a continuation of the

corresponding group in the section of nounal adverbs, and differing from them

only in the degree of sublimation. All. A pronominal adverb of great delicacy

and power: Through the veluet leaues the winde, All vnseene, can passage

finde. Loues Labour's lost, iv. 3. . . . feeling that my praise of Harvey has

been all too feeble. George Rolleston, The Harveian Oration, 1873, p. 90.

Yond, yon, yonder. 492. Pro. The fringed Curtaines of thine eye aduance, And

say what thou see'st yond. W. Shakspeare, The Tempest, i. 2. 408. Adam.

Yonder comes my Master, your brother. As You Like It, i. I. 28. 501. Up. This

is clearly a presentive word so long as the original idea of elevation is

preserved. But it passes off into a more refined use, a more purely mental

service, and then we call it no longer a noun but a pronoun. The instance of

breaking-up is an interesting one. It is one of those in which the flat

adverb has attached itself very closely to the verb, and has with the verb

attained a peculiar appropriation of meaning. This expression now is apt to

suggest the holidays of a school-boy, but in the sixteenth century it was the

proper expression for burglary: If a thiefe bee found breaking vp. Exodus

xxii. 2. Suffered his house to be broken vp. Matthew xxiv. 43. If he beget

a sonne that is a breaker vp of a house. Ezekiel xviii. 10 (margin). Mr.

Froude quotes a letter of the reign of Queen Elizabeth j in which a burglary

is confessed in these terms:. |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (i) FLAT. 469

With other companions who were in straits as well as myself, I was forced to

give the onset and break up a house in Warwickshire, not. far from Wakefield.

History, vol. xi. p. 28. An old ship is sold ' to be broken up,' and akin

to this we find the substantive a break-up: The death of a king in those

days came near to a break-up of all civil society. E. A. Freeman, Norman

Conquest, ch. xxi. There is a rich variety of expressions in which up figures

in the character which belongs here; e. g. to be ' knocked up/ ' done up,' '

patched up,' to be ' up to a thing,' ' up with a person,' ' keeping it up

late,' ' open up ' 503. The verb to come up is equivalent to coming into

notice, or even into being; and in the following quotation it translates

eyevero '. As for wisedome what she is, and how she came vp, I will tell

you. Wisedome of Solomon, vi. 22. At length it becomes a mere symbol of

emphasis. In Rom. vi. 13, 'yield yourselves unto God,' it is proposed by

Bishop Ellicott to restore a certain lost emphasis by the correction, 'yield

yourselves up to God.' Still. In the next examples the reader may notice that

'still run' and 'still to move' would be pure stultifications if the word

still were taken in its original and presentive signification of motionless

stillness. This affords a sort of measure of the symbolic change that has

passed over the word. Having past from mj hand under a broken and imperfect

copy, by frequent transcription it still run {sic) forward into corruption.

Thomas Browne, Religio Medici, Preface. They are left enough to live on, but

not enough to enable them still to move in the society in which they have

been brought up. John BoydKinnear. Woman's Work, p. 353. 502. Rather. This

word may serve as an illustration of the grounds on which we assign these

words to the pro |

|

|

|

|

|

47° VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

nominal category; In an interesting letter from Sir Hugh Luttrell, in the

year 1420, we have this word in its presentive sense. He is in France, and he

is displeased that certain orders of his have not been carried out, and he

hints that if his commands are not fulfilled, he is alive, and ' schalle come

home, and that rather than some men wolde,' that is to say, he shall be at

home earlier than would be agreeable to some people. Rather is the

comparative of an obsolete adjective rathe, which signified ' early.' It is

found once in Milton, Lycidas, 142: Bring the rathe Primrose that forsaken

dies, The tufted Crow-toe, and pale Gessamine. Now compare the way in which

we habitually employ this word, and a plainer example could hardly be found

of the distinction between the nature of the noun and that of the pronoun.

The word is so common that we can hardly read a paragraph in any daily or

weekly article without coming across it, and probably more than once. He

fails to be truly pathetic because we do not see the agony wrung out of a

strong man by the inevitable wrongs and sorrows of the world, but the easy

yielding of a nature that rather likes a little gentle weeping. Mr. Pickwick,

with his love of mankind stimulated with a little milk-punch, is not the most

elevated type of philanthropy, though it is one which is rather prevalent at

the present day. In these respects Mr. Dickens's influence tended rather

towards a softening of the moral fibre than towards strengthening it. July

16, 1870. Too. This is an Ablaut-variety of the preposition to: Spake I not

too truly, O my knights? Was I too dark a prophet when I said To those who

went upon the Holy Quest, That most of them would follow wandering fires,

Lost in the quagmire? Alfred Tennyson, The Holy Grail. 503. So. This famous pronominal

factor, which has already been spoken of in both the previous sections, must

come in here likewise: ■ |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (i) FLAT. 471

And he was competent whose purse was so. William Cowper, The Time-Piece. A

declaration so bold and haughty silenced them and astonished their

associates. The presentive idea to which this so points back may be found by

reference to Robertson's Charles the Fifth, Bk. I. anno 15 16, and the

abruptness of the clause as it stands gives a measure of the pronominal

nature of the adverb so. further. Or dwells within our hidden soul Some germ

of high prophetic power, That further can the page unveil, And open up the

future hour. G. J. Cornish, Come to the Woods, and Other Poems, lxxiii. Jump.

In goodnes therefore there is a latitude or extent, whereby it commeth to

passe that euen of good actions some are better then other some; whereas

otherwise one man could not excell another, but all should be either

absolutely good, as hitting jumpe that indiuisible point or center wherein

goodnesse consisteth; or else missing it they should be excluded out of the

number of wel-doers. Richard Hooker, Of the Laws, &c. I. viii. 8. And

bring him iumpe, when he may Cassio finde. Othello, ii. 3. 369. For this

adverb the editors substitute /mj/. In the following quotation from the First

Folio, the old Quartos have jump: Mar. Thus twice before, and iust at this

dead houre, With Martiall stalke, hath he gone by our Watch. Hamlet, i. 1.

65. just. How much of enjoyment life shows us, just one hair's breadth beyond

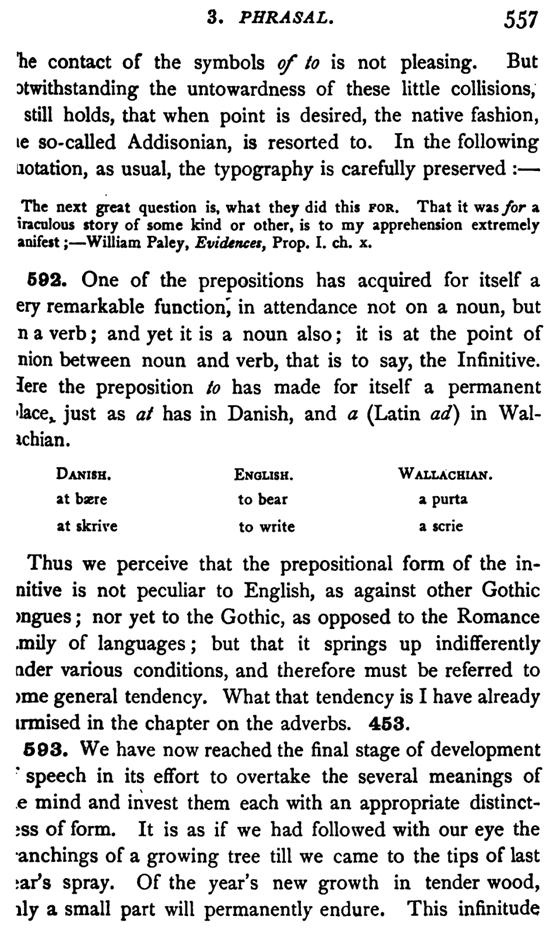

our power to grasp. The Bramleighs, ch. xxxi. solid. 4 You don't mean that?

' I do, solid! ' (Leicestershire.) |

|

|

|

|

|

47 2 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

some, much. Suppose a man's here for twelve months. Do you mean to say he

never comes out at that little iron door?-He may walk some, perhaps .-not

much. Charles Dickens, in Foster's Life, ch. xxi. It is not necessary to the

Flat Adverb that it should consist of a single word, though it generally does

so. Such adverbs as that time, no thynge, the right way, the wrong way, the

ivhile must be placed here. thai time, no thynge. Ireland bat tyme was bygged

no pynge Wvp hous ne toun, ne man wonynge. R. Brunne's Chronicle (Lambeth

MS.). Translation.-/^^ at that time was not-at-all built with house nor town,

nor man resident. He said he loved and was beloved no thing. Canterbury

Tales, 11,258. Next we have the adverb nothing in one word, as 'nothing

loth,' ' nothing doubting.' Here we must, at least provisionally, and without

speculation on their origin, put the adverbs of affirmation, yea and>w,

Saxon ge and gese. The following is from Dr. Bosworth's Parallel Gospels,

Mattheiv v. 37: Gothic, 360. Wycliffe, 1389. Tyndale, 1526. l6ll. Sivaith

than But be 5 oure But your com- But let your com Siyaith tnan ', ea . mU nicacion

shalbe municationbee Yea, ^"e ZtZ ' Ye, ye; Nay, nay. yea; Nay, nay.

Matthew xi. 9: Tr . ... . 5. T seie to Ye.Isayevnto Yea, I say vnto Yai,

qiba izvis. 3?> l seie IU ' ' you. y° u - y0U * 504. Next we come upon a

member which is inconsiderable in its bulk, unimposing in its appearance, and

which is inconspicuous by the very continuousness of its presence; |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (l) FLAT. 473

but yet one which covers with its influence half the realm of language, which

involves one of the most curious of problems, and which raises one of the

most important questions in the whole domain of philological speculation: I

mean the apparatus of Negation. It may be out of our reach to attain to the

primitive history of the negative particle; but if we are to judge of its

source by the track upon which it is found, if origin is to be judged of by

kindred, if the unknown is to be surmised by that which is known, it is in

this portion of the fabric of speech namely in the flat pronounadverbs

that we must assign its birthplace to the negative particle. The negative

particle in our language is simply the consonant n. In Saxon it existed as a

word ne, but we have lost that word, and it is now to us a letter only, which

enters into many words, as into no, not, nought, none, never. In French,

however, this particle is still extant as a separate word; as ' Je ne vois

pas/ 505. The following parallel quotations exhibit this particle both in its

simple state, and also in combinations, some familiar, some strange to us:

Anglo-Saxon, 995. Wycliffe, 1389. Ne geseah naefre nan man God, No man euere

sy3 God, no but buton se an-cenneda sunu hit cySde, the oon bigetun sone,

that is in the se is on his faeder bearme. And ftaet bosum of the fadir, he

hath told out. is Johannes gewitnes, Sa fta Judeas And this is the witnessing

of John, sendon hyra sacerdas and hyra dia- whanne lewis senten fro Jerusalem

conas fram Jerusalem to him, ftaet hi prestis and dekenys to hym, that

acsodon hyne and "8us cwaedon, Hwaet thai schulden axe him, Who art

thou? eart iSii? And he cydde, and ne And he knowlechide, and denyede wid">uc,

and Sus cwaep, Ne eom ic not, and he knowlechide, For I am na Crist. And hig

acsodon hine and not Crist. And thei axiden him, Sus cwaedon, Eart ou Elias?

And What therfore? art thou Elye? he cwaep Xe eom ic hit. Da cwaedon And he

seide, 1 am not. Art thou hi, Eart ftu witega? And he and- a prophete? And he

answeride, wyrde and cwaep, Nic. Nay. St. John, i. 18-21, Bosworth's Gospels.

|

|

|

|

|

|

474 v 111 ' THE PR° N0UN group.

506. In Anglo-Saxon the particle ne was used not only for the simple

negative, as in the above quotation, but likewise as our nor: and both of

these uses continued to the fourteenth century. Thus, in the Vision of Piers

the Plowman, Prologue 174: Alle bis route of ratones ■ to bis reson thei assented Ac bo be belle was ybou 5 t ■ and on be be^e hanged, Pere newas ratonn in alle be ronte ■ for alle be rewme of Fraunce, Pat dorst haue ybounden be belle ■ aboute be cams nekke Ne hangen it aboute be cattes hals ■ al Engelonde to Wynne. 507. In Chaucer we find the ne in both senses. The following

examples are all from the Prologue. ne = not. He neuere yit no vilonye ne

saide. (1. 70.) That no drop ne fell upon hir breste. (1. 13 *) So that the

wolf ne made it not miscarie. (L 5 T 3-) ne = nor. Ne wete hir fyngres in hir

sauce depe. (1. 129.) Ne that a monk whan he is recheles. (1. 179.) Ne was so

worldly for to haue office. (I. 292.) Ne of his speche dangerous ne digne.

(1. 5 1?-) Ne maked him a spiced conscience. (1. 526.) ne in both senses. But

he ne lefte nought for rayn ne thondre. (1. 49 2 -) When ne as a simple

negative had been superseded by not, it still continued in the sense of nor,

and thus we find it in Spenser, The Faery Queene, i. 1. 28: Then mounted he

upon his Steede againe, And with the Lady backward sought to wend. That path

he kept which beaten was most plaine, Ne ever would to any byway bend, But

still did follow one unto the end The which at last out of the wood them

brought. So forward on his way (with God to frend) He passed forth, and new

adventure sought: Long way he travelled before he heard ot ought. |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (i) FLAT. 475

508. Jacob Grimm would distinguish the former ne from the latter, writing the

simple negative as tie, and the equivalent of ' nor' as ne. This he educes

from comparison of the collateral forms, such as nth in Gothic for ' nor.' It

is some confirmation of Grimm's view, that the?ie to which he gives the long

vowel, outlived the other, and that it took so much longer time to become

merged in newer forms. This is in itself an argument for the probability of

its having been a weightier syllable. 509. Another form of this negative was

the prefix un-, which has lived through the Saxon and English period without

much change. 606 a. It has always been a peculiarly expressive formula, and

often strikingly poetical. ungrene. Folde waes J)a gyt Graes ungrene, garsecg

fceahte. Caedmon, Il6. The field was yet-whiles With grass not green; ocean

covered all. Indeed, it is a very great factor in Anglosaxon. It stands in

places where we have lost and might gladly recover its use, and where at

present we have no better substitute than the clumsy device of prefixing a

Latin non. In the Laws of I?te, we have the distinction between landowners

and non-landowners expressed by land dgende and un land dgende. In Chaucer

and in the Ballads we meet with ' unset steven' for chance- meeting, meeting

without appointment. Gawin Douglas, in The Palace of Honour, written in 1501,

ranks Dunbar among the illustrious poets, and adds that he is yet undead: '

Dunbar yit undeid.' unborrowed. Wi'.h orient hues, unborrowed of the sun.

Gray. |

|

|

|

|

|

47 6 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

510. This N-particle is not limited to the Gothic family. It appears in Latin

ne, non, and in- the negative prefix so well known in our borrowed Latin words,

as indelible, intolerable, invincible, inextinguishable. In Greek it appears

in the prefix an-, as in our borrowed Greek words, anecdote untold before,

anodyne which cancels pain, anomaly unevenness, anonymous unnamed. There is

something strange and fascinating about this faculty of negation in language.

It has been often asserted that there is nothing in speech of which the idea

is not borrowed from the outer world. But where in the outer world is there

such a thing as a negative? Where is the natural phenomenon that would

suggest to the human mind the idea of negation? There are, it is true, many

appearances that may supply types of negation to those who are in search of

them. They who are in possession of the idea of negation may fancy they see

it in nature, in such antitheses as light and shade, day and night, joy and

sorrow. But they only see a reflection of their own thought. There is no

negative in nature. All nature is one continued series of affirmatives; and

if this is too rigid, it is so only because the very term ' affirmation ' is

a relative one, and implies negation: in other words, the expression is

improper only because of the lack of such a foil in nature as negation

supplies in the world of mind. Negation is a product of mind. The first crude

hint of it is seen in the mysterious analogies of instinct. A horse that has

put his head into his manger and found nothing there but chaff, gives a toss

and a snort that are strongly suggestive of negation. It is a case of

expectation baulked. The negative in speech seems to be of this kind. Man is

essentially a creature of special pursuits and limited aims. Everything in

the world but that which he is at the time in |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (l) FLAT. 477

search of is a Nay to him. Call it the smallness and narrowness of his

sphere, or call it the divine, the creative, the purposeful, which out of the

vast realm of nature carves for itself a route, a course, a direction it is

to this intentness of man that every obstacle, or even every neutral and indifferent

thing, becomes contrasted with his momentary bent, and awakens the sense of a

Negative in his mind. 511. The last great feature that rose in our path was

the Indefinite Article. Nothing could be easier to understand how it came and

what it was derived from; indeed, it seems the most obvious and natural thing

in the world. One might almost imagine it to be unavoidable. And yet it is a

rare possession, and a peculiar feature of modern languages. On the other

hand, the Negative is exceedingly mysterious in its nature and sources, and

yet it seems to be common to all human speech, and to be as familiar at the

earliest stage of primitive barbarism, as in the most cultured languages of

the civilised world. I have never heard of a language that had no negative.

But I have heard of native dialects in Australia, in which the negatives have

been selected as the features of distinction, and have set the names by which

the races named themselves, and were known to others 1: just as the two old

dialects of the |

|

|

|

|

|

47^ VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

French language were distinguished by their several affirmatives, and were

called Langue d'oil and Lengua cCoc. 512. Negation then being a sentient

product, a subjective thing at its very root, we ask with curiosity out of

what materials its formula was first made. Of this I have no opinion whatever

to offer. But of the probable history of the N-formula I will boldly give my

own notion, not so much from confidence in its certainty, as for the

incidental illustration which will thus be called out. My conjecture is, that

our N-particle is the relic of some such a word as one, or an, or any, three

words which, as the student knows, are radically identical. I conceive that

of the primitive formula of negation we know nothing, or only know that it

has perished. Like the primitive oak, it has passed away; but it has left

others instinct with its organism. Men are markedly emphatic in denial, and hence

such formulas as not one, not any, not at all, not a bit, not a scrap, not in

the least. See how any echoes back, and that with an emphasis, the antecedent

negative: We come back to Sir Roundell Palmer's suggestion, and repeat the

inquiry whether a majority is never to be allowed any rights or privileges?

March 26, 1870. Hence too, in French, the pas and point, which back up the

negation, also rien and aucun and jamais, and other indifferent words which

by long contact with the negative, like steel from the company of the

loadstone, have got so instinct with the selfsame force that they often

figure as negatives sole. Thus pas encore, point du tout; while the other

three are so well known as negatives, that when they stand alone they are

hardly ever anything else. Yet none of these words possess by right of

extraction the slightest negative signification. 513. The fact seems to be

that the word which is added |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (i) FLAT. 479

for the sake of emphasis, comes to bear the stress of the function by the

mere virtue of its emphasis, and often ends by supplanting its principal. As

in French we see but one or two extant relics of negation without the

subjoined adverb, and as the subjoined adverb has in many instances grown

into a recognised negative in its own right, so there is every reason to

apprehend that but for the conservative influences of literature, the ne

would have been by this time very much nearer to vanishing from the languages

than it actually is. And, had this happened, it would have been only a

repetition of that process in which I conceive ne to have formerly borne the

converse part of the action. Ne is probably the relic of some adverbial

pronoun, which at first served a long apprenticeship under some still more

ancient and now quite forgotten negative, of whose function it long bore the

stress and emphasis, until at length it became the sole substitute. 514. The

Welsh dim, which means ' no,' ' none,' is well known in the familiar answer

dim Saesoneg, which means * no Saxon,' or, 'I don't speak English.' Now this

word dim is merely the word for thing. Fob means ' every/ and pob ddim is the

Welsh for c everything.' Thus, in modern Greek, the negative 8ev is the relic

of ovdev, ' not one ': the not has perished, and the one is now the negative.

As a further illustration it may be added that it is common for rustic

arithmeticians to call the tenth cipher, the Zero or Nought, by the name of

Ought, thus retaining only that part of the word which is purely affirmative

by extraction. Nought is an abbreviation for nan-wuht, ' no-whit '; and the

verbal negative not is but a more rapid form of nought. The answer No! is a

curt form of none, Saxon nan, and is plainly a Flat Adverb. |

|

|

|

|

|

4 Hq VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

la) Of the Flexional Pronoun-Adverbs. B16 Under this head come such old

familiar forms a, hen there where, when, then, henee, whenee, how, why,

father S^hich are ancient flexional forms that sprang from nronouns of the

substantival and adjectival classes. The HdnTof some of these to their origin

is a matter of obleure antiqmt,: others are clear; hut the enquiry belongs

rather to Saxon than to English philology. Jfve search back into the growth

of these, we shah find that h y a e old cases, genitive, dative, accusative,

ablauve. F o "stance, why is an old ablative; and so also , rs tke when

" sav ' so much the better,' like the Latm eo Th s » lonj the

demonstratives what wky is among the relatwes, and its old form is thi or Of,

487. Ttt these Cases are now obscure, and the omy au |

|

|

|

|

|

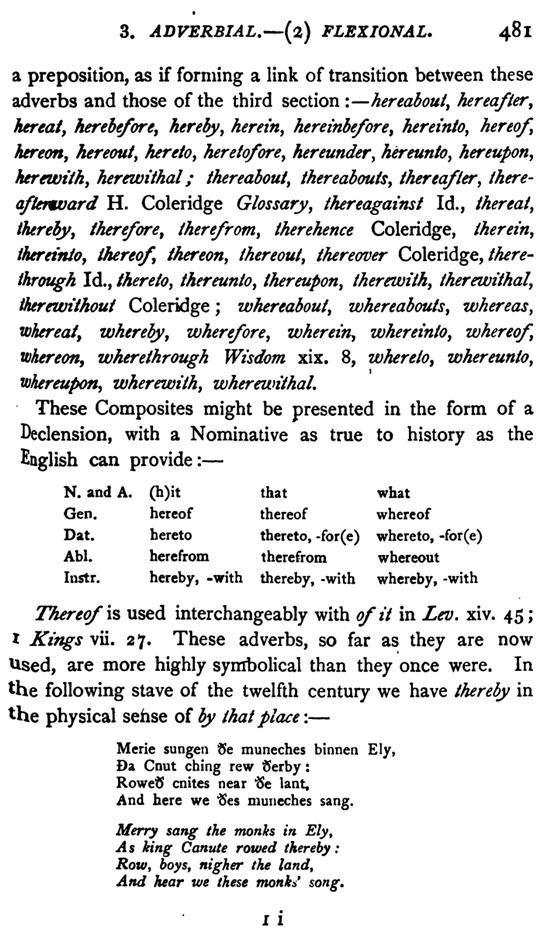

3. ADVERBIAL. (2) FLEXIONAL.

481 a preposition, as if forming a link of transition between these adverbs

and those of the third section -.hereabout, hereafter, hereat, herebefore,

hereby, herein, hereinbefore, hereinto, hereof, hereon, hereout, hereto,

heretofore, hereunder, hereunto, hereupon, herewith, herewithal; thereabout,

thereabouts, thereafter, thereafterward H. Coleridge Glossary, thereagainst

Id., thereat, thereby, therefore, therefrom, therehence Coleridge, therein,

thereinto, thereof, thereon, thereout, thereover Coleridge, therethrough Id.,

thereto, thereunto, thereupon, therewith, therewithal, therewilhout

Coleridge; whereabout, whereabouts, whereas, whereat, whereby, wherefore,

wherein, whereinto, whereof, whereon, wherethrough Wisdom xix. 8, whereto,

whereunto, whereupon, wherewith, wherewithal. These Composites might be

presented in the form of a Declension, with a Nominative as true to history

as the English can provide: N. and A. (h)it that what Gen. hereof thereof

whereof Dat. hereto thereto, -for(e) whereto, -for(e) Abl. herefrom therefrom

whereout Instr. hereby, -with thereby, -with whereby, -with Thereof is used

interchangeably with of it in Lev. xiv. 45; 1 Kings vii. 27. These adverbs,

so far as they are now used, are more highly symbolical than they once were.

In the following stave of the twelfth century we have thereby in the physical

sense of by that place: Merie sungen Se muneches binnen Ely, Da Cnut ching

rew Serby: RoweS cnites near "Se lant, And here we '5es muneches sang.

Merry sang the monks in Ely, As king Canute rowed thereby: Row, boys, nigher

the land, And hear toe these monk*' so.-ig. i i |

|

|

|

|

|

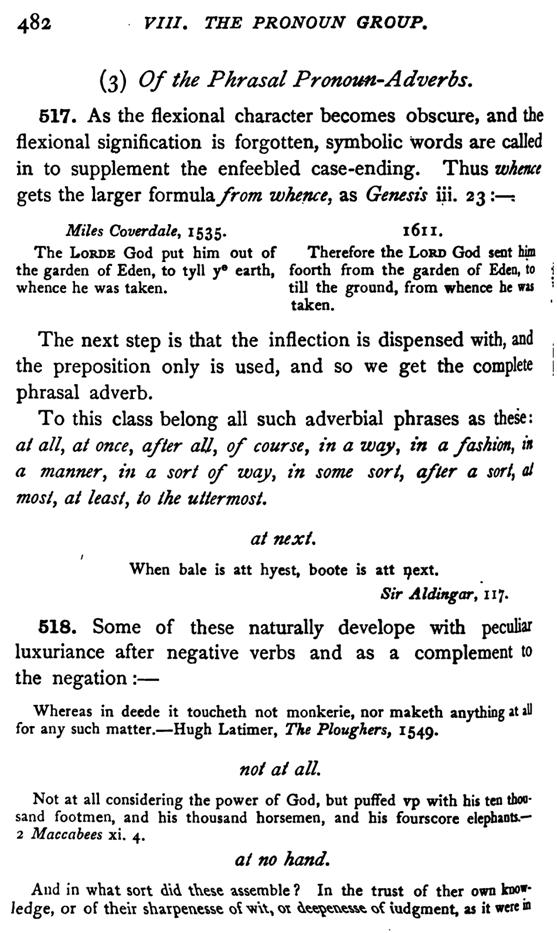

4 g 2 VIII. THE PRONOUN GROUP.

(3) Of the Phrasal Pronoun-Adverbs. 517. As the flexional character becomes

obscure, and the flexional signification is forgotten, symbolic «££*« in to

supplement the enfeebled case-endmg. Thus whence gets the larger

formula/^;" whence, as Genesis 111. 23 , , l6ll. Miles Cover dale,

i53o- . T r A ,f. n t him * f Therefore the Lord (joa sent nun The

Lords God Ijt^ fo J t h h e t° m the garde n of Eden, to the garden of Eden,

to tyll y eartn, i ^ ^ ^ m whence he was whence he was taken. taken. The next

step is that the inflection is dispensed with, and the Pre^osition'only is

used, and so we get the complete ^Tlh-'lss belong all such adverbial phrases

as these: all, at once, after all, of course, in a way mjJUm a manner, in a

sort of way, in some sort, after a sort, most, at least, to the uttermost. at

next. When bale is att hyest, boote is att next. Sir Aldingar, 117. 518. Some

of these naturally develope with peculiar luxuriance after negative verbs and

as a complement to the negation: Whereas in deede it tooeheth not monkerie,

nor maketh anything at all fori"; "eh matter.-Hogh Latimer, The

Ploughs, ,549 |

|

|

|

|

|

3. ADVERBIAL. (3) PHRASAL. 483

an arme of flesh? At no hand. They trusted in him that hath the key of Dauid,

opening and no man shutting; they prayed to the Lord. The Translators to

the Reader, 1611. Some of the phrasal adverbs have assumed the form of single

words, by that symphytism which naturally attaches these light elements to

each other. Hence the forms withal, whatever, nevertheless, notwithstanding,

likewise for ' in like wise.' contrariwise. Not rendring euill for euill, or

railing for railing: but contrarywise blessing. 1 Peter iii. 9. at

leastwise. And every effect doth after a sort contain, at leastwise resemble,

the cause from which it proceedeth. Richard Hooker, Of the Laws &c. I.

v. 2; also id. II. iv. 3. Upside-down is an adverb that has been altered by a

false light from up-so-down, or, as Wiclif has it, up-se-doivn, wherein so or

se is the old relative, 471, and the expression is equivalent to

up-what-down. He is traitour to God & turnej) be chirche upsedown. John

Wiclif, Three Treatises, ed. J. H. Todd, Dublin, 1851, p. 29. Thus es this

worlde torned up-so-downe. Halliwell, v. Upsodoun. which way, that way. Marke

which way sits the Wether-cocke, And that way blows the wind. Ballad Society,

vol. i. p. 344. 519. The progress of modern languages, turning as it does in

great measure upon the development of the symbolic element, naturally sets

towards the production of grouped expressions, and this displays itself with

particular activity in the adverbial parts of language, whether they be

presentively or symbolically adverbial, that is to say, whether 1 i 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

484 vnI - THE PR0N0VN GR0UP the

nounal or the pronounal character is prevalent. For the tendency of novelty

is to show itself prominently m the adverbs of either category, much on the

same prmc.ple as the extremities of a tree are the first to display the

newest movements of growth. The adverbs are the tips or extremities of all

that is material in speech. |

|

|

|

|

|

CHAPTER IX. THE LINK-WORD GROUP.

520. Under the title of Link-word I comprise all that vague and flitting host

of words which, starting forth from time to time out of the formal ranks of

the previous parts of speech to act as the intermediaries of words and

sentences, are commonly called Prepositions and Conjunctions. These two parts

of speech have a certain fundamental identity, combined with a bold

divergence in which they appear as perfectly distinct from one another. Their

distinction is based on the definition that prepositions are used to attach

nouns to the sentence, and conjunctions are used to attach sentences or

introduce them. The neutral ground on which they meet, and where no such

discrimination is possible, is in the generic link-words and, or, also, for,

but, than. 1. Of Prepositions. 521. The preposition may be defined as a word

that expresses the relation of a noun to its governing word. A few examples

must suffice for the illustration of a class of words so familiarly known and

so various in their shades of signification. The examples will be mostly of

the less common uses, as we shall consider the common uses to be |

|

|

|

|

|

486 IX. THE LINK- WORD GROUP.

familiar to the mind of the reader; the object being to suggest the almost

endless variety of shades of which prepositions are susceptible. First, the

prepositions of the simpler and mostly elder sort. Flat Prepositions. At. Now

used only (in its restful sense) of time and place, but formerly also with

reference to persons: I may take my leaue att you all! the flower of

Manhoode is gone from mee! Fjlodden Ffeilde, 171. ' for the great kindnesse I

haue found att thee, fforgotten shalt thou neuer bee. Eger and Grime, 1 343.

by. But say by me as I by thee, I fancie none but thee alone. Ballad Society,

vol. i. p. 244. I think he will consider it a right thing by Mrs. Grant as

well as by Fanny. Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, ch. v. Where we should now

say ■ as regards Mrs. Grant/ or ' as far as Fanny is concerned/ 522.

By having originally meant about, acquired in certain localities a power of

indicating the knowledge of something bad about any person, insomuch that ' I

know nowt by him ' is provincially used for ' 1 know no harm of him.' And it

is according to this idiom that in our version St. Paul witnesses of himself,

' I know nothing by myself, yet am I not hereby justified': and the

expression occurs more than once in the curious book from which the following

is quoted: |

|

|

|

|

|

1. PREPOSITIONS. 487 Then I was

committed to a darke dungeon fifteene dayes, which time they secretly made

enquiry where I had lyen before, what my wordes and behauiour had beene while

I was there, but they could find nothing by me. Webbe his trauailes, 1590.

But still exists as a preposition in the connections no one but, nothing but

No two objects of interest could be more absolutely dissimilar in kind than

the two neighbouring islands, Staffa and Iona: Iona dear to Christendom for

more than a thousand years; Staffa known to the scientific and the curious

only since the close of the last century. Nothing but an accident of

geography could unite their names. The Duke of Argyll, Iona, in it. for.

Wherefore getting out again, on that side next to his own House; he told me, I

should possess the brave Countrey alone for him: So he went his way, and I

came mine. Pilgrim's Progress, facsimile ed. p. 35. like. Out of that great

past he brought some of the sterner stuff of which the martyrs were made, and

introduced it like iron into the blood of modern religious feeling. J. C.

Shairp, John Keble, 1866. nigh. There shall no euell happen vnto the, nether

shall eny plage come nye thy dwellyng. Psalm xc. 10 (1539). 523. Of is the

most frequent preposition in the English language. Probably it occurs as

often as all the other prepositions put together. It is a characteristic

feature of the stage of the language which we call by distinction English, as

opposed to Saxon. And this character, like so many characters really

distinctive of the modern language, is French. Nine times out of ten that of

is used in English it represents the French de. It is the French preposition

in a Saxon mask. The word of is Saxon, if by ' word' we understand the two

letters o andy^ or the sound they make when |

|

|

|

|

|

488 IX. THE LINK-WORD GROUP.

pronounced together. But if we mean the function which that little word

discharges in the economy of the language, then the ' word ' is French at

least nine times out of ten. Where the Saxon of was used, we should now

mostly employ another preposition, as Alys us of yfle. Deliver us from evil.

The following from the Saxon Chronicle, a.d. 894, shews one place where we

should retain it, and one where we should change it: Ne cum se here oftor

eall ute of The host came not all out of the baem setum ponne tuwwa. opre

sipe encampment oftener titan twice: once pa hie aerest to londe comon. ser

when they first to land came, ere the sio herd gesamnod wsere. opre sipe

Fierd was assembled: once when pa hie of paem setum faran wol- they would

depart from the encamp don. ment. Thus the Saxon of has to be sought with

some scrutiny by him who would find it in modern English. There was indeed

one use in which it already coincided with French de, namely, as the link

between the passive verb and the agent. Though we employ this Saxon of no

longer, though by has entirely superseded it in this function, our ears are

still familiar in Bible English with this passival of: . When thou art

bidden of any man to a wedding, sit not downe in the highest rourae: lest a

more honourable man then thou be bidden of him. Luke xiv. 8. Paul after his

shipwreck is kindly entertained of the barbarians. Acts xxviii. (Contents.)

I follow after, if that I may apprehend that for which also I am apprehended

of Christ Iesus. Phil. iii. 12. As before said, the common and current of

which is so profusely sprinkled over every page, is French in its inward

essence. Numerous as are the places in which this preposition now occurs, it

is less rife than it was. In the fifteenth |

|

|

|

|

|

1. PREPOSITIONS. 489 and

sixteenth centuries the language teemed with it. It recurred and recurred to

satiety. This Frenchism is now much abated. I will add a few examples in

which we should no longer use it. How shall I feast him? What bestow of him?

Twelfth Night, iii. 4. 2. What time the Shepheard, blowing of his nailes. 3

Henry VI, ii. 5. 3. Doe me the favour to dilate at full, What haue befalne of

them and thee till now. Comedy of Errors, i. 1. 124. In the Fourth Folio this

last of is at length omitted. 524. Off, a modified of, is now little used

prepositionally; it is mostly reserved for such adverbial uses, as be off,

take off, wash off, write off, they who are far off. But this is a modern

distinction, and it exhibits one of the devices of language for increasing

its copia verborum. Any mere variety of spelling may acquire distinct

functions to the enrichment of speech. In Miles Coverdale's Bible (1535)

there is no sense-distinction between <?/~and off: as may be seen by the following

from the thirteenth chapter of the prophet Zachary: In that tyme shall the

house off Dauid and the citesyns off Ierusalem haue an open well, to wash of

synne and vnclennesse. And then (sayeth the Lorjde off hoostes) I will

destroye the names of Idols out off the londe. On and its compound upon. . .

. and layde him on the Altar vpon the wood. Genesis xxii. 9. upon. There

were slaine of them, vpon a three thousand men. 1 Maccabees iv. 15. And if

any will judge this way more painfull, because that all things must be read

upon the book, whereas before by the reason of so often repetition they could

say many things by heart: if those men will weigh their |

|

|

|

|

|

490 IX. THE LINK- WORD GROUP.

labour, with the profit and knowledge which daily they shall obtain by

reading upon the book, they will not refuse the pain, in consideration of the

great profit that shall ensue thereof. Old Common Prayer Book, The Preface.

over. In a series of Acts passed over the veto of the President, Congress

provided for the assemblage in each Southern State of a constituent

Convention, to be elected by universal suffrage. 525. Till is from an ancient

substantive til, still flourishing in German in its rightful form as jiel,

and meaning goal, mark, aim, butt. Thus in some Saxon versified proverbs, Til

sceal on e'Sle domes wyrcean. Mark shall on patrimony doom-wards work. Two

Saxon Chronicles Parallel, p. xxxv. i.e. a borne or landmark shall be

admissible as evidence. For its prepositional use, see the quotation from R.

Brunne in 515. This preposition is now appropriated to Time: we say till

then, till to-morrow; but not //// there. Earlier it was used of Place, as in

the Passionate Pilgrim: She, poor bird, as all forlorn, Lean'd her breast

up till a thorn, And there gan the dolefull'st ditty, That to hear it was

great pity. This preposition enjoys a provincial function which is unknown in

literature: Well, Hester, do you feel tired now that there are two sets of

lodgers in the house? Yes, Sir, till night I do. (Clevedon, Somersetshire.)

to ( = comparable to). A sweet thing is love, It rules both heart and mind;

There is no comfort in the world To women that are kind. Ballad Society, vol.

i. p. 320. |

|

|

|

|

|

1. PREPOSITIONS. 491 With. This

preposition had a value in the fourteenth century which is unknown in Saxon

and which did not permanently root itself in English. It was used like the by

of passivity, as Who saved Daniel in the horrible cave, Ther every wight,

save he, master or knave, Was with the leon frette, or he asterte? The Man of

Lawes Tale, 4895. i. e. was devoured by the lion before he could stir. The

isolation of this use at a particular point in our literature leads to the

supposition that it may have been Danish, especially as this is the use of

Danish ved to this day *. 526. The prepositions are more elevated in the

scale of symbolism than the pronouns. They are quite removed from all

appearance of direct relation with the material and the sensible. They

constitute a mental product of the most exquisite sort. They are more cognate

to mind; they have caught more of that freedom which is the heritage of mind;

they are more amenable to mental variations, and more ready to lend

themselves to new turns of thought, than pronouns can possibly be. To see

this it is necessary to stand outside the language; for these things have

become so mingled with the very circulation of our blood, that we cannot

easily put ourselves in a position to observe them. Those who have mastered,

or in any effective manner even studied Greek, will recognise what is meant.

To see it in our own speech requires more practised habits of observation.

But here I can avail myself of testimony. Wordsworth had the art of bringing

into play the subtle powers of English prepositions, 1 It is the preposition

used in title-pages before the author's name, as 1 Bjowulfs Drape. Et

Gothisk Helte-Digt af Angel-Saxisk paa Danske Riim ved Nic. Fred. Sev.

Grundtvig, Praest. Kjobenhavn, 1 820.' Beowulf's Death. A Gothic Hero-Poem

from Anglo-Saxon, in Danish Rime, by N. F. S. Gruntvig, Priest. Copenhagen,

1820. |

|

|

|

|

|

49 ^ IX > THE LINK-WORD

GROUP. and this feature of his poetry has not escaped the notice of Principal

Shairp. ' Here, in passing, I may note the strange power there is in his

simple prepositions. The star is on the mountain-top; the silence is in the

starry sky; the sleep is among the hills; the gentleness of heaven is on the

sea.' Studies in Poetry and Philosophy ', p. 74. Wordsworth dedicated his

Memorials of a Tour in Italy to his fellow-traveller, Henry Crabb Robinson.

The opening lines are: * Companion! by whose buoyant spirit cheered, In

whose experience trusting day by day. It was originally written ' To whose

experience/ Mr. Robinson suggested that ' In ' would be better than ' To/ and

the poet, after offering reasons for a thing which can hardly be argued upon,

ended by yielding his own superior sense to the criticism of his friend.

Diary, 1837. Flexional Prepositions. 527. A second series of prepositions are

those in which flexion is traceable; for example, the genitival form, as

against, besides, sithence \ or comparison, as after, near, next. after. Full

semyly aftir hir mete she raughte. Prologue, 136. The vintners were made to

pay licence duties after a much higher scale than that which had obtained

under Ralegh. Edward Edwards, Ralegh (1868), ii. p. 23. besides ( = beyond,

or contrary to). Besides all men's expectation. Richard Hooker, Of the Laws

&c. Preface, ii. 6. sithence. We require you to find out but one church

upon the face of the whole earth, that hath been ordered by your discipline,

or hath not been ordered |

|

|

|

|

|

I. prepositions. 493 by ours,

that is to say, by episcopal regiment, sithence the time that the blessed

Apostles were here conversant. Richard Hooker, Of the Laws &c. Preface,

iv. I. near (comparative of nigh). The fruitage fair to sight, like that

which grew Near that bituminous lake where Sodom flam'd. Paradise Lost, x.

562. next (superlative). Happy the man whom this bright Court approves, His

sov'reign favours, and his country loves, Happy next him, who to these shades

retires. Alexander Pope, Windsor Forest, 235. 528. Perhaps we ought to range

in this series such a preposition as save, which having come to us through

the French sauf, from the Latin salvo, is still, at least to the perceptions

of the scholar, redolent of the ablative absolute. save. In one of the public

areas of the town of Como stands a statue with no inscription on its

pedestal, save that of a single name, volta. John Tyndall, Faraday as a

Discoverer. Another instance of an old participle and a young preposition is

except. . . . with all her unrivalled powers of mendacity, she very rarely

succeeded in deceiving any one except her friends. John Hosack, Mary Queen

of Scots, p. 35. PJirasal Prepositions. 529. A third series of prepositions

are the phrasal prepositions, consisting of more than one word. In the

development of this sort of preposition, we have been expedited by French

tuition. A constant and almost necessary element in their formation is the

preposition of. They are the analogues of such French prepositions as aupres

de, autour de, au lieu de; as |

|

|

|

|

|

494 IX - THE L INK ' W0RD GR0UP

in lieu of. A burnt stick and a barn door served Wilkie in lieu of pencil and

canvas.Samuel Smiles, Self Help, ch. iv. aboard of. Every officer and man

aboard of her entertained unbounded confidence in her qualities. Oct. II,

1870. long of; along of. All long of this vile Traitor Somerset. 1 Henry VI,

iv. 3. 33. Long all of Somerset, and his delay. Ibid. 46. A ruder form of

this preposition was long on or along on, still heard in country places.

Chaucer has I can not tell whereon it was along, But wel I wot gret stryf is

us among. The Canones Yemannes Tale, 16398; ed. Tyrwhitt. out of. ... it

cannot be that, a Prophet perish out of Hierusalem.-L^e xiii. 33 in spighi of; in spite of As on

a Mountaine top the Cedar shewes, That keepes his leaues in spight of any

storme. 2 Henry VI, v. I. 206. in despight of And in despight of Pharao fell,

He brought from thence his Israel. John Milton, Psalm cxxxvi. Antecedent to

this was the genitival formula 'in my despite,' Titus Andronicus, i. a; 'in

your despite, Cymbehnt, i 7; ' in thy despite,' i Henry VI, iv. 1; ' in Love

s desp.te, John Keble, Christian Year, Matrimony. |

|

|

|

|

|

1. prepositions. 495 for . . .

sake (with genitive between). Now for the comfortless troubles' sake of the

needy. Psalm xii. 5. But if any man say vnto you, This is offered in

sacrifice vnto idoles, eate not for his sake that shewed it, and for conscience

sake. 1 Cor. x. 28. For Sabrine bright her only sake. Ballad Society, vol.

i. p. 386. 530. This is the formula throughout the English Bible, and

throughout Shakspeare with three exceptions, according to Mrs. Cowden Clarke.

In the above examples, troubles', his, conscience are in the genitive case.

The s genitival is not added to conscience, because it ends with a sibilant

sound, and where there are two sibilants already, a third could hardly be

articulated. The s of the genitive case is, however, often absent where this

reason cannot be assigned. Thus: For his oath sake. Twelfth Night, iii.

4. For fashion sake. As You Like It, iii. 2. For sport sake. 1 Henry IV,

ii. I. For their credit sake. I Henry IV, ii. I. For safety sake. Id. v.

1. For your health and your digestion sake. Troilus and Cressida, ii. 3.

Instead of this genitive the present use of the language substitutes an of

form, which occurs in Shakspeare three times: for the sake of. And for the

sake of them thou sorrowest for. Comedy of Errors, i. 1. 122. If for the sake

of Merit thou wilt hear mee. Antony and Cleopatra, ii. 7. 54. A little

Daughter, for the sake of it Be manly, and take comfort. Pericles, iii. 1.

21. |

|

|

|

|

|

496 IX. THE LINK -WORD GROUP.

531. Through the phrasal prepositions we are able to see how the older

prepositions came into their place, and (to speak generally) how the symbolic

element sustains itself and preserves itself from the natural decay of

inanition. Here is a presentive word enclosed between two prepositions, as if

it had been swallowed by them, and were gradually undergoing the process of

assimilation. By and bye the substantive becomes obsolete elsewhere, and

lives on here as a preposition, with a purely symbolic power. Thus in despite

of becomes first despite of ' despite of all controversy/ Measure for

Measure, i. 2; ' despite of death,' Richard II, i. 1; and then in a further

stage despite stands alone ' despite his nice fence/ Much Ado, v. 1; '

despite thy victor sword/ Lear, v. 3; and in these latter cases the old

substantive despite is as purely a preposition as the French malgre'. And it

may be added that despite as a substantive is as good as obsolete, except in

poetry, but the prepositional use is well established. 2. Of Con-junctions.

532. Of all the parts of speech the conjunction comes last in the order of

nature. The office of the conjunction is to join sentences together, and

therefore it presupposes the completion of the simple sentence; and as a

consequence it would seem to imply the pre-existence of the other parts of

speech, and to be the terminal product of them all. It is essentially a

symbolic word, but this does not hinder it from comprising within its

vocabulary a great deal of half-assimilated presentive matter. This is a point

to which we shall return in the course of the section. The necessity for

conjunctions (other than and, or, also) does not arise until language has

advanced to the formation |

|

|

|

|

|

2. CONJUNCTIONS. 497 of compound

sentences. Hence the conjunctions are as a whole a comparatively modern

formation. Almost all the conjunctions are recent enough for us to know of