|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5505) (tudalen (delwedd B5505) (tudalen

|

GRAMADEG O IAITH Y

CYMRY. A GRAMMAR OF THE WELSH LANGUAGE. BY WILLIAM SPURRELL. THIRD EDITION.

Carmarti)cn w;l LI AM SP\3”“Y.\.\. %% MDCCCLXX %% SPCRRELL, PRINTER,

CARMAaTRCN. %%%%%% 13 %% GRAMADEG O lAITH Y CYMEY %% GRAMMAR %% OF THE %%

WELSH LANGUAGE %% BT %% WILLIAM SPURRELL %% THIBD EDITION %%

Carmarti)cn w;l LI AM SP\3”“Y.\.\. %% MDCCCLXX %% SPCRRELL, PRINTER,

CARMAaTRCN. %%%%%% 13 %ch %

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5506) (tudalen2 (delwedd B5506) (tudalen2

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5507) (tudalen3 (delwedd B5507) (tudalen3

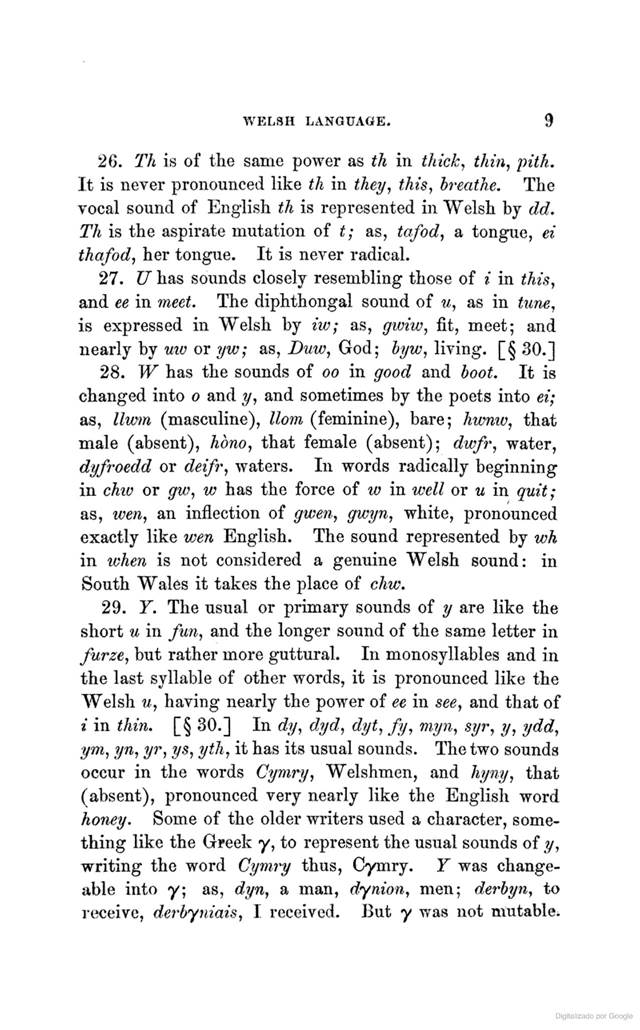

|

TO THE READER. %%

During the interval that elapsed between the publica- tion of the first and

second editions of this Work, the Author took advantage of many opportunities

of adding, not merely to the bulk of the volume, but also, he trusts, to the

utility of. its contents. Many subjects slightly touched on in the first

edition, were in the second discussed more in detail, and some fresh subjects

were brought under notice. This was especially the case with reference to the

Elementary Sounds of the Language, a subject on which little thought had been

expended by Welsh grammarians in general.

The present edition has been further enlarged, by the introduction of a list

of words governing the mutable initials, and of numerous additions throughout

the body of the Work. The contents have also been made more accessible, by

numbering the paragraphs and appending an index of subjects.

May, 1870. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5508) 4 (delwedd B5508) 4

|

ADVERTISEMENT TO

THE FIRST EDITION. %% The Grammar now before the reader owes its publica-

tion to a feeling on the part of the Author that no sufficiently simple work

on the subject on which it treats had ever appeared in print.

To lay claim to great originality in the production of a Welsh Grammar would

be idle, so many writers having canvassed the subject, while the principles

of the language remain unaltered. Equally impossible would it be to

acknowledge the various sources whence the author has derived his

information, notes on the subject having been collected by him during a

period of some years, without any intention of their being published, and

principles elicited by examination of the structure of the language, which at

last accumulated into a mass requiring method only to form into a book.

The Author trusts that the natural arrangement of the Work, and a departure

from some antiquated and fanciful theories, at variance with philology, will

secure, what he has mainly aimed at, the utility of his production. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5509) 5 (delwedd B5509) 5

|

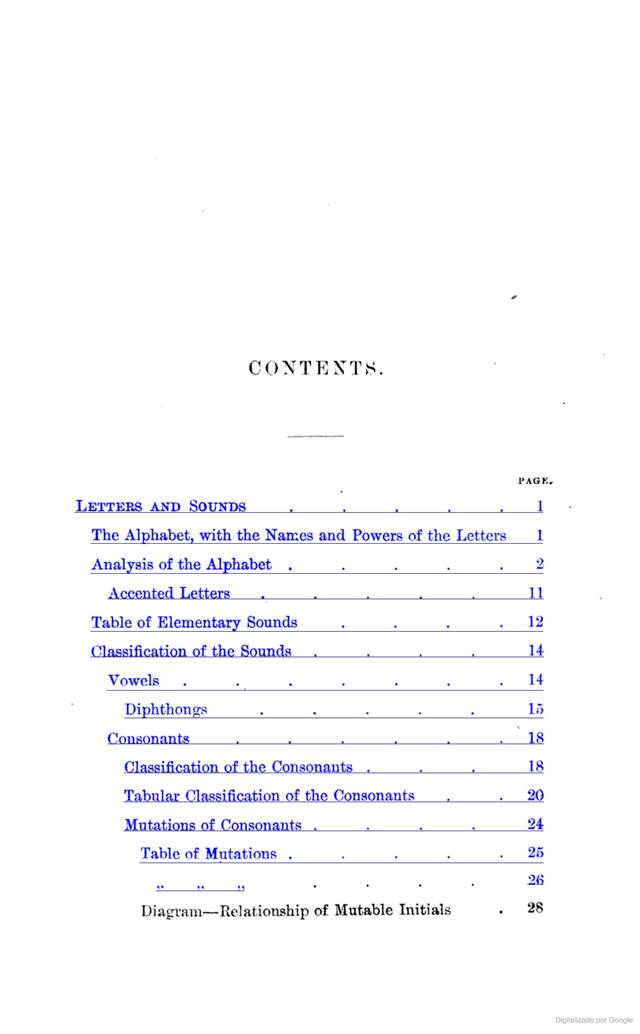

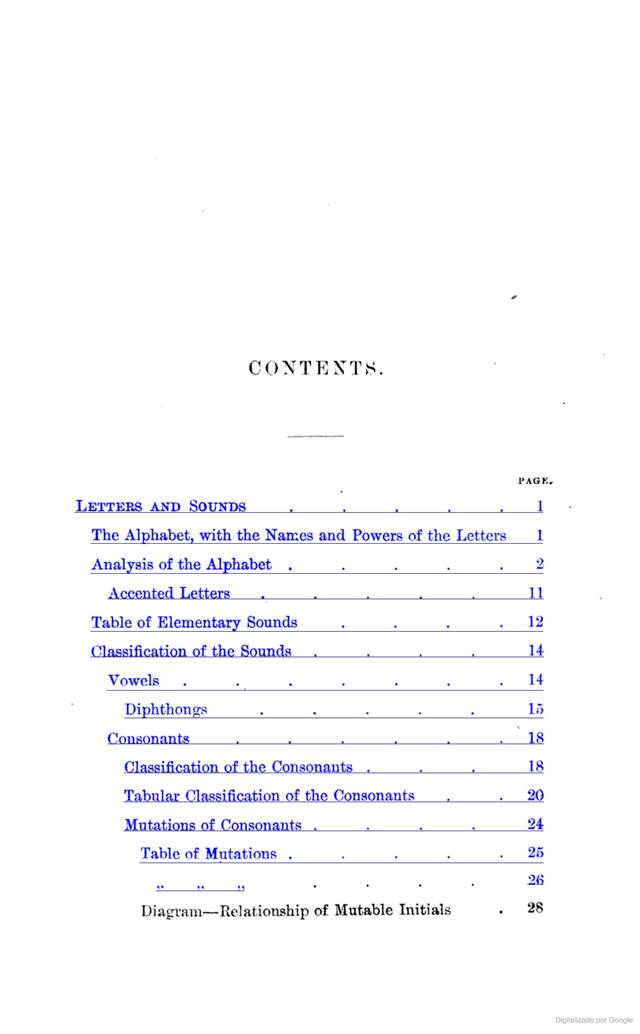

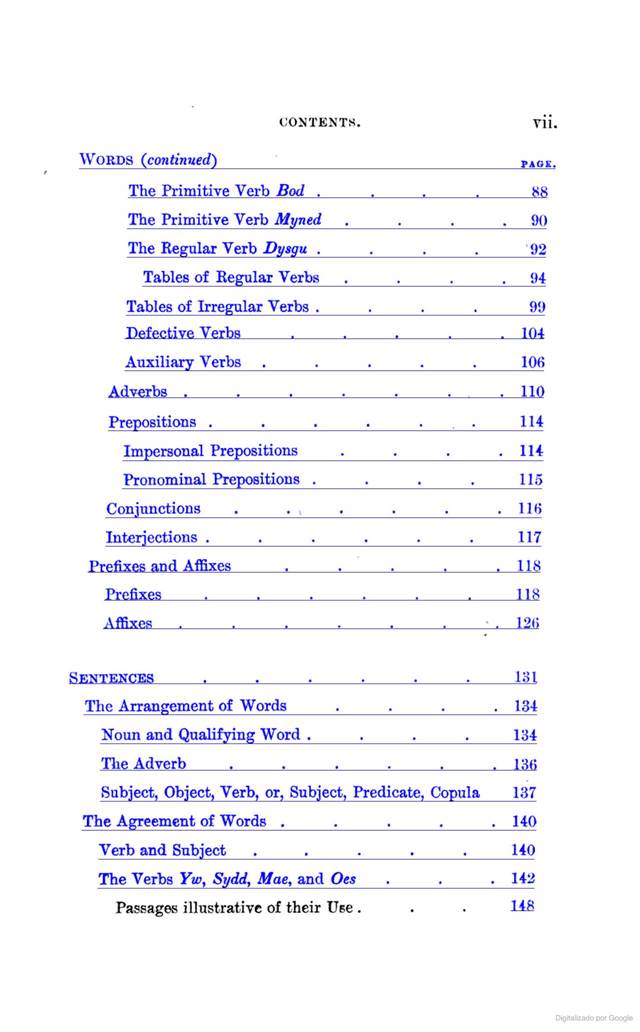

CONTENTS. %% PAQK.

Lettees and Sounds ..... l

The Alphabet, with the Names and Powers of the Letters 1

Analysis of the Alphabet . . . .2

Accented Letters . . . . . ■ 11

Table of Elementary Sounds . . . .12

Classification of the Sounds . . . . 14

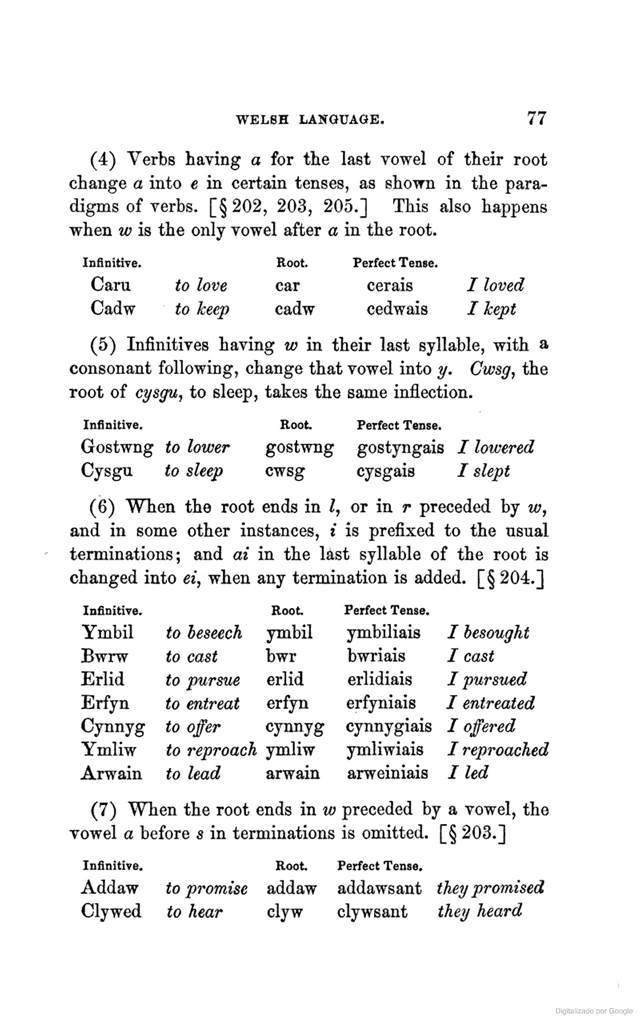

Vowels . . . . . . .14

Diphthongs . . . . . 16

Consonants . . . . . .18

Classification of the Consonants . . . 18

Tabular Classification of the Consonants . . 20 Mutations of Consonants ....

24

Table of Mutations . . . .26

>» » »» .... **>»

Dmgram — Relationship of MutabVe ImWa”a • *”“ %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5510) 6 (delwedd B5510) 6

|

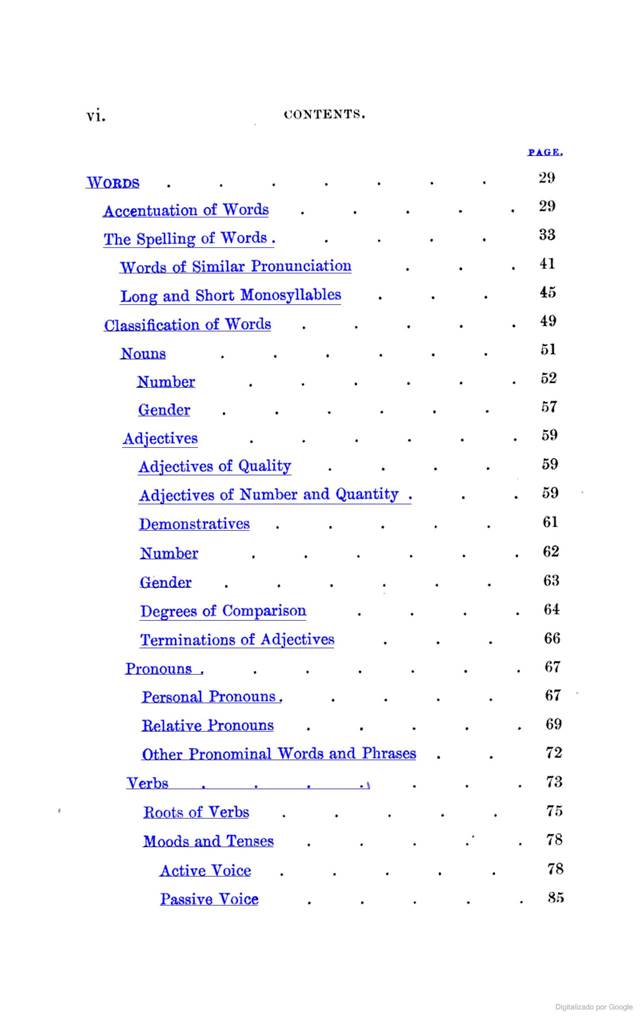

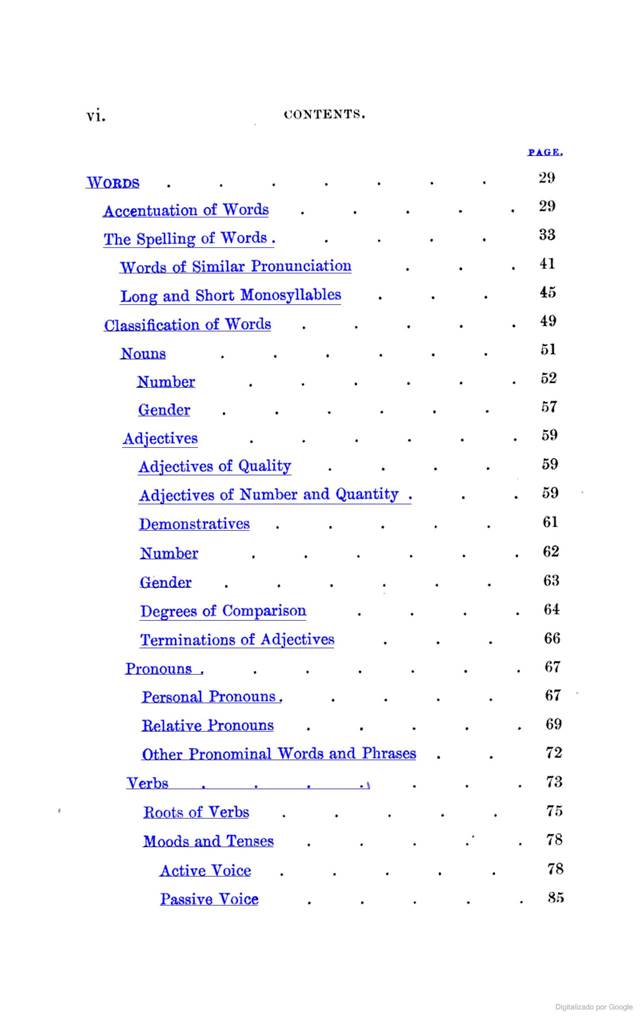

VI. I'ONTKXTS.

PAGK

Words ....... 2V>

Accentuation of Words . . . . .29

The Spelling of Words ..... 38

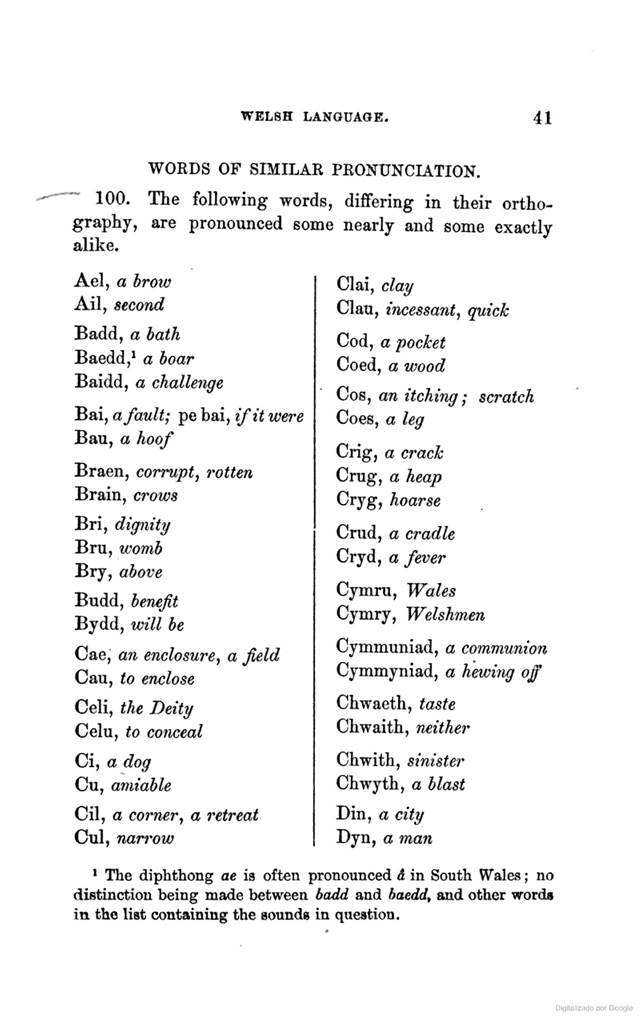

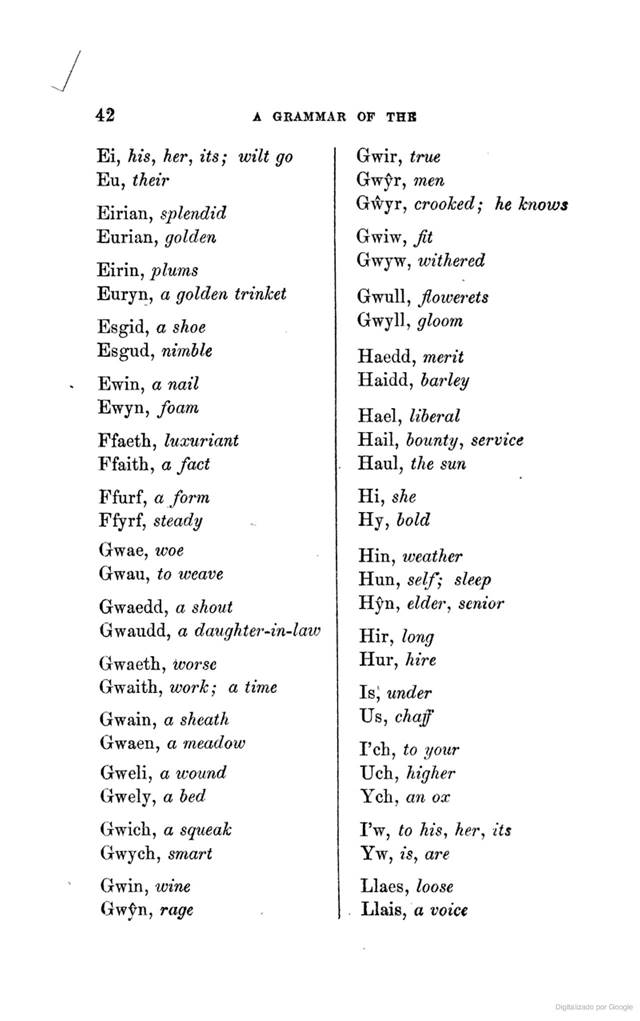

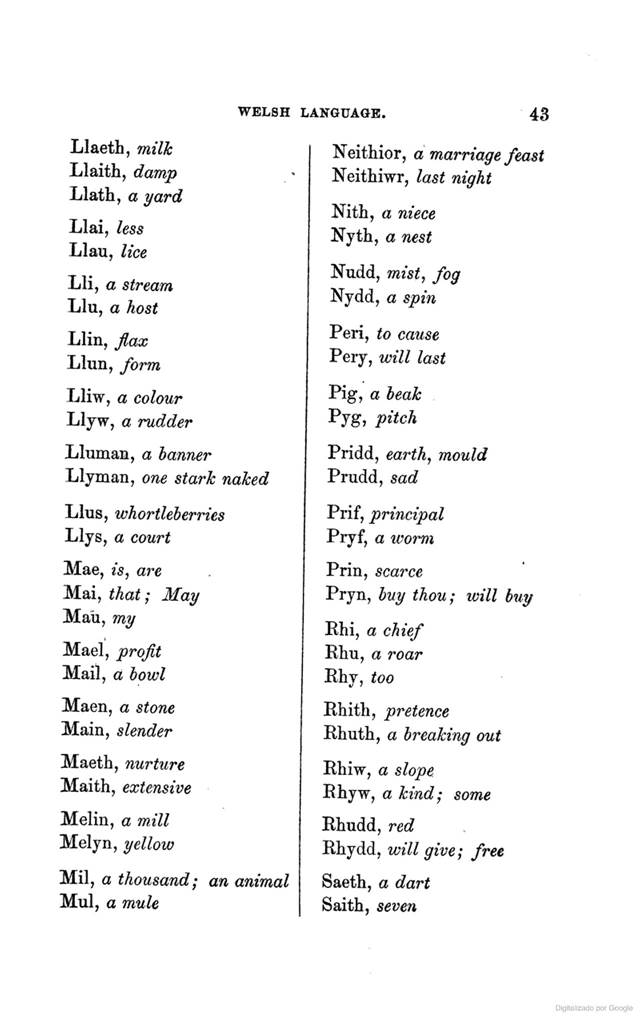

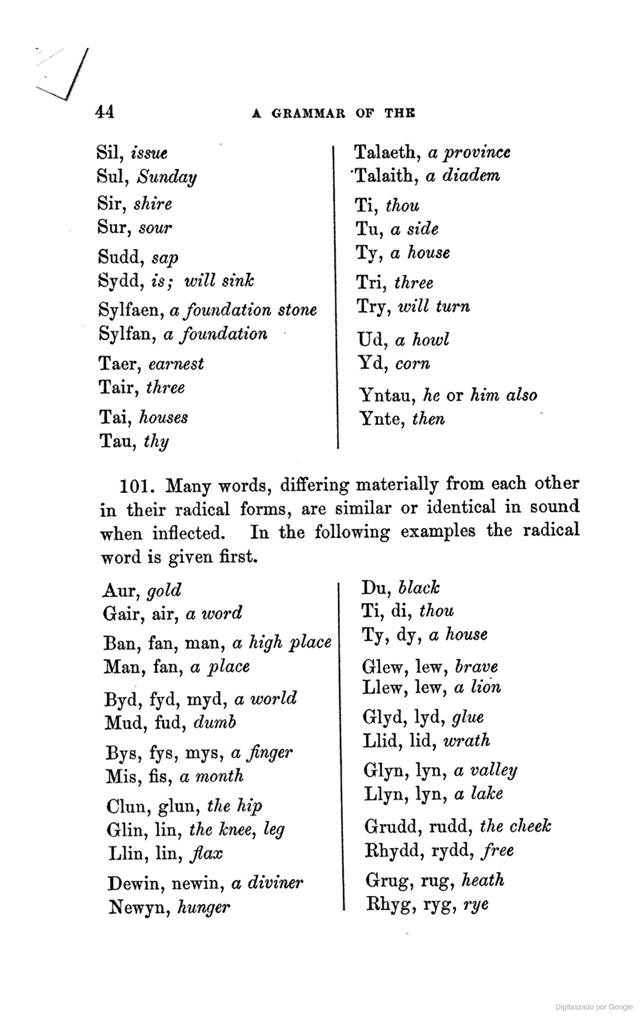

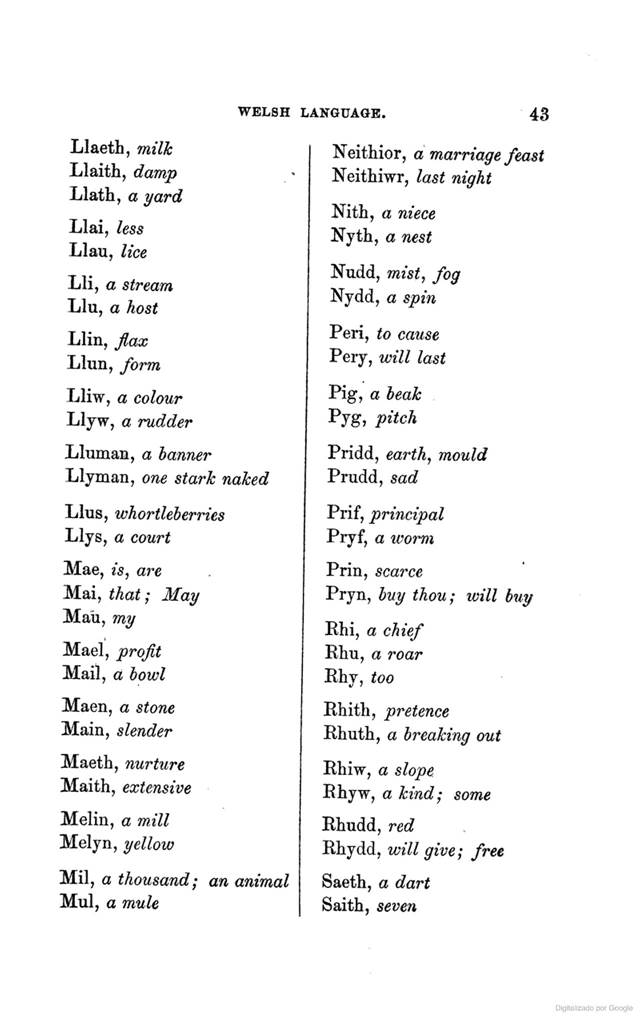

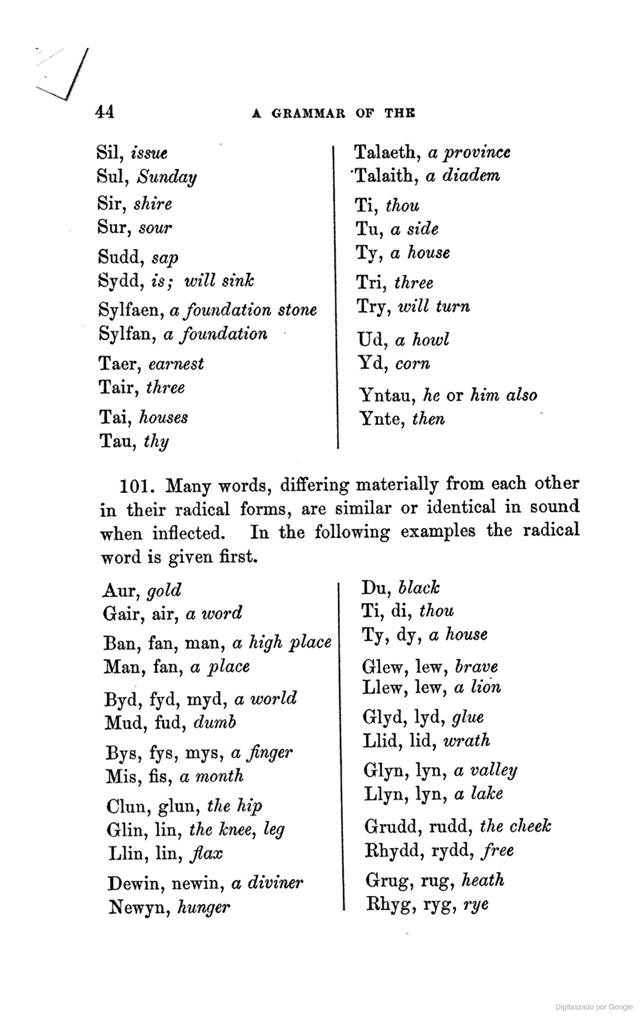

Words of Similar Pronunciation . . .41

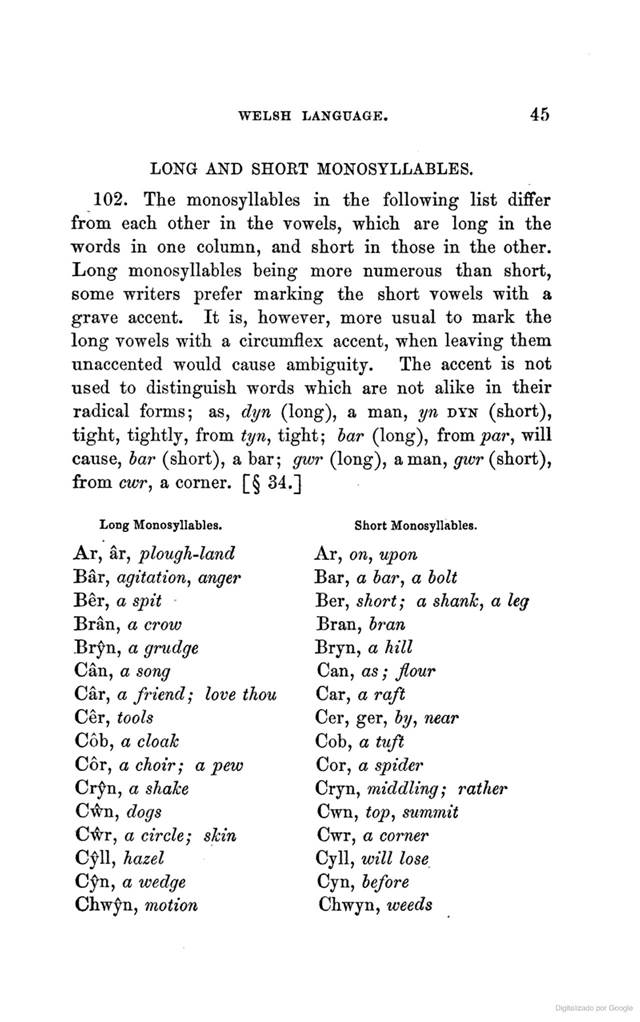

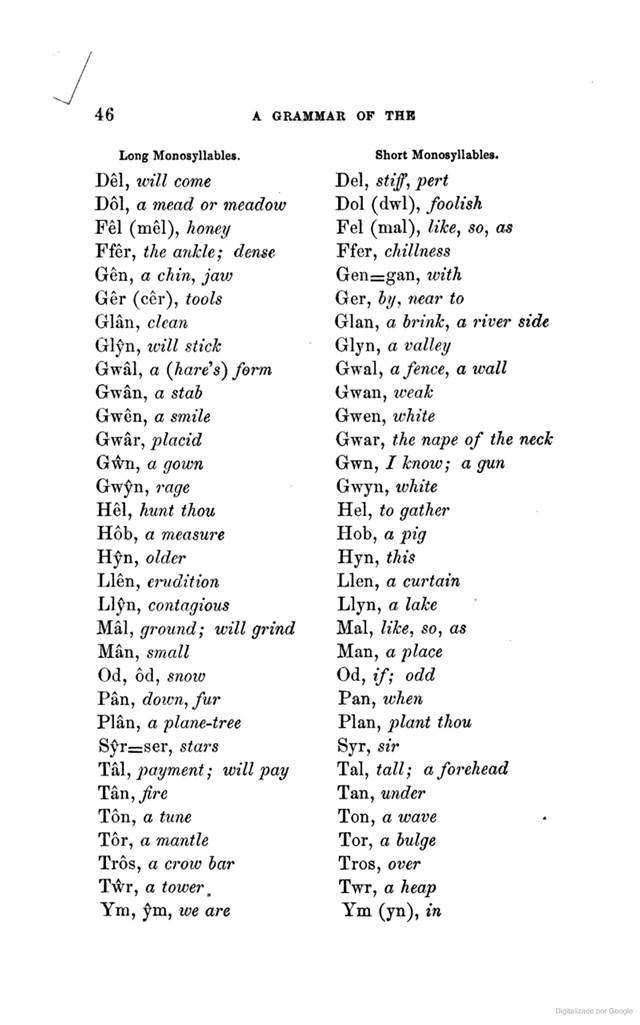

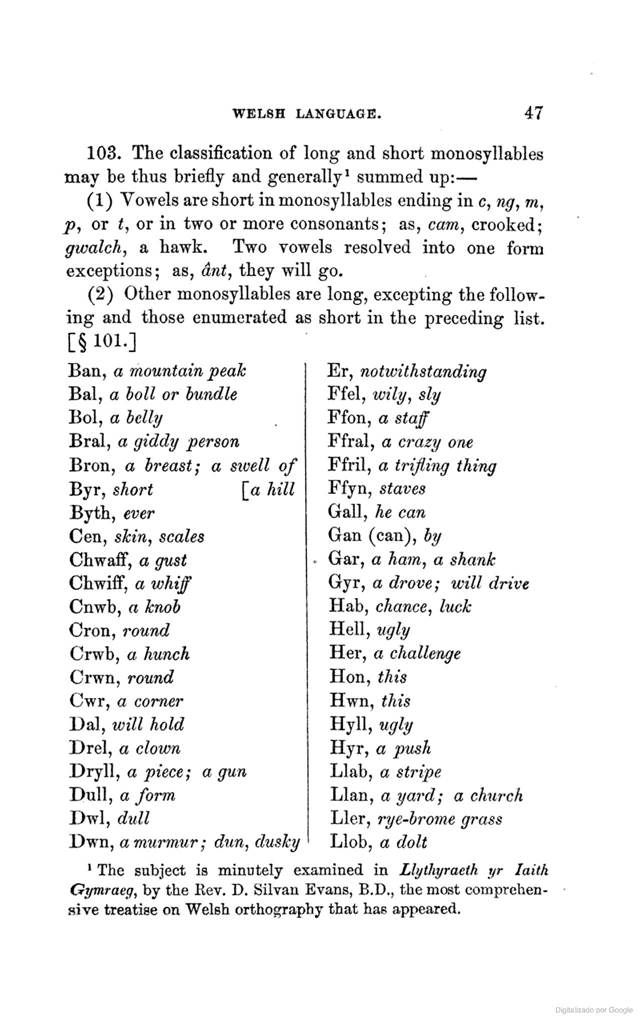

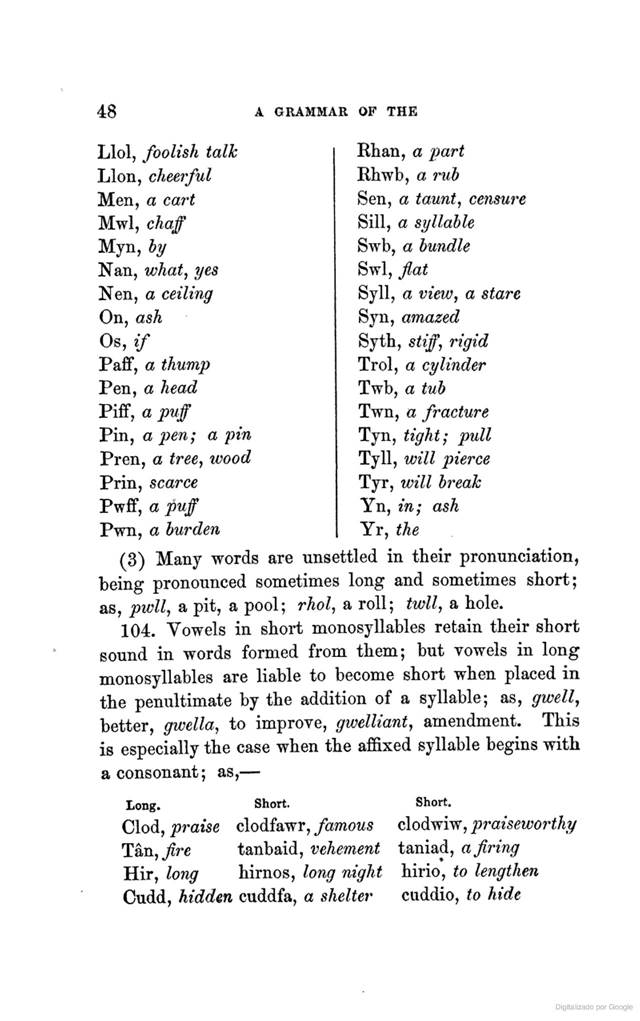

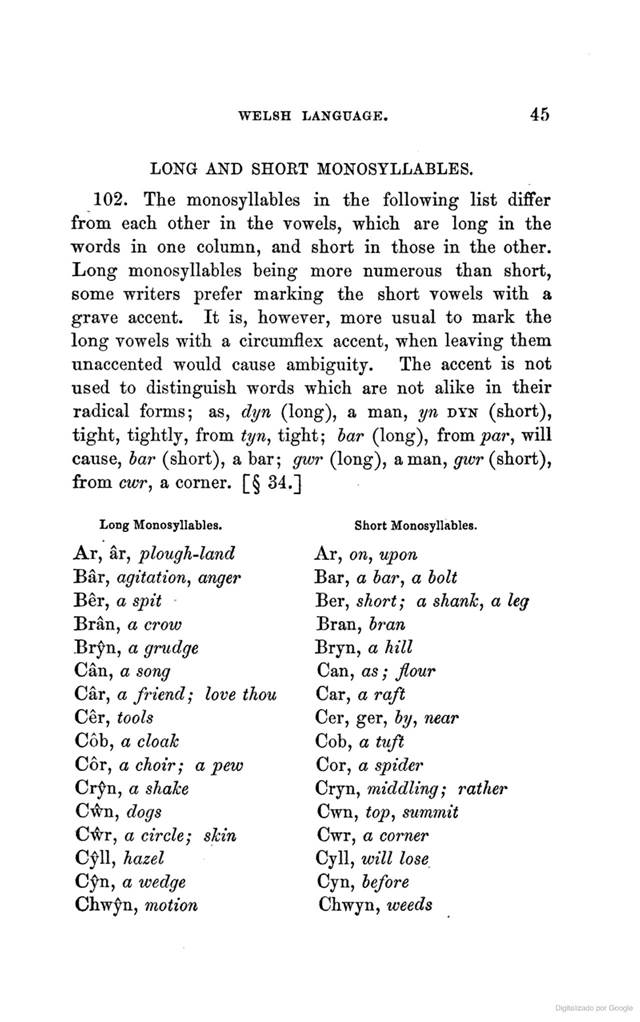

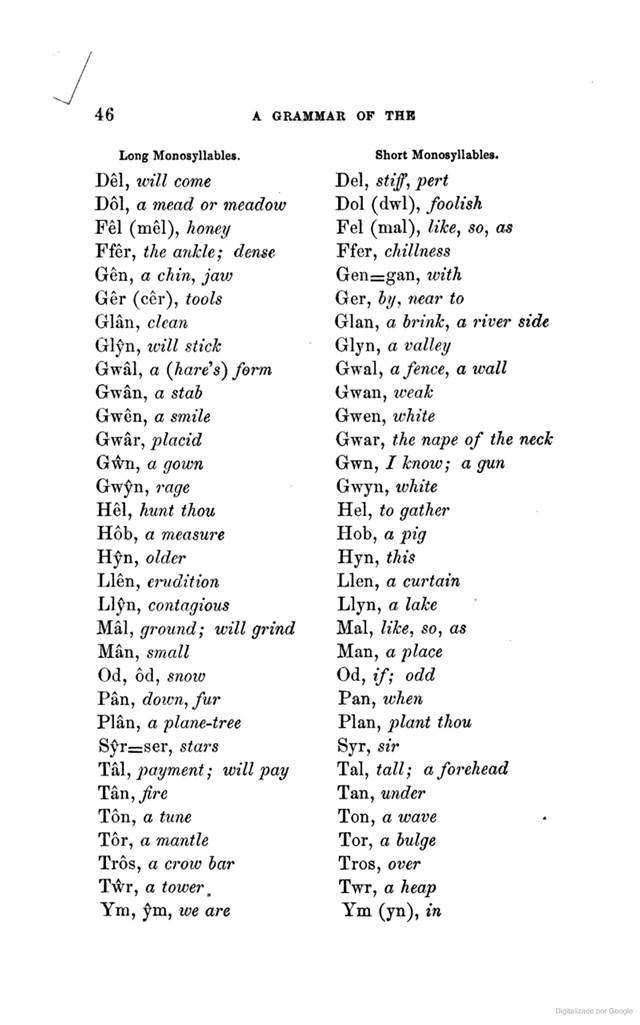

Long and Short Monosyllables . . . 4r>

Classification qf Words . . . . .49

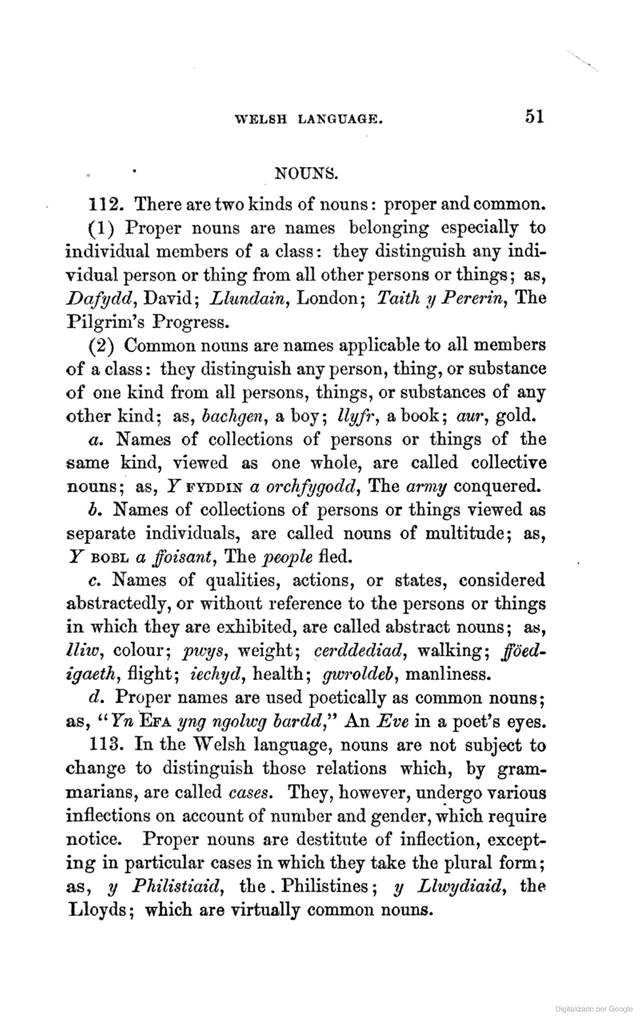

Nouns . . . . . . ol

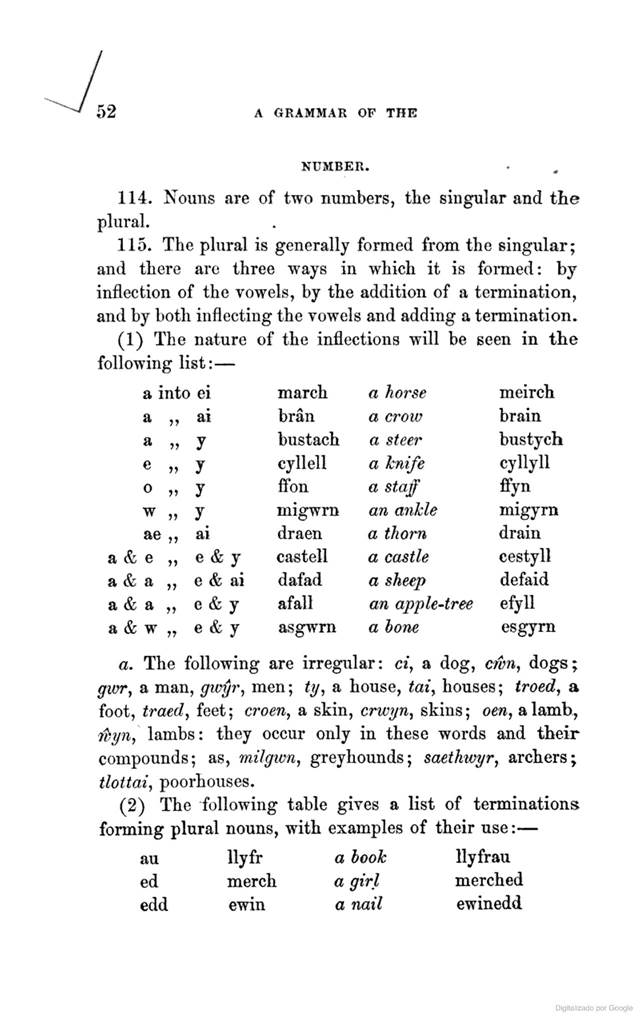

Number . . . . . . r)2

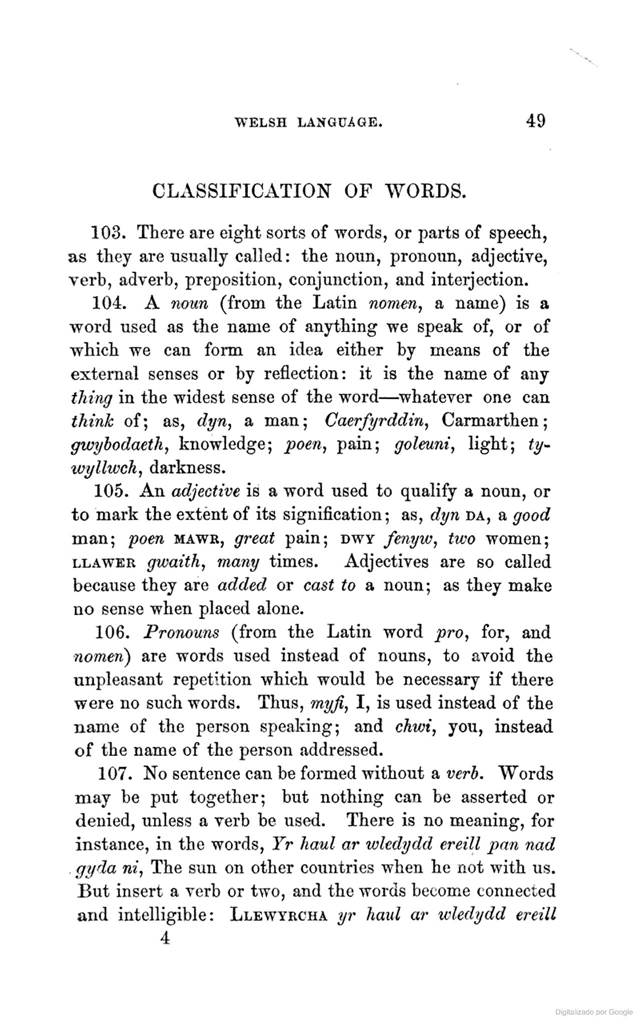

Gender ...... r>7

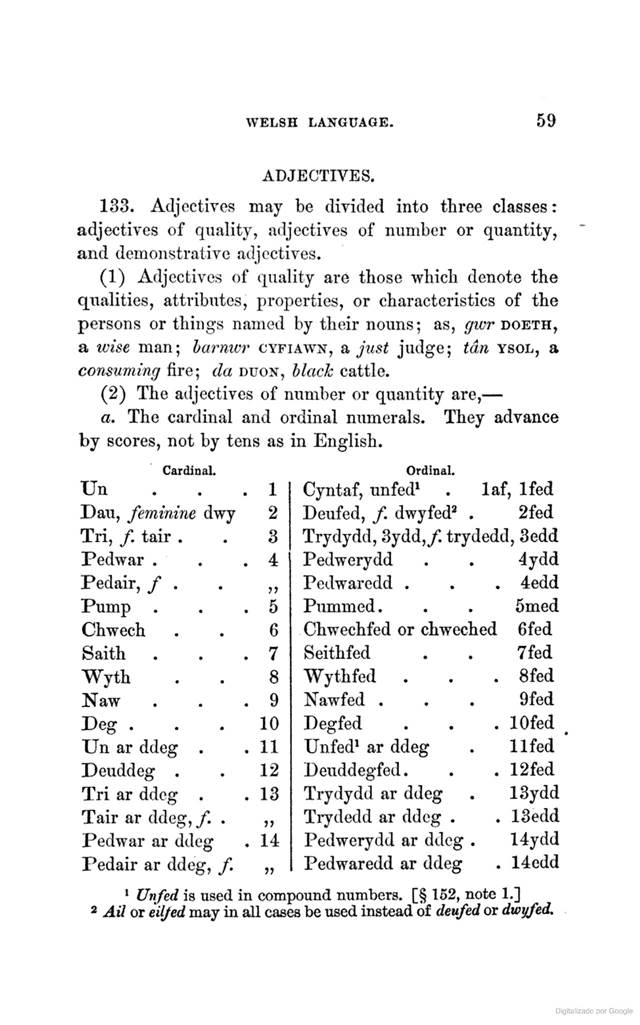

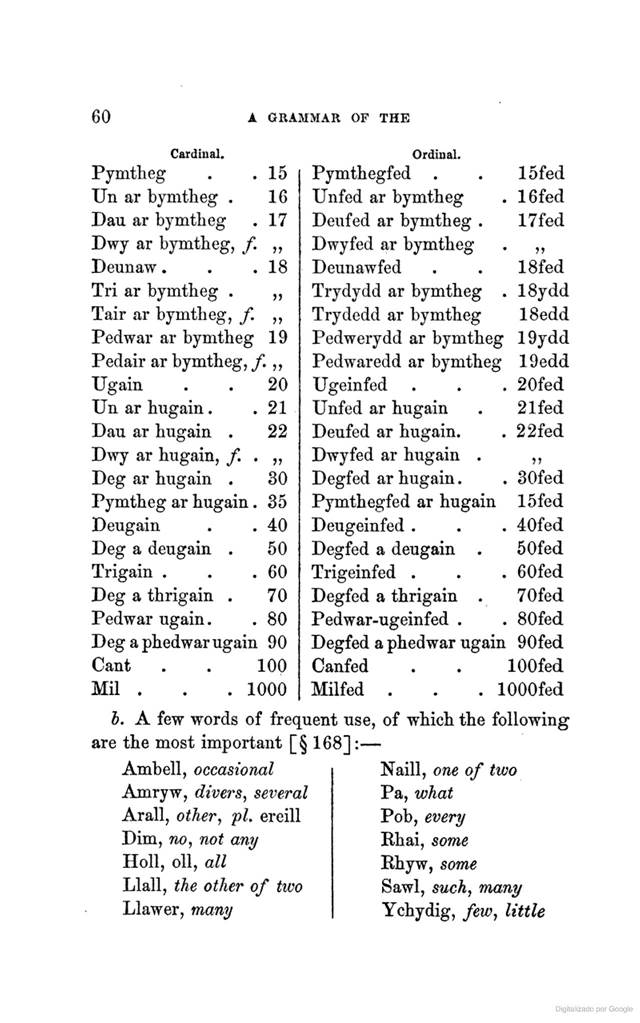

Adjectives ...... oV)

Adjectives of Quality .... 59

Adjectives of Number and Quantity . . . 59

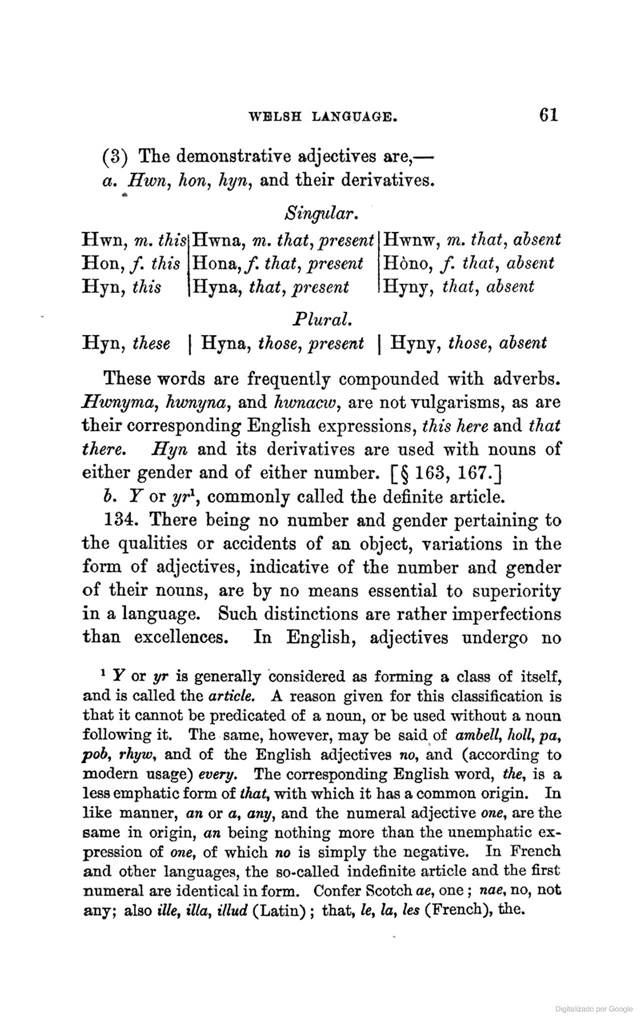

Demonstratives . . . . . 01

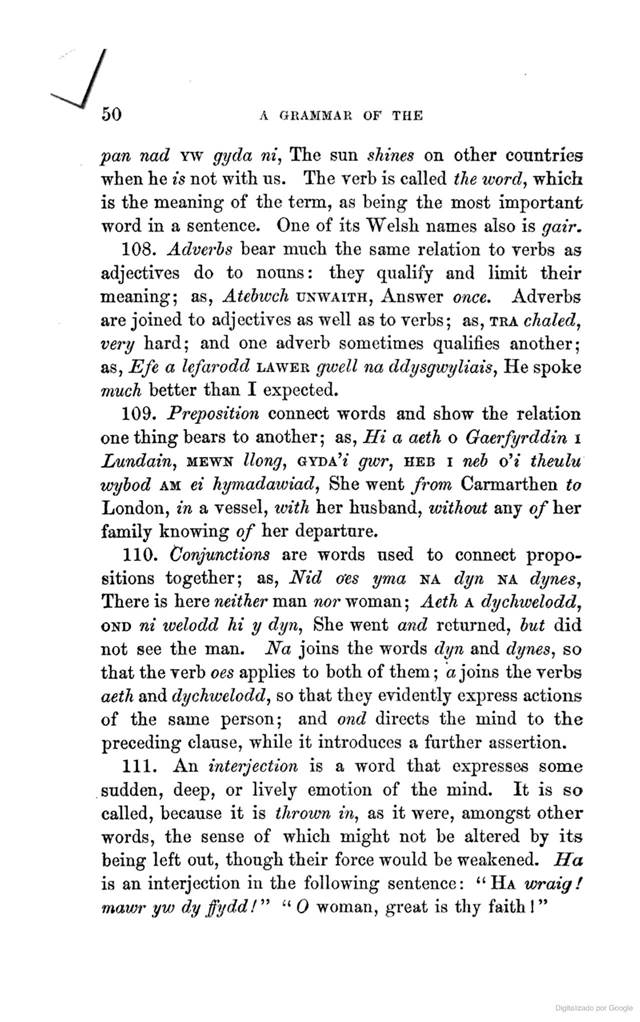

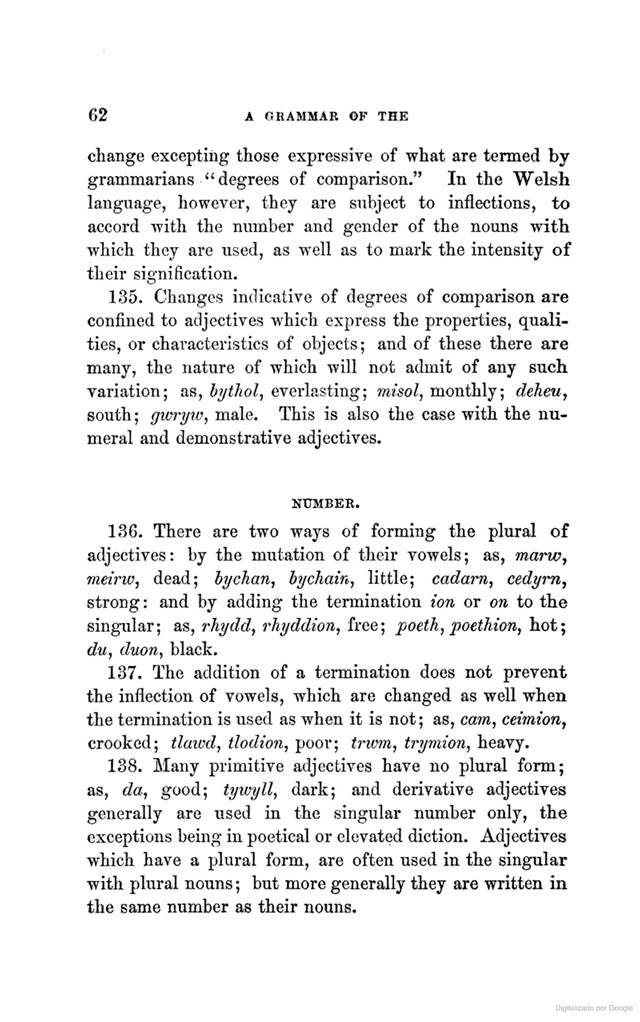

Number . . . . . . (\2

Gender ...... {')■]

Degrees of Comparison . . . . (14

Terminations of Adjectives . . . ()♦;

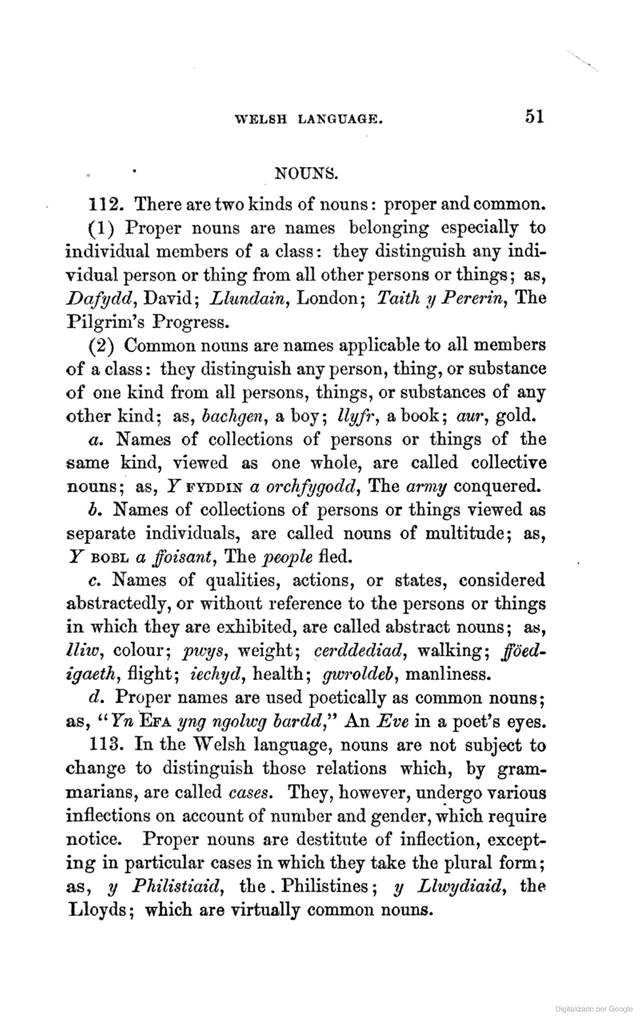

Pronouns . . . . . . . <;7

Personal Pronouns ..... (;?

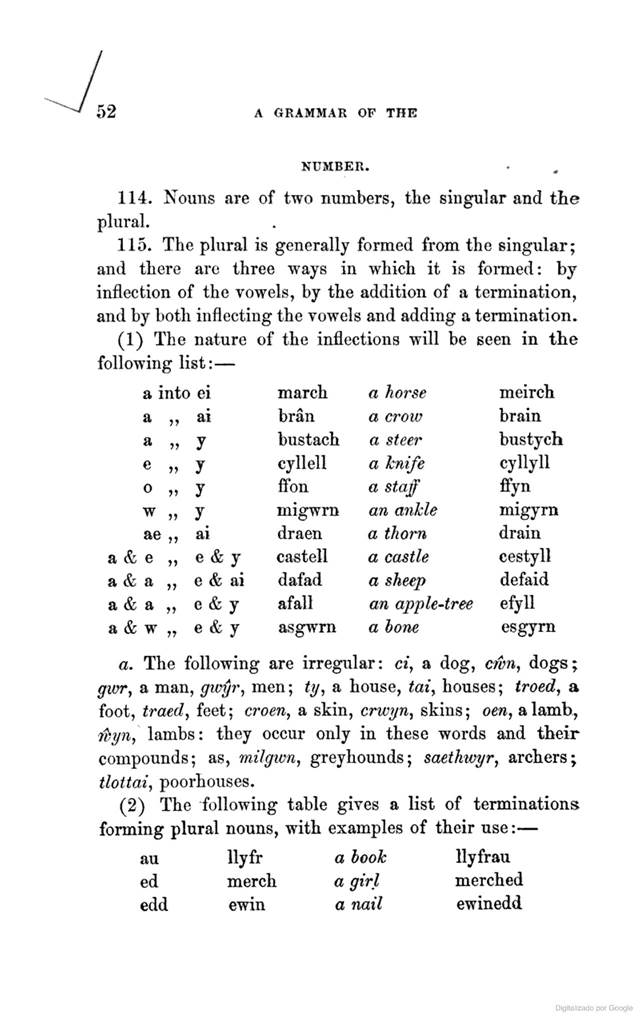

Relative Pronouns ..... 09

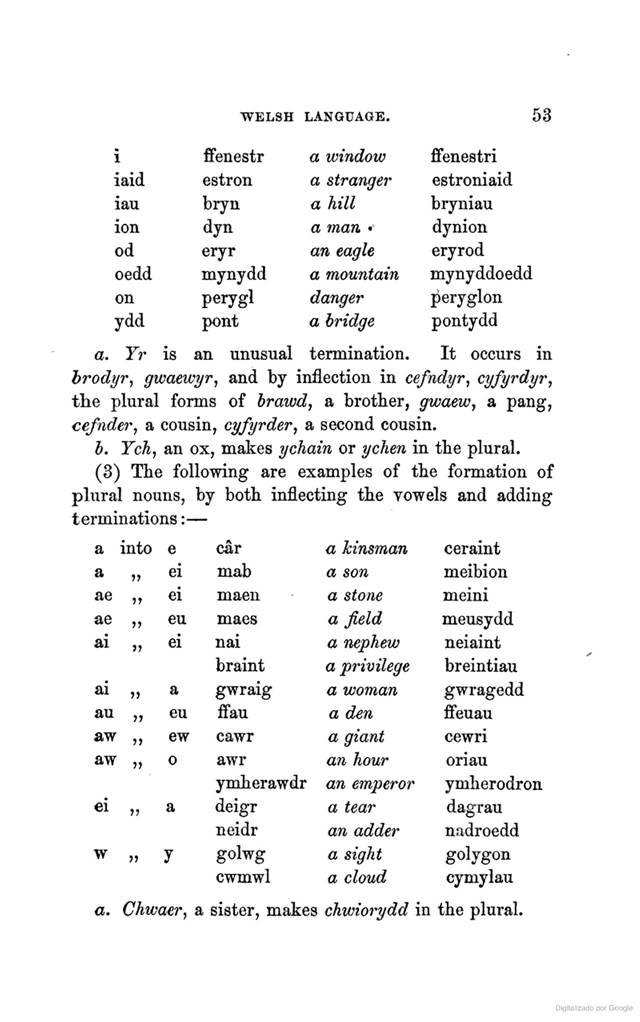

Other Pronominal Words and Phrases . . 72

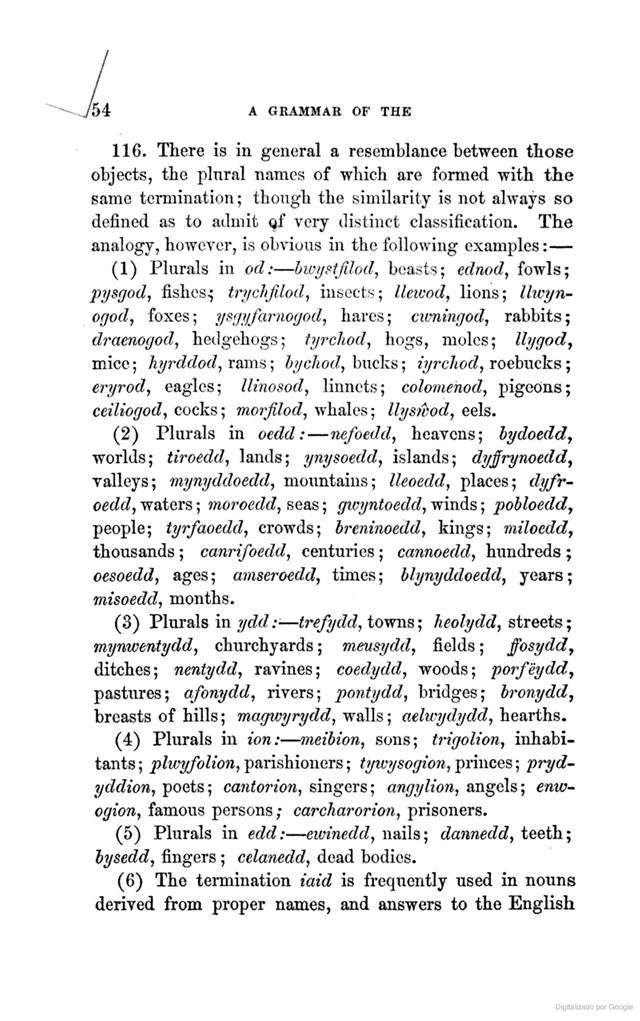

Verbs . . . . . . . 7.S

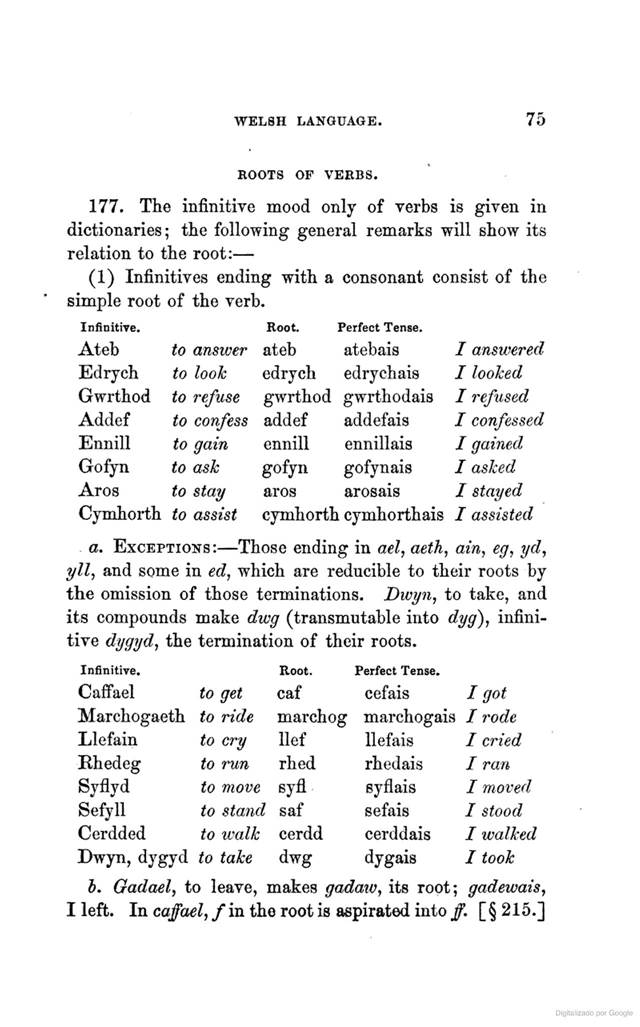

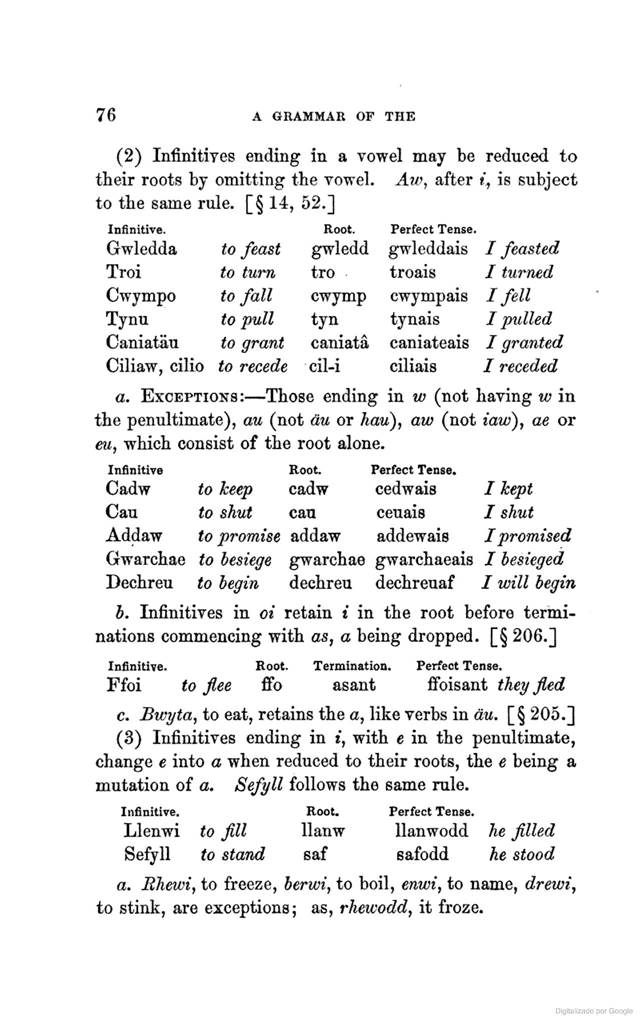

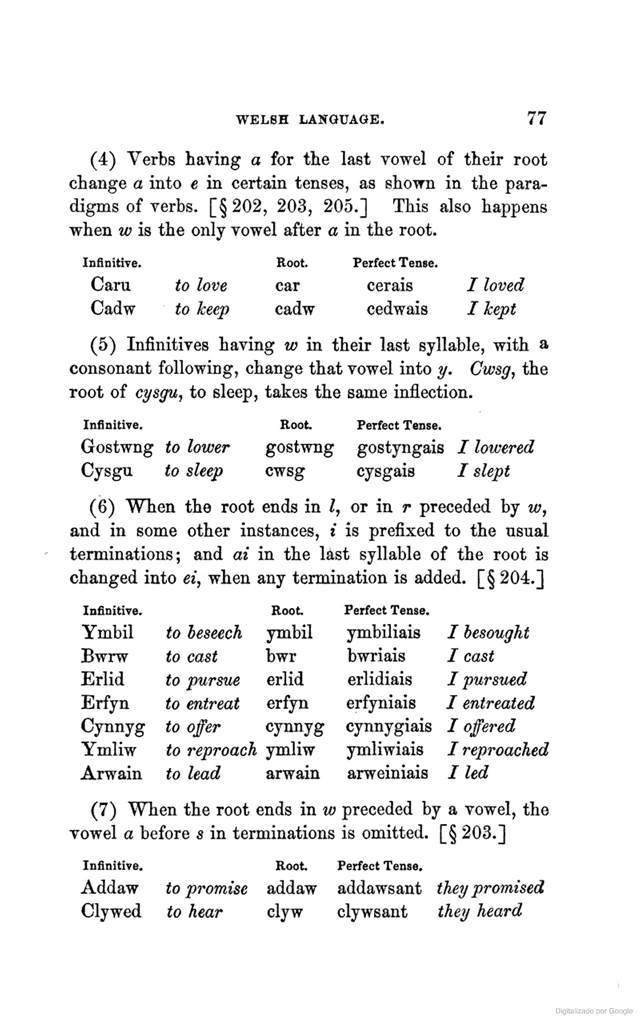

Roots of Verbs . . . . . 75

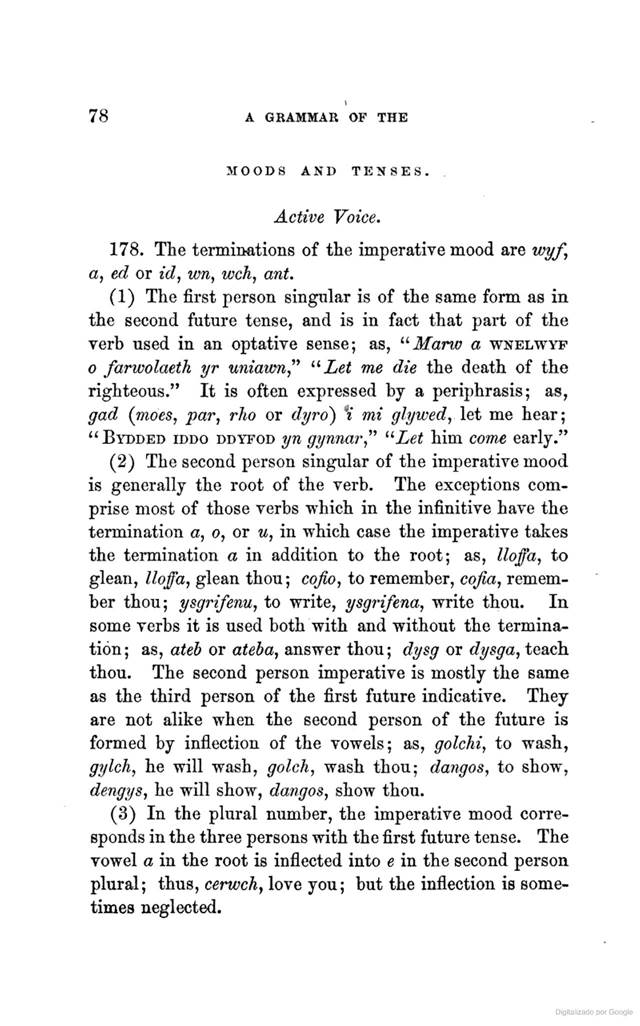

Moods and Tenses . . . , . 7S

Active Voice ..... 7S

Passive Voice . . . . . s:> %%

|

|

|

|

|

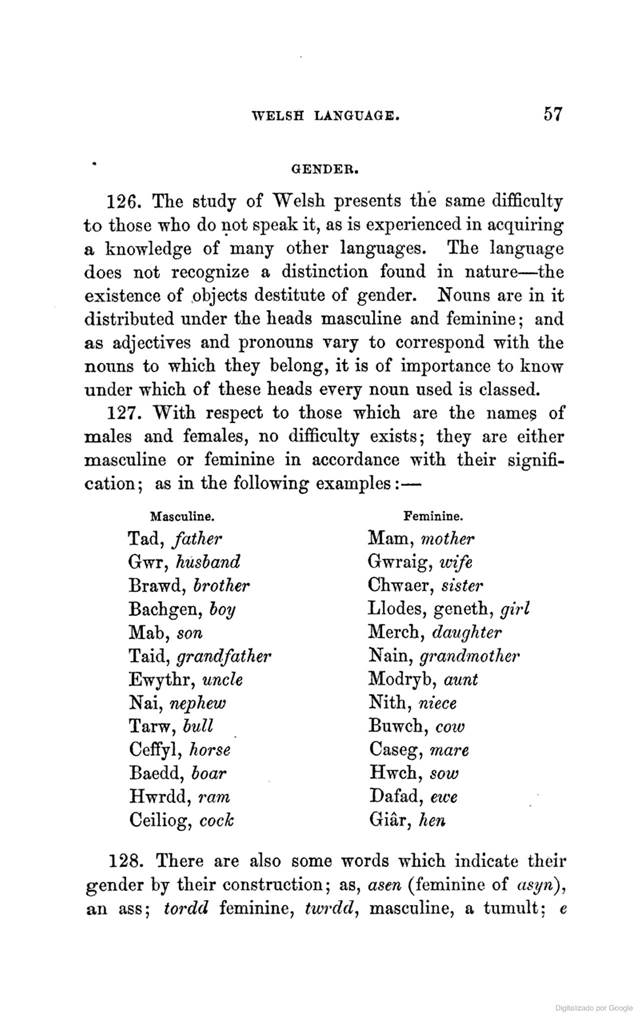

(delwedd B5511) 7 (delwedd B5511) 7

|

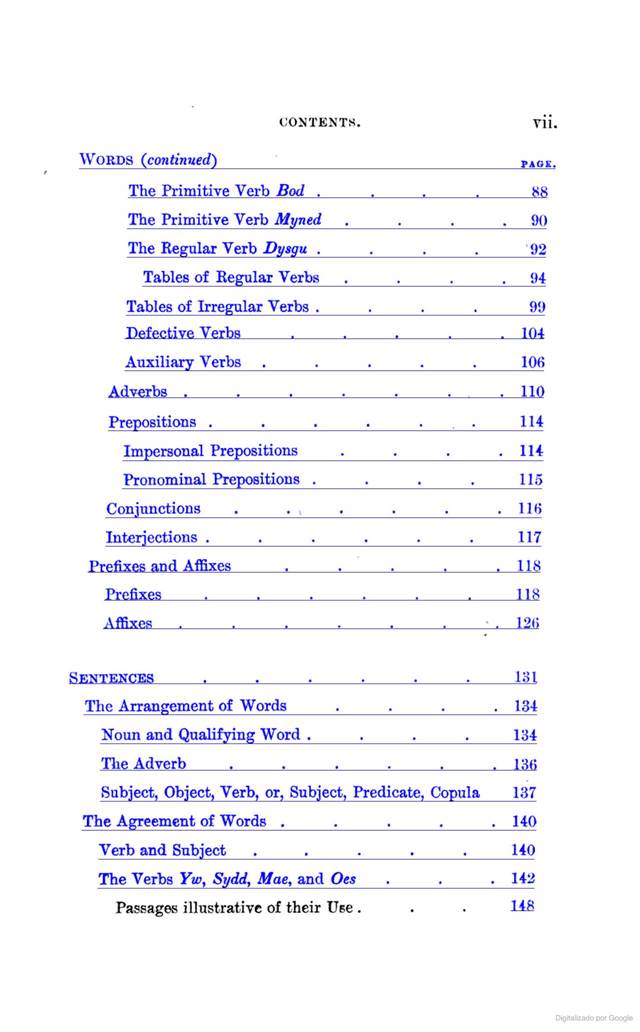

(.ON TENTH. VU. %%

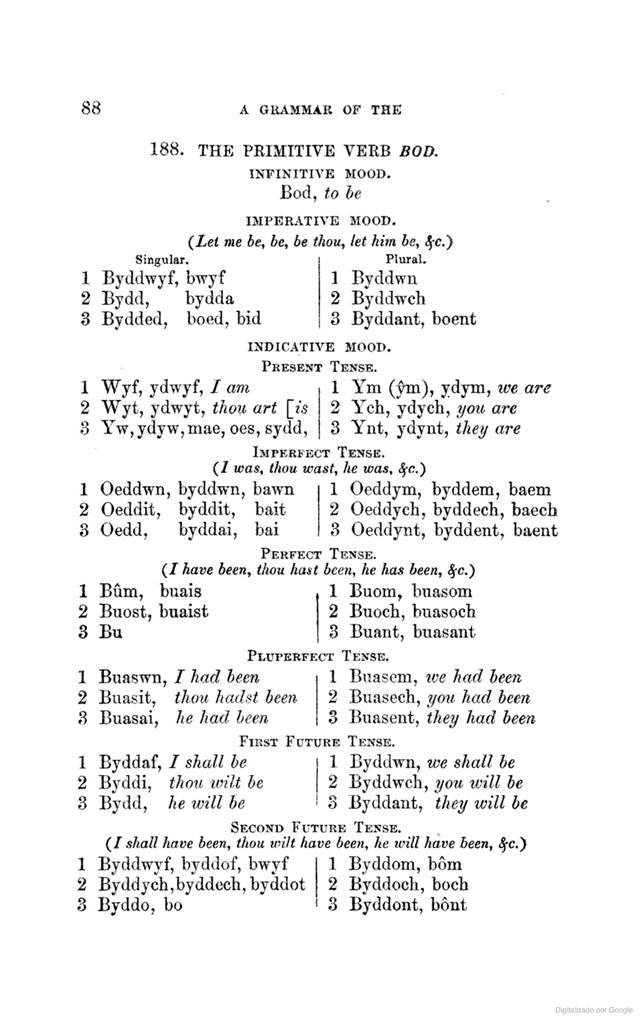

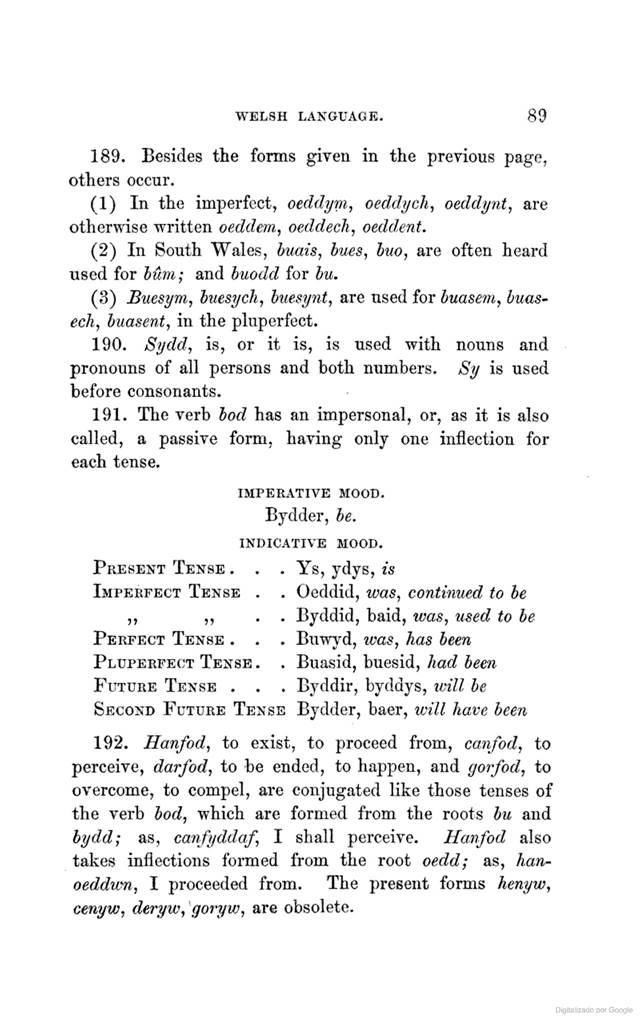

AN'oKDS (continued) %% fAQE. %% The Primitive Verb Bod .... 8«

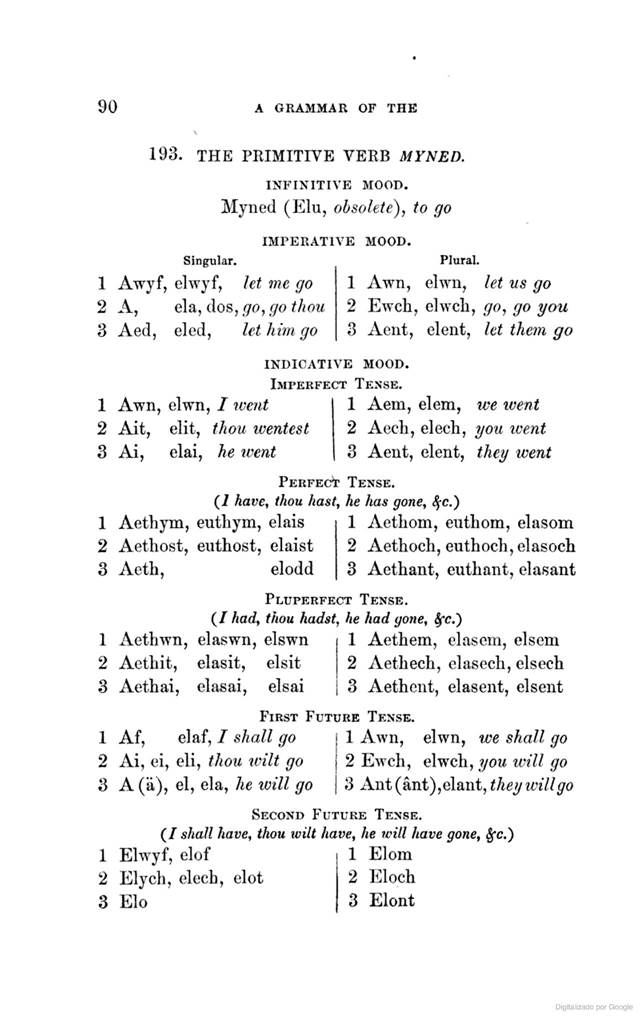

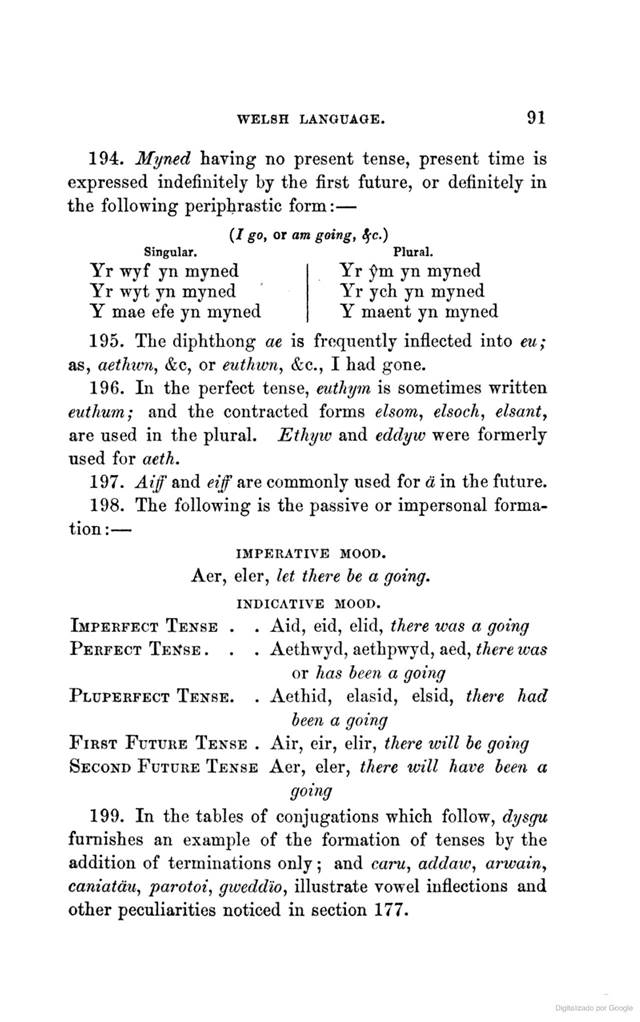

The Primitive Verb Myned . . ,90

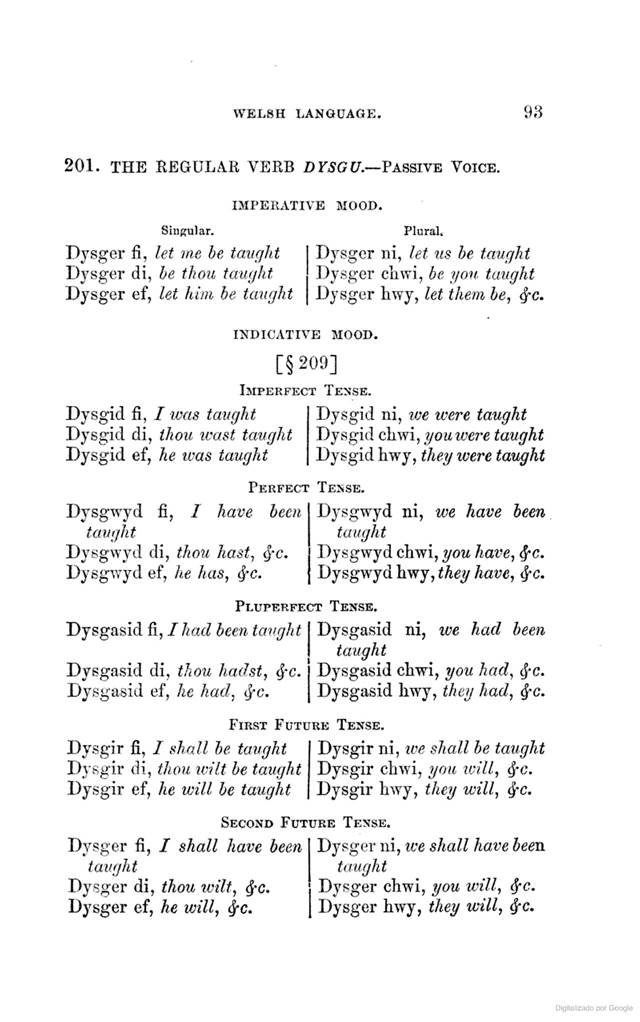

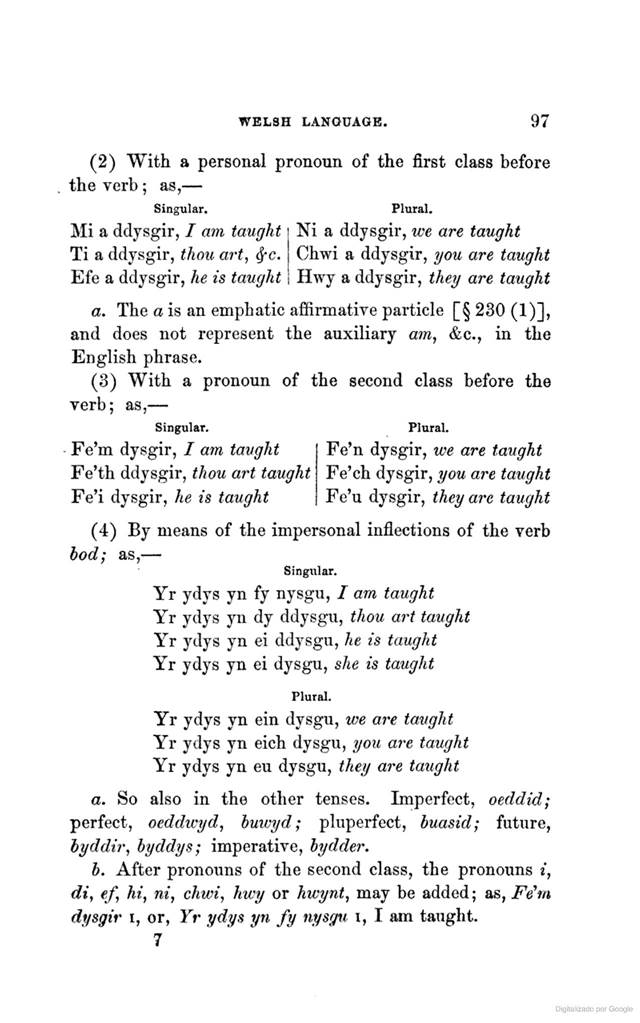

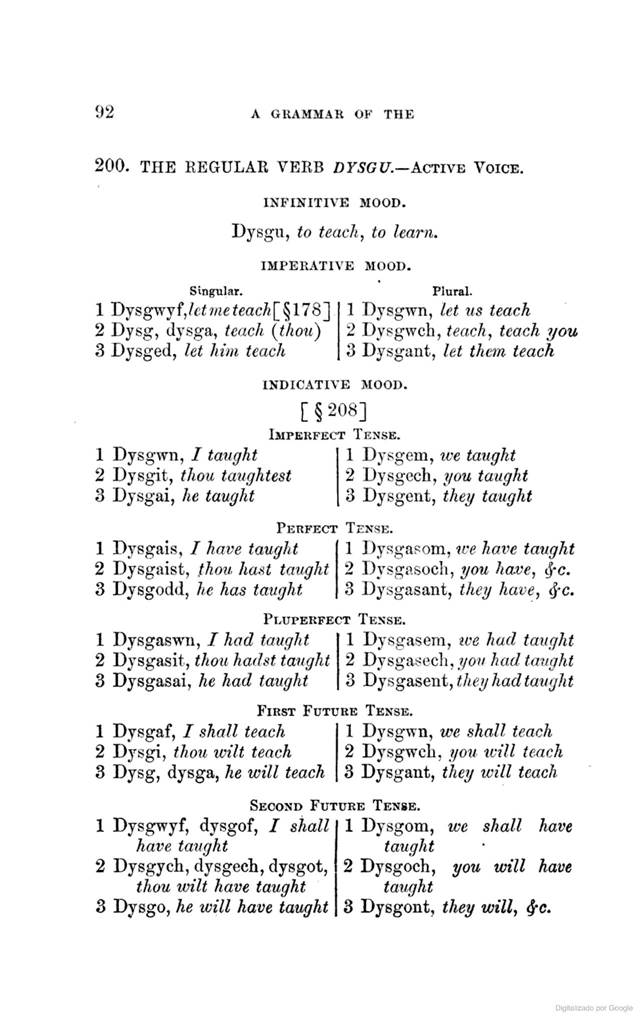

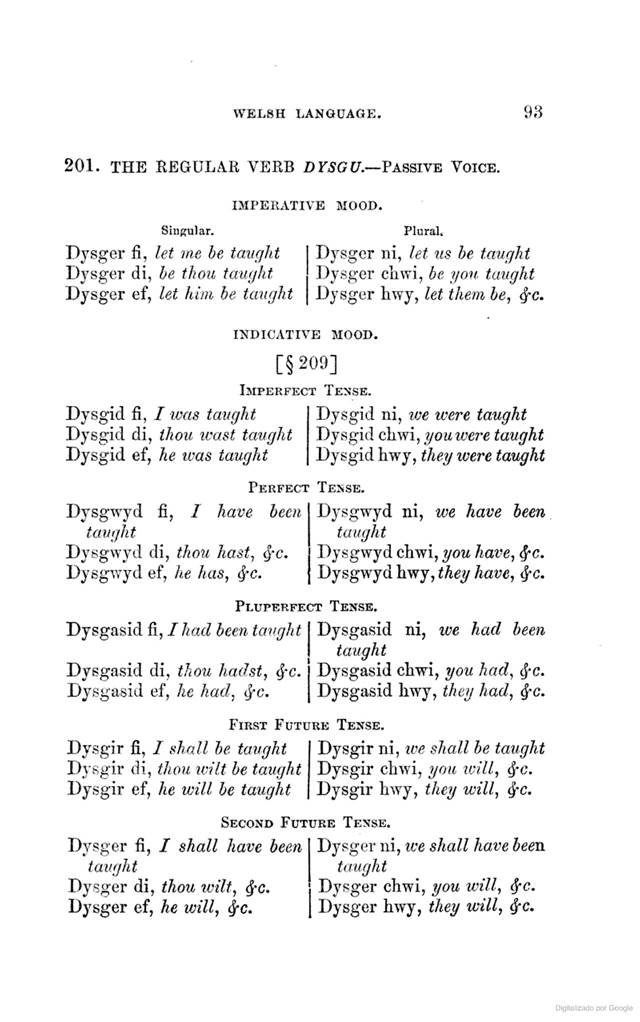

The Regular Verb Dysgu .... 92

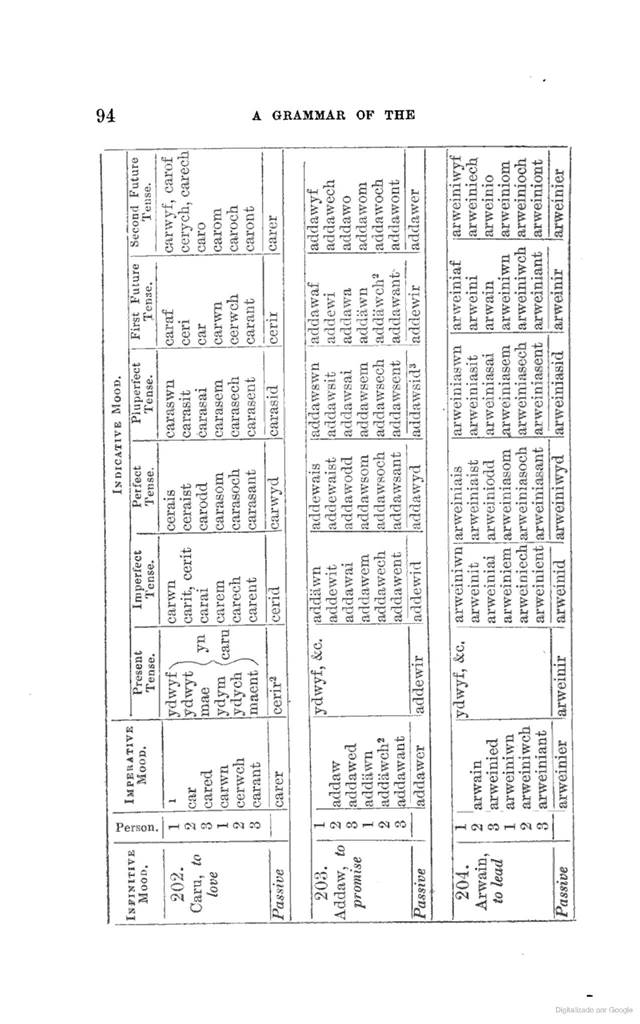

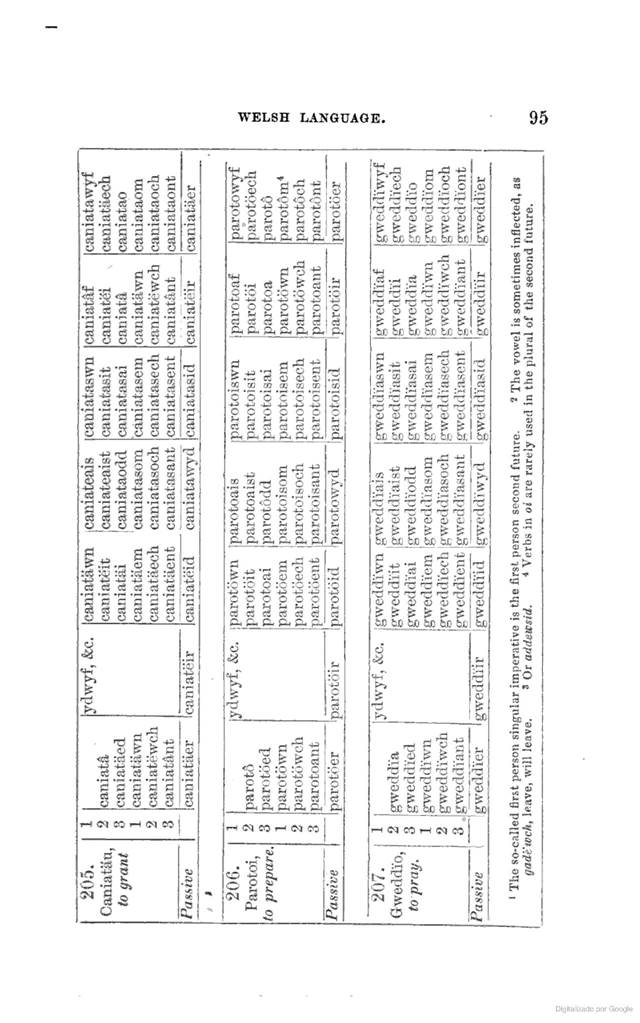

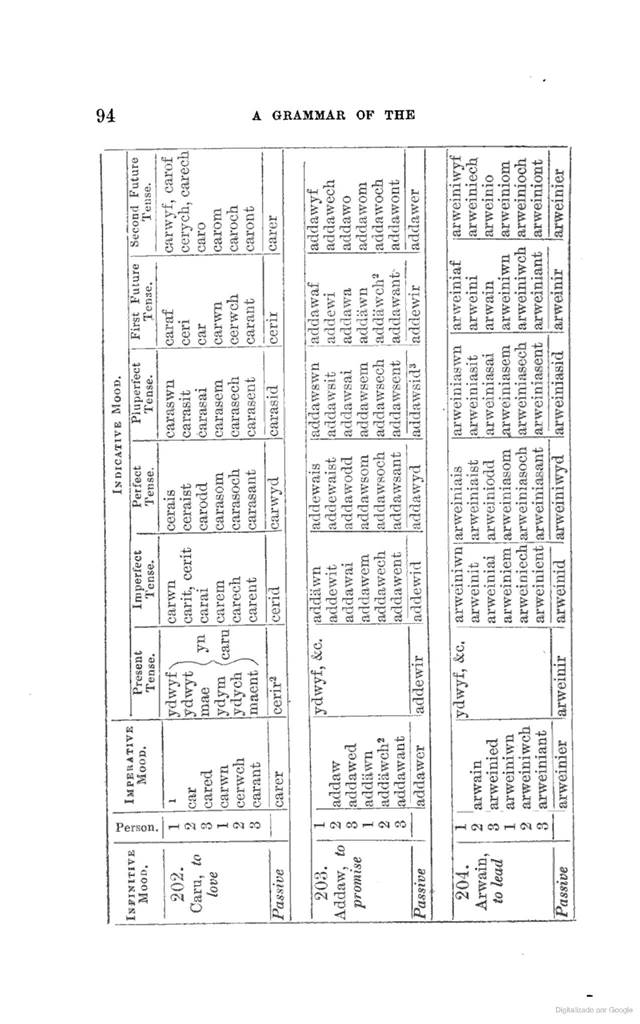

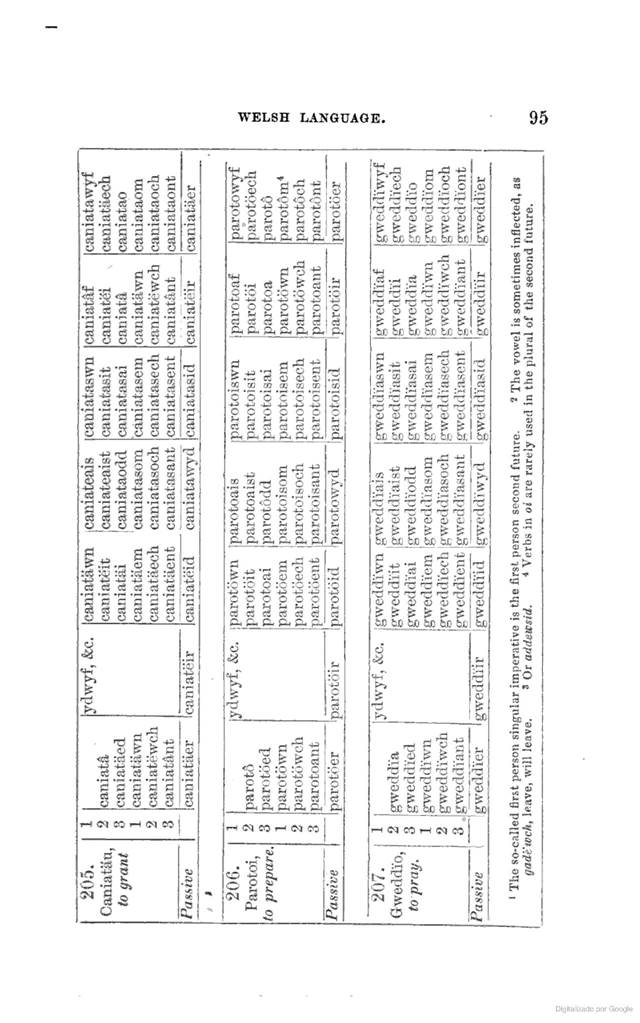

Tables of Regular Verbs . . . .94

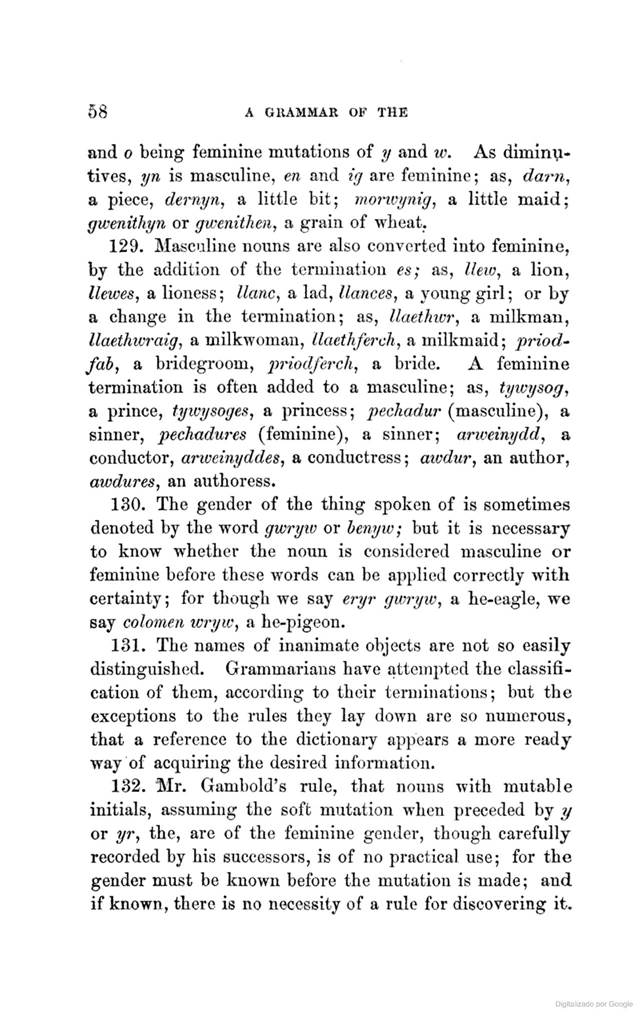

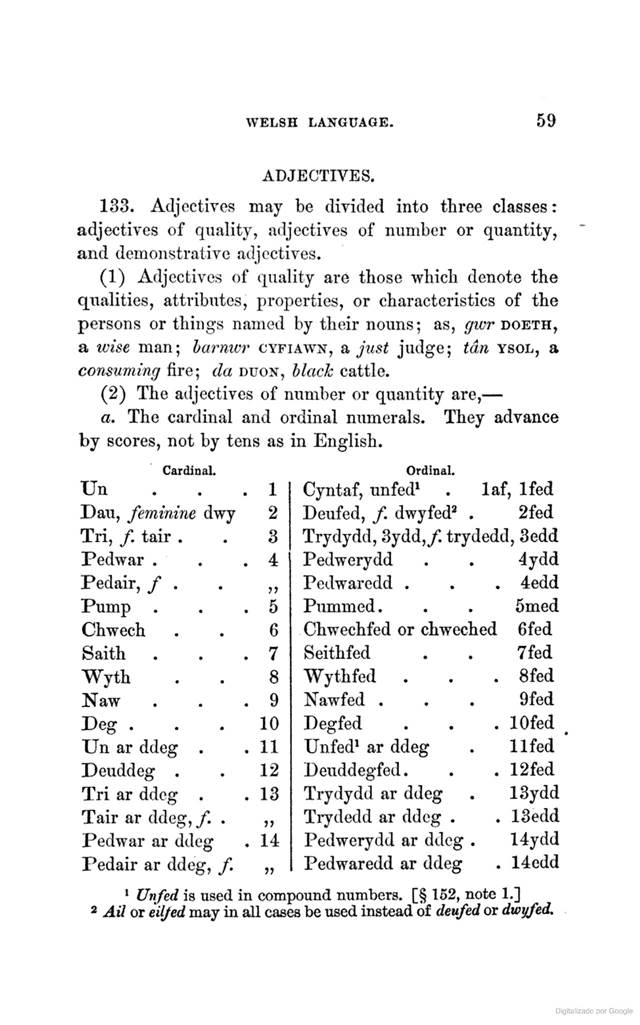

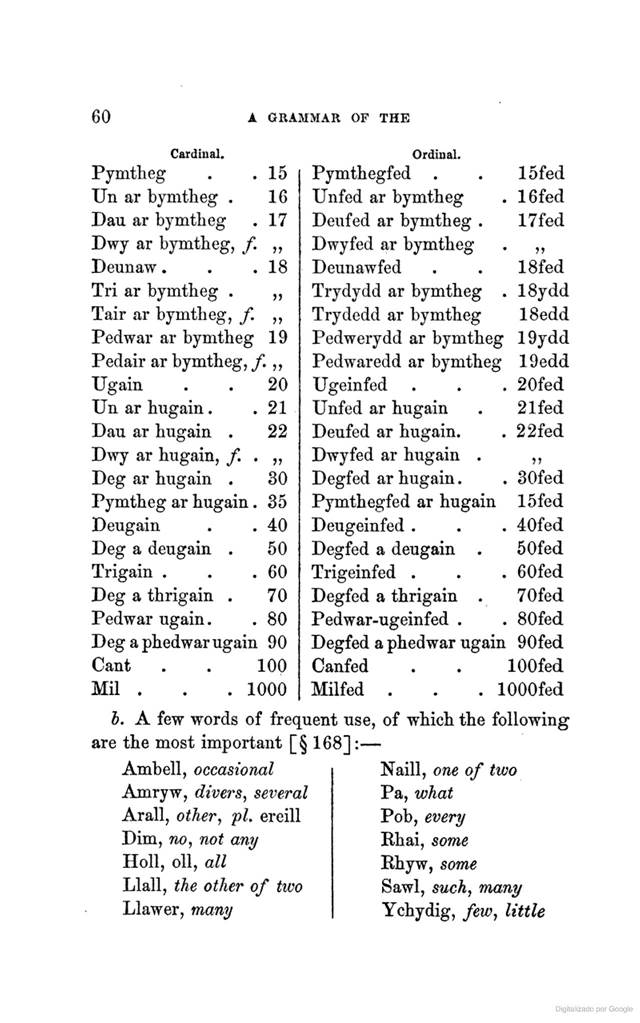

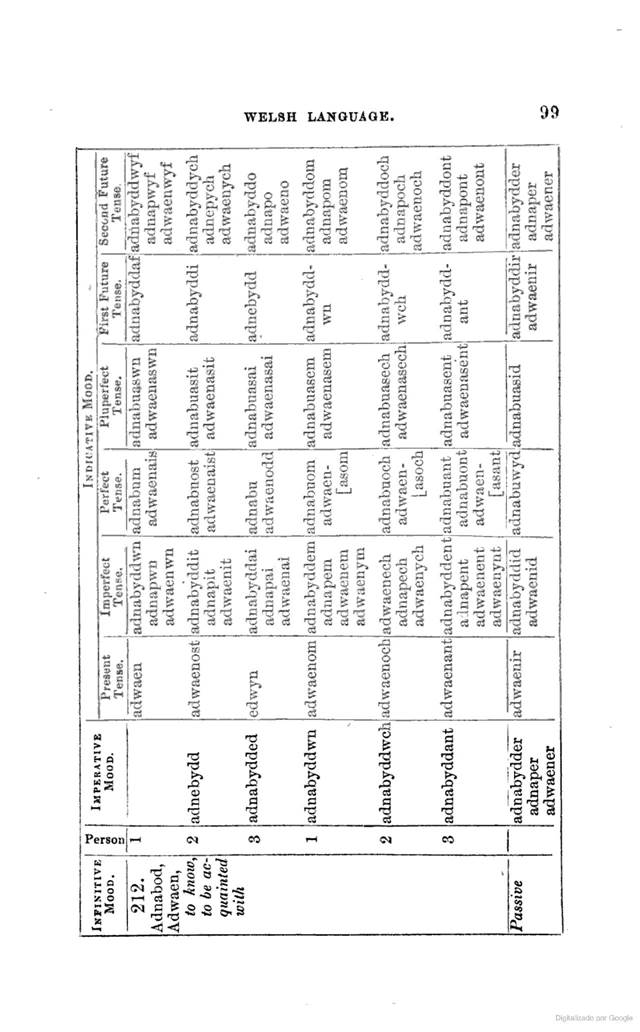

Tables of Irregular Verbs .... 99

Defective Verbs . . . . .104

Auxiliary Verbs ..... KKJ

Adverbs . . . . . . .110

Prepositions . . . . . . 114

Impersonal Prepositions . . . .114

Pronominal Prepositions . . . . 115

Conjunctions . . . . . .11(1

Interjections . . . . . . 117

Prefixes and Affixes . . . . .118

Prefixes . . . . . . lis

Affixes ....... 12«5

Sentences . . . . . . \'M

The Arrangement of Words . . . . 1;}4

Noun and Qualifying Word . . . . 1 ;U

The Adverb ...... VM\

Subject, Object, Verb, or, Subject. Predicate, Copula 137

The Agreement of Words . . . .140

Verb and Subject . . . . 140

The Verbs Yio” Sydd” Mae” and Oes . . . Wl

PantiagQA iJiiiritrativc of their \3;se . . • “'““ %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5512) 8 (delwedd B5512) 8

|

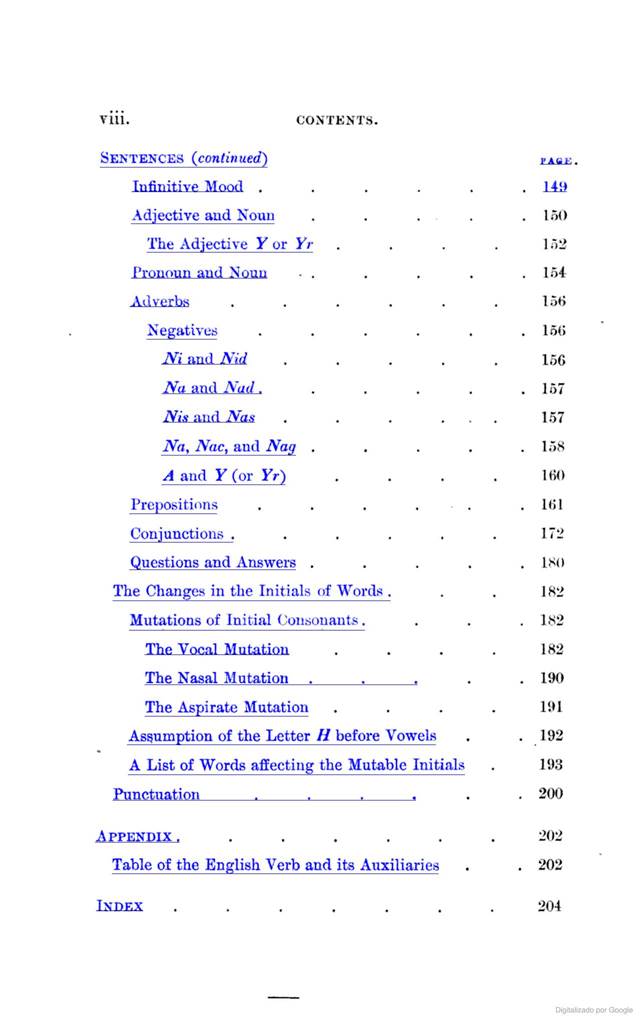

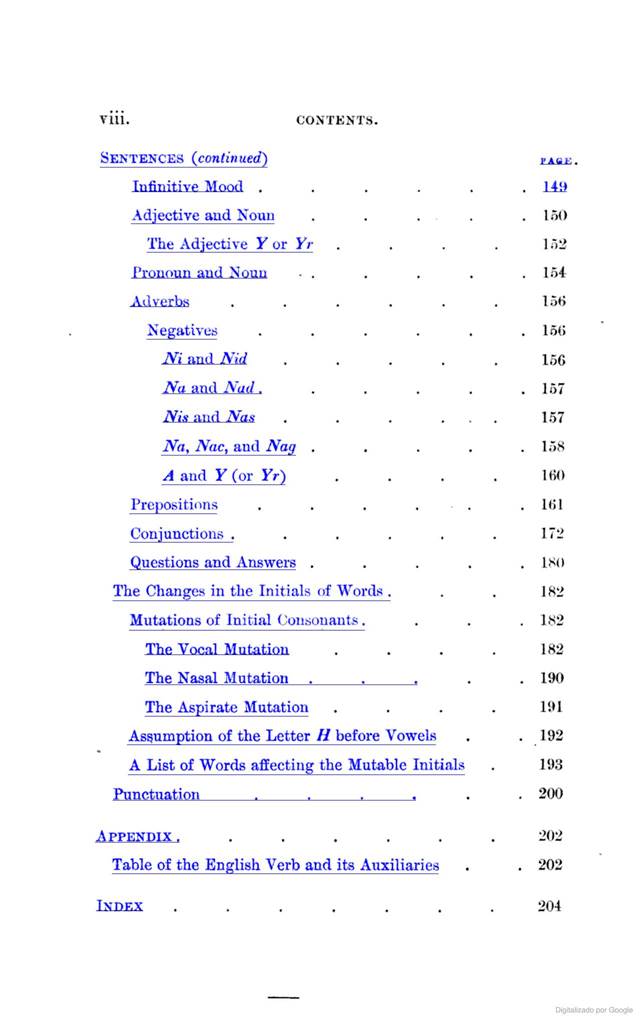

Till. %% CONTENTi.

%% Sentences “continued) %%PAGE %%Infinitive Mood ..... %%. 149 %%Adjective

and Nouu .... %%. 150 %%The Adjective F or Fr . %%152 %%Pronoun and Noun ....

%%. 154 %%Adverbs ...... %%156 %%Negatives ..... %%. 166 %%Ni and Nid .....

%%15G %%Na and Nad ..... %%. 157 %%Nis and Nas ..... %%157 %%Na, Nac, and Nag

.... %%. 158 %%A and Y (or Yr) .... %%160 %%Prepositions ..... %%. 161

%%Conjunctions ...... %%172 %%Questions and Answers .... %%. 180 %%The

Changes in the Initials of Words . %%182 %%Mutations of Initial Consonants .

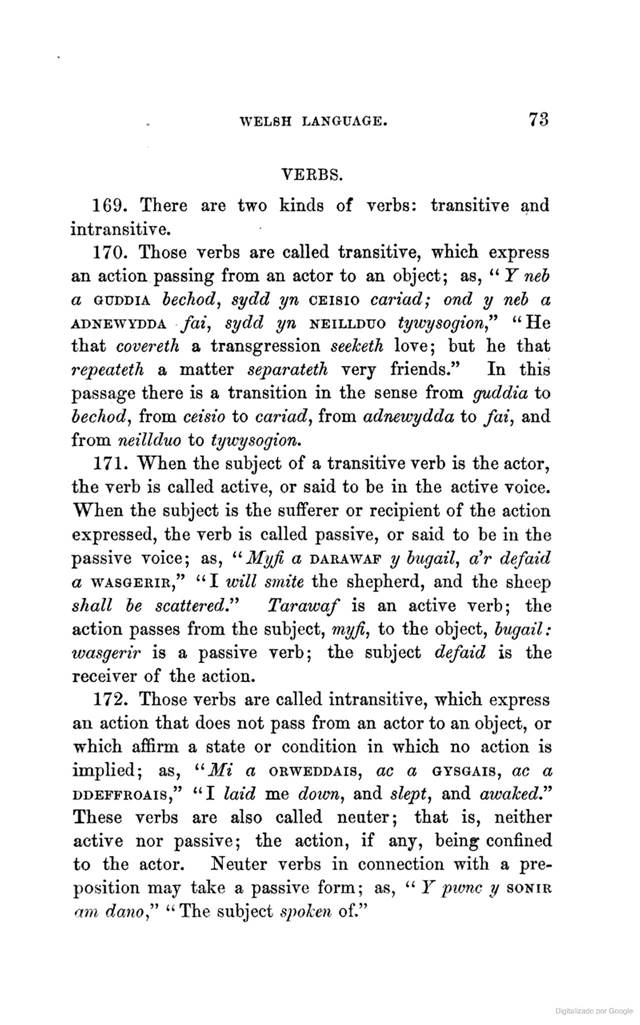

%%. 182 %%The Vocal Mutation .... %%182 %%The Nasal Mutation .... %%. 190

%%The Aspirate Mutation .... %%191 %%Assumption of the Letter H before Vowels

%%. 192 %%A List of Words aflEecting the Mutable Initials %%193 %%Punctuation

..... %%. 200 %%\.PPENDTX. ...... %%202 %%Table of the English Verb and its

Auxiliaries %%. 202 %% Zndex %% 'iVi\ %%

|

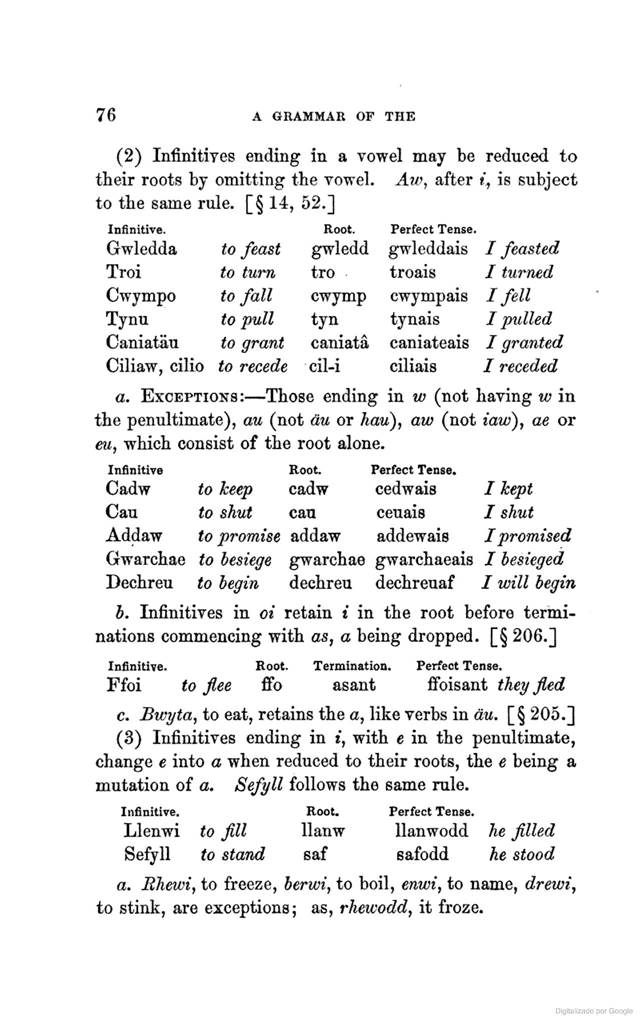

|

|

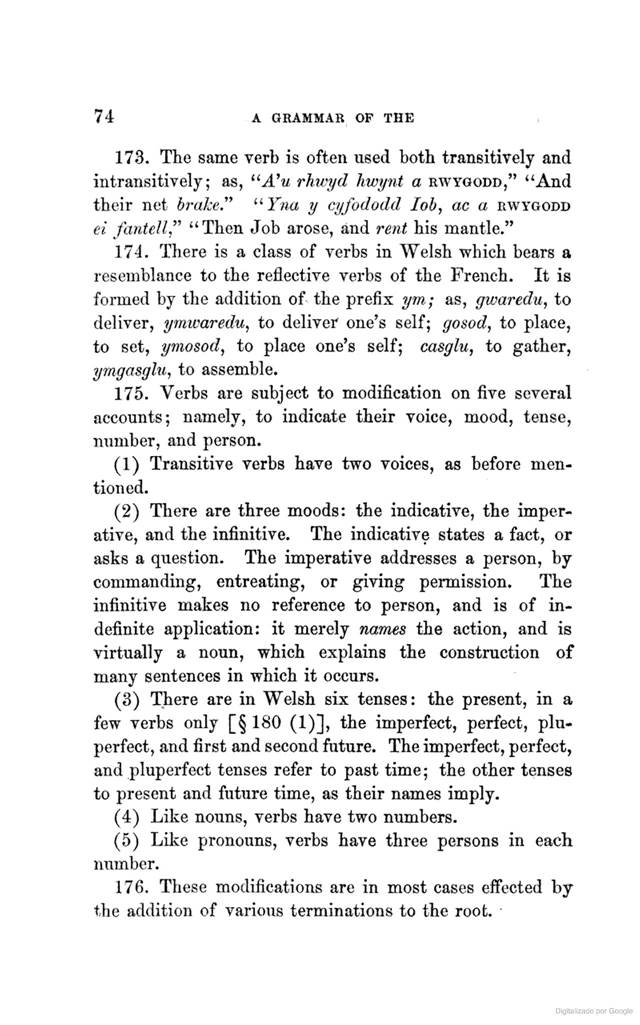

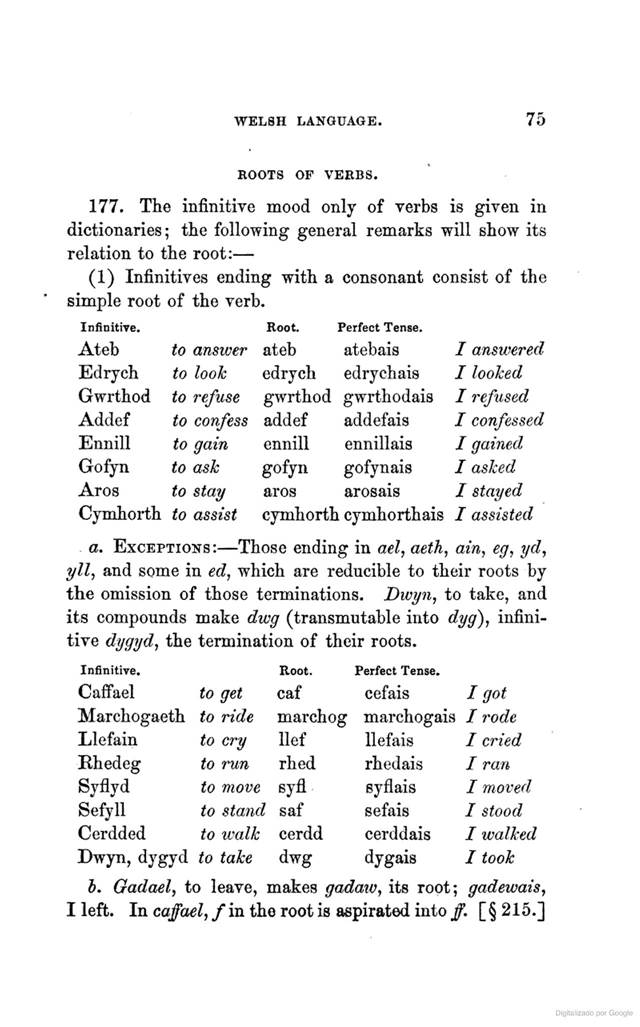

|

|

(delwedd B5513) (tudalen 001) (delwedd B5513) (tudalen 001)

|

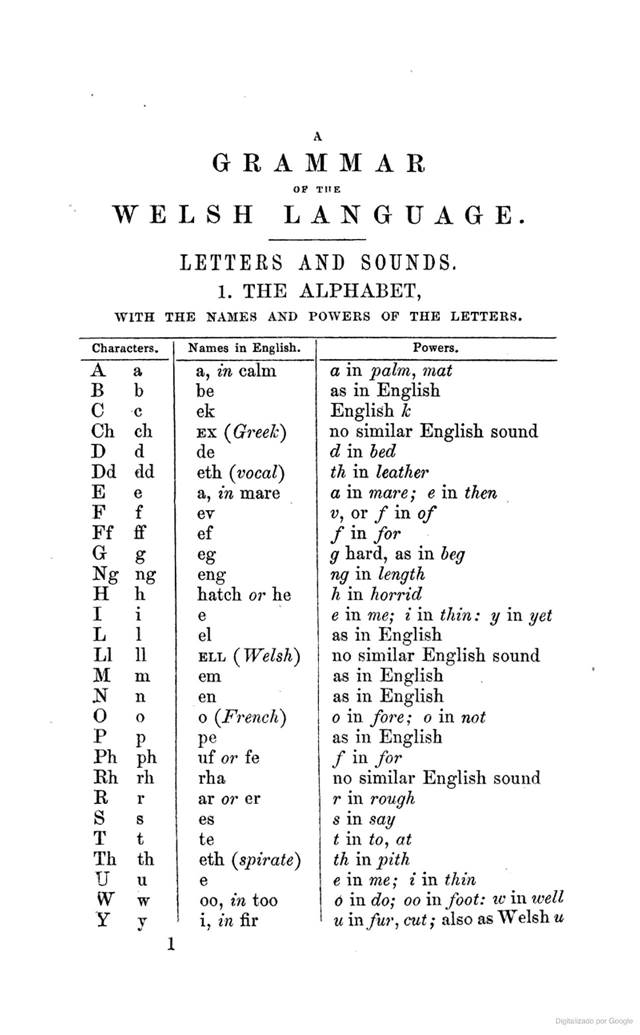

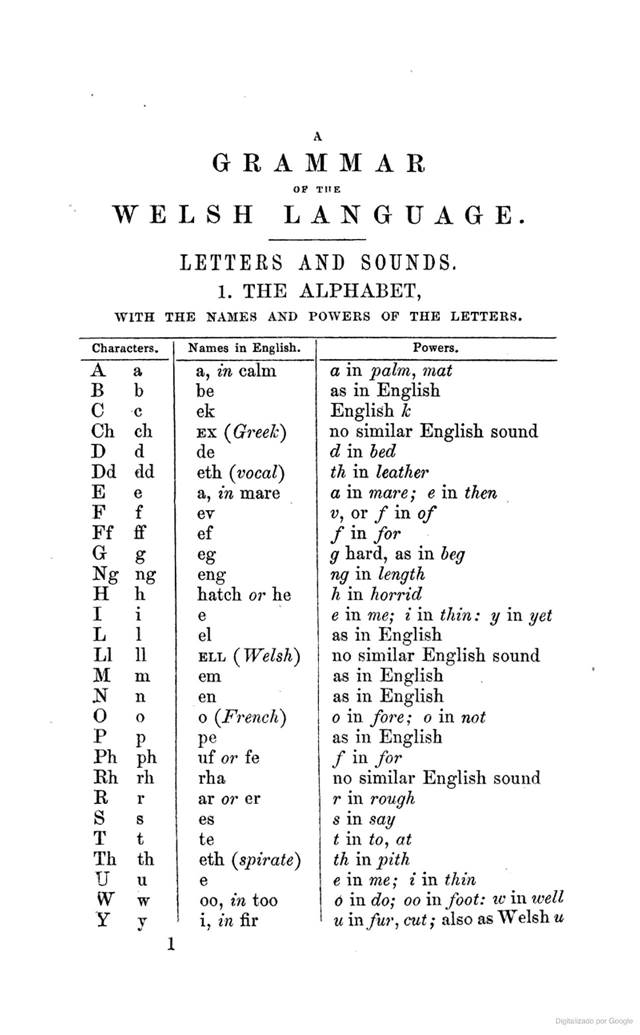

GRAMMAR %% OF TUB

%% WELSH LANGUAGE. %% LETTERS AND SOUNDS. 1. THE ALPHABET,

WITH THE NAMES AND FOWERS OF THE LETTERS. %% Characters. %%Names in English.

%%A %%a %%a, in calm %%B %%b %%be %%C %%c %%ek %%Ch %%ch %%Bx (Greek) %%D %%d

%%de %%Dd %%dd %%eth (vocal) %%E %%e %%a, in mare %%F %%f %%ev %%Ff %%ff %%ef

%%G %%g %%eg %%Ng %%T”g %%eng %%H %%h %%hatch or he %%I %%•

1 %%e %%L %%1 %%el %%LI %%u %%BLL (Welsh) %%M %%m %%em %%N %%n %%en

%%%%%%(French) %%P %%P %%pe %%Ph %%ph %%uf or fe %%Rh %%rh %%rha %%R %%r %%ar

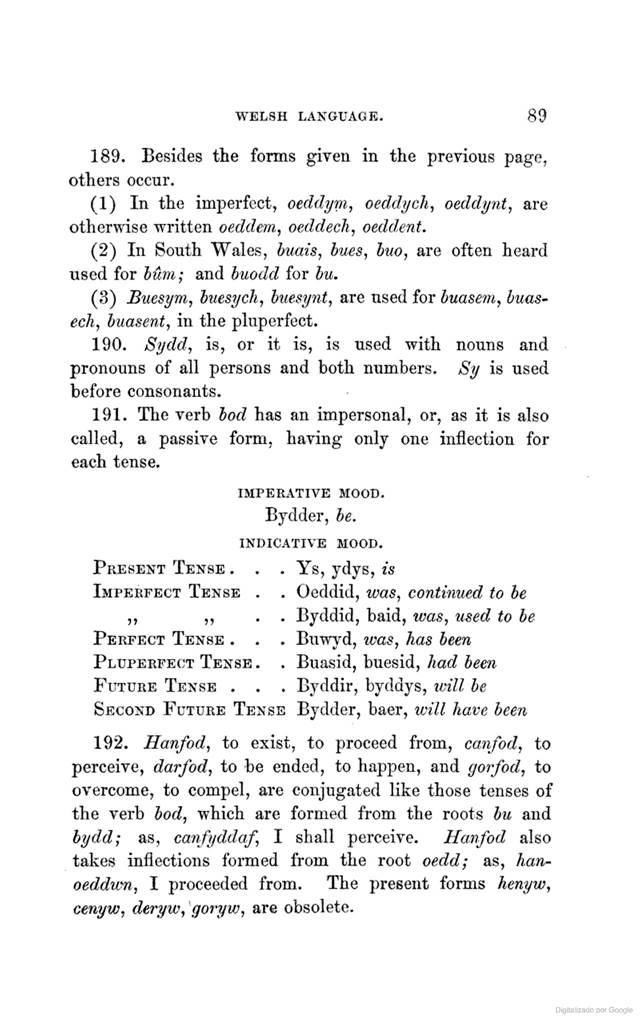

or er %%S %%s %%es %%T %%t %%te %%Th %%th %%eth (spirate) %%U %%u %%e %%W %%w

%%00, in too %%Y %%r ' %%1, m fir %% Powers. %% a in palm, mat

as in English

English k

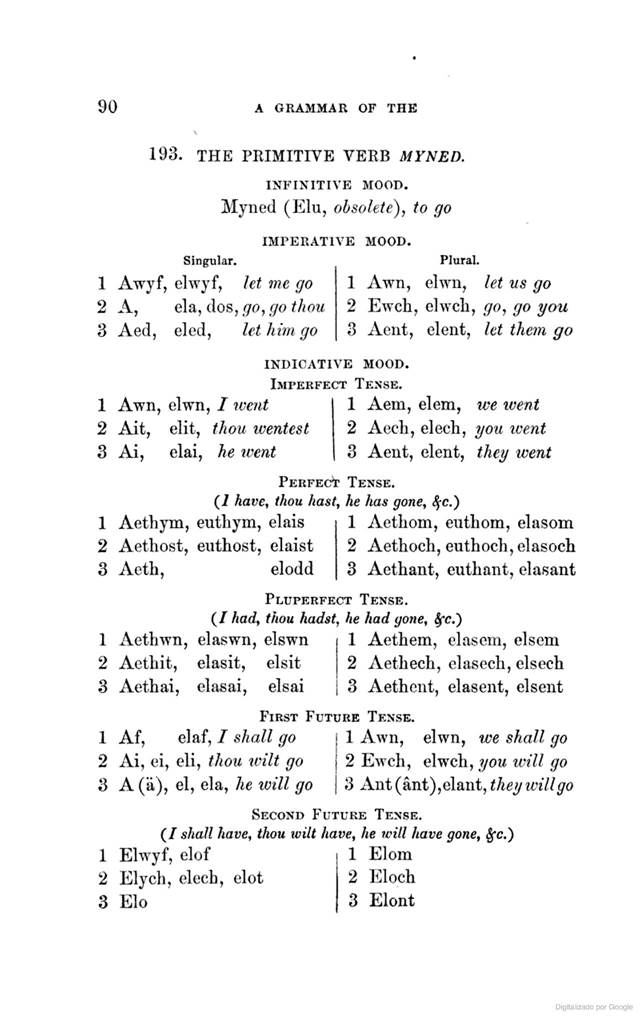

no similar English sound

d in bed

th in leather

a in mare; e in then

V, or / in of

fin for

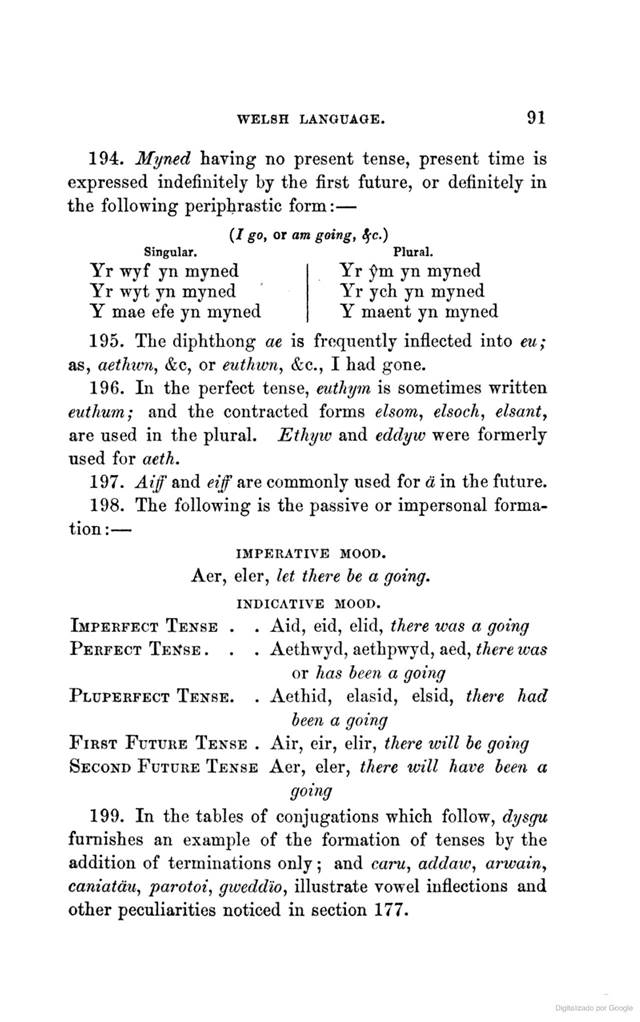

g hard, as in beg

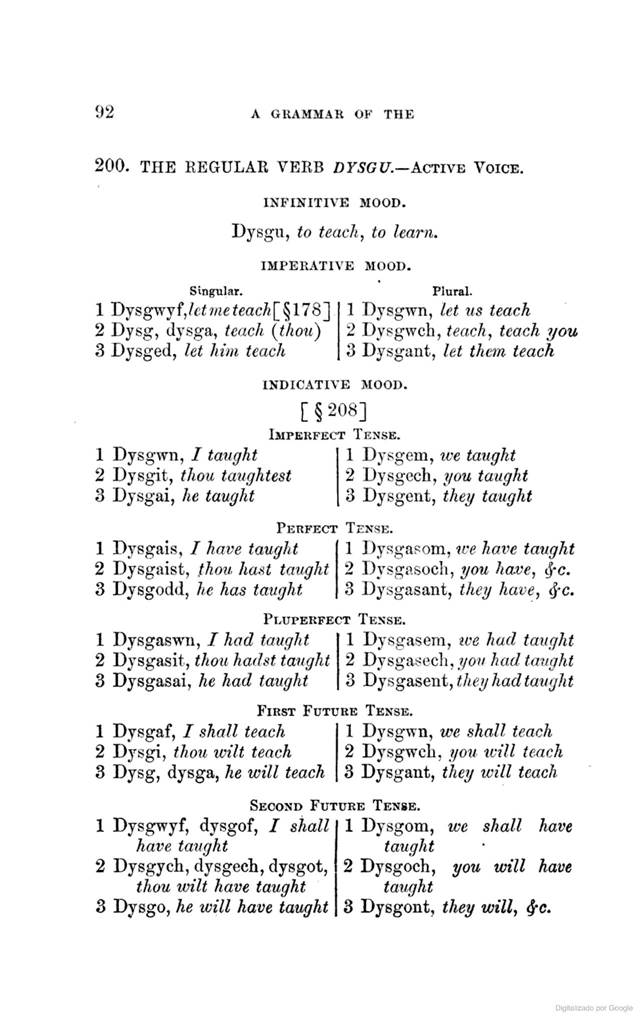

ng in length

h in horrid

e in me; i in thin: y in yet

as in English

no similar English sound

as in English

as in English

in fore; o in not

as in English

/ in /or

no similar English sound

r in rough

8 in say

t in to, at

th in pith

e in me; i in thin

in do; com Joot: 'vjo\s:L\»eX\.

u in far, cut ; «\!b.o “i” ““>». %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5514) (tudalen 002) (delwedd B5514) (tudalen 002)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE %%

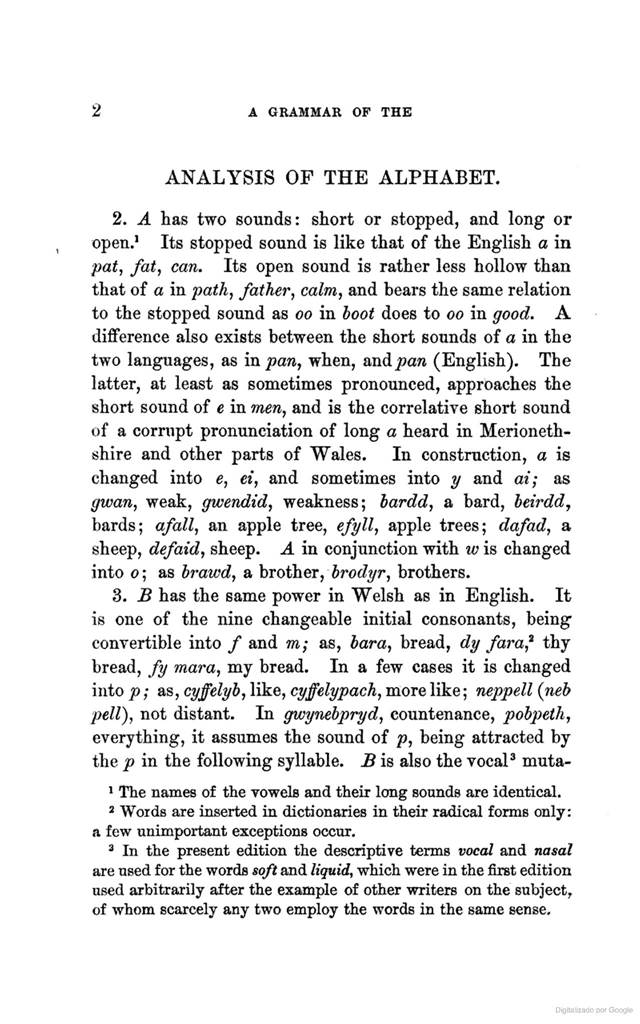

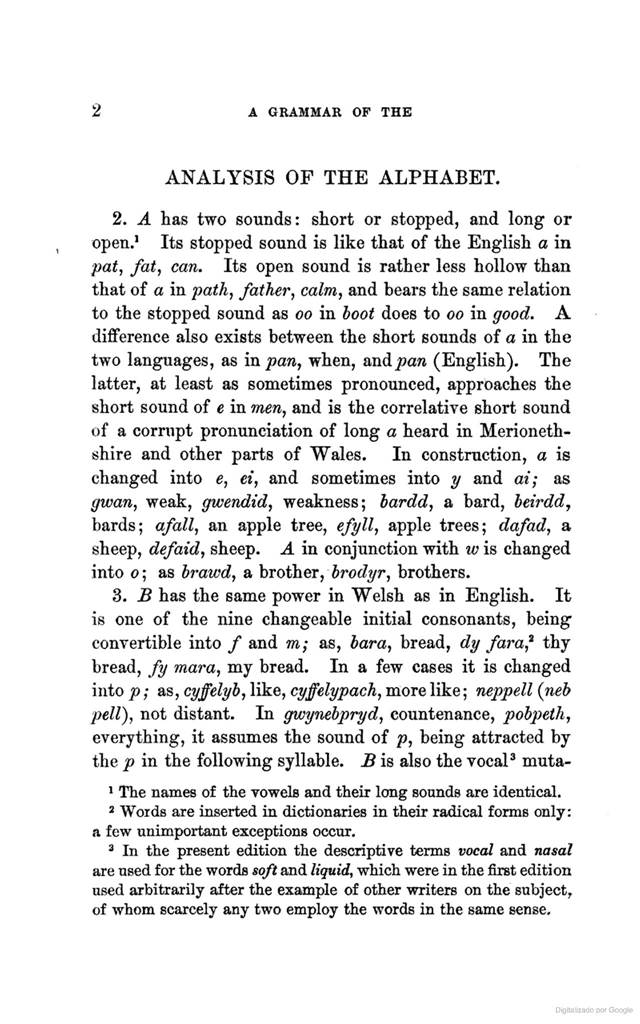

ANALYSIS OF THE ALPHABET.

2. A has two sounds: short or stopped, and long or open.' Its stopped sound

is like that of the English a in pat, fat, can. Its open sound is rather less

hollow than that of a in path, father, calm, and bears the same relation to

the stopped sound as oo in hoot does to oo in good. A difference also exists

between the short sounds of a in the two languages, as in pa/n, when, and

joaw (English). The latter, at least as sometimes pronounced, approaches the

short sound of e in men, and is the correlative short sound of a corrupt

pronunciation of long a heard in Merioneth- shire and other parts of Wales.

In construction, a is changed into e, ei, and sometimes into y and at; as

gwan, weak, gwendid, weakness; hardd, a bard, heirdd, bards; afall, an apple

tree, efyll, apple trees; dafad, a sheep, defaid, sheep. A in conjunction

with w is changed into ; as hrawd, a brother, hrodyr, brothers.

3. B has the same power in Welsh as in English. It is one of the nine

changeable initial consonants, being convertible into / and m; as, bar a,

bread, dy fara” thy bread, fy mara, my bread. In a few cases it is changed

into “; as, cyffelyh, like, cyffelypach, more like ; neppell (neb pell), not

distant. In gwynebpryd, countenance, pobpeth, everything, it assumes the

sound of p, being attracted by the p in the following syllable. B is also the

vocaP muta-

* The names of the vowels and their long sounds are identical.

> Words are inserted in dictionaries in their radical forms only: a few

unimportant exceptions occur.

' In the present edition the descriptive terms vocal and nasal are used for

the words soft and liquid, which were in the first edition used Arbitrarily

after the example of other writers on the subject, of whom scarcely any two

employ the woiAb m l\ve «>«avfe ““w&e. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5515) (tudalen 003) (delwedd B5515) (tudalen 003)

|

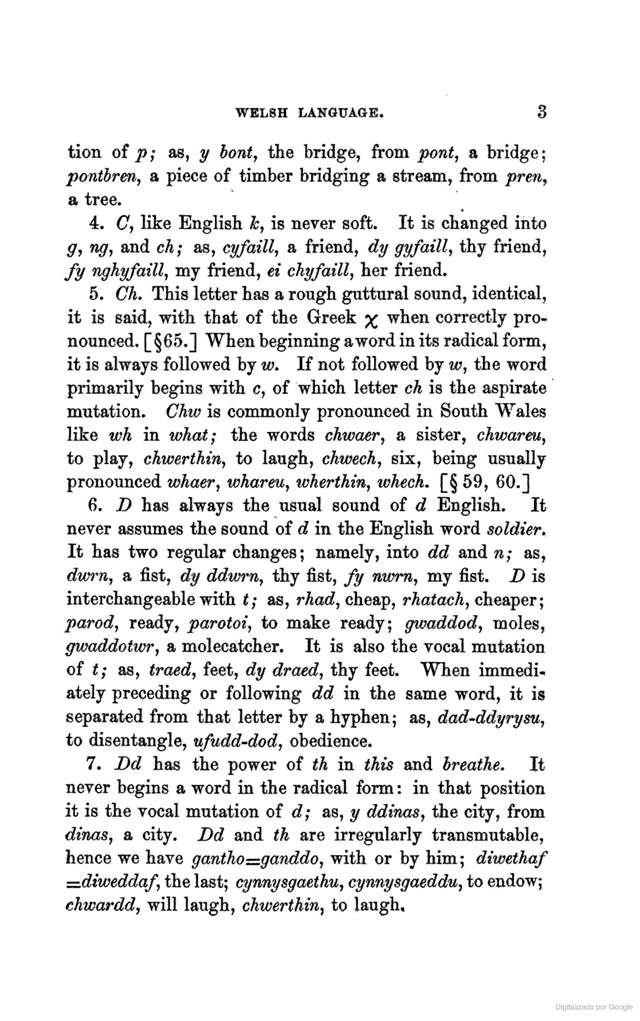

WELSH LANGUAGE. 3

tion of p; as, y bont, the bridge, from pont, a bridge; pontbren, a piece of

timber bridging a stream, from prm, a tree.

4. C, like English h, is never soft. It is changed into g, ngj and ch; as,

cyfaill, a friend, dy gyfaill, thy friend, ft/ nghyfaill” my friend, ei

chyfaill, her friend.

5. Ch, This letter has a rough guttural sound, identical, it is said, with

that of the Greek p” when correctly pro* nonnced. [§65.] When beginning a

word in its radical form, it is always followed by w. If not followed by «?,

the word primarily begins with c, of which letter ch is the aspirate

mutation. Chw is commonly pronounced in South Wales like wh in what; the

words chwaer, a sister, chwareu, to play, chwerthin, to laugh, chweck, six,

being usually pronounced whaer, whareu” wherthin, whech, [§59, 60,]

6. D has always the usual sound of d English. It never assumes the sound of d

in the English word soldier. It has two regular changes; namely, into dd and

n; as, dwm” a fist, dy ddimm, thy fist, fy mum, my fist. D is interchangeable

with t; as, rkad, cheap, rhatach, cheaper; parodj ready, parotot, to make

ready; gwaddod, moles, gwaddotwTj a molecatcher. It is also the vocal

mutation of “; as, traed, feet, dy draed, thy feet. When immedi- ately

preceding or following dd in the same word, it is separated from that letter

by a hyphen; as, dad'“ddyrysu, to disentangle, ufudd-dod, obedience,

7. Dd has the power of th in this and breathe. It never begins a word in the

radical form : in that position it is the vocal mutation of d; as, y ddinas,

the city, from dmaSj a city. Dd and th are irregularly transmutable, hence we

have gantho”ganddo, with or by him; diwethaf “.diweddaf, the last;

cynnysgaethu” ci/Tini|8gaeddu”\» “\i”i3”\ chwardd, will laugh, chwerthin” to

\a\igk. %% 4

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5516) (tudalen 004) (delwedd B5516) (tudalen 004)

|

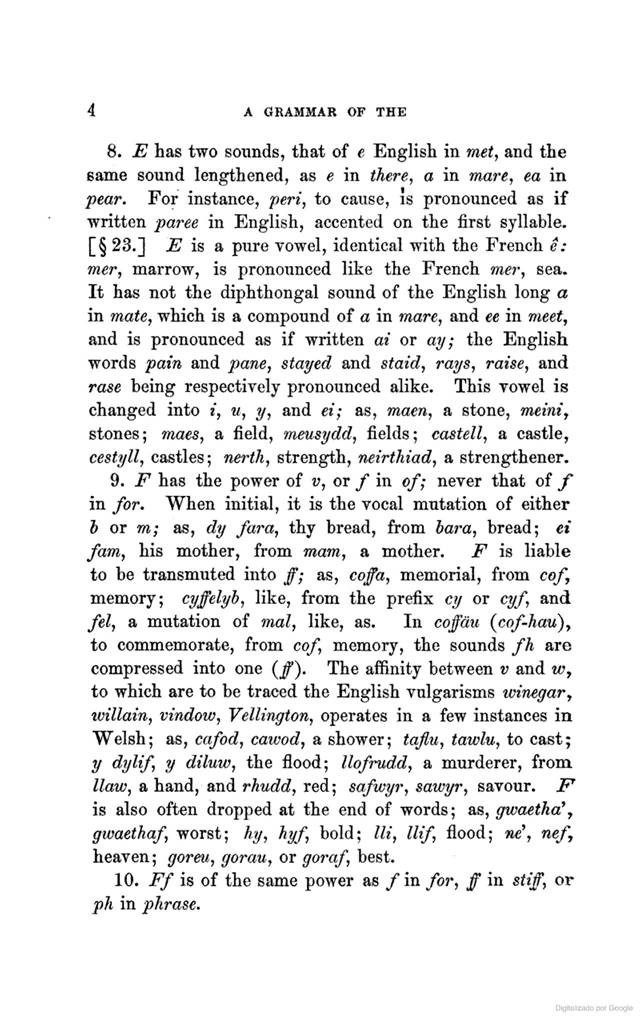

A GRAMMAR OF THE

8. E has. two sounds, that of e English in metj and the same sound

lengthened, as e in there, a in mare, ea in peq”. For instance, peri, to

cause, is pronounced as if written paree in English, accented on the first

syllable. [§ 23.] “ is a pure vowel, identical with the French e: mer,

marrow, is pronounced like the French mer, sea. It has not the diphthongal

sound of the English long a in mate, which is a compound of a in mare, and ee

in meet, and is pronounced as if written ai or ay; the English words pain and

pane, stayed and staid, rays, raise, and rase being respectively pronounced

alike. This vowel is changed into i, u, y, and ei; as, maen, a stone, meiniy

stones; maes, a field, meusydd, fields; castell, a castle, cestyll, castles;

nerth, strength, neirthiad, a strengthener.

9. F has the power of v, or / in of; never that of / in for. When initial, it

is the vocal mutation of either h or m; as, dy far a, thy bread, from hara,

bread; ei fam, his mother, from mam, a mother. F is liable to be transmuted

into ff; as, coffa, memorial, from cof memory; cyffelyh, like, from the

prefix cy or cyf, and fel, a mutation of mal, like, as. In coffdu (cof-hau),

to commemorate, from cof, memory, the sounds fh are compressed into one (/).

The affinity between v and w, to which are to be traced the English

vulgarisms winegar, tvillain, vindow, Vellington, operates in a few instances

in "Welsh; as, cafod, cawod, a shower; tafiu, tawlu, to cast; y dylif, y

diluw, the flood; llofrudd, a murderer, from Haw, a hand, and rhudd, red ; safwyr,

sawyr, savour. F is also often dropped at the end of words; as, gwaetha\

gwaetkaf, worst; hy, hyf bold; Hi, llif, flood; ne\ nef heaven; goreu, gorau,

or goraf, best.

10. Ff is of the same power as / in for, ff in stiff, or j”A in p Arose, %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5517)(tudalen 005) (delwedd B5517)(tudalen 005)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 5

11. G” is always pronounced like g in beg and get. Like ch [§ 5], it has an

affinity for tlie labial w [\ 60], being when radical often followed by that

letter; as, gwan” weak; gtvynt, wind. Words primarily beginning with this

letter letter undergo two changes : they drop the g, and change it into Tig;

as, gairy a word, d” air, thy word, fi/ ngatr, my word. G is interchangeable

with c; as, godidog, excellent, godtdocach, more excellent, godidocaf, most

excellent; brag, malt, breci, wort; gwraig, a wife, gwreica, to take a wife;

teg, fair, tecach, fairer. G is also the vocal mutation of c; as, ci, a dog,

corgi, a cur, dwrgi, an otter, milgi, a greyhound.

12. Ng has the same sound as ng in sing. It sometimes commences a syllable in

Welsh, which it never does in English. Initial ng is the nasal mutation of g,

and, with h, of c; as, fy ngalar, my grief, from galar, grief; fy nghefn, my

back, from cefn, ba«k. It is never radical. [§ 3, note 2.]

13. H has the sound of h in the English words hard, high, hoarse, hurry. It

is never silent. With c, p, r, and t, this character forms ch, ph, rh, and

th, which re- present simple sounds, and not compounds of the sounds of c, p,

r, t, and h, as the characters might lead us to suppose. The letter A when

not preceded by ng, m, or n, is always followed by a vowel. When so preceded,

it may be followed by I, n, or r; as, fy nghlyw, my hearing; fy mhlant, my

children ; fy nhlodi, my poverty; fy nghnawd, my flesh; yng Nghred, in

Christendom; ym Mhrydain, in Britain; yn Nhrefaldwyn, in Montgomery; but it

is diffi- cult to determine whether the aspiration precedes or follows I, n,

r. Dr. Gruffydd Koberts, in his grammar (A.D. 1567), says h should be put

aitex I axv” t \w “xsiia. cases. %% b

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5518) (tudalen 006) (delwedd B5518) (tudalen 006)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

14. / has the sound of i in pin, and ee in meet. The diphthongal sound of the

English long e, as in spite, is nearly represented in Welsh by two letters,

ei or eu; as, eilun, an image ; teulu, a family. /, when followed by a, e” 0,

w, or 1/, in the same syllable, has the force of English y in yam, yet; as,

ia, ice; techyd, health; lonawr, Janu- ary; luddew, Jew; iyrchyn, a roebuck.

Before w it is less regular, being sometimes equal to ew in new, as others to

yoo; as niwl, a mist; lluniivyd, was formed. In jse, yes, % forms a separate

syllable.

15. jL has the power of the English /. L is never radical in purely Welsh

words : when found at the com- mencement of a word, either it is the vocal

mutation of II, or the word primarily begins with g; as, ei law, his hand,

from llaw, a hand; yr wyhren las, the blue sky, from glas, blue.

16. LL This letter represents a sound erroneously said to be peculiar to the

Welsh language. [§ 63.] In pro- nouncing it, the tongue assumes the same

position as in forming I, and the breath is forcibly propelled on each side

of the tongue, but more on one side than on the other. It is remarkable that

most persons breathe more on the right than on the left in pronouncing this

letter. [§ 62.} LI is subject to one mutation, being changed into Z; as Hid,

wrath, ei lid, his wrath. [§ 3, note 2.]

11, M has the same power as in English. It changes regularly into /; as, mah,

a son, dy fah, thy son. It is also the nasal mutation of h, and, with h, of

p; as, fy mrawd, my brother, fy mhechod, my sin, from brawd, a brother,

pechod, sin.

18. i\r, pronounced as in English, begins some words

which have no initial change, and is also the nasal muta-

“/on of d” and J with A, of (; as> fy nillad” xo” eVoJOsife-s*” %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5519)(tudalen 007) (delwedd B5519)(tudalen 007)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 7

from dillad, clothes; fi/ nhir, my land, from tir, land. It is liable to

change, for euphony, into m and ng; as am” mhur, impure, from an, negative,

and pur, pure; i/n, in, yng Nghaerdydd, in Cardiff. As in other languages, n

naturally takes the sound of ng before c ; as, llanc, a lad (rhyming with

hank English, pronounced hangk).

19. has the short sound of o in rvot. Its long sound is that of the French o;

not the diphthongal long Eng- lish 0, as in note. The difference between it

and the latter is, that in pronouncing the Welsh o, the lips assume a round

form before the sound is uttered; but the lips are moved while pronouncing

the English o, which is a union of a in all J and oo in too. is regularly

changed into y; as, com, a horn, cym, horns; aros, to wait, erys, will wait;

and irregularly into a and w; as” troed, a foot, traed, feet; croen, a skin,

crwyn, skins; oen, a lamb, fbyn, lambs. is a mutation of w and also of aw;

as, trwm (masculine), trom (feminine), heavy; tlodion, plural of tlawd, poor;

prawf, a proof, prvfi, to prove. The poets occasionally prefer aw to o; as,

teimlaw or teimlo, to feel; bythawl or bythol, everlasting.

20. P has the same power in Welsh as in English. It makes three changes;

namely, into b, mh, and ph; as, pen, a head, dy ben, thy head, fy mhen, my

head, ei pken, her head.

21. Fh has the power of ph and / in physical force* It is used in words

borrowed from other languages ; as, Phinehas, Ephesiaid; and in Welsh words

whose radical initial is p, of which it is the aspirate mutation; as, d

phlant, her children, from plant, children : in other cases ff is used.

22. Rh is not usually treated as oil” oi \)ti” \”\Xfcx” “\ the alphabet It

should, however, \\ko ch, pK, t\\”\>“ <i*”“- %% 8

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5520) (tudalen 008) (delwedd B5520) (tudalen 008)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

sidered as one letter: it represents a simple sound, and bears the same

relation to r as th does to dd. It is one of the mutable consonants, having r

for its vocal muta- tion, as rhaff, a rope, dwy raff, two ropes. Rh never

occurs at the end of a syllable. [§ 64.]

23. R has the same power as English r or rr, in rashj rugged, hurry,

pronounced strongly ; and never the softer sound of the English vocal r, as

in fear, curve, in pro- ducing which the tongue is curled a little further

back. The words here, more, boor, are pronounced as if written hee-ur, mo-ur,

boo-ur, and they differ in sound from the Welsh words hir, long, mor, the

sea, biur, strike thou, in the r only, which in the Welsh is a rough

articulation, while in the English it partakes so much of the vocal

character, that it is questionable whether it should not be considered a

vowel. R is the vocal mutation of rh. It never begins words in their radical

form. Words beginning with r (not rh) have undergone a mutation, and begin

radically either with rh or with g; as rhwyd, a net, dy rwyd, thy net; gras,

grace, ei ras, his grace.

24. S has the power of s in sin, ss in miss, or c in vice. In conjunction

with i, it is, in South Wales, generally pronounced like sh in shall; as,

siomi, to disappoint; sionc, brii”k ; this sound appears to have been

borrowed from the English ; but possibly it always existed amongst the

ancient Cymry. [§61.] With a diaeresis accent, s'i is pronounced see

(English), and forms a separate syllable; as, s'io, to hiss. The Welsh

language is destitute of the vocal sounds of s heard in the words pleasure

and raise.

25. T has always the sound of the English t, as in to, at; never that of t in

nature, nation. It is changed into d,

/lA, and th; as, tad, a father, ei dad, his father, fy nhad, my father, ei

thad, her father. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5521) (tudalen 009) (delwedd B5521) (tudalen 009)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 9

26. Th is of the same power as th in thick, thin, pith. It is never

pronounced like th in thei/, this, breathe. The Tocal spund of English th is

represented in Welsh by dd. Th is the aspirate mutation of t; as, tafod, a

tongue, ei thafod, her tongue. It is never radical.

27. U has sounds closely resembling those of / in this, and ee in meet. The

diphthongal sound of u, as in tune, is expressed in Welsh by itv; as, gwiw,

fit, meet; and nearly by uw or i/w; as, Duw, God; bi/w, living. [§ 30.]

28. W has the sounds of oo in good and boot. It is changed into o and y, and

sometimes by the poets into ei; as, Z/”w”“ (masculine), Horn (feminine),

bare; htvnw, that male (absent), hbno, that female (absent); dwfr, water,

dyfroedd or deifr, waters. In words radically beginning in chw or gw, w has

the force of w in well or u in quit; as, t(;ew, an inflection of gwen, gwyn,

white, pronounced exactly like wen English. The sound represented by wh in

when is not considered a genuine Welsh sound: in South Wales it takes the

place of chw.

29. T. The usual or primary sounds of y are like the short u in fun, and the

longer sound of the same letter in furze, but rather more guttural. In

monosyllables and in the last syllable of other words, it is pronounced like

the Welsh u, having nearly the power of ee in see, and that of i in thin. [§

30.] In dy, dyd, dyt, fy, myn, syr, y, ydd, ym, yn, yr, ys, yth, it has its

usual sounds. The two sounds occur in the words Cymry, Welshmen, and hyny, that

(absent), pronounced very nearly like the English word honey. Some of the

older writers used a character, some- thing like the Greek y, to represent

the usual sounds of y, writing the word Cymry thus, Cymry. Y was change- able

into y; as, dyn, a man, dymou, txi”tl” deTb-”-a” \» receive, derbyniais, I

received. But 7 -s”“a XiSjX* TssaXii”'“' %% 10

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5522) (tudalen 010) (delwedd B5522) (tudalen 010)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

The sound is still changed when a syllable is added. [§44.] F changes into «;

as, meZyw (masculine), melen (feminine), yellow; gwyn (masculine), gwen

(feminine), white. Y has two sounds in the Manx, as in Welsh.

30. The letters e, w, and y, it will be observed, have often nearly the same

sound : an accurate ear is requisite to detect the difference : the sounds of

u and the secondary sounds of y are identical : in pronouncing them the

tongue is held a little flatter than in pronouncing i; which has a thinner

sound, the passage between the tongue and the palate being more confined.

31. CA, dd, ffj ng, llj ph, rh, and th are inappropriate characters, their

component parts being in other situations separate letters. They are by some

called double letters ; but they represent simple sounds, perfectly distinct

from that of c, dy /, &c., and are not double in the same sense as Ji, fl

(equal to / t, / 0> ““ which the sounds of the separate letters are

retained.

32. The combinations ngh, mk, nh, which, unlike the foregoing digraphs [§

31], represent compound sounds, are placed in the alphabet by some

grammarians. There is an obvious impropriety in this method, which to be con-

sistent should also include aw, ai, and other combinations transmutable with

single letters.

33. The Welsh alphabet is free from some defects found in the alphabets of

many languages, no letter being ever silent, and no single letter being used

to express a com- pound sound, like the diphthongal a, i, o, and w, in

English, and the letter a?, which stands for ks or gz in extent and exalt y

and g, which in age stands for d and s as in pleasure; hence little more than

a knowledge of the names of the

)etters is necessary to enable a person to read the lan- “ia”e with

propriety. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5523) (tudalen 011) (delwedd B5523) (tudalen 011)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 11

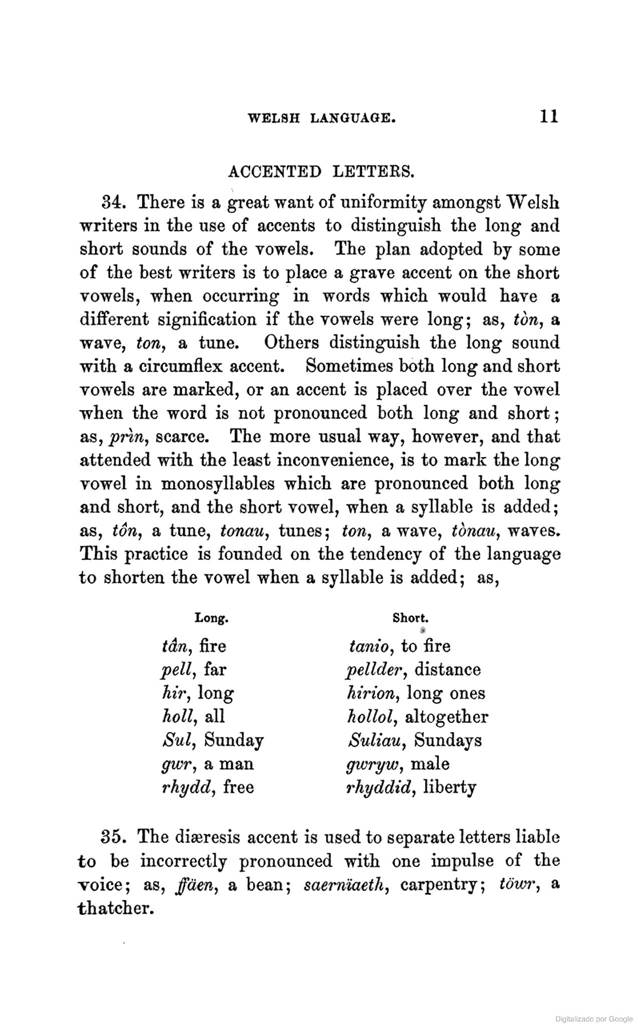

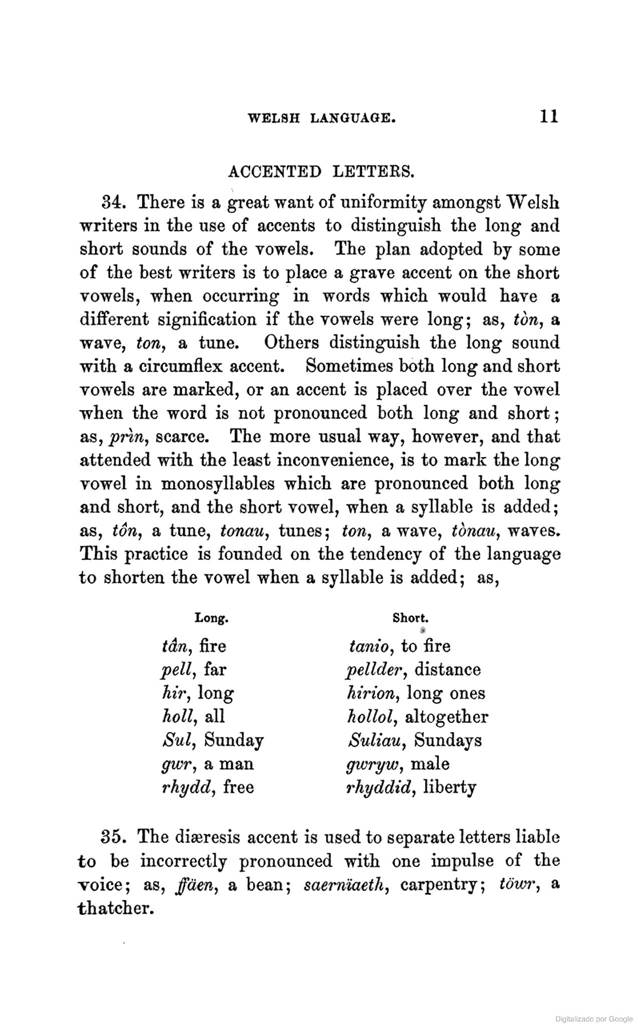

%% ACCENTED LETTERS. %% 34. There is a great want of uniformity amongst Welsh

writers in the use of accents to distinguish the long and short sounds of the

vowels. The plan adopted by some of the best writers is to place a grave

accent on the short vowels, when occurring in words which would have a

diflferent signification if the vowels were long; as, tbn” a wave, tortj a

tune. Others distinguish the long sound with a circumflex accent. Sometimes

both long and short vowels are marked, or an accent is placed over the vowel

when the word is not pronounced both long and short; as, priUj scarce. The

more usual way, however, and that attended with the least inconvenience, is

to mark the long vowel in monosyllables which are pronounced both long and

short, and the short vowel, when a syllable is added; as, toriy a tune,

tonau, tunes ; ton, a wave, tonau, waves. This practice is founded on the tendency

of the language to shorten the vowel when a syllable is added; as.

Long. Short.

tdn, fire faniOj to fire

pellj far pellder, distance

Air, long hiriorij long ones

hollj all holloly altogether

Sul, Sunday Suliau, Sundays

gvrr, a man gwryw, male

rhydd, free rkyddid, liberty

35. The diaeresis accent is used to separate letters liable to be incorrectly

pronounced with one impulse of the voice; as, ffden, a bean; saemiaetK,

cax”eviXx” \ Io-wt” “6. thatcber. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5524) (tudalen 012) (delwedd B5524) (tudalen 012)

|

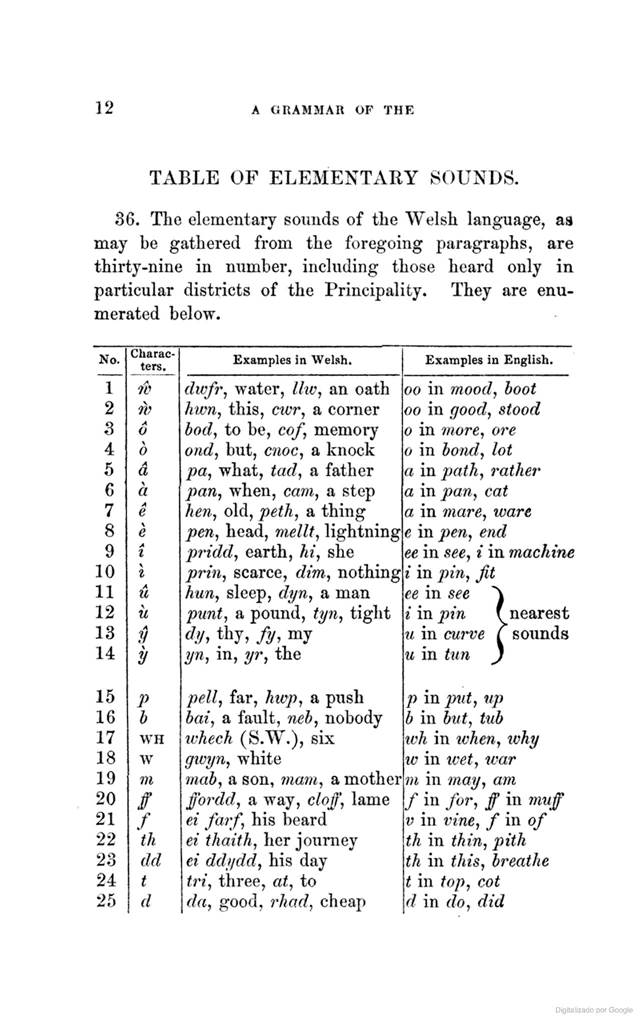

12 %% A ORAMMAR OF

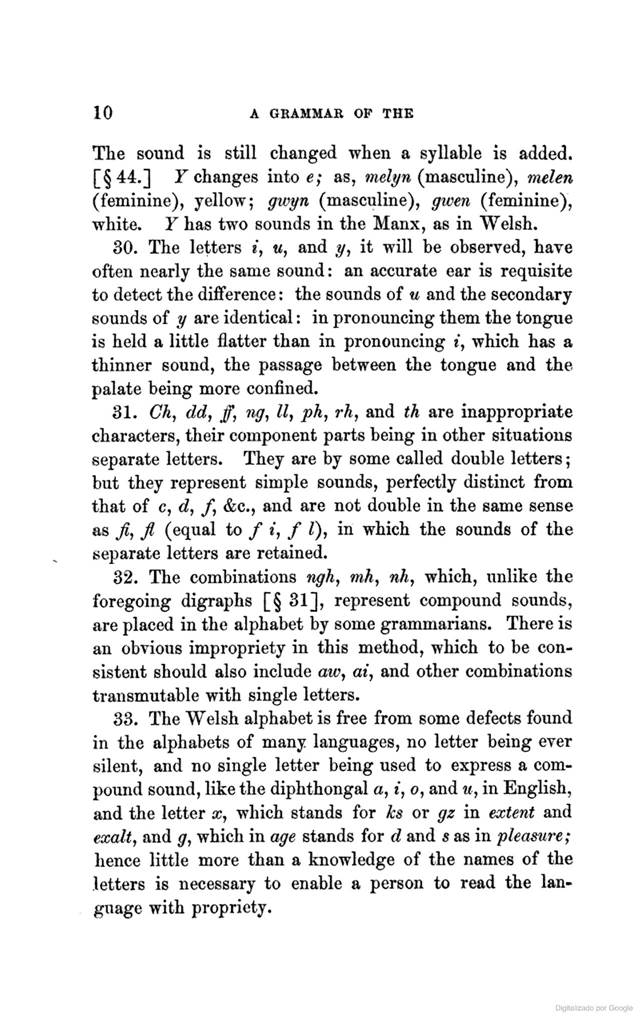

THE %% TABLE OF ELEMENTAKY SOUNDS.

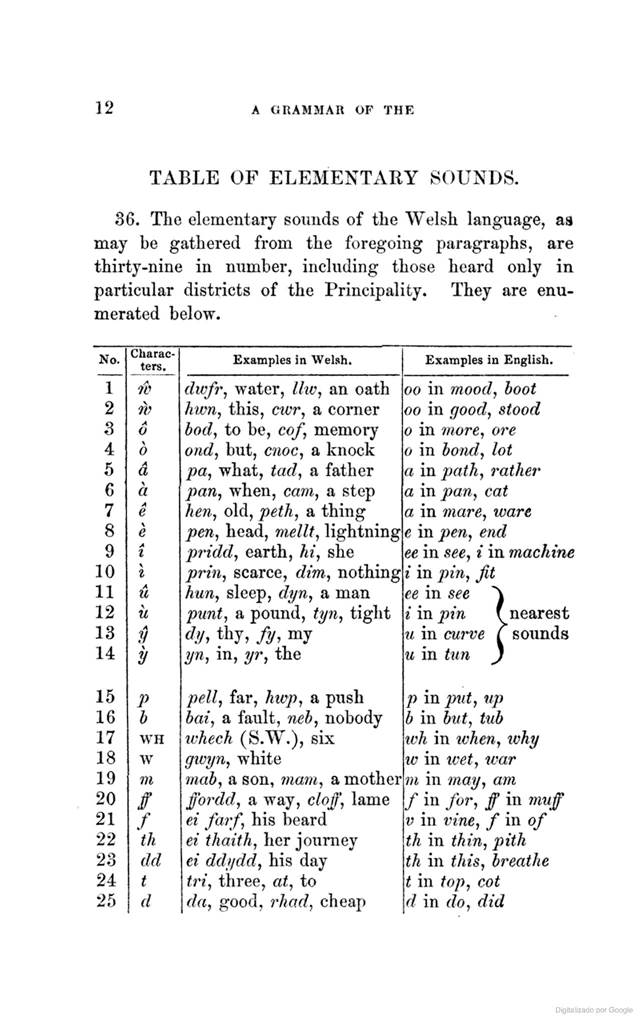

36. The elementary sounds of tlie Welsh language, as may be gathered from the

foregoing paragraphs, are thirty-nine in number, including those heard only

in particular districts of the Principality. They are enu- merated below. %%

No. %%Charac- ters. %%1 %%” %%2 %%ib %%3 %%6 %%4 %%b %%5 %%•d %%6 %%a %%7 %%A

e %%8 %%e %%9 %%t %%10 %%I %%11 %%{l %%12 %%u %%13 14 %%y %%15 16 %%p b %%17

%%WH %%18 %%W %%19 %%m %%20 21 22 %%/

/ th %%23 %%dd %%”4 %%/ %% Examples in Welsh. %% ““ / “ %% / %% dwfr, water,

llwj an oath hwn” this, cwr, a comer hod” to be, co/*, memory and” bilt,

cnoc, a knock pa” what, tad, a father. pan, when, cam, a step hen, old, peth,

a thing pen, head, mellt, lightning pridd, earth, hi, she prin, scarce, dim,

nothing hun, sleep, dyn,2i, man punt, a pound, tyn, tight dyj thy, fy, my yn,

in, yr, the

pell, far, hv)p, a push hai, a fault, we5, nobody whech (S.W.), six gioyn,

white

wa5, a son, warn, a mother ffordd, a way, cZojf, lame ei farf, his beard ei

thaith, her journey €2 ddydd, his day /r”“ three, at, to “<?, “ood,

rAdw;?, cheap %% Examples in English. %% 00 in mood, boot

00 in good, stood

in Tnore, ore

in 6owc?, Zoi

a in jpa”A, rather

a in “an, ca<

a in mare, ware

e in jE)ew, end '

ee in 5e€, i in machine

i in j?m, “i

ee in see "\

i in “tw f nearest

u in cwrve “ sounds

u in “ww “

j? in put, up b in but, tub wh in tf”Aew, why w in t(;ei, i”?ar m in ma”, am

/ in for, ff in mw/ V in vine, / in of th in <Am, j[?tYA th in “Ais,

breathe t in fo/), co< \d in do, did %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5525) (tudalen 013) (delwedd B5525) (tudalen 013)

|

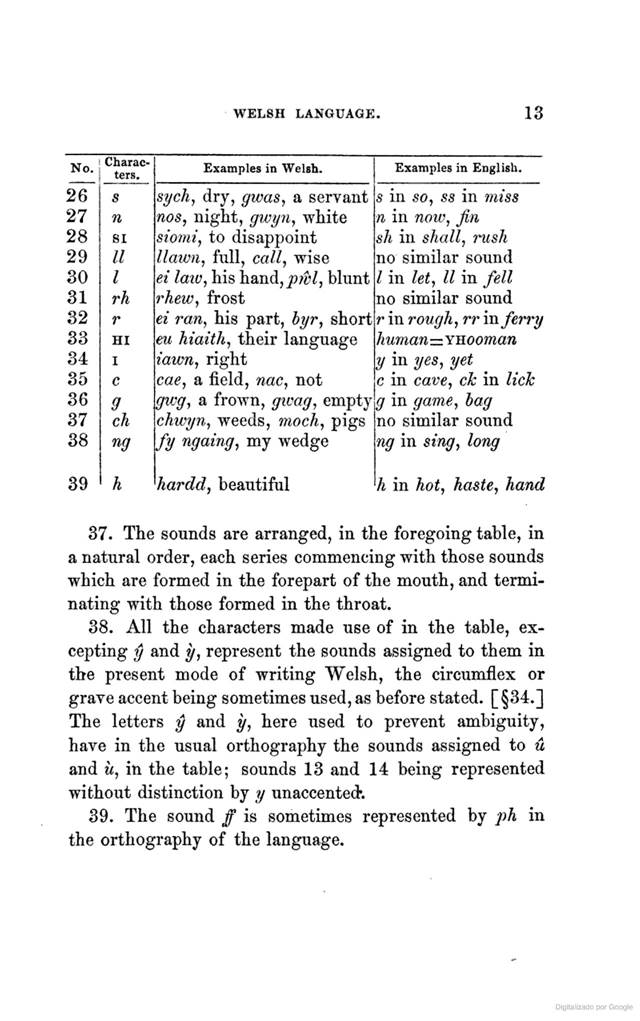

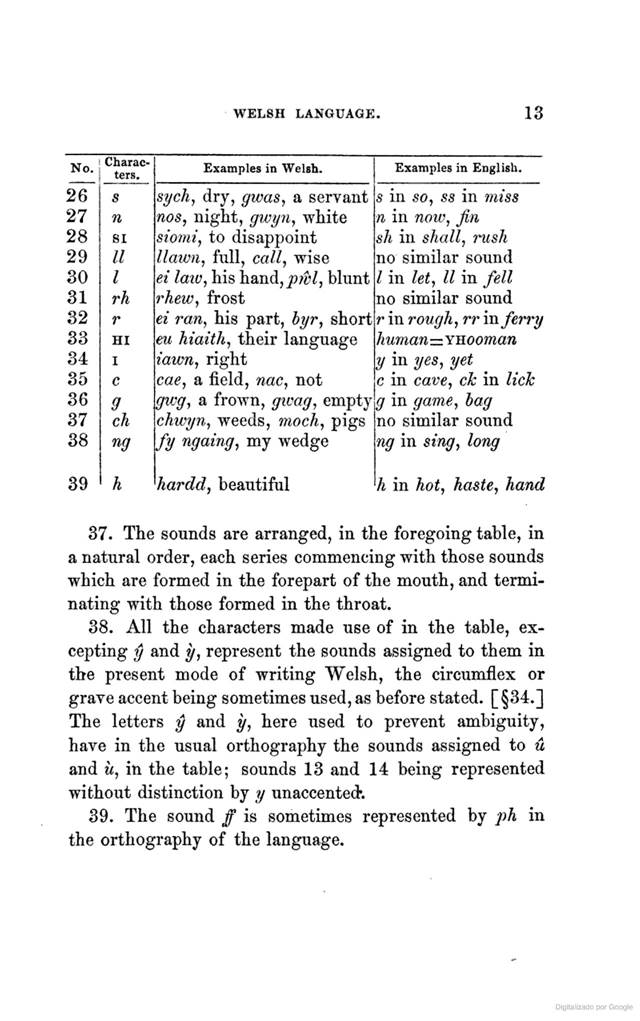

WELSH LANGUAGE. %%

18 %% No. %%Charac- ters. %%Examples in Welsh. %%Examples in English. %%26 27

28 29 %%S

n

SI 11 %%st/ch, dry, gwas, a servant nos, night, gw7/n, wMte stomij to

disappoint llawn, full, callj wise %%s in SO, ss in miss n in now, fin sh in

shall, rush no similar sound %%30 31 %%I

rh %%ei law, his hand, pfbl, blunt rhew, frost %%I in Ze<, ZZ in fell no

similar sound %%32 33 %%r

HI %%ei ran, his part, b”r, short eu hiaithy their language %%r in rough, rr

in ferry human=iYKooman %%34 35 %%I c %%iawn, right

ca£, a field, imcj not %%y in yes, yet “

c in cave, ck in lick %%36 37 %%9 ck %%gwg, a frown, gwag, empty chvjyn,

weeds, moch, pigs %%g in “aw«, fta”' no similar sound %%38 %%ng %%fy ngaing,

my wedge %%ng in sing, long %%39 %%h %%hardd, beautiful %%h in Aof, haste,

hand %% 37. The sounds are arranged, in the foregoing table, in a natural

order, e”ch series commencing with those sounds which are formed in the

forepart of the mouth, and termi- nating with those formed in the throat.

38. All the characters made use of in the table, ex- cepting “ and y,

represent the sounds assigned to them in the present mode of writing Welsh,

the circumflex or grave accent being sometimes used, as before stated. [§34.]

The letters “ and y” here used to prevent ambiguity, have in the usual

orthography the sounds assigned to tl and u, in the table; sounds 13 and 14

being represented without distinction by y unaccented.

39. The sound / is sometimes represented by ph in the orthography of the language.

%% 14

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5526) (tudalen 014) (delwedd B5526) (tudalen 014)

|

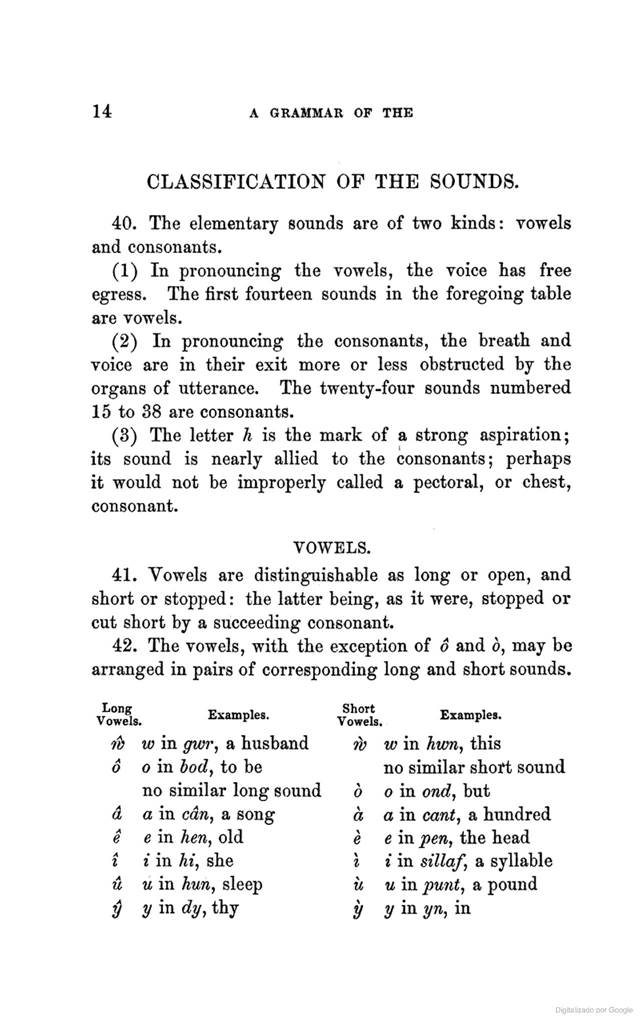

A GRAMMAR OF THE %%

CLASSIFICATION OF THE SOUNDS.

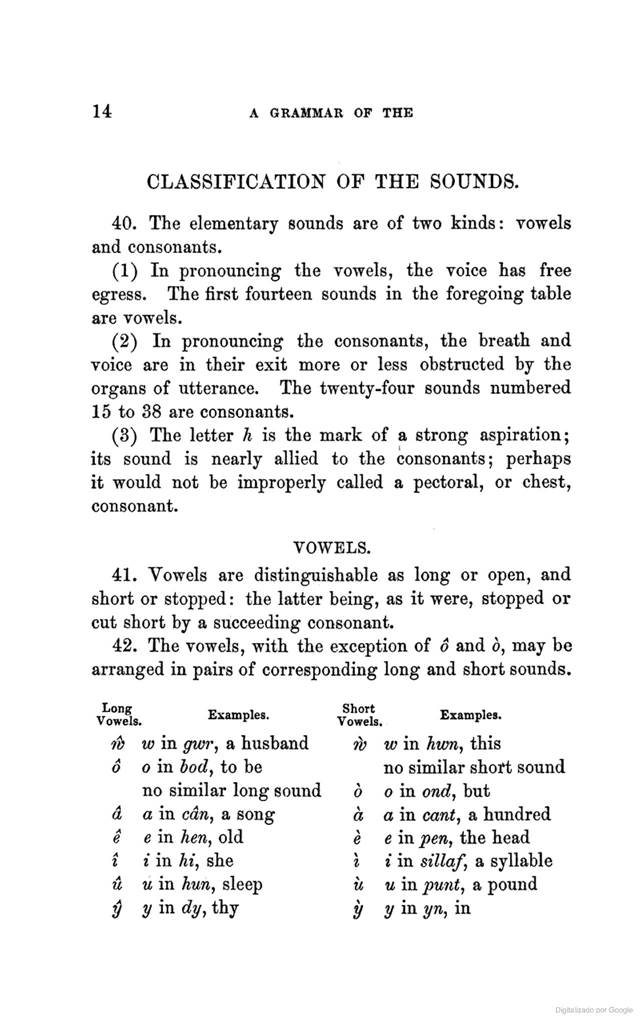

40. The elementary sounds are of two kinds: vowels and consonants.

(1) In pronouncing the vowels, the voice has free egress. The first fourteen

sounds in the foregoing table are vowels.

(2) In pronouncing the consonants, the breath and voice are in their exit

more or less obstructed by the organs of utterance. The twenty-four sounds

numbered 15 to 38 are consonants.

(3) The letter h is the mark of a strong aspiration; its sound is nearly

allied to the consonants; perhaps it would not be improperly called a

pectoral, or chest, consonant.

VOWELS.

41. Vowels are distinguishable as long or open, and short or stopped : the

latter being, as it were, stopped or cut short by a succeeding consonant.

42. The vowels, with the exception of 6 and o, may be arranged in pairs of

corresponding long and short sounds.

V”owds. Examples. “““““ Examples.

1” win givr, a husband “ w in hwn, this

6 in hod” to be no similar short sound

no similar long sound b o in ondj but

d a in cdn, a song a a in cant, a hundred

e e in hen, old e « in pen, the head

I i in hi, she i i in sillaf, a syllable

“ u in huriy sleep h uin punt” a pound

“ “ in d”y tbjr y j/ m yu, m %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5527) (tudalen 015) (delwedd B5527) (tudalen 015)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 15

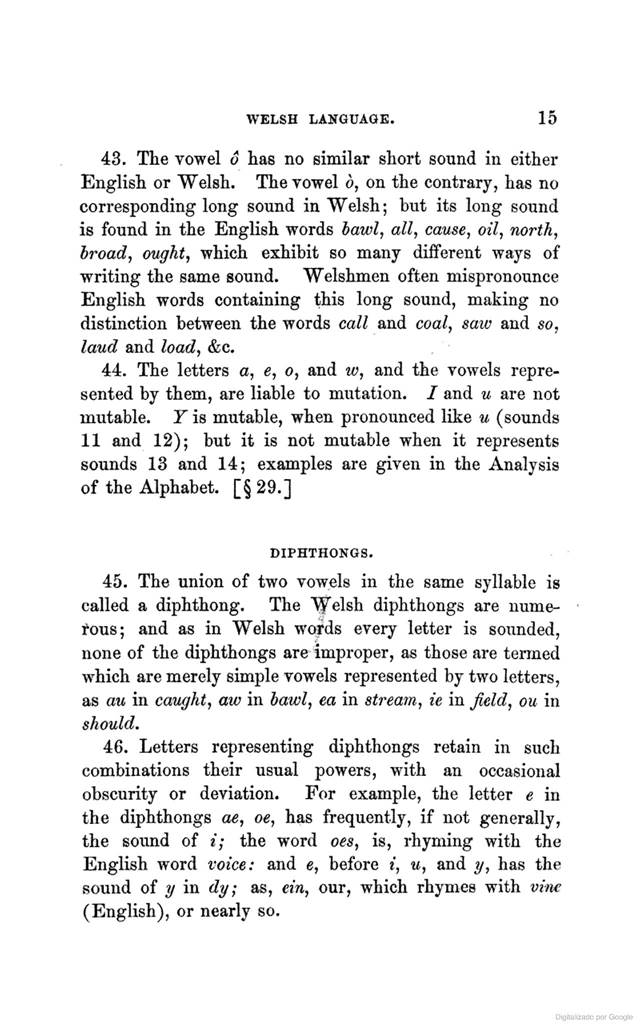

43. The vowel 6 has no similar short sound in either English or Welsh. The

vowel o, on the contrary, has no corresponding long sound in Welsh; but its

long sound is found in the English words bawl, all, cause, oil, north, broad,

ought, which exhibit so many different ways of writing the same sound.

Welshmen often mispronounce English words containing this long sound, making

no distinction between the words call and coal, saw and so, laud and load,

&c.

44. The letters a, e, o, and w, and the vowels repre- sented by them, are

liable to mutation. / and u are not mutable. Y is mutable, when pronounced

like u (sounds 11 and 12); but it is not mutable when it represents sounds 13

and 14; examples are given in the Analysis of the Alphabet. [§29.] %%

DIPHTHONGS.

45. The union of two vowels in the same syllable is called a diphthong. The

Welsh diphthongs are nume- rous; and as in Welsh words every letter is

sounded, none of the diphthongs are improper, as those are termed which are

merely simple vowels represented by two letters, as at” in caught, aw in

bawl, ea in stream, ie in field, ou in should,

46. Letters representing diphthongs retain in such combinations their usual

powers, with an occasional obscurity or deviation. For example, the letter e

in the diphthongs ae, oe, has frequently, if not generally, the sound of i;

the word oes, is, rhyming with the English word voice: and e, before i, u,

and y, has the Bound of y in dy; as, ein, our, whick iYv”txv”“ ““VOtv mxv«.

(English), or nearly so. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5528) (tudalen 016) (delwedd B5528) (tudalen 016)

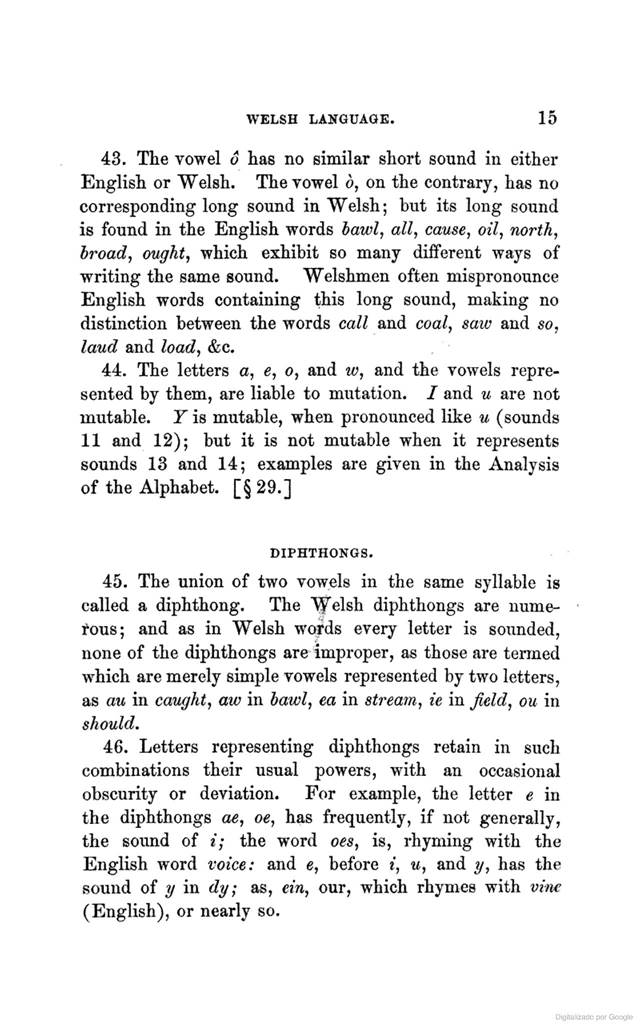

|

16 %% A GRAMMAR OF

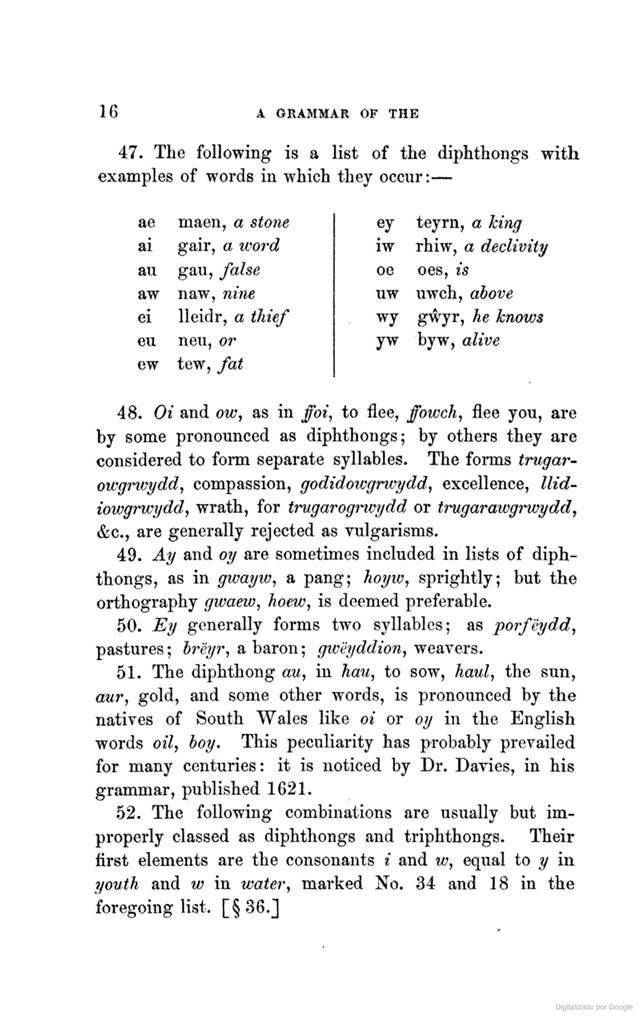

THR %% 47. The following is a list of the diphthongs with examples of words

in which they occur: — %% ae %%maen, a stone %%■ ey %%teyrn, a king

%%ai %%gair, a word %%iw %%rhiw, a declivity %%au %%gau, false %%oe %%oes, is

%%aw %%naw, nine %%uw %%uwch, above %%ei %%Ueidr, a thief %%wy %%g”r, he

knows %%eu %%neu, or %%yw %%byw, alive %%ew %%tew, fat %%%%

48. Oi and ow, as in ffoi, to flee, ffowch, flee you, are by some pronounced

as diphthongs; by others they are considered to form separate syllables. The

forms trugar-” owgrwyddy compassion, godidowgrwydd, excellence. Hid-

iowgrwyddj wrath, for trugarogrwydd or tragarawgrwydd, &c., are generally

rejected as vulgarisms.

49. Ay and oy are sometimes included in lists of diph- thongs, as in gwayw, a

pang; hoyw, sprightly; but the orthography gwaew, hoew, is deemed preferable.

50. Ey generally forms two syllables; as porfeyddy pastures ; breyr, a baron

; gweyddion, weavers.

51. The diphthong aw, in hau, to sow, haul, the sun, aur” gold, and some

other words, is pronounced by the natives of South Wales like oi or oy in the

English words oily hoy. This peculiarity has probably prevailed for many

centuries: it is noticed by Dr. Davies, in his grammar, published 1621.

52. The following combinations are usually but im- properly classed as

diphthongs and triphthongs. Their flrst elements are the consonants i and w,

equal to y in

j<{?u”k and w in water “ marked No. 34 and 18 in the “ores”oing list.

[§36.] %% WEL8H LANOUAGB. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5529) (tudalen 017) (delwedd B5529) (tudalen 017)

|

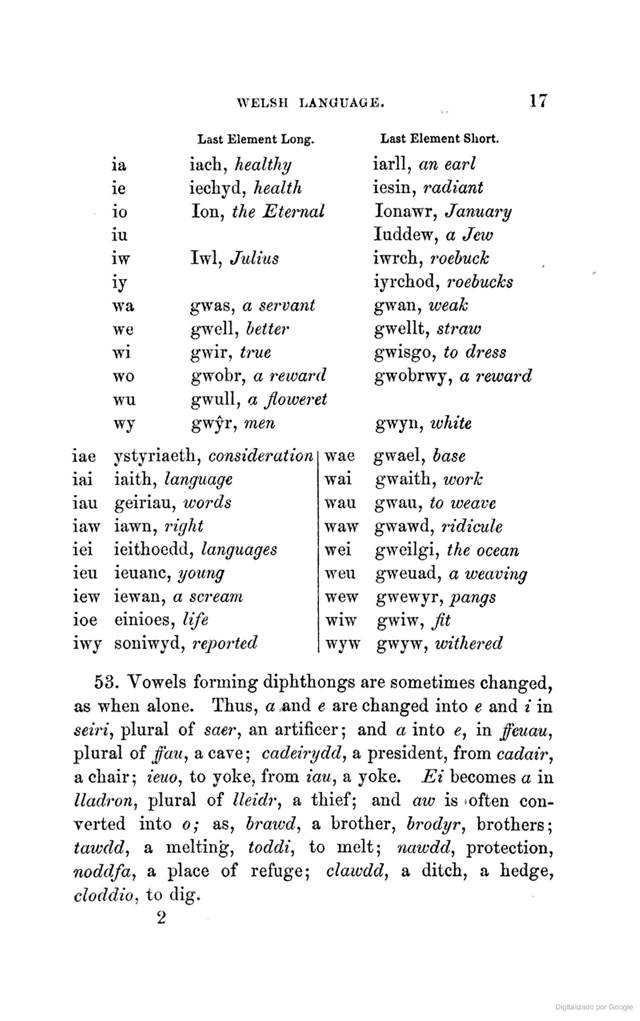

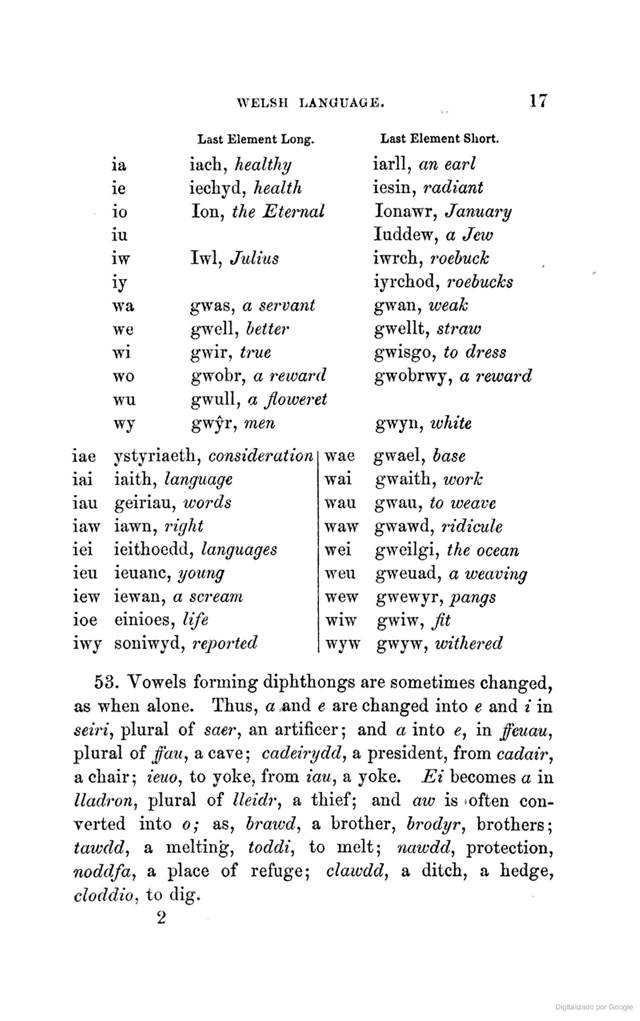

17 %%%%

Last Element Long. %%

Laat Element Short. %%

ia %%iach, healthy %%iarll, an earl %%

ie %%iechyd, health %%iesin, radiant %%

io %%Ion, the Eternal %%lonawr, January %%

iu %%

luddew, a Jew %%

iw %%Iwl, Julius %%iwrch, roebuck %%

iy %%• %%iyrchod, roebucks %%

wa %%gwas, a servant %%gwan, weak %%

we %%gwell, better %%gwellt, straw %%

wi %%gwir, true %%gwisgo, to dress %%

wo %%gwobr, a reward %%gwobrwy, a reward %%

wa %%gwuU, a floweret %%%% wy %%gwfr, men %%gwyn, white %%B %%ystyriaeth,

consideration %%wae %%gwael, base %%•

I %%iaith, %%language %%wai %%gwaith, work %%a %%geiriau, wo7'ds %%wau

%%gwau, to weave %%w %%iawn, %%right %%waw %%gwawd, ridicule %%1

I %%ieithoedd, languages %%wei %%gweilgi, the ocean %%a %%ieuanc, young %%weu

%%gweuad, a weaving %%w %%iewaD %%, a scream %%wew %%gwewyr, pangs %%e

%%einioes, life %%wiw %%gwiw, fit %%7 %%soniw %%yd, reported %%wyw %%gwyw,

withered %% 63. Vowels forming diphthongs are sometimes changed, when alone.

Thus, a and e are changed into e and i in jW, plural of saer” an artificer ;

and a into 6, in ffeuau” oral of ffau, a cave ; cadeirydd, a president, from

cadair, chair ; ieuo, to yoke, from iau, a yoke. Ei becomes a in idroUj

plural of lleidr, a thief; and aw is often con- srted into o; as, brawd, a

brother, brodyr, brothers; wdd, a melting, toddi, to melt; nawdd, protection,

*ddfay a place of refuge; clawdd” “ dVlOa., “ V”\%”“ 7if(/io, to dig. 2 %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5530) (tudalen 018) (delwedd B5530) (tudalen 018)

|

18 A GRAMMAR OF THB

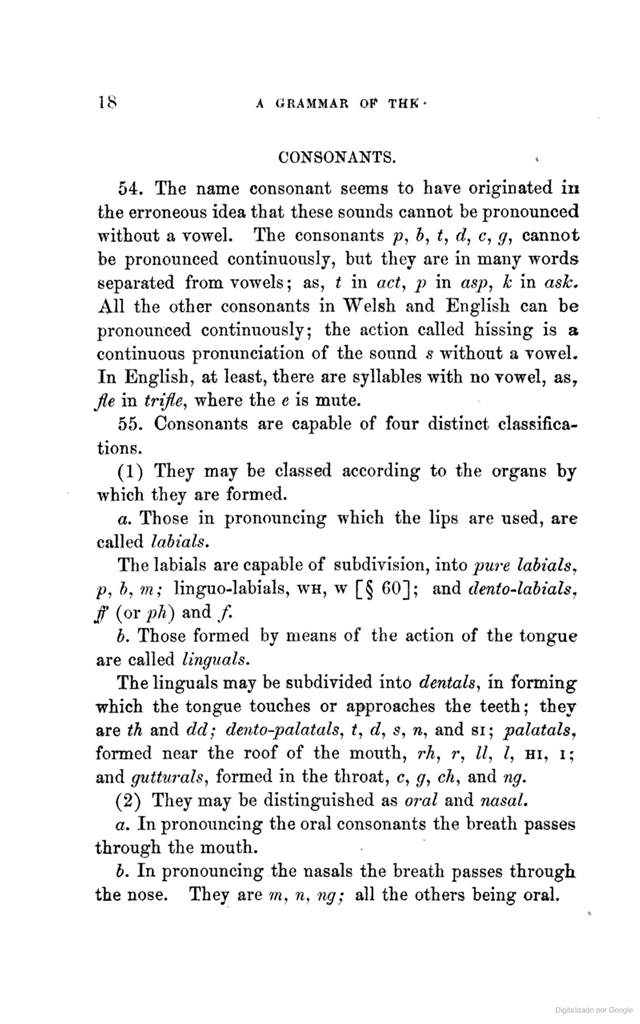

CONSONANTS.

54. The name consonant seems to have originated in the erroneous idea that

these sounds cannot be pronounced without a vowel. The consonants p, 5, t, d,

c, g, cannot be pronounced continuously, but they are in many words separated

from vowels ; as, t in act, p in asp, k in ash All the other consonants in

Welsh and English can be pronounced continuously; the action called hissing:

is a continuous pronunciation of the sound s without a vowel. In English, at

least, there are syllables with no vowel, as, Jle in trifie, where the e is

mute.

55. Consonants are capable of four distinct classifica- tions.

(1) They may be classed according to the organs by which they are formed.

a. Those in pronouncing which the lips are used, are called labials.

The labials are capable of subdivision, into pure lahiaUj p, b, m;

linguo-labials, wh, w [§ 60]; and dento-labials, ff (or ph) and /.

b. Those formed by means of the action of the tongue are called Unguals,

The linguals may be subdivided into dentals, in forming which the tongue

touches or approaches the teeth ; they are th and dd; dento-palatals, t, d,

s, n, and si; palatals, formed near the roof of the mouth, rh, r, II, I, hi,

i; and gutturals, formed in the throat, c, g, ch, and ng,

(2) They may be distinguished as oral and nasal,

a. In pronouncing the oral consonants the breath passes through the mouth.

b. In pronouncing the nasals the breath passes through i”/te nose. They are

m” n, ng; all tlie ot\ieta\iem% at«“.. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5531) (tudalen 019) (delwedd B5531) (tudalen 019)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 19

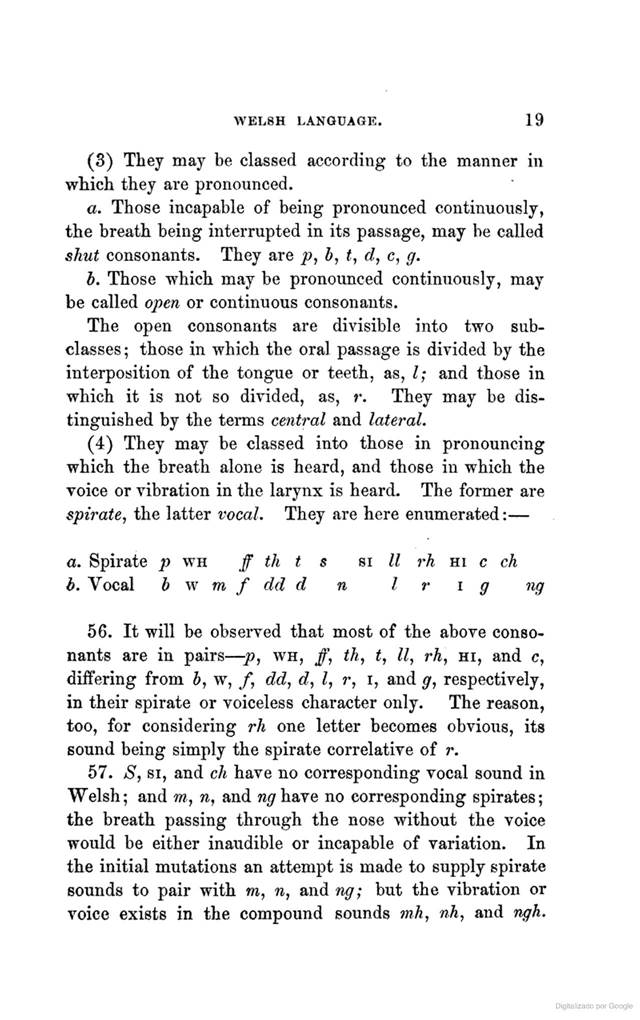

(3) They may be classed according to the manner in rhich they are pronounced.

a. Those incapable of being pronounced continuously, he breath being

interrupted in its passage, may be called hut consonants. They are p, b, tj

d, c” g.

h. Those which may be pronounced continuously, may >e called open or

continuous consonants.

The open consonants are divisible into two sub- lasses ; those in which the

oral passage is divided by the nterposition of the tongue or teeth, as, I;

and those in rhich it is not so divided, as, r. They may be dis- ingnished by

the terms central and lateral.

(4) They may be classed into those in pronouncing rhich the breath alone is

heard, and those in which the oice or vibration in the larynx is heard. The

former are pirate, the latter vocal. They are here enumerated : —

;. Spirate p wh ff th t s bi U rh hi c ch . Vocal b w m f dd d n I r i g ng

66. It will be observed that most of the above conso- lants are in pairs — p,

wh, jf, th, t, II, rh, hi, and c, liffering from b, w, /, dd, d, I, r, i, and

g, respectively, Q their spirate or voiceless character only. The reason, 00,

for considering rh one letter becomes obvious, its onnd being simply the

spirate correlative of r.

67. S, 81, and ch have no corresponding vocal sound in “iTelsh ; and m, n,

and ng have no corresponding spirates ; he breath passing through the nose

without the voice ronld be either inaudible or incapable of variation. In he

initial mutations an attempt is made to supply spirate onnds to pair with m,

n, and ng ; Wt Wift V”x”vycL “t owe exists in the compound Bounds mh, uh, ««A

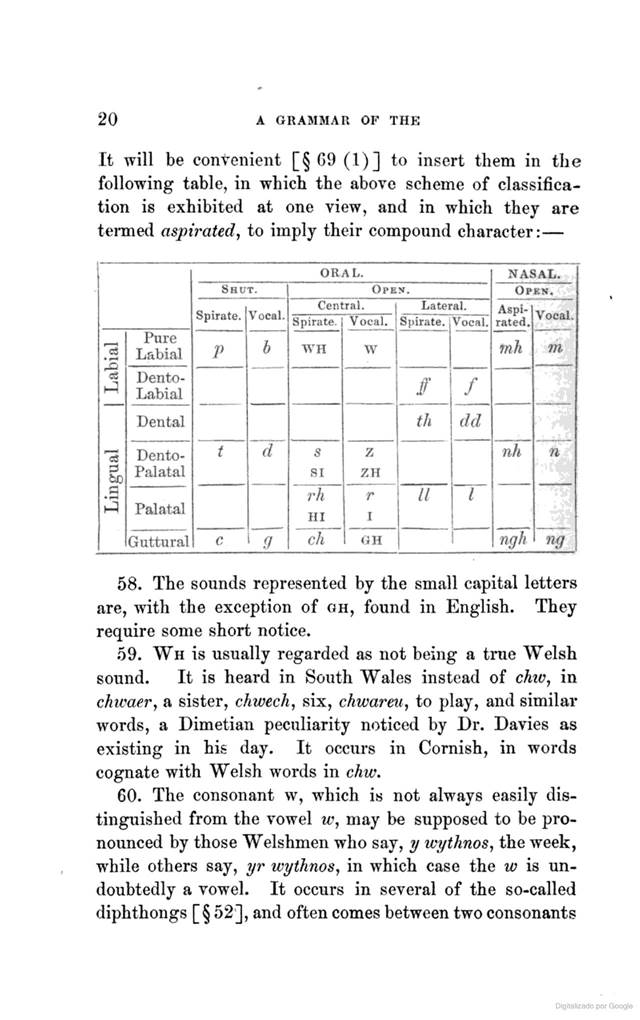

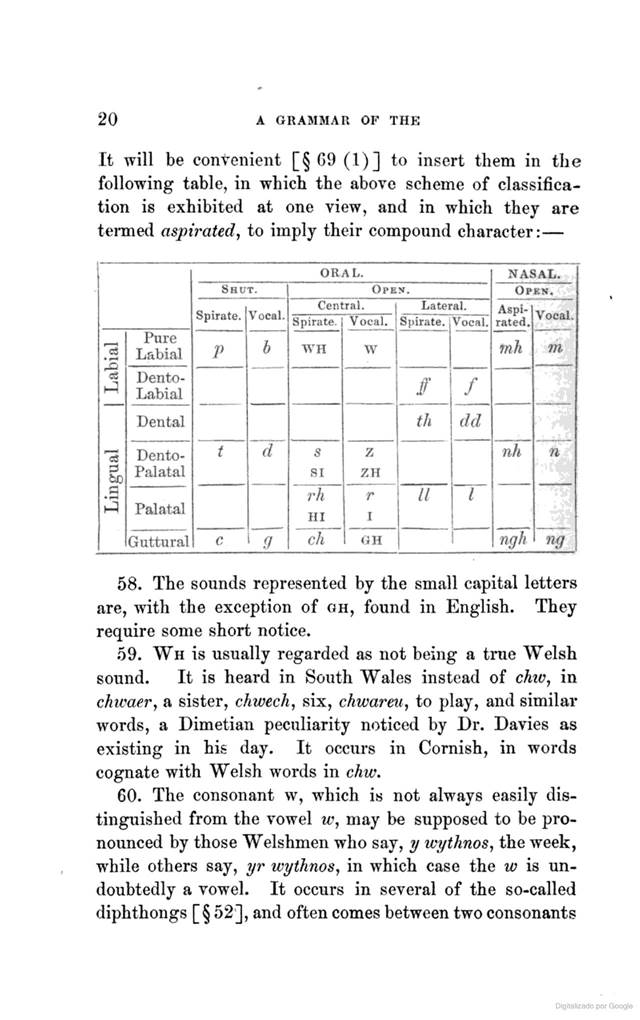

•kv”'Vv, %% It will be convenient [§ 69 (1)] to insert them in the following

table, in which the above scheme of classifica- tion is exhibited at one

view, and in which they are termed aspirated, to imply their compound

character: — %%%%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5532) (tudalen 020) (delwedd B5532) (tudalen 020)

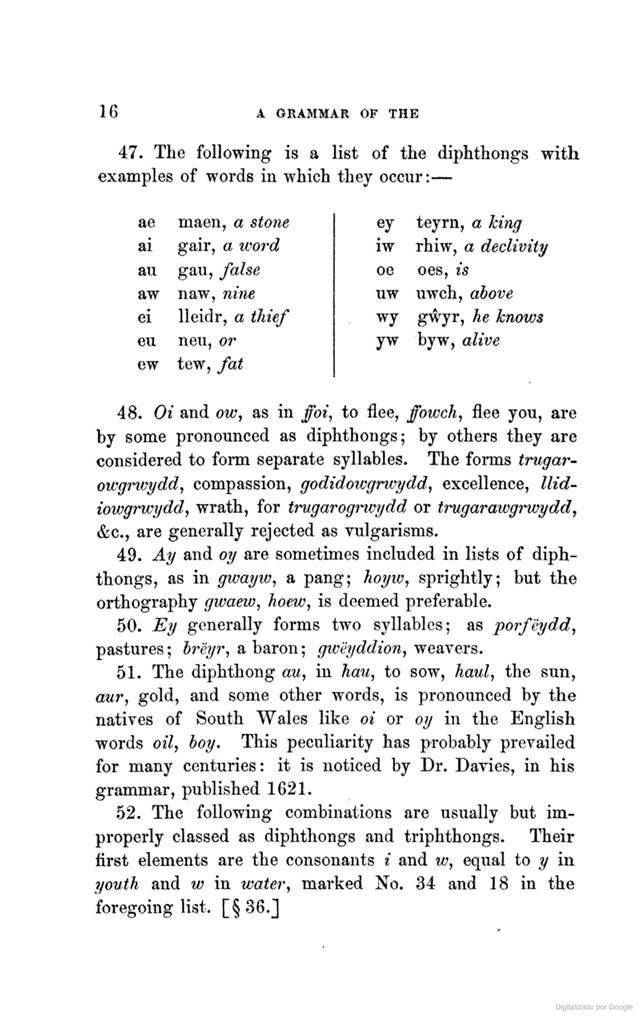

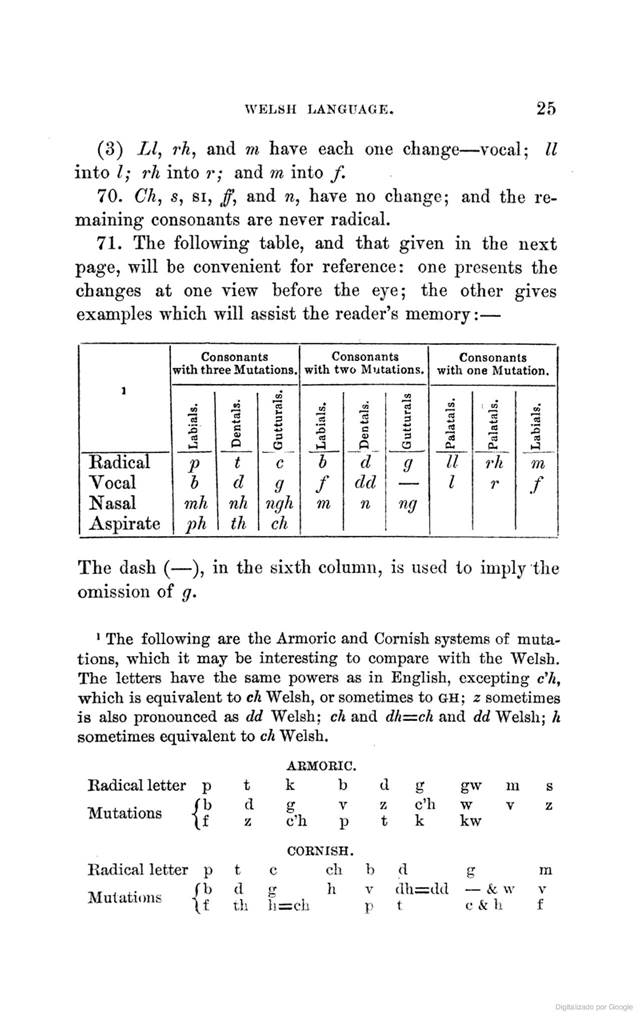

|

ORAl,, %%NASAi. 1

%%%%%%o,». 1 %%Splrate. %%V«.l. %%C”nltal. %%L«er<l. %%A-Pl- %%Vocil.

%%SpitBt”. %%

Si.lrnU. %%

1

1 %%Pare Labial %%}> %%6 %%

“L %%/ %%f %%mh %%” %%Dento-

Labial %%%% Dental %%%%%%

Ih %%dd %%%% Dento- PalatJil %%f %%d %%81 %%L %%%% ■nk %%n %%Palatal %%

IT %%rh %%r %%u %%I %%%% tJntturu,! %%cU %%CU %%%% ngh %%nfi %% 5S. The

sonnde represented by the small capital letters are, with the exception of

oh, fonnd in English. They require some short notice.

59. Wh is uenally regarded as not being a trae Welsh sound. It is heard in

South Wales instead of ckw, in chwaer, a sister, chwech, six, chwareu, to

play, and similar words, a Dimetian peciiliarity noticed by Dr. Davies as

existing in hit day. It occurs in Cornish, in words cognate with Welsh words

in ckw.

CO. The consonant w, which is not always easily dis- tingnished from the

vowel w, may be supposed to be pro- nounced by those Welshmen who say, y

wythnos, the week, while others say, yr wytktws, in which case the w is un-

doabteA\j a vowel. It occurs in several of the so-called (///(Ai”Ofl”sf J52

J, and often comes t”fiftentw'i'aniwi-aa.n.ti %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5533) (tudalen 021) (delwedd B5533) (tudalen 021)

|

W«L8H LANGUAGE. 21

without forming a separate syllable, as in the monosyllables gwlad, a

country, gturaig, a wife, which is not the case with any vowel. The sound w

seems to possess an affinity for guttural consonants: we find it after “ in a

great many Welsh words, and it invariably follows initial ch when radical, as

u does q in Latin and English. This arises from the fact that the letter w

represents a mixed sound, which is formed partly by the back part of the

tongue and partly by the lips — a distinction it has not been thought

necessary to indicate in the table.

61. The vocal consonants z and zh (z in zeal and s in pleasure) do not occur

in Welsh, but both are found in the Armoric, or Celto-Breton, that branch of

the Celtic which most closely resembles the Welsh. In Armoric, z, zh, SI, are

represented by Zy j, ch, which characters have the same power in French. The

Armoric Britons probably borrowed the sounds, as they doubtless have the

charac- ters from their French neighbours; for, according to Le Gonidec, the

pronunciation of z, j, and ch is not uniform, z being often pronounced like

dd Welsh, while j and ch were formerly written and are still often pronounced

t and 8. This supports the opinion that Welsh ai (the pronunciation of which

also is not uniform) has been borrowed from the English. Carnhuanawc was of

opinion that the sound si always existed amongst some of the Welsh people.

Many natives of North Wales are unable to pronounce it. It is remarkable that

this sound is represented in most languages by two or more characters ; by sh

in English, ch in French and Portuguese, sch in German, set in Italian.

62. The sound II is generally a great stumbling-block to learners. The power

of pronouncing it may be ac(\aired by observing the process followed in

“«i;aOTi” ix«ai *v”“ %% 22

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5534) (tudalen 022) (delwedd B5534) (tudalen 022)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

sound /, ddy z, zh, to /*, th, s, si, and imitating that process with I, when

II will be produced. Thus, let the word strive be pronounced, and the last

sound, v, be dwelt upon (continued, not repeated), striv-v-v, and let the

sound V be changed, without pausing, into /■/■/, making the word

strife. This will be effected by simply dropping the voice, and breathing a

little more forcibly. In like manner wreathe may be converted into ivreath,

peas into peace, or badge (bad”A) into batch (batsA). The same process, pdUUl

— ll-ll-ll, would convert pal, a spade, into pall, cessation, and the Welsh

II would be soimded. LI is not, however, the exact correlative of I : both

are formed with the tip of the tongue; but, in sounding II, the front or

upper part of the tongue is raised a little so as to contract the passage of

the breath.

63. Both II and its true vocal correlative are found in the Zulu language.

Camhuanawc remarks that the sound II is said to be found amongst some tribes

of the Caucasus. He also suggests that the French may have had a sound

similar to that of II, and that the various modes of writing some old French

names, as Lothair, Clotair, Chlotar, Lhotar, may have arisen from efforts to

represent it. It is sometimes said to have an equivalent in the Spanish II;

this, however, is an error. The Welsh II is spirate, while the Spanish II is

vocal and bears the same relation to i (y in yes), as I does to r. Thus, I

and r are formed by raising the tip of the tongue towards the roof of the

mouth; but in I the breath passes each side of the tongue, while in r it

passes over the middle: that is, Z is lateral, and r is central. In like

manner Spanish II and i are formed, not with the tip, but by pressing the

front or vpper part of the tongue against the palate; both are wocalaad open;

but JSpanish II is lateral, “liWe” \ \a <i«?cA?tiJL, %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5535) (tudalen 023) (delwedd B5535) (tudalen 023)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 23

64. The sound rh may be produced by continuing the sound r, and dropping the

voice as directed with reference to ZZ [§ 62]: thus the English word ran may

be changed into the Welsh rhan, a part; r-r-r'Th-rh-rhan. This sound is found

in French words ending in tre, ere, pre; as etre, to be, fiacre, a kind of

carriage, propre, proper.

65. The soimd ch may be produced by pronouncing a final k, and relaxing the

contact of the organs, so as to allow a rough-sounding impeded breathing:

ek-k-ch-ch-ch,

66. The sounds hi (the first sound in the word humid y”oomid) and i are

certainly sometimes heard in Welsh, the hi in eu hiaith, their language, and

i in iaith, being, as pronounced by some Welshmen at least, equivalent to the

initial sounds of human and yard. Hence some writers have y iaith, others yr

iaith, the language; these treating i as a vowel, those deeming it a

consonant.

67. In the bardic alphabet, Coelbren y Beirdd, there occurs a character, by

the substitution of which for that equivalent to “ in the modem alphabet, the

soft mutation of words radically beginning with g, was made. This suggests

the inference that the Welsh formerly possessed a sound it has not now ; and

analogy [§75] leads to the conclusion that the sound in question is the vocal

correlative of ch, which would be naturally represented by OH, and can be

easily produced by any Welshman who will take the trouble to observe the

process followed in passing from the sound th to dd, and imitate that process

with respect to ch. According to Edward Lhuyd, this sound is to be found in

the Armoric; and the writer can corro- borate this statement, having heard it

pronounced by natives of Brittany, and that too precisely in the situation

analogy would induce us to expect it: cK m Kxt£iofvR.\i«vs!L% univalent to

sk, the Welsh ch is Tepxe”erLt” <?h.; \sv>“V” %% 24

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5536) (tudalen 024) (delwedd B5536) (tudalen 024)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

found the c'A pronounced gh in da c”halloud” thy power, from galloud, power.

The sound ©h is by Lhuyd said to occur in Gaelic; it is also heard in an

affected pronuncia- tion of the French, the word vraiment being offcen pro-

nounced in Paris as if written vghaiment, and it is substituted for the same

sound (r) by the illiterate in Northumberland and Durham, a corruption

arising from the circumstance that the two sounds are produced in very nearly

the same part of the mouth, while they agree in being oral, vocal, open,

central, and continuous. Probably the sound existed in English words where we

find the cha- racters gh silent, as in night, a guttural sound being still

re- tained in this word in Scotland, as well as in the equivalent German word

nachU According to continental scholars, the Hebrew r (am), considered mute

by Englishmen, bore the sound gh; but Dr. Davies asserts it to be identical

with ng,

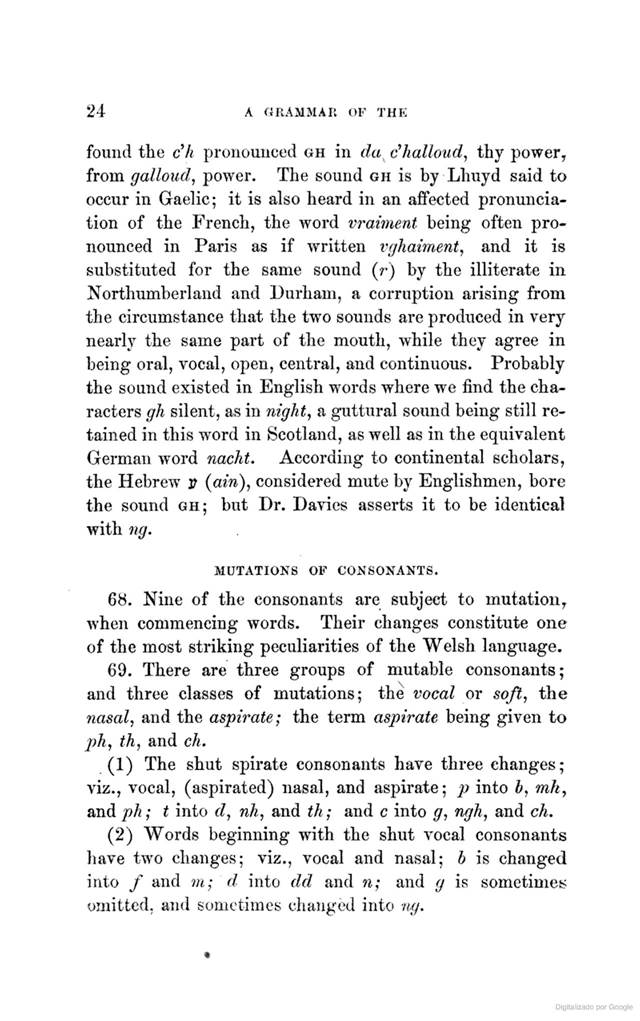

MUTATIONS OF CONSONANTS.

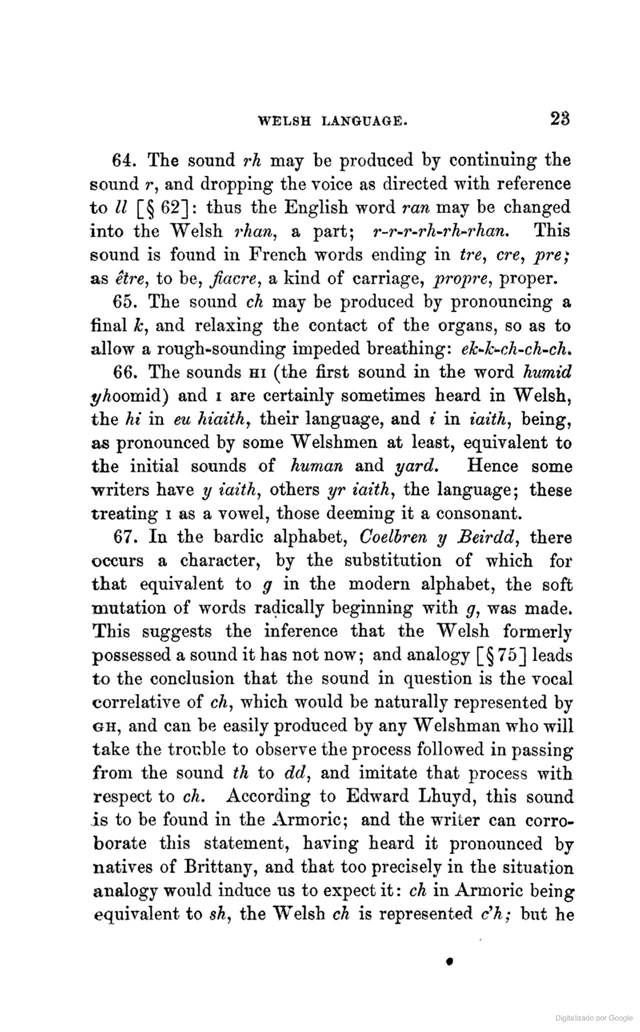

68. Nine of the consonants are subject to mutation, when commencing words. Their

changes constitute one of the most striking peculiarities of the Welsh

language.

69. There are three groups of mutable consonants; and three classes of

mutations; the vocal or soft, the nasal, and the aspirate; the term aspirate

being given to ph, th, and ch,

(1) The shut spirate consonants have three changes; viz., vocal, (aspirated)

nasal, and aspirate ; p into b, mh, and ph ; t into d, nh, and th ; and c

into g, ngh, and ch.

(2) Words beginning with the shut vocal consonants have two changes; viz.,

vocal and nasal; b is changed into / and m; d into dd and 7i; and g is

sometimes

omitted, and .sometimes changed into ng. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5537) (tudalen 025) (delwedd B5537) (tudalen 025)

|

WELSH LANQUAOB. 26

(3) Zl, rh, and m have each one change — vocal; It into I; rk into r; and m

into /.

70. Ch, s, Bi, /, and n, have no change; and the re- maining congonants are

never radical.

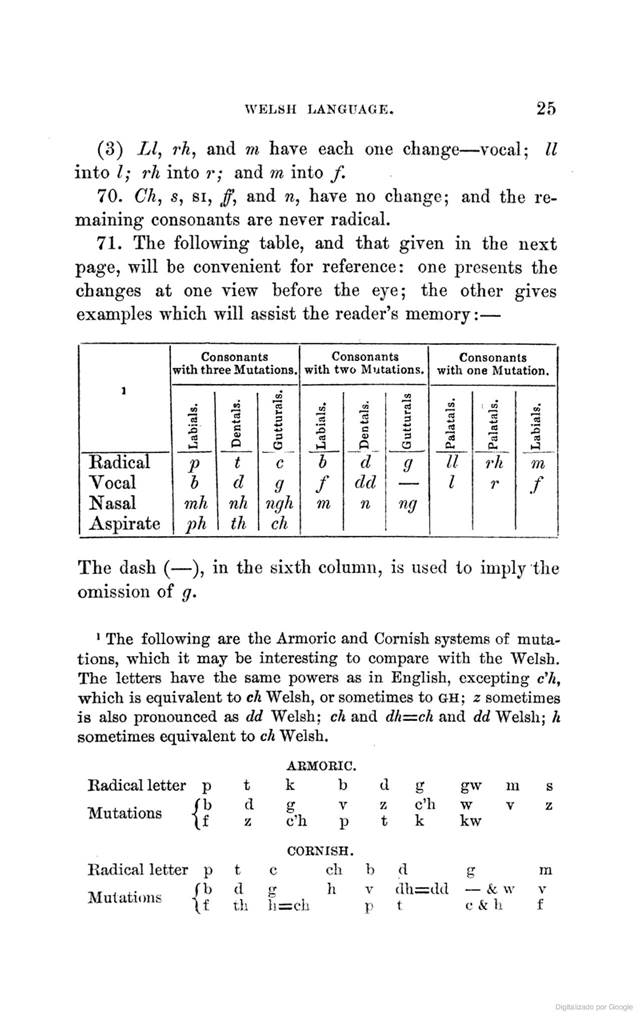

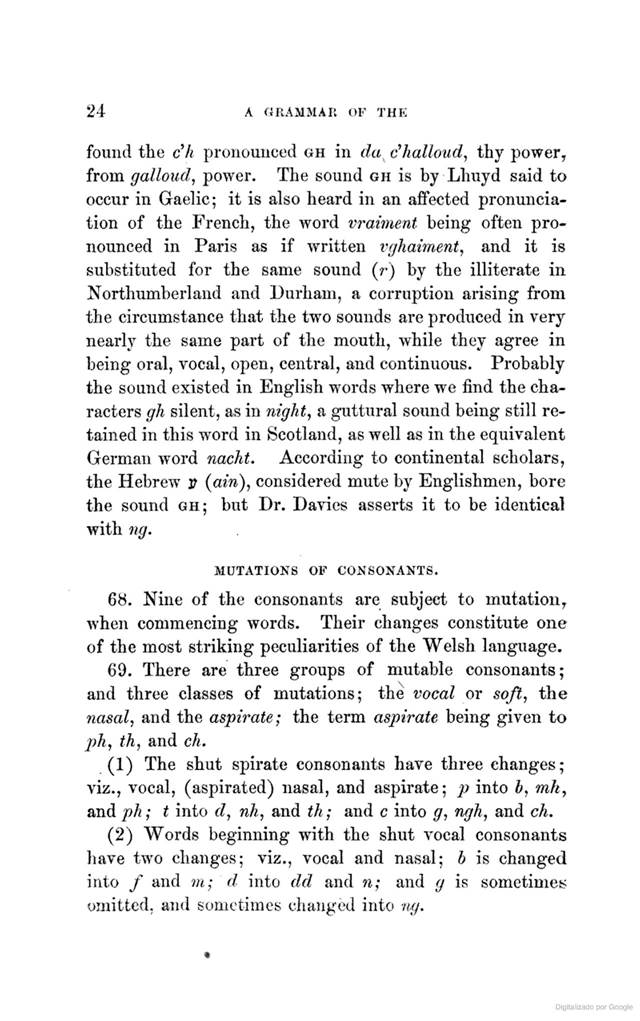

71. The follovfing table, and that given in the next page, will be convenient

for reference: one presents the changes at one view before the eye; the other

gives examples which will assist the reader's memory: — %% ■

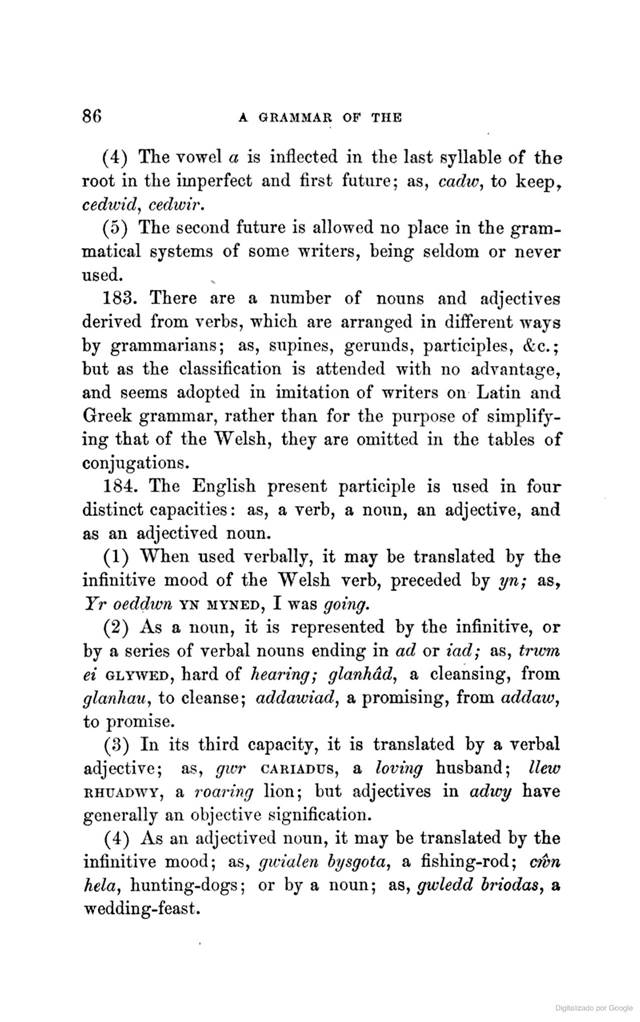

%%wll]lU°iceM”UtIsnB. %%”“'i”JTZou. %%««.':::•;■;»"„.. %%1 1 %%i

%%■i %%1 %%1 %%1 %%1 %%1 %%1

2 %%Hadicfll Vocal

Nasal Aspirate %%P

b

mh pk %%t d

nh th %%ch %%f %%dd %%"S %%' %%

f %% The dash ( — ), ia the sixth column, is used to imply the omission of g.

%% ' The (oEowing ate the Armoric and CorniBh syatemB of mnta- tiona, which

it may be interesting to compote with the Welsh. The letteta have the same

powets as in Eogliah, escopting c'A, which is eqaivalent to ch Weleb, or

sometimes to oh; z BOmctimea is also pTonooDced as dd Weleb; ch and dk=ch and

dd Welsh; h >B equivalent t« ch Welsh. %% Eadicat letter HutaHona %%

Badical letter Ma/aiiV'ns i %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5538) (tudalen 026) (delwedd B5538) (tudalen 026)

|

26 %% A GRAMMAR OP

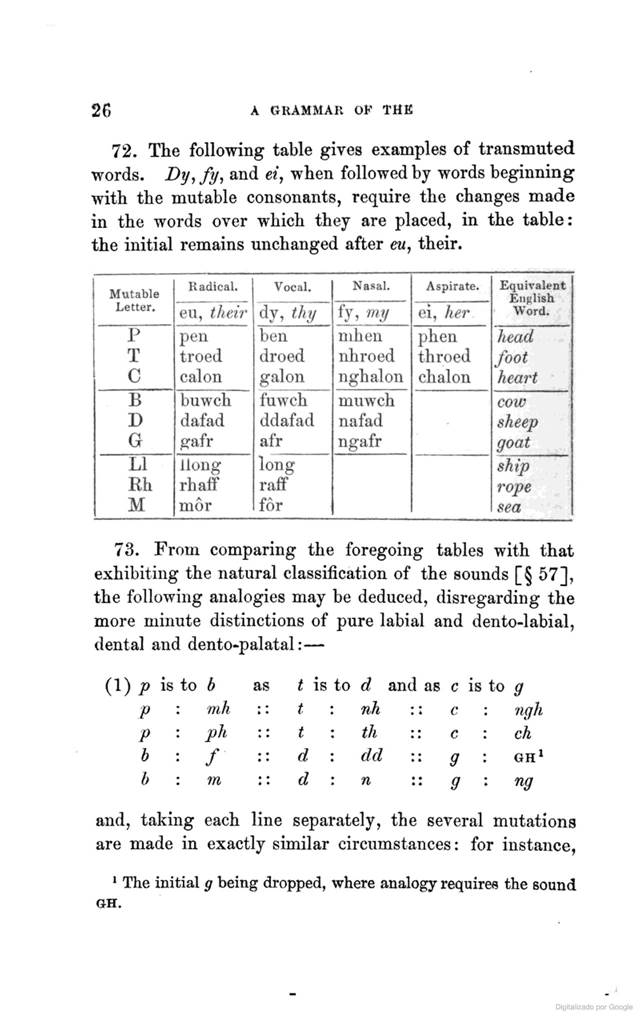

THE %% 72. The following table gives examples of transmuted words. Dy, fy”

and cz, when followed by words beginning with the mutable consonants, require

the changes made in the words over which they are placed, in the table: the

initial remains unchanged after ew, their. %% Mutable Letter. %%Radical.

%%Vocal. %%Nasal. %%Aspirate. %%Equiyalent

English

Word. %%eu, their %%dy, thy %%fj,my %%ei, her %%P

T C %%pen

troed

calon %%ben

droed

galon %%mhen

nhroed

nghalon %%phen

throed

chalon %%head

foot

heart %%B D G %%buwch

dafad

gafr %%fawch

ddafad

afr %%muwch

nafad

ngafr %%

cow

sheep

goat %%LI

Rh

M %%Hong rhaff mor %%long

raff

for %%%% ship rope sea %% 73. From comparing the foregoing tables with that

exhibiting the natural classification of the sounds [§57], the following

analogies may be deduced, disregarding the more minute distinctions of pure labial

and dento-labial, dental and dento-palatal : — %% (1) p is %%to b %%as %%t is

%%to %%d %%and as c is to “ %%p : %%mh %%

t : %%

nh %%:: c : ngh %%p : %%: ph %%

t %%

th %%:: c : ch %%b : %%■ f %%

d : %%

dd %%:: g : gh> %%b : %%: m %%

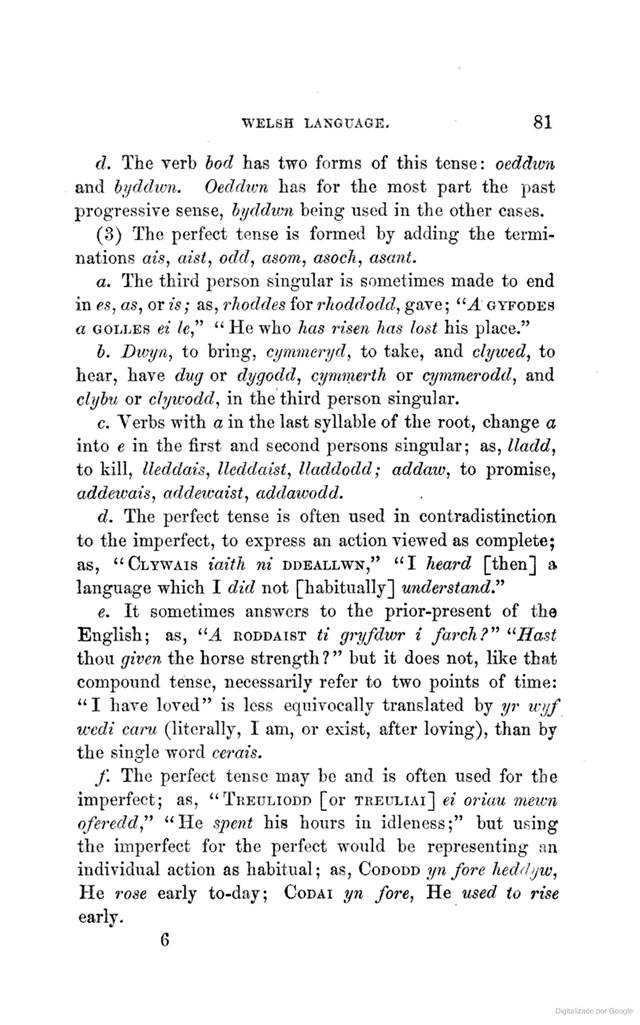

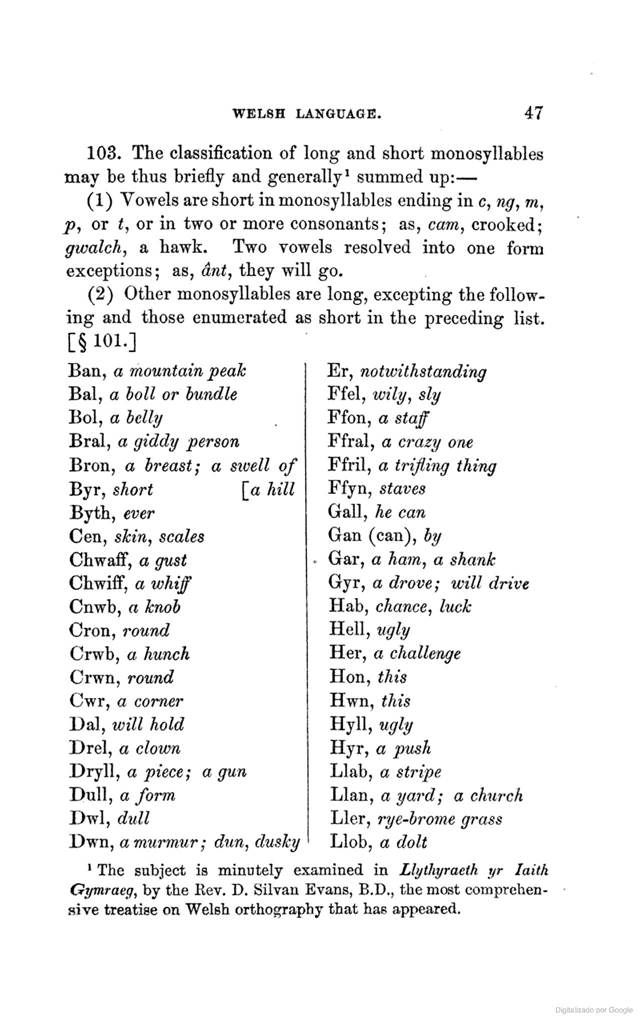

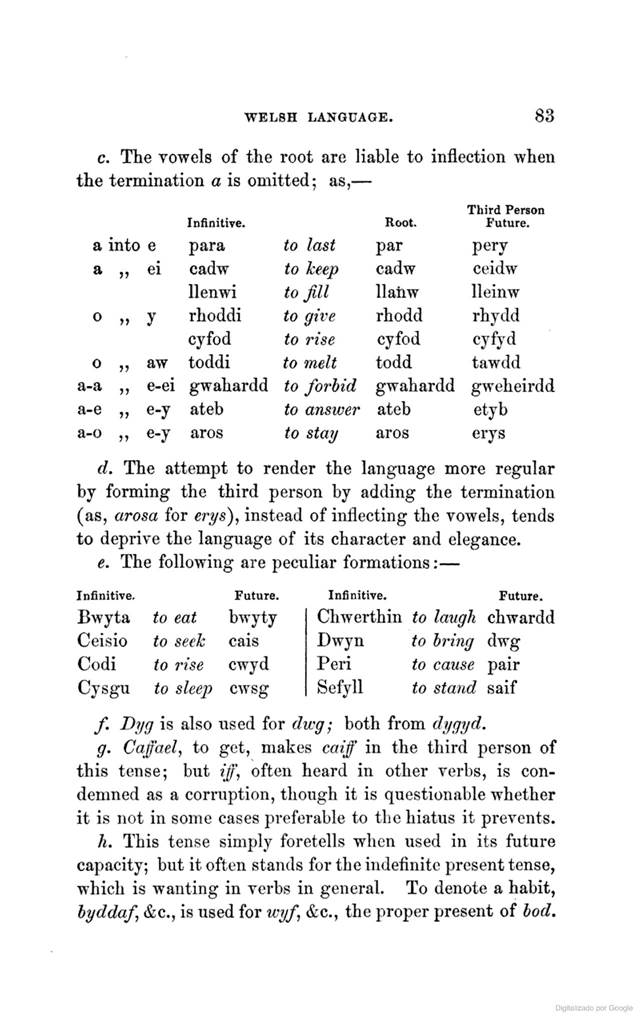

d %%

n %%:: g : ng %% and, taking each line separately, the several mutations are

made in exactly similar circumstances : for instance. %% * The initial g

being dropped, where analogy requires the sound %% aJT, %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5539) (tudalen 027) (delwedd B5539) (tudalen 027)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 27

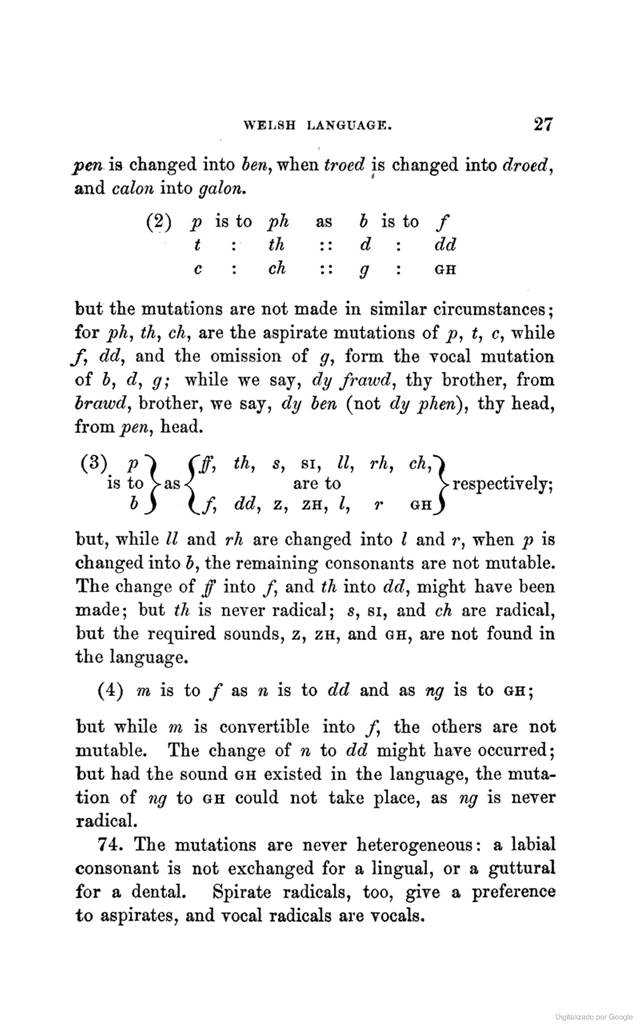

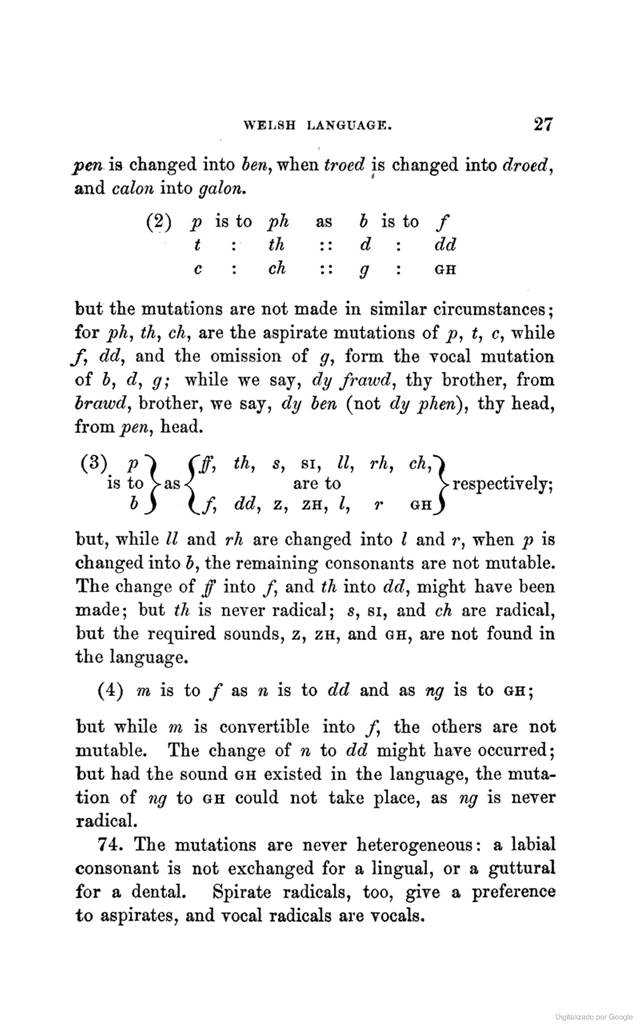

pen is changed into hen, when troed is changed into droed, and colon into

galon.

(2) “ is to ph as 5 is to / t : th :: d : dd c : ch :: g : gh

but the mutations are not made in similar circumstances ; for pky thy ch, are

the aspirate mutations of p, t, c, while f, dd, and the omission of g, form

the vocal mutation of b, d, g; while we say, dy frawd, thy brother, from

hrawd, brother, we say, dy hen (not dy phen), thy head, from”“, head.

(3) p1 r/j ““> «> SI, II, rh, ch,'“

is to > as < are to V respectively;

but, while ZZ and rh are changed into I and r, when j9 is changed into h, the

remaining consonants are not mutable. The change of ff into /, and th into

dd, might have been made; but th is never radical; s, si, and ch are radical,

but the required sounds, z, zh, and gh, are not found in the language.

(4) m IB to f B,B n 18 ix> dd and as «“ is to gh;

but while m is convertible into /, the others are not mutable. The change of

n to dd might have occurred; but had the sound gh existed in the language,

the muta- tion of ng to gh could not take place, as ng is never radical.

74. The mutations are never heterogeneous: a labial consonant is not

exchanged for a lingual, or a guttural for a dental. Spirate radicals, too,

g”““ «“ Y”“i”““sswy” to aspirates, and vocal radicals are “ocq”a. %% 28 %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5540) (tudalen 028) (delwedd B5540) (tudalen 028)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE %%

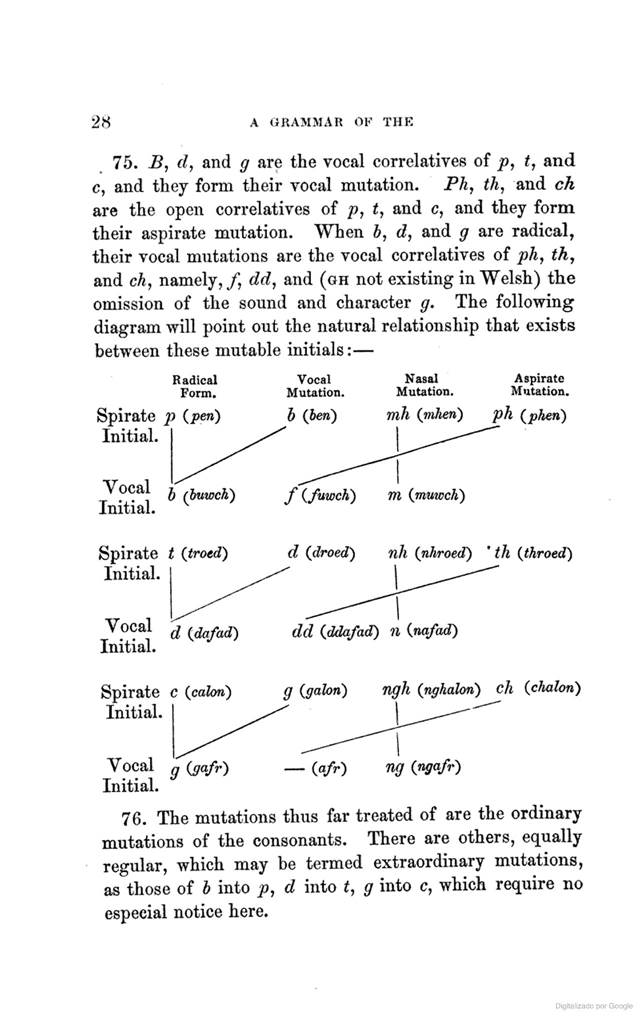

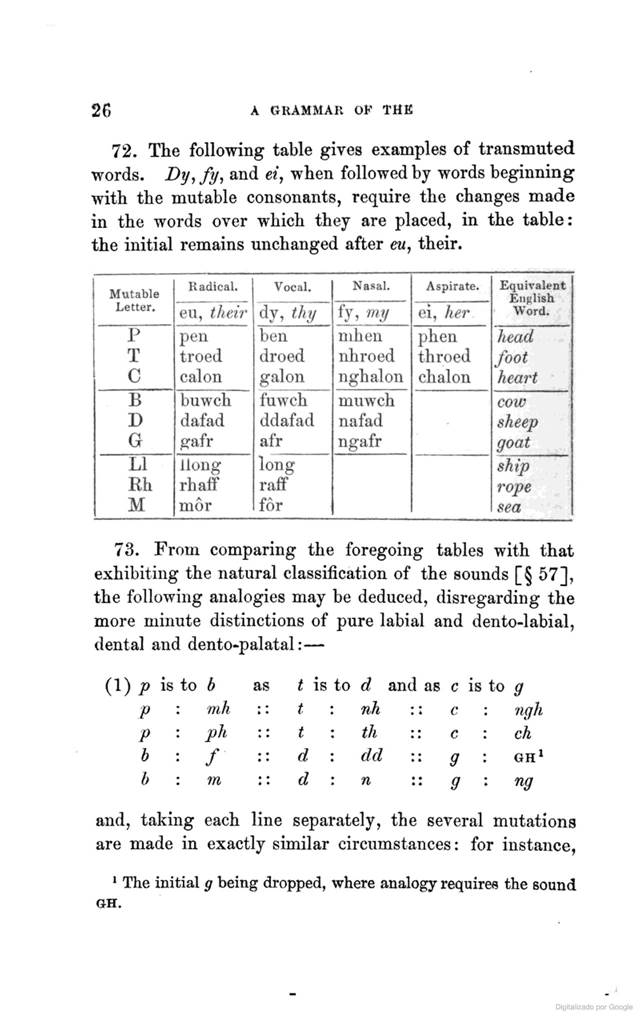

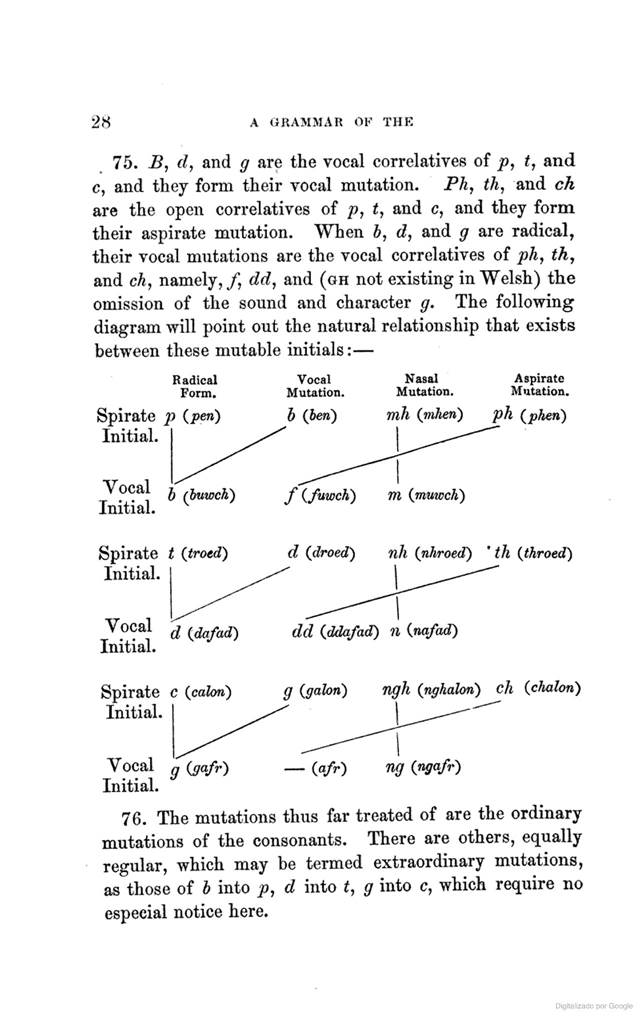

75. Bj d, and g are the vocal correlatives of “, f, and c, and they form

their vocal mutation. Ph, th, and ch are the open correlatives of p, t, and

c, and they form their aspirate mutation. When b, d, and g are radical, their

vocal mutations are the vocal correlatives of ph, th, and ch, namely, /, dd,

and (gh not existing in Welsh) the omission of the sound and character g. The

following diagram will point out the natural relationship that exists between

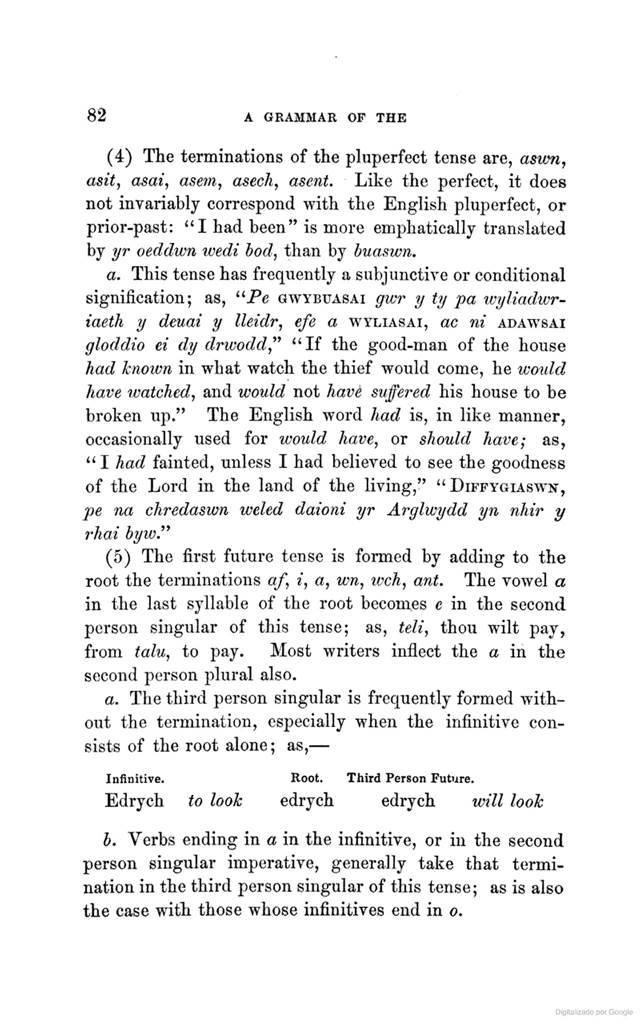

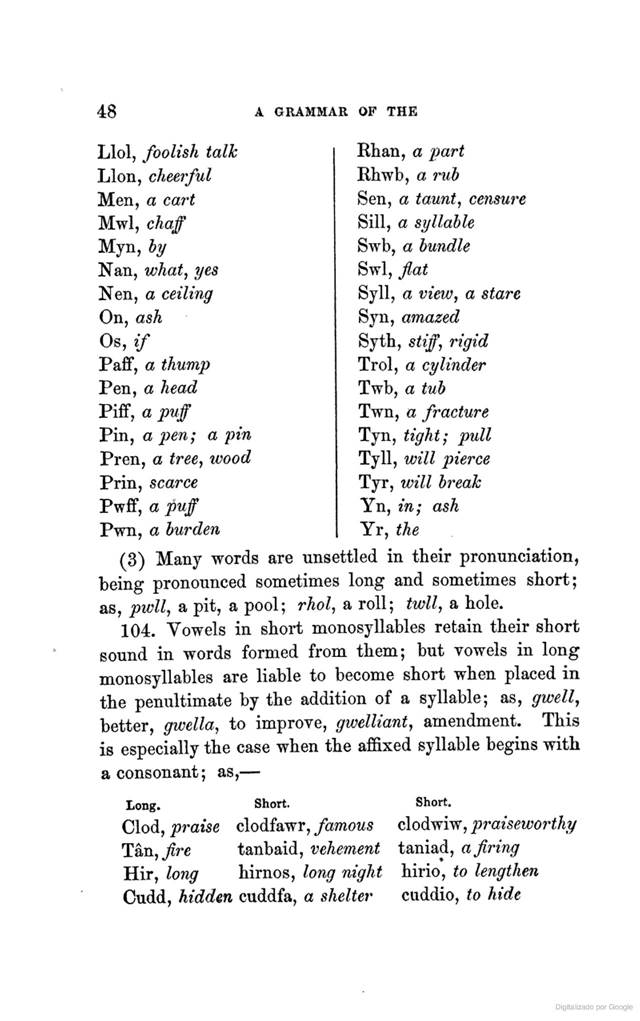

these mutable initials : — %% Radical Form. %% Spirate p {pen) Initial. %%

Vocal Mutation. %% Nasal Mutation. %% Aspirate Mutation. %% b (ben) mh (mhen)

ph {pken) %% Vocal J) “y”]”“ fifuwcK) m{muwcK) %% Spirate t (troed) Initial.

%% d {droed) nh (nkroed) th (Jhroed) %%

Vocal “ (““fad) dd iddafad) n inafad)

Initial. %% Spirate C (calon) g (galon) ngh (nghdlon) ch (chalon)

Initial. %% Vocal g {gafr) Initial. %%

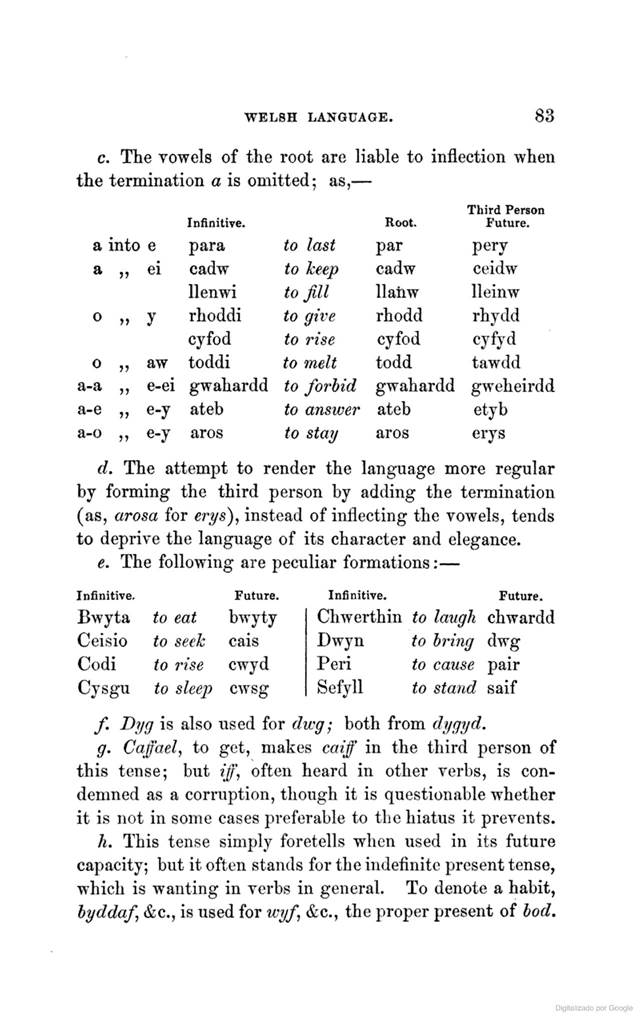

{afr) ng (ngafr) %% 76. The mutations thus far treated of are the ordinary

mutations of the consonants. There are others, equally

regular, which may be termed extraordinary mutations,

as those of b into p, d into t, g into c, which require no

especial notice here. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5541) (tudalen 029) (delwedd B5541) (tudalen 029)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 29

%% WOEDS. ACCENTUATION OF WOEDS.

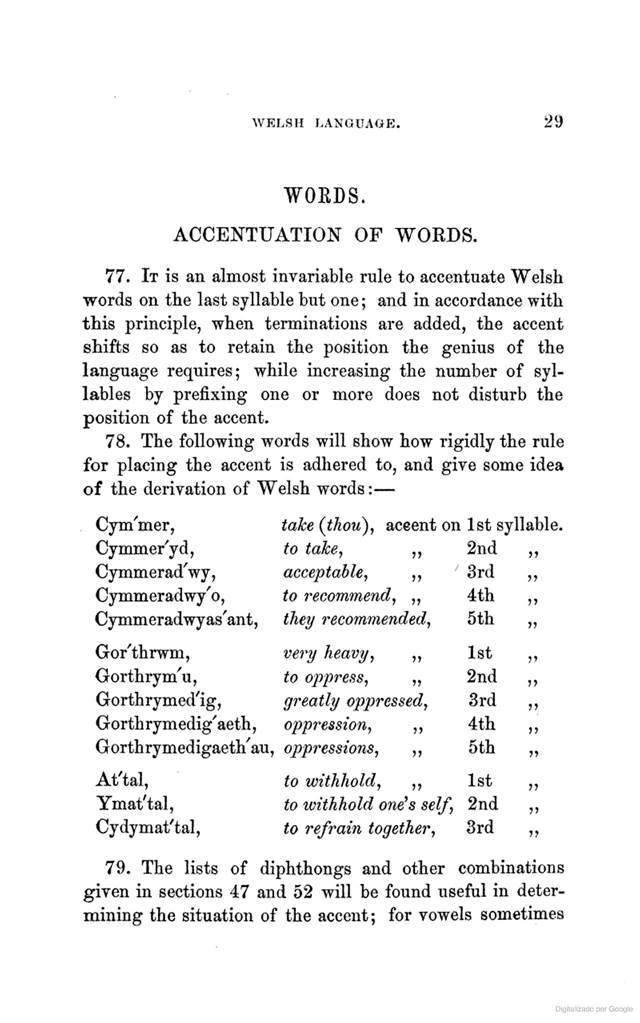

77. It is an almost invariable rule to accentuate Welsh words on the last

syllable but one ; and in accordance with this principle, when terminations

are added, the accent shifts so as to retain the position the genius of the

language requires; while increasing the number of syl- lables by prefixing

one or more does not disturb the position of the accent.

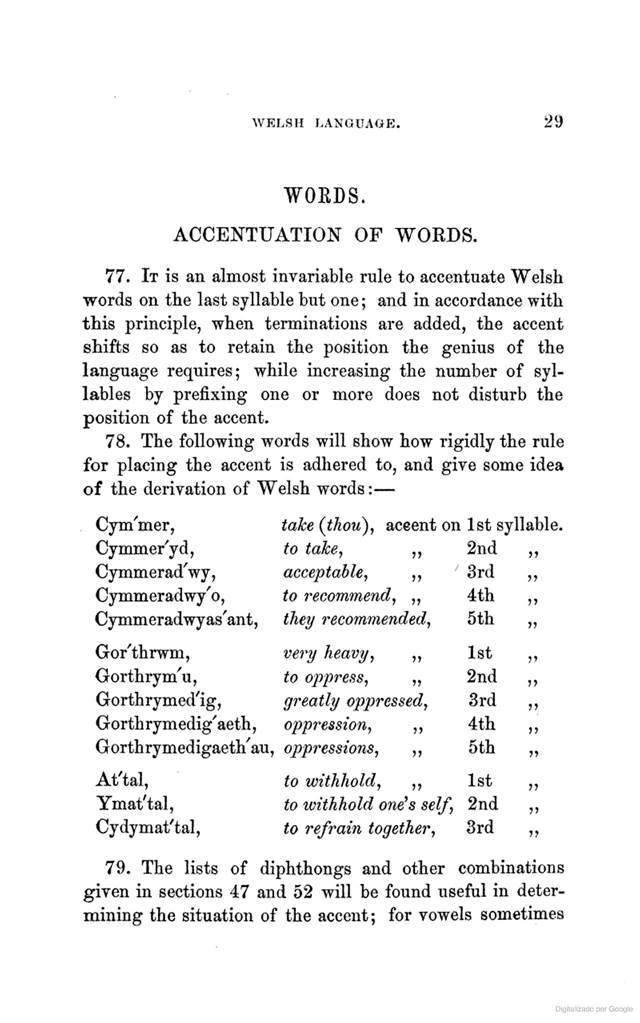

78. The following words will show how rigidly the rule for placing the accent

is adhered to, and give some idea of the derivation of Welsh words : — %%

Cym'mer, %%take (thou), accent oi %%I 1st 8 %%Cymmer'yd, %%to take, „ %%2nd

%%Cymmerad'wy, %%acceptable, „ %%3rd %%Cymmeradwy o, %%to recommend, „ %%4th

%%Cyrnrneradwyas ant, %%tket/ recommended, %%5th %%Gor thrwm, %%very heavy, „

%%1st %%Gorthrym u. %%to oppress, „ %%2nd %%Gorthrymed'ig, %%greatly

oppressed, %%3rd %%Gorthrymedig aeth. %%oppression, „ %%4:th

%%Gorthrymedigaeth au, %%, oppressions, „ %%5th %%At'tal, %%to withhold, „

%%1st %%Ymat'tal, %%to withhold one's self. %%2nd %%Cydymat'tal, %%to refrain

together, %%3rd %% 71 %% 79. The lists of diphthongs and other combinations

given in sections 47 and 52 will be fo\m.d\\!6»“i»N.SsiL ““'5t- miDing the

situation of the accent-, ioi -”o”““ “cs\s”'“““s£”““ %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5542) (tudalen 030) (delwedd B5542) (tudalen 030)

|

30 A aRAMMAR OF THK

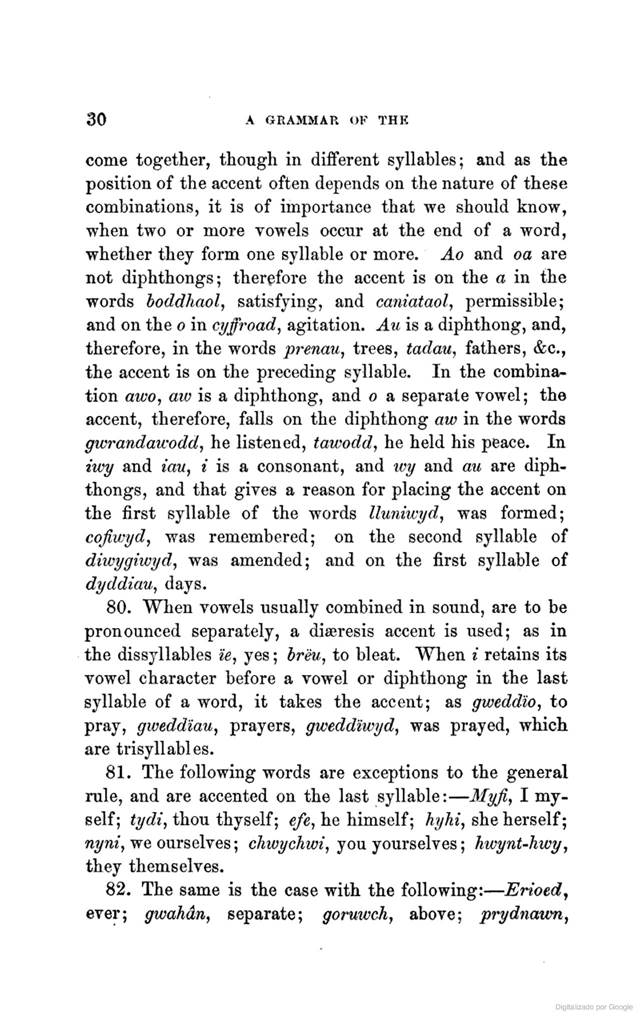

come together, though in different syllables; and as the position of the

accent often depends on the nature of these combinations, it is of importance

that we should know, when two or more vowels occur at the end of a word,

whether they form one syllable or more. Ao and oa are not diphthongs;

therefore the accent is on the a in the words hoddhaol” satisfying, and

caniataol, permissible; and on the o in cyffroad, agitation. Au is a

diphthong, and, therefore, in the words prenau, trees, tadau, fathers,

&c., the accent is on the preceding syllable. In the combina- tion awo,

aw is a diphthong, and o a separate vowel; the accent, therefore, falls on

the diphthong aw in the words gwrandawodd, he listened, tawodd, he held his

peace. In twy and iaUj i is a consonant, and wi/ and au are diph- thongs, and

that gives a reason for placing the accent on the first syllable of the words

lluniwyd, was formed; ccfiwyd, was remembered; on the second syllable of

dtwygiwyd, was amended; and on the first syllable of dyddiau, days.

80. When vowels usually combined in sound, are to be pronounced separately, a

diseresis accent is used; as in the dissyllables ze, yes ; breu, to bleat.

When t retains its vowel character before a vowel or diphthong in the last

syllable of a word, it takes the accent; as gweddw, to pray, gweddiau,

prayers, gweddtwyd” was prayed, which are trisyllables.

81. The following words are exceptions to the general rule, and are accented

on the last syllable: — Myfi” I my- self; tydi” thou thyself; e/e, he

himself; hyhi, she herself; nynij we ourselves ; chwychwiy you yourselves ;

hwynUhwy, they themselves.

S2, The Bame is the case with the following: — Erioed” ever; “TvaAdn,

separate ; goruwchy aSbo”e-, pryduawa” %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5543) (tudalen 031) (delwedd B5543) (tudalen 031)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 31

evening; trache/n, again; ychwaith” neither; yshonc” a jerk; ystol” a stool;

ystwCy a pail; ystwr” noise; ystor, a store; a circumflex accent being often

used when the vowel is long. The y in the last six words, and a few like

them, is often dropped.

83. Dissyllables formed with the prefixes cy, cyf, di, ym, are irregular; as,

cyh”d, as long; cyfuwch, as high; didranCy endless; dtddadl, without dispute;

difliriy un- tiring; dinerth, impotent; dioed, without delay; diwerth,

worthless; ymddy leave; ymguddy hide; ymlddd, to kill one's self; ymwely

visit; and other verbs in the future or imperative.

84. The prepositional and adverbial phrases ger bron, before, ger Haw, at

hand, heb laWy besides, rhag Haw, henceforth, oddt wrthy from, oddi mevm,

within, oddi- drawy from, o gylchy around, uwch ben, overhead, uwch lawj

above, are often written as dissyllables, in which case they are accented on

the last syllable. They are, however, better written as separate words.

85. Dissyllabic compounds of yUy when written thus, ynghydy together, ymhob,

in all, ymron, almost, are exceptions to the general rule; but they also are

better written as two words, yng nghydy ym mkoby ym mron.

86. TmherawdwTy emperor, iachawdwvy saviour, when written ymherawdvy

iachaiodvy are accented on the last syllable.

87. The situation of the accent in words in au and ad is often indicated by

the letter A, or by a diaeresis or a circumflex accent ; as, mwijnhauy to

enjoy; mtvynkddy enjoy- ment; nesdUy to approach; nacddy refusal. [§96 (8).]

In these terminations, two letters a are resolved into one; the formation

being mwynha-aUy mwt/nha-ad, uesa-au” uaA!.a-oA.. Homo writers use both the

accent and tV<i\feXX.”'c K” •ase”'wsv” %% 32

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5544) (tudalen 032) (delwedd B5544) (tudalen 032)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

syllables beginning with h are not always accented; for example, deheu,

south, ammheu, doubt, anhawdd, difficult."

88. In words ending in o?, the accent is not necessary, as they are all

accented on the last syllable; as, crynoi or crynholy to collect. Many of

these, however, have no aspiration; as, ymdroi, to turn one's self, osgoi, to

turn aside, goloi, to envelope. The termination oi is often pronounced as two

syllables; for this reason it is often written with a diasresis accent; thus,

ymdroi, in which case the accent is regular. In gwrandewch (gwrandaw-wch),

hear you, gadewch (gadaw-wch), leave you, and the like, the accent is sometimes

omitted, but the letter h cannot be inserted.

89. Names of towns, villages, farms, and other descrip- • tive proper names,

present frequent exceptions, which are

accented as if the words comprising them were written separately; as,

Caergrawnt, the town on the Granta (Cambridge); Caerllur, Llur*s town

(Leicester); Aber- gwaen, the mouth of the Gwaen (Fishguard); Penybont, the

end of the bridge (Bridgend); Nantyglo, coal-brook; Llwynteg, fair grove;

Mynyddmawr, great mountain; Cvmidu, black dingle; Neuaddwen, white hall.

Words of this kind are often (and, when not opposed to general usage, better)

written as separate words.

90. Words having w as the only vowel in the penultima present occasional

exceptions to the general rule; as, meddwdod, drunkenness; marumad, an

clegj-, chwerwder, bitterness; gwaewffon, a spear; which are accented on the

first syllable. Some of them frequently suffer elision of the w, in which

case the accentuation is regular.

91. Custom has fixed the accent on the first syllable of Saesonae(/j

Seisoneg, Seisonig, English, which arc hence

often written Saesncg, Seisneg, Seisnig, %% WELSH LANaUAQB. %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5545) (tudalen 033) (delwedd B5545) (tudalen 033)

|

33 %% THE SPELLING

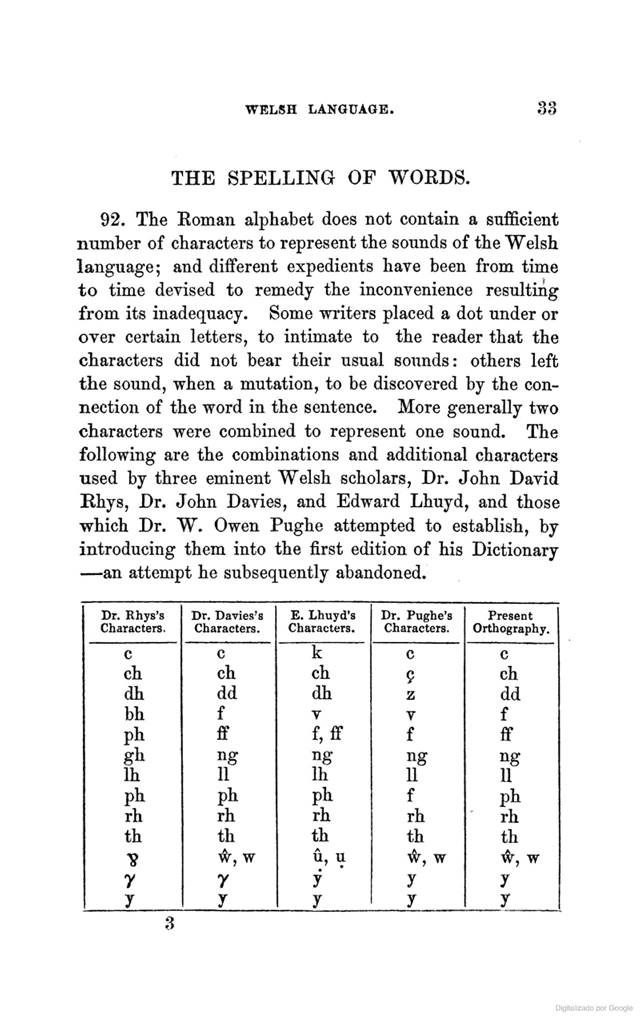

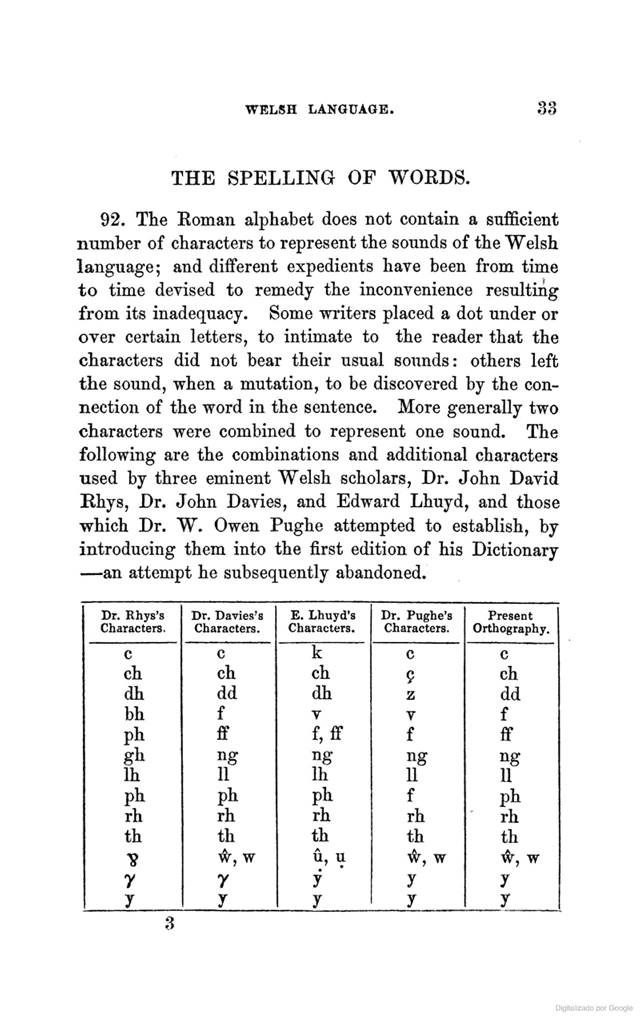

OF WORDS. %% 92. The Eoman alphabet does not contain a sufficient number of

characters to represent the sounds of the Welsh language; and different

expedients have been from time to time devised to remedy the inconvenience

resulting from its inadequacy. Some writers placed a dot under or over

certain letters, to intimate to the reader that the characters did not bear

their usual soxmds: others left the sound, when a mutation, to be discovered

by the con- nection of the word in the sentence. More generally two characters

were combined to represent one sound. The following are the combinations and

additional characters used by three eminent Welsh scholars, Dr. John David

Rhys, Dr. John Davies, and Edward Lhuyd, and those which Dr. W. Owen Pughe

attempted to establish, by introducing them into the first edition of his

Dictionary — an attempt he subsequently abandoned. %% Dr. Rhys's Characters.

%%Dr. Davies's Characters. %%E. Lhuyd's Characters. %%Dr. Pughe's Characters.

%%Present Orthography. %%c %%C %%k %%C %%C %%ch %%ch %%ch %%9 %%ch %%dh %%dd

%%dh %%z %%dd %%bh %%f %%V %%V %%f %%ph %%ff %%f, ff %%f %%ff %%Ih %%»g 11

%%Ih %%ng 11 %%ng 11 %%ph rh %%ph

rh %%ph

rh %%f rh %%ph

rh %%th %%th %%th %%th %%th %%1? %%”, w %%ii, u %%”, w %%”, w %%r %%” i %%J

%%y

1 %%\ \ %%7 1 %%7 1 %%7 %% 34

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5546) (tudalen 034) (delwedd B5546) (tudalen 034)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

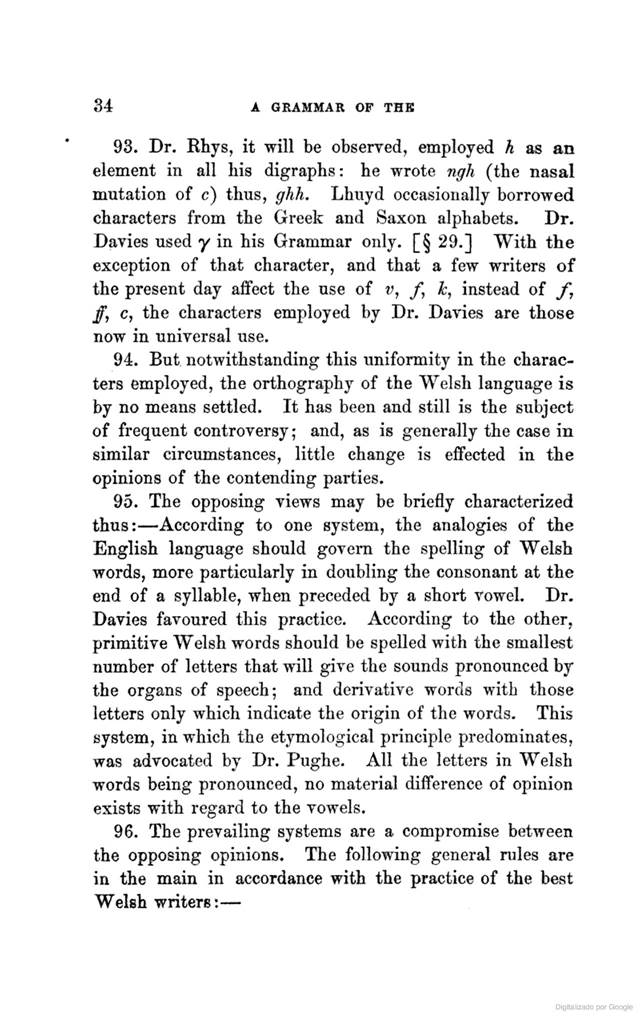

93. Dr. Khys, it will be observed, employed A as an element in all his

digraphs: he wrote ngJi (the nasal mutation of c) thus, ghh. Lhuyd

occasionally borrowed characters from the Greek and Saxon alphabets. Dr.

Davies used y in his Grammar only. [§ 29.] With the exception of that

character, and that a few writers of the present day affect the use of v, /, h,

instead of f, ffy c, the characters employed by Dr. Davies are those now in

universal use.

94. But notwithstanding this uniformity in the charac- ters employed, the

orthography of the Welsh language is by no means settled. It has been and

still is the subject of frequent controversy ; and, as is generally the case

in similar circumstances, little change is effected in the opinions of the

contending parties.

• 95. The opposing views may be briefly characterized thus: — According to

one system, the analogies of the English language should govern the spelling

of Welsh words, more particularly in doubling the consonant at the end of a

syllable, when preceded by a short vowel. Dr. Davies favoured this practice.

According to the other, primitive Welsh words should be spelled with the

smallest number of letters that will give the sounds pronounced by the organs

of speech; and derivative words with those letters only which indicate the

origin of the words. This system, in which the etymological principle predominates,

was advocated by Dr. Pughe. All the letters in Welsh words being pronounced,

no material difference of opinion exists with regard to the vowels.

96. The prevailing systems are a compromise between the opposing opinions.

The following general rules are in the main in accordance with the practice

of the best Welsh writers: — %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5547) (tudalen 035) (delwedd B5547) (tudalen 035)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 35

(1) Double consonants are nerer used in words of one syllable; as, earn,

crooked; rAaw, apart; s”“A, stiff; cwt, a tail; hyr, short; hyll, hideous;

pwff, a puff; llong, a ship ; mellt, lightning. LI, ff, ng, and the other

digraphs [§31], be it remembered, are considered single letters in Welsh.

(2) Two consonants are not inserted when they are not found in the members of

which the words are com- posed; as, anesmtvythj uneasy, from the negative

prefix an and esmioi/th, easy; hysedd, fingers, from hys, a finger, and the

termination edd : not annesmwyth and hyssedd,

a. The use of double letters to indicate a preceding short vowel is unsuited

to the Welsh alphabet, and cannot be adopted without leading into

inconsistency. While some letters might be doubled without inconvenience, as

f», w, <, p” r, c, in cam, a step, tynu, to pull, ateh” to answer, tipyn”

a little bit, tori, to cut, tecaf, fairest; others, as mvmg, a mane, sychu,

to dry, toddi, to melt, cqfio, to remember, cefyl, a horse, calon, a heart,

allor, an altar, could not, for obvious reasons, be written mvmgng, syckchu,

toddddi, cojffio, ceffffyl, callon, allllor,

(3) When, however, the same consonant occurs at the end of one syllable and

at the beginning of the next, it is retained in both syllables of the

compound word; as, pennod, a chapter, from pen, a head, and nod, a note;

annaturiol, unnatural, from an and naturiol, natural; mammaeth, a nurse, from

mam, a mother, and maeth, nur- ture.

a. Words having the termination -rwydd, and some others, furnish occasional

exceptions; as, sicrwydd, cer- tainty, from sicr, sure.

(4) In such words as pummed” “itla. (“tctccl -pumi”“ cannoedd, hnndredB (from

cant)” chwmnyfiku” \” “«sa” %% 36

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5548) (tudalen 036) (delwedd B5548) (tudalen 036)

|

A GRAMMAR OF THE

(from chwant), annoeth, unwise (an”doeth), dattodj to loosen {dad'dod)j the

consonants should be repeated, as they represent those found in the words

from which they are derived, having undergone a change in accordance with the

idiom of the Welsh language: the p, t, and d are not omitted, but changed

into w, w, and t.

a. It is not usual to retain mm or nn before a conso- nant, as they give the

word an uncouth appearance; as canfedy hundredth; pumwaith, five times; not

cannfedy pummwaith.

h. In cases analagous to that of chiuennt/ck, pummedy nc becomes ng (not nng

or ngng)\ as, trengu, to expire (from tranc).

(5) In the euphonic changes of the negative prefix an into am and ang, the m

is retained, but the ng is dis- carded; as, ammrwd, unheated (an-brwd);

ammharod, . imready (an-parod) ; anghyfiawn, unjust {an-cyfiavm) ; not angnghyfiawn”

which is unsightly, nor annghyfiavmy which is opposed to euphony and usage.

(6) In the case of the prefixes cym” cyn” cys, cyt, V synonymous with cyd or

cy, the consonant is repeated

before m (not mk), n (not wA), s, and t; as, cymmrawd {cym-hrawd, a brother),

a consociate; cymmaint (maint, size), of equal size; cynnifer, as many

{nifer, number); cyssylwedd, joint substance; cytteimlo, to sympathize. But

cy is preferable before mh, nh, ng, ngk, th, and f; as, cymhivys, suitable;

cynhiurf, a disturbance; cyngelyn, a mutual enemy; cynghanedd, consonance;

cythi*wjl, dis- turbance; cyfrad, conspiracy. In all these, the omission of

one consonant seems to be a matter of convenience; the construction of

cyfrad, for instance, being probably cyd'drad, c”m”mrad, cyd”frad” or

cyf-frad, cyfrad, one f being omitted to avoid the Bound jf: Vn. '““ mvssaKt”

%%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5549) (tudalen 037) (delwedd B5549) (tudalen 037)

|

WELSH LANGUAGE. 37

cyd-ganedd” cyng-nghanedd, cynghanedd; cyd-pwys” cym- tnhwys.

a. For the sake of distinction, n is retained in the prefix cyn, before, when

preceding another n; as, cynnhorf, van; cynnhrigolion, ahorigmes -,

cynnrychiol, "present,

(7) The preposition yn, in, is changeable into ym and yng; and is properly

written as a separate word; as, yng nghanol nos, in the middle of the night;

ym mhen awr” in an hour's time. The forms yn nghanol” yn mhen, are

objectionable as uneuphonious and opposed to general usage; the forms y”mhen,

ynghylch, as creating unne- cessary exceptions to the general rule of

accentuation.

(8) The insertion of the letter h in some words ending in au and dd, as

mwynhau, to enjoy, and mwynhdd, enjoy- ment, is, as has been before observed,

a matter of dispute. Perhaps the most judicious way of spelling these words

would be to insert the h when not preceded by a spirate consonant [§55 (4)],

as the circumflex accent does not suggest the idea of the aspiration which

exists in the ter- mination. In llyfnhau, to smooth, cwblhau, to fulfil, mwy-

hauj to augment, the h is heard and should be inserted. In caniatdUj to

grant, gwelldu, to improve, gwarthdu, to asperse, llesdu, to benefit, nacdu,

to refuse, the accent alone is sufficient, there being no appreciable

aspiration in addition to that of the spirate consonant t, U, th, s, or Cy

which as it were propels the final syllable; but there does not appear to be

any reason for doubling any of those letters, as the same consonant ends one

syllable and begins the other. Sometimes the vocal consonant co- alesces with

the h, and its spirate correlative is the result; as in coffdu, to

commemorate, from cof, memory, in which the h would be superfluous. On t\iG

«>2cmfe “tvbl”y"“““ c; should be snbBtitnted for the g in t”e n”ot”

l\e%gau” V” %%

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B5550) (tudalen 038) (delwedd B5550) (tudalen 038)

|

38 A GRAMMAR OP THE

debilitate : the introduction of h into the word would be objectionable, as

the vocal sound g cannot be retained between a and h; but llesgdu is the

settled form. In parhau, to continue, byrhau, to shorten, sicrhau, to make

sure, and the like, it should be recollected that r and h represent two

sounds, the vocal r and the aspirate h, and have not the simple spirate sound

of rh in rhariy a part. [§64.] It would be useful, but it is not usual, to

separate them with a hyphen, for the sake of distinction, as is done for the

same reason in ufudd-dod” obedience; hwynUhwy” they themselves.

(9) The words angeuol or angheuolj deadly, eangder or ehangder, spaciousness,

brenines or brenhinesj a queen, cenedlaeth or cenhedlaeth, a generation,

boneddig or bon- heddig, noble, synwyrau or synhtvyrau, senses, diarebion or

diarhebion, proverbs, and the like, are of unfixed orthography. The

aspiration is not heard in the words from which they are inmiediately formed;

angeu, death; eang, spacious; brenin, a king; cenedl, a nation; bonedd,

nobility; synwyr, sense; diareb, a proverb; but it is introduced with the

accent, when one syllable is added. The addition of another syllable removes

the accent, and the aspiration is again lost; as, boneddigaidd, noble;

cenedlaethaUf generations ; boneddigion, gentlemen. Some writers discard the

h in all these words ; others insert it even when not heard in the spoken word;

and others, taking a middle course, use it only when the syllable is

accented. The most convenient course is to omit it.

97. U and i are frequently substituted one for the

other, as terminations of verbs in the infinitive mood.

To avoid error in this particular, it should be known,

i;hat when w is the last letter but one, as in ervwtj to

name, or when o occurs in the last «»“\!L«Jo\e Wt one” %%

|

|

|

|

|

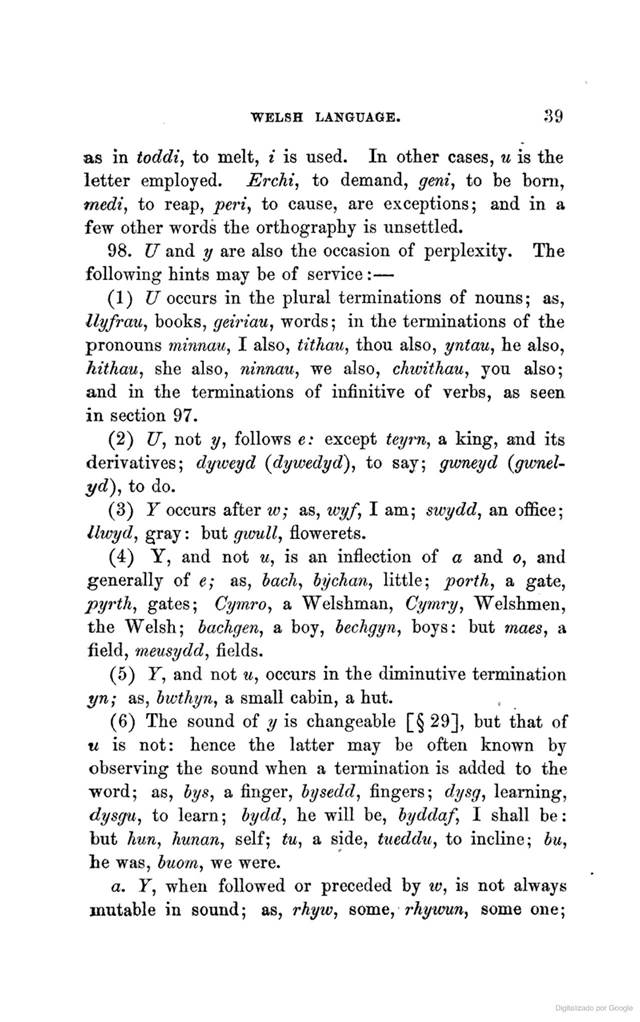

(delwedd B5551) (tudalen 039) (delwedd B5551) (tudalen 039)

|

WELSH LANQUAQE. 39

as in toddtj to melt, i is used. In other cases, u is the letter employed.

Erchi, to demand, geni” to be bom, medi” to reap, peri” to cause, are

exceptions; and in a few other words the orthography is unsettled.

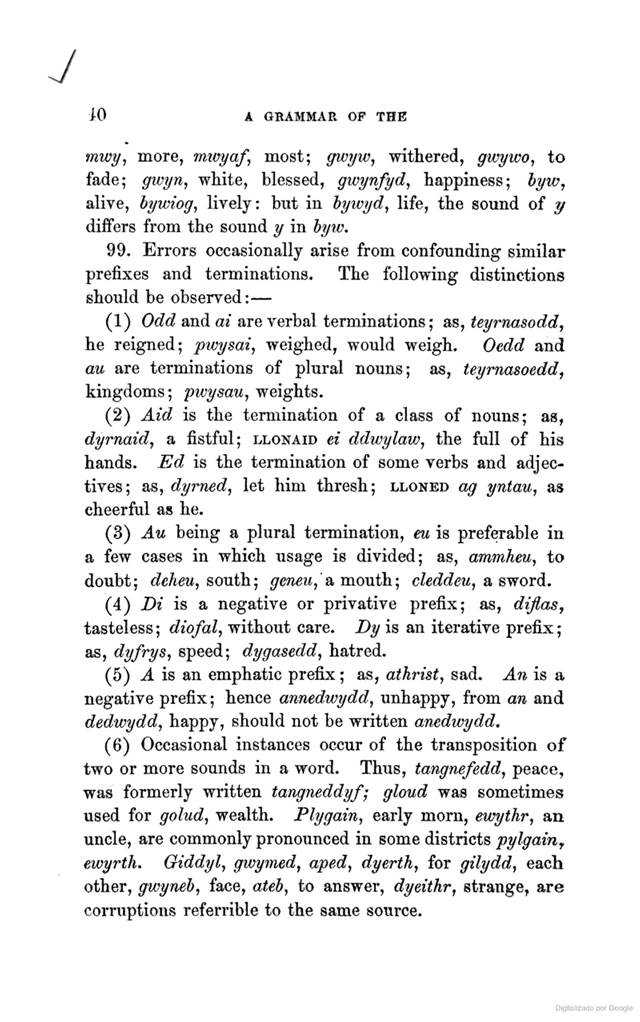

98. U and y are also the occasion of perplexity. The following hints may be

of service : —

(1) CT" occurs in the plural terminations of nouns; as, llyfrauy books,

geiriau” words ; in the terminations of the pronouns minnau, I also, tithau,

thou also, yntaUj he also, hithau, she also, ninnau, we also, chwitkau” you

also; and in the terminations of infinitive of verbs, as seen in section 97.

(2) U, not y, follows e: except teyrn, a king, and its derivatives; dyweyd

{dywedyd), to say; gumeyd (gumel- yd), to do.

(3) T occurs after w; as, wyf, I am; swydd, an office; llwyd, gray : but

gwull, flowerets.

(4) Y, and not w, is an inflection of a and o, and generally of e; as, bach,

bychan, little; porth, a gate, pyrthj gates; Cymro, a Welshman, Cymry,

Welshmen, the Welsh; bachgen, a boy, bechgyn, boys: but maes, a field,

meusydd, fields.

(6) Y, and not u, occurs in the diminutive termination yn; as, bwthyn, a

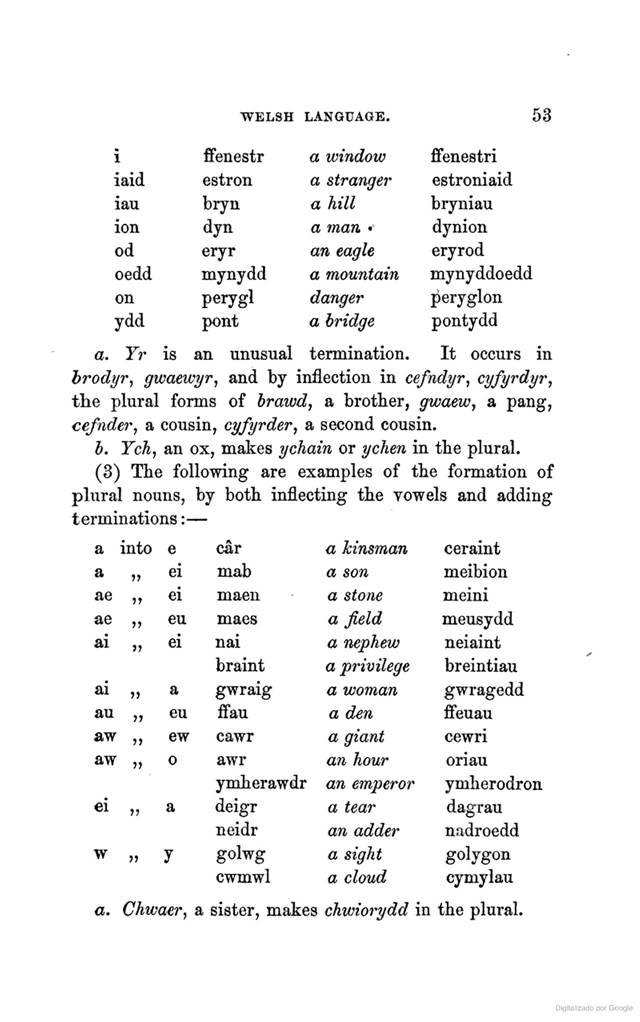

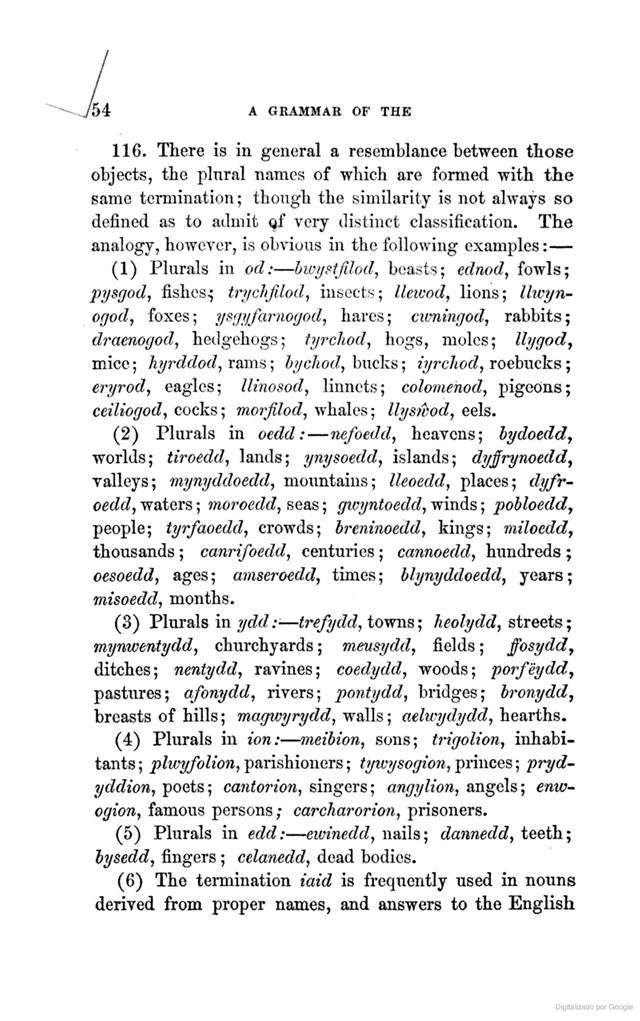

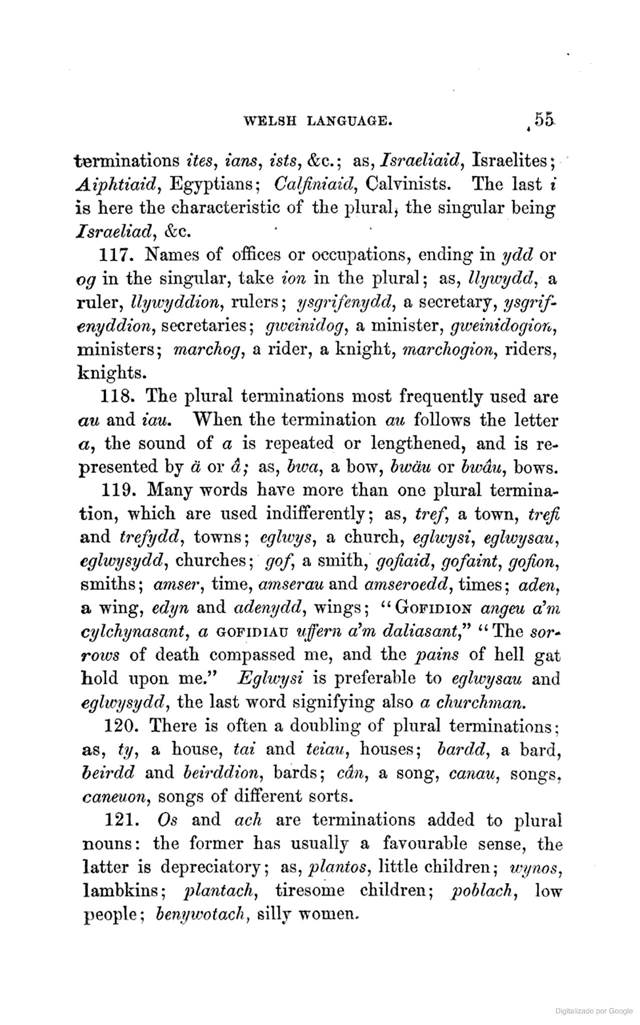

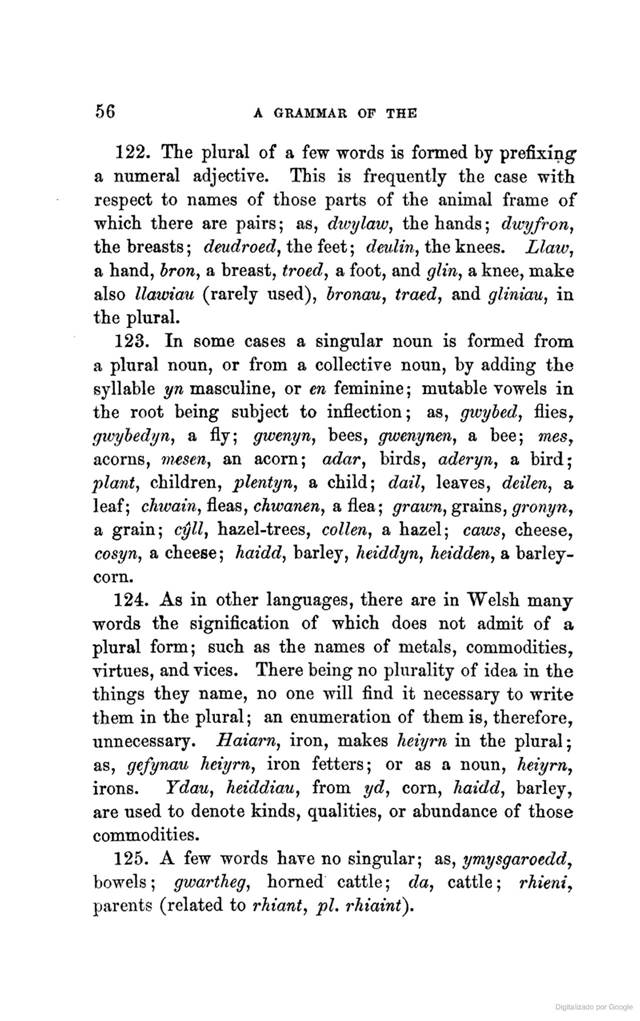

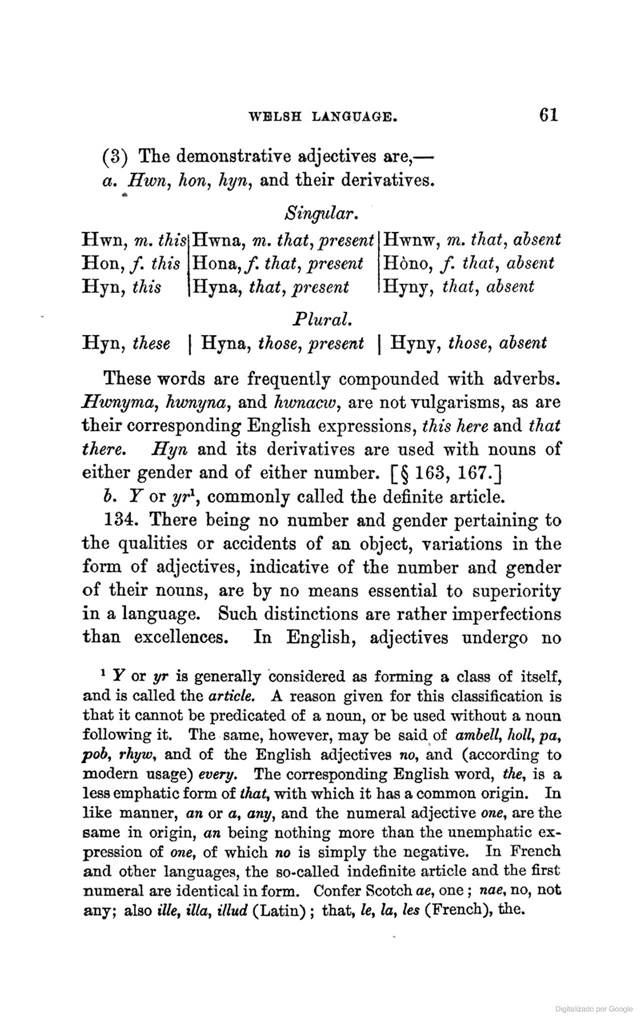

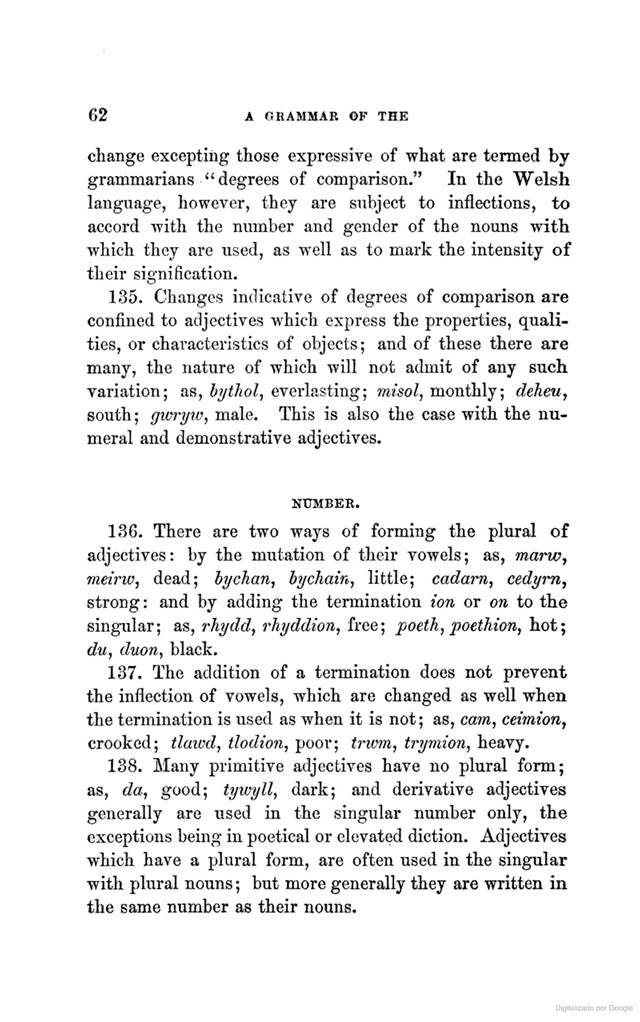

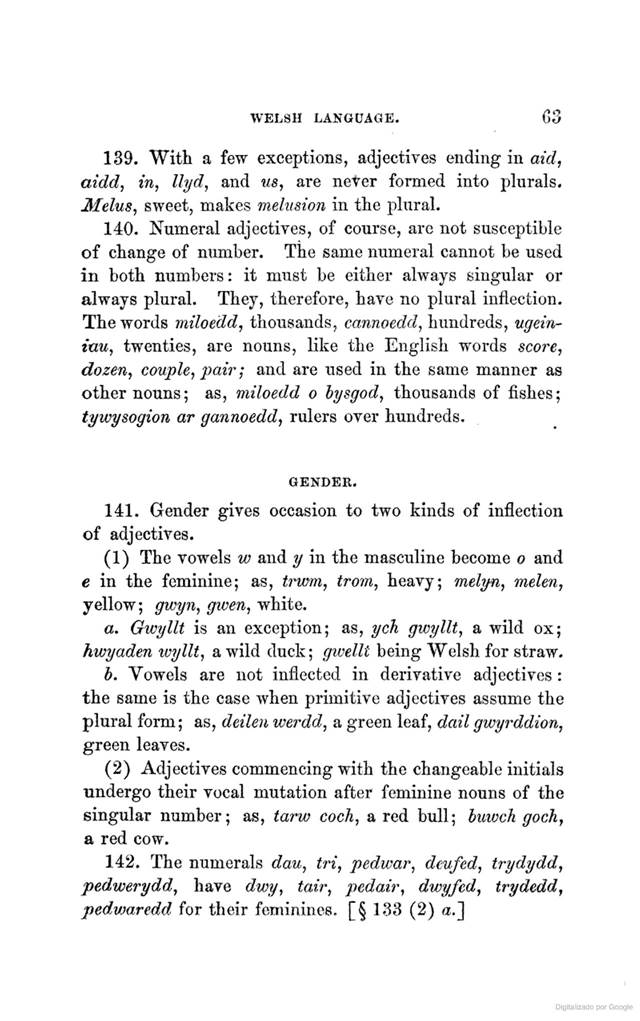

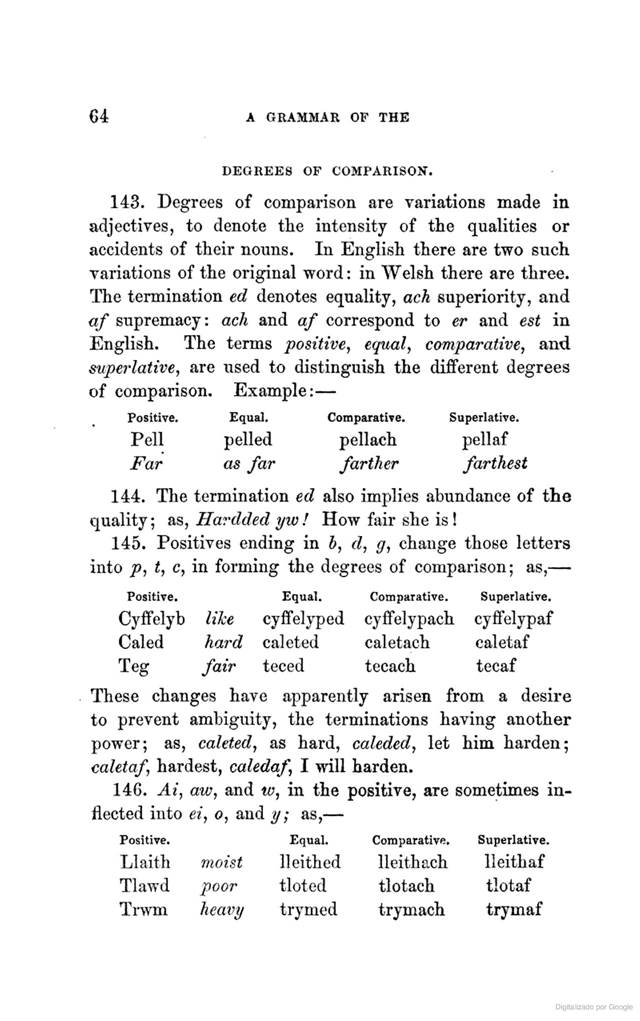

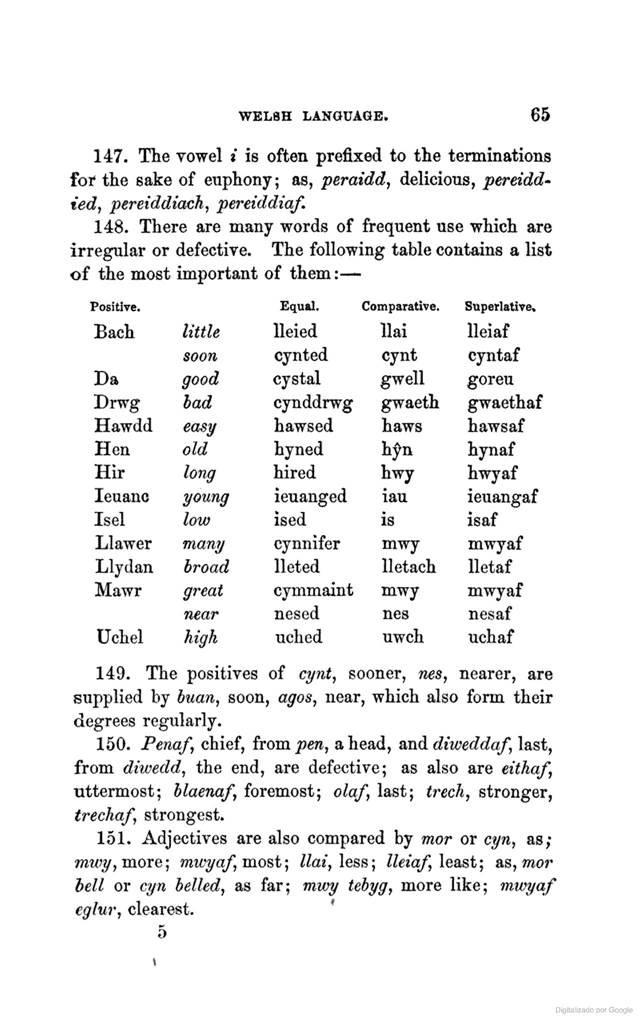

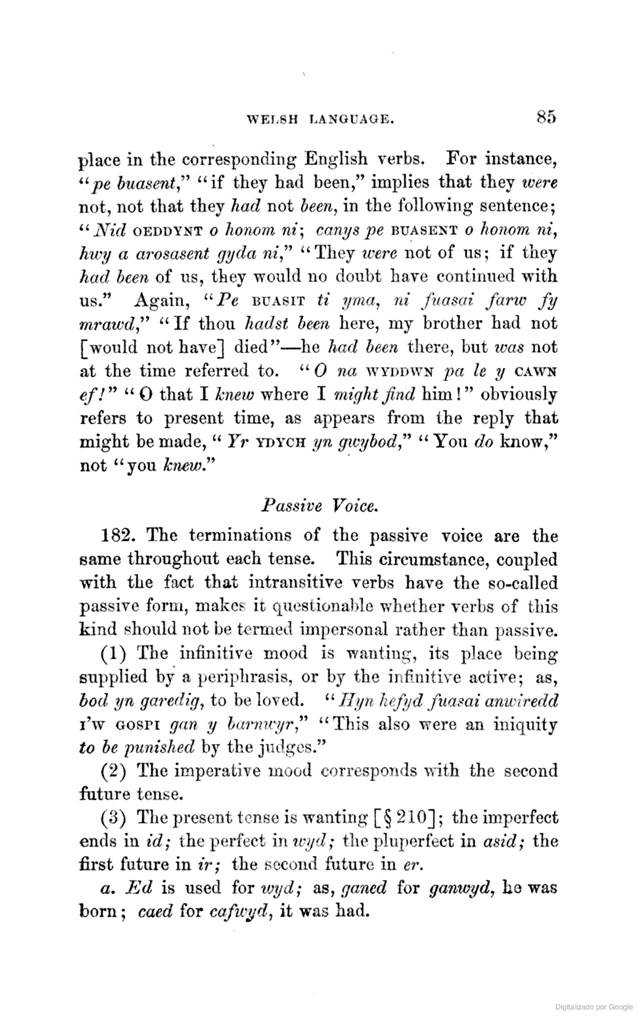

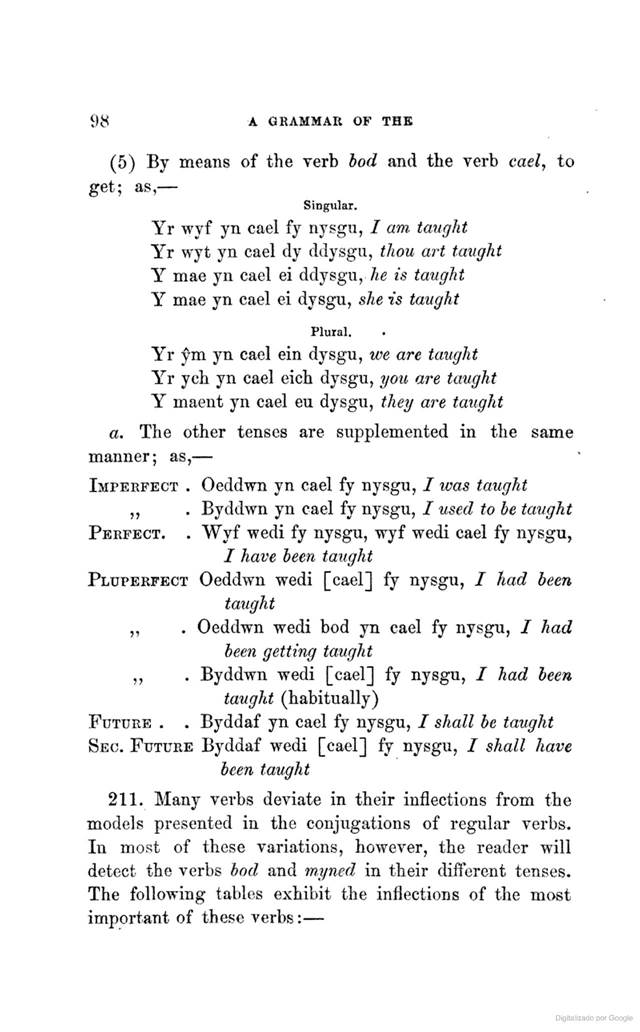

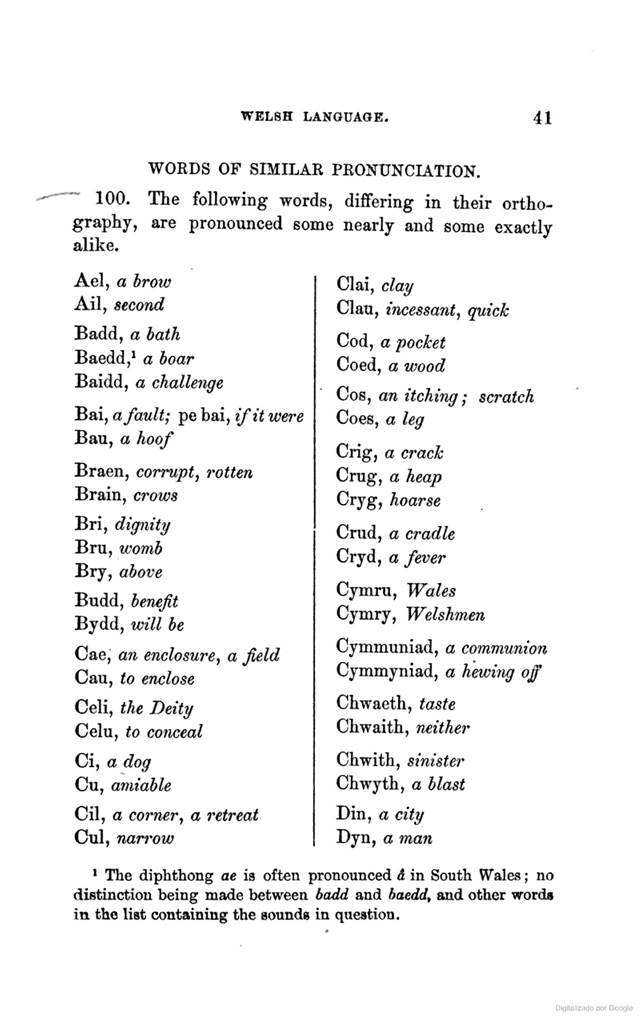

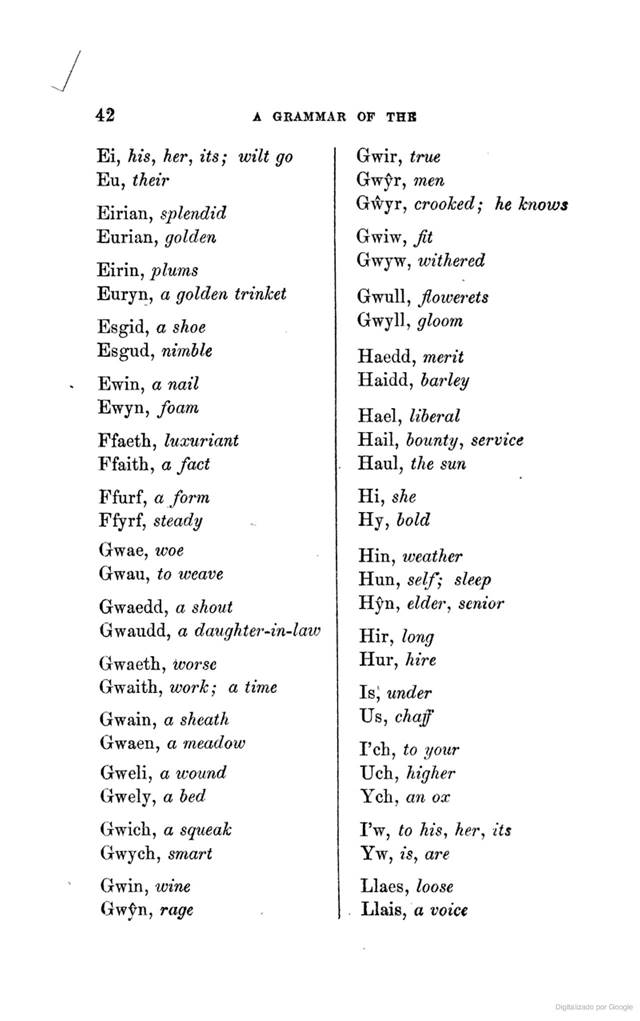

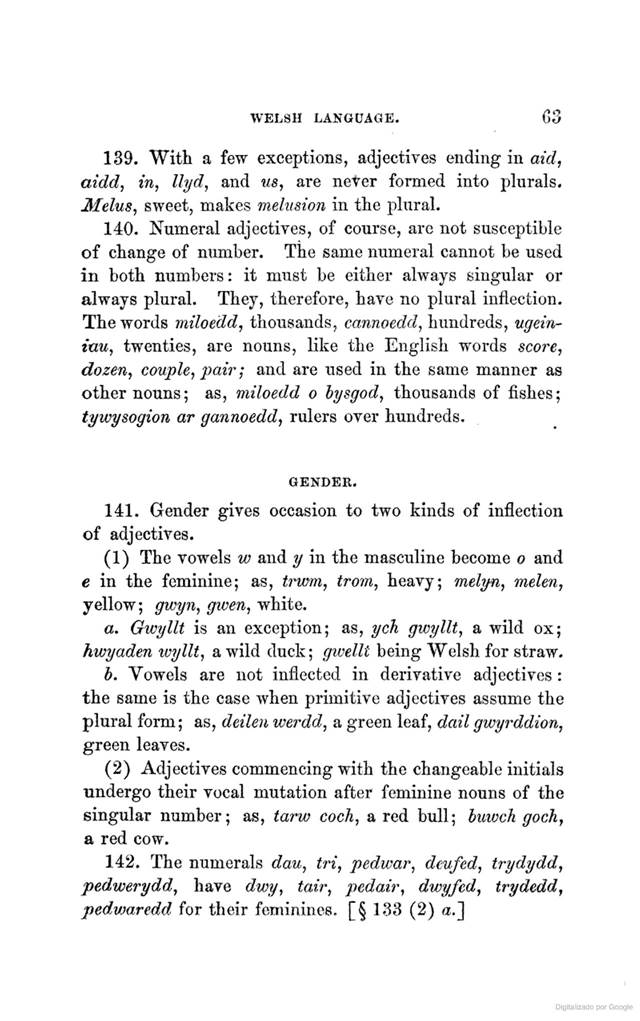

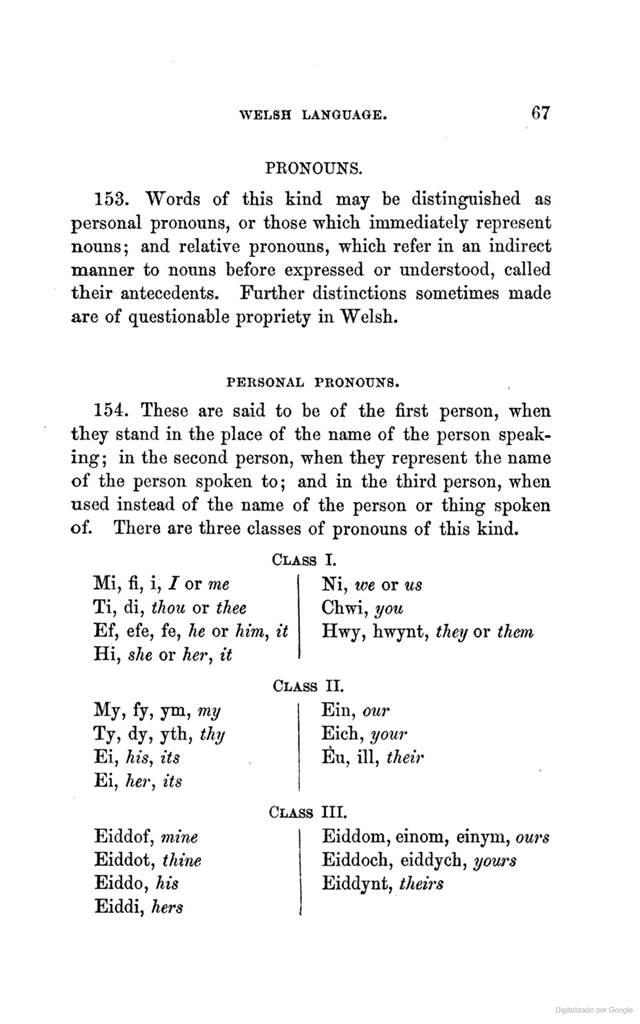

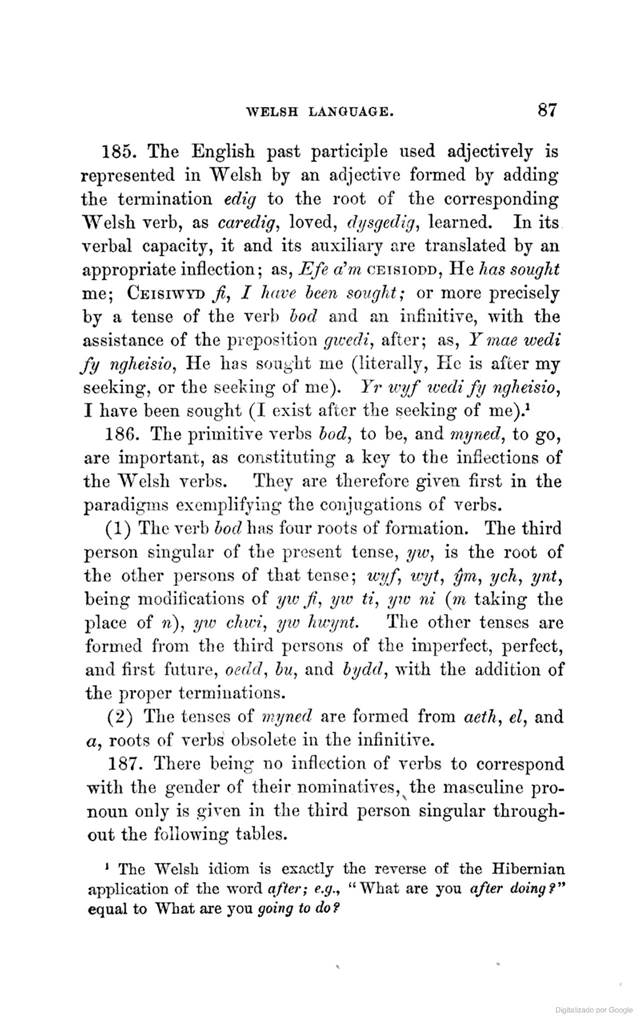

small cabin, a hut.