|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6355) (tudalen 000_1)

|

STUDIES

IN

WELSH PHONOLOGY

SAMUEL J. EVANS, M.A. (Lond.)

1870-1938

Author of The Elements of Welsh Grammar:

The Latin Element in Welsh;

Welsh

and English Exercises:

Welsh Parsing and Analysis:

Questions

and Notes on Welsh Grammar

Editor of "Drych y Prif Oesoedd " with Introduction and Notes

(Guild of Graduates' Series.)

Joint Editor Qf Chaucer's Prologue and Knight's Tale.

LONDON: DAVID NUTT, LONG ACRE, W.C.

NEWPORT, MON.: JOHN E. SOUTHALL, Dock STREET.

1909.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6356) (tudalen 000_2)

|

PREFACE.

THE right of Welsh to an honourable place in our system of education has been

amply recognised of late years in the schools and colleges of the

Principality. The movement for the introduction of this subject into the

curriculum is not an isolated fact, or the feverish dream of a few

irresponsible enthusiasts.

It

is a part of the Educational renascence which has stirred and possessed the

nation for the last forty years. It has a counterpart in the recent upheaval

in Western Europe and in America for the due recognition of the mother tongue

in education, both as a mental discipline and a material gain, and in the

main its methods must be those sanctioned for modern languages by the leading

educationists of all countries.

It is

universally recognised that a training in phonetics must constitute an

essential and organic part of the "Reform movement." But while

English, French, and German sounds have been carefully analysed, classified,

and compared, little has been done for this department of Welsh study outside

the lecture rooms of our National Colleges. Sir John Rhys's Lectures on Welsh

Philology - the only work yet issued that gives much attention to the subject

- is out of print, and its Phonology is mainly historical,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6357) (tudalen 000_3)

|

The

author is well aware that these Studies can lay no claim to any finality, but

he believes that as they embody careful observation extended over a number of

years, and a systematic attempt at equating and differentiating the sounds of

Welsh, English, and French — the three languages with which Welshmen are most

intimately concerned —they will not fail to advance the cause of Welsh

education, and enable the teacher to adopt more completely for Welsh and

English, the method already adopted in most secondary schools for French and

German. He has allowed himself the pleasure of a frequent digression into the

field of Etymology, wherever, by so doing, he could throw light on any point

of Phonetics.

The

author has derived useful hints from the writings of Sir John Rhys, Dr.

Silvan Evans, Professors Anwyl and Morris Jones, Zeuss and Loth, Brugmann,

Giles and Peile, and is in a special degree indebted for many suggestions to

the works on Phonetics by Viëtor and Passy, Sweet and Rippmann. He will be

grateful for any suggestions that may contribute to greater lucidity or

accuracy.

LLANGEFNI, December, 1908.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6358) (tudalen 000_4)

|

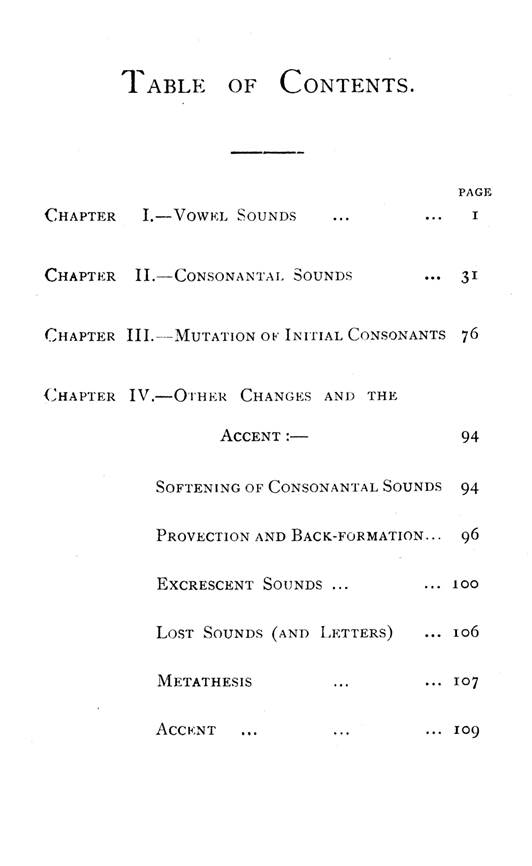

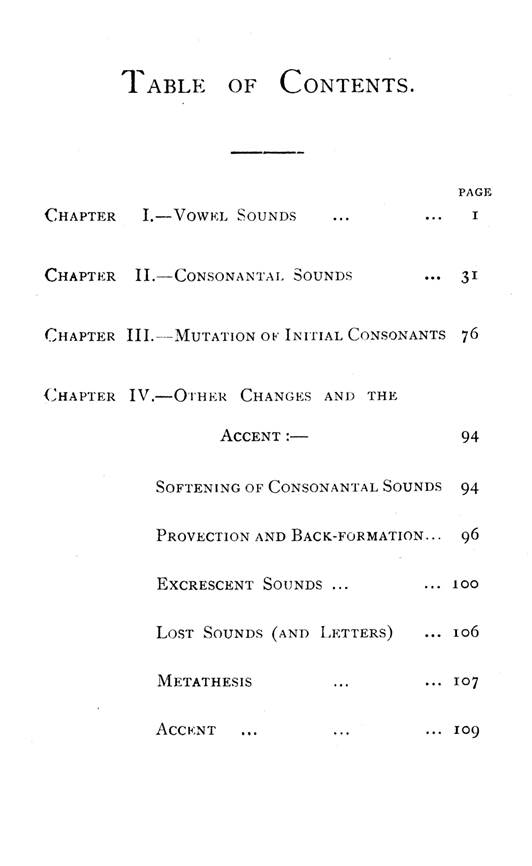

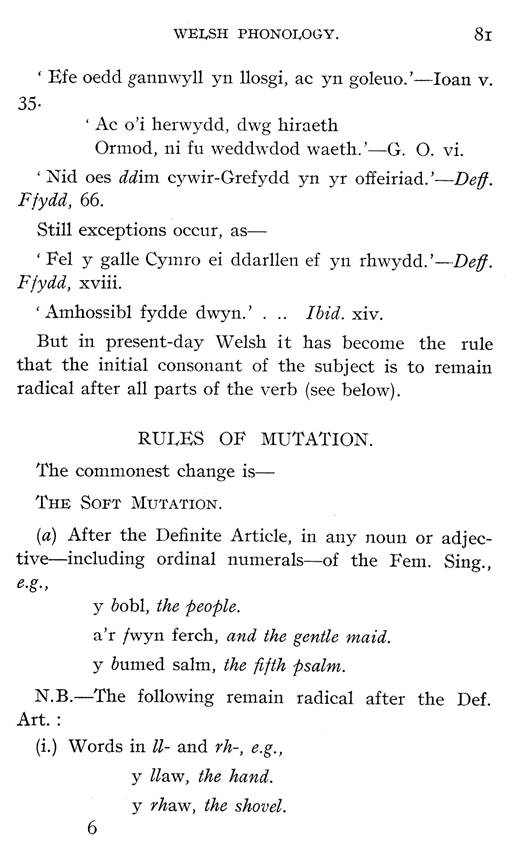

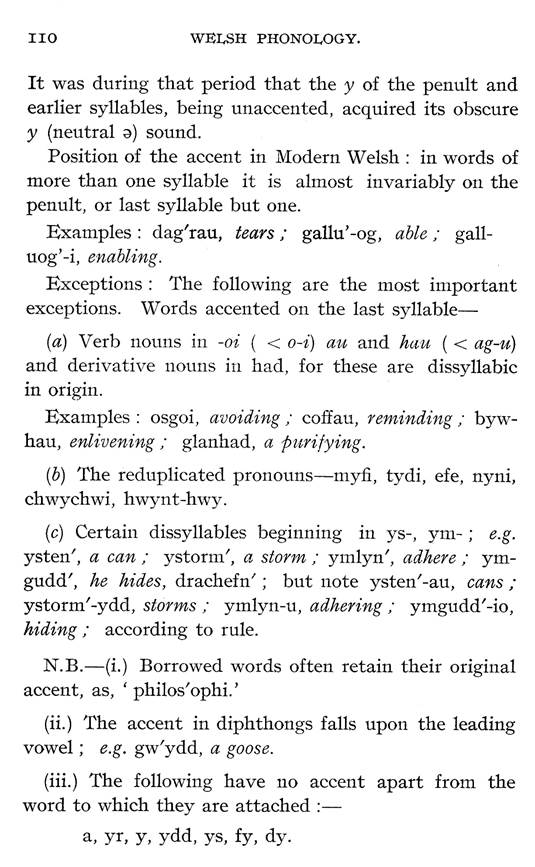

TABLE OF CONTENTS. CHAPTER CHAPTER

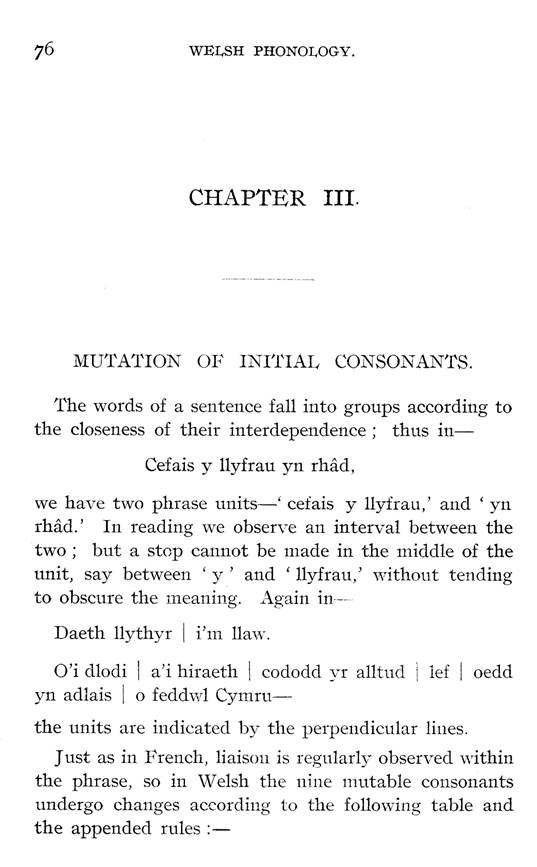

I.—VOWEL SOUNDS II. CONSONANTAL SOUNDS MUTATION OF INITIAL CONSONANTS CHAPTER

Ill. CHAPTER IV.—OrHER CHANGES AND THE ACCENT SOFTENING OF CONSONANTAL SOUNDS

PROVECTION AND BACK-FORMATION. • . EXCRESCENT SOUNDS ... LOST SOUNDS (AND

LETTERS) METATHESIS ACCENT PAGE 1 31 76 94 94 96 100 106 107 109

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6359) (tudalen 000_5)

|

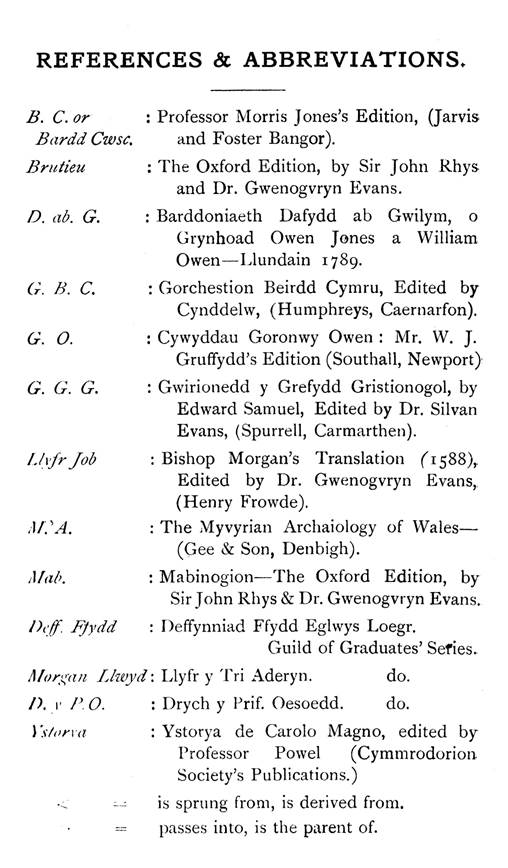

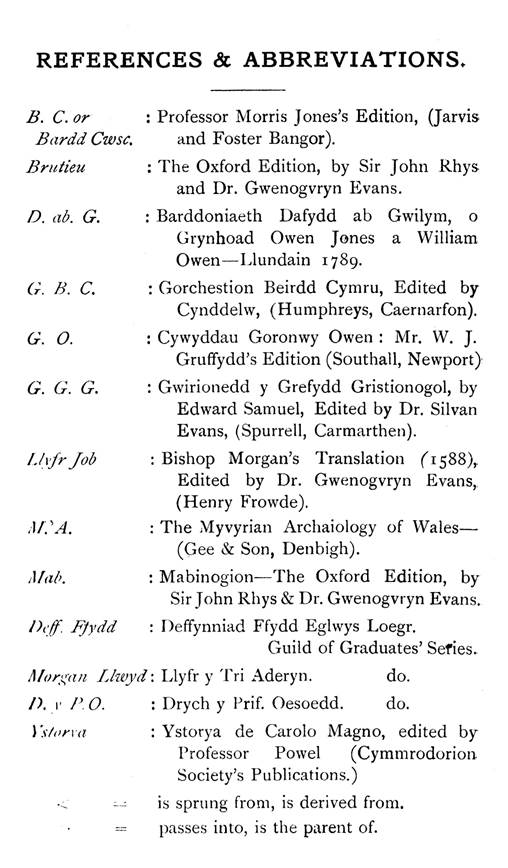

REFERENCES

& ABBREVIATIONS.

B.C. or Bardd Cwsc.: Professor Morris Jones's Edition, (Jarvis and Foster

Bangor).

Brutieu: The Oxford Edition, by Sir John Rhys and Dr. Gwenogvryn Evans.

D. ab G.: Barddoniaeth Dafydd ab Gwilym, o Grynhoad Owen Jones a William Owen

- Llundain 1789.

Dem FJydd:: .:: Gorchestion Beirdd

Cymru, Edited by Cynddelw, (Humphreys, Caernarfon). Cywyddau Goronwy Owen:

Mr. W. J. Gruffydd's Edition (Southall, Newport): Gwirionedd y Grefydd

Gristionogol, by Edward Samuel, Edited by Dr. Silvan Evans, (Spurrell,

Carmarthen). • Bishop Morgan's Translation (1588),. Edited by Dr. Gwenogvryn

Evans, (Henry Frowde).: The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales— (Gee & Son,

Denbigh). Mabinogion--—rrhe Oxford Edition, by Sir John Rhys & Dr.

Gwenogvryn Evans. • Deffynniad Ffydd Eglwys Loegr. Guild of Graduates'

Series. /!/orqqan

Llwyd: Llyfr y Tri Aderyn. Drych y Prif. Oesoedd. do. do. )

's/orra: Ystorya de Carolo Magno, edited by Professor Powel (Cymmrodori01m

Society's Publications.) is sprung from, is derived from, passes into, is the

parent of.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6360) (tudalen 001)

|

WELSH

PHONOLOGY.

CHAPTER 1.

VOWELS.

No

study of the sounds of a language can be considered satisfactory which does

not investigate to some extent their physiological basis.

The

nature and the timbre or quality of every sound may be determined by

reference to the vocal organs concerned in its production. Thus p, t, c (as

in Welsh gardd, Eng. get) are called Mutes or Checks, because the passage of

the breath is momentarily stopped before the sounds are uttered. If the vocal

chords are not brought into action at all, the sounds are p, t, c, while for

b, d, and g some vibration is necessary.

The

Vowels on the other hand are primarily the result of the vibration of these

chords, but their distinctive timbre is determined by a number of secondary

tones produced by a peculiar configuration of the mouth. The shape of the

cavity is largely dependent upon the position of the stopper or tongue and

the lips. For one

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6361) (tudalen 002)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

position of the stopper the mouth may be closed or at any intermediate stage

up to wide open. Again, the lips may be drawn back, yielding ' unrounded '

vowel sounds, while " rounded " vowels are those produced when the

lips are brought over the mouth so as to diminish the orifice. French u as in

vu, lune, and Welsh w in cwm, swn, are extreme instances of rounded vowels.

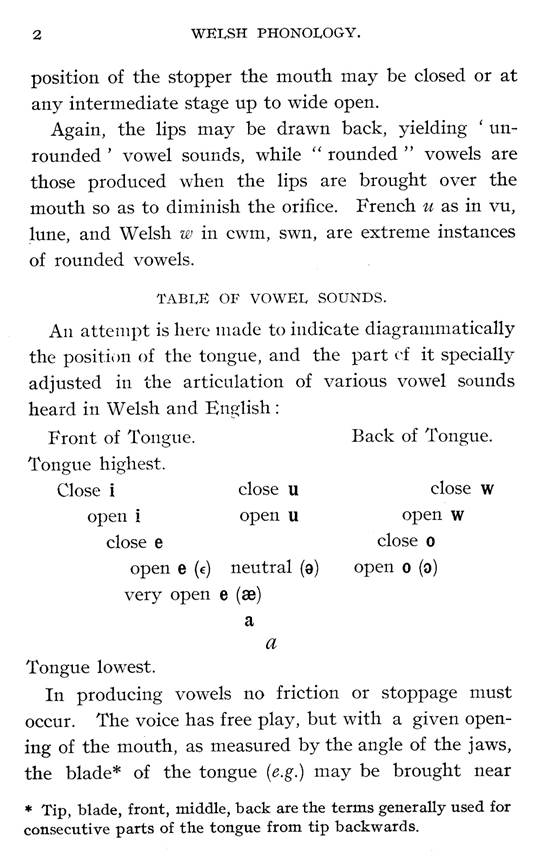

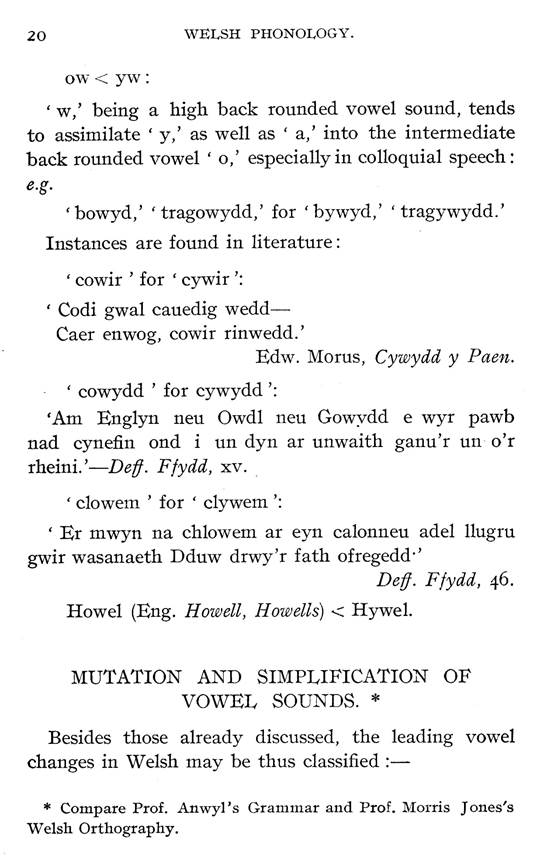

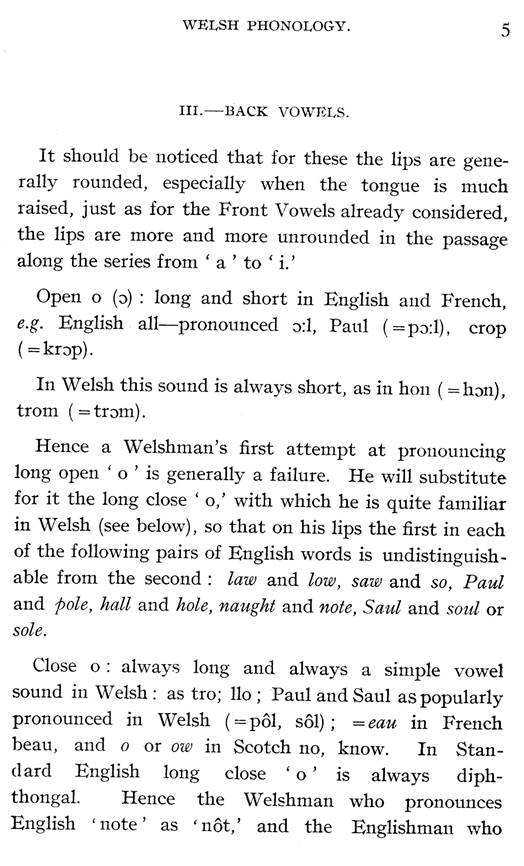

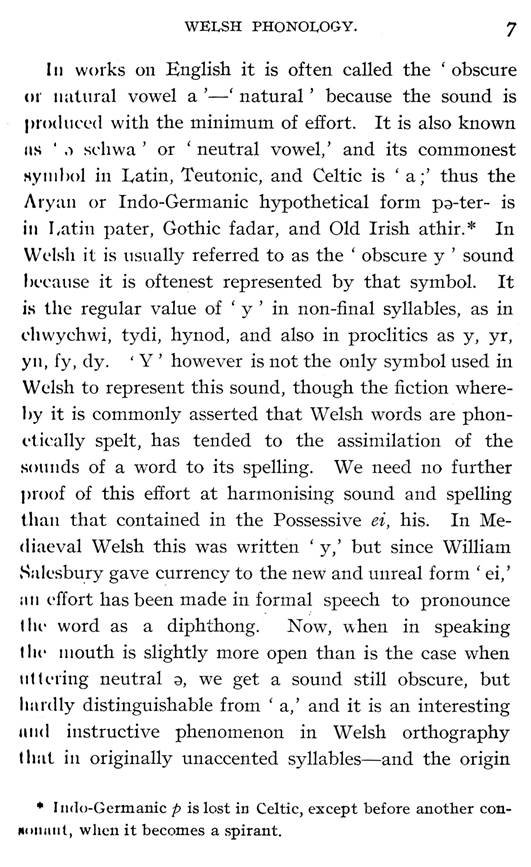

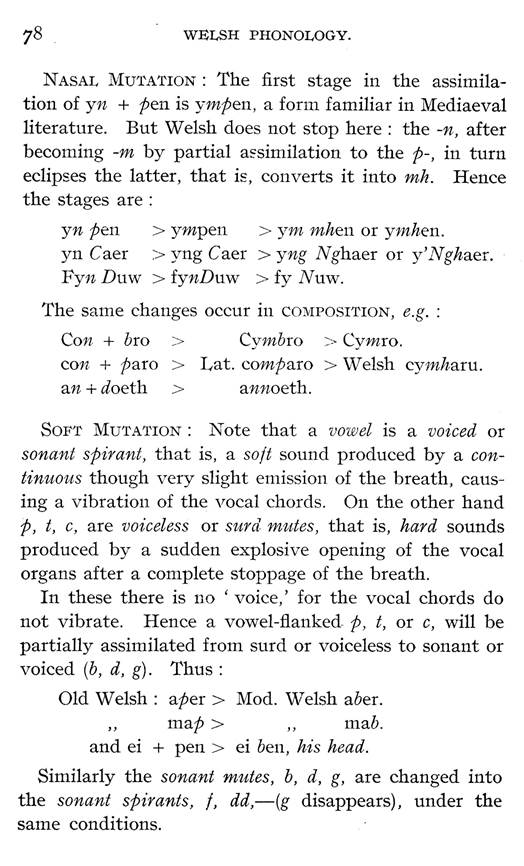

TABLE OF VOWEL SOUNDS.

All attelul)t is here Ill'ade to

indicate diagranlmatically the position of the tongue, and the part ef it

specially adjusted in the articulation of various vowel sounds heard in Welsh

and English:

Front of Tongue. Tongue highest.

Close i open i close e close u open u Back of Tongue. close w open w close o open o (o) open e (G) neutral (e) very open e (æ) a a Tongue lowest.

In producing vowels no friction or

stoppage must occur. The voice has free play, but with a given opening of the

mouth, as measured by the angle of the jaws, the blade* of the tongue (e.g.)

may be brought near *

Tip, blade, front, middle, back are

the terms generally used for consecutive parts of the tongue from tip

backwards.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6362) (tudalen 003)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

3 tille front palate, yielding the '

close i ' of the table: or if the mouth be somewhat more open and the

interval between the tongue and palate be in the slightest degree increased

the timbre is that of ' open i.' This shade of difference in the aperture,

together with an accompanying small change of the part raised of the tongue,

constitutes the distinction indicated in the table by the epithets ' close '

and ' open. '

The symbols in brackets are from the

Alphabet of the Association Phonetique Internationale, and will be used for

phonetic transcription in this book. We will now discuss the vowel sounds in

greater detail.

I.—MEDIO-PALATAL: clear a, neutral

a.

a: This sound is produced by very

slightly raising the fronto-medial part of the tongue. It is heard in

Welsh—calon, tad. French—ma, rage. It is unknown in Standard English, but in

the North the ' a ' in such words as ' pat ' and ' man ' has this value. 011

the other hand, English has two 'a'-sounds unknown in Welsh outside certain

dialects, viz. (i.) a, as in father. It is produced by slightly lifting the

middle of the tongue, that is, the part immediately behind that raised in

articulating the ' a ' in Welsh tad. It IS the sound of ' a ' in French åme,

pas. 'IAhis is the timbre often given to ' a ' in Cloriannydd, and the first

' a ' in Bala by English speakers.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6363) (tudalen 004)

|

4 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

The failure of many Welshmen to

produce without much practice this English a sound is one of the chief

elements in the so-called Welsh accent imported by them into English speech.

(ii.) æ: This perhaps is the commonest ' a '- sound in English. Heard in

glad, man, sad, &c. It is not as open as the Welsh ' a,' the angle of the

jaws being somewhat smaller and the tongue higher. An Englishman speaking

Welsh provokes a smile on the part of a native more on account of the

peculiar æ timbre he gives to the Welsh ' a ' than because of his blunders

over ' 11 and ' Ch.' IL—FRONT VOWELS. Open e (e): as in eto, erddi, echnos.

This sound occurs also in English, as ' let,' ' met.' ai ' in French paix,

and the Close e: as in rhed • first part of the diphthong in English pale,

make. Welsh close long e is a simple sound, while in English it is invariably

diphthongal, thus ' make ' and ' pale ' are pronounced meik, peil. Failure to

notice this difference accounts for the occasional articulation of these

words as mék, pél, on Welsh lips. Teachers in Elementary and County Schools

in the Principality will readily appreciate this point. Open i: as in erlid •

Close i: as in hir: in si. English, pill. English, ee in peel: French, i

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6364) (tudalen 005)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

Ill.—BACK VOWELS. 5 It should be

noticed that for these the lips are generally rounded, especially when the

tongue is much raised, just as for the Front Vowels already considered, the

lips are more and more unrounded in the passage along the series from ' a '

to ' i.' Open o (o): long and short in English and French, e.g. English

all—pronounced o:l, Paul ( crop ( = krop). In Welsh this sound is always

short, as in hon ( hon) , trom ( = trom). Hence a Welshman's first attempt at

pronouncing long open ' o ' is generally a failure. He will substitute for it

the long close ' o,' with which he is quite familiar in Welsh (see below), so

that on his lips the first in each of the following pairs of English words is

undistinguishable from the second: law and low, saw and so, Paul and pole,

hall and hole, naught and note, Saul and soul or sole. Close o: always long

and always a simple vowel sound in Welsh: as tro; 110: Paul and Saul as

popularly pronounced in Welsh ( =p61, s61): =eau in French beau, and o or ow

in Scotch no, know. In Stand ard English long close ' o ' is always

diphthongal. Hence the Welshman who pronounces English ' note ' as ' not,'

and the Englishman who

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6365) (tudalen 006)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

pronounces Welsh tro as trow, are

equally wide of the mark. Open w: always short, as trwm: so in English, full.

oo in English pool, Close w: examples llw, mwg and ou in French sou. lv.

MIXED VOWELS. 'A' and ' a ' have already been referred to (see i. above). As

the neutral will have to be discussed in greater detail, we shall begin this

series with Close u: as u in Welsh un, pur, and y in h9n. Open u: as ' y ' in

hyn, byr, and ' u ' in alltud. These two sounds differ from French ' u ' in

that the latter is (1) a blade and not a front or medial sound, and (2) more

rounded. Neutral: This sound is usually represented by phoneticians as an

inverted ' e ' thus a. It is produced by closing the mouth rather more than

is done in articulating the a of English father, and slightly elevating the

middle of the tongue. It is variously represented in English By ' a ' in

(e.g.) India, America, attend, villa, ar er or o beggar, altar. father, weaker. sudden. purple. sailor. son, harmony.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6366) (tudalen 007)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

7 In works on English it is often

called the ' obscure natural vowel a natural ' because the sound is or

produced with the minimum of effort. It is also known o schwa ' or ' neutral

vowel,' and its commonest ill Latin, Teutonic, and Celtic is ' a;' thus the

Aryan or Indo-Germanic hypothetical form po-ter- is in Latin pater, Gothic

fadar, and Old Irish athir.* In Welsh it is usually referred to as the '

obscure y ' sound because it is oftenest represented by that symbol. It is

the regular value of ' y ' in non-final syllables, as in chwychwi, tydi,

hynod, and also in proclitics as y, yr, yn, fy, dy. ' V' however is not the

only symbol used in Welsh to represent this sound, though the fiction whereby

it is commonly asserted that Welsh words are phonetically spelt, has tended

to the assimilation of the sounds of a word to its spelling. We need no

further proof of this effort at harmonising sound and spelling than that contained

in the Possessive ei, his. In Me(liaeval Welsh this was written ' y,' but

since William Salesbury gave currency to the new and ullreal form ' ei,' all

effort llas been made in formal speech to pronounce t he word as a diphthong.

Now, vvhen in speaking t he 111011th is slightly more open than is the case

when uttering neutral a, we get a sound still obscure, but hardly

distinguishable from ' a,' and it is an interesting instructive phenomenon in

Welsh orthography t lint in originally unaccented syllables—and the origin *

Indo-Germanic p is lost in Celtic, except before another connonalit, when it

becomes a spirant.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6367) (tudalen 008)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

of this sound is to be looked for in

the absence of accent a ' and ' y ' are very freely interchanged. We shall

give a fairly long list, as the question will come up again in various forms.

INTERCHANGE OF A AND V. Mediaeval yn and an English our. Mediaeval ych and

awch* = English your. The Relative Pronoun y for a is sometimes met with in

Mediaeval and early Modern Welsh V wneuthur yn gyuurd gwr ac y bei arglwyd ar

y sawl vrenhined hynny. '—Mab., 82. Nid ei gair nhwy y saif. '—Llyfr y Tri

Aderyn, 192. Y digred y welaist gynneu.' Bardd Cwsc, 32. P wy a haeddei

uffern well na chwi, y fyddei'n hel ac Yll dyfeisio chwedleu. '—Ibid. 95. O flaen pob Llith, y Gweinidog y

ddywed.' Rubric the Te Deum in the Prayer Book. For the same

reason a is occasionally used where we should now use y: Y mae ynys parth

hwnt y ffreine yn gadwedic or mor o bop tu idi, ac a uu gewri gynt yn y chyuanhedu.' Bruts 52. Od oes ddim ynom a ellir craffu arno.—-Defryniad Ffydd, 65 (cf

pp. 92, 150). * For the ' w ' in awch see below.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6368) (tudalen 009)

|

Ymha herwydd (y dolwg) ? Defyniad Ffvdd,

191. amgeledd and ymgeledd Do, ebr ynte, rai unic a dihelp a Phell oddiwrth

ymgeledd. '—Bardd Cwsc, 57. amddifad and ymddifad. anlddiffyn and ymddiffyn.

ychwaneg and achwanec (Mediaeval) NIab. 209. ath iarllaeth titheu heuyt yn

achwanec. y vreham for Abraham. Ystorya de Carolo, 20. anial and ynial: '

Vnteu peredur a gyehwynnwys racdaw. Sef y deuth y goet mawr ynyal. '—Mab.

200. Angharad and Vgharat (Mediaeval): Nachaf ygharat law eurawc yn kyuaruot

ac ef.' Mao. 215. {Illi(lano and ymdano . 'A pheredur a gyuodes, ac a wisgawd

y arueu ym(lanaw ac

ymdan y uarch.'—Mab. 217. y for y and afory: a thost yw gennyf

welet ar was kyn uonhedicket a thi y (lihenyd a vyd arnat avory.' Mab. 216.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6369) (tudalen 010)

|

10 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

canhebrwng and cynhebrwng: dyma

Ganhebrwng yn mynd heibio. '—Bardd Cwsc, 28. cyn and the somewhat unliterary

can, with the Equal Degree: A phe bai un gan ffoled a gwneuthur hynny. '—G.

0., Llythyrau. canfas and cynfas. dynwared and danwared: danwaret y

kyweirdabei a welsei . Vlab. 195. Mediaeval ys and as,—Extended forms of the

Infixed Pronoun of the 3rd person: Pei as gattei lit idaw. '—M ab. 274. Pei

as gwypwn mi ae dywedwn.' Mab. 130. Pei ys gwypwn ny down yma. '—M ab. 29.

ambell and ymbell: Rhaid yw cyd-ddwyn ag ymbell fai. '—Deffyniad Ffydd, p.

xiii. Ilysenw, and the colloquial North Wales llasenw. This word is sometimes

' blasenw ' in Anglesey. afagddu and y fagddu: 'A chroesaw fyd tiffernol ! a

thydi Afagddu, ddyfnaf lyngclyn, derbyn fi.' I. D. Ffraid: coli Gwyn/a, i.

303-4. Cydfydd y Fall a'i gallawr, Cår lechu'n y fagddu fawre '—G. O.: Y Farn Fawr. It will be noticed that the variation is commonest in the initial

syllable, but it occurs in other positions, as—

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6370) (tudalen 011)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

boly and bola, from the Brythonic

bolg. Beth yssyd yn y boly hwnn heb ef. '—M ab. 38, hely and hela, from the

Celtic root selg. 11 eiry and eira, from the root seen in Latin argentum: [V]

petheu draw sy'n perthyn i drafaelwyr mynyddoed(l eiryog. '—Bardd Cwsc, 57.

Silliilarly, while gwely is the usual form of the word for bcd, the plural

gwelåu is from the variant singular gwela* ( > gwela-au > gwelåu):

Gwelem rai ar welåu sidanblu. '-—Bardd Cwsc, 23. It Illust not be supposed

that, when these doublets arose, the -y and -a of hely and hela, &c., had

their values in these words. They are rather the two sytnbols which most

nearly represented the neutral 9 Nound which resulted from the vocalisation

of the -g. 'Phe same attempt at representing the obscure vowel Nound is seen

in /»v• a common variant of ' pa ' in Mediaeval litera'A gofyn a oruc idi py

dir oed hwnnw a phy lee' Mab. 184. vowels in unaccented syllables are not

clearly in any language, and this reacts on the for if ' a,' e,' and ' y '

acquire an approxitillitely coinmon value in that position, it follows that

the sound in any given word may be variously reprenetlted by different writers

or even by the same writer (lilTerent tillies sometimes by ' a' and at other

tittles by 'y ' or ' e.' Of course, in a language like re note in Prof.

Morris Jones 's of Bardd Cwsc.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6371) (tudalen 012)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

Welsh, where popular etymology has

played such a prominent part, orthography will shew abundant evidence of it.

Further, adjoining sounds frequently determine the character of the vowel:

thus, ' n,' being an unrounded dental, tends to clarify or palatalize an

obscure or guttural sound, with the result that the sequence ' an ' or ' yn '

sometimes appears as ' en.' Compare English ' Harry ' and ' Hal ' with '

Henry.' In an unaccented syllable the reverse process is not uncommon (see

below). A AND E. Med. -ei > Mod. -ai, as, dysgei > dysgai. Med. -eu

> Mod. -au, as plural SUffX. agor and egor The latter is the regular form

in Lly/r y Tri Aderyn. angraifft and engraifft Kymer agreift o lawer o

betheu. Ystorya de Carolo, 22. anrhydedd and enrhydedd: Mi ath vyrywys yr

enryded a gwassanaeth idaw ef. ' Mab. 200. -deb: the familiar substantival

suffix is -dab in 'Ai cudab yv•l rhoi codwm ? '—G. O.: Cywydd y Calan. Duwdab, dyndab a swydd lestl Grist. '—Contents of 1st Ch. of Gospel acc.

to St. John. fal ( < hafal), now fel. wynebwarth and wynabwarth: 'Ac yn

wynabwerth idi hitheu dy vwrw o honaf i.' Mab. 210.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6372) (tudalen 013)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

The intensive prefix ' en- ' assumes

the form in a few words on the analogy of the negative ' ananaele en + aele: anghysbell <

en + cysbell • 13 anannog < en + root seen in hogi, awch,

eg-ni,* diog,: English ' to egg: ' Latin acer, &c. annwn < en + dwfn,

hence the extremely deep or bottomless pit: anrheg < en + rheg, a gift ,

ansawdd < en + sawdd. Y AND E. brodyr and older broder.t 'Afiachus fu

faich oes fer, Echdoe fryd eich dau froder.' Tudur Aled: G.B.C. 228. deall

and dyall. 'Ac yna y dyallawd Peredur. '—M ab. 216. dyred (now tyred) and

Demetian dere • egni and yni ennill and ynnill: Ny allwn i vyth ennill vy

arglwyd i o dyn arall.' Mab. 176. Ni fynnem bei allem dy ynnill di. '—Ll. y

T. Ad. 188, ysgar and esgar , ysgymun and esgymun. * Dr. Silvan Evans

incorrectly analyses ' egni ' into e + gni. Compare the Author's ' Latin

Element in Welsh,' p. 8.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6373) (tudalen 014)

|

14 WELSH PHONOLOGY, Mercher—older

Merchur—is sometimes Merchyr: Dyw merchyr mae'n bybyr bwyll, Poed yn ddyw

sadwrn didwy11.'—-D. ab G. cxxix. Dydd Merchur y Lludw. '—Prayer Book. Er,'

for, because of, notwithstanding, is regularly ' yr in Mediaeval literature:

Vr y lawn werth. '—Mabe 179, and similarly yrof ( = erof) and yrdaw erddo) as

in Mab. 105. On the other hand the Definite Article ' y ' was sometimes

written ' e,' as E brenhin yna a disgynnawd. '—St. Great, S 85. The Mediaeval

Possessive Adjective ' y ' (his, her, its their) was regularly written ' e '

when (1) Suffixed to a or o . N yt eynt hwy oe bod.' Mab. 32. V wreic ae gwr

ae phlant.' Mabe 32. (2) Used with hun, self: 'A Chyn penn y pedwyryd mis wynt ehun yn peri eu hatgassau.'—Mab. 32. In the same way the Postvocalic or Infixed Personal

Pronoun was ' e ' after ' a,' as Mi ae dywedaf itt, '—Mab. 200. Mi ae Iledeis. '—--NIab. 200, The diminutive suffixes -yn (m.) , -en (f.) , and -an

(common) In Gwynedd the suffix -en is generally pronounced -an, as merlan for

merlen and hogan for hogen,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6374) (tudalen 015)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

15 while doublets like archan and archen

have literary sanction. Further, the interchange of -yn and -an is not

infrequent in literature, as, dynyn and dynan. -an ' has gained currency as a

Hence the form doublet of both ' -yn ' and ' -en.' Examples of the

interchange of ' y,' ' a,' and ' e ' need not be further multiplied. As far

as its origin is accentual—i.e. where analogy or adjoining sounds do not

account for it—it is an illustration of the Law of Ablaut or Vowel Gradation

which is so marked a feature of Strong Verbs in English. The ultimate result

of this weakening due to the absence of accent is the total elimination of

the sound. Thus, while u in cynnull is distinctly articulated, it is

generally elided in cynulleidfa. Maurice Kymn and Elis Wyn leave the ' u '

out in writing. An ' y ' sound follows the ' g ' in tragywydd, but it is

seldom heard and not often written in trag(y)wyddol and trag(y)wyddoldeb •

Dirgelion tragwyddoldeb nis gwn i, A darllain gair o'u gwers nis gelli die'

Caniadau Pro/. J. Morris Jones, 166 For the same reason ' io ' is dropped

from ' Cristnogion ' in ' Defyniad Ffydd,' M. Kymn, as Ni a wyddom fod yn

amser yr Apostolion ddynion Cristnogion. '—65. Plas (compare English Palace):

baswn and basai for buaswn, buasai: rheiny for rhai hynny, and the Venedotian

Cleta and dled for caletaf and dyled, are all instances of the operation of

the Law of Ablaut.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6375) (tudalen 016)

|

16 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

O AND A. The interchange of o and a is

not uncommon in Welsh. In some instances a is merely a weakened o. Examples

'Meredic a ( = o)wyr' (you are) strange men. —Mab. 126. O'r a ( = Lat ex eis

qui), as Dugant bop peth or a oed reit herwyd eu deuawt wrth aberthu gantunt.

'—Brutieu, p. 52. This phrase in Modern Welsh is generally ' a'r a,' and even

' ar a,' as— Yr wyf yn gobeithio fod yr Hanes 011 mor gywir ac mor llawn hefyd ar a ellir ei

ddysgwyl. '—D. y P. O. 7a. Achos from Latin occasio. Achub from

Latin occupo. Sawdwr or sawdiwr from Mid. Eng. soudiour. Beth yw Sawdwr

Iledlwm addycco dy ddillad wrth ei gleddyf, wrth y Cyfreithwyr ? '—Bardd

Cwsc. (Y m) achlud from Lat. occludo. Yrwan is from yr awron ( = yr awr hon)

and not from a diminutive form of awr with the Definite Article ( = yr awran)

as has been sometimes asserted. -am and -om:—am common in Mediaeval

literature and even as late as the 17th century in the 1st plural of the

Aorist and of Pronominal Prepositions, e.g. Ni a doetham y erchi olwen yr gwas hwnn. '—-Mabe 117

(cf. pp. 129, 130, et Passim). Ie heb ynteu bwyll ni awn yr un niver y buam

doe. Mao. 10,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6376) (tudalen 017)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

17 Diolwch y duw kaffel 0-honat y

gedymdeithas honno, ar arglwyddiaeth a gawssam ninheu. '—Mab. 8. With this

regular Mediaeval termination we may compare the -am of the Old Irish

preterite 1st person plu. As m is a rounded consonant, the tendency is to

convert the unrounded and palatal ' a ' into the rounded and more guttural o.

Hence -om is the regular ending in present day Welsh of the 1st plural Aorist,

and 1st plural of Pronominal Prepositions of the ' ataf ' class. As daethom,

buom, cawsom: arnom (Mediaeval arnam). Po and pa with Superlatives Pa uchaf

yr ymgodant isaf y cwympant.—Lly/r y Tri Aderyn, p. 212. 'A' changes into ' o

' especially when adjoining a guttural like ' w ' or a rounded sound like ' f

' or ' m.' In writers of the 16th century and later ' aw ' tends to pass into

' ow ' in words of more than one syllable a change practically unknown in

Mediæval literature. Maurice Kyffm in Deffynniad Ffydd Eglwys Loegr (1595)

shews an especial fondness for ' ow: ' thus he writes— nowfed, anhowsder,

howsach, yr owron, mowrion, cowri, iniownder, odidowgrwydd, &c. Bardd

Cwsc has Ilownion for llawnion. So in Demetian and Gwentian, forms like mawr,

mawredd, are regularly mowr, mowredd. Mediaeval cawad (a shower) is now more

usually cawod or cafod, though the ' a ' is still retained colloquially in

Demetian. But the student must here be warned against the somewhat natural

tendency to regard a 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6377) (tudalen 018)

|

18 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

modern literary form as a lineal

descendant of that found in our Mediaeval literature. The best prose of the

pre-Reformation era was in South Welsh. The Mabinogion, the Bruts, and the

Laws of I-Iywel Dda were all written in that dialect. On the other hand, in

the 16th and 17th centuries and early 18th, a galaxy of able writers and

translators in North Wales eclipsed their contemporaries in the South, and

their productions came to be regarded as the standard of Welsh composition.

It. follows that many Venedotian peculiarities gained literary currency for

the first time, supplanting rather than growing out of the Demetian

peculiarities of older literature. Thus it is more correct to regard cawod

and cawad as coexisting in sister-dialects than as having developed one out

of the other. The same explanation holds good in the case of Demetian ef a

with): both are etymoor ef å) and Venedotian e/o ( logically the same and

mean literally ' he and ' or ' he with.' It is natural that in the form ' efo

' the etymology of the phrase should be obscured, and then ' efo acquired the

general meaning ' with,' and came to be used with other than the 3rd sing. masculine,

e.g. Dos di efo

foe Gweddiwn efo'n cyd-Gristianogion. '—G. Mechain. It may

be noted as further evidence of the origin of efo that before vowels the

fuller form ' efog ' is sometimes used ef åg), annogaeth i bob dyn i ystyried

eu ' Efog ( ffyrdd a'u crefydd. '—Agoriad (1703).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6378) (tudalen 019)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

19 The simple preposition o (for å) is

often used in the dialect of Glamorgan to denote the instrument, as, ' Codi

glo o'r rhaw (å'r rhaw) = throwing up coal with a shovel. * It is interesting

to note that the history of the English language shews a similar break of

continuity. Modern standard English is a direct descendant not of the

vigorous i West Saxon dialect of King Alfred—the dialect in which all extant

Old English literature is written— but of the Midland or Mercian which gained

literary currency and precedence in the 14th century due to a complexity of

causes, but mainly because that consummate literary artist—Chaucer—wrote his

inimitable Canterbury Tales in that dialect. Thus it is that we write ' did '

and not ' dud,' which would be the Modern form of the Old English (i.e. West

Saxon) dyde, and, to take only one other instance, the word all is sprung

from the old Midland all, and could not be explained by reference to the West

Saxon eall. But to return to the interchange of ' a ' and ' o,' a few other

instances may be mentioned Vstondard ' (from Eng. standard). ——1/1 ab. 155.

Bonllef ' ( = banllef) .—Bardd Cwsc, p. 107. Na, nag, and Mediaeval no, nog,

after a comparative. Orgrephid for argrephid.—Llyfr Job (Dr. Morgan), 43.

Coron and coran. Cawgiau and cowgiau, &c. In Anglesey and Carnarvonshire

dafad is regularly pronounced dafod. * Quoted from Mr. John Griffiths's V

Wenhwyseg, ' p. 19. Published by J. E. Southall, Newport.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6379) (tudalen 020)

|

20 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

ow < yw: w,' being a high back

rounded vowel sound, tends to assimilate ' y,' as well as ' a,' into the intermediate

back rounded vowel ' o,' especially in colloquial speech: ' bowyd,' '

tragowydd,' for ' bywyd,' ' tragywydd.' Instances are found in literature:

cowir ' for ' cywir Codi gwal cauedig wedd Caer enwog, cowir rinwedd.' Edw.

Morus, Cywydd y Paen. cowydd ' for cywydd 'Am Englyn neu Owdl neu Gowydd e

wyr pawb nad cynefin ond i un dyn ar unwaith ganu'r un o'r rheini, '—Def.

Ffydd, xv. clowem ' for ' clywem . Er mwyn na chlowem ar eyn calonneu adel

Ilugru gwir wasanaeth Dduw drwy'r fath ofregedd•' Def. Ffydd, 46. Howel (Eng.

Howell, Howells) < Hywel. MUTATION AND SIMPLIFICATION OF VOWEL SOUNDS. *

Besides those already discussed, the leading vowel changes in Welsh may be

thus classified: * Compare Prof. Anwyl 's Grammar and Prof. Morris Jones's

Welsh Orthography.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6380) (tudalen 021)

|

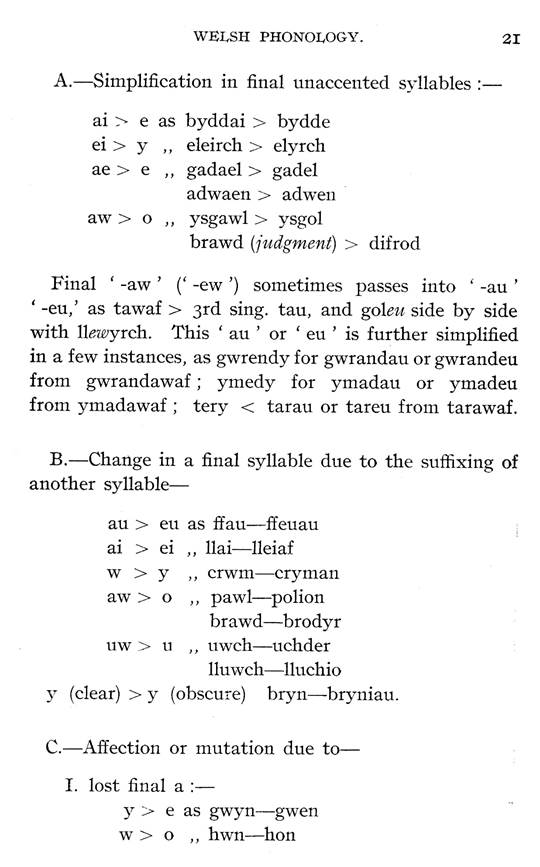

21 A. WELSH PHONOLOGY.

Simplification in final unaccented

syllables e as byddai

bydde y o Final ' -aw eleirch elyrch gadael > gadel adwaen

> adwen ysgawl > ysgol brawd (judgment) > difrod (' -ew ') sometimes

passes into ' -au -eu,' as tawaf > 3rd sing. tau, and goleu side by side

with Ilewyrch. This ' au ' or ' eu ' is further simplified in a few

instances, as gwrendy for gwrandau or gwrandeu from gwrandawaf: ymedy for

ymadau or ymadeu from ymadawaf • tery < tarau or tareu from tarawaf.

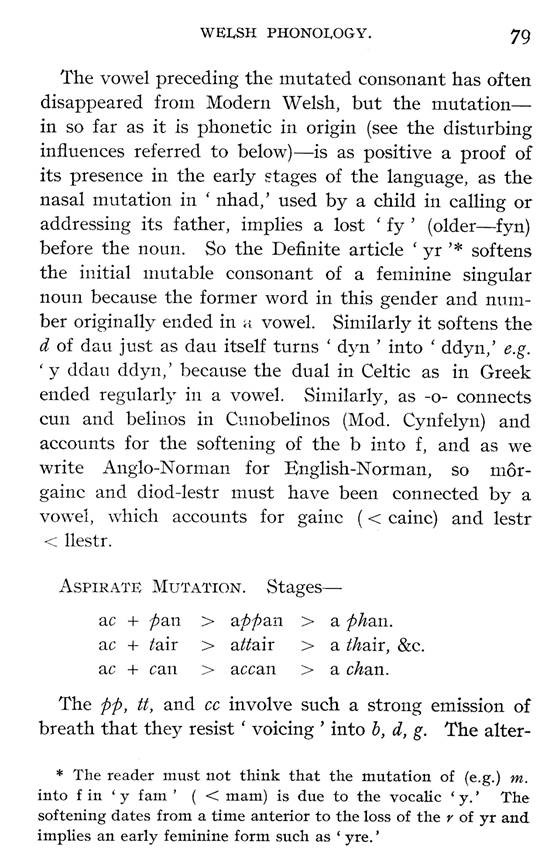

Bo—Change in a final syllable due to the suffixing of another syllable all

> eu as ffau—ffeuau U llai—lleiaf crwm—cryman pawl—polion brawd—brodyr

uwch—uchder Iluwch Iluchio y (clear) > y (obscure) bryn—bryniau.

C.—Affection or mutation due to— I. lost final a: y > e as gwyn—gwen w

> o „ hwn—hon

|

|

|

|

|

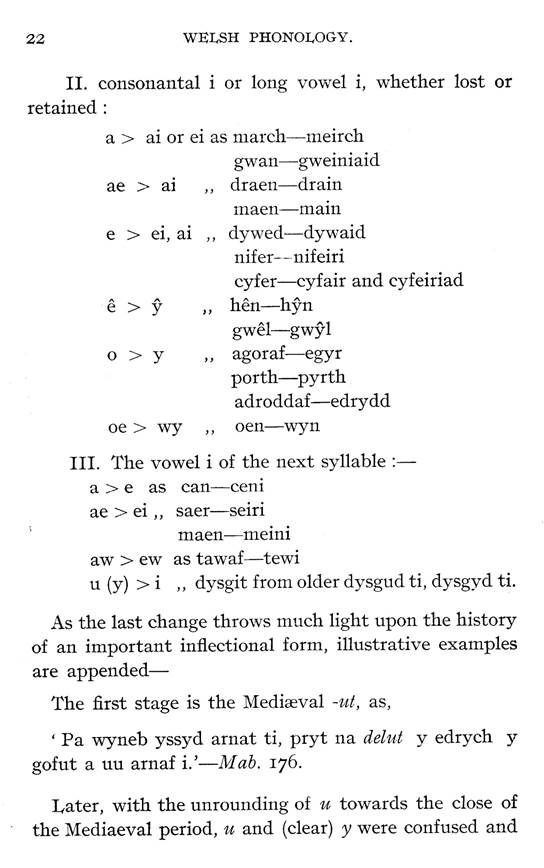

(delwedd F6381) (tudalen 022)

|

22 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

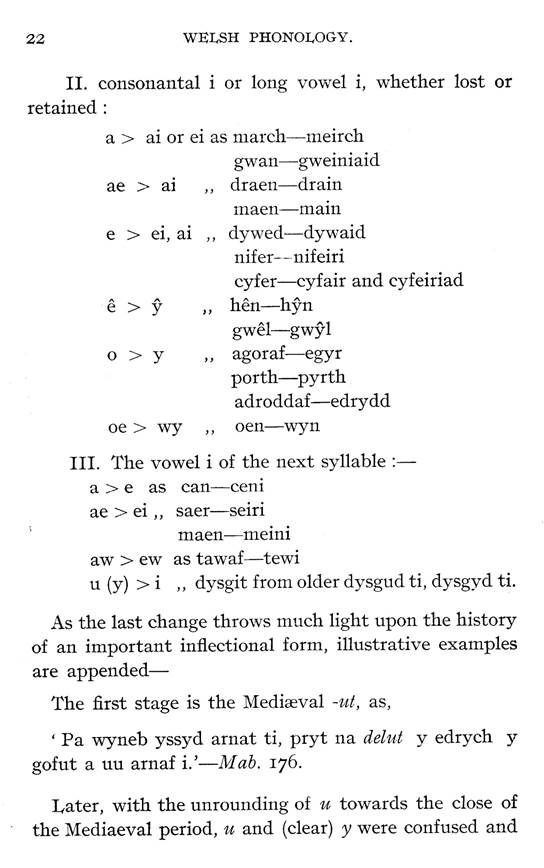

vowel i, whether lost or II.

consonantal i or long retained: meirch a > ai or ei as march gweiniaid

drain —main dywaid ae > ai e > ei, ai oe > wy gwan draen maen dywed

nifer-- nifeiri cyfer—cyfair and cyfeiriad hén—hjn gwél—gwjl agoraf—egyr

porth—pyrth adroddaf—edrydd oen—--wyn Ill. The vowel i of the next syllable:

a > e as can—ceni saer—seiri ae > ei , maen—meini aw > ew as

tawaf—tewi u (y) > i „ dysgit from older dysgud ti, dysgyd tie As the last

change throws much light upon the history of an important inflectional form,

illustrative examples are appended— The first stage is the Mediæval -ut, as,

Pa yssyd arnat ti, pryt na delut y edrych y gofut a uu arnaf i. '—Mab. 176.

Later, with the unrounding of u towards the close of the Mediaeval period, u

and (clear) y were confused and

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6382) (tudalen 023)

|

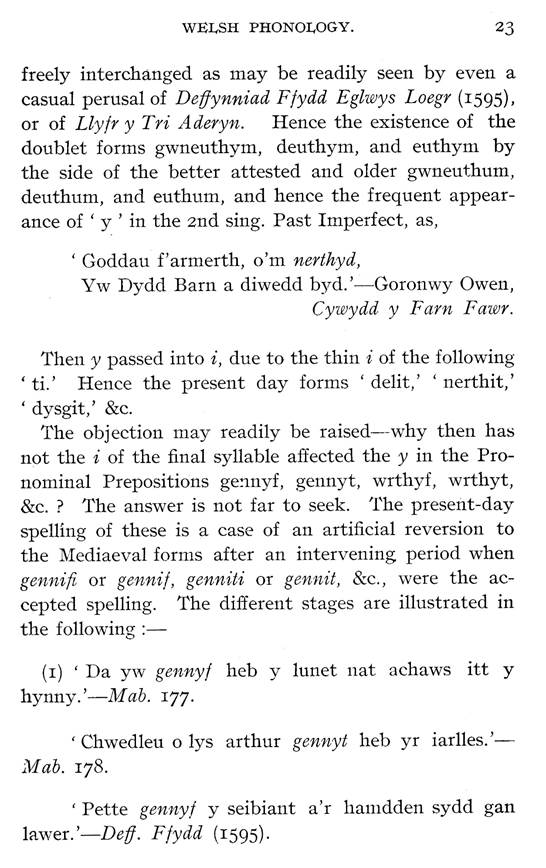

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

23 freely interchanged as may be

readily seen by even a casual perusal of Defynniad Ffydd Eglwys Loegr (1595),

or of Lly/r y Tri Aderyn. Hence the existence of the doublet forms gwneuthym,

deuthym, and euthym by the side of the better attested and older gwneuthum,

deuthum, and euthum, and hence the frequent appearance of ' y ' in the 2nd sing.

Past Imperfect, as, Goddau f'armerth, o'm nerthyd, V w Dydd Barn a diwedd

byd.' Goronwy Owen, Cywydd y Farn Fawr. Then y passed into i, due to the thin

i of the following ti.' Hence the present day forms ' delit,' nerthit,'

dysgit,' &c. The objection may readily be raised—why then has not the i

of the final syllable affected the y in the Pronominal Prepositions gennyf,

gennyt, wrthyf, wrthyt, ? The answer is not far to seek. The present-day

spelling of these is a case of an artificial reversion to the Mediaeval forms

after an intervening period when gennifb or gennif, genniti or gennit,

&c., were the accepted spelling. The different stages are illustrated in

the following . (1) ' Da yw genny/ heb y lunet nat achaws itt y hynny. '—Mab.

177. Chwedleu o lys arthur gennyt heb yr iarlles.' Mab. 178. Pette gennyf y

seibiant a'r hamdden sydd gan lawer.' Def. Ffydd (1595). 26 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

The change of ' uw ' into ' u,' as

uwch——uchder, is rather a case of reversion to a more radical form. The w '

in uwch, awch (Mediaeval, = your), and several other monosyllables, is

intrusive or inorganic: ch is articulated by bringing that part of the

tongue, which is raised for the sound ' w,' a little nearer to the soft

palate so as to cause an audible friction when breath is exhaled. Hence in a

leisurely and careless pronunciation of a vowel—other than ' w '—before ch*,

the tongue in taking up the consonantal position glides through the ' w '

position, and in so doing articulates more or less audibly the ' w ' which is

written in the above words. When another syllable is added, a shorter,

brisker, and consequently more precise articulation of the first syllable is

imperative, with the consequent elimination of the ' w. The ' w ' is of

somewhat later growth in uwch than in buwch, Iluwch, In the Mabinogion the

comparative is regularly spelt uch, as uch penn y pwll.' 216 (cf. 153, 175,

&c.). This is due to the influence of the positive uchel where of course

' w ' does not occur. Still, üwch is met with as in Ac yn dyvot yn ogyfuwch

ar orsed. '—Mab. 8: and in the poetry of Dafydd ab Gwilym (d. 1400) it is

quite comlnot) Nid gwen gwelwdon anghyfuwch, Nid gwyn ewyn Ilyn, na Iluwch.

'—xxix. * ch generally lengthens the preceding vowel in monosyllables.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6383) (tudalen 024)

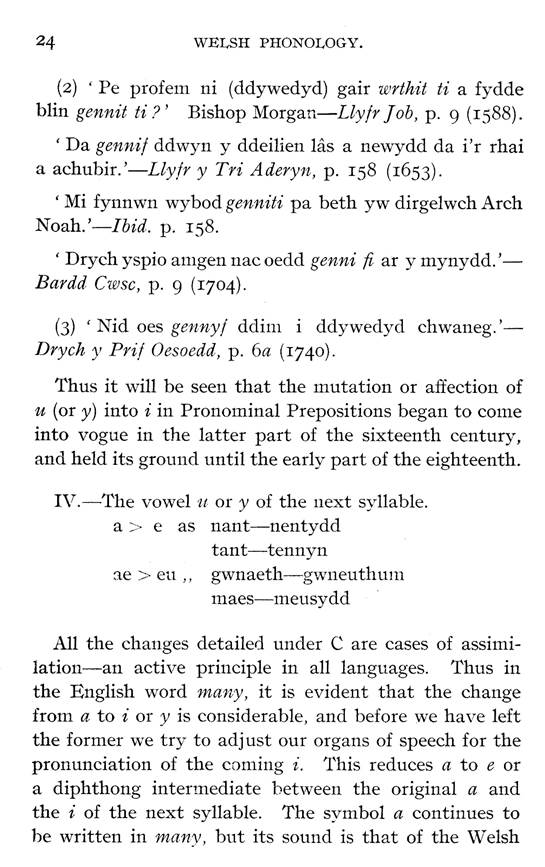

|

24 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

(2) ' Pe profem ni (ddywedyd) gair

wrthit ti a fydde blin gennit ti ? ' Bishop Morgan—Lly/r Job, p. 9 (1588). Da

genni/ ddwyn y ddeilien lås a newydd da i'r rhai a achubir.'—Lly/r y Tri

Aderyn, p. 158 (1653). Mi fynnwn wybod genniti pa beth yw dirgelwch Arch

Noah, '—Ibid. p. 158. Drych yspio anmgen nac oedd genni ar y mynydd. ' Bardd

Cwsc, p. 9 (1704). (3) ' Nid oes genny/' ddilll i ddywedyd chwaneg. Drych y Pri/ Oesoedd, p. 6a (1740).

Thus it will be seen that the mutation or affection of u

(or y) into i in Pronominal Prepositions began to come into vogue in the

latter part of the sixteenth century, and held its ground until the early part

of the eighteenth* I V. The vowel u or y of the next syllable. a e as

nant—nentydd tant—tennyn gwnaeth—gwneuthtllil maes—meusydd All the changes

detailed under C are cases of assimilation—an active principle in all

languages. Thus in the English word many, it is evident that the change from

a to i or y is considerable, and before we have left the former we try to

adjust our organs of speech for the pronunciation of the coming i. This

reduces a to e or a diphthong intermediate between the original a and the i

of the next syllable. The symbol a continues to be written in many, but its

sound is that of the Welsh

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6384) (tudalen 025)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

25 open ' e,' and generally the

spelling is changed to represent the sound, as (1) English men fronm man,

through the intermediate stage mani, mannie (2) Welsh ceni from canaf.

Similarly while Brythonic vindos has becolne Welsh gwyn, the feminine vinda,

through the partial assimilation of the i to the a, has become Welsh gwen.

All the changes given in the above classification are not without exception.

Adwaen and gadael are as common as adwen and gadel, if not more so, while the

change into y in gwrendy, &c., is exceptional. Again the mutation of aw

into o, as in pawl—polion, does not take place in mawrion ( < mawr),

llawnion ( < llawn). Byddai is rarely written bydde to-day, Lost final ' a

' changes ' y ' into ' e,' but it leaves the diphthong ' wy ' unaffected.

Thus while the feminine of gwyn is gwen, the diphthong in mwyn and tywyll is

the same in both genders. Tywell, sometimes met with, is due to the

lilistaken notion that the ' w ' is consonantal, e.g. V nos dywell yn distewi,—caddug V n

cuddio Eryri, Yr haul yng ngwely'r heli, A'r Iloer yn ariannu'r

Ili'. '—Gwallter Mechaill. Silllilarly while ' y ' changes ' a ' into ' e '

as in nentydd, ' y ' in the diphthong ' wy ' is eclipsed by ' w,' and loses

its assimilating power: hence anwyl, arwydd, not enwyl, erwydd.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6385) (tudalen 026)

|

26 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

The change of ' uw ' into ' u,' as

uwch——uchder, is rather a case of reversion to a more radical form. The w '

in uwch, awch (Mediaeval, = your), and several other monosyllables, is

intrusive or inorganic: ch is articulated by bringing that part of the

tongue, which is raised for the sound ' w,' a little nearer to the soft

palate so as to cause an audible friction when breath is exhaled. Hence in a

leisurely and careless pronunciation of a vowel—other than ' w '—before ch*,

the tongue in taking up the consonantal position glides through the ' w '

position, and in so doing articulates more or less audibly the ' w ' which is

written in the above words. When another syllable is added, a shorter,

brisker, and consequently more precise articulation of the first syllable is

imperative, with the consequent elimination of the ' w. The ' w ' is of

somewhat later growth in uwch than in buwch, Iluwch, In the Mabinogion the

comparative is regularly spelt uch, as uch penn y pwll.' 216 (cf. 153, 175,

&c.). This is due to the influence of the positive uchel where of course

' w ' does not occur. Still, üwch is met with as in Ac yn dyvot yn ogyfuwch

ar orsed. '—Mab. 8: and in the poetry of Dafydd ab Gwilym (d. 1400) it is

quite comlnot) Nid gwen gwelwdon anghyfuwch, Nid gwyn ewyn Ilyn, na Iluwch.

'—xxix. * ch generally lengthens the preceding vowel in monosyllables.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6386) (tudalen 027)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

AE AND A1. 27 Although in this essay

we are only indirectly concerned with the representation of sounds in

writing, a short digression may be made to refer to the notations ai and ae.

In Mediaeval Welsh our modern diphthong ai was written ei (ey), and the

sequence ai (or ay—for in Mediaeval writings y is often used with the value

of modern i) was then comparatively rare. A diphthong beginning in a followed

by a palatal vowel was regularly written ae: thus our modern a'i (and his)

was ae, and even a + consonantal i had the same form, as in daeoni. The use

of e for the palatal vowel after a, where we now write ai, long continued a

common feature of Welsh orthography. Hence the ai of English words passed

into ae in most Welsh derivatives, as < fray. ffrae maeden < maiden.

paent < paint. < plain. plaen trafaelio < Middle English or Anglo

French travail, whence Modern English travel. Vspaen < Spain. On the other

hand the verb-noun termination of these derivatives is -io, -o, the very

ending we should expect if the diphthong were ' ai ' as in the English

original, as, gwaith disglair * gweithio. disgleirio. * Cyfiaith—-cyfieithu

is an exception.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6387) (tudalen 028)

|

28 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

Words containing ' ae ' in their final

syllable regularly form their verb-nouns in -u, as arfaeth arfaethu. But for

these borrowed words we have ffraeo, paentio, trafaelio: 'A gymnmerech i

Fardd i'ch plith sy' n chwennych trafaelio ? ' Bardd Cwsc, 6. Still,

trafaelio seems dialectal, for in Dafvdd ab Gwilym the form trafaelu also

occurs . Tra fu'n trafaelu trwy fodd, Trwy foliant y trafaeliodd.' Cywydd

iv., and so regularly in Demetian to-day. THE VALUES OF ' V. Something too

should be said on this question: while the power of every other vocalic

symbol has been already sufficiently indicated, ' y is different. Besides the

neutral a sound, which is always short, and inevitably so, it has the clear

sound of ' u ' in (a) Monosyllables: e.g., dyn, Ilym, ty. Exceptions . it has

the primary or neutral a value in proclitics, that is, words that have no

accent of their own, but are for this purpose read with the following word.

The most common proclitics are ' fy • dy: Y," yr (Definite Article,

Relative Pronoun. Adverb, and Conjunction) .

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6388) (tudalen 029)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

29 (b) In the last syllable of words

of more than one syllable, as gelyn, plentyn. (c) In any syllable when

followed by a vowel, e.g. hyawdledd, gwelyau. (d) In the diphthong ' WY,'

e.g. hwyl, mwynhad. (e) Frequently when preceded by consonantal ' w,' e.g.

gwystlon, wynebau. (f) Generally in the prefix cyd-, and in the first

elements of compounds, if monosyllabic, e.g., cydweithio, Rhydychen,

byrfyfyr, Tyhén, brysneges. N.B.—' y ' has sometimes the value of Welsh ' i,'

as in megys, tebyg, heddyw. VOWELS IN DIALECTS. The simplification of

diphthongs has proceeded much further in dialects than is recognised in the

Welsh literature of the present (lay. It is hardly necessary to add that the

dialects differ considerably among themselves in that respect. This chapter

may be appropriately closed with a few examples of dialectal changes and

vowel values. E ' in final unaccented syllables is pronounced like a ' in the

North West portion of Gwynedd—i.e. in Anglesey, Carnarvonshire, and part of Denbighshire—

and often in Gwentian, as bach(g)an for bachgen. -Au ' and ' -eu ' final have

the value of a ' ill North West Gwynedd and in Gwentian, as— petha, gola.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6389) (tudalen 030)

|

30 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

e ' in the rest of Wales, as— pethe,

gole. 'Ae ' and ' ai ' in final unaccented syllables are pronounced as a ' in

North West Gwynedd and in Gwentian, (i.) as--gadal, perffath, (ii.) ' e ' in

the rest of Wales, as gadel, perffeth. 'Ae ' and ' oe ' in monosyllables are

simplified into å ' and ' 6 ' respectively in Demetian and Gwentian, as— man,

c6s, for maen, coes. 'Ai ' in sollle monosyllables—generally those ending is

pronounced ' ae ' in Demetian, as in 1'— gwaer, taer, for gwair, tair, also

Caen for Cain. 'Au ' in monosyllables is generally pronounced in Demetian and

Gwentian, as— doi, hoil, coi, oir, for dau, haul, cau, aur. oi ' U ' and the

clear ' y ' are generally pronounced ' i in all parts of Wales outside North

West Gwynedd, as— cani for canu, mid for mud, hin for hyn, hin for 11911 or

hun.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6390) (tudalen 031)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

31 CHAPTER 11. CONSONANTS, B AND M.

The relation of these two sounds is intimate. The passage is closed at the

lips. If then the lips are separated to allow the breath to escape, and the

vocal chords are at the same time vibrated, b is articulated. But the lips

may be kept together, and the breath passed out through the nostrils, giving

rise to the sound m. Hence the frequent interchange of m and b, as W. blith

and Eng. milk. mieri and Eng. briar. But in Welsh this is not the only

reason. At least two other contributory causes of considerable importance

exist (1) The soft mutation of both m and b is f, and as the softened initial

is a very common feature in Welsh construction, a word may be more familiar

in that state than in its radical form. Hence a not uncommon re-

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6391) (tudalen 032)

|

32 WELSH PHONOLOGY.

version to the wrong original. Thus

maban (diminutive of ' mab ') commonly occurs under the form ' faban,' as '

ei faban,' ' dy faban,' ' dyma faban tlws.' In Modern Welsh faban has been

referred back to a radical baban ' so often that this doublet has gained a

firm footing in the language. In this particular instance no doubt the

English word ' baby ' materially helped the growth of the doublet. But no

such outside influence can account for ' modrwy,' which is from ' bodrwy

(< bawd + a termination meaning band, cf. aerwy) through the intermediate

' fodrwy.' Fronl early times up to the seventeenth century it was quite

customary to wear rings on the thumbs: but as the custom changed and as rings

were worn on other fingers as well, the origin of ' fodrwy ' was obscured.

Hence its being accidentally referred back to a coined ' modrwy,' which has

now supplanted the more correct form. For a similar change of custom we need

only refer to the English thimble, which is no longer worn on the thumb

except occasionally by sailors in repairing the tough fabric of their sails.

It is clear that the etymological meaning of modrwy could not be known to the

translator of Hosea ii. 13.: Mi a ymwelaf å hi am ddyddiau Baalim, yn y rhai

y gwisgodd ei chlustfodrwyatl a'i thlysau.' A still more curious instance is

' bodo,' the familiar name for aunt in North Cardiganshire. In the light of

this interchange of b- and m-, its origin is at once made it is a shortened

form of modryb with the dimiclear: nutive suffix -o, just as -ie is added in

English to make

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6392) (tudalen 033)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

33

auntie. The shortening of words in this way is a fact

of daily occurrence. Hence Ned for Edward, with the

-n of the 1st sing. possessive adjective prefixed, so Nel

from -n Ellen. -O is a familiar SUffx used to denote

smallness or endearment: Gweno, Deio, Bilo ( Wil-

liam), 1010

Iorwerth), and others will occur to the

reader.

(2) The tendency to refer borrowed words in /- to

radical forms in m- or b- has given endless scope for

diversity of treatment, for while one speaker will refer

volet ' (a gauze veil worn by ladies in the middle ages)

to a radical boled, another may with equal justice con-

sider moled as the correct radical form.

This same keenness for provection accounts for m- in

mal < fal (whence fel) < y fal < hafal, cognate with

Lat. similis. This word is often ' bal ' in Gwentian.

In addition to those already mentioned, the following

are some of the most interesting instances of the changes

here described

bargod, as compared with Latin margo, English

margin

bainc and mainc < A.S. benc, whence English

bench

banon and manon

balaen, balain, balen ( < Milan), a steel blade for

the manufacture of which Milan was celebrated

in the Middle Ages '

bodrydaf and modrydaf '

borddwyd and morddwyd •

bore and English morrow, morning ,

3

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6393) (tudalen 034)

|

34

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

bwysel and mwysel < English bushel

byswynog and myswynog ,

baeddu and maeddu •

beiddio and meiddio:

ben and men (a wagon)

benyw and menyw

bilain and milain ( < Eng. villain)

bignen and mignen, and Eng. bog

bigwrn and migwrn

bwyaid and mwyaid

bwytal and bitail, from Mid. Eng. or Anglo French

vitaille (whenee Mod Eng. victuals), food

Dyvot a oruc gwyr iwerdon hyt att Arthur a rodi

bwyttal idaw. '---Mab. 136.

bydwraig is a half adapted and half translated

form of English mid-wife: ' mid ' > ' bid ' (and

then by popular etymology ' byd,' though the

term makes nonsense) + ' gwraig,' translation

of ' wife.' The English word ' bracelet ' was sub-

mitted to the same piecemeal treatment .

breich ' ( braich) is a correct translation of

brace, which is no other than the French ' bras,'

an arm, and -led is the English -let with the regu-

lar softening of final t after a vowel. The popular

leather) in

etymologist saw the word ' Iledr ' (

the StifflX, and Lewys Glyn Cothi has the rather

amusing couplet*

Gwisgaw breichledr, os medraf,

O arian neu aur a wnaf.'

* See Silvan Evans's Dictionary under Breichledr. '

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6394) (tudalen 035)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

35

Dr. Silvan Evans (v. breichled) is disposed to follow

this fanciful etymology.

burgyn and Eng. morkin

melfed < Eng. velvet:

V tal dan y melfed du

A gae wirion dy garu. '—Bedo Rrwynllys.

miswrn < Eng. visor:

P wy nid yw'n canfod Rhufain .

yr hon a

beintiessid gynt å Iliwieu hyfryd, eithr yr owr'on gan

dynny ei miswrn, y mae'n haws yr olwg, ag yn llai'r

bris arni ' Def. Ffydd, 188.

mwydyn < bwydyn < y bwydyn < abwydyn

mach, meichiai, is cognate with Latin vas, a surety.

c.

c is always hard as in English cat.

Initial c + consonantal w does not occur in native

Welsh words. Cweryl, cwestiwn, cwarel, are all bor-

rowed, and are as yet unnaturalised, and cwinc, a finch,

is dialectal.

In the following couplet from Edmwnd Prys—

I rannu hon ar onest,

Ni cheir cydwybod na chwest,'

the last word in its radical form may be either chwest

or cwest.

It is clear that the genius of the language rejects this

sequence. In fact Aryan qu, that is q velar after which

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6395) (tudalen 036)

|

36

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

a slight consonantal w was regularly developed, passed

into p in Brythonic. Compare Welsh pedwar, pump,

with Latin quattuor, quinque (see Sir John Rhys's Welsh

Philology). Words in qu borrowed into Welsh as they

become naturalised change q into ch, as

chwil and chwart, from English quill and quart.

C and the corresponding voiced sound g have two

values according to the part of the mouth concerned in

the articulation.

If the stoppage is between the ridge of the tongue

and

(i.) The back or soft palate, the sound is back or

velar, as in cwys, cwm: gwas, gordd.

(ii.) The front or hard palate, the sound is front or

palatal, as in cil, cig: gilydd, gerwin.

In Montgomeryshire and along the Merioneth coast

an extreme palatal value is given to these mutes before

a, with a consequent growth of a parasite i after the

thus in the above-named districts caws,

consonant:

cath, and gardd are pronounced ciaws, ciath, and giardd.

The same peculiarity is found in Gwentian, where for

example cant is pronounced ciant.

C AND T.

Now, if the stoppage is made by the tip instead of the

adjoining blade of the tongue, the sound produced is t

and not palatal c. The physiological difference is so

slight that one can easily understand why palatal c

and t pass so readily into each other. Indeed there is

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6396) (tudalen 037)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

37

abundant evidence that the transition from velar ' c

(' g ' or ' ch ') to the labio-dental ' t' (' d ' or ' th ') is

easy and of common occurrence. Thus in Latin we find

the doublets

juvencus and juventus:

novitius and novicius ,

while in Late Latin verbs the endings -itare and -icare

were frequently interchanged.

So, older English apricock is now apricot, though

probably here the change of ' c—c ' into ' c—t ' is due

in part to dissimilation.

In Welsh poetry -od and -og are sanctioned as correct

rhyme, e.g.,

Lle cyrch iyrchod, rywiog ryw,

Lle can edn, Ile cain ydyw. '—D. ab G. xix.

Interchange of—T (or D) and C:

D (or DD)

1. T (or D) AND C.

dyllhuan, tyllhuan and cylluan, cyrlluan ,

dyrchafael and cyrchafael:

Ascension Thursday is ' Duw leu Kyrchauel '

Brut y Tywysogion.'

ieuanc, ieuant, and iewaint:

'A'r cloyn a går yr ieuaint. '—Llywarch Hen.

in

(v. Pughe and Pryse's Dictionary, s.v. ieuant).

ysgol ( < Latin scala) and ystol.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6397) (tudalen 038)

|

38

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

chwilcath (vb. and noun) and chwiltath (verb).

Gwar gwrcath, gwydn chwilcath chwai.'

D. ab G. cexxx.

Pa beth sydd yna'n chwiltath ?

Tyngais i'm cyffais mai cath. ab G. clviii.

tywarch and cywarch.

For ' Glynn Cywarch ' see Bardd Cwsc, 54.

Tyddyn Cywarch ' is a farm near Llanfechell in

Anglesey.

The late Dr. Silvan Evans in his monumental dic-

tionary (see under Cywarch) enquires—

Can it be that cywarch, cywarchan, cywarchen

have originated in misreading c and t (tywarch, tywarch-

an, tywarchen), which are very like in old Mss. ?

While probably this suggested explanation has some

foundation in fact, it should be borne in mind that

the interchange of t and c is not confined to Welsh or

modern languages. Moreover, no such misreading

would account for the interchange of d and g (see below).

Ilosgwrn and Ilostwrn:

compare Ilostlydan, a beaver, and Cornish lost a tail

tlws and clws:

tlawd and clawd .

Clawd is the general pronunciation in parts of Gwy-

nedd (as in 141911) and also in Gwentian. Tl in the same

syllable involves a peculiar change of direction in the

emission of breath, and great mobility or muscular

activity in the tip of the tongue. The breath forces its

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6398) (tudalen 039)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

way out over the tip (t), which is then immediately

replaced, the air being passed laterally over the sides of

the tongue (l). The closely related sequence cl is much

easier, for after the stoppage between the back or

middle of the tongue and the roof of the mouth is forced

open (c), it is not difficult to bring the tip into contact

with the gums of the upper teeth so as to divert the

escaping breath over the sides

The change of tl (or dl) into cl is not peculiar to Welsh.

Latin very early turned medial -tl- into -cl- as in

Periclum, and probably English clever is from Middle

English deliver (

quick, active).

TH AND CH.

brith and brvch •

brithyll and (Gwentian) bryehyll •

dethe (Demetian) and decha (Gwentian) deheuig;

blith as compared with Eng. milk, Old Irish melg,

(For interchange of b and m see above).

3. D (OR T) AND G (OR C).

bwrdais and bwrgais, from Eng. burgess ,

eyfod alld cyfog:

Ae yna Ylngyuoe o bawp ar hyt y ty.'

'And then all in the house arose. '—Mab. 39.

Cyfog has now a specialised meaning.

cywyll (culture, tillage) and diwyll, diwyllio:

dillwng (to liberate, set free) and gollwng:

deor and gori

dweyd and colloquial gweyd •

pioden and piogen:

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6399) (tudalen 040)

|

40

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

Piogen occurs in Llyfr y Tri Aderyn, p. 229. There

is a Tyddyn Piogen in the parish of Holyhead, Piod is

common.

sudd and sug: see Lly/r y Tri Aderyn, p. 263.

Welsh softens final -c after a vowel into -g, except in

a few borrowed words which have not been completely

naturalised. Thus

Mediaeval rhac is now rhag, and English catholic is

catholig.

The preservation of ' ac,' and, and ' nac,' no, neither,

nor, side by side with ' ag,' ' nag,' is due to a conscious

effort to differentiate forms on account of difference of

function. This very desirable distinction is scrupu-

lously observed in present-day writings, but in works

of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries ' ag ' and ' nag

are frequently used for ac and nac. Thus in De,i/ynniad

Ffydd Eglwys Loegr by M. (1595),

ag ' is the

regular form used for and before vowels. Again Edward

Morus in Cywydd v Llwon Ofer writes

Buddiol, gweddol ag addas,

O bur gred i beri gras.

CH is a guttural spirant bearing the same relation to

c as Welsh f/ does to and th to t. It is somewhat

harder than the guttural in Scotch loch, Irish lough,

German nacht, and Old English liht. It may be

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6400) (tudalen 041)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

41

(1) an immutable radical as chwi, chwant, or

(2) a spirant form of c as tri chant.

As a radical initial it is invariably followed by w,

which is in some words nothing but a parasitic sound

heard as the tongue moves away from the ch position.

Further, this w is always consonantal except in the

word chwydd* (a swelling) and its derivatives. Com-

pare the consonantal value of u after q in English.

Indeed the Welsh initial chw- differs in phonetic value

from English qu only in that q is a guttural stop, while

ch is a guttural spirant. And as cw- is foreign to Welsh

(v. under C above) it is not strange that English qu-

words pass into Welsh under the form chw-.

For the same reason provected gw (consonantal)

passes into chw, as—

chware from gware

chwaen from gwaen ,

chwedi from gwedi •

chwysigen from gwysigen.

Now ch will readily pass into h if the back of the

tongue be not held so near the back of the palate as to

produce the friction heard in the former sound. And

that is exactly what takes place regularly in the radical

initial group chw- in Demetian. There chwant is pro-

nounced hwant, and chwaer is hwar. Chwi and its

derivative chwithau are exceptions, and retain even

in that dialect the full value of the ch, though it may be

mentioned in passing that the w is usually dropped, the

words being pronounced chi and chithe. The com-

* Consonantal w in Demetian.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6401) (tudalen 042)

|

42

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

pound chwychwi is not heard in that part of Wales

except in the very corrupt form ' y chi.'

Instances of hw- (or rather wh-, see below) occur in

Mediaeval works written in Demetian .

Gossot v deulu ar whech milltir o wastattir.'

Ystorya, 11.

Duw a talo itt vyg whaer heb y peredur. '—Mab. 220.

The same characteristic marks Gwentian, except that

in that dialect a further change is often made whereby

the spirant disappears altogether, thus—' whar ' or

war ' (the ' a ' having the same value as in English glad,

man), ' whech ' or ' wech.'

A similar change occurs in late Cornish and in Breton.

But why the spelling wh and not hw in the above

instances ? Etymologically hw would be more correct,

while phonetically the digraph stands for a simple

sound, and the aspirate comes neither before nor after

the w. A simple symbol would more accurately repre-

sent the sound, or, failing that, a mark of aspiration

over the w as in Greek. The reason for the changed

order is two-fold

(1) The analogy of ph, rh, and the

(2) An idea prevalent in Mediaeval times that the

digraph represented two distinct sounds, and that the

aspirate followed the w. A similar mistake accounts

for the change of Old English ' hwa ' into Middle Eng-

lish ' who.'

Just as chw- in South Welsh passes into wh, the re-

verse process may be and is resorted to in order to give

a word a more distinctly Welsh sound and appearance.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6402) (tudalen 043)

|

WELSH

PHONOLOGY.

Thus English words in wh- are borrowed into Welsh

under the form chw-, as—

chwip from Eng. whip

ehwirligwgan from Eng. whirligig ,

ehwisgi from whiskey.

It is a natural corollary that there are no words in

Standard Welsh to-day beginning in hw or wh. In the

few words in hw-, tv is invariably a vowel, as—

hwy, hwyl.

No words outside the dialects begin in wh.

Any enquiry then into the origin of radical ch- and

chw- Illust take note of the Illany avenues along which

words containing these sounds have come to their pre-

sent form.

Thus chwysigen is borrowed from Latin vesica,

through the intermediate form gwysigen, where the g

itself is prosthetic, and therefore not an organic part of

the word. In Chwefror the chw is from the s of mis and

the / of Latin Fcbruarius, the s passing into ch through

the intermediate h. Similarly chwech goes back to a

hypothetical Aryan sueks, a doublet of seks which is the

parent of English six and Latin sex. Hence W. chwech,

Eng. six, and Latin sex are all cognate. As in the case

of h (see below), radical ch may often be referred to

Aryan s. (For secondary ch see chapter on Mutations.)

Ch in chwip is from the inorganic h in English whip.

It. was stated above that Old English had a guttural

spirant which was represented in writing by h, as—

liht ' (modern light), ' broht' (

brought) ,

neah

nigh), ' heah ' ( = high), ' hreoh ' ' ruh ' (

rough) ,

hleahhan

to laugh), ' hoh hough).

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6403) (tudalen 044)

|

44

WELSH PHONOLOGY,

The Mediaeval scribe, who sought to spell the English

of his day phonetically, represented the guttural spirant

by the nearest digraph at his command, that is by gh,

just as successfully as the Welsh scribe who adopted ch

for the parallel but more surd Welsh sound. Of course,

the limited number of symbols in either alphabet made

a more accurate representation impossible, unless the

bold (and better) step were taken of coining or borrow-

ing new symbols for these individual sounds. It is true

that in neither language did the digraphs have the

separate values of their component parts: that is, gh

in ' brought ' at no time in its history had the value of

g + h ' in ' big horn,' nor was ch in Welsh chwi in-

tended to represent the distinct sounds heard in ' ac

hefyd.' But just as the Greek aspirated t, p, c—that is,

theta, phi, and chi

in the post classical period became

continuants, so had English ' p-h ' and t-h ' passed

into the spirants or continuants ph (

f) and th ( =th

in thin, this). Hence Mediaeval orthographists in adopt-

ing gh (in English) and ch (in Welsh) as symbols for the

guttural continuants in those languages were only

extending a principle already recognised in the case of

ph and th.

The reader will not fail to notice another instructive

parallel between English and Welsh in the development

of the parasite u in Inost instances before the guttural.

As in the case of the tv in Welsh awch (Y'our), uwch

(higher), &c., the guttural vowel sound is somewhat

inevitably produced as the tongue takes up its position

for the articulation of the guttural spirant. This is

especially the case after a back or low vowel like ' o

or ' a.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6404) (tudalen 045)

|

Further, just as in South Wales ch in ' chw ' has allnost

everywhere passed into h, so even in Old English h at

the beginning of a syllable was a simple spirant as in

Modern he, has. Hence while the second h in Old Eng.

heah passed into Middle English gh, the initial h remained.

In Modern English the guttural ' gh ' sound has dis-

appeared. The muscular effort involved in its articula-

tion was found too severe, and either the sound was

dropped with compensatory lengthening of the vowel as

in though, high, Vaughan (< W. Fychan), or it was

changed into the more easily produced labio-dental

spirant f as in laugh, rough, Gough ( < W. Goch) .

No such difficulty has been experienced in Welsh

except initially as mentioned above—and the inter-

change of ch and ff is not common. Dichlais and difflais,

safe, secure, may be an illustration, but even if they are,

? di,

the change is probably from the f/ of difflais (

not + flexus, bending) to the ch of dichlais.

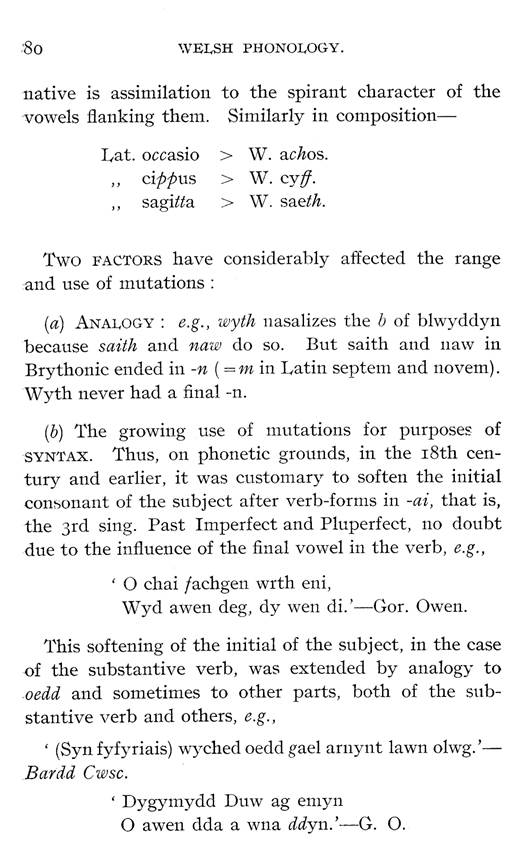

D.

D is a dental sonant of which the corresponding spi-

rant is dd ( = th in English then), just as th is the corres-

ponding spirant to the dental surd t. The inter-relation

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

t.

45

therefore of these

sounds may be expressed by the

formula

or again

D-t >

dd

th

th.

st > s:

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6405) (tudalen 046)

|

46

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

The change of ' d—t ' into ' s ' in ' llas

a form once

common for the aorist Impersonal ' lladdwyd,' ' lladded '

is a striking case of dissimilation. In early Welsh

d—t,' in lladt, a short doublet of lladded, lladd

wyd, came too near together to be distinctly and

separately articulated: the mobility of the tip of the

tongue was not equal to the task. Hence an attempt

was made to articulate the ' d ' by bringing the adjoin-

ing blade of the tongue into contact with the palate,

leaving the tip free for the immediately succeeding ' t.'

But that division of labour of necessity yielded ' s t,'

and eventually the s assimilated or eclipsed the t:

llad-t > llast > llas.

The same result is familiar to us in the English ' Inust

and ' wist,' and in Latin ' est,' he eats. ' Must ' is from

A.S. ' moste

(for mot-te) the preterite of ' mot,' and

wist ' ( < wit-te) is the preterite of ' wit,' still used in

to wit.' ' Est ' is for ' ed-t ' a doublet of edit from edo.

The same process of dissimilation will probably ex-

plain ' Wstrws,' the nan-me of a large house near Capel

Cynon, on the road between Llandyssul and New Quay,

in Cardiganshire. The origin of the natne has been the

subj ect of much discussion at different times.

It

seems likely to be nothing but a modified form of

Wyth-drws,' just as ' wythnos ' is pronounced ' Wsnos

in Anglesey and other parts of Wales. For such a name

as ' Wyth-drws ' compare ' Saith-aelwyd,' a farm by

Llangefni.

Di > Dzh

Di,' when followed by a vowel, tends to acquire the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6406) (tudalen 047)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

47

dzh ' sound heard in English judge, gin. In formal

speech this change is not countenanced, due partly to

the fiction that Welsh words are spelt phonetically, and

that therefore per contra they should be pronounced as

they are spelt. But colloquially diogel and diofal are

approximately dzhogel and dzhofal, while only a minc-

ing pronunciation of ' diawl ' in colloquial speech would

differentiate the sound from that in ' dzhawl.' Com-

pare the pronunciation of t in English nature and similar

words.

Dd is the soft mutation of d, and is never met with as

a radical initial in Welsh (cf. chapter on Initial Muta-

tions).

For inorganic dd and lost dd see sections below de-

voted to excrescent and lost sounds.

Final dd after a vowel is apt to be hardened into d,

thus, while gormodd has literary sanction, e.g.,

Marw mab mam, mawr ymhob modd,

Mair a Gannon ! marw gormodd. '—Tudur Aled,

G.B.C., 230.

and is still used colloquially in Gwentian, gormod is

the recognised literary form to-day. Similarly machlud

(from ym + Latin occludo) is for an older form ymach-

ludd, while ansawdd has been kept by the side of

ansawd, but with differentiation of meaning.

N tends to harden dd into d, as bendith from benddith.

F and Ff.

Both are labio-dental spirants, f being voiced like

English v, or f in of, and the corresponding voiceless

sound like f in English for.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6407) (tudalen 048)

|

48

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

Initial F- does not occur in the radical or dictionary

form of a word, except

(1) by Aphaeresis, as ' fel ' < ' fal ' < hafal.

(2) by crystallization of a mutated form as the radical,

as TV, /y. In many instances this is due to the habitual

use of the definite article ' y ' with the word, as (y)

fagddu, (y)fory.

(3) In a few borrowed words which have resisted

provection into m- or b-, due to the influence of the

familiar original spelling, as finegr, fernlilion.

DD AND F.

The interchange of the voiced spirants / and dd is

common, due to the ease with which the vocal organs

can pass between the two positions concerned in their

articulation, If the tongue be dropped from the dd-

position, the lower lip is readily brought into contact

with the upper teeth yielding f, while again the

dropping of the lip is often accompanied by the raising

of the front and tip of the tongue. Examples .

Afanc and addanc:

Ac wynteu a dywedassant bot adanc mywn gogof. '

Mab. 224.

Balwyf and balwydd .

Balwydd is probably to a great extent due to a

fancied connection with gwjdd.

Cufigl and cuddigl.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6408) (tudalen 049)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

Caerdyf and Caerdydd

49

Etymologically the word denotes the caer on the

river Taff (Welsh Tåf), though there is a local tradition

that it denotes the caer of Aulus Didius.

A'm bod er's talm, salm Selyf,

V n caru dyn uwch Caerdyf.'-—D. ab G. Il. (p. 3).

Eifionydd and Eiddionydd

eddain

edryd

efain

edryf •

ach ac edryd (or edryf),' stock and lineage.

godwrdd, dadwrdd, godwrf, tarfu, cynnwrf

gwyryf, gwyrydd, and adwerydd

gwyddon and gwyfon

hwyfell

hwyddell

lladd and cyflafan:

llawryf and llawrwydd.

For llawrwydd compare balwydd above.

nwyddau and nwyfau •

plwyf and plwydd.

We may also compare rhudd and English ruddy with

Rufus and rubric.

The corresponding voiceless th and are not nearly

as often interchanged, for the muscular tension required

for their articulation in the vocal organs is unfavourable

to the necessary fluidity. Still examples do occur:

The 3rd Sing. Pres. Indic. termination of verbs is

-ith in Demetian, -iff in Gwentian, as rhedith,

rhediff, runs ,

benthyg is a corruption of benffyg

4

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6409) (tudalen 050)

|

50

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

and pencnath (N. Wales), penneth (S. W.) are common

pronunciations of English Penknife. Similarly English

children sometimes say ' nuffink ' for ' nothing,' and

some always pronounce ' three ' as ' free.

DD AND TH.

Dd in an energetic articulation may easily pass into

th, and on the other hand a languid pronunciation may

reduce th into dd:

arglwydd and arglwyth

colwydd and golwyth

cynysgaeth and cynysgedd

diwaethaf and diweddaf '

(gwen)ith and yd •

Old Ir. ith corn: compare English te'heat — the white

grain.

wmbredd and wlllbreth.

We may conmpare the voiceless ' th ' often heard in

the articulation of ' with ' in English, when special

emphasis is laid upon it: also the emphatic adverb

off ' and the weakened preposition ' of.'

The adjoining ' n ' accounts for the unvoicing or

hardening of the ' dd ' in

(1) ganthaw, gantaw: ganthi, genti (common in the

Mabinogion), from ganddo: ganddi.

(2) Mediaeval ganthunt and gantunt for ganddunt

(—Modern ganddynt, the u > y on the analogy of the

3rd plu. Past Impf. and Plupf. of verbs):

' A diheu oed ganthunt na welsynt eiryoet gwr a march

ac arueu hoffach gantunt eu meint noc wynt. '—Mab,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6410) (tudalen 051)

|

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

F ( = V), AND OR U.

51

The interchange of the voiced spirant ' f ' and ' w,

whether vocalic or consonantal, is one of the best at-

tested facts in Welsh phonology. In value the ' w ' is a

vocalised f, as in

awrddwl fronm afrddwl

evwoed fronn cvfoed.

Further, the softening of the labials ' 111 ' and ' b

may follow one of two lines:

(1) the lower lip Inay be

brought into gentle contact with the upper teeth, allow-

ing a mild escape of breath. The resulting sound is f

v). Or (2) with equal ease the tension may cease in

the lips, which will then be held loosely together, and,

due to the gentle pressure of the breath in the resonance

chamber behind, they will be pushed forward: the

back of the tongue will at the same time be raised as an

autonaatie accompaniment: the resulting sound is ' w.'

Thus the Welsh cognate of Old Irish ' cumachte,' and

of English ' lilight,' assunnes the doublet forms

cyfoeth and cvwaeth.

Cawn o ddawn a eiddunwyf,

Cyzcyae(hog ac enwog wyf. ab G. iii.

and the ' b ' seen in Old Irish Serb, delb, marb, tarb, &c.,

is ' w ' ill their Welsh cognates chwerw, delw, marw,

and tarw.

The change of ' w' or ' u ' into ' f

is sometimes

fanciful and due to false analogy, as,

yntef for yntau:

Ac yntef oedd yn eistedd yng-hanol y llwch. '—Llyfr

Job, ch. ii.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd F6411) (tudalen 052)

|

52

WELSH PHONOLOGY.

and, anghefol for angheuol .

(Fel) y nessao ei enaid i'r clawdd: a'i fywyd i _-loes-

ion] anghefol. '—Llyfr Job, xxxiii.

Other examples of the interchange of ' f,' and w,

u ' are—

archfa for arehwa .

archfa'r bwydydd.' Bardd Cwsc, 23.

berfa, from Old. Eng. berewe:

colloquial bregwast or brecwast, fronl Mod. Eng.

breakfast.

criafol and criawol

cenafon and cenawon

cleddyf and cleddau •