|

|

…..

.....

.....

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1580)

(tudalen 50)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

50

PHONOLOGY

§41

occasionally with different meanings, as ymladd 'to fight', ymladd 'to tire

one's self; ymddwyn 'to behave', ymddwyn,

' to bear'.,

Y dydd a'r aw, ni'm dawr, dod ;

ymwel A mi dan dmod.—G.I.H., TB. 91.

' Fix the day and hour, I care not [when]; visit me under [that]

-.condition.' • Arthur o'i ddolur oedd wan, Ac o ymladd '•ad Gamlan.—L.Q.Q.

450. , _»

' Arthur •was weak from his wound, and from; fighting the battle of Camlan.'

See also T.A., c. ii 78.

Y fn'rcJi weddw ddifrycheuddeddf Wcdi'r ymladd u'r drem leddf.—D.E., s

112/840.

' The widowed woman of spotless life after the prostration and disconsolate

aspect.'

ii. The reduplifiitod pronouns my ft, tydi, etc. Rarely these are

accented regularly; HOC § 1^9 ii (l).

iii. (l) Words in which the last syllable has a late contraction, § 33, such

as pa\ra\t6i for Ml. W. pa\ra\toi 'to prepare', cy\tun for Ml. W. ci]\tw wi '

united ', Gwr\l,hvi/rn for Qwr\t1ie\'i[rn, Cf'm\raeg for Cyn\rd eg, pa\rhad

for pa\rha\ad 'continuance '. It is seen that in these words the accent in

Ml. W. was regular, and kept its position after the ultima was merged in the

penult.

(a) In the word ysgolfidig, Ml. W. yscolheic ' scholar', the contraction in

the last syllable seems to have taken place early in the Ml. period, as Nid

vid iscolheic nid vid eleic unhen, B.B. 91 (10 syll. ; read smiA/ieic, ^ 23

ii), but it was necessarily subsequent to the fixing of the present accentuation

; in B.TI. 81 the uncontracted form occurs, rh. witli gitledic. A niinlhir

form is pea-dig ' chief. , The wOTdjfelazy seems to have boon accented

regularly ; thus in,. B.P. iaai we have ffeleic /ffiliji the latter being the

J-iat.filii.

Tudur waed Tewdwr ydoedd, A phenaig cyff' leuan oedd.—G.u.O., 0. 196.

' He was Tudor of the blood of Tudor, and chief of the stock of

leuan.'

«

iv. A few words recently borrowed from English; as apel, ' appeal'.

§42

ACCENTUATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1581)

(tudalen 51)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

51

v. Disyllables in which h stands between two vowels are accented regularly;

thus cyhyd as in Cyhyd a Thai og hdearn D.G. 386 . ' [spikes] as long as

those of an iron harrow'; and hyd gyhyd C.O. 312 'full length'; cyhoedd '

public', as in gyhoedd/gdeat, B.P. 1283;

gweheirdd D.G. 20 'forbids '. Contraction has taken place in some of these,

thus cyhoedd > *c6hoedd > coedd, D.G. 524; so gwdhan > giodn, which

gave rise to gwahan. This appears to be the reason for gwah&n, cyhyd,

gwahdrdd, etc. in recent W.

§ 42. In Ml. and early Mn. W. final w after d, 8, n, l, r, s was consonantal,

§ 26 iv; thus meddw 'drunk', marw 'dead', delw ' image', were monosyllables,

sounded almost like meddf, marf, delf. Hence when a syllable is added the w

is non-syllabic for the purposes of accentuation ; thus meddwon ' drunkards',

marwol' mortal', marwnad ' elegy ', clelwau ' images ', arddelw ' to

represent, to claim'. The w is usually elided between two con-' sonants, as

medd-dod ' drunkenness', for meddwdod. In B.B. 84 we have uetudaud

('=fehwdawd), but in Ml. W. generally such words were written without the w,

as mebdawt, E.P. 1217, i245> 1250, 1269, IL.A. 147 ; gwebdawf B.T. 31,

B.P. 1261 ' widowhood '. ' The w inserted in these words in recent

orthography is artificial, 'and is commonly misread as syllabic w, thus

medd\w\dod, the accent being thrown on the ante-penult, a position which it

never occupies in Welsh. The correct form medd-dod is still the form used in

natural speech. When final, in polysyllables, the •w is now dropped, and is

not written in late W., so there is not even an apparent exception to the

rule of accentuation; thus . arddelw ' to claim ', syberw ' proud ' are

written drddel, syber. In vwdrcJiadw ' to guard', ymoralw ' to attend (to)',

metathesis took place about the end of the Ml. period, giving gwdrchawd,

ym6r-}dwl, which became gwdrcfiod, ym6rol in Mn. W.

In all standard cynghanedd the w in these words is purely non-syllabic :

Da arSelw kynnelw KynSelw MinSawn.—E.P. 1229 (9 syll.) 'A good representation

of the exemplar of Cynddelw exquisitely gifted.' The accentuation of KynSelw

corresponds to that of JcemSavm. Cf. Aymrc/t / kyfenw, 1230.

^ I llorf am pair yn ll-^yrfarw

0 hud gwir ao o hoed garw.—D.G. 208.

' Its [the harp's] body makes me faint away from real enchantment and sore

grief.' ,

E3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1582)

(tudalen 52)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

52

PHONOLOGY

§ 42

Dyn marw a atlai f'drwain Weithian drwy eithin a drain.—D.I.D., G. 182.

' A dead man might lead me now through furze and thorns.'

Fenaid hoen geirw afonydd, Fy nghaniad dy farwnad f^'Id.—TLi.O; V.TS. 30.

' My beloved of the hue of the foam of rivers, my song thy dirge shall be.''

Cf. i farwnad efo D.I.D., o. 184. ,;' Marwnad ym yw awr yn d'6l.—T.A., A

14894/35. ' It is a lament to me [to live] an hour after thee.'

Pwy a'th eilw pe d'th wayw onnl—T.A., A 14975/102. '.Who will challenge thee

if with thy ashen spear"i'

The last example shows that eilw could still be a pure monosyllable at the

end of the igth cent., for the present disyllabic pronunciation .mars the

cynghanedd. Even stronger evidence is afforded by the accentuation deu-darw /

dodi B.Ph.B., Stowe 959/986. Although final W was non-syllabic, yn or yr

following it was generally reduced to 'n or 'r, being combined with the w to

form vm or wr, § 26 iii.

A'ch gwaed, rhyw ywch gadw'v hisol.—T.A., A 14965/46, ' With your blood it is

natural to you to guard tlie road.'

Mwnio da, inarw'Td y dizcedd.—D.IL., r. 31. ' Stowing away wealth, [and]

dying in tlie end.'

In a compound like marvmad the w was not difficult, for wn (rounded n) is

common in Welsh, § 26 iii. But the colloquial pronunciation is now mawrnad,

with metathesis of w. In i6th and i7th cent. MSS. we also find marnad and

barnad. The combination is more difficult in such compounds as derwgoed

'oak-trees', mdrwddwr 'stagnant water', ohwerw-der ' bitterness'; and though

tlie etymological spelling persisted in these, the pronunciation der-goed,

mdr-ddwr, chwer-der is doubtless old.

Lie d'vrgel gerllaw derwgoed.—D.G. 321. 'A secret place near oak-trees.' Cf.

dwwgist, T.A., G. 232.

Fro fy chwer'der yn fclysdra.—Wms. 657. ' Turn my bitterness into sweetness.'

—

Gyr chwerwder o garchdrdai;

Newyn y lleidr a wna'n llai.—D.W. 112.

' [Charity] drives bitterness from prisons; it makes less the hunger of the

thief.'

NOTE i. The rule that such words as marw, delw are monosyllabic was handed

down by the teachers of cynghanedd, but the bards of the 19th cent. hardly

knew what to make of it. Thus R.G.D. 97 uses marw and delw, und E.F. 185 uses

enw and garw as monosyllables, while at the same time rhyming them. They no

more rhyme as

§43

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1583)

(tudalen 53)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

53

ACCENTUATION

monosyllables than if they were marf, delf, or enf, garf. In standard

cynghanedd, marw rhymes with garw, tarw only, and delw with elw, gwelw only ;

see below. The disyllabic pronunciation may be traced as far back as the i5th

cent. In a couplet attributed to D.G. (see D.G. 322) bw rhymes with galw, a

rhyme condemned by S.V. because galw is a monosyllable whose vowel is a,

P.IL. xcii.

Some old rhymes are syberw/hirerw/derw/chwerw, B.B. 69 ; agerw/

chwerw/syberw/gochwerw, B.A. 19 ; helw/deJw, ib. ; dyveinw/dyleinw, B.T. 21;

divanw/llanw, M.A. i 475; ymoralw/salw, do. 466; cadw/ achadw/bradw, I.G. 422

; enw/senw, do. 407 ; geirw/teirw, D.G. 5°°'5 syberw/ferw, E.P. 203.

NOTE 2. In hwnnw, acw (earlier raccw') the w was vocalic; also probably in

other forms in wliicli it is a reduction of -wy, see § 78 i (2).

§ 43. i. No Welsh word or word fully naturalized in Welsh is accented on the

ante-penult. Such forms as Sdesoneg, Sdesones are misspellings of Sdesneg,

Sdesnes.

A'r gyfreith honno a droes Alvryt vrenhin o Gymraec yn Saesnec B.B.B. 79 'And

that law did king Alfred turn from Welsh into English.' See ib. 64, 95, 96,

etc.

The following words for different reasons are now sometimes wrongly accented:

catholig, omega^ penigamp 'masterly', periglor 'parson', lladmerydd '

interpreter', ysgelerder ' atrocity', oUwydd ' olives'.

A tMlu'rffin gath61ig.—S.C. 'And to pay the catholic fine.' Cf. c.o. 25; I.G.

491; L.M., D.T. 196.

Cyngor periglor eglwys.—M.R., F. 12. ' The counsel of a church parson'.

Pendig y glod, penigamp— • Penned i chompod a'i champ.—M.B. (m. D.G.), A

14967/183.

' Master of the [song of] praise, supreme—the height of its compass and

achievement.'

Alpha ac Omega mdwr.—A.E. (1818), E.G. p. xiii. 'Great Alpha and Omega.' Of.

IL.M. 2. See Wms. 259, 426, 869.

ii. A few words recently borrowed from English are accented on the

ante-penult, as melodi, philosophi; but derivative forms of even these are

accented regularly, e.g. melQdaidd, philosophydd.

This word has been naturalized in

Welsh as in other languages, and the natural Welsh pronunciation is probably

nearer the original than the tmega now sometimes heard from the pulpit in

imitation of the English fashion. The adjective is not an enclitic in Si

fiffa. The natural accentuation, as used by the hymn-writers, is

unconsciously adopted by those like A. Roberts who are not affected by a

little learning. '

'M.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1584)

(tudalen 54)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

54

PHONOLOGY

§ 44

§ 44. i. In a regularly accented word of three syllables the first syllable

is the least stre&sed; thus in can w\dau the stress on can is lighter

than that on dan, both being unaccented as compared with w. Hence the vowel

of the first syllable is liable to drop when the resulting combination of

consonants is easy to pronounce initially; as in Mn. W. pladur ' scythe', for

Ml. W.paladur, CM. 95 (paladnrwyr W.M. 425, 426); Mn. W. gwrando 'to listen',

for Ml. W. gwarandaw, E.M. 16, c.M. 29;

Mn. W. Clynnog for Ml. W. Kelynnawc, IL.A. 124.

Some shortened forms are found, though rarely, in Ml. prose and verse :

gwrandaw, C.M. 27 ; kweirywyt for kywewywyt 'was equipped', E p. 1276 (the y

was written, and then deleted as the metre requires);

pinywn a.p. 1225 from E. opinion ; grennyS do. iog5 for garennyS.

For dywedud 'to say' we geneially have dwedud in Early Mn. poetry (written

doedyd in the 16th cent.); so twysog,^.V. § 32,B.cw.7i, for tywysog '

prince'; cledion c.c. 334, 390, pi. of caled ' hard'; donnaw for calonnau '

hearts', in Tyrd, Ysbryd Gidn, i 'n clonnau ni, E.V.

ii. In words of four or more syllables, when pronounced deliberately, the

first syllable has a secondary accent, as ben\di\ge\dig ' blessed ', pi.

len\dz\ge\ilig\wn. This also applies to tiisyllables with the accent on the

ultima, as cyj \taw\n/iad ''justification '. The least stressed syllable is

the second ; and this is often elided, in which case the secondary accent

disappears ; as in Mn. W.gorcJifygu for ^brcJiyfygii IL.A. 15, and in Mn. W.

verse tragwyddol for tra\gy\wy\ddol ' eternal', partoi for pa ra\t6i ' to

prepare', llytJirennau for llytJiyrenwiu ' letters ', perthndsau ' relations

' for perthyndsau, etc.

Gzoaeddwn, feirdd, yn drag'wyddol;

Gwae id nad gwiw yn i 61.—Gu.O., A 14967/120.

' Bards, let us cry for ever; woe to us that it is useless [to live] after

him.' See o. 160, 253. •

Tn ddgfal beunydd i bart6i.—"Wms. 259.

' Assiduously every day to prepare.'

iii. When a vowel is elided, as in i, ii, or v, the same vowel disappears in

the derivatives of the word; thus pfadwwyr ' mowers '; hvysoges B.CW. 11 '

princess', from twysog, for fywysog ;

tragwyddolileb ' eternity ', yMlarl6i' to prepare one's self, 'wyllys-gar c

willing' (ewyllys, 'wyllys ' will').

'§ 44 ACCENTUATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1585)

(tudalen 55)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

55

Wedi 'mrawd yma'r ydwyf;

Ato, Dduw, ymbartdi 'dd wyJ.—L.Mor. (m. I.F.).

' After my brother I tarry here; to him, Oh God, I am preparing [to go].'

(The metre proves the elision, but not its position.)

In tragwyddoldeb the lost syllable is the second, so that" there is no

departure from the general principle laid down in ii; but in pladur-wyr the

first is lost because the word is foimed fiom the reduced pladur. If

paladurwyr had been reduced dhectly it would have given *paldurwyr ;

similarly twysoges, etc.

iv. Occasionally in Mn. W. haplology takes place, that is, a consonant, if

lepeated in the following syllable, is lost with the unaccented vowel; as

eriedigaeth for erildedigaetft ' persecution', crecl'imol for credaduniol, §

133 (8), ' believing'. (Cf. Eng.

singly for single-ly, 'Bister for Bicester, Lat. stipeiidium for

stipife'n-diufii, etc.)

v. An unaccented initial vowel sometimes disappears, as in Late Ml. W. pinywn

E.P. 1235 'opinion', borrowed from Eng.;

'wyllys for ewyllys in verse ; and in Late Mn. "W. machlud ' to set' (of

the sun) for Ml. and Early Mn. W. ym-achludd, D.G. l2i, § 111 vii (3). As a

rule, however, this elision only takes place

after a vowel:

Tebig yw 'r galennig Idn

I 'dafedd o wlad I fan.—I.D., TB. 142. ' The fair new year's gift is like

threads from the land of [Prester] John.' Another reading is I edufedd gwlad

Ifan, I.D. 22.

Ac efgydft'i ogyfoed

Yw gwr y wraig oreu 'rioed.—L.G.C. 318. ' And he with his mate is the husband

of the best wife [that] ever [was].'

In the dialects it is very common : moral' attend (to)' for ymwol, molchi for

ymolchi 'to wash', deryn for aderyn 'bird', menyn for ymenyn ' butter',

mennyS for ymennyS ' brain ', etc.

vi. In a few disyllables the vowel of the final unaccented syllable is

sometimes elided ; thus o/lid ' but' appears generally as ond in Mn. W. Other

examples met with in Mn. (rarely in Late Ml.) verse are mynd for mfwed ' to

go', tyrd for tyred ' come ! ' gweld for gweled ' to see ', llond for llonazd

' full (capacity) ', cans for cdnys ' because ', namn for ndmyn ' but', all

except the last two in common use in the dialects. Similarly er ys becomes

ers, § 214 vii.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1586)

(tudalen 56)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

56

PHONOLOGY

§45

Ancr wyffi'n cyweirio i frdd, Ond aros mqnd i orwedd.—D.G. 295.

' I am an anchorite making ready his grave, only waiting to go to

rest.'

Cans ar ddzwedd pob gweddi, Cofcywir, yr he-nwir hi.—D.G. 235.

' For at the end of every prayer, unforgotten she is named.'

MaSeu, kanys ti yw'r meSic.—sr. 1298 (7 syll.).

' Forgive, for Thou art the Healer,' The length of the line shows that kwiya

is to be read leans. It occurs written cans in 'W.M. 487.

Ni edrychodd Duw 'r achwyn;

Ni mynnodd aur, namn i ddwyn.—G.GL, M 148/256.

' God did not regard the lamentation ; He desired not [to have] gold, but to

take him away.' See also I G. 380.

See examples of tyrd, dyrd in § 193 viii (2).

vii. The vowel of a proclitic is often elided

(1) After a final vowel, y is elided in the article^/-, § 114 ; the pronouns

yn' our ', ych' your' (now written ein, ezch), § 160 ii (i);

the oblique relative y ox yr, § 83 ii (i), § 162 ii (a) ; the preposition yn,

§ 210 iv.

(2) Before an initial vowel, g is elided in fy ' my', cly 'thy', § 160 i (i).

(3) The relative a tends to disappear even between consonants, § 162 i.

(4) The vowel o?pa or py ' what ? ' sometimes disappears even before a

consonant, as in pie ' where ? ' § 163 ii (2).

(5) After pa, ryw tends to become tf and r, § 163 ii (6).

§ 45. i. (i) Compound nouns and adjectives are accented regularly; thus

gn't/i-i/an 'vineyard', cadew-fardd 'chaired bard', gwag-lalo or lldw-wag '

empty-handed '.

G-wawd-lais niwyalch ar gded-lwyn,

Ac eos ar lws Iwyn.—D.G. 503.

' The musical voice of a thiush in a grove, and a nightingale in many a

bush.'

Yn i dydd ni adai wan

Acw 'TO llaw-wag, Gwenlltan.—L.G.C. 232. ' In her day she, GwcnDian, left not

the weak empty-handed there.'

(a) Even a compound of an adjective and a proper name may be so accented ; as

v45

ACCENTUATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1587)

(tudalen 57)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

57

' Ddqrau am urddedig-Rys <-Yw 'r mSr hallt, os gwir wiarw £hys.—G.GL, M

146/171.

' The salt sea is tears for noble Rhys, if it is true that Ehys is dead,'

See TTchel-Grist, D.G. 259. The name Bendigeid-fran. 'Bian the Blessed', was

so accented, and the/was lost, § 110 lii (3), giving Bendigeidrun (coirupted

into Benegrzdran, in Emerson's English Tiaits, xi).

.ScWo^wydrBendigeidran.—T.A., A 14976/166 ; c. ii 83.

' The glass eaves of Bendigeidi\m.'

(3) When the first element lias one of the mutable sounds ai, au, w, t{ it is

mutated in the compound, becoming ei, eu, y, y respectively, because it is no

longer ultimate when the compound is treated as a single word; thus gweith-dy

'workshop' [gwaith 'work'), heul-drs 'heat of the sun' (haul 'sun'),

dryg-waith 'evil deed' (drwg 'evil'), nielyn-wallt ' yellow hair' (melifn '

yellow'). In old compounds aw also is mutated, as in Udfrwid, § 110 iii (i).

yr A compound accented as above may be called a strict. compound. \

ii. (i) But the two elements of a compound may be separately accented; thus

wel grefydd ' false religion ', gdu hr6jfwyil ' false prophet', fien, wr '

old man ' (sometimes accented regularly, henwr, B.cw. 64).

(2) The diffeience between a secondary accent and a separate accent should be

noted. A secondary accent is always subordinate to the principal accent; but

when the fnht element of a compound has a separate accent it is independent

of the accent of the second element and may even be stionger if the emphasis

requires it. Again, the fust element when separately accented has the

unmutated ai, au, w, or Y in its final syllable ; thus in cyd-nabyddiaeth '

acquaintance ' there may be a secondary accent on cyd (short y), but in mfd

gyn'&ll-wd there is an independent accent on cyd (long y). In fact, when

there is a separate accent, the fust element is treated as an independent

word for all purposes of pronunciation (accentuation, vowel quantity, and

vowel mutation).

@s- A compound accented as above may be called a loose compound.

(3) Sometimes the elements of a loose compound are now hyphened, thus

coel-grefydd; but as any positive adjective put before a noun forma with it a

loose compound, in the vast majority of such compounds the elements are

written as separate words. See § 156 iii.

iii. An adjective or noun compounded with a verb or verbal

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1588)

(tudalen 58)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

58

PHONOLOGY

noun forms a loose compound, as cynjfon Idwni ' to wag the tail', prysur

redant ' they swiftly run'.

Fel y niwi o afael nant T dison ymadawsant.—R.G.D. 149.

' Like the mist from the grasp of the valley liavo they silently passed

away.'

iv. (i) Prefixes form strict compounds with nouns, adjectives, and verbs ; as

athrlst ' very sad' (trist' sad'), dm-gylch ' circumference ', cjn-nal' to

hold', etc., etc.

(2) But compounds with the prefixes an-, di-, cyd-, go-, gor-, gwrth-, rliy-,

tra- may be either strict or loose; as dn-awdd or an hdwdd ' difficult', §

148 i (6); dn-aml/ynys G. 103, an ami, § 164 i (i) ; di-wair, di wdir '

chaste '; rJiy-wyr ' high time' and rKy hwyr ' too late'; trd-mawr Gr.O. 51,

tia mdwr ' very great' ;

trd-doeth do. 53, tra doetk ' very wise'.

Di-dad, arnddifad ydwyf, A di frawd wedi i farw wy],—L.Mor. (m. I.F.).

' Fatherless, destitute, am I, and without a brother after his death.'

Y mae'r ddwyais mor ddiwair.—D.G. 148. ' The bosom is so chaste.'

Fwyn a di wair—f'enaid yw.—D.G. 321. ' Gentle and chaste—she is my soul.' Cf.

D.G. 306.

Tra da im y try deu-air.—I.F., o 18/11. 'Very good for me will two wolds tuin

out.'

In late Mn. W. new compounds are freely formed with these elements separately

accented; thug tra, go and rJiy are placed before any adjectives, and treated

as separate words; § 220 viii (i).

When botli elements are accented, the second has generally the stronger accent,

unless the prefix is emphatic; in gor-uwch ' above', gor-zs ' below ', tlie

first element lias lost its accent, though these are also found as strict

compounds, thus guruwch, O.G., o. 257, Gr.O. 34.

§ 46. i. Expressions consisting of two words in syntactical relation, such as

a noun and a qualifying adjective or a noun and a dependent genitive, are in

some cases accented as single words, ffs- These may be called improper

compounds. Mutable vowels are mutated (// >y, etc.) aa in single words.

They differ from proper compounds in two respects: (i) the initial of the

second element is not softened except where the ordinary rules

ACCENTUATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1589)

(tudalen 59)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

59

of mutation require it; (2) the words are arranged in the usual syntactic

order, the subordinate word coming last, except in the case of numerals, ii

(5) below.

Cf. in Latin tlie improper compounds pater-familias, juris-dictio, in which

the first element is an intact woi d, by the side of the proper compounds

patri-cida juri-dicus in which the first element contains the stem only.

ii. Improper compounds accented on the penult con&isfc of—

(1) Some nouns qualified by da, as gwr-da ' goodman ', gwreig-dda ' goodwife',

hin-dda ' fair weather', geir-da ' good report'. Names of relatives with

maeth, as tdd-maeth' tostel father ', mdmaeth (for mdm-faeth, § 110 iii (i))

' foster mother', mdb-maeth, brdwd-maeth, chwder-faeth. A few other

combinations, such as heul-wen ' bright sun'a {haul fern., § 142 iii),

coel-certh 'bonfire' (lit. 'certain sign'). See also (3) below.

A bryno tir d braint da Tn i drddl d'n Wr-da.—L.G.C. 249.

' He who buys land with good title in his neighbourhood will become a

goodman.'

(2) Nouns with dependent genitives: tref-tad 'heritage', dydd-brawd or

dydd-bam (also difdd brdwd, difdd barn) 'judgement day', pen-tref' village ',

pen-cerdd ' chief of song', yen-tan ' hob'. See ako (3) and (4) below.

(3) Nouns with adjectives or genitives forming names of places;

as Tre-for or Tre-fawr, Bryn-gwyn, Mynydd-mawr, Aber-maw, Mm-jfordd, Pen-fir,

Pen-mon, Pen-won Mdwr.10

Even when the article comes before the genitive, the whole name is sometimes

thus treated, the accent falling upon the article; as Pen-y-berth near

Pwllheli, Tal-y-bryn in Llaunefydd, Clust-y-blaiS near Cenig y Drudion, Mod

y-ci (pron. Mm[\lyc\i), a hill near Bangor, Llan-e-cil near y Bala,

Pen-e-goes near Machynlleth, Pen-e-berth near Aberystwyth (o for y, § 16 iv

(2)). Cf. (7) below. Mi afi ganu i'm oes

I bendig o Ben-6-goes.—L.G.C. 429. ' I will go to sing while I live to a

chieftain of Penegoes.'

(4) The word duw (or di[w) followed by the name of the day in the genitive ;

as Duw-sul as well as Ddw Sul or Dydd Sul ' Sunday'; so Duw-llun ' Monday ',

Duw-mawrth ' Tuesday', and -Dif-wu for Duw law ' Thursday '. Similarly

d(i{w)-gwyl' the day of the feast (of)'.

* It is often supposed that healuen ia a proper compound of hawl and gwSn,

meaning the ' smile of the gun'; but erroneously, for heulwen is the ' sun '

itself, not ' sunshine'.

b The common spelling Penmaenmawr appears to be due to popular etymology. Camden, 4th ed., 1594,

p. 18, has Pen-mon maw, and the word is now pronounced P^n-mon-mduir.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1590)

(tudalen 60)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

60

PHONOLOGY

JSchrys-hamt, och, wir Tesu ! Ddyfod i Idl Ddif-iau dw.—T.A., a. 235.

' A dreadful plague, Oh true Jesus ! that black Thursday should have vi-sited

Yale.' See § 214 vii, ex. 2.

Both accentuations are exemplified in—

Bum i'r gog swyddog Dduw Sul;

Wy ddi-swydd, a hyn Dduw-sul.—T.A., A 149'76/108.

'I was an officer of the cuckoo on Sunday ; I am without office, and this on

Sunday.' (Gwas y gog ' the cuckoo's servant' is the hedge-sparrow.) »

(5) A numeral and its noun, as deu-lwys ' 2 Ibs.', dwy-bunt ' £2 ', can-punt

' £100 ', etc. Gf. E. twopence, etc. Tliough the order is the same liere as

in proper compounds, and tlie mutation is no criterion, it is certain that

most of these are improper compounds. In the case of un, proper and improper

compounds can be distinguished : un-ben 'monarch' is a proper compound, the

second element having the soft initial, but iin-peth is precisely the

combination un peth 'one thing' under a single accent.

(6) The demonstrative adjective after nouns of time. See § 164 iii. (?) Very

rarely the article with its noun, as ill IQ-fenechtyd for

y Fenechtyd 'the monastery', in which tlie aiticle, taken as part of

the word, acquired a secondary accent.

iii. Improper compounds accented on the ultima consist of—

(1) A few combinations of two monosyllabic nouns, of which the second is a

dependent genitive and the first has lost its accent; as pen-rhdith'

autocrat', pen-Had ' summum bonnm ', pry-nhdwn for pryt nawn.

^ Tr eog, r/iywwg ben-rhaith,

At Wen dos eto •dn-waith.—D.Q. 148. ' Thou salmon, gentle master, go to Gwen

once more.'

A 'm cerydd mawr i 'm cdrwd, Ac na'th yawn yn lldwn ben-Had.—D.G. 513.

'And my great punishment for my love, and that I might not have thee as my

whole delight.'

(2) A number of place-names of similar formation, as Pen-tyrch.

NoTE.—(i) From this and the preceding section it is seen that accentuation

-does not always accord with the formation of words. A loose compound is

etymologically a compound, but its elements are accented as separate words.

An improper compound is etymologically a combination of separate words

accented as one word. The accentuation of improper compounds is to be

accounted for thus : in 0. W. we may assume tliat gwr da, Aber Maw, Pen y

berth were orioinally accented as they would be if they were formed now, with

the main

§47

ACCENTUATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1591) (tudalen 61)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

61

stress in each case on the last word. When each combination came to be

regarded as a unit, the main stress became the only accent; thus, *gwr-dS,,

*Aher-mdw, * Pen-y-berth. This wns at that time the accentuation of ordinary

words, such as *pechadur, § 40 iii. When the accent shifted, and *pechadur

became pechddur, *gwr-dd became gwr-da, *Aber-mdw became AVer-maw and

*Pen-y-berth became Pen-y-berth. In most cases of a combination like the

last, each noun retained its individuality, and the original accentuation

remained; hence Pen-y-berth, which is a common place-name, is usually so

accented, and the accentuation Pen-y-berth is exceptional. In such a phrase

as pryt ndwn ' time of noon ', each noun retained its meaning to the Ml. W.

period; then, when the combination came to be regarded as a unit, the first

element became unstressed, resulting in pryt-ndwn, whence pry-nhdwn, § 111 v

(5).

(a) Improper compounds having thus become units could be treated as units for

all purposes ; thus some of them have derivatives, such as gzor-da-aeth,

'nobility', tref-tdd-aeth 'heritage', di-dref-tdd-u S.G. 306 ' to

disinherit', prynhdwn-ol' evening ' adj.

(3) On the other hand, in some proper compounds each element was doubtless

felt to preserve its significance ; and the persistence of this feeling into

the Ml. period resulted in loose compounds.

§ 47. i. In compound prepositions the elements may be accented separately,

a.s/6ddi dr. But the second element has usually the stronger accent; and in

some cases the first element becomes unaccented, as in Ml. W. y gdnn, which

became gaw ' by' in Late Ml. and Mn. W. by the loss of the unaccented

syllable.

On the analogy of y gdnn, y wrth,. etc., derivative and other old

prepositional and adverbial formations retained the 0. W. accentuation, as

oddn, yrwng, yrhdwg.

The separate accent often persists in Mn. W., as in oddi wrth (Ml. W. y

wrth), and in adverbial phrases like oddi yno (in the dialects odd yno as in

Ml. W.). In the latter the first element may become predominant, thus odd yno

' from there' in the spoken language (often contracted to oSno and even ono).

ii. In prepositional and adverbial expressions formed of a preposition and a

noun (whether written separately or not), the last element only is accented;

thus iwch-ben ' above', dra-c/iefit ' again', ger-bron ' before ', uwch-ldw '

above ', ymlaen ' forward', ynghycl' together', i gyd, ' together', erwed '

ever'.

These expressions thus form improper compounds accented on the ultima. The

adverb achlan {achldn) ' wholly' is similarly accented.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1592) (tudalen 62)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

62

PHONOLOGY

§ 47

Hears fat mohwn

I chl6d yng Ngwynedd achlan.—D.G. 235. ' I have sown her praises like a paean

through the whole of Gwynedd.'

iii. Many adverbial expressions of three syllables, consisting of a

monosyllabic noun repeated after a preposition, form improper compounds

accented on the penult; as ol-yn-ol 'track in track', i. e. 'in succession

',"• ben-dfd-phen ' head over head', laio-fn-llalo 'hand in hand', etc.

The first noun may have a secondary or separate accent, as With drd-phlith '

helter-skelter'. The first noun being in an adverbial case has a soft

initial.

A dau frawd ieucif ar 61 Eli enwog ol-yn-ol.—G.GL, c. i 201.

'And two younger brothers in succession after the famous, Eli.' L '^/ Oes hwy

no tlvri, Sion, y'th row,

Law-yn-llaw d'th lawen-lloer.—T.A., A 14866/745.

' For a life longer than three, Si6n, mayst thou be spared, hand in hand with

thy bright moon.' See also E.P. 240.

Ael-yn-ael a'i elynwn.—D.N., c. i 160. ' Brow to brow with his enemies.'

Dal-yn-nal rliwng dwy Idnnerch.—D.N., M 136/147. ' Face to face between two

glades'; ynndl for ^n-nhal, § 48 ii.

Daw o deidmu dad-i-dad,13 Gollwyn hen,—nid gwell un had.—'W.TL.

' He comes from forebears, father to father, like an ancient hazel-grove

—there is no better seed.' f

Arglwyddi lin 6-lin ynt.0—L.G.O. 460. ' They are lords from line to line.'

See icers dragwers IL.A. 164 ' reciprocally', gylch ogylcJi do. 166 'round

about', ddwrn trd-dwrn, law drd-llaw, L.G.C. 18. la many cases the first noun

also is preceded by a preposition, as

Marchog o 1m 6-lin oedd.—L.Mor., I.MSS. 292. ' He was a knight from line to

line.'

gee o Iwyn z-lwyn D.G. 141, o law Uaw do. 145. Of. Late Mn. W. z-gam 6-gam '

zig-zag '.

" Tlie last ol of olynol was mistaken about the middle of the last

century for the adjectival termination -ol (= -awl), and from the supposed

stem olyn an abstract noun olymaeth was formed to render ' succession' in '

apostolical succession '!

b In all the above examples the cynghanedd is either Ta or Os, which implies

the accentuation indicated. See ZfCP. iv. 134, 137.

" The cynghanedd is 84, which implies the accentuation marked. '_

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1593) (tudalen 63)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

63

ACCENTUATION

The ordinary accentuation is also met with in the bards : ^

0 rWyn i 1-^yn, ail 6nid.—D.(x. 84. ' From bush to bush, [maiden] second to Enid.'

iv. When pa or py is followed by a preposition governing- it, the latter only

is accented: pa-ham (for pa am, § 113 i (a)) (what for ? why ?' often

contracted into pam by the loss of the unaccented syllable, § 44 vii. So were

doubtless accented the Ml. W. paJidr A.L. i 108, 134, pa, Mr do. 118 (for pa

ar) ' what on ? ' pa rdc B.B. 50, pyrdc B'.M. 136 ' what for ? '

§ 48. i. When the syllable bearing the principal accent begins with a vowel,

a nasal, or r, it is aspirated under certain conditions, § 112 i (4); thus

ce\nhed\loedd ' nations', from cenedl;

fio\nhe\ddig (vonheSic E.P. 1331) from Sonedd 'gentry', § 104 iv (i);

cy\nhalwyd, from cynnal 'to support' from cyti+da^ (d normally becomes n, not

nh, § 106 ii); di\fidng\ol from di-anc 'to escape'; a phlannhedeu E.P. 1303

'and planets', usually \ planedau; Jcenhadeu w.x. ^84, oftener in Ml. W.

keanadeu do. 42

'messengers'.

A'i aur a'ifedd y gwyr fo, ronh^ddig,'1/y nyliuddo.— L.G.C. 188.

' 'With his gold and mead doth he use, as a gentleman, to comfort me.'

ii. On the other band, an h required by the derivation is regularly dropped

after the accent; as Cannes

' warm', for e^n-nhes from cym+tes (t gives nh, § 106 iii (i)) ; Sr^niw

'king', for brw\nhm from hre\e'n\nftin from *breewtin,, Cornish Srenfyn.;

tdn\nau ' strings', for tdn\nheu from 0. W. tantou M.o.; tang ' wide ', for

eh-ang from *eks-ang-; dwawdd IL.A. 109 for dn-hawdd ' difficult'; drawl '

bright', for ar-haul, which appears as arheui in B.P. 1168. The h is,

however, retained between vowels in a few words, as thud ' foolish', dthau

and Ataw ' right (hand), south' ; and in nrh, nhr,13 nghr, and Irh, as

dnrhaith ' spoil', anhrefn ' disorder', anghred ' infidelity', olrhain ' to

trace'.

The h is also dropped after a secondary accent, as in

^ L. G. C.'s editors print voneddig in spite of the answering h. in nyJiuddo.

1 nrh and nhr have the same Bound but differ in origin : nrh =-- n + rh; nhr

is from B + tr. They are often confused in writing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1594) (tudalen 64)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

64

PHONOLOGY

§ 48

§§ 49, 50

ACCENTUATION

65

brenimdethav, ' kingdoms'. So we have cenedldethau ' generations',

tbiteddigaidd 'gentlemanly' (vonebigeiS B.G. 1129).

in. Note therefore the shifting of the h in. such a word as dihdreb

'proverb', Ml. W. di/iaereh K.P. 1336, pi. dwrhebion, Ml. W. diaerhebyon B.B.

974, 975, 1083. The word has etymo-logically two h's: di-haer-heb, but only

that is preserved which

precedes the principal accent.

iv. Th*e above rules may be briefly stated thus: an intrusive h sometimes

appears before the accent, and an organic h regularly disappears after the

accent. It is obvious that the' rule cannot be older than the present system

of accentuation; it is indeed the direct result of that system, and is

probably not much later in origin. The first change was the weakening and

subsequent loss of h after the accent, giving such pairs as brenin,

brenhinoedd; angen, anghenus (< *nken-, Iv. ecen)', cymar, cymharu (•<

Lat. compar-): here h. vanishes in tlie first word of each pair. Later, on

the analogy of these, other pairs were formed, such as bonedd, bonhcddig ;

cenedl, cenhedloedd; where an intrusive h appears in the second word of each

pair.

In 0. W., when the accent fell on the ultima, it was easy to say bre\en\nhzn;

but when the accent settled on the penult, it required an effort to sound the

aspirate after the breath had been expended on the stressed syllable. Hence

we find, at the very beginning of the Ml. period, breenhineS and breenin L.L.

120. But the traditional spelling, with h, persisted, and is general in B.B.,

as minheu 12 ;

synJi.uir ( s synnhwyr) 17 ; aghen agheu 23 ; breenhin 62 ; though we also

find a few exceptions, as kayeU 35. In B.M. it still survives in many words,

as brenfin 2; agheu, 5 (but angev, ib.); mwyhaf n ;

minheu 12 ; but more usually wwyaf 13 ; minneu 3 ; gennyf 8 ; synn-wyr 13 ;

amarch 36; llinat (for Urn-had) 'linseed' 121. In the B.P. we find dnawS

1227, 1264, 1270, 1299 ; dneirdd, dnoew 1226 ; diagyr (for dt-Jiagr) 1289;

lldwir (for llaw-hir 'long-handed') 1207, 1226;

~ldwl<•ir 1214, witli h inserted above the line—an etymological correction

;

dwrhonn 1271, with h deleted by the underdot—a phonetic correction.

Intrusive h makes its first appearance later, and is rarer in Ml. W. than

lost h. In A.L., MS. A., we find boneSyc ii 6, 14, but in this MS. ft may be

for nh; in later MSS. bonheSyc i 176-8, MS. a. ; bonheSic in Ml. W.

generally. In other cases it is less usual; thus Icennadeu is the form in

B.M., though the older W.M. has sometimes kenhadeu 184, 249 ; kenedloeS

B.B.B. 239, IL.A. 169, so generally.

The orthography of the 1620 Bible generally observes the phonetic rule; thus

brenin, brenhinoedd Ps. ii 6, 2 ; cenedl, cenhedloedd do. xxxiii 12, ii r ;

angeu, anghefol do. vi 5, vii 13; aros, arhosodd JOB. x 12, 13; bonheddig,

boneddigion Es. ii 9, i Cor. i 26; ammarch, ammherchi Act. v 41, Rhuf. 124;

etc. There are some irregularities and inconsistencies; e.g. diharebion

Diar., title, i i, and anghall Diar. i 4 beside the phonetic angall do. viii

5. The Bible-spelling wasv

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1595) (tudalen 65)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

65

generally followed, and the use of h medially was fairly settled OB phonetic lines, when Pughe introduced confusion by

discarding it wherever his mad etymology failed to account for it. His

wildest innovations, such as glandu, pardu for glanhdu, parhdu, were rejected

by universal consent; but his principle was adopted by the " new school

" including T. Charles, Tegid and G. Mechain, who disregard the accent,

and insert or omit h in all forms of the same vocable according to their idea

of its etymology." Silvan Evans (Llythyraeth, 68), writes as if the

cogency of this principle were self-evident, and imagines that to point out

the old school's spelling of cyngor without, and cynghorion with, an h, is to

demonstrate its absurdity. In his dictionary he writes brenines, boneddig,

etc., misquoting all modern examples to suit his spelling; under ammeuthun

(his misspelling of amheuthun) he suppresses h in every quotation.

In spite of the determined efforts of the " new school" in the

thirties, present-day editions of the Bible follow the 1620 edn. with the

exception of a few insertions of etymological h, as in brenin, ammarch, which

appear as brenhin, ammharch.

short.

Quantity. In Mn. W. all vowels in unaccented syllables are

Unaccented syllables here include those bearing a secondary accent, in which

the vowel is also short, as in cmedldethau, though before ft vowel it may be

long in deliberate pronunciation, as in dealltwrweth. ,

In Late Ml. W. the same rule probably held good, but not necessarily earlier.

In 0. W. it was clearly possible to distinguish in the unaccented penult the

quantities preserved later when the syllable became accented, § 56 iv.

§ 60. Vowels in accented syllables in Mn. W. are either (i) long, as the a in

edn 'song'; (a) medium as the a in canu; or (3) short, as the a in cann '

white', cannw ' to whiten'.

In monosyllables a long vowel (except i or u) is generally circumflexed

before n, r or 1, § 51 iv, and in any other case where it is desired to mark

the quantity. Short vowels are marked by \ which is sometimes used instead of

doubling the consonant, as in D.D. s.v. can == gan ' with', and before I

which

"• G. Mechain (iii. 224) writing to Tegid, assents to brenin, hreninoedd

"though from habit I always read 'brenMnoedd with an aspirate; but the

root does not warrant such reading." His pronunciation was correct; and

it juat happens that the " root" does warrant it; see $ 103 ii (i).

1401 V

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1596)

(tudalen 66)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

66

PHONOLOGY

§ Sl

cannot be doubled in writing; ddl B.CW. 91, hel do. 95, calon Hyff. Gynnwys

(1749) pp. 3, ao, 319 bis.

6®-In this grammar the circumflex has been retained in most cases where it

is, or might be, used in ordinary writing. But where the position of the

accent has to be indicated, is used;

where there is no need to point out the accent, and the word is not usually

circumflexed,' is used. As every long vowel must •be accented in Mn. W., it

will be understood that ','' and " in Mn. W. words mean the same thing.

In Brit. and earlier a vowel marked ' is not necessarily accented. As ' is

required to denote a secondary accent it would be confusing to use it to mark

a short accented vowel; hence * is used here for the latter purpose, where

necessary. The accent mark / denotes accent without reference to quantity. A

medium vowel can only be indicated by showing the syllabic division ; thus cd

wi,

NOTE. The medium vowel, or short vowel with open stress, which occurs in the

penult, is not heard in English where a penultimate accented vowel, if not

short as in fathom, is long as in father. Silvan Evans calls the medium vowel

"long", and J.D.R. often circumflexes it. Bat the a of cd\nu is not

long, except in comparison with the a of cdn\nu; beside the a of can it is

short. It is a short vowel slightly prolonged past the point of fullest

stress, so as to complete the syllable, and the following consonant is taken

over to the ultima.

§ 61. i. If a vowel in a monosyllable is simple its quantity is determined by

the final consonant or consonants, the main principle being that it is long

before one consonant, short before two, or before a consonant originally

double ; see § 56 ii.

ii. The vowel is short before two or more consonants, or before p, t, c, m,

ng; as cant ' hundred', torf ' crowd', p6rth ' portal', bardd ' bard', at '

to', lldc ' slack', cam ' crooked', Hong 'ship'. . \

Nearly all monosyllables ending in p, t or c are borrowed; some from Irish,

as brat ' apron', most from E. as hap, top, het, pot, cnoc, which simply

preserve the original quantity. E. tenuis after a long vowel becomes a media,

as W. cl6g < E. cloak, W. grod o. 157 < E. groat, re-borrowed as gr6t;

so the late borrowings c6t, grdt (but in S. W. c6t).

W. at is an analogical formation, § 209 vii (2); ac, new should be ag, nag in

Mn. orthography § 222 i (i), ii (3).

§ 51

QUANTITY

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1597)

(tudalen 67)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

67

Exceptions to the above rule are the following:

(1) In N. W. words ending in s or 11 followed by another consonant have the

vowel long; as trzst 'sad', cosh 'punishment', hallt 'salt' adj., etc.,

except in borrowed words, as cast 'trick'. In S. W., however, all such words

as the above conform to the rule.

(2) The vowel is long when it is a late contraction, § 33 iv; as ant ' they

go ', for a-ant; hdm ' I have been ', for bu-um; bont ' they may be', for

bo-ont; rh6nt ' they give', for rho-ant. In 'ijm ' we are', i/nf ' they are',

the vowel is pronounced long; it is marked long by J.D.E. 94; but E.P., PS.

Ixxv r, rhymes ynt with hynt, and in Ml. "W". it is written ynt

(not *yyn£); hence the lengthening is probably due to false analogy.

Cant' they shall have ' is for ca-ant and has long a; but cant' sang' is for

can-t, and is therefore short. Even gweld, § 44 vi, from gwSl, has the e

shortened by the two consonants; a fortiori, in cant ' sang' where the final

double consonant is older, the a must be short. Silvan Evans (s. v. canu)

adopts the error of some recent writers, and circumflexes the a in cant, even

where it rhymes with chwant, and in quoting Gr.O. 82, where no circumflex is

used. The word never rhymes with ant, gwndnt, etc.

W The vowel is circumflexed when long before two consonants, except where the

length is dialectal.

(3) The mutated form deng of deg 'ten ' preserves the long vowel of the

latter in N.iW.

iii. The vowel is long if it is final, or followed by b, d, g, f, dd, ff, th,

ch, B ; as ty ' house', lie ' place ', mob ' son', fad ' father', gwag '

empty ', dof ' tame ', rfiodd ' gift', doff ' lame', crotJi' womb', cocJi '

red ', glas ' blue '.

Exceptions : (i) Words which are sometimes unaccented, vi below.

(2) Words borrowed from English, as sad ' steady', twb, fflach (tromflash),

loch (from lash). SUd, also written sut, ' kind, sort' from suit (cf.

Chaucer, Cant. Tales 3241) is now short; but in D.G. 448^it is long, rhyming

with hud.

(3) Some interjectional words, such as chwaff, pvff, ach. The interjection

och is now short, but is long in the bards; see Oeh / ffoch D.G. 464. Cyjfis

now sometimes incorrectly shortened.

tsr A long vowel need not be circumflexed before any of the above consonants.

In the case of a contraction, however, the vowel is usually marked; thus

rlwdd ' he gave ' for rhoodd for rhoddodd. In such forms the circumflex is

unconsciously regarded as a sign of contraction, and may be taken to indicate

that the vowel is long independently of the character of the consonant.

The circumflex is also used in ndd ' cry' to distinguish it from nad 'that

not'.

iv. If the vowel be followed by 1, n or r, it may be long or r2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1598)

(tudalen 68)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

68

PHONOLOGY

§ 31

§52

QUANTITY

69

short: tdl' pay', dal' hold', can ' song ', cda ' white '; car ' relative ',

car ' car'.

Each of these consonants may he etymologically single or double.' Dal is from

*dalg- § 110 ii (2), so that the final 1 represents two root consonants. In

0. and Ml. W. final n and r when double in origin were doubled in writing, as

in penn, ' head', Irish cenn, in other cases of course remaining single as in

hen ' old ', Irish sen; thus the principle that the vowel is short before two

consonants, long before one, applied. The final consonant is now written

single even in words like pen, and only doubled when a syllable is added, as

inpennaf, cf.Eng. sin (0. E. sinfi) but sinner (though even medial -nn- is

now sounded -n,- in Eng.).

It is therefore necessary now to distinguish between long and short vowels in

these words by marking the vowels themselves.

gap In a monosyllable, a long vowel followed by 1, n or r is circum-flexed;

thus, tdl' pay', coin, ' song', d6r ' door', del ' may come', hyn ' older'.

But i and u need not be circumflexed, since they are always long before these

consonants, except in prin, and in (= Ml. W. ynn 1 to us'), and a few words

from English as pzn, bzl. The common words dyn, hen, 51 are seldom

circumflexed.

Ml. ~W. -nn is still written in some words, e. g. in onn ' ash' pi. ynn, as

in the names Llwyn Onn, Llwyn Ynn. Doubling the consonant is preferable to

marking the vowel when it is desired to avoid ambiguity, as in cann ' white

', a yrr ' drives'. It is not sounded double now when final; but the

consonant is distinctly longer e. g. in pen than in hen. In Corn., penn

became pedn.

NOTE. The a is long in tdl' forehead, front, end', and was circumflexed down

to the latter part of the i8th cent.; see D.D. a.v., G. 68. The 1 is

etymologically single, as is seen in the Gaulish name Cassi-talos. In the

spoken language the word survives only in place-names, and is sounded short

in such a name as Tal-y-bdnt because this has -become an improper compound

accented on the ultima, § 46 iii, so that its first element has only a

secondary accent, § 49. When the " principal accent falls on it, it is

long, as in Trwyn-y-tal near the Rivals. Tegigil o tal, Edeirnaun, Idl B.B.

74 ' Tegeingi to its end, Edeirnawn, [and] Yale.' The rhyme with Idl shows

the quantity of tdl.

f fun araf, fain, eirian, A'r, t&lfal yr aw mdl mdn.—D.G. 330.

' The calm, slender, bright girl, with the head like finely milled gold.'

v. When the word ends in 11 the quantity varies. In N. W. it is short in all

such words except oil, /toll; in S. W. it is long, except in gall ' can ',

dwR ' manner', mibll' sultry ', cyll' loses ', and possibly some others.

vi. Many prepositions, adverbs and conjunctions, which are long by the above

rules, by being often used as proclitics have become short even when

accented, more especially in N. W.; as r1iag 'against', hell 'without', nid,

nad 'not', dm 'under' (originally one 11), mdl,fdl,fel' like', ag (written

ac) ' and ', wig (written nac) ' nor' ; but ag ' with '.

The long vowel is preserved in some of these in 8. "W. The word nes

'until', § 215 i (2), was circumflexed even by N. W. writers as late as the

i8th cent., see nes Q. 237; it is now sounded nes (already nes in B.CW. 83,

115 beside nes ' nearer' 13, 109, no). In D.G. dan ' under ' has long a: ,

Serchog y cdn dan y d'ail.—D.G.223.

' Lovingly it sings under the leaves.' i

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1599)

(tudalen 69)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

69. i. If the vowel in a monosyllable is the first

element of a diphthong, its quantity depends chiefly upon the form of the

diphthong.

ii. The vowel is long in ae, oe,wy ; thus trded' feet', oen' lamb', 1iwyr '

late', cae ' field ', caem ' we might have ', doe ' yesterday', mwy ' more',

cwyn ' complaint', /iwyiit ' they', bloesg ' blaesus ', rhwysg ' pomp ',

,'maent' they are', troent' they might turn '.

iBut except before -sg, wy is short before two or more consonants or m ; as

twym, twymn,' hot', rivwym 'bound' (also rhwym), owymp ' fall' (now proti.

cw^mp in N. W.), llwybr ' path', rhwystr ' hindrance',' brwydr' battle

',pwynt' point' ; — hwyntis influenced by hwy 'they'.. Similarly maent formed

from, and influenced by mae. The other. cases are examples of contraction:

caem < ca-em, tr6ent < tro-ynt.

iii. The vowel is short in all other falling diphthongs ; as Mi ' fault', iyw

' alive', troi ' to turn ', llaid ' mud', brw ' wound ', duw ' god ', buzoch

' cow ', haul ' sun', aw ' gold ', dewr ' brave ', bazod ' thumb', mawl'

praise ', etc.

Exceptions: (i) Tn N. W. aw, ew are long when final only; as taw I 'be

silent', 'bow 'dirt', llezv 'lion', two 'fat'; otherwise short as above. In

S. W. the diphthongs are short in both cases.

(2) au is long in traul 'wear, expense', paun 'peacock', gwaudd ^

'daughter-in-law', ffav, 'den', gwaun 'meadow', caul 'rennet', pdu '

country'. The form gwaen is a recent misspelling of gwaun. In West Gwynedd the word is pronounced gweun (esa), Ml. W.

gweun, 0. W. guoun.

(3) The vowel is long in du when contracted for a-au, as in pidu ' plagues';

but in cdu for cde-u, § 202 iii, it is short. It is long in &i for a-ai,

and 6i for o-ai when final, as gwndi, troi 3rd eg. impf.; but

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1600)

(tudalen 70)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

70

PHONOLOGY

53, 54

6i for o-ai not final, as in trois for tr6-ais. On account of the long vowel

gwnai, troi, etc. are generally sounded and often written gvmae, troe, etc.;

but in the bards -di rhymes with ai, see wn^i / ehedai o. 242. Both forms are

seen in Ml. W. gwnai W.M. 25, 54, gwnay B.M. 237 (ae=ay, § 29 ii (i)).

(4) The vowel is long in o'l, a'i, da z, etc., § 33 v, of course only when

accented. In Ml. W. o'i, a'i are written oe, ae or oy, ay.

§ 63. When the accent in a polysyllable falls on the ultima, the above rules

apply as if the ultima were a monosyllable ; thus, short, paJiam ' why ? ',

penaig, §41 iii (2), parh&ti, ' to continue ', gwyrdrSi ' to distort';

long, Cymraeg, parh&nt (for parha-ant}, gwyrdroi (for gwyrdro-ai) ' he

distorted', penllad ' summnm bonum'.

In parhau, caniatau, etc., some recent writers circumflex the a, possibly a

practice first intended to indicate the long vowel in the uncontracted form

-ha-u, § 54 iii. When contracted the a is short. In D.D. and Bible (1620) it

is not circumflexed. J.D.R. 144 writes cadarnhuu. But see § 55 ii.

§ 54. In the accented penult—

i. (l) The vowel is short, if followed by two or more consonants, or by p, t,

c, m, ng, 11, s ; as harddwch ' beauty', plentyn ' child ', cannoedd'

hundreds ', Vjjrradi ' shorter ', estron' stranger', epil 'progeny', ateb

'answer', ameu, ' to doubt', angen ''need' Wan ' out', lesu ' Jesus', glandeg

' fair', glanwaith' cleanly ', tamo ' to fire ', tybzaf ' I suppose'. There

is no exception to this rule, though before m the vowel is sometimes wrongly

lengthened in words learnt from books, such as trumor ' foreign', amwy's '

ambiguous'.

Silvan Evans marks many obsolete words, such as amwg, amug with long a, for

which there is no evidence whatever; it merely represents his own misreading

of Ml. W. -m-, which always stands for -mm-.

(2) The consonants above named are each double in origin. In Ml. W. t, c, s

were usually doubled in this position, as atteb, racco or raoko, messur; but

-m- is generally written single, owing to the clumsiness of -mm- and its

frequency ; possibly -p-, which is not very common, followed the analogy of

-m-; 11 and ng being digraphs can hardly be doubled in writing. In early

Bibles m and p are doubled;

and Cr:E. wrote gallu, doubling ; (his / = tt). As however each is

e^rmologically double (except in borrowed words), the double origin

/

'§ 84

QUANTITY

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 1601) (tudalen 71)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

71

is sufficiently indicated by writing the letter; thus ateb is necessarily the

same as atteb; mesur is necessarily messur. So every medial or final m, ng or

11 means mm, ion, or fttt etymologically, and is so pronounced in the

accented penult.

68" But in the case of n and r the consonant is not necessarily double;

hence a distinction must be made between single and double n and r. The a in

cannu ' to whiten ' is short because it is followed by nn, representing

original nd (cf. Lat. candeo) ; the a in canw ' to sing' is medium because it

is followed by a single n (of. Lat. cano). The distinction is made in nearly

all Ml. MSS., and generally in Mn. MSB. and printed books down to Pughe's

time.

(3) The accented syllable is " closed " (stopped, blocked) by the

first of the two consonants, thus glan\deg, pUn\tyn, can\nu. Even i and w

cause the preceding consonant to close the penult; thus glan\waith from gUn '

clean '. Ml. scribes, knowing that the syllable was closed by two consonants,

and not knowing that the second in this case was i or w, sometimes doubled

the first consonant, as in dynnyon W.M. 32, (g)lannweith E.M. 52; but as a

rule, perhaps, it is written single, as in dynyon R.M. 21, (g)lanweith W.M.

72. A consonant originally double cannot be distinguished from one originally

single in this case ;

thus tan-io' to fire ', from t&n ' fire', and glan-w ' to land', from

glawiz ' shore', form a perfect double rhyme. It is therefore unusual to

double the consonant in the modern language in these forms; glannio and

torriad are written glanio and tariad, which adequately represent the sound

(cf. pentreffor penntref, etc.). Thus in ysgrifennwyd ' was written' the

double n. indicates that the w is a vowel; in ysgrifenwyr ' writers', the

single n indicates that the w is consonantal. Hence some words like annuyl

C.M. 70, synnwyr a.M. 116 are now written with one n owin-g to a common, but

by no means general, mispronunciation of wy as wi[; see P.IL. xcvi, where

Llyr / ssynwyr is condemned as a false rhyme.

ii. The vowel is medium if followed by b, d, g, ff; th, oh, 1,

single n, or single r; as g6\laith 'hope', d\deg 'time', se\gur ' idle ',

e\ffaH?i. ' effect', e\thol' to elect ',pe'\c/tod ' sin', ca\nu ' to sing',

b6\re ' morning', ca\lan ' new year's day '.

In this case the accented syllable is " open" (free), that is, it

ends with the vowel, and the consonant is carried on to the next syllable.

See §50, Note; § 27 i.

In a few forms we have a short vowel before 1, as in l8l\o (often mis-read

I6\ld); cal\on ' heart'; c6l\yn ' sting', 0. W. eolginn svv.;

b8l\wst 'colic' < *bolg-; dSl\ir 'is held' for dSl\w §36 i <*dSlj,ir.

In Ml. "W. such forms are written with double 1, § 22 ii.

Double I cannot be from original II, which gives the voiceless Welsh II W).

It occurs only in a new hypocoristic doubling as in lol-lo, or where a

consonant now lost closed the syllable before disappearing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1602) (tudalen 72)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

72

PHONOLOGY

§ S5'

in colon the lost consonant is w; in cSlyn it is i < ^', w drops before o,

and ^ before y § 36 iii, ii;—calon (Corn. colon, Bret. lealon, kaloun) <

*kaluond- : W. colweS B.A. 6 ' heart', coludd ' entrail' : Skr. krodd-h'

breast, interior': Gk. ^oXaoes, 0. Bulg. Kelqd-uku ' maw' with 9^' ('S'/fff''

alternation).—For Early Mn. W. calyn ' to follow' the Ml. eanlyn has been

restored in writing.

A short vowel also occurs in cadwn, tybir, etc. § 36 i.

'• iii. The vowel is long- if followed by a vowel or h ; as e og 'salmon',

cU-hazi, ' right, south', Gwem \ id \ an.

iv. It is short in all falling' diphthong's'; as cSe\ad ' lid', mwy\af

'most', llSi\af ' least', rhwy\dav, 'nets', lliSy\brau 'paths', Jim\log

'sunny', tw\dwr 'thickness', byw\yd 'life^, cndw\dol' carnal'.

But in N. "W. the vowel is medium in aw, ew, iw before a vowel, that is

the w is heterosyHabic; thus ta\wel ' silent', te\wi ' to be silent', lle\wod

' lions', m\wed 'harm'. In S. W., however, these are sounded taw\el, tSw\i,

llSw\od, ntw\ed.

§ 55. i. The above are the quantities of the vowels in the Mn. language. They

were probably the same in Ml. W. where the-vowel is simple. Thus map or mab,

tat, gwac had A long a like their modern equivalents mob, tad, gwag ; for

where the vowel was short and the final consonant voiceless (=Mn.^, t, c),

the latter was doubled, as in bratt K.G. 1117, Mn. W. bratt D.D., or brat (s

brat) ' rag, apron'. In the case of Ml. single -t, both<fche long vowel

and the voiced consonant are attested in the spelling of foreigners ; thus

the place-name which is now Bod Feirig, which in Ml. W. spelling would be

*-Bo< veuruc, appears in Norman spelling in the Extent of Anglesey, dated

1294, as Sode-ueuryk (Seebohm, Trib. Sys.1 App. 6), where bode doubtless

means bod, the Mn. W. sound. Again in the Extent of Denbigh, dated 1335, the

Mn. W. ~RJios appears as Roos (op. cit. 72), showing the vowel to he long before

s then as now. The N. W. long vowel before st is attested in 1396 in the

Kuthin Court Rolls p. 15,1. 10 in the spelling Neeste of the name Nest. The

distinction between medium and short in the penult is everywhere implied in

Ml. spelling; and we are told in K.G. nao that the vowel is long when

followed by another, as the i in Gwenlliant, Mn. W. Gwen-lli-an. Thus the

quantity of a simple vowel was

§ S6

QUANTITY

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1603) (tudalen 73)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

73 a

generally the same In all positions in Ml. and Mn. W., even local usage

agreeing ; except in shortened words § 51 vi.

ii. But in diphthongs many changes must have taken place. As a " vowel

before a vowel " was long then as now, tro-'i must have had a long o, so

that, when first contracted, it was still long ;

it remains long in Montgomeryshire; thus the short o in trot is probably

late. Similarly short Si for e-i, au for a-u, w for o-u. Other diphthongs

also probably differ, and we can infer nothing as to Ml. W. quantity in

diphthongs from the Mn. W. pronunciation./

§ 56. i. The quantity of-a vowel in British determines its quality in Welsh ;

but its quantity in Welsh depends, as we have seen, on the-consonantal

elements •which follow it in the syllable.

ii. A short accented vowel in Brit. or La-tin followed by a single Consonant

was lengthened in Welsh; thus Brit. * tolas gave tal, § 51 iv Note, *r6ta

(cognate with Lat. rota) gave rhod, Lat. sonus gave son, etc. This took place

after the change in the quality of long vowels, • for while original a gives

aw § 71, long a lengthened from a remains A. If also took place after the

reduction of pp, tt, w iatojf, th, ch, for the latter are treated as single

consonants for this purpose; thus Lat. saccus became *sa^os with single ^,

which gives sach (ssa^) in Welsh. Long vowels remained long, as in pilr from

Lat. purus. On the other ha'n^, a vowel originally long was shortened before

two consonants; thus the o of Lat. forma became u, which was shortened in the

Welsh ffUrf. Hence the general rule § 51 i, which probably goes back to Early

Welsh and beyond; for the lengthening of short vowels originated at the time

of the loss of the ending, and is due to compensation for that loss.

iii. There is no reason to suppose that this lengthening took place only in

monosyllables. Thus 0. W. litan ' wide' (: Gaul. litanos in KoyKo-XtTavos,

Smertu-litanus, etc., Ir. lethan) was probably sounded *lly-daiz, while

guinlann was doubtless *gwinl(f)an'ii. In Ml. W. when the ultima became unaccented

this distinction was lost, the a of llydan being shortened, § 49, and the nn

of gwm-llann being simpli-. fied, § 27 ii. The rule forbidding the rhyming of

such a pair was handed down from the older period, and is given in E.G. 1136;

such a rhyme is called trwm ao ysgawn ' heavy [with 2 consonants] and light

[with one]'. But the bard's ear no longer detected any difference in the

unaccented ultima; he is therefore instructed to add a syllable to find out

whether tlie syllable is "heavy" or "light": kalloxna.eu

{U = l-T) is given as an example to show that the on(%) of Jcallon [sic] . is

" heavy ", and amkcm.eu to show that the an of amkan is "

light". The Early Ml. bards avoid trwm ac ysgawn; but in the first poem

in B.B., where the rhyme is -ann, several forms in -an occur, as imuan i (:

gwanaf ' I wound'), darogan ^ (: canaf ' I sing'), which shows that

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1604) (tudalen 74)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

74

PHONOLOGY

57, 5i?

the distinction was beginning to disappear. The Late Ml. poets frankly give

it up; e. g. Ca. bychan / glan / kyvan(n) / dvflan(n) / darogan/ . . .

!calan(n) / kan / Ieuan{n), E.P. 1233-4. Yet in 0. W. the distinction was a

real one, for it is reflected in the ordinary spelling of words; as Uchcm.

ox. 'little' (cf. vychaTO.et W.M. 44, E.M. 31), atac ox. 'birds' (cf. adaven

B.B. 107), scribenm. M.O. 'writing' (cf. yscrivesnau IL.A. 2), corsetca. ox.,

gmnlawa. JUV., ^tc. The dimin. endings -yn, -en appear as, -inn, -din ; the

pi. ending -•wn is always -ion.

iv. In the unaccented penult in 0. W. the distinction between an open and a

closed syllable was preserved; the vowel must have been shorter in the

latter, as it was later when the penult became accented.

v. The diversity in the present quantity of vowels before II and e, and the

fixing of the present quantities- of diphthongs, are due to complicated

actions of analogy, which it would take too much space here to attempt to

trace.

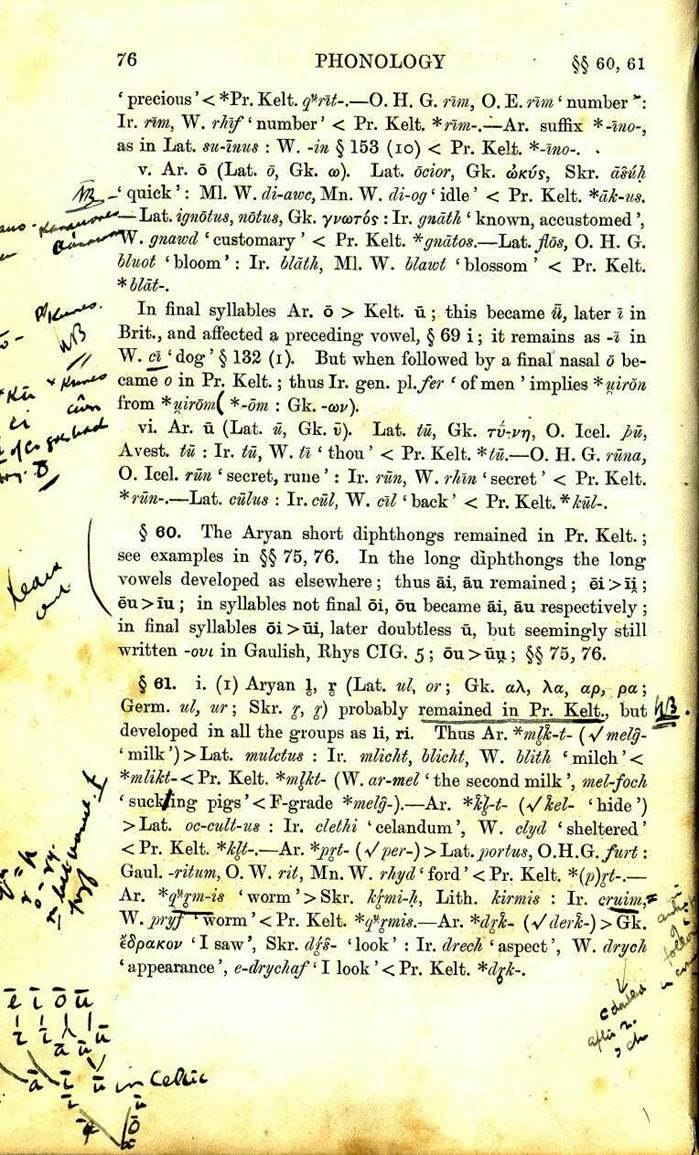

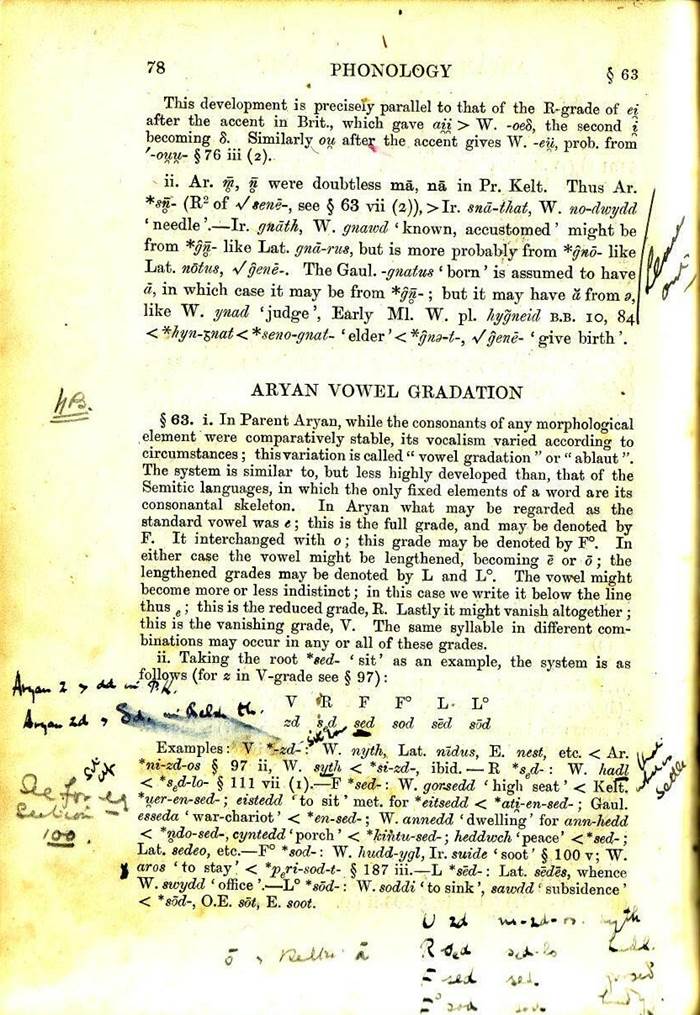

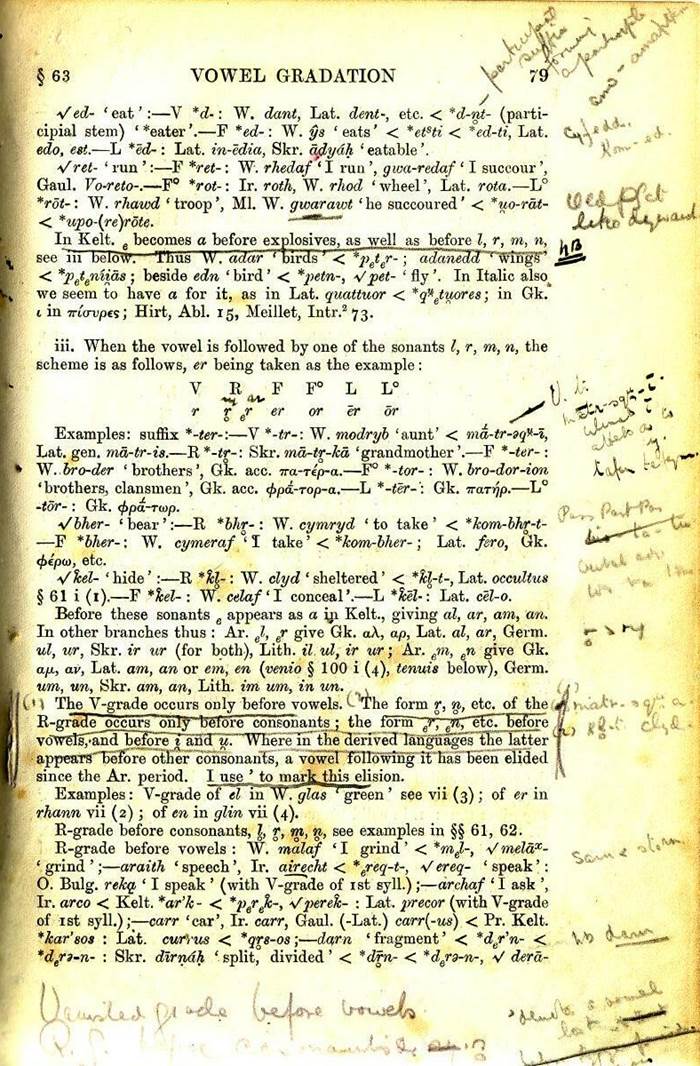

THE ARYAN VOWELS IN KELTIC

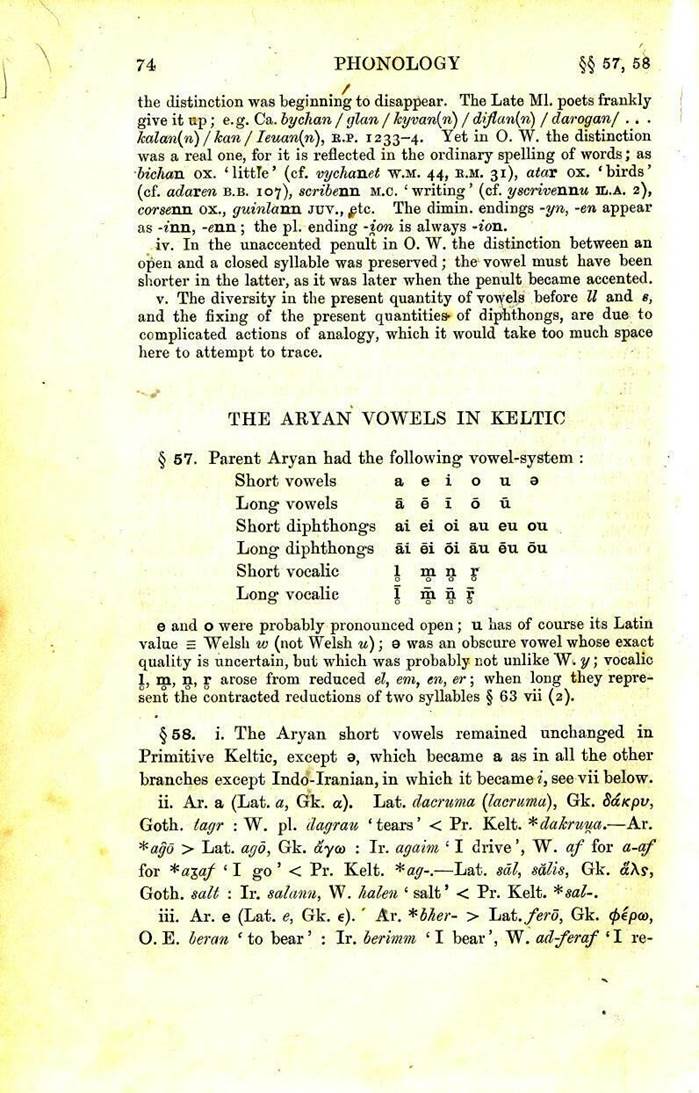

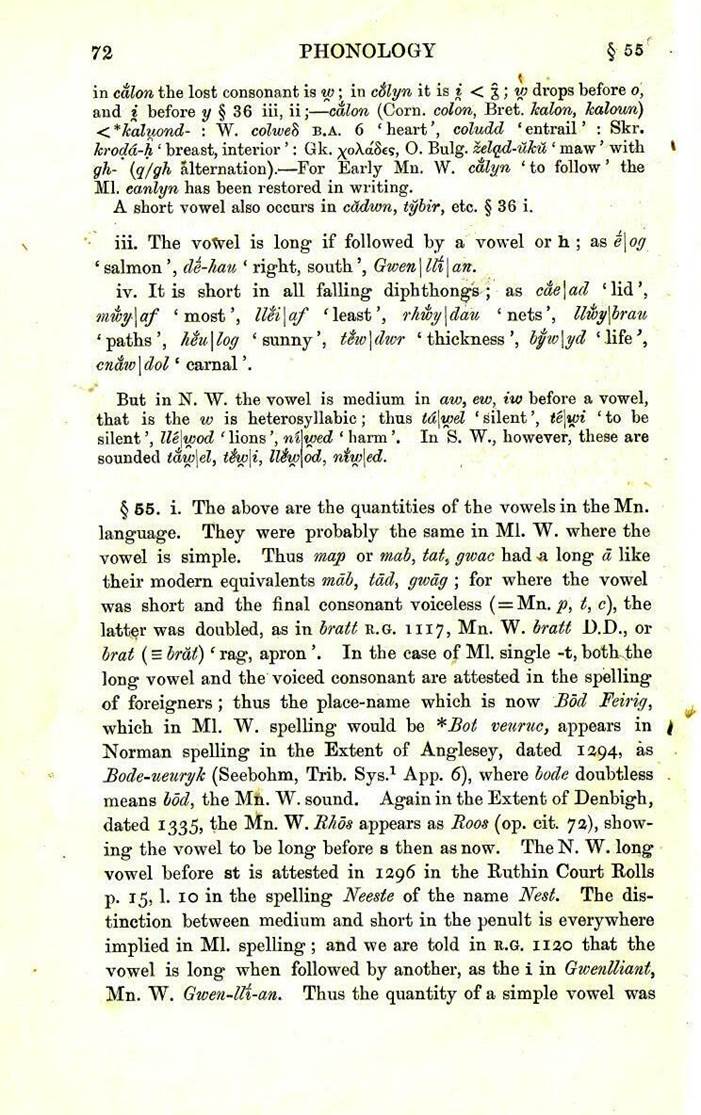

§ 57. Parent Aryan had the following' vowel-system :

Short vowels Long vowels Short diphthongs Long diphthongs Short vocalic Long

vocalic

a e i o u a a e i 6 u ai ei oi au eu ou ai ei oi au eu ou

I m n r I m n r

e and o were probably pronounced open; u has of course its Latin value =

Welsh w (not Welsh u); a was an obscure vowel whose exact quality is

uncertain, but which was probably not unlike W. y ', vocalic 1, m, n, r arose

from reduced el, em, en, er; when long they represent the contracted

reductions of two syllables § 63 vii (2).

§ 68. i. The Aryan short vowels remained unchanged in Primitive Keltic,

except a, which became a as in all the other branches except Indo-Iranian, in

which it became i, see vii below.

ii. Ar. a (Lat. a, Gk. a). Lat. dacruma (lacruma), Gk. SaKpv, Goth. tagr : W.

pi. dagrau 'tears' < Pr. Kelt. *da&ruya.—Ar. *ag6 > Lat. ago, Gk.

aycu : Ir. agaim ' I drive', W. of for a-af for *a!af '1 go' < Pr. Kelt.

*ag:—Lat. sal, salis, Gk. aXy, Goth. salt : Ir. salanw, W. halen ' salt' <

Pr. Kelt. *sal-.

iii. Ar. e (Lat. e, Gk. e). ' Ar. *bher- > liat.fero, Gk. (f>epa>,

0. E. herein, 'to bear' : Ir. berimm 'I bear', W. ad-feraf 'I re-

§ 59

ARYAN VOWELS IN KELTIC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1605) (tudalen 75)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

75

store' < Pr. Kelt. *&('/•-.—Ar. *medhu- > Gk. y.i6v 'wine', 0. H.

G. metu ' mead', 0. Bulg. medw ' honey', Skr. mddhw ' honey': W. medd 'mead',

meddw ' drunk ' < Pr. Kelt. *medu-

*medu-.—Ar. + ekMS > Lat. equv,s, Skr. dsva-h : Ir. ecfi ' horse ', Gaul. Epo- (in Epo-redia, etc.), W. eb-ol' colt' <

Pr. Kelt. *c^-.-> A .

iv. Ar. i (Lat. i, Gk. t). Ar. *md- (Vueid- 'see, know') > u .^A^t)^-Lat.

video ' I see', Gk. Horn. Fi8p.w, Goth. witum ' we know': — Ir. jfisss '

knowledge', W. gwys ' summons' < Pr. Kelt. *wiss-, § 87 ii.—Ar. *uli^-

(Vyeletq"- ' wet') > Lat. liqueo : Ir. fiwcJt ' wet', W. gwlyJ) '

wet' < Pr. Kelt. * yliq»-.

v. Ar. o (Lat. o, Gk. o). Ar. *oito(u) > Lat. octo, Gk. OKTW :

Ir. MM, W. wyth 'eight' < Pr. Kelt. *okt6, §69 iv (a). Ar.

*logk- (Viegh- 'lie') > Gk. Xoy^os 'bed, couch, ambush', 0. |, Bulg.

sa-logu ' consors tori': W. go-lo-i, E. p. 1040, 'to lay, bury' ' <Pr.

Kelt. *log-.—A.T. *tog- (V\s)t1wg- ' cover')> Lat. toga : W. » fo

'roof',§104ii(3).

. vi. Ar. u (Lat. u, Gk. v). Ar. weak stem *'kwi- > Gk. gen. sg. KVVOS,

Goth. bunds, Skr. gen. sg. suHaJt: W. pi. cwn' dogs' < Pr. Kelt.

*ktm-es.—Ar. *sm-f- {^/sreti- 'flow') > Gk. pvTOS ' flowing ', Skr. smtah

' flowing', Lith. sruta ' dung-water ':

Ir. smth ' stream', W. rJiwd ' dung-water ' < Pr. Kelt. *srut-.

vii. Ar. e (see i). Ar. *pater *pater- > Lat. pater, Gk. Trarrjp, Goth.

fadar. Arm. hair, Skr. pitdr- : Ir. athir 'father' < Pr. Kelt. *{p)atw.—Ar.

*s9t- (v^e- 'sow')>Lat. satus ; W. had, ' seed' < Pr. Kelt. s) sat; §

63 vi (i).

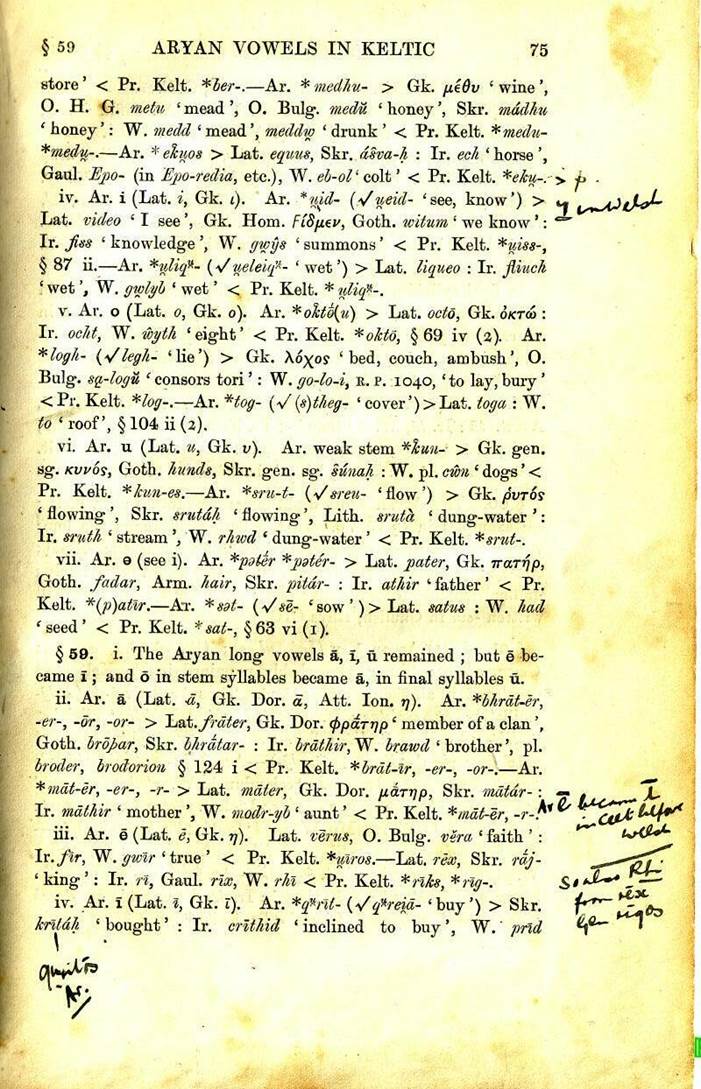

§ 59. i. The Aryan long vowels a, i, u remained ; bat e became i ; and 6 in

stem syllables became a, in final syllables u. ii. Ar. a (Lat. -a, Gk. Dor.

a, Att. Ion. i]). Ar. *bhrdt-er,

*er-, -w, -or- > 'Lat.frdfer, Gk. Dor. <f>paTi]p' member of a clan',

Goth. Sro^ar, Skr. Mmtar- : Ir. brathir,^. brawd 'brother', pi. bioder,

brodorion § 124 i < Pr. Kelt. *bmt-w, -er-, -or-.—Ar.

*mat-er, -er-, -r- > Lat. mater, Gk. Dor. y.a,Tt]p, Skr. mdtdr-: — f 'X

Ir. mdthir ' mother ', W. madr-yb' aunt' < Pr. Kelt. *maf-er, -r-^'1 ^

't^t*<L^<

iii. Ar. e (Lat. e, Gk. i;). Lat. verws, 0. Bulg. vSra ' faith ': '"'

Ir.^fir, W.gwzr 'true' < Pr. Kelt. *mros.—Lat. rex, Skr. mj-' king': Ir.

)i, Gaul. rice, W. r/iz < Pr. Kelt.

*n&, *ng-.

iv. Ar. i (Lat. i, Gk. i). Ar. *q"rU- {V^rew- 'buy') > Skr. krUdJt '

bought' : Ir. wzthid ' inclined to buy', W. pnd

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1606) (tudalen 76)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

76

PHONOLOGY

60, 61

§62

ARYAN VOWELS IN KELTIC

77

' precious' < *Pr. Kelt. c^nt-.—0.

H. G. rw, 0, E. Tzm' number ":

Ir. rim, W. rlwf ' number' < Pr. Kelt. *w%-.—Ar. suffix *-wo-, as in Lat.

su-mus : W. -in, § 153 (10) < Pr. Kelt. *-mo-. •

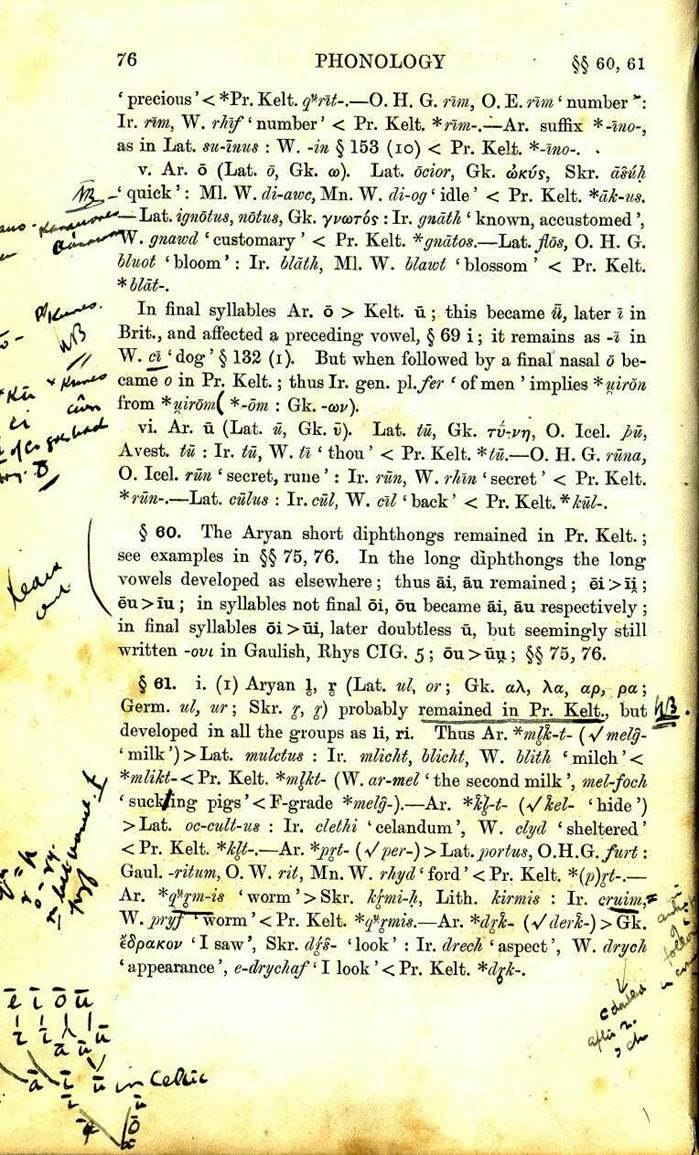

v. Ar. o (Lat. o, Gk. <o). Lat. odor, Gk. WKVS, Skr. dswS /X^-' quick':

Ml. W. di-awc, Mn. W. cli-og ' idle' < Pr. Kelt. *dk-us. ^w^—Laf. ignotus,

notus, Gk. yvwrds '• Ir. gadth' known, accustomed', ^a*^*^^- gnawd '

customary ' < Pr. Kelt. *gndtos.—Lat. flos, 0. H. G. llmt ' bloom': Ir.

Math, Ml. W. Uawt ' blossom ' < Pr. Kelt. *bldt:

rf,^--*^' In final syllables Ar. 6 > Kelt. u ; this became u, later z in A

Brit., and affected @. preceding vowel, § 69 i; it remains as -z in y/ W. cz

' dog' § 133 (i). But when followed by a final nasal o be-

v y^-"" came o in Pr. Kelt.; thus Ir. gen. pl._/er (of men '

implies *umit ^»» from *uir6m\ *-om : Gk. -air). (y^" vi. Ar. u (Lat. u,

Gk. ii). Lat. tu, Gk. TV-VIJ, 0. Icel. pw,

A vest. tu : Ir. i'a, W. tz ' thou' < Pr. Kelt. *tu.—0. H. G. w»a, 0.

Icel. y%% ' secret, rune': Ir. run, W. rhm ' secret' < Pr. Kelt. -Lat.

culiiiS : Ir. cul, W. czl' back' < Pr. Kelt. *kul-.

JL t

§ 60. The Aryan short diphthongs remained in Pr. Kelt.;

see examples in §§ 75, 76. In the long- diphthongs the long vowels developed

as elsewhere; thus ai, au remained ; ei>u;

eu > m; in syllables not final oi, ou became ai, au respectively ;

in final syllables oi>ui, later doubtless u, but seemingly still '^written

-ovi in Gaulish, Bihys CIG. 5 ; ou>uu; §§ 75, 76. ;

§ 61. i. (i) Aryan 1, r (Lat. ul, or; Gk. a\, \a, ap, pa; ;

Germ. ul, ur;

Skr. r, r) probably remained m Pr^ Kelt., but yjj^' developed in all the

groups as li, ri. Thus Ar. *mlk-t- (V meig-' milk')> Lat. mulctus : Ir,

mlicht, blicht, W. blith ' milch'< ' \(/ *mlikt-< Pr. Kelt. *mlkt- (W.

ar-mel' the second milk', mel-foch •u' ' suckpng pigs' < F-grade

*melg-).—Ar. *^-f- (Vkel- 'hide') >Lat. oc-cult-us : Ir. clethi

'celandum', W. clyd 'sheltered' <Pr. Kelt. *klt——Kv. *j,wt- {V'

per-)>~La,\,.fortus, O.R.G furt:

Gaul. -ritum, 6. W. rit, Mn. W. rhyd' ford' < Pr. Kelt. *(p)rt——

Ar. *^mi-is ' worm ' > Skr. Iwnii-Jt., Lith. kirmis : Ir. wuim,f. <^|

"W. m"ui' ' worm ' <" Pr. Kelt- ^nf-rmis—Ai\ *^'r?'_ I

A/r1/>vf'.\ •~» f~i}r 0' ^1

0 U.

l^J. ^^

'•A.VL \

W. p-yf \ worm' < Pr. Kelt. *q!'rmis.—Ar. *-dri- {*/ cleric-} >Gk.

'eSpaKov '1 saw', Skr. dfs- 'look' : Ir. drecfi 'aspect', W. drycJi

'appearance', e-drychaf''1 look'<Pr. Kelt. *drk-. i

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd

1607) (tudalen 77)

|

$$

SGANIAD AMRWD: TESTUN HEB EI GYWIRO ETO

ESCANEJAT SENSE CORREGIR

RAW SCAN: TEXT NOT YET CORRECTED

77

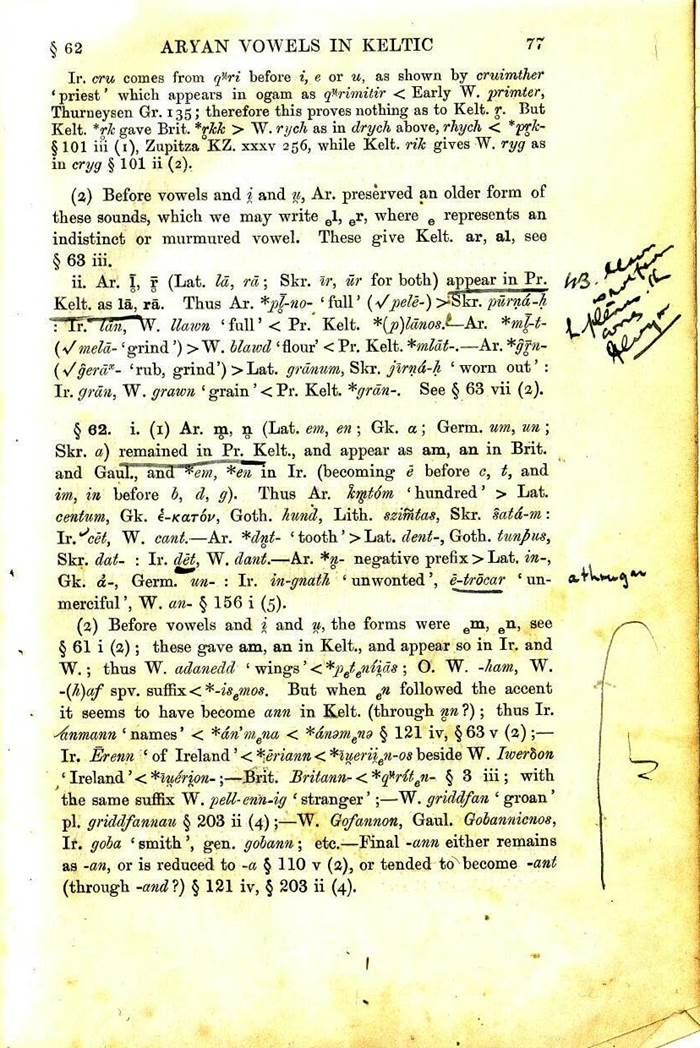

I \hc

Ir. cru conies from q^ri before i, e or u, as shown by wuimther ' priest'

which appears in ogam as qVrimitir < Early W. primter, Thurneysen Gr. 135;

therefore this proves nothing as to Kelt. r. But Kelt. *rk gave Brit. *rkk

> W. rych as in drych above, rhyoh < *prk-§ 101 iii (i), Zapitza K-Z.

xxxv 2g6, while Kelt. rik gives W. ryg as in cryg § 101 ii (2).

(a) Before vowels and i and u, Ar. preserved an older form of these sounds,

which we may write gl, gp, where g represents an indistinct or murmured

vowel. These give Kelt. ar, al, see

§63"i. Lt^ ii. Ar. 1, r (Lat. la, m; Skr. ir, ur for both) appear in Pr. /^g, 'f^'

Kelt. as la, ra. Thus Ar. *_pl-no- 'full' (Vpele-)

>"Skr"^3"I '^^/^ ' TT?:" Un~\f. llawn ' full'<

Pr.'Kelt. *{_p)ldnos.^-Ax. *mU- \)^^y\/ (•/meld- 'grind') >W. Uawd 'flour' < Pr. Kelt. *mldt-.—Ar. *gn-

"-' "- ^f/ (•/gei'o"- 'rub, grind')> Lat. grdnum, Skr.

jwnd-h 'worn out' :

Ir. gran, W. gmwn ' grain' < Pr. Kelt. *gran-. See § 63 vii (a).

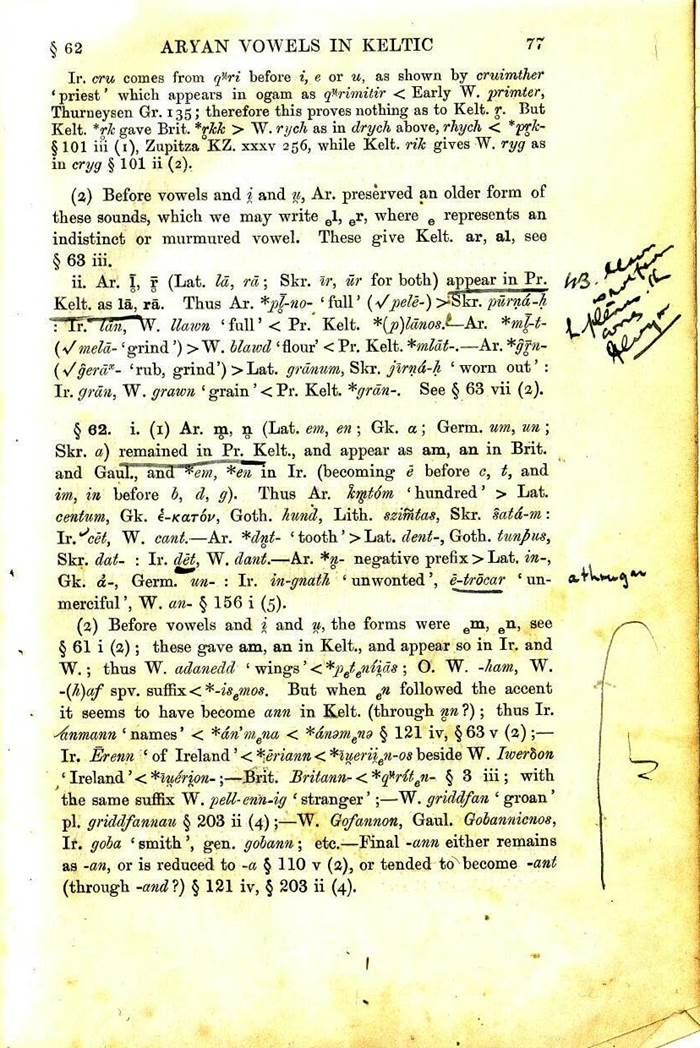

§ 62. i. (i) Ar. m, n. (Lat. em, en; Gk. .a; Germ. urn, un;

Skr. a) remained in Pr. Kelt., and appear as am, an in. Brit.

e'xssw-wswy ^ysaas^^'^f^u; . <'

and Gaul., and^w/?, ^en in Ir. (becoming e before c, t, and im, in before 6,

d, g). Thus Ar. K^itdm ' hundred' > Lat. centum, Gk. f.-Ka.rw, Goth. Aund,

Lith. szimtas, Skr. satd-m:

Ir. cet, W. cant.—Ar. *dnt- 'tooth' > Lat. dent-, Goth. tunpus, Skr. dat-