kimkat0996e A short description of the Gwentian dialect, c. 1895, by

Joseph A. Bradney, Tal-y-coed, Gwent. “The Welsh language is practically dead

in this district, which fact will perhaps make the preservation in print of the

local pronunciation of some value. I lay no claim to a scientific knowledge of

the language and merely give the words that in my youth I was accustomed to

hear.”

01-08-2018,

http://www.theuniversityofjoandeserrallonga.com/kimro/amryw/1_gwenhwyseg/gwenhwyseg_the_gwentian_dialect_bradney_1895_0996e.htm

0001z Yr Hafan / Home Page

..........1864e Y Fynedfa yn Saesneg / The

Gateway in English

....................0010e Y Barthlen / Siteplan

............................0223e Y Gymraeg / The Welsh

Language

.......................................1004e Y Wenhwyseg - Y Tudalen Mynegeiol / The Gwentian

Dialect - Index Page

..............................................Y

Tudalen Hwn / This Page

|

|

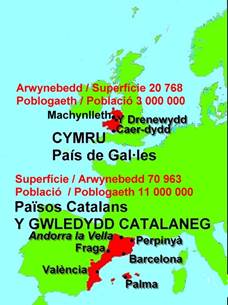

Gwefan Cymru-Catalonia Y Wenhwyseg

(tafodiaith y de-ddwyrain) |

|

1/ Text with added comments ( In brackets, in

orange type, I have added comments).

2/ For the original text, without comments, see the version in red print

at the end of the page)

Bradney, Joseph A (Tal-y-coed, Gwent.) 1921 The Gwentian

dialect Archaeologia Cambrensis 76, 145-146.

_____________________________

The Gwentian Dialect

The notes by the Editor (Sixth Series, Vol. XX, p286) on dialects and local forms

of speech and pronunciation induce me to offer a few observations on the speech

of the old inhabitants of Gwent. The Welsh language is practically dead in this

district, which fact will perhaps make the preservation in print of the local

pronunciation of some value. I lay no claim to a scientific knowledge of the

language and merely give the words that in my youth I was accustomed to hear.

_____________________________

One of the most unusual intonations is to employ t instead of d in

many words, as

Oty mae e for ydyw;

nac ote for nag ydyw

ffetog for ffedog (apron), &c.

_____________________________

The plural of words such as mab, dyon, is meibon, dynon.

_____________________________

Other words are:-

(The author notes in a footnote: “A star is

placed against those words noted in the article alluded to above”, that is, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Sixth Series, Vol. XX, p286)

*Wado, to beat.

Mentig, a loan; rhoi mentig, to lend. (“give a loan”)

*Lletiaith (llediaith) for accent, as when a man speaks English

with a Welsh accent, and vice versa.

Taclau, harness.

*Pwtwr, lazy. (pwdr = rotten;

lazy)

*Rhaca, a rake; rhaca-troi. to rake-turn the hay.

*Siwrna, a journey. (siwrnau =

journey)

Shimla, a chimney. (shimnai =

chimney)

Cyffylau gwaith, cart horses, as opposed to nag horses. (Literally: horses (of) work)

*Eifed, ripe; as, mae’r ’falau yn eifed. (aeddfed = ripe; mae’r afalau yn aedfed = the apples are

ripe)

Danant, nettles. (danadl).

*Cered, to walk. (cerdded = to

walk)

Rheteg, to run. (rhedeg = to run)

*Gryndo, to hear. (gwrando = to

hear)

*Gwddwg, neck. In “Parochalia,” by Edward Lhwyd (II, 36), the

waterfall in the parish of Llanfihangel Nant Melan, Radnorshire, called

nowadays Water Break its Neck, is said to be “yn torri i gwddwf.”

[Perhaps, however, the last letter f is a misreading for g.] (gwddf = neck; in the north, gwddwf > gwddw; in the

south, gwddwg)

*Gwinedd, finger nails. (gwinedd

< winedd < ewinedd)

Rhetig, to plough, for aredig.

*Mwrthwl, a hammer.

Gweitho for Gweithio. (gweithio

= to work)

Clwyd, a gate, clwyd dwy droed, a hurdle.

Ty cwrdd, a meeting house, signifying the nonconformist chapel as

opposed to the church (eglwys). ((a)

house (of) meeting)

Clawd for tlawd. An old saying of the parish of Goitre (= Y Goetre), which has a poor, hungry soil,

is

Goitre glawd

Heb na bara na blawd.

(poor Goetre, with neither bread nor flour)

Dau, two, pronounced dou.

Hicen, twenty (ugain).

Buwch, a cow; the plural is always gwartheg (cows);

da, cattle in general.

Cymdogion for cymdeithion. (cymdogion

= neighbours, cymdeithion = fellow travellers)

Iaca for ia (ice). (iâ = ice)

Doti for dodi; doti coed, to plant trees. (dodi = to put, to place)

Kind, for well or good, as mae’r coed bach yn tyfu yn gind.

(standard spelling ceind; the little trees are

growing well)

Crefa, for cryfau, as mae’r moch bach yn crefa. (the little pigs are growing)

Beili, the fold or yard of a farm house. [Latin ballium]

The third person singular of the prefect tense is often ws instead of

oedd (in fact, -odd), as fe wetws

wrtho i (he told me).

Rhyng for rhwng. (between)

Rhw for rhy (too), as mae’n

rhw oer i fynd i maes. (it’s too cold to go

out)

Drys for tros, as drys y bont. (over

the bridge)

Worlod for gweirglawdd, as worlod glan Toddi (the

meadow by the side of the Trothy)

Ffwrwm, a bench. At Machen is an inn is Y ffwrwm ishta (eistedd),

so called from an ancient bench outside the house. (y

ffwrwm ishta / Y ffwrm eistedd = the bench (of) sitting)

Rit yr heol for ar hyd yr heol (along

the road)

Yn glau (pronounced gloy);

as rhetwch yn glau (run quickly)

Anghommon (= anghomon)

for anghyffredin; as wy’ yn lico seidr yn anghommon (I like cider

uncommonly). At the election of 1886 political arguments took place; an old

man, a great Liberal, used to end the discussio by saying, “Wel, wel, wy’ yn

lico Mr. Gladstone yn anghommon, with great stress on the penultimate syllable”.

Cascen, a cask or hogshead. (=

casgen)

Cladde, mantelpiece; the gun was kept in a rack uwch y cladde.

cwtch (cysgu) (in fact, not

connected with Welsh cysgu = to

sleep; from Middle English < Old French coucher, lie down), used

only in English; a man orders his dog to go cwtsh in the cornel.

Crwtyn, a boy; in English, the phrase is often used a crot of a

boy, meaning a very little fellow.

Meillion, the Dutch clover; the common clover is called by the

English name.

Gwas y neidr, dragon fly.

The bells of

Gwadd, mole; but in English the mole is always called locally an wnt.

Costrel, used in Welsh and English for the wooden bottle

containing cider.

_____________________________

Some of the above words are used all over Wales; some are peculiar to Gwent,

and some may be considered as mere Anglicisms, as may be expected in a district

so near to the English border. It would apprear to me that the Welsh in the

life of St. David (“Cambro-British Saints,” p. 102) very nearly represents the

Gwentian form of the language.

_____________________________

Footnote: *A star is placed against those words noted in the article alluded to

above

(The article referrred to is in Archaeologia

Cambrensis, Sixth Series, Vol. XX, p286)

_____________________________

Tal-y-coed, Gwent.

JOSEPH A. BRADNEY

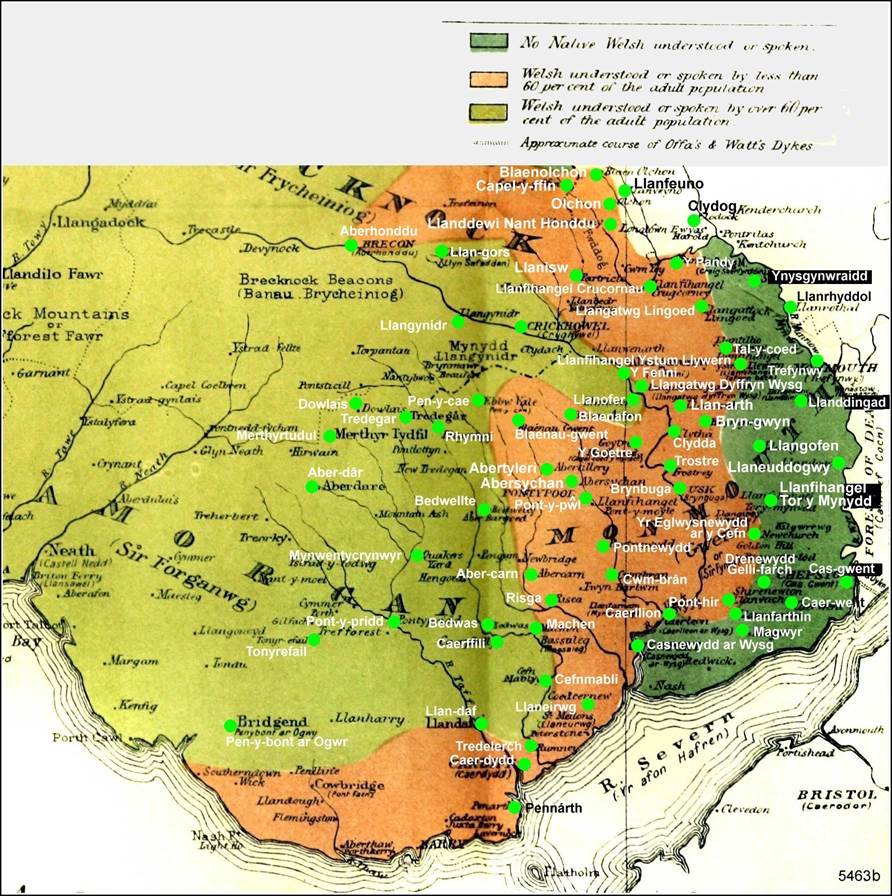

(Tal-y-coed SO4115, 7km north of Rhaglan, 11km west of Y Fenni and 10km

east of Trefynwy, on the Y Fenni - Trefynwy road)

(delwedd 5463b)

Tal-y-coed is west of Trefynwy / Monmouth, at the top

right-hand side

ORIGINAL TEXT

The Gwentian Dialect

The notes by the Editor (Sixth Series, Vol. XX, p286) on dialects and local

forms of speech and pronunciation induce me to offer a few observations on the

speech of the old inhabitants of Gwent. The Welsh language is practically dead

in this district, which fact will perhaps make the preservation in print of the

local pronunciation of some value. I lay no claim to a scientific knowledge of

the language and merely give the words that in my youth I was accustomed to

hear.

One of the most unusual intonations is to employ t instead of d in many words.

as

Oty mae e for ydyw;

nac ote for nag ydyw

ffetog for ffedog (apron), &c.

The plural of words such as mab, dyon, is meibon, dynon.

Other words are:-

*Wado, to beat.

Mentig, a loan; rhoi mentig, to lend.

*Lletiaith (llediaith) for accent, as when a man speaks English

with a Welsh accent, and vice versa.

Taclau, harness.

*Pwtwr, lazy.

*Rhaca, a rake; rhaca-troi. to rake-turn the hay.

*Siwrna, a journey.

Shimla, a chimney.

Cyffylau gwaith, cart horses, as opposed to nag horses.

*Eifed, ripe; as, mae’r ‘falau yn eifed.

Danant, nettles. .

*Cered, to walk.

Rheteg, to run.

*Gryndo, to hear.

*Gwddwg, neck. In “Parochalia,” by Edward Lhwyd (II, 36), the

waterfall in the parish of Llanfihangel Nant Melan, Radnorshire, called

nowadays Water Break its Neck, is said to be “yn torri i gwddwf.”

[Perhaps, however, the last letter f is a misreading for g.]

*Gwinedd, finger nails.

Rhetig, to plough, for aredig.

*Mwrthwl, a hammer.

Gweitho for Gweithio.

Clwyd, a gate, clwyd dwy droed, a hurdle.

Ty cwrdd, a meeting house, signifying the nonconformist chapel as

opposed to the church (eglwys).

Clawd for tlawd. An old saying of the parish of Goitre,

which has a poor, hungry soil, is

Goitre glawd

Heb na bara na blawd.

dau two, pronounced dou.

Hicen, twenty (ugain).

Buwch, a cow; the plural is always gwartheg (cows);

da, cattle in general.

Cymdogion for cymdeithion.

Iaca for ia (ice).

Doti for dodi; doti coed, to plant trees.

Kind, for well or good, as mae’r coed bach yn tyfu yn gind.

Crefa, for cryfau, as mae’r moch bach yn crefa.

Beili, the fold or yard of a farm house. [Latin ballium]

The third person singular of the prefect tense is often ws instead of

oedd , as fe wetws wrtho i (he told me).

Rhyng for rhwng.

Rhw for rhy , as mae’n rhw oer i fynd i maes.

Drys for tros, as drys y bont.

Worlod for gweirglawdd, as worlod glan Toddi (the

meadow by the side of the Trothy)

Ffwrwm, a bench. At Machen is an inn is Y ffwrwm ishta (eistedd),

so called from an ancient bench outside the house.

Rit yr heol for ar hyd yr heol

Yn glau (prnounced gloy); as rhetwch yn glau (run

quickly)

Anghommon for anghyffredin; as wy’ yn lico seidr yn

anghommon (I like cider uncommonly). At the election of 1886 political

arguments took place; an old man, a great Liberal, used to end the discussio by

saying, “Wel, wel, wy’ yn lico Mr. Gladstone yn anghommon, with great stress

on the penultimate syllable”.

Cascen, a cask or hogshead.

Cladde, mantelpiece; the gun was kept in a rack uwch y cladde.

cwtch (cysgu) , used only in English; a man orders his dog

to go cwtsh in the cornel.

Crwtyn, a boy; in English, the phrase is often used a crot of a

boy, meaning a very little fellow.

Meillion, the Dutch clover; the common clover is called by the

English name.

Gwas y neidr, dragon fly.

The bells of Welsh Newton Church are said to sing, Erfin, cawl erfin,

the people being so poor that they had only turnips to eat.

Gwadd, mole; but in English the mole is always called locally an wnt.

Costrel, used in Welsh and English for the wooden bottle

containing cider.

Some of the above words are used all over Wales; some are peculiar to Gwent,

and some may be considered as mere Anglicisms, as may be expected in a district

so near to the English border. It would appear to me that the Welsh in the life

of St. David (“Cambro-British Saints,” p. 102) very nearly represents the

Gwentian form of the language.

Tal-y-coed, Gwent.

JOSEPH A. BRADNEY

Adolygiad

diweddaraf - latest update: 01-08-2018, 19 07 2000

Ble’r wyf i? Yr ych chi’n ymwéld

ag un o dudalennau’r Gwefan “CYMRU-CATALONIA” (Cymráeg)

On sóc? Esteu visitant una pàgina de la Web

“CYMRU-CATALONIA” (=

Gal·les-Catalunya) (català)

Where am I? You

are visiting a page from the “CYMRU-CATALONIA” (= Wales-Catalonia) Website (English)

Weø(r) àm ai? Yùu àa(r) víziting ø peij fròm dhø “CYMRU-CATALONIA” (= Weilz-Katølóuniø) Wébsait

(Íngglish)

CYMRU-CATALONIA